October 21

Carl Brandes

On this date in 1847, Danish writer and politician Carl Edvard Cohen Brandes was born in Copenhagen. He received a Ph.D. from Copenhagen University in Oriental languages and edited several radical political publications. His novels and plays propounded rationalist and progressive ideals.

Brandes notably refused as a freethinker to take the oath when elected to the Folketing (the unicameral parliament) in 1880. Despite attempts to unseat him, he won the right to affirm. Even with his openly atheist views, he was appointed minister to France. His brothers, Georg and Ernst, were also freethinkers. (D. 1931)

© Freedom From Religion Foundation. All rights reserved.“He published translations from Sanskrit and also Danish versions of Isaiah (1902), Psalms (1905), Job, and Ecclesiastes (1907). However, he openly professed atheism and had no connection with Jewish affairs.”

— Encyclopedia Judaica entry on Brandes (1971)

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

On this date in 1772, the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge was born in Devonshire, England, the youngest son of a vicar. As a youngster he was sent to a Christian boarding school in London after his father’s death. He attended Jesus College at the University of Cambridge, which he left without a degree but after having become sympathetic to Unitarianism. He dallied briefly with establishing a utopian society with poet Robert Southy to be called a “pantisocracy.”

His book Poems on Various Subjects was published in 1796. Coleridge collaborated on a volume of poetry with William Wordsworth, Lyrical Ballads in 1798. It contains his most well-known poem, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”: “Water, water, every where / And all the boards did shrink / Water, water, every where / Nor any drop to drink.” In the late 1790s, Coleridge, afflicted with many medical problems, apparently became addicted to opium, to which no social stigma was then attached. His poem “Kubla Khan” and narrative poem “Christabel” were composed during this period.

Coleridge became interested in Kant’s transcendentalism, studied German and translated Friedrich Schiller. He traveled to warmer climes in hopes of improving his health, taking a civil service job on Malta for a time. He lectured periodically in England for more than a decade, reviving the public’s interest in Shakespeare. He continued to write, including Biographia Literaria (1817), Aids to Reflection (1825) and Church and State (1830).

Despite his kind words for atheists (see quote below), Coleridge was probably a mild form of Deistic Unitarian. “Whenever philosophy has taken into its plan religion, it has ended in skepticism; and whenever religion excludes philosophy, or the spirit of free inquiry, it leads to willful blindness and superstition.” (Cited in Allsop’s Letters: Conversations With Recollections of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 1836) D. 1834

© Freedom From Religion Foundation. All rights reserved.“Not one man in ten thousand has goodness of heart or strength of mind to be an atheist.”

— Coleridge, letter to Thomas Allsop, c. 1820

Martin Gardner

On this date in 1914, Martin Gardner was born in Tulsa, Okla. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from the University of Chicago in 1936. After Navy service during WWII, he worked as a reporter for the Tulsa Tribune. His “Mathematical Games” column for Scientific American, originally called “Soma Cube,” ran from 1956-86 and popularized recreational mathematics in the U.S.

Among the more than 100 books and booklets Gardner published are Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science, On the Wild Side, his collected Skeptical Inquirer columns, The New Age, Notes of a Fringe Watcher (1991) and The Healing Revelation of Mary Baker Eddy (1993), which exposed her plagiarism. Gardner called his 1999 work The Whys of a Philosophical Scrivener the book he liked best, calling it “a detailed account of everything I believe.”

He called himself a “philosophical theist,” rejecting all supernaturalism and established religion but embracing the idea of a personal god and an afterlife. (Spectrum magazine, Oct. 17, 2008.) He also called himself a “fideist,” which describes the position that faith supersedes reason, i.e., when someone chooses to believe in a god or gods because it’s comforting, not because there’s evidence. It’s a proposition that is many centuries old among philosophers.

In a December 1995 Scientific American article, Gardner said, “I grew up believing that the Bible was a revelation straight from God. … It lasted about halfway through my years at the University of Chicago.” He retired in 1979 and moved with his wife Charlotte to Hendersonville, N.C., but continued to write math articles and revise some of his older books. After Charlotte died in 2000 he moved to Norman, Okla., where his son James was an education professor. He died there at age 95. (D. 2010)

© Freedom From Religion Foundation. All rights reserved.“[B]ad science contributes to the steady dumbing down of our nation. Crude beliefs get transmitted to political leaders and the result is considerable damage to society. We see this happening now in the rapid rise of the religious right and how it has taken over large segments of the Republican Party. I think fundamentalist and Pentecostalist Pat Robertson is a far greater menace to America than, say, Jesse Helms who will soon be gone and forgotten.”

