authors

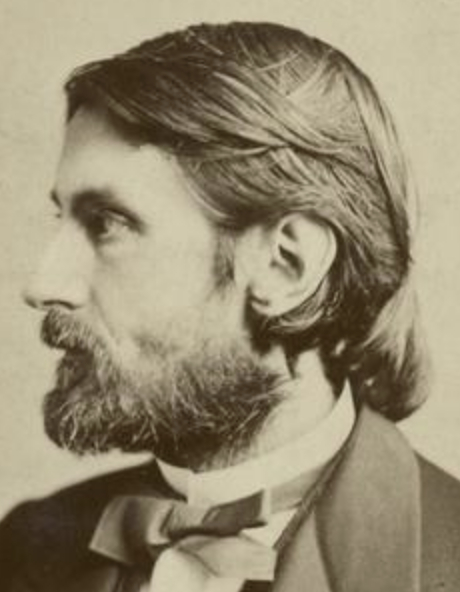

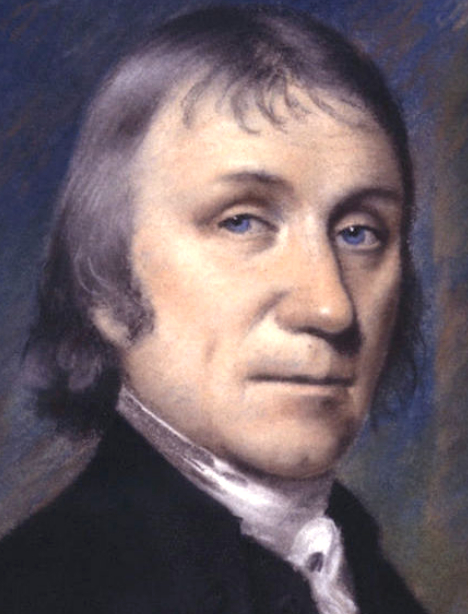

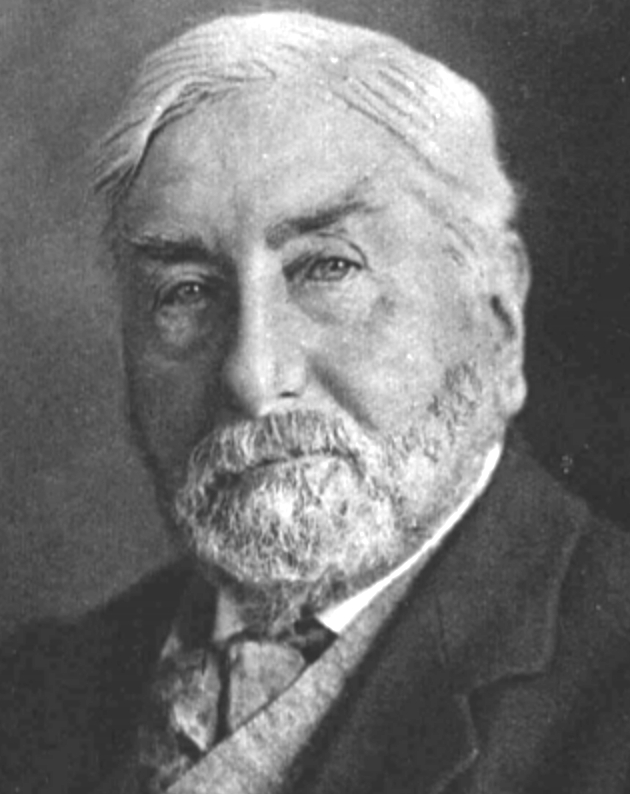

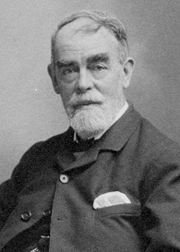

Gustave Tridon

On this date in 1841, Edme Marie Gustave Tridon was born into a wealthy family in Châtillon-sur-Seine, France. He studied law and was qualified to practice it but never did. As a student he became a radical republican socialist and opponent of Emperor Napoleon III.

He also embraced metaphysical materialism and atheism, considering the latter the highest achievement of scientific reason. Among the figures of the French Revolution, he most admired Jacques-René Hébert, a Parisian guillotined by the Jacobins. Tridon published two books on the Hébertists: The Hébertists: Protest Against a Historical Calumny (1864) and The Commune of 1793: The Hébertists (1871). He also published a history titled The Gironde and the Girondists (1869).

Tridon’s views corresponded with those of veteran revolutionary Louis Auguste Blanqui, whom he met in the Sainte-Pélagie prison in 1865. Tridon had been incarcerated there for writing anti-religious articles deemed contrary to morality. After his release he founded the journal Candide, which was eventually shut down by the authorities, and Tridon was jailed again.

In 1866 he joined the First International, one of the first Blanquists to do so. On his return to France from the International congress, he was again arrested and remained in prison until 1868. He founded the journal Revue and contributed articles to several other journals. In January 1870, fearing arrest, he fled to Brussels. He was sentenced in absentia to deportation.

A dark stain on his legacy was the so-called racial anti-Semitism in vogue within the French anarchist left during the mid-19th century. Tridon wrote Du Molochisme Juif, a screed published posthumously that pleaded for an Aryan victory over the Jews to save Western civilization and referred to Jews as “a carnivorous race sacrificing humans to its gods.” (Judd L. Teller, Scapegoat of Revolution, 1954)

The exact cause of his death at age 30 is uncertain. Some sources say it was suicide, but British author Joseph Mazzini Wheeler wrote that while imprisoned in Sainte-Pélagie, he “contracted the malady which killed him.”

Historian Maurice Dommanget wrote in Hommes et Choses de la Commune (Men and Things of the Commune) that “This twenty-nine-year-old man is already worn out. He is hunched to the point that he looks like he is hunchbacked, his face is riddled with pimples, his cheeks hang down. His weak constitution, his delicate health did not allow him to overcome the feverish militant life and the long stays in prison.” (D. 1871)

“He received the most splendid Freethinker’s funeral witnessed in Belgium.”

— "A Biographical Dictionary of Freethinkers of All Ages and Nations," by Joseph Mazzini Wheeler (1889)

