January 8

Lewis Lapham

On this date in 1935, Lewis Henry Lapham was born in San Francisco. He earned his bachelor’s degree in history from Yale University in 1956 and attended Cambridge University (1956–57). After graduation he worked as a reporter for the San Francisco Examiner (1957-60) and at age 25 became the U.N. correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune (1960-62). He later became managing editor of the prominent literary journal Harper’s Magazine (1971-75) and was soon appointed its editor (1976-2006).

He was a prolific journalist who wrote articles for many publications, including The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. In 2007, Lapham founded and became editor of Lapham’s Quarterly, a history magazine. His many books included Waiting for the Barbarians (1998) and Gag Rule: On the Suppression of Dissent and the Stifling of Democracy (2005).

Lapham was also the host of the television show “Bookmark” (1988-91). He received the 1994 and 1995 National Magazine Awards for his journalistic contributions to Harper’s. In 2007, Lapham was included in the American Society of Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame. He married Joan Brooke Reaves in 1972 and they had three children: Anthony, Elizabeth and Winston. Andrew married the daughter of former Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney.

“As an unbaptized child raised in a family unaffiliated with the teachings of a church, I missed the explanation as to why the stories about Moses and Jesus were to be taken as true while those about Apollo and Rumpelstiltskin were not,” Lapham wrote of his lifelong nonbelief in “Mandates of Heaven,” the introduction to the Winter 2010 issue of Laphams Quarterly.

He continued: “[French philosopher Michel] Onfray observes that ‘a fiction does not die, an illusion never passes away,’ situating Yahwey, together with Ulysses, Allah, Lancelot of the Lake, and Gitche Manitou, among the immortals sustained on the life-support systems of poetry and the high approval ratings awarded to magicians pulling rabbits out of hats.”

He expressed his disdain for the intersection of church and state in America, saying, “The dominant trait in the national character is the longing for transcendence and the belief in what isn’t there — the promise of the sweet hereafter that sells subprime mortgages in Florida and corporate skyboxes in heaven.” He died in Rome at age 89. (D. 2024)

PHOTO: By Terry Ballard under CC 2.0.

"God is the greatest of man's inventions, and we are an inventive people, shaping the tools that in turn shape us, and we have at hand the technology to tell a new story congruent with the picture of the earth as seen from space instead of the one drawn on the maps available to the prophets wandering the roads of the early Roman Empire."

— Lewis Lapham, Lapham's Quarterly (Winter 2010)

David Bowie

On this date in 1947, music legend David Bowie was born David Robert Jones in London to Margaret Mary, a waitress, and Haywood Stenton Jones, a promotions officer. He was raised without religion. Though he dabbled in different religions throughout his life, he later described himself as a nonbeliever.

His interest in music was piqued when his father brought home 45s of early American rock and roll artists, including Elvis Presley, Fats Domino and Little Richard. He was also influenced by an older brother, Terry, who tragically committed suicide when Bowie was 38. He joined his first band at 15 and hopped from band to band until he found success as a solo performer in 1969 with the release of his album “Space Oddity.”

His career was marked by experimentation with genre and persona, although he was most frequently considered a glam rock artist. He’s famous for his alter ego Ziggy Stardust, a character from Mars who was Bowie’s own creative invention. Throughout the 1970s and ’80s, he continued to release hit singles, including “Star Man,” “Young Americans,” and “Changes.” He collaborated with British rock group Queen on the song “Under Pressure” in 1981, which reached the top of the charts in the UK.

Bowie married Angela Barnett, a model and actress born in Cyprus, in 1970. They had a son, Duncan, before divorcing in 1980. He married the supermodel Iman in 1992. Their daughter Alexandra was born in 2000. Bowie didn’t perform live after 2006 but continued to record music. He died in New York City of liver cancer, two days after turning 69. (D. 2016)

PHOTO: Bowie at the Metropolitan Opera opening night in New York City in 2006; photo by NYCArthur under CC 2.0.

“I'm not quite an atheist and it worries me. There's that little bit that holds on: Well, I'm almost an atheist. Give me a couple of months.”