— Gardner interview, Skeptical Inquirer (March/April 1998)

Ursula K. Le Guin

On this date in 1929, author and iconoclast Ursula K. Le Guin (née Kroeber) was born in Berkeley, Calif. Her parents were the anthropologist Alfred Kroeber and the writer Theodora Kroeber. She graduated from Radcliffe College Phi Beta Kappa in 1951, earned her master’s at Columbia University in 1952 and became a Fulbright Scholar in 1953, the year she met historian Charles Le Guin aboard the Queen Mary. They had three children and lived in Oregon.

Le Guin was a lecturer or writer-in-residence at a number of universities and colleges. She wrote 20 novels and was best known for her pioneering science fiction and fantasy. She also wrote six volumes of poetry, 13 books for children, four collections of essays and many short stories.

Her many literary honors and awards included the Hugo for her 1969 gender-bending book The Left Hand of Darkness and another Hugo in 1975 for The Dispossessed, a utopian fiction. Le Guin, who said in the 1969 introduction to The Left Hand of Darkness, “I am an atheist,” accepted an Emperor Has No Clothes Award from FFRF in 2009. Read her speech here. She died at age 88 at home in Portland, Ore. (D. 2018)

PHOTO: Hajor photo (cropped) CC 1.0: Le Guin at a book signing in Albuquerque in 2013.

“Let the tailors of the garments of God sit in their tailor shops and stitch away, but let them stay there in their temples, out of government, out of the schools. And we who live among real people — real, badly dressed people, people wearing rags, people wearing army uniforms, people sleeping on our streets without a blanket to cover them — let us have true charity: Let us look to our people, and work to clothe them better.”

— Le Guin, acceptance speech after receiving FFRF’s Emperor Award in Seattle (Nov. 7, 2009)

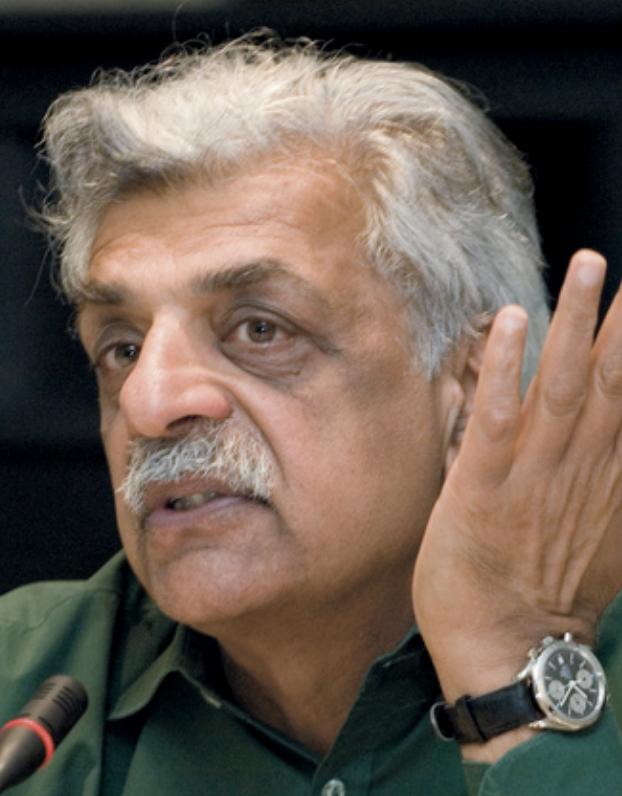

Tariq Ali

On this date in 1943, scholar and author Tariq Ali was born in Lahore, a city then part of British India, and now in Pakistan. A self-described lifelong atheist, Ali was raised in an intellectually activist family where independent thought was encouraged. His parents were Mazhar Ali Khan, a journalist, and Tahira Mazhar Ali Khan, activist and daughter of Sir Sikandar Hyat Khan, who in 1937 became chief minister of the Punjab, a region bordering India and Pakistan.

Ali became politically involved at a young age, organizing demonstrations against Pakistan’s military dictatorship, while studying at the Punjab University. “We grew up in Lahore, which had been one of the most cosmopolitan towns in India. Then you had the partition of India, and you had massive killlings. This is not much talked about these days, but nearly two million people died, as Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs slaughtered each other to create this state.,” he said in 2003.

Finishing his university education at Exeter College at Oxford, Ali studied philosophy, politics and economics. Elected president of the Oxford Union debating club during the Vietnam War, he debated Henry Kissinger. More and more critical of American/Israeli foreign policies, Ali eventually became the voice of criticism against American foreign policy around the world, not the least of which has been his criticism of American policy in Pakistan.