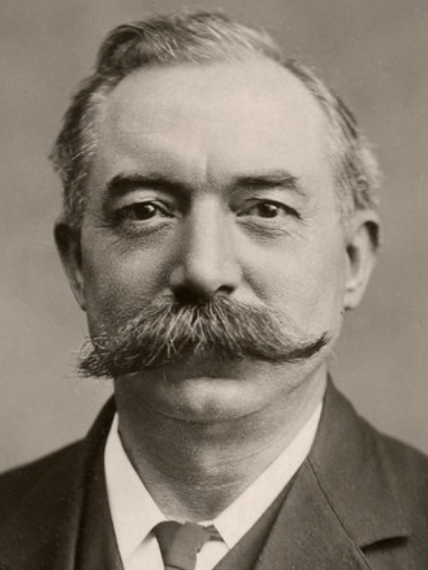

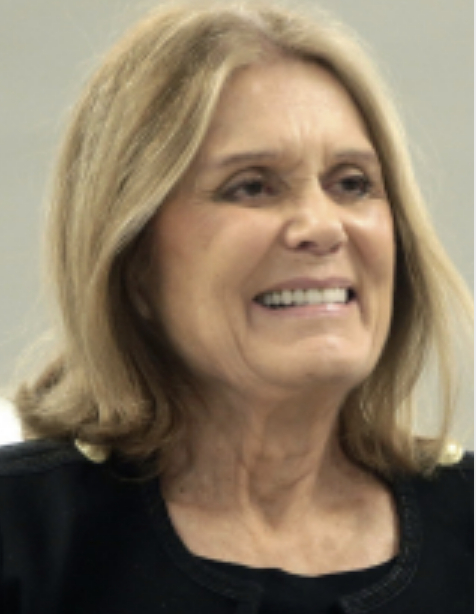

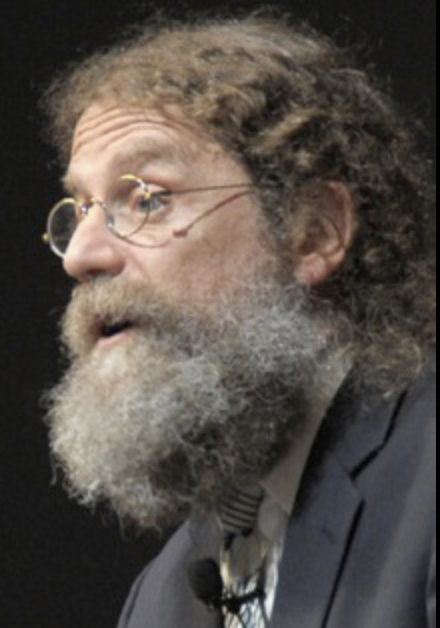

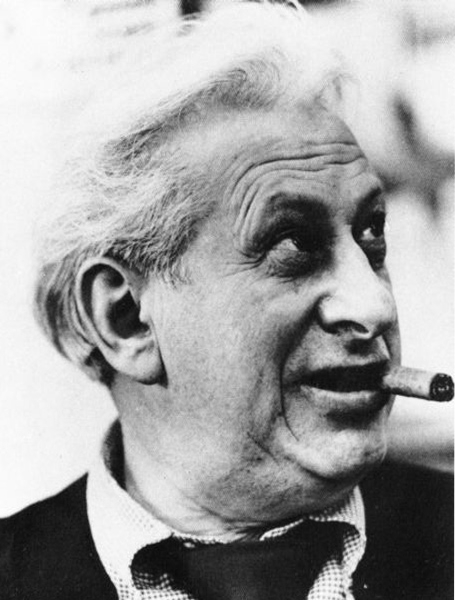

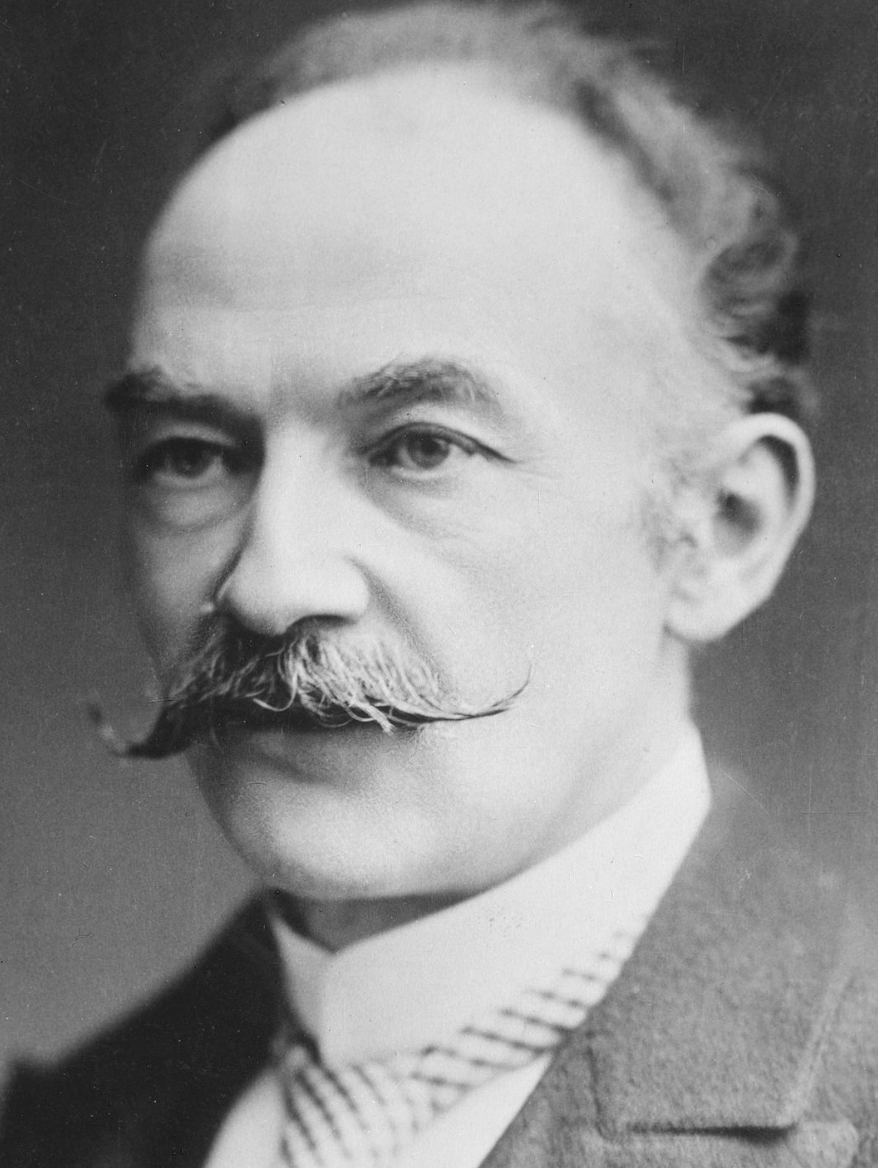

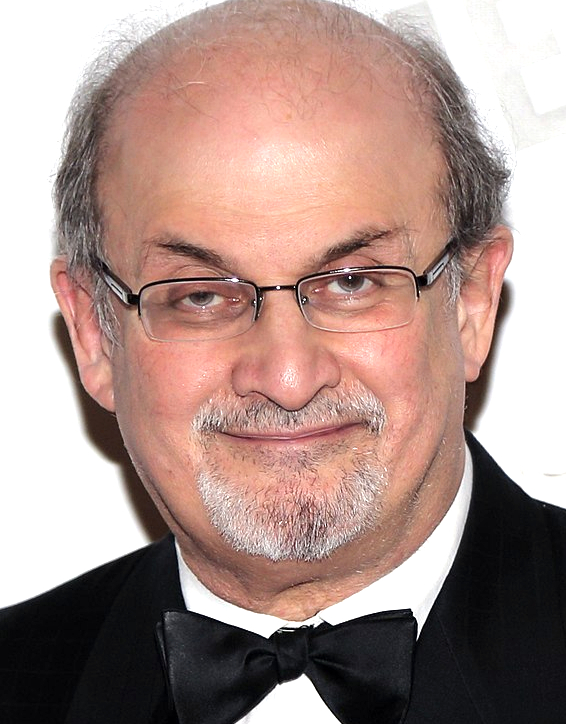

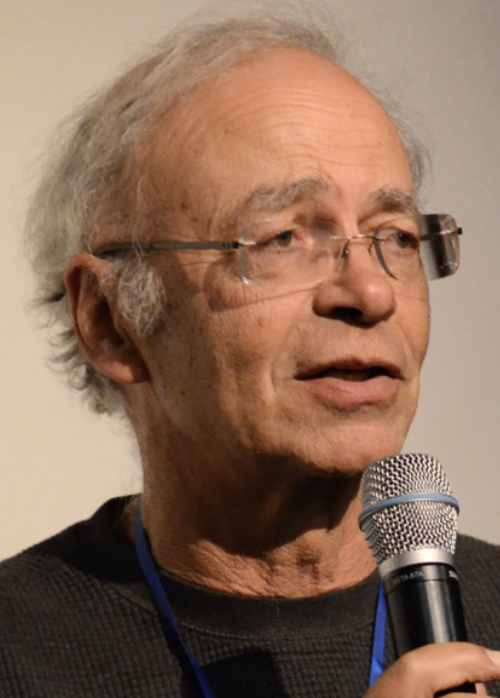

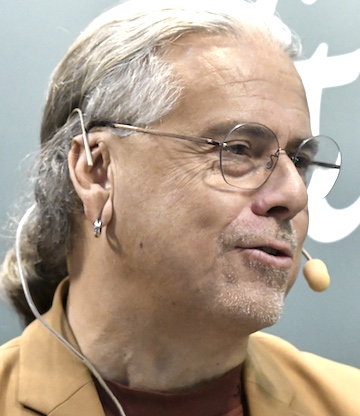

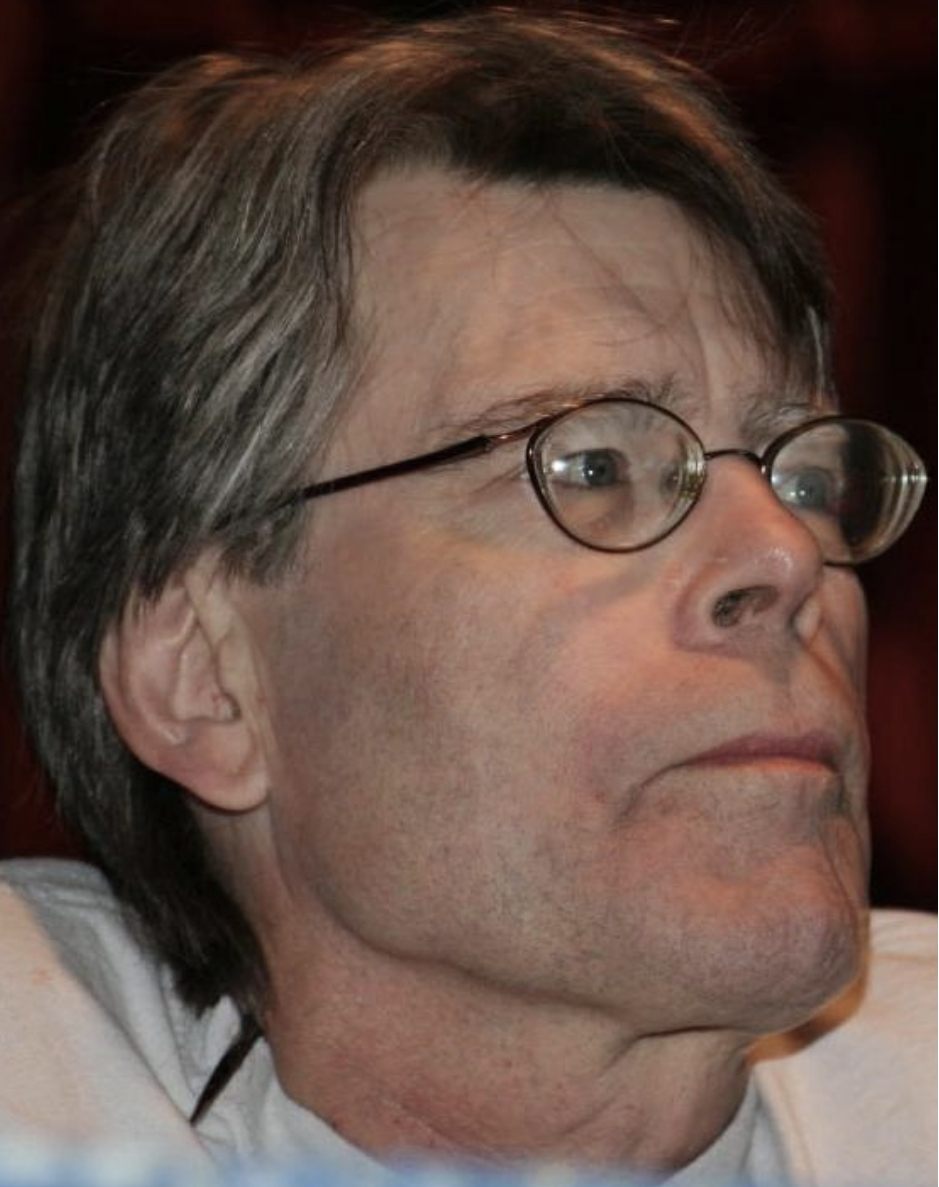

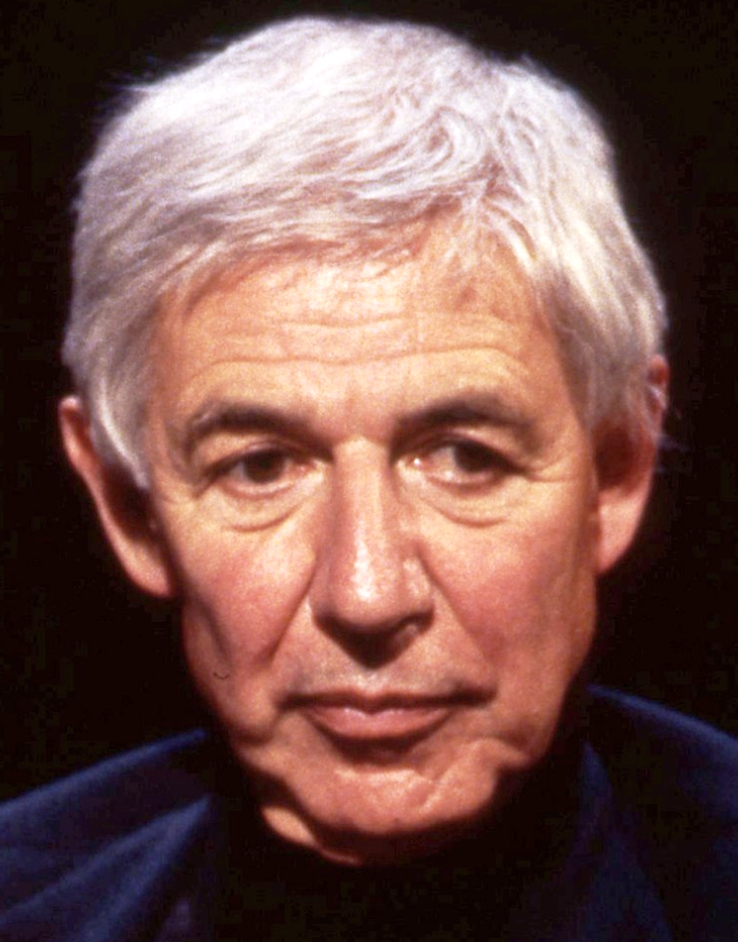

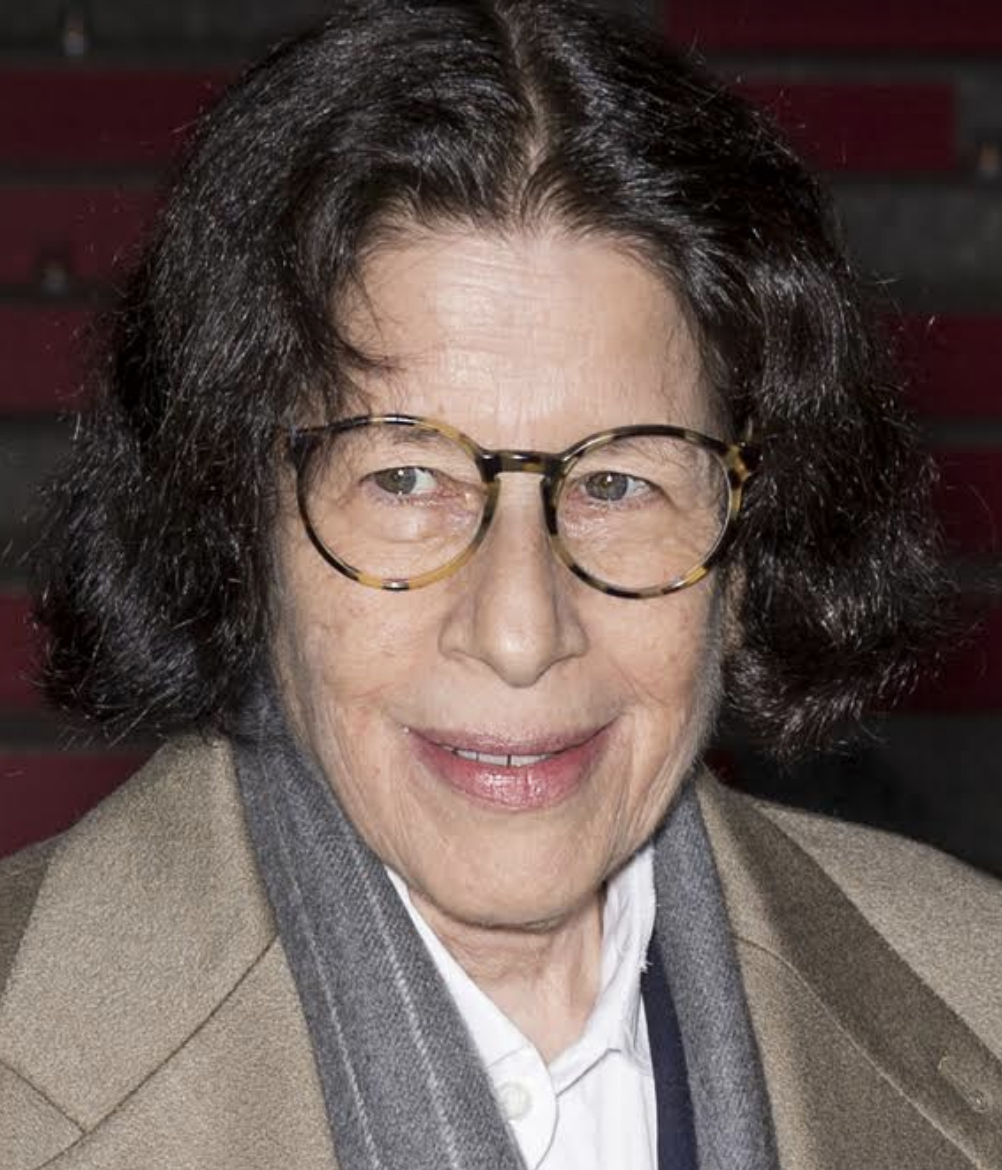

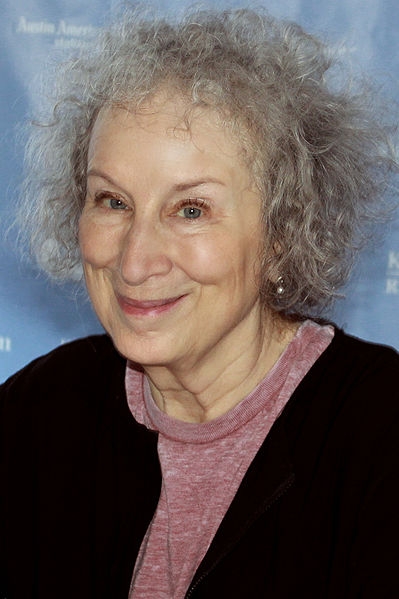

Michel Onfray

On this date in 1959, Michel Onfray was born in Argentan in northwest France. He taught philosophy in high school in Caen from 1983 to 2002. During this time he received his doctorate from the University of Caen in 1986. Onfray’s first book, Le ventre des philosophes, critique de la raison diététique (The Philosophers’ Stomach: A Critique of Dietary Reasoning) was published in 1989.

Onfray has written over 100 published books, which are popular throughout France as well as other parts of Europe, Latin America and even East Asia. However, only one, Traité d’Atheologie (2005) has been published in English: Atheist Manifesto: The Case Against Christianity, Judaism, and Islam.

In 2002 he founded the Université Populaire (People’s University) in Caen, at which he and others give free lectures on philosophy and other intellectual topics. The main thrust of Onfray’s work is atheist, materialist and hedonist. On the Brain@McGill website affiliated with the Institute of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addiction, Bruno Dubuc writes: “The French author Michel Onfray may be the philosopher who best represents the hedonist tradition today. In his many works, Onfray attempts to reposition the human body at the centre of our world view. … Onfray specializes in a certain ancient philosophy that has been buried under 2000 years of Christianity.”

In Atheist Manifesto, Onfray makes a strong case for removing all the remnants of Judeo-Christian ideology from our secular culture. Onfray is also a historian of philosophy who loves to point out why many philosophers are undeserving of our respect. He has so far published six volumes in the series La contre histoire de la philosophie (The Counter-History of Philosophy).

PHOTO of Onfray by Perline via CC 3.0,

“I persist in preferring philosophers to rabbis, priests, imams, ayatollahs, and mullahs. Rather than trust their theological hocus-pocus, I prefer to draw on alternatives to the dominant philosophical historiography: the laughers, materialists, radicals, cynics, hedonists, atheists, sensualists, voluptuaries. They know that there is only one world, and that promotion of an afterlife deprives us of the enjoyment and benefit of the only one there is. A genuinely deadly sin.”

— Onfray, "Atheist Manifesto" (2005)

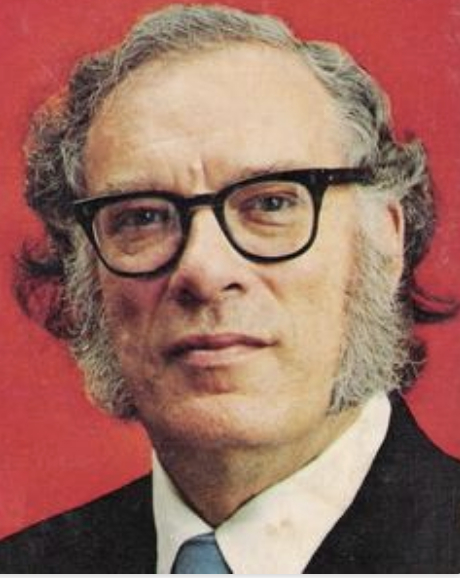

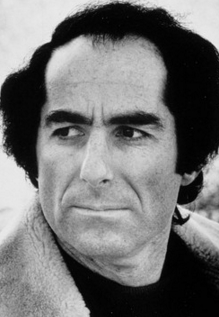

Isaac Asimov

On this day in 1920, Isaac Asimov, a self-described “second-generation freethinker” and one of the world’s most prolific authors, was born in Petrovichi, Russia. He moved with his family to Brooklyn, New York, in 1923 and became a naturalized citizen in 1928. He sold one of his earliest published short stories, “Nightfall,” in 1941, which was eventually voted the best science-fiction short story ever written, by the Science Fiction Writers of America.

Asimov graduated from Columbia University in 1939, earned his M.A. in 1941 and a Ph.D. in chemistry in 1948. He was hired by Boston University’s School of Medicine to teach biochemistry the following year. He became an associate professor of biochemistry in 1955 and professor in 1979, although he stopped teaching in 1958 to devote his life to writing.

I, Robot (1950) was the title of his first collection of short stories. Employing the “Asimovian Law of Composition,” which meant writing from nine to five, seven days a week (often closer to 6:30 a.m. to 10 p.m.), he averaged at least 12 new books a year. Asimov won five Hugos, three Nebula Awards, and his best-known “Foundation” trilogy was given a 1966 Hugo as “Best All-Time Science-Fiction Series.” Nonfiction works by Asimov were typically encyclopedic in range, such as his well-known Asimov’s Guide to the Bible (1968) and Asimov’s Annotated Paradise Lost (1974). He wrote a series of popular books on science and history, and even a guide to Shakespeare.

Asimov was an atheist: “I am Jewish in the sense that if an Arab wanted to throw a rock at a Jew, I would qualify as a target as far as he was concerned. However, I do not practice Judaism or any other religion.” (March 17, 1969 letter.) “Properly read, the Bible is the most potent force for atheism ever conceived.” (Feb. 22, 1966 letter.) He published 470 books, covering every category in the Dewey Decimal System, fiction and nonfiction.

Asimov was married twice and had a son and daughter from his first marriage. His death at age 72 from heart and kidney failure was a consequence of AIDS, a fact later revealed by his wife Janet Asimov. (D. 1992)

“Just the force of rational argument in the end cannot be withstood.”

— Asimov, solstice speech to the New Jersey Freedom From Religion Foundation (Dec. 22, 1985)

Zora Neale Hurston

On this date in 1891, writer and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston was born in Eatonville, Fla., the first all-black community to be incorporated in the U.S. Her mother was a country schoolteacher and her father a Baptist preacher who became three-term mayor of Eatonville. “My head was full of misty fumes of doubt,” she would later write. “Neither could I understand the passionate declarations of love for a being that nobody could see. Your family, your puppy and the new bull-calf, yes. But a spirit away off who found fault with everybody all the time, that was more than I could fathom.”

She was farmed out to relatives when her mother died in 1904. By 14 she had left town to work as a maid for whites. As a live-in maid she enrolled at Morgan Academy in Baltimore. She attended Howard University intermittently from 1918-24 while working as a manicurist and maid for prominent blacks. She moved to New York City in 1925 with “$1.50, no job, no friends, and a lot of hope,” into the midst of the Harlem Renaissance.

Her short story “Spunk” (1925) brought her notice. Fannie Hurst, author of Imitation of Life (1933), gave her a job. Another white patroness arranged a scholarship for her at Barnard College. Hurston graduated in 1928 and did graduate study at Columbia, where her talents caught the eye of an anthropology professor, who suggested she incorporate anthropology into her writing.

A commission by a wealthy white patron to collect folklore stymied her career, since the contract barred Hurston from writing. In 1933 she wrote her best-known story, “The Gilded Six-Bits.” Her first novel, Jonah’s Gourd Vine, debuted in 1934, followed by Mules and Men (1937), Tell My Horse (1937) and the classic novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937). In all she wrote seven books plus her memoir Dust Tracks on a Road (1942).

Many of her short stories were published in magazines and anthologies. Hurston married three times but none of the marriages lasted. She was forced to take diverse “day jobs” to support her writing, from working as a drama instructor at North Carolina College for Negroes at Durham (1939), to working as a maid once again in 1950.

Writer Alice Walker revived interest in Hurston in the 1970s. A Hurston reader, I Love Myself When I am Laughing … and Then Again When I am Looking Mean and Impressive, was published in 1979. She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1994. The Complete Stories came out in 1995.

She died of a stroke and heart disease at age 69 in a home for the poor and was buried in an unmarked grave in Fort Pierce, Fla. (D. 1960)

“Prayer seems to me a cry of weakness, and an attempt to avoid, by trickery, the rules of the game as laid down. I do not choose to admit weakness. I accept the challenge of responsibility. Life, as it is, does not frighten me, since I have made my peace with the universe as I find it, and bow to its laws.”

