reformers

Alice Paul

On this date in 1885, feminist Alice Stokes Paul was born in Moorestown, N.J., to a Quaker family which believed in the equality of the sexes. She attended Swarthmore College, then spent a year as a student at the New York School of Philanthropy while working at a settlement house. Paul earned a master’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania in economics and sociology, then won a fellowship to study in England. She took courses at the University of Birmingham and London School of Economics and worked in the British settlement movement.

Paul was arrested and jailed several times in England for joining in brick-throwing at government buildings and took part in hunger strikes. Returning to New Jersey in 1910, she lectured in favor of adopting the British militancy. That year she stopped speaking to Quaker groups after her views were repudiated by them and transferred her allegiance to pure feminism. Like Quaker-raised Susan B. Anthony, Paul became an agnostic, according to Warren Allen Smith in Who’s Who in Hell. Her story inspired the 2004 HBO film “Iron Jawed Angels” in which she was portrayed by Hilary Swank.

Teaming up with her New York friend Lucy Burns, Paul talked the National American Woman Suffrage Association into letting them take over its congressional committee with help from Jane Addams, in 1912. They set up shop in Washington, D.C., organizing a historic parade of suffragists on March 3, 1913, upstaging the inauguration of President Woodrow Wilson. Peacefully parading women were attacked by a violent mob, which created huge headlines and reinvigorated the suffrage campaign.

During World War I, Paul and supporters picketed the White House with placards asking “How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?” When mobs attacked, police arrested more than 100 suffragists, many of whom were sentenced to notorious workhouses. Paul and other hunger strikers were force-fed, and she was even transferred to a psychiatric hospital. The public outcry forced Wilson to unconditionally release the women. Demonstrations continued and Congress finally enacted the suffrage amendment, ratified by the states in 1920.

Paul went to law school, earning three degrees, then began promoting the Equal Rights Amendment, which she called the Lucretia Mott Amendment. Many women’s groups at the time, including the League of Women Voters and Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, opposed the ERA on the grounds that women needed protective legislation. The amendment was first introduced into Congress in 1923. Paul lobbied for it in every successive session until 1972, when it passed. The combined forces of the tax-exempt religious lobbies defeated the ratification process in 1982 after it failed to gain support in the required number of states.

Paul, who never married, died at age 92 at a Quaker facility in New Jersey, less than a mile from her birthplace. (D. 1977)

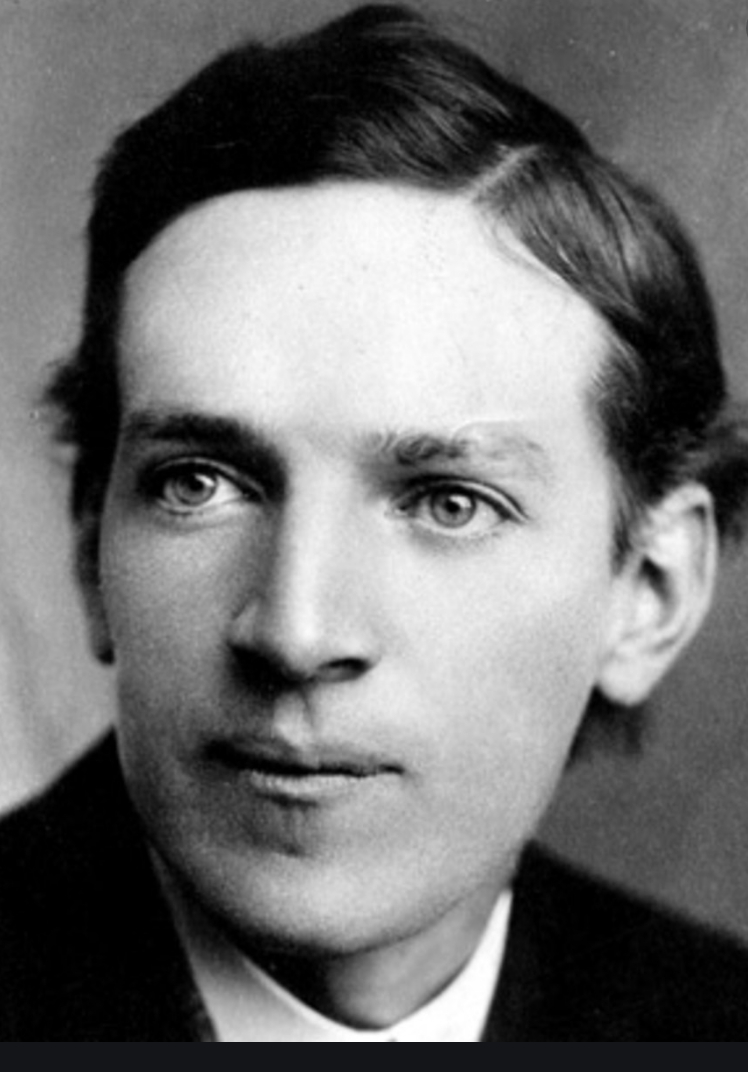

PHOTO: Paul in 1915.

"Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex."

— From the Equal Rights Amendment drafted by Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman

Beatrice Webb

On this date in 1858, Beatrice Webb (née Beatrice Potter) was born in Gloucestershire, England. The eighth of nine sisters, Potter’s mother resented her for not having been born a boy. Like most Victorian girls, Potter received a poor education in spite of her father’s wealthy career as a timber entrepreneur. Unusually though, her father, unlike most Victorian men, believed in the intellectual equality, if not superiority of women. As a teenager, with an increasingly inquisitive mind, Potter read every history, economy and philosophy book within reach and began to rebel against her privileged life.

Herbert Spencer, a close friend of the family, intrigued Potter with his “scientific method,” which she believed could be applied to solve society’s social problems. She was one of the first researchers to argue that poverty has underlying causes instead of being a deserved state. By 1885 her research, including on the English cooperative movement and housing projects for the poor, inspired her to break with capitalism and openly advocate socialism. The success of her research was her fearless commitment to disguise herself as one of her subjects (often poor workers) and immerse herself in their lifestyle.

In 1890 Potter needed historical information for an upcoming book on London sweatshops and was referred to socialist and reformist Sidney Webb. Webb fell in love with her but she rejected his proposals for marriage until it became apparent that they were deeply intellectually compatible. They married in 1892 and wrote their first of many books together, The History of Trade Unionism (1894). Personal friend H.G. Wells once described the Webbs as “the most formidable and distinguished couple conceivable” (Oxford Companion to English Literature, 1995).

The Webbs’ influence on British government is still felt. Beatrice was among the first to conceive of a “national health plan,” the basis for the National Health Service. She also apprenticed with Charles Booth, helping him write the influential study The Life and Labour of the People in London (1902-03). In opposition to Britain’s 1934 Poor Law, the Webbs wrote a minority report which helped lay the foundation of Britain’s social services system.

After joining the Fabian Society in the 1890s, the Webbs socialized with other freethinkers. Along with George Bernard Shaw and Graham Wallas, the Webbs founded The London School of Economics and Political Science in 1895 to train social scientists to promote “the betterment of society.” The Webbs both held government posts throughout their later years. Together, they published around 500 books, articles, pamphlets and edited volumes. They are interred together in the nave of Westminster Abbey. D. 1943.

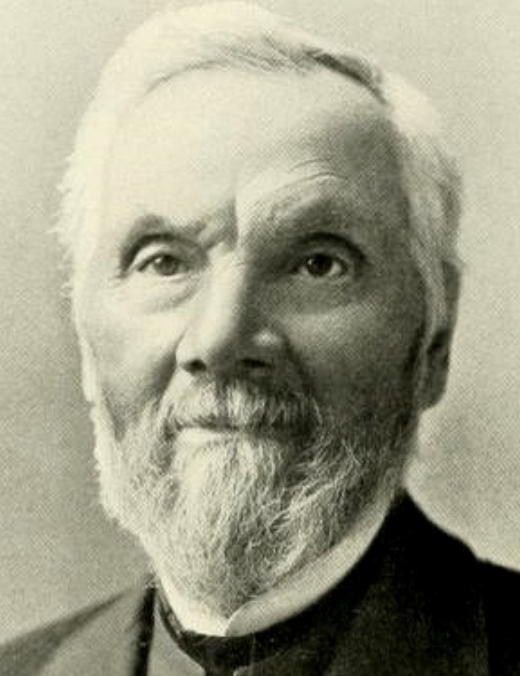

PHOTO: Webb in 1875.

"That part of the Englishman’s nature which has found gratification in religion is now drifting into political life."

— Webb, quoted in "100 Years of Freethought" by David H. Tribe (1967)

John Ruskin

On this date in 1829, art critic and reformer John Ruskin was born an only child in London. His mother, a devout evangelical, wanted him to study for the clergy but he turned to the arts, studying art and poetry at King’s College and Oxford. In Praeterita (1855), Ruskin related that by age 14 he had rejected the literal truth of the scriptures: “It had never entered into my head to doubt a word of the Bible, though I saw well enough already that its words were to be understood otherwise than I had been taught; but the more I believed it, the less it did me any good.”

Ruskin credited his interest in geology with destroying his faith, being unable to reconcile science with such claims as the biblical flood. Ruskin became a public figure when he took up the cudgels to defend the paintings of J.M.W. Turner, writing the book Modern Painters (1843). Ruskin wrote several other books on art, then turned to social reform, working as an art teacher with the London Working Men’s College, and writing on economic questions. Ruskin also founded the Art School at Oxford, a museum in Sheffield, and attempted some experimental agrarian communities. “In an earlier age he might have become a saint,” noted E.T. Cook in the Dictionary of Natural Biology.