An active voice for the New Left Review for the past 40 years, Ali is a vocal and prolific personage, writing political satires as well as political historical works, historical fiction, nonfiction and political essays. He owned his own independent television production company and has been a regular broadcaster for BBC Radio. His lengthy bibliography, spanning from 1970 to the present, includes Conversations With Edward Said (2005), which he edited, Rough Music: Blair, Bombs, Baghdad, London, Terror (2005), Speaking of Empire and Resistance (2005), and a previously censored screenplay about the last days of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, titled “The Leopard and The Fox,” originally written in 1985, which, in October 2007, was adapted and staged as a play.

Ali lives in London with his longtime partner Susan Watkins, editor of the New Left Review. He has three children.

PHOTO: Ali in 2010. CC 2.0 photo.

“How often in our house had I heard talk of superstitious idiots, often relatives, who hated a Satan they never knew and worshipped a God they didn’t have the brains to doubt?” (Ali, “Clash of Fundamentalisms: Crusades, Jihads and Modernity,” 2002)

“I grew up an atheist. I make no secret of it. It was acceptable. In fact, when I think back, none of my friends were believers. None of them were religious. Maybe a few were believers but very few were religious in temperament.” (“Islam, Empire, and the Left: Conversation With Tariq Ali,” UC-Berkeley, May 8, 2003)

—

Mary Ann Masterton

On this date in 1925, freethinking homemaker and community volunteer Mary Ann Masterton was born in Milwaukee to Rusk and Marion (Duchac) Potter. She graduated from Washington High School in Milwaukee and in 1948 married Bruce Masterton.

The family moved frequently, including three years in Munich, Germany, due mainly to Bruce’s work as a buyer for the Army & Air Force Exchange Service, which supplies military PX facilities worldwide. Mary Ann kept the home fires burning for their four children — cooking, cleaning, gardening and sewing clothes — while volunteering prolifically at schools, Lighthouse for the Blind, Scottish Rite Hospital and soup kitchens.

She made audio tapes for the visually impaired and taught English as a second language and youth classes at Unitarian Universalist congregations. Her UU connection was deep and extended over 50 years, said her daughter Samantha: “The Unitarian church in Dallas I was brought up in was almost militant about their common atheism. It seemed to be an unofficial requirement to join.”

People were drawn to her, Samantha said. “She was a stay-at-home mom to us, wife to her husband, and friend to everyone she met. She loved freely and fervently. Everyone felt they had a special connection to her. She loved putting on shows, singing, making people laugh.”

Mary Ann and Bruce moved in 1983 to Antigo, Wis., to care for her mother, who died two weeks later. She continued her community connections there with the Unitarians, Friends of the Library, schools and other groups. Bruce died in 1993.

While teaching education classes at her UU congregration, she wrote this in the parish newsletter: “I have lately come to realize that in order to be an honest person, so people can know and accept and (I hope) love who I really am, I must ‘come out’ as an atheist. For over 73 years I have considered myself so, but I hesitated to come out for fear of being misunderstood, of being shunned, and of losing friends and family.

She continued, “But having witnessed the healthy social changes LGBTQ people have developed by coming out to the world, I feel atheists should do the same for ourselves, for other atheists who have remained silent and unsupported, for the mental and emotional growth of all. Let us help the world to be a better place by teaching that atheists are searching and serving and singing of a broader concept of life and morals and death. When atheists speak out on our truths, we will find there are more of us than we knew. So, atheists: Speak up! Identify yourselves! Come out! We live honest, wonderful lives that include the best hopes religions offer without any gods or myths.”

“Her Christian friends insisted that Mom was a believer because she’d always let them pray for her because she thought it couldn’t hurt. But she didn’t believe any of it,” her daughter said after Mary Ann died at home at age 92. A private family gathering was held to mark her passing and memorials were established to benefit literacy and Antigo public schools. (D. 2018)

PHOTO: Masterton protesting GOP union-busting at the Wisconsin Capitol in her mid-80s. (Leslie Amsterdam photo, cropped)

I PRAISE ROUND STONES

I praise no god.

I only praise the sun and wind and

Moon-lit babies kissing gentle in my arms

Remembering other arms

And other kissing nights.

Books and letters I praise

And small fires that warm my face

And light the page.Cozy rooms in many houses

Filled with laughter and good talk –

These I praise.

And quiet walks

And fresh baked bread dripping honey.

I praise all the tender hands that soothe

And hold – make music – mend.I praise dear friends and lovers.

And, oh, the magic gardens burning

Their bright colors deep into my heart

Turning my bones into embers that will

Glow forever.

I praise round stones.

No god I praise.Whatever raises me to life

— Mary Ann Masterton verse, November 1983

Puts me on my knees to praise.

To praise

Amen.