— Hurston in her autobiography "Dust Tracks on a Road" (1942)

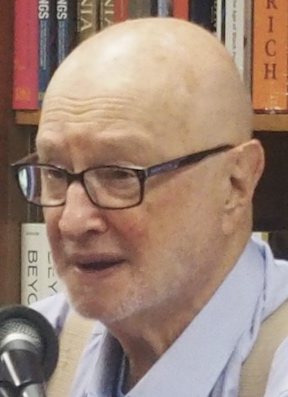

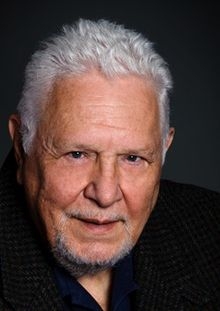

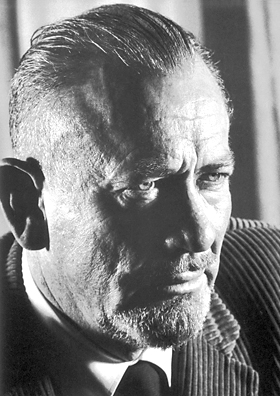

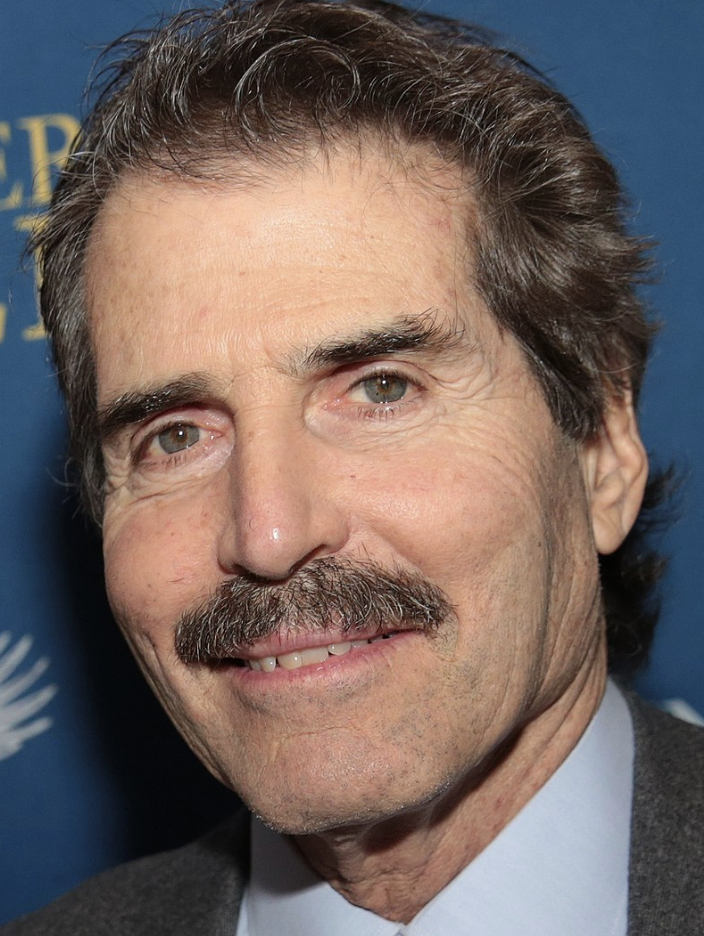

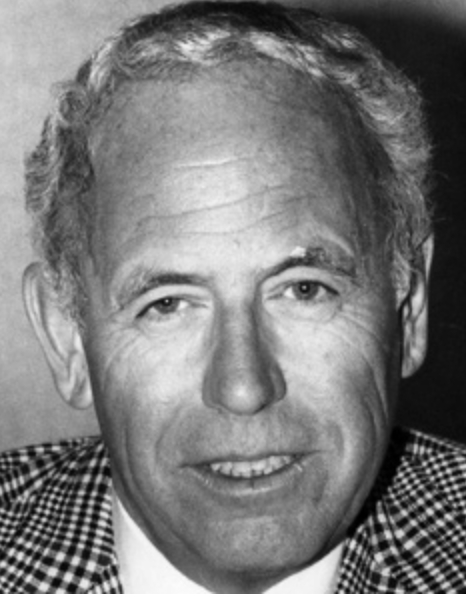

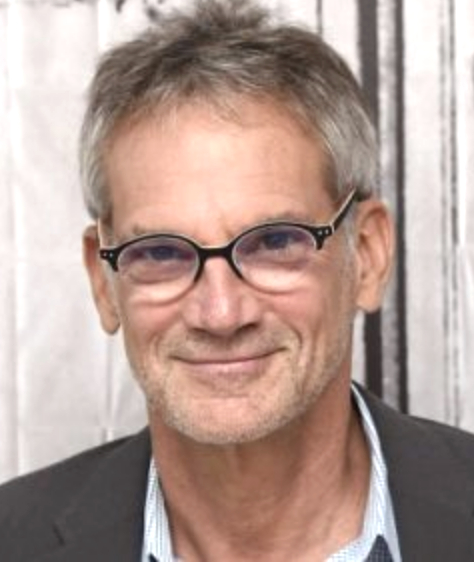

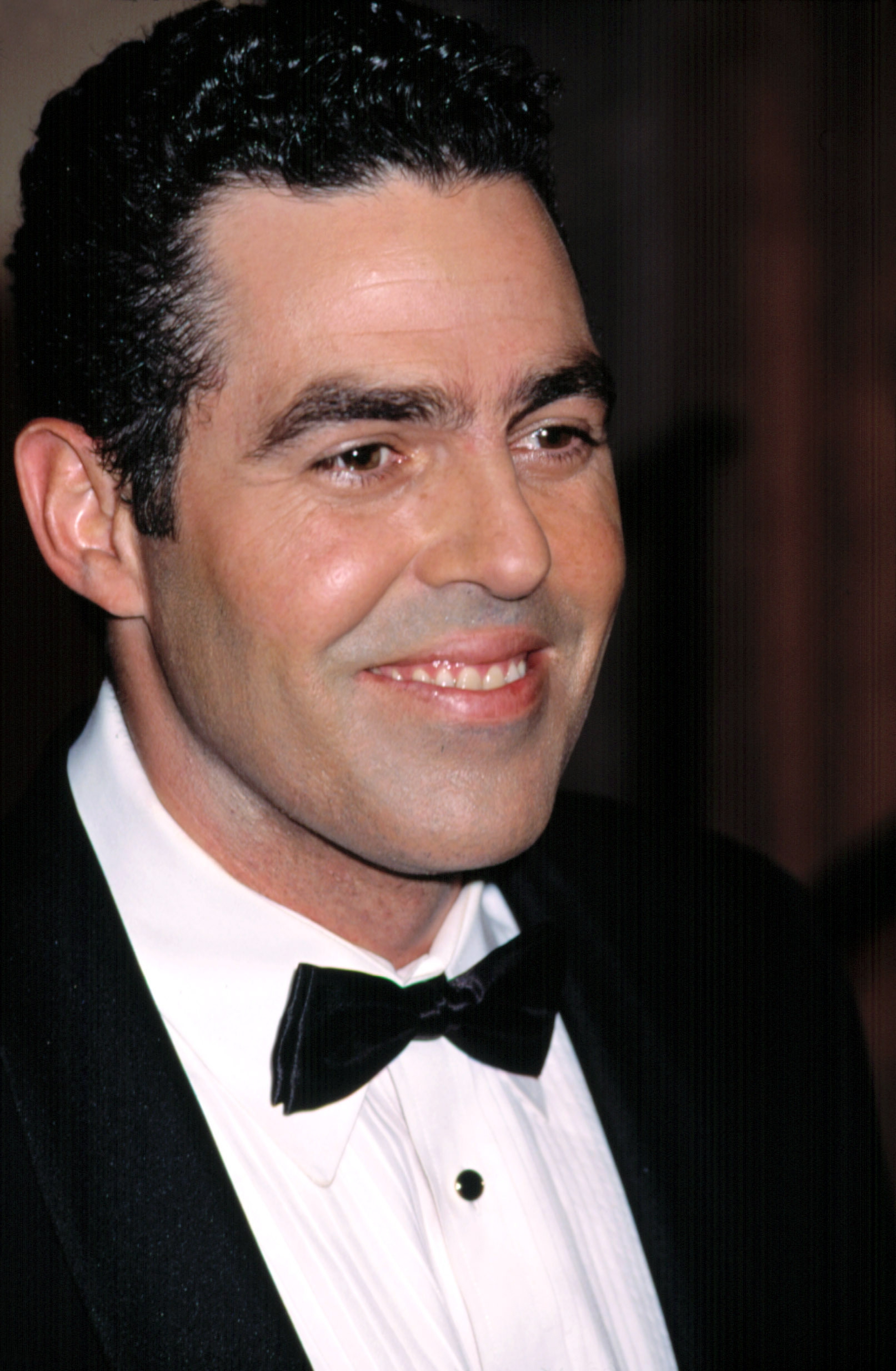

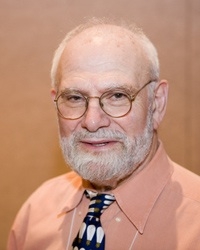

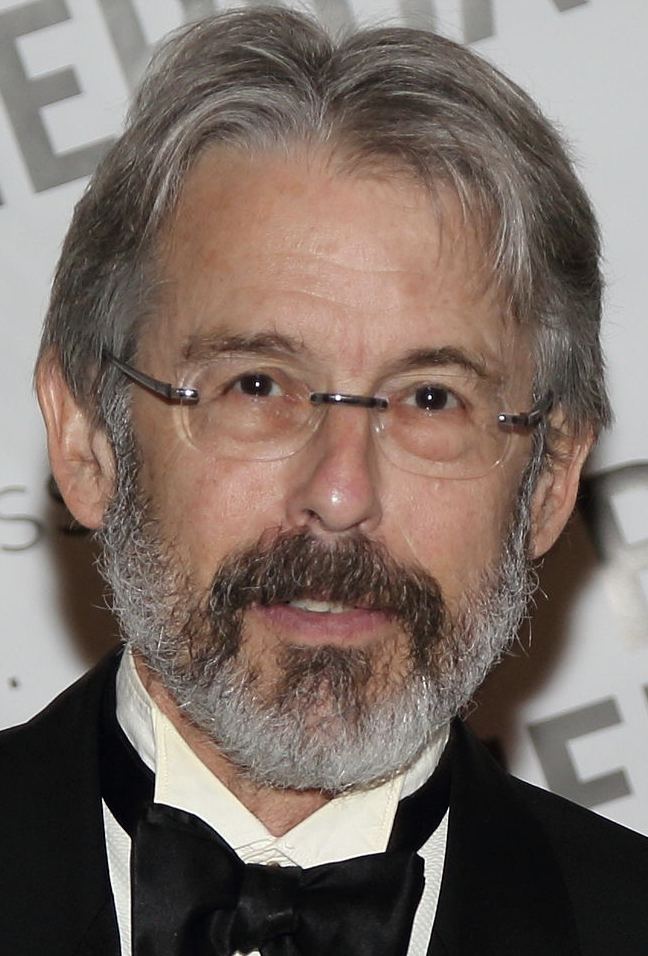

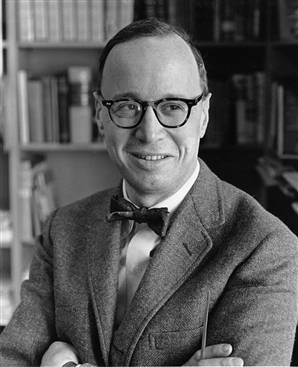

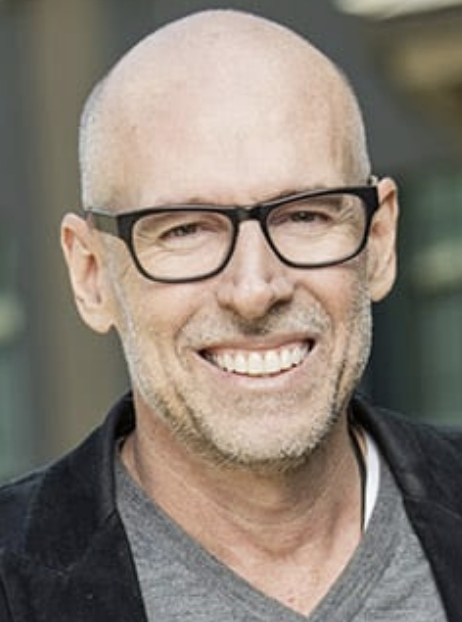

Lewis Lapham

On this date in 1935, Lewis Henry Lapham was born in San Francisco. He earned his bachelor’s degree in history from Yale University in 1956 and attended Cambridge University (1956–57). After graduation he worked as a reporter for the San Francisco Examiner (1957-60) and at age 25 became the U.N. correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune (1960-62). He later became managing editor of the prominent literary journal Harper’s Magazine (1971-75) and was soon appointed its editor (1976-2006).

He was a prolific journalist who wrote articles for many publications, including The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. In 2007, Lapham founded and became editor of Lapham’s Quarterly, a history magazine. His many books included Waiting for the Barbarians (1998) and Gag Rule: On the Suppression of Dissent and the Stifling of Democracy (2005).

Lapham was also the host of the television show “Bookmark” (1988-91). He received the 1994 and 1995 National Magazine Awards for his journalistic contributions to Harper’s. In 2007, Lapham was included in the American Society of Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame. He married Joan Brooke Reaves in 1972 and they had three children: Anthony, Elizabeth and Winston. Andrew married the daughter of former Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney.

“As an unbaptized child raised in a family unaffiliated with the teachings of a church, I missed the explanation as to why the stories about Moses and Jesus were to be taken as true while those about Apollo and Rumpelstiltskin were not,” Lapham wrote of his lifelong nonbelief in “Mandates of Heaven,” the introduction to the Winter 2010 issue of Laphams Quarterly.

He continued: “[French philosopher Michel] Onfray observes that ‘a fiction does not die, an illusion never passes away,’ situating Yahwey, together with Ulysses, Allah, Lancelot of the Lake, and Gitche Manitou, among the immortals sustained on the life-support systems of poetry and the high approval ratings awarded to magicians pulling rabbits out of hats.”

He expressed his disdain for the intersection of church and state in America, saying, “The dominant trait in the national character is the longing for transcendence and the belief in what isn’t there — the promise of the sweet hereafter that sells subprime mortgages in Florida and corporate skyboxes in heaven.” He died in Rome at age 89. (D. 2024)

PHOTO: By Terry Ballard under CC 2.0.

“God is the greatest of man’s inventions, and we are an inventive people, shaping the tools that in turn shape us, and we have at hand the technology to tell a new story congruent with the picture of the earth as seen from space instead of the one drawn on the maps available to the prophets wandering the roads of the early Roman Empire.”

— Lewis Lapham, Lapham's Quarterly (Winter 2010)

Simone de Beauvoir

On this date in 1908, French author and atheist Simone de Beauvoir was born in Paris to Georges Bertrand de Beauvoir, a legal secretary, and Françoise de Beauvoir (née Brasseur), a wealthy banker’s daughter and devout Catholic. A deeply religious child, she initially wanted to be a nun but at age 14 had a crisis of faith and concluded there was no God. She instead studied and taught philosophy and wrote prolifically.

Educated at the Sorbonne, de Beauvoir played a major role in the French Existentialist movement, along with close companion and atheist Jean-Paul Sartre. She is best-known for her monumental work The Second Sex (1949), in which she posited that society treats woman as “the other.” She also wrote popular novels and other nonfiction such as A Very Easy Death (1964). De Beauvoir championed freedom as the ultimate good.

She and Sartre were involved romantically from 1929 until his death in 1980. She never married or had children while engaging in a number of open relationships, including with women. Perhaps her most famous lover was American author Nelson Algren, whom she met in Chicago in 1947. She died of pneumonia at age 78 and is buried next to Sartre in Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris. (D. 1986)

PHOTO: Moshe Milner photo, Creative Commons 3.0

“Man enjoys the great advantage of having a God endorse the codes he writes; and since man exercises a sovereign authority over woman, it is especially fortunate that this authority has been vested in him by the Supreme Being. For the Jews, Mohammedans, and the Christians, among others, man is master by divine right; the fear of God, therefore, will repress any impulse toward revolt in the downtrodden female.”

— Simone de Beauvoir, "The Second Sex" (1949, translated and edited by H.M. Parshley, 1953)

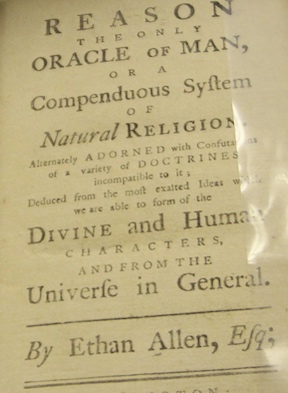

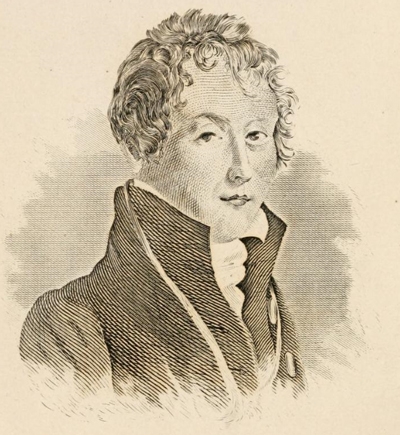

Ethan Allen

On this date in 1738, Ethan Allen was born in Litchfield, Conn., the eldest of eight children. Allen was the author of the first rationalist book published in America, titled Reason, the Only Oracle of Man: Or, a Compendious System of Natural Religion (1784). The New England Revolutionary War soldier critiqued Calvinist theology while promoting a deistic philosophy.

He married Mary Brownson, five years his senior, in 1762. They had a daughter, Loraine, the next year and bought a small farm which they developed into an ironworks. The marriage was unhappy as Mary was rigidly religious and barely literate. They had four more children; only two survived to adulthood. In 1770 Allen was named colonel of the “Green Mountain Boys” in Vermont and after the Revolutionary War became a member of the Vermont Legislature. Before the war he formed a land-speculation company with three of his brothers.

Reason, the Only Oracle of Man was a typical Allen polemic but its target was religious, not political. Specifically targeting Christianity, it attacked the bible, established churches and the priesthood. In it he wrote, “In those parts of the world where learning and science have prevailed, miracles have ceased; but in those parts of it as are barbarous and ignorant, miracles are still in vogue.” Allen espoused a mixture of deism, Spinoza‘s naturalist views and precursors of transcendentalism, with man acting as a free agent within the natural world.

Mary Allen died in 1783 of consumption, followed several months later by Loraine’s death. In 1784 he married Frances “Fanny” Montresor Brush Buchanan, a widow. They had three children, the last a son born several months after Allen’s death at age 51 of what was thought to be a cerebral hemorrhage. His two sons went on to graduate from West Point. (D. 1789)

“In the circle of my acquaintance, (which has not been small), I have generally been denominated a Deist, the reality of which I never disputed, being conscious I am no Christian, except mere infant baptism make me one; and as to being a Deist, I know not, strictly speaking, whether I am one or not, for I have never read their writings …”

— Allen, "Reason, the Only Oracle of Man" (1784)

Molière

On this date in 1622, playwright and poet Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, who adopted the stage name Molière as an actor, was born in Paris. His father was an upholsterer/valet to King Louis XIII. Molière studied philosophy in college, started a Parisian acting troupe and toured the provinces with it for many years, acting, directing and writing.