Ruskin gave away most of his inheritance on the theory that it was a contradiction to be a rich socialist. He became a professor of art at Oxford (1869-79). His interest in architecture helped to birth the National Trust and the Society of the Protection of Ancient Buildings. In his reforming years (1858-75), Ruskin was decidedly agnostic, telling Augustus Hare in 1860 that he “believed nothing” (Hare, Story of My Life). Although he dallied with spiritualism in the 1870s and regained a vague theism, according to biographer Cook, Ruskin never rejoined the church. Cook also wrote that Ruskin rejected the misconception that morality depends on religion. Ruskin’s returning interest in religion coincided with his first of several recurring bouts of mental illness in 1878. D. 1900.

"It is neither Madonna-worship nor saint-worship, but the evangelical self-worship and hell-worship — gloating, with an imagination as unfounded as it is foul, over the torments of the damned, instead of the glories of the blest — which have in reality degraded the languid powers of Christianity to their present state of shame and reproach."

— Ruskin, "Fors Clavigera" (1875)

Jeremy Bentham

On this date in 1748, Jeremy Bentham was born in London. The great philosopher, utilitarian, humanitarian and atheist began learning Latin at age 4. He earned his B.A. from Oxford by age 15 or 16 and his M.A. at 18. His Rationale of Punishments and Rewards was published in 1775, followed by his groundbreaking utilitarian work Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Bentham propounded his principle of “the greatest happiness of the greatest number.” He worked for political, legal, prison and educational reform.

Inheriting a large fortune from his father in 1792, Bentham was free to spend his remaining life promoting progressive causes. The renowned humanitarian was made a citizen of France by the National Assembly in Paris. In published and unpublished treatises, Bentham extensively critiqued religion, the catechism, the use of religious oaths and the bible. Using the pen name Philip Beauchamp, he co-wrote a freethought treatise, Analysis of the Influence of Natural Religion on the Temporal Happiness of Mankind (1822). D. 1832.

"No power of government ought to be employed in the endeavor to establish any system or article of belief on the subject of religion.”

“[I]n no instance has a system in regard to religion been ever established, but for the purpose, as well as with the effect of its being made an instrument of intimidation, corruption, and delusion, for the support of depredation and oppression in the hands of governments."

— Bentham, "Constitutional Code," "The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham," eds. F. Rosen and J. H. Burns (1983)

Susan B. Anthony

On this date in 1820, Susan Brownell Anthony was born in Massachusetts. She taught school from ages 15 to 30 before devoting her life to reform. She and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, starting in 1850, became lifelong feminist collaborators. The tireless crusader spent 30 years campaigning for women’s suffrage. Raised Quaker, she became a Unitarian but at the end of her life was an agnostic. Anthony’s professed “creed” was that of “the perfect equality of women,” according to Stanton.

While privately scolding Stanton for editing the controversial Woman’s Bible, Anthony publicly defended her: “I think women have just as much a right to interpret and twist the Bible to their own advantage as men always have interpreted and twisted it to theirs.” (Interview in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, quoted in The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony.) She also confessed, “But while I do not consider it my duty to tear to tatters the lingering skeletons of the old superstitions and bigotries, yet I rejoice to see them crumbling on every side.”

Her biographer Ida Husted Harper wrote that after Anthony visited a poor mother of six in Ireland in 1883, Anthony noted that “the evidences were that ‘God’ was about to add a No. 7 to her flock” and later commented, “What a dreadful creature their God must be to keep sending hungry mouths while he withholds the bread to fill them!”

There is no record she ever had a serious romance despite receiving marriage offers and would answer journalists’ questions with statements like “It always happened that the men I wanted were those I could not get, and those who wanted me I wouldn’t have.” To another she answered, “I never found the man who was necessary to my happiness. I was very well as I was.” She had no desire to “give up my life of freedom to become a man’s housekeeper.”

But according to Sted Mays, writing in the Gay & Lesbian Review, Anthony felt compelled to create a conventional public persona and made excuses for her unmarried status in order to hide her same-sex attractions: “She talked in interviews about not wanting to be trapped in a male-dominated relationship. But the real reason she never had a serious relationship with a man was that her passions were directed toward other women.” (“Stop Straightwashing Susan B. Anthony,” Feb. 10, 2020)

She died of heart failure at age 86 at her home in Rochester, N.Y. (D. 1906)

“I could not dash her faith with my doubts, nor could I pretend a faith I had not; so I was silent in the dread presence of death.”

— Anthony contemplating her sister on her deathbed, "The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, Vol. 2" by Ida Husted Harper (1898)

E.B. Foote

On this date in 1829, reformer Edward Bliss Foote was born in Cleveland, Ohio. He was brought up in a conforming Presbyterian household. Foote was a physician with a hand in the newspaper business, publishing the first newspaper in New Britain, Conn. Becoming a Unitarian, then an agnostic, he befriended D.M. Bennett, publisher of The Truth Seeker. Foote was the only foe of the first Comstock bill, which was introduced in the New York legislature in 1872, and passed despite his efforts.

The repressive Comstock Act was soon adopted by Congress, creating censorship of the press through postal regulations. Comstock went after his early foe in 1874, charging Foote with violating postal laws for mailing an educational pamphlet advocating the right of families to limit their size through “contraceptics.” He was fined $3,500 by Judge Benedict of the U.S. Circuit Court of the Southern District of New York in 1876.