— Bowie, interview with beliefnet.com (June 2003)

Sarah Polley

On this date in 1979, actress and filmmaker Sarah Ellen Polley was born in Toronto, Canada, to Diane (née MacMillan) and Michael Polley. Her British father and her mother both had acting backgrounds. She would learn as an adult that her biological father was actually film producer Harry Gulkin, with whom her mother had had an affair. (“Stories We Tell” documentary, 2012)

Her mother had died of cancer when Polley was 11. Her home life started a downward spiral, moving from an “incredibly boisterous place, with music playing all the time, and political discussions, and books being discussed, and laughter” to life with a depressed dad in which she was basically left to her own devices and stopped going to school. By age 15, she had lived with her brother’s ex-girlfriend, her first boyfriend and then alone. (The New Yorker, March 13, 2022)

“[The Ontario Coalition Against Poverty] took me in when I was 15, living on my own, with no community. They gave me a political education and a place to belong. It’s why, to this day, I don’t understand why many progressives are so focused on being ‘civil’ and ‘polite’ about the war on the poor,” she later wrote. (Twitter, Nov. 27, 2020)

Asked as an adult how she got into acting, Polley said that as a child of about age 5 or 6, she and her older siblings (she was the youngest) were surrounded by it. “My dad had been an actor — he wasn’t when I was a kid, he was working at an insurance company to support the family — and my mom was a casting director and produced comedy shows.” (Ibid., The New Yorker)

Her first credited movie role was in Disney’s “One Magic Christmas” (1985), starring Harry Dean Stanton and Mary Steenburgen and filmed in Ontario. Her first major role was at age 8 as Ramona Quimby in the Canadian TV series “Ramona” (1988), based on Beverly Cleary’s books. It aired for one season before going to video. Her role in the popular series “Road to Avonlea” (1990-96) made her financially independent and she was dubbed “Canada’s Sweetheart” by some in the press.

“Avonlea” was picked up by the Disney Channel for U.S. distribution. At age 12 she attended an awards ceremony while wearing a peace sign to protest the first Gulf War. Disney executives asked her to remove it but she refused, not a decision the company liked.

“The Sweet Hereafter” (1997), in which she sang three songs and co-wrote the title track, brought her to the attention of more of the public outside Canada. Subsequent roles of note included “Go” (1999), “My Life Without Me” (2003), a remake of “Dawn of the Dead” (2004) and “The Secret Life of Words,” opposite Tim Robbins and Julie Christie, for which she was nominated as Best European Actress by the European Film Academy.

Polley made her feature film directorial debut with “Away From Her” (2006), for which she won the Canadian Screen Award for Best Director and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. In 2017 she wrote the six-part miniseries “Alias Grace,” based on the 1996 novel of the same name by her longtime friend Margaret Atwood, which Polley had started adapting in 2012.

She was married to film editor David Wharnsby from 2003-08. She married David Sandomierski in 2011. He went on to become a law school professor at Western University in London, Ontario. They have three children together. She suffered a debilitating concussion in 2016 when struck on the head by a fire extinguisher hung over a lost-and-found box at her pool and community center. It would seriously affect her ability to work for over four years.

“Women Talking,” written and directed by Polley, had its world premiere at the Telluride Film Festival in September 2022. It’s based on Miriam Toews’ 2018 novel about several Mennonite women who come to realize they have all been drugged and raped by men in their community.

Polley admires directors Ingmar Bergman and Terrence Malick, saying that Malick’s “The Thin Red Line” (1998) “single-handedly brought me out of a deep depression. It shifted something in me. I’m an atheist, but it was the first time that it gave me faith in other people’s faith.” (Toronto Life magazine, October 2006)

PHOTO: Polley at the 2009 Venice Film Festival; Nicolas Genin photo under CC 2.0.

“I don’t have faith in anything but my fellow human beings and the world around me. I have strong faith in people, but not beyond people. The world is a beautiful place, it’s a beautiful enough place for me to worship and have faith in and — it’s enough for me.”