As a favorite of King Louis XIV, he produced a succession of 12 popular comedies still being performed, including “The School for Wives” (1662), “Don Juan” (1665), “Le Misanthrope” (1666) and “Tartuffe” (1667), all irreverent and increasingly irreligious. “Tartuffe,” a satire on religiosity, originally featured a hypocritical priest. Although Molière rewrote Tartuffe’s profession to avoid scandal, some religious officials nevertheless called for him to be burned alive as punishment for his impiety. He would claim he was attacking hypocrisy more than religion.

He married actress Armande Bejart when she was 19 and they had a daughter, Esprit-Madeleine, in 1665. Becoming ill while playing the lead in his play “Le Malade imaginaire” (“The Imaginary Invalid”), Molière insisted on finishing the show, after which he died. He had long suffered from tuberculosis. The church refused to bury him in sanctified ground because he had not received the last rites and did not renounce his profession as an actor before his death. When the king intervened, the archbishop of Paris allowed him to be buried only after sunset among the suicides’ and paupers’ graves with no requiem Masses permitted in the church. (D. 1673)

“Though living in an age of reason, he had the good sense not to proselytize but rather to animate the absurd …”

— Encyclopedia Britannica entry on Molière

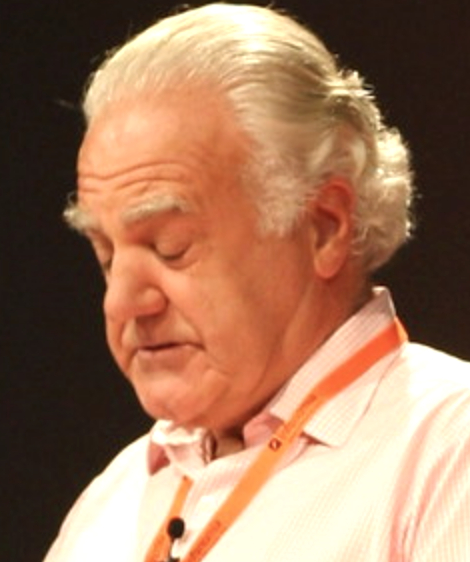

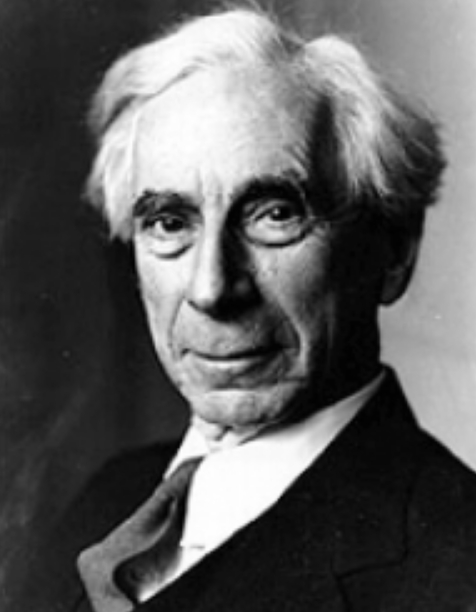

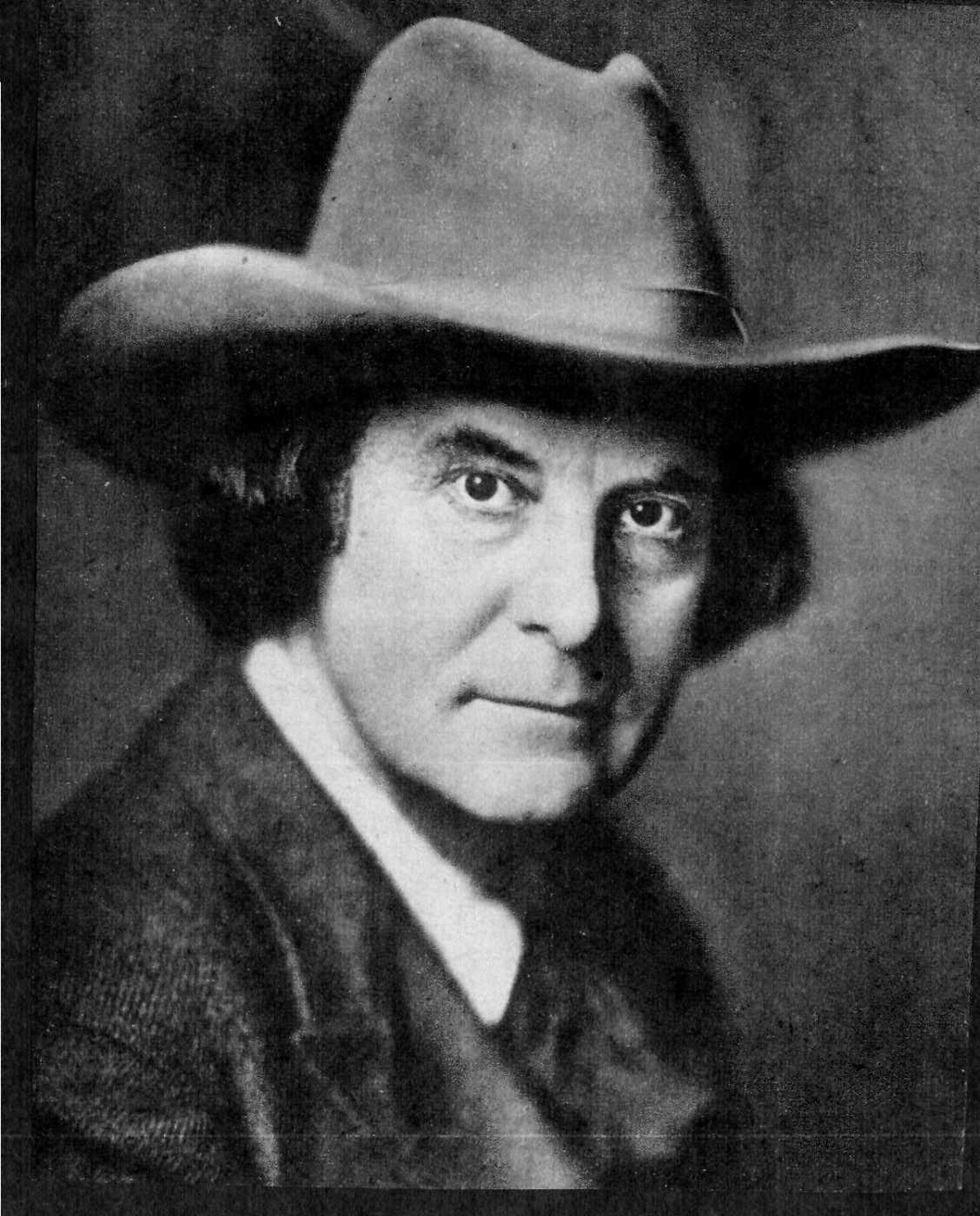

A.A. Milne

On this date in 1882, classic children’s author Alan Alexander Milne, known as A.A. Milne, was born in England and brought up in London. With his brothers he attended his schoolteacher father’s school, Henley House. One of his influential teachers there was H.G. Wells. Attending Cambridge on a mathematics scholarship, Milne was given the gift of 1,000 pounds by his father upon graduation. He used it to move back to London and become a writer.

Milne freelanced for newspapers, joined the staff of Punch magazine and wrote a book that flopped, Lovers in London. In 1913 he married Dorothy “Daphne” de Sélincourt. In 1915 he volunteered in World War I and wrote his first play while serving. His only child, Christopher Robin, was born in 1920. In his 1974 book The Enchanted Places, Christopher wrote about being estranged from his parents and resenting what he came to see as his father’s exploitation of his childhood.

In his obituary in 1996, The Observer wrote: “Christopher Robin, a ‘sweet and decent’ man who overcame a childhood in which he was haunted by Pooh and taunted by peers, has left without saying his prayers – he was a dedicated atheist – aged 75.”

Milne’s When We Were Young was published in 1924, followed by Winnie the Pooh (1926), The House at Pooh Corner (1926) and Now We Are Six (1927). Milne subsequently wrote several plays, a detective novel and, in 1952, Year In, Year Out. (D. 1956)

PHOTO: Milne and Christopher Robin in 1926.

“The Old Testament is responsible for more atheism, agnosticism, disbelief — call it what you will — than any book ever written; it has emptied more churches than all the counter-attractions of cinema, motor bicycle and golf course.”

— A.A. Milne, cited in "2000 Years of Disbelief" by James A. Haught (1996)

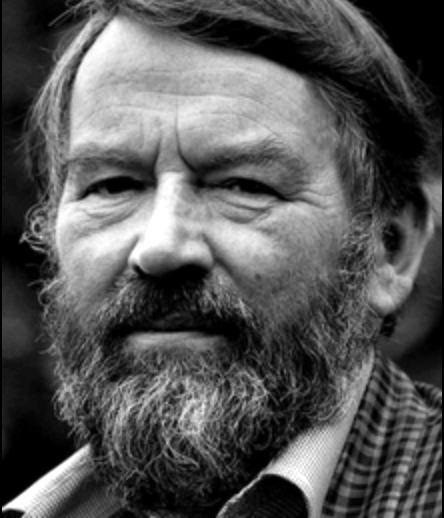

Niall Shanks

On this date in 1959, Niall Shanks was born in Cheshire, England. He earned his bachelor’s degree in philosophy from the University of Leeds in 1979, his master’s degree in philosophy from the University of Liverpool in 1981 and his Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Alberta, Canada. Shanks taught philosophy, biological sciences, physics and astronomy at East Tennessee State University (1991–2005) and at Wichita State University in Kansas (2005–11). He was especially interested in evolutionary biology and wrote several books, including Brute Science: The Dilemmas of Animal Experimentation (with Hugh LaFollette, 1997), God, the Devil, and Darwin: A Critique of Intelligent Design Theory (2004) and Animal Models in the Light of Evolution (2009).

Shanks was a self-described atheist who strongly supported evolution education. In his article “Fighting for Our Sanity in Tennessee,” published in Volume 21 of Free Inquiry magazine, he described his experience of being a nonbeliever who taught evolution in the bible belt: “I am an atheist for the same reason that I am an ‘asantaclausist.’ There is no convincing evidence to support claims about the existence of either alleged entity. Actually Santa may be the better off of the two, for the sincere testimony of small children is a tad more convincing than that of wily adults with sophistical arguments and axes to grind.”

In God, the Devil, and Darwin, Shanks denounced creation science: “The real motivations of the intelligent design movement … have little to do with science but a lot to do with politics and power — in particular, the imposition of discriminatory, conservative Christian values on our educational, legal, social and political institutions.” Shanks continued, “While we in the West readily point a finger at Islamic fundamentalism, we all too readily downplay the Christian fundamentalism in our own midst. The social and political consequences of religious fundamentalism can be enormous.”

He died in Wichita in 2011 at age 52 following a lengthy illness.

“Of God, the Devil and Darwin, we have really good scientific evidence for the existence of only Darwin.”

— Shanks, "God, the Devil, and Darwin" (2004)

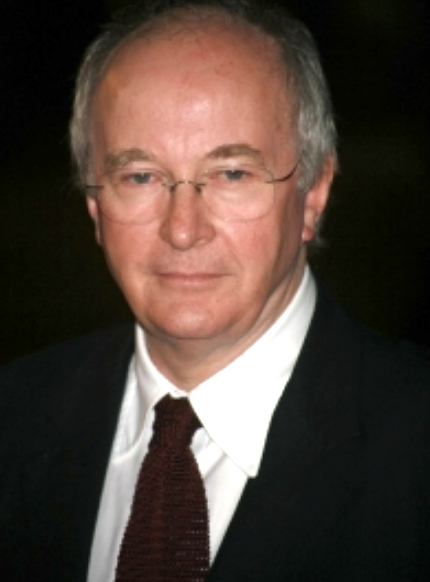

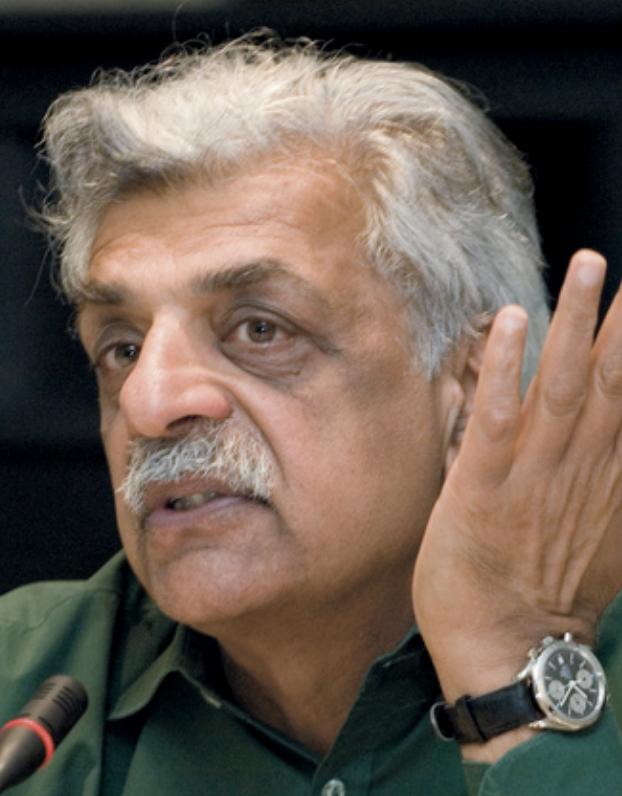

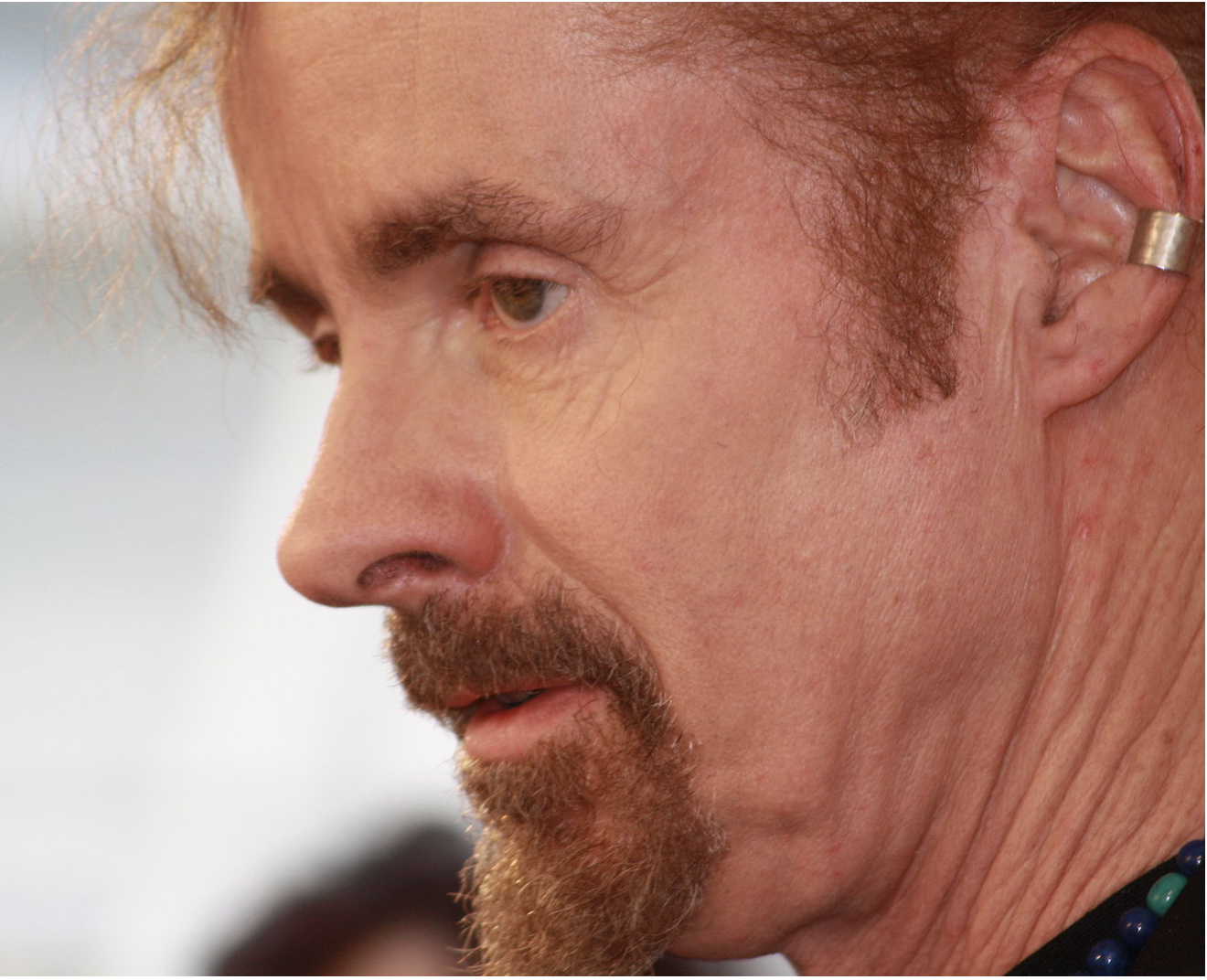

Julian Barnes

On this date in 1946, Julian Barnes was born in Leicester, England. He attended the City of London School, and graduated from Magdalen College in 1968 with a degree in modern languages. He became a reviewer and editor for the New Statesman and New Review in 1977 and worked as a television critic for the New Statesman from 1979-86. Barnes has published 18 novels (some under the pseudonym of Dan Kavanagh) as of this writing. The Sense of an Ending won the 2011 Booker Prize. The most recent are The Noise of Time (2016), The Only Story (2018) and The Man in the Red Coat (2019).