Foote helped to organize the National Defense Association seeking repeal of the Comstock laws and aided other Comstock victims. He worked actively within medical societies and at the state legislature to oppose the legitimization of Christian scientists and faith healers. A lifelong advocate of woman’s suffrage, he sent a check of $25 to Susan B. Anthony when she was fined $100 for voting in the 1872 presidential election. He was a member of numerous freethought and professional groups. His son Edward Bond Foote also became a physician and freethinker. (D. 1906)

W.E.B. Du Bois

On this date in 1868, W.E.B. Du Bois (William Edward Burghardt) was born in Great Barrington, Mass. He attended all-black Fisk College in Nashville, then earned his B.A. in 1890 and his M.S. in 1891 from Harvard. Du Bois studied at the University of Berlin on a fellowship. Returning from Europe, he completed his graduate studies in history and in 1895 was the first African-American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard. He taught economics and history at Atlanta University from 1897-1910. The Souls of Black Folk (1903) made his name, in which he urged black Americans to stand up for their educational and economic rights.

Du Bois was a founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and edited the NAACP’s official journal, The Crisis, from 1910-34. He turned The Crisis into the foremost black literary journal. He expanded his interests to global concerns and is called the “father of Pan-Africanism” for organizing international black congresses.

Although he used some religious metaphor and expressions in some of his writing, Du Bois called himself a freethinker (see quote below). In “On Christianity,” a posthumously published essay, Du Bois critiqued the black church: “The theology of the average colored church is basing itself far too much upon ‘Hell and Damnation’ — upon an attempt to scare people into being decent and threatening them with the terrors of death and punishment. We are still trained to believe a good deal that is simply childish in theology. The outward and visible punishment of every wrong deed that men do, the repeated declaration that anything can be gotten by anyone at any time by prayer.”

Du Bois married Nina Gomer, with whom he had two children. As a widower he married Shirley Graham. At age 93, he and his wife traveled to Ghana to take up residence and start work on an encyclopedia of the African diaspora. In early 1963 the U.S. refused to renew his passport because of his Communist Party ties, so he made the symbolic gesture of becoming a citizen of Ghana, where he died two years later in the capital Accra at age 95. (D. 1963)

"My ‘morals’ were sound, even a bit puritanic, but when a hidebound old deacon inveighed against dancing I rebelled. By the time of graduation I was still a ‘believer’ in orthodox religion, but had strong questions which were encouraged at Harvard. In Germany I became a freethinker and when I came to teach at an orthodox Methodist Negro school I was soon regarded with suspicion, especially when I refused to lead the students in public prayer. When I became head of a department at Atlanta, the engagement was held up because again I balked at leading in prayer. … I flatly refused again to join any church or sign any church creed. From my 30th year on I have increasingly regarded the church as an institution which defended such evils as slavery, color caste, exploitation of labor and war. I think the greatest gift of the Soviet Union to modern civilization was the dethronement of the clergy and the refusal to let religion be taught in the public schools."

— W.E.B. Du Bois, "African-American Humanism: An Anthology," edited by Norm R. Allen Jr. (1968)

Henrik Ibsen

On this date in 1828, Henrik Ibsen was born in Norway. The playwright, a social critic who in his later years pioneered realist drama, produced a roster of literary classics. His plays include “Brand” (1866), “Peer Gynt” (1867), “A Doll’s House” (1879), “Enemy of the People” (1882) and “Hedda Gabler” (1890). Reportedly becoming a freethinker as a teenager, Ibsen was later influenced by Georg Brandes, penning “The Emperor and the Galilaean” (1873). Its disillusioned protagonist sets out to overthrow Christianity.

In his play “Ghosts” (1881) he wrote, “It’s not only what we have inherited from our father and mother that walks in us. It’s all sorts of dead ideas, and lifeless old beliefs, and so forth. They have no vitality, but they cling to us all the same, and we can’t get rid of them.” In “The Pillars of Society” (1877) he wrote, “The spirit of truth and the spirit of freedom — these are the pillars of society.”

Ibsen married Suzannah Thoresen when he was 30 and had a son, Sigurd, who as prime minister played a central role in 1905 in the dissolution of the union between Norway and Sweden. He died at home in Oslo at age 78, six years after the first of a series of strokes. (D. 1906)

“The state has its root in Time: it will have its culmination in Time. Greater things than it will fall; all religion will fall. Neither the conceptions of morality nor those of art are eternal. To how much are we really obliged to pin our faith?

— Ibsen letter to Georg Brandes (Sept. 24, 1871)

John Ballance

On this date in 1839, John Ballance was born in County Antrim, Northern Ireland, the first of 11 children. The ironmonger’s apprentice emigrated first to Birmingham, then, with his new wife, to New Zealand.

First elected to the House of Representatives in 1875 on a ticket calling for free education, Ballance later became Minister of Education and Minister of Finance. He was then appointed Native Minister and Minister for Defence and Lands. Ballance founded his country’s Liberal Party. In 1891, Ballance was elected the 14th Prime Minister of New Zealand as a Liberal.