— Polley, quoted in "She Should Talk: Conversations With Exceptional Young Women About Life, Dreams & Success" by Erica Ehm (1994)

Butterfly McQueen

On this day in 1911, Thelma “Butterfly” McQueen was born in Tampa, Fla. She was best known for her role as Prissy in the 1939 MGM movie “Gone with the Wind.” Butterfly, which she changed her legal name to, was a lifelong atheist except for her childhood religious indoctrination.

The role of Prissy, she would later say, “was not a pleasant part to play — I didn’t want to be that little slave. But I did my best, my very best.” She quit movie acting in 1947 to avoid further typecasting, going to work as a real-life maid, Macy’s sales lady and seamstress.

She earned her bachelor’s degree in political science in 1974 at age 64 from the New York City College. McQueen became FFRF’s premiere Freethought Heroine recipient (see that for more interesting biographical details) in 1989 and was an FFRF Life Member. She died in Augusta, Ga., at age 84 from burns sustained when a kerosene heater she was lighting malfunctioned and burst into flames. (D. 1995)

"As my ancestors are free from slavery, I am free from the slavery of religion."— Butterfly McQueen, Atlanta Journal and Constitution (Oct. 8, 1989)

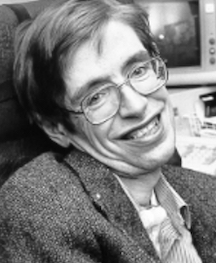

Stephen Hawking

On this date in 1942, cosmologist Stephen Hawking was born in Oxford, England, “300 years after the death of Galileo,” as he once noted. He attended Oxford, studying physics, then earned his Ph.D. in cosmology at Cambridge. By his 21st birthday he had been diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig’s disease).

Despite his disability, which confined him to a wheelchair and forced him to rely on mechanized speech, Hawking became a research fellow, worked at the Institute of Astronomy, and in 1973 joined the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics at Cambridge.

Hawking is celebrated for his work on unifying General Relativity with Quantum Theory. His popular science books include A Brief History of Time, Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays and The Universe in a Nutshell. Although some rationalists have been disappointed in his tendency to use the term “god” too loosely as a metaphor, Hawking made it clear he did not believe in a personal god.

In an interview with Diane Sawyer on ABC News (June 7, 2010), Hawking said, “There is a fundamental difference between religion, which is based on authority, [and] science, which is based on observation and reason. Science will win because it works.”

In his follow-up book The Grand Design (2010), Hawking and co-author Caltech physicist Leonard Mlodinow wrote that “God” is not necessary: “Because there is a law such as gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing. Spontaneous creation is the reason there is something rather than nothing, why the universe exists, why we exist. It is not necessary to invoke God to light the blue touch paper and set the universe going.”

In an interview with the Spanish newspaper El Mundo (Nov. 6, 2015), Hawking was more forthright about declaring his atheism: “Before we understand science, it is natural to believe that God created the universe. But now science offers a more convincing explanation. What I meant by ‘we would know the mind of God’ is, we would know everything that God would know, if there were a God, which there isn’t. I’m an atheist (Soy ateo).”

In his last book, Brief Answers to the Big Questions, published posthumously in 2018, Hawking wrote, “There is no God. No one directs the universe.” Included in his parting advice: “Remember to look up at the stars and not down at your feet. Try to make sense of what you see and wonder about what makes the universe exist. Be curious. And however difficult life may seem, there is always something you can do and succeed at.”

Hawking met Jane Wilde in 1962, the year before his motor neuron diagnosis. They married in 1965 and had three children: Robert (1967), Lucy (1969) and Timothy (1979). His poor health and her strong Christian beliefs led to their divorce in 1995, after which he soon married Elaine Mason, one of his nurses.

After their divorce in 2006, Hawking resumed closer relationships with Jane and his children. Her book Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen was published in 2007 and was made into a film, “The Theory of Everything,” in 2014.

Hawking died at his home in Cambridge at age 76 and his ashes were interred in Westminster Abbey’s nave between the graves of Sir Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin. (D. 2018)

PHOTO: Hawking at NASA’s StarChild Learning Center, c. 1980s

"All that my work has shown is that you don’t have to say that the way the universe began was the personal whim of God."