Barnes married literary agent Pat Kavanagh in 1979 and was widowed in 2011 after Kavanagh died of a brain tumor. He is the author of Nothing to be Frightened Of, a 2008 memoir focusing on death and mortality. “I don’t believe in God but I miss him,” Barnes proclaimed in the opening sentence. In a 2008 interview with Maclean’s magazine, he further explained, “I regard myself as a rationalist.”

PHOTO: Barnes in 2019. CC 4.0

“It is a bizarre thought that in this presidential cycle we could have had a woman in the White House, we might have a black man in the White House, but if either of them had said they were atheists neither of them would have had a hope in hell.”

— Barnes, interview with Maclean’s magazine (2008)

Beatrice Webb

On this date in 1858, Beatrice Webb (née Beatrice Potter) was born in Gloucestershire, England. The eighth of nine sisters, Potter’s mother resented her for not having been born a boy. Like most Victorian girls, Potter received a poor education in spite of her father’s wealthy career as a timber entrepreneur. Unusually though, her father, unlike most Victorian men, believed in the intellectual equality, if not superiority of women. As a teenager, with an increasingly inquisitive mind, Potter read every history, economy and philosophy book within reach and began to rebel against her privileged life.

Herbert Spencer, a close friend of the family, intrigued Potter with his “scientific method,” which she believed could be applied to solve society’s social problems. She was one of the first researchers to argue that poverty has underlying causes instead of being a deserved state. By 1885 her research, including on the English cooperative movement and housing projects for the poor, inspired her to break with capitalism and openly advocate socialism. The success of her research was her fearless commitment to disguise herself as one of her subjects (often poor workers) and immerse herself in their lifestyle.

In 1890 Potter needed historical information for an upcoming book on London sweatshops and was referred to socialist and reformist Sidney Webb. Webb fell in love with her but she rejected his proposals for marriage until it became apparent that they were deeply intellectually compatible. They married in 1892 and wrote their first of many books together, The History of Trade Unionism (1894). Personal friend H.G. Wells once described the Webbs as “the most formidable and distinguished couple conceivable” (Oxford Companion to English Literature, 1995).

The Webbs’ influence on British government is still felt. Beatrice was among the first to conceive of a “national health plan,” the basis for the National Health Service. She also apprenticed with Charles Booth, helping him write the influential study The Life and Labour of the People in London (1902-03). In opposition to Britain’s 1934 Poor Law, the Webbs wrote a minority report which helped lay the foundation of Britain’s social services system.

After joining the Fabian Society in the 1890s, the Webbs socialized with other freethinkers. Along with George Bernard Shaw and Graham Wallas, the Webbs founded The London School of Economics and Political Science in 1895 to train social scientists to promote “the betterment of society.” The Webbs both held government posts throughout their later years. Together, they published around 500 books, articles, pamphlets and edited volumes. They are interred together in the nave of Westminster Abbey. D. 1943.

PHOTO: Webb in 1875.

“That part of the Englishman’s nature which has found gratification in religion is now drifting into political life.”

— Webb, quoted in "100 Years of Freethought" by David H. Tribe (1967)

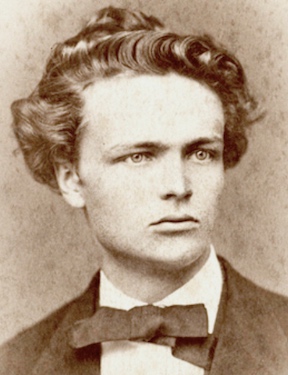

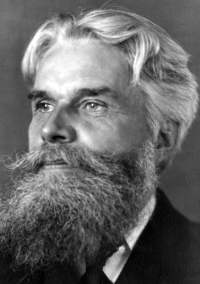

Johan August Strindberg

On this date in 1849, dramatist and novelist Johan August Strindberg, one of nine children, was born in Stockholm, Sweden. His family was poor, as demonstrated by the title of his autobiography, The Son of a Servant (1886). He attended Upsala University and, while working at the Royal Library in Stockholm, wrote a popular novel, Roda rummet (1879), which made him a national celebrity. The author of more than 70 plays, he is considered an important influence to modern playwrights.

His 1882 religious satiric story, Det nya riket (The New Kingdom), created such a ruckus he had to leave the country. When he returned he became an active leader with the Swedish Rationalists. He corresponded with Nietzsche and was an admirer of Edgar Allan Poe. A passage with an unorthodox description of the Last Supper in his collection of his stories, Giftas (1884), was censored as anti-Christian and Strindberg was charged with blasphemy.

Although in Switzerland at the time, he returned to Sweden to face charges and was acquitted. He suffered a mental breakdown, which he never really recovered from, in the late 1890s, although he remained active in theater. (D. 1912)

PHOTO: Strindberg at age 25.

“Reason, too, was sin; the greatest of all sins, for it questioned God’s very existence, tried to understand what was not meant to be understood. Why it was not meant to be understood was not explained; probably it was because if it had been understood the fraud would have been discovered.”

— Strindberg, "Married" ("Giftas"), 1884

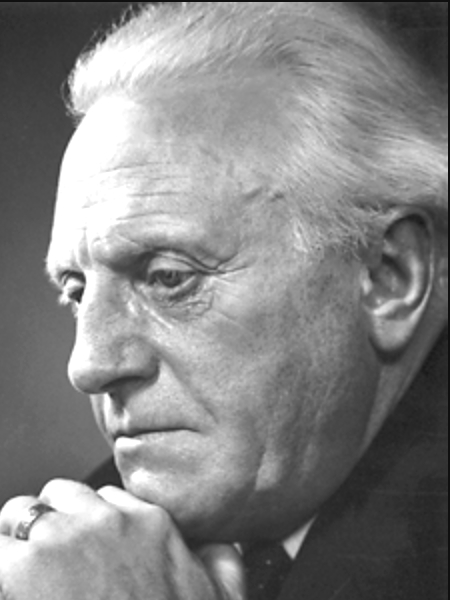

W. Somerset Maugham

On this date in 1874, William Somerset Maugham was born in Paris, where his father was an attorney with the British Embassy. He was orphaned by the time he was 10 after his father died of cancer and his mother of tuberculosis. He underwent medical training at St. Thomas Hospital in London, becoming a doctor in 1897. After publishing his first novel, Liza of Lambeth (1897), Maugham left his medical career to pursue writing. His literary skill and concise writing style helped him become an accomplished novelist, playwright and short-story writer.

He is most famous for writing the semi-autobiographical novel Of Human Bondage (1917). His other popular works include The Moon and Sixpence (1919), Cakes and Ale (1930), The Razor’s Edge (1944) and the short story “Rain” (1923). He married Syrie Wellcome following her divorce from Henry Wellcome in 1917. The marriage was unhappy and they divorced in 1928. They had one daughter, Mary Elizabeth, born in 1915. Many of Maugham’s significant relationships were with men. Frederick Gerald Haxton, his American secretary, was his lover and companion from 1914 until Haxton’s death in 1944.

Maugham was a nonbeliever who saw no need for religion. “I remain an agnostic, and the practical outcome of agnosticism is that you act as though God did not exist,” he wrote in his memoir The Summing Up (1938). In the notebook he kept from 1892-1949, he discussed his lack of religious beliefs more extensively: “I’m glad I don’t believe in God. When I look at the misery of the world and its bitterness I think that no belief can be more ignoble.” (A Writer’s Notebook, 1949.)

He continued in his notebook: “The evidence adduced to prove the truth of one religion is of very much the same sort as that adduced to prove the truth of another. I wonder if that does not make the Christian uneasy to reflect that if he had been in Morocco he would have been a Mahometan, if in Ceylon a Buddhist; and in that case Christianity would have seemed to him as absurd and obviously untrue as those religions seem to the Christian.” (D. 1965)

“I do not believe in God. I see no need of such idea. It is incredible to me that there should be an after-life. I find the notion of future punishment outrageous and of future reward extravagant. I am convinced that when I die, I shall cease entirely to live; I shall return to the earth I came from.”

— Maugham, "A Writer’s Notebook" (1949)

Virginia Woolf

On this date in 1882, novelist and essayist Virginia Woolf, née Adeline Virginia Stephen, the daughter of freethinker Sir Leslie Stephen and Julia Jackson Duckworth, was born in London. Starting at an early age, she and her sister Vanessa were sexually abused by two half-brothers. Woolf’s mother died when she was in her early teens, followed by the death of her caretaking half-sister Stella, then her father from a slow cancer in 1904 and finally her brother Toby in 1906.

Woolf had the first of several major breakdowns following Toby’s death. She moved into the home of her sister Vanessa and her husband Clive Bell in Bloomsbury, which became the hub of the intellectual and largely freethinking Bloomsbury group. In 1905 she began working for the Times Literary Supplement. She married Leonard Woolf in 1912.

Her first book, The Voyage Out, was published in 1915, followed by Night and Day (1919), Jacob’s Room (1922), Mrs. Dalloway (1925) and Orlando (1938). Woolf wrote more than 500 essays, among them “A Room of One’s Own” (1929), in which she famously observed, “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” Her “Three Guineas” was likewise a feminist rallying cry to women to come into their own.

Woolf pioneered the modern novel, employing stream-of-consciousness and a non-linear narrative. Orlando featured an androgynous protagonist, reputedly inspired by Vita Sackville-West, with whom she had a love affair. Woolf committed suicide by drowning herself during a recurring period of mental breakdown and despair in early World War II, writing her husband: “I owe all my happiness to you but can’t go on and spoil your life.” (D. 1941)

“I read the Book of Job last night — I don’t think God comes well out of it.”

— letter to Lady Robert Cecil, Nov. 12, 1922, "The Letters of Virginia Woolf, Vol. 2," eds. N. Nicolson and J. Trautmann (1976)

Jules Feiffer

On this date in 1929, cartoonist, playwright and author Jules Ralph Feiffer was born in the Bronx, New York to David Feiffer, an unsuccessful men’s shop entrepreneur, and Rhoda (Davis) Feiffer, who sold dress designs and largely supported their family.

His weekly editorial cartoons appeared in the Village Voice for 42 years. Feiffer won the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning in 1986. His cartoons have been published in 19 books. He was named to the Comic Book Hall of Fame in 2004.

Feiffer’s anti-military animated cartoon “Munro” won an Academy Award in 1961. His comedy “Little Murders” (1967) won an Obie. Among his other plays and revues is “Knock Knock,” which had a 1976 Broadway run starring Lynn Redgrave. Feiffer wrote the screenplay for the film “Carnal Knowledge” (1971), which spawned censorship and lawsuits.

Feiffer was married three times and had three children. His daughter Halley Feiffer is an actress and playwright. In 2016 he married freelance writer Joan “JZ” Holden. The ceremony combined Jewish and Buddhist traditions. She is the author of Illusion of Memory (2013).

He died of congestive heart failure nine days before his 96th birthday at his home in Richfield Springs, N.Y. (D. 2025)

PHOTO: Feiffer reading at Politics and Prose in 2018 in Washington, D.C. Photo by SLOWKING under CC BY-NC.

“Christ died for our sins. Dare we make his martyrdom meaningless by not committing them?”

— Lines from Feiffer's play "Little Murders," first performed on and off Broadway in the late 1960s

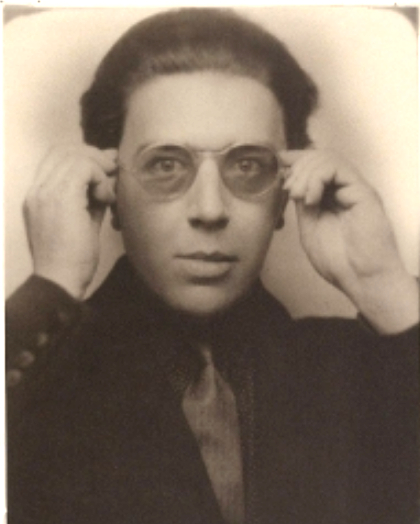

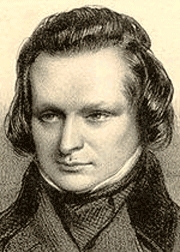

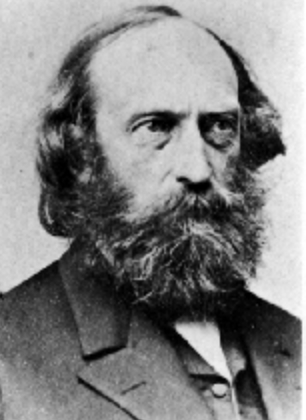

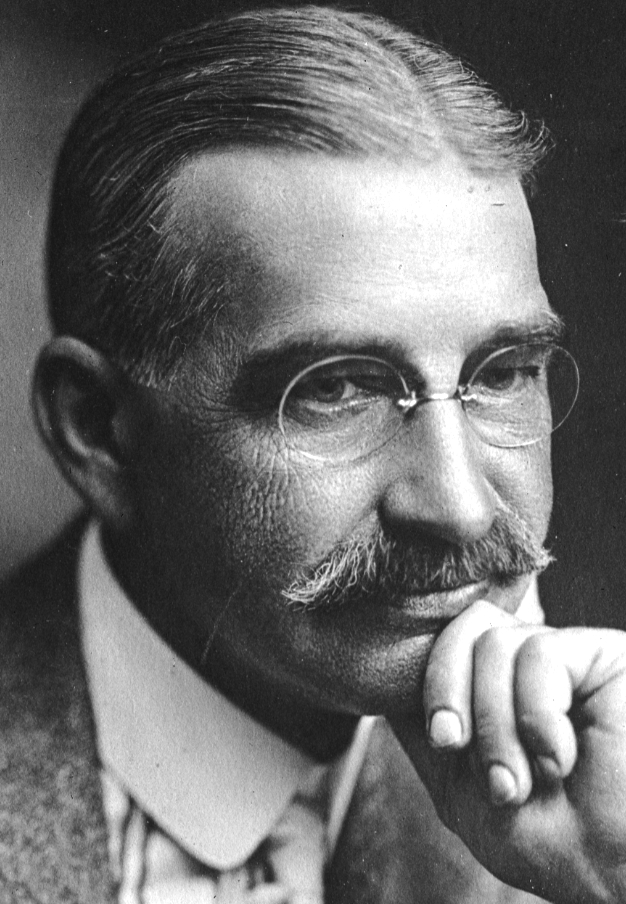

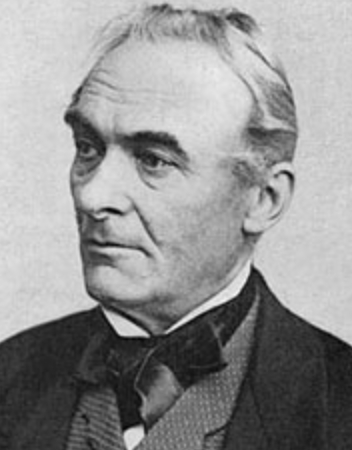

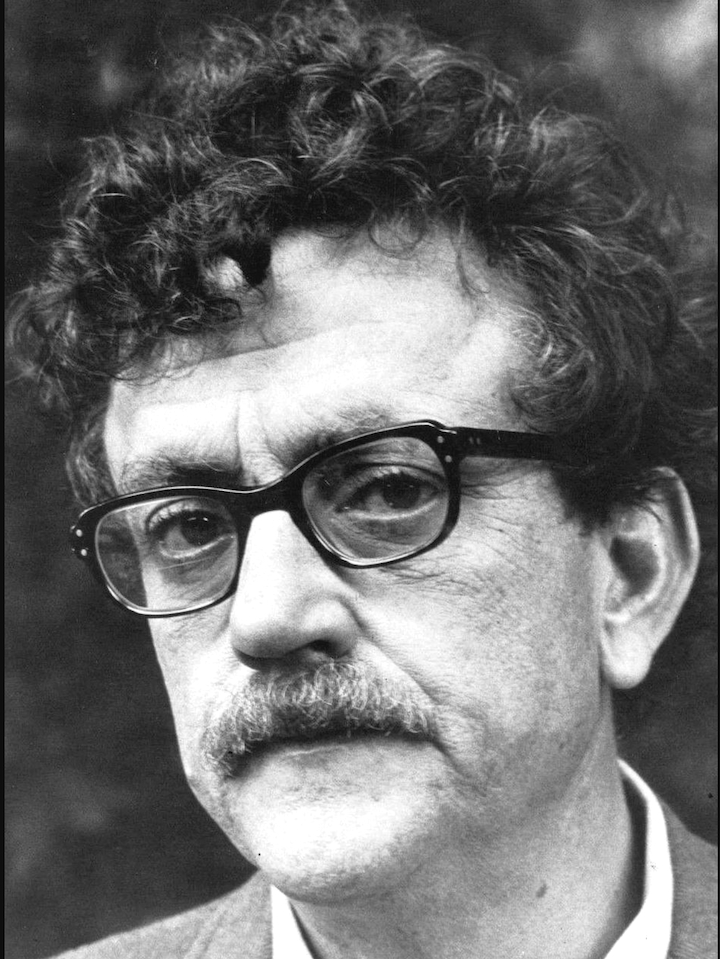

David Friedrich Strauss

On this date in 1808, theologian and author David Friedrich Strauss was born in Ludwigsburg, Germany, the son of a merchant. He pioneered scholarship questioning the historicity of Jesus. Strauss became a Lutheran vicar in 1830 and studied theology under Hegel. He was appointed to the Theological Seminary at the University at Tubingen. His two-volume work Das Leben Jesu kritisch bearbeitet (The Life of Jesus Critically Examined (1835) dissected the New Testament as largely mythical and was published to great acclaim but lost him his teaching post. The British freethinking novelist George Eliot translated its fourth edition in 1860 into English.