“He took his politics from his liberal mother, who had a Quaker upbringing, rather than his conservative Church of Ireland father. Ultimately, Ballance rejected Christianity altogether, becoming a free thinker.” (Ulster historian Gordon Lucy, Belfast News Letter, July 23, 2018)

Ballance co-founded the Wanganui Freethought Association in 1883 and published The Freethought Review from 1883 to 1885.

He is credited with many progressive reforms, improving government relations with Maoris, and calling for the “absolute equality of the sexes.” As premier, Ballance secured the right to vote for his countrywomen, making New Zealand the first country to do so. He died at age 54 at the height of his popularity after surgery to treat an intestinal disease. (D. 1893)

“A man is not good for much unless there be something of the heretic in him; unless he has a mind so independent, honest, and courageous as to think for himself, and also to choose his own opinions.”

— The Freethought Review (Oct. 1, 1883)

Charles Booth

On this date in 1840, English entrepreneur, social researcher and philanthropist Charles Booth was born in Liverpool to Unitarians. Booth became a shipping company apprentice at age 16, and, after being orphaned in 1862, he and his brother Alfred started a skins and leather trade business, with offices in New York and Liverpool. Booth launched the Booth Steamship Company in 1866. He had campaigned in the slums of Toxteth in Liverpool for Liberal parliamentary candidacy in the 1865 election, which he lost, but witnessing the intense poverty of the slums changed the course of his life.

According to his personal writings and correspondence, this experience eventually caused him to abandon his religious faith. Instead of faith, Booth developed a strong sense of social responsibility and worked the rest of his life to improve conditions for the poor. Booth believed that party politics could not solve social problems, but, in his view, educating the electorate would. This idea motivated him to join Joseph Chamberlain’s Birmingham Education League and participate in a survey, which concluded that 25,000 Liverpool children were not in school or working.

In 1871, Booth married Mary Macaulay, cousin of Beatrice Potter (later Webb). The Booths moved to London, and socialized with others (including the Webbs) who shared their deep concern for England’s poor. Booth, a member of the Fabian Society, had also served on the Royal Commission on the Aged Poor, and served with Beatrice Webb on the Royal Commission on the Poor Law. Booth first began analyzing census figures by assisting the Lord Mayor of London’s Relief Fund, in 1884.

Unsatisfied with other surveys of London’s poverty, in 1886, Booth began work on his monumental work, Life and Labour of the People in London, which eventually totaled 17 volumes. Beatrice Webb, Mary Booth and other social reformers worked on this project at various times. While previous studies estimated that 25 percent of Londoners were in poverty, Booth’s study showed the number to be at about 35 percent. It is believed that his studies on the poor helped result, at least in part, in the Old Age Pensions Act of 1908.

By the time of his death by stroke at age 76, Booth had been made a fellow of the Royal Society and received honorary degrees from Oxford, Cambridge and Liverpool Universities. (D. 1916)

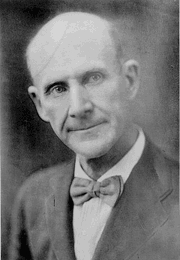

PHOTO: Wellcome Images

“Comparatively few go to church, but they strike me as very earnest-minded, and not without a religious feeling even when they say, as I have heard a man say (thinking of the evils which surrounded him), ‘If there is a God, he must be a bad one.’ “

— Charles Booth, "Life and Labour of the People in London: East, Central and South London" (1904)

Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner

On this date in 1858, Hypatia Bradlaugh (later Bonner) was born in London. The namesake of the murdered pagan lecturer of Alexandria, she was the daughter of Charles Bradlaugh, who triumphed after a long battle to be seated in Parliament as an atheist. Matriculating at London University, Bonner became a teacher at the Hall of Science run by her father’s National Secular Society. When she married Arthur Bonner in 1882, they merged their surnames and had two sons, one of whom survived.

After her father died in 1891, she wrote his biography and was forced by constant slanders of deathbed conversions to correct the public record, even taking successful court action.

An ardent opponent of the death penalty, proponent of penal reform, peace advocate and feminist, Bonner lectured widely. She founded the Rationalist Peace Society in 1910. She edited a journal, The Reformer (1897-1904). She was part of the Rationalist Press Association, worked against blasphemy laws and was appointed justice of the peace for London, serving from 1922-34, as a reward for 40 years of public service.

Her books include Penalties Upon Opinion (1912), The Christian Hell (1913) and Christianity and Conduct (1919). In her final “Testament,” she wrote, “Away with all these gods and godlings; they are worse than useless.” D. 1934.

PHOTO: Bonner in 1929, five years before she died after surgery for abdominal cancer.

"Heresy makes for progress."

— Motto of The Reformer, the journal edited by Bonner

Émile Zola

On this date in 1840, Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola was born in Paris. The novelist pioneered naturalistic writing, believing ugly problems could not be solved as long as they stayed hidden. As a struggling young writer, Zola supported himself as a clerk. Legend has it he sometimes resorted to trapping birds on his windowsill in order to eat. Zola also moonlighted as a political reporter and critic. He was fired from a publishing house after an early autobiographical novel created notoriety.