— Hawking, "Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays" (1993)

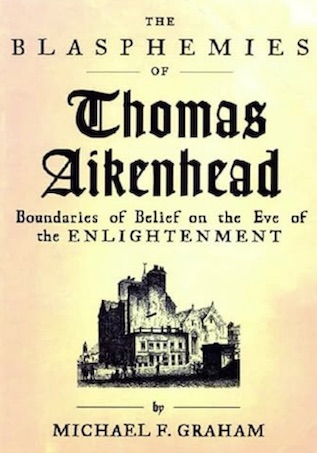

Thomas Aikenhead (Died)

On this day in 1697, Scottish medical student Thomas Aikenhead, age 20, was hanged to death for blasphemy in Britain’s last execution for blasphemy. The Edinburgh student was found guilty of cursing and railing against God, denying the incarnation and the holy trinity and scoffing at the scriptures. He was convicted on the testimony of five “friends” to whom he had confided his strong religious doubts. Evidence against him were “atheistic” books in his possession. The Church of Scotland urged his “vigorous execution.”

"It is a principle innate and co-natural to every man to have an insatiable inclination to the truth, and to seek for it as for hid treasure."

— Aikenhead's letter to friends on the day of his execution

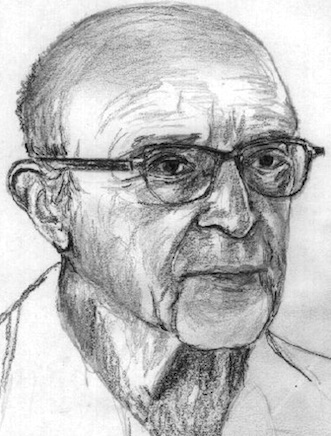

Carl Rogers

On this date in 1902, humanist psychologist Carl Ransom Rogers was born in Oak Park, Ill., one of five children of Walter and Julia Rogers. His conservative Protestant parents created a home filled with prayer and protection for their children from society’s influences. With few outside friends, Rogers led a quiet, sheltered life, reading and studying. Able to read before age 5, he skipped kindergarten and first grade and started school in the second grade.

Enrolling at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Rogers decided to study agriculture. He then changed his major to history and then to religion, intending to become a minister. While on a trip to China for an international Christian conference, Rogers started to doubt his religious convictions, although it took two years in seminary before he left his religious track. Rogers obtained his M.A. in education from Columbia University in 1928 and his Ph.D. in 1931. While working on his doctorate, he was involved in child studies at the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children in Rochester, N.Y., becoming the center’s director.

He began to engage in a new, humanistic approach to psychotherapy and in 1939 wrote his first book, “The Clinical Treatment of the Problem Child. He became a full professor at Ohio State University and, in 1942, wrote a second book, Counseling and Psychotherapy: Newer Concepts in Practice, wherein patients could gain the necessary insight to restructure their own lives in conjunction with an empathetic therapist. The premise of self-help and self-understanding was contrary to prior clinical methodologies, in which the psychologist told the patient what to do.

In 1945 he was asked to begin a new counseling center at the University of Chicago and, in 1951, published his groundbreaking work Client-Centered Therapy. Rogers became president of the American Academy of Psychotherapists in 1956 and a year later returned to UW-Madison to work in the psychology department. After becoming disillusioned with academia, he moved to La Jolla, Calif., in 1964, where he worked on the staff at the Western Behavioral Sciences Institute. In 1964 he was named “Humanist of the Year” by the American Humanist Association. He remained in La Jolla for the rest of his life.

Rogers wrote numerous journal articles and 16 books, the best known being On Becoming a Person (1962). He traveled worldwide to promote his theories in the areas of education, the social sciences and in national social conflict, specifically focusing his efforts on leading encounter groups between people of conflicting political factions.

He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1987 for his work with international intergroup conflict in South Africa and Northern Ireland. He died of a heart attack at age 85 in La Jolla. (D. 1987)

“Experience is, for me, the highest authority. The touchstone of validity is my own experience. … Neither the Bible nor the prophets — neither Freud nor research — neither the revelations of God nor man — can take precedence over my own direct experience.”

— Rogers, "On Becoming a Person" (1961)