In 1836 he left the church. In 1841 he married mezzo-soprano opera singer Agnese Schebest. They divorced in 1846 after having two children. In his final book, The Old Faith and the New: A Confession (1872), Strauss eschewed Christianity and the concept of immortality to embrace materialist philosophy. (D. 1874)

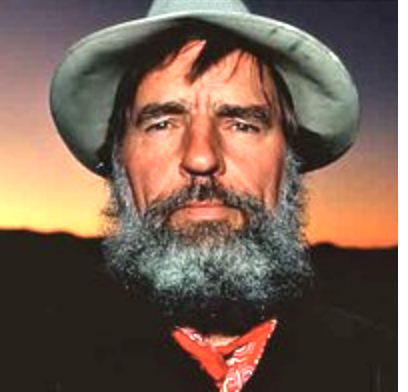

Edward Paul Abbey

On this date in 1927, author Edward Paul Abbey was born in Indiana, Pa., to Mildred (Postlewait) and Paul Abbey, the eldest of five siblings. Both were hardworking, independent persons, and while Mildred was a lifelong liberal Presbyterian, Paul was more radical, declaring himself an atheist and a socialist as a young adult. Edward Abbey served in the U.S. Army as a military police officer in Italy and then enrolled at the University of New Mexico, where he earned a B.A. in philosophy and English in 1951 and a master’s in philosophy in 1956. He married Jean Schmechal, the first of his five wives (with whom he had five children), as an undergrad. He was removed as editor of the student newspaper for putting Diderot’s famous quote, “Man will never be free until the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest,” on the cover of one issue.

He worked as a welfare caseworker, teacher, bus driver and technical writer before starting a career as a ranger and fire lookout at several national parks or monuments. His two seasons at Arches National Monument (later a national park) near Moab, Utah, in 1956-57 provided the grist for the book that brought him acclaim, Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness (in 1968), a nonfiction work that was preceded by three novels. His 1975 comic novel The Monkey Wrench Gang, about a group of ecological saboteurs is perhaps his best-known work. While he wrote primarily about environmental issues and land-use policies, Abbey was basically a political anarchist, and according to Wilderness.net, “he wasn’t comfortable with environmental activists or activism as a whole.”

His best friend Jack Loeffler recorded Abbey’s thoughts on religion after their 1983 camping trip in the Superstition Mountains of Arizona, included in his 1989 book Headed Upstream: Conversations with Iconoclasts, in which Abbey said, “I regard the invention of monotheism and the otherworldly God as a great setback for human life.” Abbey himself roundly condemned religion in his own works, particularly in A Voice Crying in the Wilderness, published in 1989, the year he died of esophageal hemorrhaging after surgery for a congenital circulatory disorder. “What is the difference between the Lone Ranger and God?” Abbey asked, before answering, “There really is a Lone Ranger.”

“Whatever we cannot easily understand we call God; this saves much wear and tear on the brain tissues.”

— "A Voice Crying in the Wilderness: Notes from a Secret Journal" (1989)

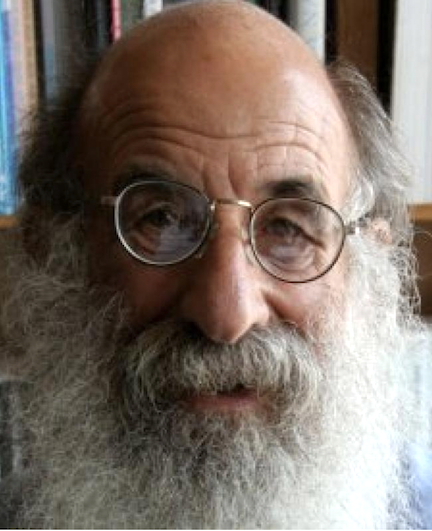

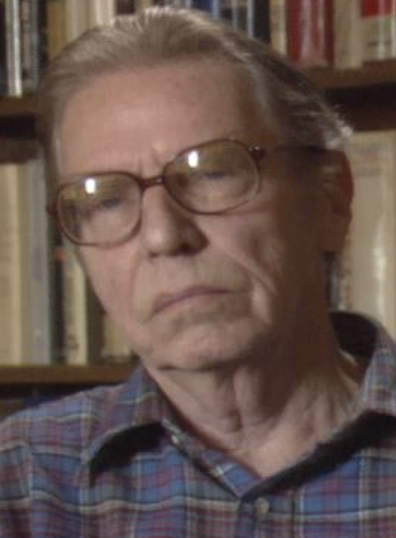

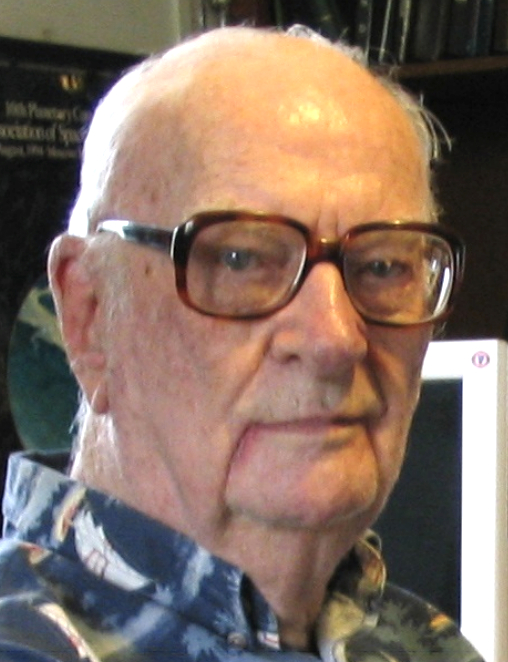

Victor Stenger

On this date in 1935, particle physicist, author and skeptic Victor John Stenger was born in Bayonne, New Jersey. Stenger, the son of a first-generation Lithuanian immigrant and a second-generation Hungarian immigrant, grew up in a Catholic neighborhood. He earned a bachelor’s in electrical engineering from Newark College of Engineering and a master’s in physics from UCLA, followed by a Ph.D. After taking a position on the University of Hawaii faculty, Stenger began a long and influential career during one of the most exciting times for physics in history.

His experiments helped establish standard models in physics, examining and uncovering the properties of quarks, gluons, neutrinos and “strange” particles. Stenger also made contributions to the emerging fields of high-energy gamma ray and neutrino astronomy. In his last major research endeavor before retiring in Colorado in 2000, Stenger collaborated on a project in Japan that demonstrated for the first time that the neutrino has mass. The project’s head researcher won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2002.

In addition to his numerous and influential peer-reviewed articles, Stenger wrote 12 books, including the 2007 bestseller God: The Failed Hypothesis: How Science Shows that God Does Not Exist. Some of his other titles include Not By Design: The Origin of the Universe (1988), The Unconscious Quantum: Metaphysics in Modern Physics and Cosmology (1995), The New Atheism: Taking a Stand for Science and Reason (2009), The Fallacy of Fine-Tuning: Why the Universe Is Not Designed for Us (2011), and God and the Folly of Faith: The Fundamental Incompatibility of Religion and Science and Why It Matters (2012).

Stenger’s work hinged on the interplay between philosophy, particle physics, quantum mechanics and religion. He was a self-professed skeptic and atheist, maintaining that all things in existence — including consciousness and the subjective illusion of libertarian free will — may be revealed and described by rational scientific inquiry without resorting to supernatural explanations, the meaning of which are empty, useless, unproductive and put a crippling end to intellectual progress.

In order to champion these causes, Stenger pursued public speaking, debating prominent Christian apologists and participating in the 2008 “Origins Conference” hosted by the Skeptics Society. Stenger was a member of a number of skeptics and humanist organizations, including presidential stints with the Hawaiian Humanists from 1990-94 and the Colorado Citizens for Science from 2002-06.

He was an honorary director of FFRF, a member of the Society of Humanist Philosophers and the Free Inquiry editorial board, and a fellow of the Center for Inquiry and the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Among a number of visiting positions, Stenger was an adjunct professor of philosophy at the University of Colorado and an emeritus professor of physics at the University of Hawaii. Stenger lived with his wife Phylliss, whom he married in 1962. They had two children. (D. 2014)

PHOTO: Licensed under CC BY 3.0.

“Science flies you to the moon. Religion flies you into buildings.”

— Stenger, who suggested this slogan post-9/11 after ideas for bus signs were solicited by the Richard Dawkins Foundation.

Robin Morgan

On this date in 1941, Robin Morgan — feminist author, journalist, editor, lecturer, organizer, atheist and activist — was born in New York City. As she notes in her memoir, Saturday’s Child, “Saturday’s child has to work for a living.” She started at age 2 as a tot model. She had her own radio show by age 4, then acted in the role of Dagmar on the popular series “Mama” in the 1940s and 1950s. She left show biz to write and became a founder and leader of the contemporary feminist movement.

Morgan’s columns and articles for Ms. magazine appeared from 1974-88. She was editor-in-chief of Ms. for four years and later its international consulting editor. Her groundbreaking anthology Sisterhood Is Powerful came out in 1972, followed by Sisterhood Is Global (1984), Sisterhood Is Forever (2003) and Fighting Words: A Toolkit for Combating the Religious Right (2006). Morgan is a distinguished poet and the author of more than 20 books, including her 2006 novel The Burning Time, based on the first witchcraft trial in Ireland.

She has traveled the globe as a feminist activist, scholar, journalist and lecturer. She is a co-founder of the Feminist Women’s Health Network, the Feminist Writers’ Guild, Media Women and the National Network of Rape Crisis Centers. Her timely The Demon Lover: On the Sexuality of Terrorism tells the personal story of her travel to refugee camps in the Middle East, with a post-9/11 introduction and afterword. A recipient of many awards, she was named FFRF’s Freethought Heroine in 2005 and is an honorary director.

She was married from 1962-83 to poet Kenneth Pitchford, a founding member of the Effeminist movement. He and Morgan, who are both bisexual, have a son, musician Blake Morgan.

She was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2010. Instead of curtailing her effectiveness, the diagnosis inspired her to take the lead in creating the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation’s Women and PD Initiative to help women be better served by research, treatment and assistance for their caregivers. Morgan has shared her struggle with the disease by writing and presenting about her experiences at a variety of venues, including her 2015 Ted Talk, viewed over a million times. In 2018 she published Dark Matter: New Poems, which includes the verses from that presentation.

“Religion is not about awe and joy, despite its purported proprietorship of these and its promise to eventually deliver what already lies around us every day, freely available for utter celebration. Religion is about something else. The etymology of the word itself, from the Latin, to being ‘bound by rules.’ Religion is about terror.”

— Freethought Heroine acceptance speech at FFRF's national convention (Nov. 11, 2005)

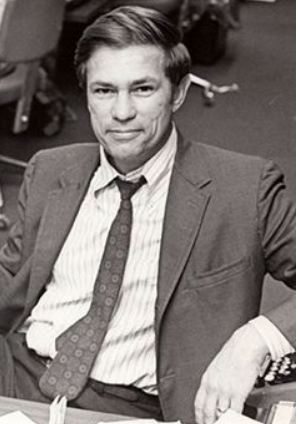

Jack Germond

On this date in 1928, journalist John Worthen “Jack” Germond was born in Newton, Mass. Germond wrote several books, mainly focusing on politics. After serving in the U.S. Army in 1946-47, he earned a B.A. and B.S. from the University of Missouri. He graduated in 1951 and began writing for the Rochester, N.Y., Times-Union, eventually heading its Washington bureau. He was the Washington Star’s political editor from 1974-81 and wrote a syndicated column on national politics for 24 years with fellow journalist Jules Witcover.

He moved to the Baltimore Sun when the Star folded. He first appeared on NBC’s “Meet the Press” in 1972 and “The Today Show” in 1980 and on PBS’ “The McLaughlin Group” in 1981. Germond tended to be liberal politically and was seen by many as in touch with the average American and as a traditional “old-school” newspaper reporter.

His books included Fat Man Fed Up: How American Politics Went Bad (2005), Fat Man in the Middle Seat: Forty Years of Covering Politics (2002), Mad as Hell: Revolt at the Ballot Box, 1992 (1994), Whose Broad Stripes and Bright Stars? (1989) and Blue Smoke and Mirrors: How Reagan Won and Why Carter Lost the Election of 1980 (1981). He co-wrote his earlier books with Witcover. He had two daughters with his first wife, Barbara Wipple. Their daughter Mandy died at age 14 from leukemia. After a 1988 divorce he married Alice Travis, a Democratic Party official and political activist. (D. 2013)

“In the interests of full disclosure, I must note that although I was brought up as a Protestant, I have been an atheist my entire adult life. I do not proselytize, however. Nor do I question the faith of others. I just don’t want to be obliged to accept someone else’s faith as a factor in my government. If John Ashcroft wants to hold a prayer meeting and advertise his piety, let him find someplace besides the Justice Department.”

— Jack Germond, "Fat Man Fed Up” (2005)

Ayn Rand

On this date in 1905, Ayn Rand (née Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum) was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, to a nonobservant Jewish family. She became an atheist as a teenager. Immigrating to the United States in 1921, she renamed herself Ayn (rhymes with “mine”) after a Finnish woman; the “Rand” was inspired by her Remington-Rand typewriter. She worked for Hollywood studios intermittently for 20 years, starting as an extra for Cecil B. DeMille and progressing to screenwriter. She married actor Frank O’Connor in 1929 in “a ‘proper’ nonreligious ceremony in a judge’s chambers.”

Rand’s first novel We the Living (1936) was not initially successful. The Fountainhead (1943) secured her place in literature, followed by Atlas Shrugged (1957). Rand’s novels promote her philosophy of Objectivism, promulgated in John Galt’s famous speech from Atlas Shrugged. Galt termed faith “a short-circuit destroying the mind.” Rand’s lecture “Faith and Force: the Destroyers of the Modern World” was delivered at Yale University in 1960.

During her lifetime, Rand’s writing provoked praise and condemnation, but more of the latter. In 2009, GQ critic Tom Carson described her books as “capitalism’s version of middlebrow religious novels” such as Ben-Hur and the “Left Behind” series. After undergoing surgery for lung cancer in 1974, she died of heart failure in 1982.

“The human race has only two unlimited capacities: one for suffering and one for lying. I want to fight religion as the root of all human lying and the only excuse for human suffering.”

— "Journals of Ayn Rand," ed. David Harriman (1997)

Havelock Ellis

On this date in 1859, sexologist Henry Havelock Ellis was born in Croydon, south London, England. He had four sisters, none of whom married. His father was a sea captain, his mother the daughter of a sea captain. Initially an educator, he returned to school to earn a medical degree but never set up a practice.

He wrote notably on the psychology of sex and criminal reform. His writings include Man and Woman (1894), Sexual Inversion (1897), which advanced the idea that homosexuality is not a disease or a crime, and Affirmations (1898) where his agnostic views are found. He was very conversant with the bible and believed it to be a work of great value.

Ellis studied what today are called transgender phenomena. His landmark six-volume Studies in the Psychology of Sex, was published between 1897-1910. His views were considered so controversial that a bookseller was arrested for selling one of his books.

In November 1891, at the age of 32 and reportedly still a virgin, Ellis married writer and feminist Edith Lees, an open lesbian. Their “open marriage” was the central subject in his autobiography My Life (1939). It’s believed he had an affair with Margaret Sanger.

He died at age 80 in 1939. His wife died of diabetes-related causes in 1916 at age 55. (D. 1939)

“Had there been a Lunatic Asylum in the suburbs of Jerusalem, Jesus Christ would infallibly have been shut up in it at the outset of his public career. That interview with Satan on a pinnacle of the Temple would alone have damned him, and everything that happened after could have confirmed the diagnosis.”

— Ellis, "Impressions and Comments" (1914)

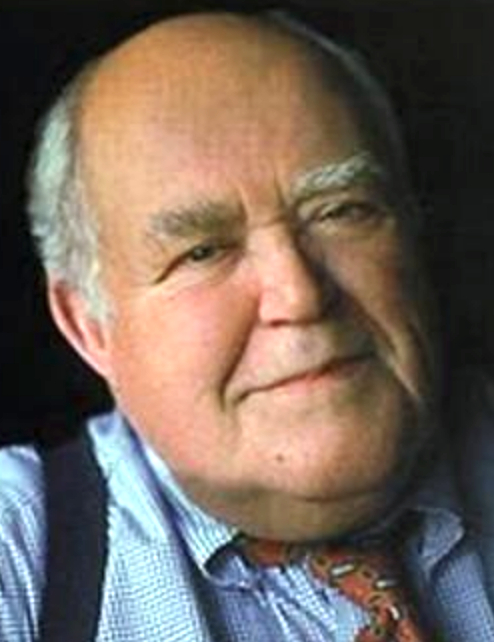

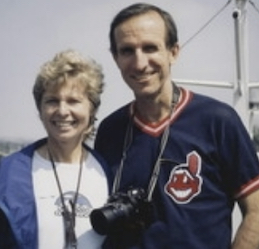

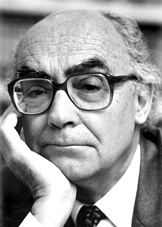

James A. Michener

On this date in 1907, writer James Albert Michener was born in New York City. An orphan, he spent his first few years at the Bucks County Poorhouse in Doylestown, Pa, until adopted by Edwin and Mabel Michener. As Quakers, they believed in social activism and took in several orphaned children. The family was extremely poor, moving often during Michener’s childhood. He felt that this gave him a strong sense of character, an acceptance of what life really looked like.