His breakthrough novel was Therese Raquin (1867). By the time his book L’Assammoir (“The Drunkard,” 1878) appeared, Zola was France’s most famous writer, yet he was barred his entire life from the Academy. His book Germinal (1885), about conditions in a coal mine leading to a strike, was denounced by the rightwing. Nana (1880) examined sexual exploitation.

Zola’s most enduring work is his open letter “J’Accuse,” about the Dreyfus case. He campaigned with Clemenceau to free the the French Jewish army officer falsely accused of spying. Zola was sentenced to imprisonment for writing “J’Accuse” in 1898, escaping to England until he could safely return after Dreyfus’ name had been cleared. Zola, who was baptized Catholic, was a notable critic of the Catholic Church (and vice versa). The church particularly condemned his books Lourdes, Rome, and Paris (1894-98). He was an honorary associate of the British Press Association. (D. 1902)

PHOTO: Zola, circa 1865.

“Given Émile Zola’s reputation as an agnostic and a radical thinker, he has often been avoided by scholars with a religious background.”

— Anthony Evenhuis, "Messiah Or Antichrist?: A Study of the Messianic Myth in the Work of Zola" (1998)

Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon

On this date in 1827, Barbara Leigh Smith (later Bodichon) was born in England. Her father was a dissenter, Universalist and benefactor to the poor. He had five children with a young milliner whom he never married, possibly out of principle. Barbara’s working class mother died young. The children grew up in an egalitarian home and Barbara received an inheritance at 21, just like her brothers. No college admitted women at the time, but she and a female friend took an unprecedented walking tour of Europe unchaperoned.

Barbara was a lifelong friend of novelist and freethinker George Eliot, who modeled “Romola” after her, and associated with many artists and intellectuals, including freethinker G.J. Holyoake. Barbara’s cousin Florence Nightingale snubbed her, evidently because of her “illegitimate” status. In 1854 she wrote a summary of laws concerning women, which became a major catalyst of the British feminist movement and resulted in the adoption of the Married Women’s Property Bill in 1857. She also petitioned Parliament for suffrage and was instrumental in the founding of Girton College in 1869, which admitted women. D. 1891.

“There was hardly a scheme for the furtherance of women's interests that did not bear the imprint of her driving aspirations. The only exception lay in projects sponsored by any branch of Christianity, for though she was not an atheist she had her own reasons for keeping her distance from organised religion. 'Ah! If you were only like Miss Barbara Smith!' Dante Gabriel Rossetti wrote to his pious and retiring sister Christina.”

— Literary critic Dinah Birch, commenting on Bodichon, London Review of Books (October 1998)

Thomas Allsop

On this date in 1795, Thomas Allsop was born near Wirksworth, Derbyshire, England. A silk trader and then stockbroker, he was a radical reformer on close terms with freethinkers such as Charles Bradlaugh. His friend G.J. Holyoake, in the Dictionary of National Biography, wrote of Allsop: “By reason of his friendships, his social position, and his boldness, he was one of the unseen forces of revolution in his day.”

A “disciple” of Samuel Coleridge, Allsop, after Coleridge’s death, collected Letters, Conversations, and Recollections of S.T. Coleridge (1836). Allsop as a Chartist supported the parliamentary candidacy of Irish radical Feargus O’Connor in 1848 and was accused of complicity in a plot to assassinate Napoleon III in 1858 but was not charged.

Holyoake wrote that when they attended the funeral of Robert Owen together, Allsop was indignant that a “mummery of an outworn creed” (a church service) would be imposed to recognize a man who had fought hard to free fellow humans from “the degradation of superstition.” (Holyoake’s Life and Last Days of R. Owen.) D. 1880.

“He despaired of amelioration from the influence of the clergy, and, when needing a house in the country, stated in an advertisement that preference would be given to one situated where no church or clergyman was to be found within five miles.”

— "Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. 1," eds. Leslie Stephen and Sidney Lee (1885)

George Jacob Holyoake

On this date in 1817, George Jacob Holyoake was born to a poor family in England. The young foundry worker attended classes in his free time, becoming a mathematics teacher. By 1840, Holyoake was a lecturer at the Worcester Hall of Science. Best-known for coining the term “secularist,” Holyoake dedicated his life to freethought. He was sentenced to six months in jail for saying England was “too poor” to support a God and should consider retiring him. He founded and edited a number of freethought journals, including Reasoner (1846-50), Leader (1850) and Secular Review (1876).

Holyoake wrote more than 160 pamphlets and works, including the books Origin and Nature of Secularism (1896), his autobiography, Sixty Years of an Agitator’s Life (1892), and the two-volume Bygones Worth Remembering (1905). He was president of the British Secular Union for many years, and became the first chair of the Rationalist Press Association.

As an Owenite, Holyoake was an ardent reformer who put causes over personal gain, helped work for women’s rights, political and educational reform, and personally aided refugees fleeing persecution. Contemporary American agnostic Robert G. Ingersoll wrote on Aug. 8, 1888: “There is no man for whom I have greater respect, greater reverence, greater love, than George Jacob Holyoake.” (D. 1906)

"Free thought means fearless thought. It is not deterred by legal penalties, nor by spiritual consequences. Dissent from the Bible does not alarm the true investigator, who takes truth for authority not authority for truth.”

— Holyoake, "The Origin and Nature of Secularism" (1896)

Clémence Royer

On this date in 1830, Clémence-Auguste Royer (née Augustine-Clémence Audouard) was born in Nantes, France. Her parents were Catholic royalists and didn’t marry until seven years after her birth. Her early education was in a convent school. Royer became a republican following the Revolution of 1848 and started to question other commonly held views. She obtained a teaching certificate and taught at girls schools in Wales, where she mastered English, and in France.

She read widely on science in these school libraries. In 1855, as a result of her inquiries, she rejected Catholicism thoroughly and devoted herself to science. She began to offer lectures on science and logic for women in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1858.

Royer translated Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species into French in 1863. She controversially added a 60-page preface which used Darwin’s mechanism for evolution as part of an anti-religious argument, which Darwin did not make. By this time the book was in its third English edition and contained several strong references to a creator. Royer had been an evolutionist before reading Darwin, having been strongly influenced by the writings of Jean Baptiste LaMarck.

French scientists, especially atheists and anthropologists, were strongly influenced by evolution and natural selection as framed by Royer, who also discussed the implications of evolutionary theory for human beings and society in her introduction. It would be almost 10 years before Darwin himself grappled with these issues in The Descent of Man. Royer continued as Darwin’s official French translator until the third French edition of Origin was published in 1870.

Royer, despite not being a research scientist, remained a popular interpreter of science as well as a philosopher of science. As a woman, she was denied access to many learned societies, as well as university teaching positions. It has been argued by Jennifer Michael Hecht and others that Royer opened doors to women within the freethinking movement. In 1866 she had a son, René, by her lover and life partner, Pascal Duprat, a married man, which sharpened her concern about the major legal obstacles then present to unwed mothers and their children.

She published many books and articles and considered the pinnacle to be Natura rerum, her theory of nature. In 1900 she was named a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor for her contributions as “a woman of letters and a scientific writer.” Royer died in 1902 at age 71. Her son died of liver failure six months later in Indochina. (D. 1902)

"Yes, I believe in revelation, but a permanent revelation of man to himself and by himself, a rational revelation that is nothing but the result of the progress of science and of the contemporary conscience, a revelation that is always only partial and relative and that is effectuated by the acquisition of new truths and even more by the elimination of ancient errors."

— Royer, preface to Darwin's "L'origine des espèces," cited in Jennifer Michael Hecht's "The End of the Soul" (2003)

Mary Wollstonecraft

On this date in 1759, feminist author Mary Wollstonecraft was born in London, the second of seven children. An industrious young woman, she worked as a governess and then opened her own school. Her first book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, was published in 1786, followed by a novel, a children’s book, a translation and The Female Reader (1789).

When Edmund Burke read her review of a sermon by dissenting minister Richard Price, he wrote a famous attack on the American and French revolutions. Wollstonecraft rebutted his polemic in her 1790 pamphlet “A Vindication of the Rights of Men, in a Letter to the Right Honourable Edmund Burke; Occasioned by His Reflections on the Revolution in France,” attacking the aristocracy and advocating for republicanism.

Her seminal A Vindication of the Rights of Woman was published in 1792. The first influential book calling for the equality of the sexes, it urged that women be educated and treated as “rational creatures.” Wollstonecraft championed dress reform, breast-feeding, early education and a national system of co-educational primary schools. She warned of those who prey “on the credulity of women.”

She gave birth to a daughter after a brief liaison with Gilbert Imlay, an American businessman, then married atheist William Godwin in March 1797. After an uneventful pregnancy, 38-year-old Mary gave birth on Aug. 30, 1797 to a second daughter, Mary, then died of an infection 10 days later. Wollstonecraft was an ardent rationalist and deist who adopted an agnostic point of view toward the end of her life. Her daughter Mary ran off as a teenager with poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and wrote Frankenstein at age 19. (D. 1797)

“Besides, in great schools, what can be more prejudicial to the moral character than the system of tyranny and abject slavery which is established amongst the boys … which makes religion worse than a farce.”

— Wollstonecraft, "A Vindication of the Rights of Woman" (1792)

Catherine the Great

On this date in 1729, Catherine II, the rationalist Empress of Russia, was born as Sophie Augusta Friederika in the province of Pomerania in Prussia. The daughter of the prince of Anhalt-Serbst, she was groomed at 14 to be the future wife of Peter, the disreputable heir to the Russian throne. Sophie moved to Moscow to be educated for her position. Her name changed to Catherine when she was received into the Russian Orthodox Church and married in 1745. She and colleagues, allegedly including her lover Orlov, deposed Peter III in a popular coup d’etat in 1762, when she assumed the throne at age 33 as Catherine II.