In an interview with the American Academy of Achievement, Michener stated, “I think the bottom line … is that if you get through a childhood like mine, it’s not all bad. … The sad part is, most of us don’t come out.” Michener credited his mother for reading to him every night. “I had all the Dickens and Thackeray and Charles Read and Sinkiewicz and the rest before I was the age of seven or eight.”

Michener realized at a young age that there was a bigger world to see and, when he was 14, started hitchhiking around the U.S. with only 35 cents in his pocket: “I went everywhere, and I did it on nothing.” This interest in the world lasted a lifetime. Michener received a scholarship to study at Swarthmore College, graduating with highest honors. He studied at St. Andrew’s University in Scotland, returned home to teach, and then went on to become assistant visiting professor of history at Harvard University.

At the onset of World War II, Michener joined the Navy and was stationed in the Pacific. In 1947 he wrote his first book, Tales of the South Pacific, relating some of his experiences in the Solomon Islands, for which he received a Pulitzer Prize. The story was subsequently turned into the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, “South Pacific,” which also received a Pulitzer.

Spending many years living abroad and writing, he thoroughly researched whichever culture he was living in before he started writing. Among his books are: The Bridges at Toko-Ri, Sayonara, The Source (about religion), Hawaii, Chesapeake, The Covenant, Space, Poland, Texas and Alaska. Michener was also active in public service, was a member of the Advisory Council to NASA and was cultural ambassador to various countries. He considered himself to be a humanist, and during the 1960s spoke out, amid the concerns raised regarding John F. Kennedy’s Catholicism: “I’ve fought to defend every civil right that has come under attack in my lifetime. … I’ve stood for absolute equality, and it would be ridiculous for a man like me to be against a Catholic for President.” (The Historian, 2001)

Michener won several honors and awards, among them the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian award. He was married three times — to Patti Koon from 1935 to 1948, when they divorced, to Vange Nord from 1948 to 1955, when they divorced, and to Mari Yoriko Sabusawa from 1955 to 1994, when she died.

He died of kidney disease at age 90 in Austin, Texas. (D. 1997)

PHOTO: Michener in 1991 at the 50th anniversary observance of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

“I am terrified of restrictive religious doctrine, having learned from history that when men who adhere to any form of it are in control, common men like me are in peril. I do not believe that pure reason can solve the perceptual problems unless it is modified by poetry and art and social vision. So I am a Humanist. And if you want to charge me with being the most virulent kind — a secular humanist — I accept the accusation.”

— Michener interview, Parade magazine (Nov. 24, 1991)

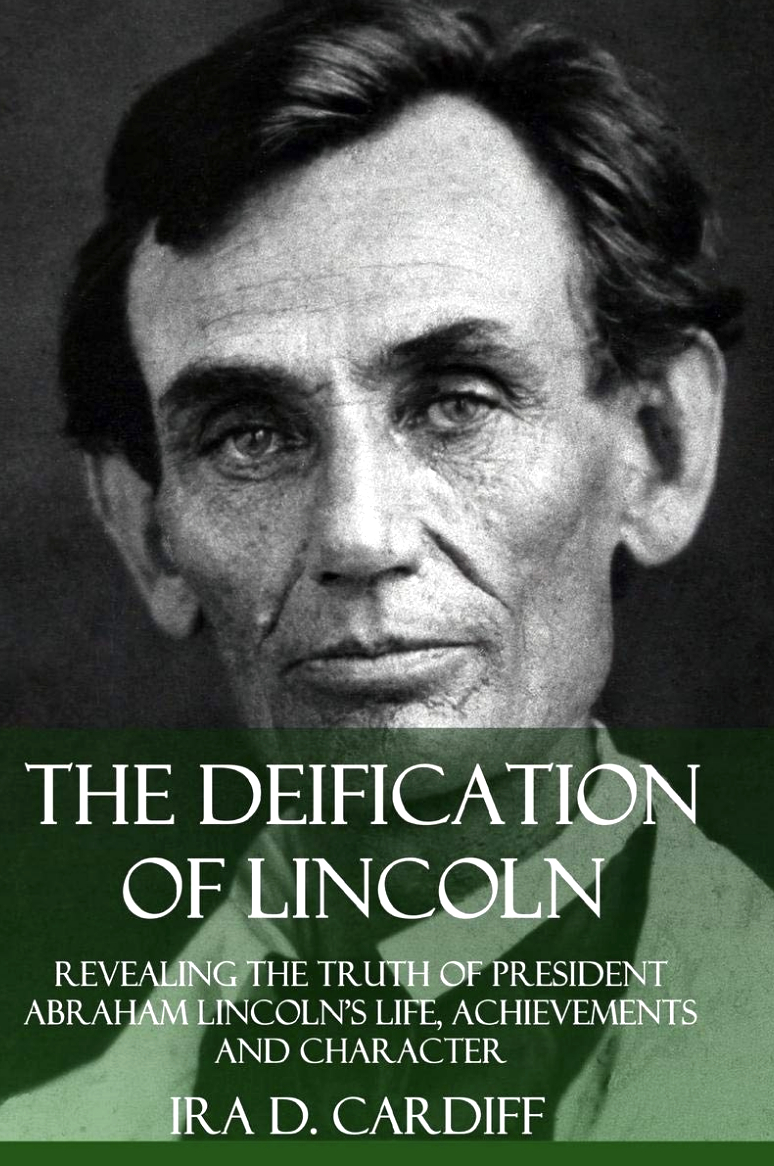

Sinclair Lewis

On this date in 1885, Harry Sinclair Lewis was born in Sauk Centre, Minn. The novelist wrote such enduring classics as Main Street (1920), Babbitt (1922), Arrowsmith (1925) and the irreverent Elmer Gantry (1927). The title character, a preacher, is portrayed as a rogue and hypocrite who steals freethinker Robert G. Ingersoll’s “Love” as his signature sermon.

Lewis’ other books include It Can’t Happen Here (1935) and The God-Seeker (1949). An unbeliever since his days at Yale, from which he graduated in 1908, Lewis was married twice and had one son. In 1930 he became the first American to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature “for his vigorous and graphic art of description and his ability to create, with wit and humour, new types of characters.” (He had refused an earlier Pulitzer Prize.)

In his autobiographical sketch for the Nobel committee, Lewis noted that although he traveled widely, he had “lived a quite unromantic and unstirring life.” He was dubbed “the conscience of his generation” by Sheldon Norman Grebstein. (D. 1951)

“It is, I think, an error to believe that there is any need of religion to make life seem worth living.”

— Lewis, quoted by Will Durant in "On the Meaning of Life" (1932)

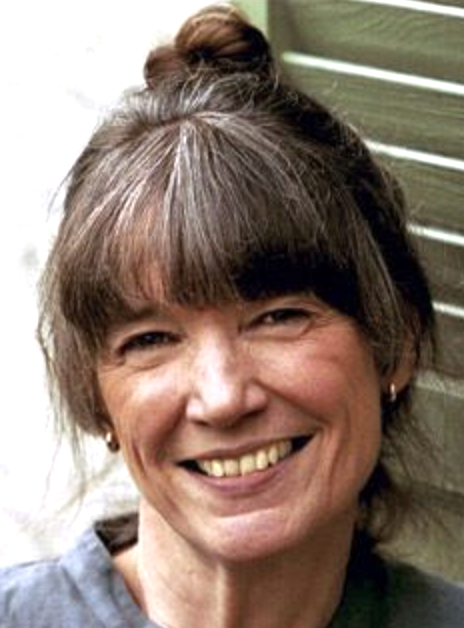

Alice Walker

On this date in 1944, novelist, poet and self-described “Earthling” Alice Malsenior Tallulah-Kate Walker was born in Eatonton, Georgia, the youngest of eight children in a sharecropping family. Blinded in one eye during a childhood accident, she went on to become valedictorian at her high school and attended both Spelman College and Sarah Lawrence College on scholarships. Walker graduated from Sarah Lawrence in 1965. She worked on voter registration drives in the 1960s and married fellow civil rights worker Melvyn Leventhal in 1967. They had a daughter, Rebecca, in 1970 and divorced in 1976.

Her first book of poetry was published in 1970. Walker edited I Love Myself When I Am Laughing and Then Again When I Am Looking Mean and Impressive: A Zora Neale Hurston Reader in 1979, introducing and popularizing Hurston to a new generation.

The Color Purple, Walker’s bestselling 1982 novel, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1983 and was turned into a popular movie by Steven Spielberg. Walker introduced the term “womanist” to the feminist movement to describe African-American feminism. Her books of essays include In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens: Womanist Prose (1983), Alice Walker Banned (1996) and Anything We Love Can Be Saved: A Writer’s Activism (1997).

Walker’s views on religion are expressed in “The Only Reason You Want to Go to Heaven Is That You Have Been Driven Out of Your Mind (Off Your Land and Out of Your Lover’s Arms): Clear Seeing Inherited Religion and Reclaiming the Pagan Self” (anthologized in Anything We Love Can Be Saved). Raised as a Methodist by devout parents, early in life she observed church hypocrisy, especially the silencing of the women who cleaned the church and kept it alive. “Life was so hard for my parents’ generation that the subject of heaven was never distant from their thoughts. … The truth was, we already lived in paradise but were worked too hard by the land-grabbers to enjoy it.”

In The Color Purple, the protagonist rebels against a God who [vernacular ahead] “act just like all the other mens I know. Trifling, forgitful and lowdown.” Walker, rebelling against the misogyny of Christian teachings and the imposition of a white religion upon the enslaved, wrote: “We have been beggars at the table of a religion that sanctioned our destruction.”

Walker added: “All people deserve to worship a God who also worships them. A God that made them, and likes them. That is why Nature, Mother Earth, is such a good choice. Never will Nature require that you cut off some part of your body to please It; never will Mother Earth find anything wrong with your natural way.”

“It is chilling to think that the same people who persecuted the wise women and men of Europe, its midwives and healers, then crossed the oceans to Africa and the Americas and tortured and enslaved, raped, impoverished, and eradicated the peaceful, Christ-like people they found. And that the blueprint from which they worked, and still work, was the Bible.”

— "Anything We Love Can Be Saved" (1997)

Amy Lowell

On this date in 1874, poet Amy Lawrence Lowell was born in Brookline, Mass. Her father, a cousin of James Russell Lowell, was also related to Robert Lowell. Amy grew up in a house her father dubbed “Sevenels” (because seven Lowells lived there). Lowell at first had a British governess and became famous in her family for her creative misspellings. As a popular debutante, known for her dancing and conversational style, she had no less than 60 dinners thrown for her.

Because it was not considered “proper” by her family for young women to go to college, she was denied a higher education, but made use of her family’s extensive library to educate herself. After a failed engagement and growing obesity, probably stemming from a glandular condition, Lowell was exiled to Egypt in 1897-98 to help her forget her troubles and also lose weight. The imposed spartan regimen nearly killed her.

She started writing poetry in 1902 and met actress Ada Dwyer Russell in 1912, with whom she had a “Boston marriage” for the rest of her life. Her first of several books of poems, Men, Women & Ghosts, was published in 1916. Lowell wrote Tendencies in Modern American Poetry (1917). Her biography of John Keats appeared in 1925. What’s O’Clock, posthumously published in 1925, was awarded a $1,000 Pulitzer Prize for the best volume of verse published during the year by an American author.

Lowell penned more than 650 poems before her death from a cerebral hemorrhage at age 51. (D. 1925)

And every year when the fields are high

With oat grass, and red top, and timothy,

I know that a creed is the shell of a lie.— Lowell's poem "Evelyn Ray" from "What's O'Clock" (1925)

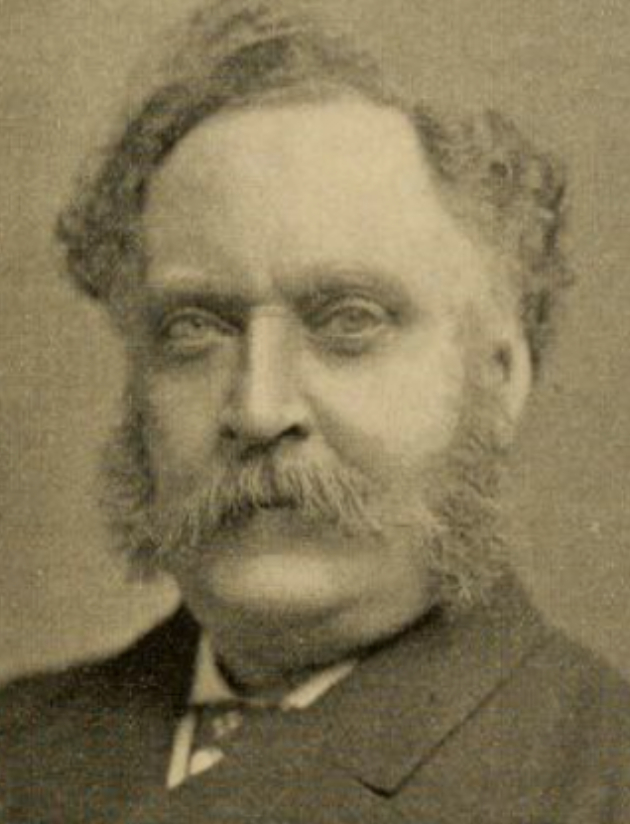

James Parton

On this date in 1822, biographer James Parton was born in Canterbury, England. His father died when he was 4 and he moved with his mother and siblings to New York the next year. He became a schoolmaster in Philadelphia and New York. He joined the staff of the Home Journal in 1848. After writing The Life of Horace Greeley (1855), Parton turned to biography and lecturing. He became a U.S. citizen in 1845.

His many biographies include Life and Times of Aaron Burr (1857), Life of Andrew Jackson (1859-61), Life of Voltaire (2 vols., 1881), Noted Women of Europe and America (1883) and biographies of such deists as Jefferson and Franklin. His first wife, Sara, whom he married in 1856, was a popular novelist under the nom de plume Fanny Fern. (D. 1891)

“In the days when to be an Agnostic was to be almost an outcast, [Parton] had the heart to say of the Mysteries that he did not know.”

— W.D. Howells, "Literary Friends and Acquaintance" (1901)

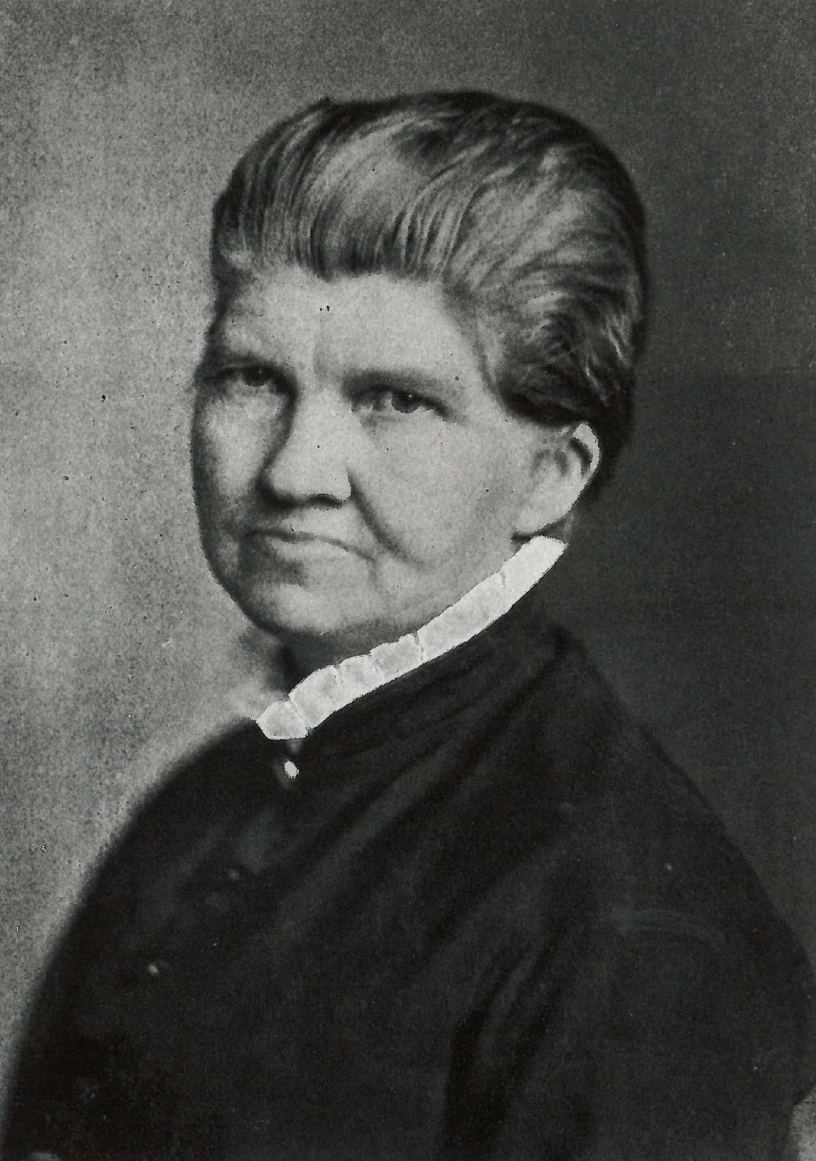

Lydia Maria Child

On this date in 1802, Lydia Maria Child (née Francis) was born in Medford, Mass. Considered one of the first U.S. “women of letters,” she became a famous abolitionist, author, novelist and journalist. Her poem “Over the River and Through the Wood” (originally titled “A Boy’s Thanksgiving Day”) became popular as a song: “Over the river and through the wood / to grandfather’s house we go.” After her mother died when she was 12, she went to live with her older married sister in Maine and studied to become a teacher.

She ran a private school, started the first journal for children and wrote several novels and popular how-to books such as The Frugal Housewife, The Mother’s Book and The Little Girl’s Own Book. Her history, The First Settlers of New England, blamed Calvinist-based racism for the treatment of Native Americans. She married David Childs, editor and publisher of the Massachusetts Journal, in 1828 when she was 26.

An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans recruited many to the anti-slavery movement, but made Child a pariah in Boston society. Her two-volume The History of the Condition of Women, in Various Ages and Nations was published in 1835. She continued abolition work, supporting herself through popular writings and newspaper columns. The Progress of Religious Ideas (1855) rejected theology, dogma, doctrines, and talked of “Providence” as the inward voice of conscience. Her funeral was presided over by Wendell Phillips, who said she was “ready to die for a principle and starve for an idea.” John Greenleaf Whittier recited a poem in her honor and The Truth Seeker memorialized her. D. 1880.

“It is impossible to exaggerate the evil work theology has done in the world.”

— Child, "The Progress of Religious Ideas Through Successive Ages" (1855)

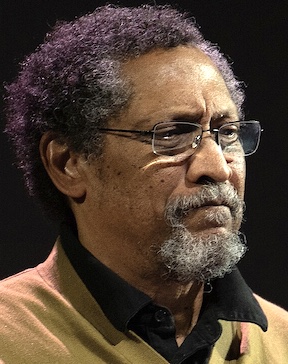

Sikivu Hutchinson

On this date in 1969, Black activist, author and feminist Sikivu Hutchinson was born in Los Angeles to Yvonne (Divans) and Earl Ofari Hutchinson Jr., respectively a retired English teacher and a noted analyst and commentator on race, politics and civil rights. Her grandfather, Earl Hutchinson Sr., published his autobiography A Colored Man’s Journey Through 20th Century Segregated America when he was 96.

Hutchinson earned a B.A. in anthropology from UCLA and a Ph.D. in performance studies from New York University in 1999. She taught women’s studies, cultural studies, urban studies and education at UCLA, the California Institute of the Arts and Western Washington University.

Her first book was Imagining Transit: Race, Gender, and Transportation Politics in Los Angeles (2003) and was followed by Moral Combat: Black Atheists, Gender Politics, and the Values Wars (2011), Godless Americana: Race and Religious Rebels (2013) and Humanists in the Hood: Unapologetically Black, Feminist, and Heretical (2020).

Her novel White Nights, Black Paradise (2015), with a focus on Black women, the Peoples Temple and the Jonestown massacre, was later adapted for the stage. Her novel Rock ’n’ Roll Heretic: The Life and Times of Rory Tharpe (2021) detailed the life of an ex-Pentecostal Black female electric guitarist who at one point says, “Those white boys on the major labels would never give an inch to a Negro woman playing race music.”

Hutchinson founded Black Skeptics Los Angeles (BSLA) in 2010 and is the founder of the Women’s Leadership Project, a high school feminists of color mentoring program in South Los Angeles. She received the Foundation Beyond Belief’s 2015 Humanist Innovator award and the Secular Student Alliance’s 2016 Backbone award. In 2020, the Humanist Chaplaincy at Harvard, a chapter of the American Humanist Association, named her one of its three Humanists of the Year.

BSLA has twice partnered with the Freedom From Religion Foundation by selecting recipients for FFRF’s Forward Freethought Tuition Relief Scholarships. In 2020, four secular students of color each received $5,000 stipends, double the amount of the inaugural awards.

Hutchinson has written and spoken extensively on the particular challenges of “coming out” as an atheist female of color. “[P]atriarchy entitles men to reject organized religion with few implications for their gender-defined roles as family breadwinners or purveyors of cultural values to children. Men simply have greater cultural license to come out as atheists or agnostics.” (Feminism: Opposing Viewpoints, April 1, 2012)

She has been married to Stephen Kelley as of this writing in 2023 for 17 years and has a nonbinary daughter, Jasmine Hutchinson Kelley. She’s a distance runner, acoustic guitarist and rock music enthusiast whose favorites include the Beatles, Neil Young, Sonic Youth, Parliament/Funkadelic, Hendrix/Band of Gypsys, Malina Moye, Brittany Howard, David Bowie and Bob Dylan.

“The white fundamentalist Christian stranglehold on Southern and Midwestern legislatures has proven to be a national cancer that further exposes the dangerous lie of a God-based, biblical morality.”

— Hutchinson, commenting on restrictive abortion bills, The Humanist magazine (July/August 2019)

Judy Blume

On this date in 1938, author Judith Blume (née Sussman) was born in Elizabeth, N.J., the daughter of homemaker Esther (Rosenfeld) and dentist Rudolph Sussman. Blume has described her home as culturally Jewish rather than religious. Her father had six brothers and sisters, almost all of whom died while she was young, so “a lot of my philosophy came from growing up in a family that was always sitting Shiva.” (Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women)

When she was in third grade, she moved with her mother and her older brother David to Miami Beach in hopes the climate would help David recuperate from a kidney infection. Her father stayed in New Jersey. It was then Blume’s “personal relationship” with God started because she thought it was up to her to protect her father.

“I had to keep him safe. I had to keep him well — a terrible burden, you know, for a 9-year-old kid — or 8, really, when I left. And so I would make all kinds of bargains with God. And I had little prayers that I repeated a certain number of times a day. And I hung on to it for a while.” (NPR “Fresh Air,” April 24, 2023)

She was an introspective girl who loved to read. Asked as an adult which of her books was most autobiographical, she said it was Starring Sally J. Freedman as Herself (1977). “Sally is the kind of girl I was at ten. Curious and imaginative, but also a worrier.” (judyblume.com)

After graduating from an all-girls high school, she earned a B.A. in education from New York University in 1960. In 1959 her father had died and she married John Blume, an attorney. Their daughter Randy was born in 1961 and son Lawrence in 1963. After their divorce in 1975, she married Thomas Kitchens, a physicist. They moved to New Mexico for his work and divorced in 1978. In 1987 she married George Cooper, an attorney and nonfiction writer, and as of this writing in 2023 they live in Key West, Fla., and operate a bookstore. Both survived cancer. It’s tough to beat pancreatic cancer but he did, and Blume had a mastectomy in 2012 due to breast cancer.

Blume had started writing after her children were in nursery school but collected a lot of rejection slips until 1969 when her picture book The One in the Middle Is the Green Kangaroo was published. It was the start of something big. As of 2023, her 29 books, all but four for children and teens, have sold more than 90 million copies in 39 languages.

The best-seller success of Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret (1970) was a turning point for Blume. “She acknowledges that it was the first book she gave herself permission to write from her own experience, and it was then that she began to grow ‘as a writer and as a woman.’ ” (Ibid., Shalvi/Hyman) Margaret has a Christian mother and a Jewish father, asks God to help her choose a religion and prays at age 11 to experience puberty. The story closes with her stuffing her bra with cotton balls. Abby Ryder Fortson played the title character in the 2023 film adaptation directed by Kelly Fremon Craig.

Blume said she “was kind of angry at organized religion there for a while, and I wanted it to be different. … [W]e tried joining a synagogue and sending the kids to Sunday school. It didn’t work for me. I just felt they were learning things that I didn’t like, and they were not bat and bar mitzvahed. (Ibid., “Fresh Air”)

Some of her books for young adults were controversial because of the topics she tackled such as family conflict, gender, sexuality, bullying, body image and normal bodily functions. The novel Forever (1975) was frequently banned for its portrayal of teen sex. Are You There God? and others have also been removed from library shelves after religious conservatives complained.

Her work regularly appears on lists of “most frequently challenged authors.” She has served as a spokesperson for the National Coalition against Censorship. The documentary “Judy Blume Forever” directed by Davina Pardo and Leah Wolchok premiered at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival and was released on Prime Video in April 2023.

She was the subject of the Proust Questionnaire in the May 2023 Vanity Fair. Asked how she would like to die, Blume said: “Okay, if I have enough time I might go to Switzerland and drink the drink. I believe in euthanasia. What we do for our beloved pets, we should be able to do for our beloved humans or ourselves.”

Her heroes? “The surgeon, oncologists, and nurses who were there for George and saved his life.”

PHOTO: Blume in 2009; Carl Lender photo under CC 2.0.

TERRY GROSS: What were your children being taught in Sunday school that you didn’t approve of?

BLUME: “I didn’t like how much we are the chosen people, and we are different, and we are better. I didn’t like that.”— National Public Radio "Fresh Air" (April 24, 2023)

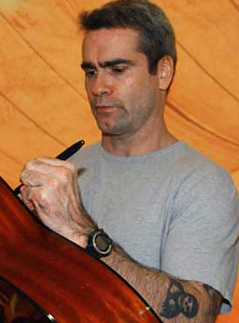

Henry Rollins

On this date in 1961, Henry Rollins (né Henry Lawrence Garfield) was born in Washington, D.C. After high school, Rollins worked on the crew of several D.C. punk bands including Teen Idles. He sometimes filled in for absent lead singers. By 1980, talk of his vocal ability had spread around the D.C. punk rock scene. Rollins became the lead vocalist and lyricist of a band called State of Alert. He was promoted to manager of an ice cream store in Georgetown, which he used to fund his musical hobby.

Rollins became a huge fan of the punk band Black Flag, exchanging letters with its bassist and attending as many concerts as he could and even putting the band up in his parents’ home during an East Coast tour. The band was won over by Rollins’ vocal talent and stage presence. He joined Black Flag as its new frontman and lead singer, quit his manager position, changed his name from Garfield to Rollins and moved to Los Angeles.

Black Flag disbanded in 1986, but Rollins was already touring successfully as a solo artist. He released three solo albums in 1987: Hot Animal Machine, with guitarist Chris Haskett, Drive by Shooting and Big Ugly Mouth. In that same year, Rollins assembled an alternative hard rock group called Rollins Band, active until 2003. Their first chart-topping album was The End of Silence (1992). In 2000, Rollins Band was 47 on VH1’s list of 100 Greatest Artists of Hard Rock. Rollins won a Grammy Award in 1995 for Best Spoken Word Album for Get in the Van: On the Road with Black Flag, a recording of Rollins reading his memoir of the same title.

Rollins has appeared on numerous television series, including MTV’s “Oddville,” (1997), “Batman Beyond” (2001), “The Henry Rollins Show” (2006-2007) and “Sons of Anarchy” (2009). He has authored several books, including a trilogy based on his travels called Black Coffee Blues (1992). He has also appeared in over a dozen films, including “Heat” (1995) with Al Pacino, “Lost Highway” (1997) with Bill Pullman, “Jackass The Movie” (2002) and “Jackass The Movie Two” (2006). Rollins is an activist for gay and human rights. An outspoken war critic, he is strongly supportive of troops.

Rollins said on SIRIUS XM radio: “I’m sure there’s gay people who are Catholics. How do they reconcile that? How do they reconcile that somewhere in the paperwork their religion doesn’t like them?” (“Ron & Fez on The Virus,” video, date unknown). On the same show, Rollins reacted to the expulsion of the child of two lesbians from a Catholic preschool: “When you encounter that kind of hatred, leave. … I was happy that the kid got expelled because maybe the kid has a chance now. They can be put into a place without discrimination, that doesn’t eventually make part of the curriculum to exclude people, like homosexuals.”

Rollins occasionally used “The Henry Rollins Show” to passionately critique religion: “Christian fundamentalists see their fingers being pulled off the steering wheel as their oppressive shackles are more and more being seen as fear-based nonsense” (video, date unknown). Friends with actor William Shatner, he contributed to the mostly secular “Shatner Claus: The Christmas Album” in 2018.

PHOTO: Rollins signing an airman’s guitar during a 2003 USO tour in Iraq.

“In the theory of evolution there is no talk of God and no Bibles are used. They’re not looking for higher powers, extraterrestrials, or anything else that could be found in the science fiction section, because they are not dealing with fiction.”

— Henry Rollins, on an episode of "The Henry Rollins Show” (date unknown)

Simon Pegg

On this date in 1970, actor, screenwriter, comedian and author Simon John Pegg (né Beckingham) was born to parents Gillian Rosemary (née Smith), a civil servant, and John Henry Beckingham, a jazz musician, in Brockworth, England. Following his parents’ divorce when he was seven, Pegg adopted his stepfather’s surname.

Showing a penchant for comedy at a young age, Pegg was the drummer of a band called “God’s Third Leg” when he was 16. Pegg studied English literature and performance studies at Stratford-upon-Avon College, later graduating from Bristol University in 1991 with a bachelor’s degree in theater, film and television.

Moving to London, Pegg pursued a career in standup comedy, which soon led to television opportunities. He emerged into the spotlight after co-writing and co-starring in the sitcom “Spaced” (1999-2001), for which he won a British Comedy Award. For the show, Pegg worked with writer and director Edgar Wright and co-star Nick Frost, who also happened to be his best friend and flatmate. Following the success of the show, Pegg continued to work with them, creating his most lauded films in the Three Flavours Cornetto Trilogy — “Shaun of the Dead” (2004), “Hot Fuzz” (2007) and “The World’s End” (2013).

Pegg’s other major roles include parts in “Doctor Who” (2005), “Mission: Impossible III” (2006), “Run Fatboy Run” (2007), “How to Lose Friends and Alienate People” (2008), “Star Trek” (2009), “Mission: Impossible: Ghost Protocol” (2011), “Paul” (2011) and “Star Trek into Darkness” (2013). Pegg has also done voice parts for “Ice Age: Dawn of the Dinosaurs” (2009), “The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader” (2010) and “The Adventures of Tintin” (2011).

Pegg married Maureen McCann in 2005 and they have one child.

“As an atheist, I’d skip the prayer and go straight to the colonel, who is arguably the god of affordable, bucket housed fried chicken bits.”

— Pegg, from his Twitter account (Nov. 18, 2010)

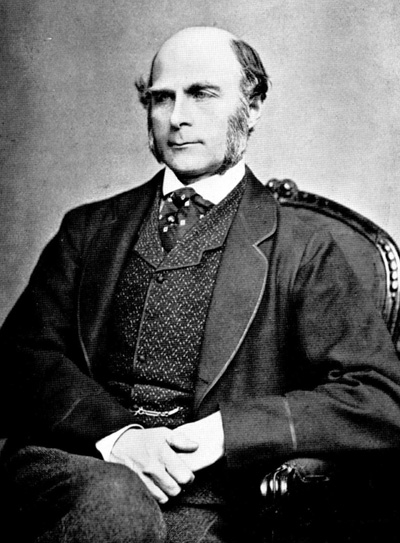

Sir Francis Galton

On this date in 1822, Sir Francis Galton was born in Birmingham, England. The grandson of Erasmus Darwin and cousin of Charles, he was educated in mathematics at Cambridge. An inheritance in 1844 left him free to travel widely. He became a famous explorer, writing several books about his travels in Syria, Egypt and southwest Africa.

In 1863 he became general secretary of the British Association and published a book on weather mapping. His Hereditary Genius was published in 1865. Galton coined the term “eugenics,” defining it very differently from its current meaning. Galton founded a eugenics research fellowship and chair at University College. He also coined the term “nature versus nurture.” His study “Statistical Inquiries into the Efficacy of Prayer” was published in the Aug. 1, 1872, issue of Fortnightly View.

Galton charmingly showed how royalty, the most-prayed-for people in the world, “are literally the shortest lived” of the affluent. Galton observed: “It is a common week-day opinion of the world that praying people are not practical.” He made scholarly contributions to fields as diverse as fingerprinting and psychology. (D. 1911)

“Your book drove away the constraint of my old superstition, as if it had been a nightmare.”

— Galton letter to Charles Darwin, recorded in "Life and Letters of F. Galton" (1914)

Octave Mirbeau

On this date in 1848, French playwright and novelist Octave Mirbeau was born in Paris. He was expelled from a Jesuit college at age 15. Mirbeau adopted strong anarchist views and a fondness for art and art criticism. He ghost-wrote at least 10 novels and many under his own name, including Le Calvaire (Calvary, 1886), Le Journal d’une femme de chambre (Diary of a Chambermaid, 1900) and Dingo (1913). In his 1888 novel, L’Abbé Jules, Mirbeau’s main character is a priest who rebels against Catholicism. The novel explores the repressive and abusive role religion plays in human life.

Sébastien Roch, published in 1890, recounts the sexual abuse of a 13-year-old boy by priests that results in the boy’s expulsion from school and the subsequent destruction of his life. Mirbeau’s plays included “Les Mauvais bergers” (The Bad Shepherds, 1897), the acclaimed “Les affaires sont les affaires” (Business is Business, 1904) and “Le Foyer” (Charity, 1908), a comedy accusing the Catholic Church of exploiting young girls. Mirbeau and French actress Alice Regnault wed in London in 1887. Mirbeau is buried in Paris. D. 1917.

“The universe appears to me like an immense, inexorable torture-garden. … Passions, greed, hatred, and lies; social institutions, justice, love, glory, heroism, and religion: these are its monstrous flowers and its hideous instruments of eternal human suffering.”

— from Mirbeau's novel "Le Jardin des supplices" (The Torture Garden), 1899

Natalie Angier

On this date in 1958, Natalie Angier, Pulitzer Prize-winning science columnist for The New York Times, was born in New York City to a Jewish mother and a father with a Christian Science background. She attended the University of Michigan for two years, then transferred to Barnard College, where she studied English, physics and astronomy and graduated with high honors.