Catherine admired and corresponded with French rationalists such as Voltaire and Diderot, launched reforms, transformed St. Petersburg, wrote stories, and was a patron of the arts who helped to pave the way for the great 19th-century flowering of art, music and literature in Russia. She had an outsized need for affection and adulation, bonding with a dozen known lovers, but the more salacious myths about her were likely started by her political enemies.

Along with diplomatic methods, she used the military to violently expand her empire’s borders. More positively, she reformed the judiciary and governmental administration. She founded Russia’s first government funded library and women’s school, promoted a national education system and wrote a progressive legal code known as the Nakaz which, although never implemented, served as a widely respected and visionary template for future governments even beyond her borders.

Catherine responded to peasant revolts and the French Revolution with increasing conservatism and remained a Deist until her death at age 67 of a stroke. (D. 1796)

"As Empress, Catherine endeavoured to enforce the enlightened humanitarian views of the great French Rationalists, with whom she was in complete sympathy. Her reforms, in regard to education, justice, sanitation, industry, etc., were of great value."

— Joseph McCabe, "A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists"

Thomas Huxley

On this date in 1825, Thomas Henry Huxley was born in England. Huxley coined the term “agnostic” (although George Jacob Holyoake also claimed that honor). Huxley defined agnosticism as a method, “the essence of which lies in the rigorous application of a single principle … the axiom that every man should be able to give a reason for the faith that is in him.” Huxley elaborated: “In matters of the intellect, follow your reason as far as it will take you, without any other consideration. And negatively, in matters of the intellect do not pretend that conclusions are certain which are not demonstrated or demonstrable.” (From his essay “Agnosticism.”)

Huxley received his medical degree from Charing Cross School of Medicine, becoming a physiologist. He had spent his youth exploring science, especially zoology and anatomy, lecturing on natural history and writing for scientific publications. He was president of the Royal Society and was elected to the London School Board in 1870, where he championed a number of common-sense reforms.

Huxley earned the nickname “Darwin’s Bulldog” when he debated Darwin’s On the Origin of Species with Bishop Samuel Wilberforce in Oxford in 1860. When Wilberforce asked him which side of his family contained the ape, Huxley famously replied that he would prefer to descend from an ape than a human being who used his intellect “for the mere purpose of introducing ridicule into grave scientific discussion.”

Thereafter, Huxley devoted his time to the defense of science over religion. His essays included “Agnosticism and Christianity” (1889). His three rationalist grandsons were biologist Sir Julian Huxley, novelist Aldous Huxley and Henry Fielding Huxley, co-winner of a 1963 Nobel Prize. Huxley, appropriately, received the Darwin Medal in 1894. (D. 1895)

"Skepticism is the highest duty and blind faith the one unpardonable sin."

— Huxley, "Essays on Controversial Questions" (1889)

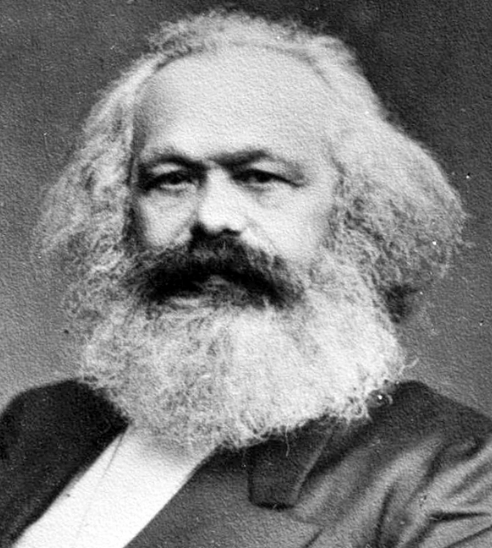

Karl Marx

On this date in 1818, Karl Heinrich Marx, descended from a long line of rabbis, was born in the Prussian Rhineland. His father converted to Protestantism shortly before Marx’s birth. Educated at the Universities of Bonn, Jena and Berlin, Marx started writing for the German language, socialist newspaper Vorwärts! (Forward) in 1844 in Paris. After being expelled from France at the urging of the Prussian government, which “banished” him in absentia, he studied economics in Brussels.

He and Friedrich Engels founded the Communist League in 1847 and published the Communist Manifesto. After the failed revolution of 1848 in Germany, in which Marx participated, he eventually wound up in London. Marx worked as foreign correspondent for several U.S. publications. His Das Kapital came out in three volumes (1867, 1885 and 1894). He organized the International and helped found the Social Democratic Party of Germany.

Although Marx was an atheist, Bertrand Russell later remarked, “His belief that there is a cosmic force called Dialectical Materialism which governs human history independently of human volitions, is mere mythology.” (Portraits From Memory, 1956) Marx once quipped, “All I know is that I am not a Marxist.” (According to Engels in a letter to C. Schmidt; Who’s Who in Hell by Warren Allen Smith)

He married German theater critic and political activist Jenny von Westphalen in 1843. They had seven children. Only three survived to adulthood. In poor health for much of his life, he died at age 64 in London, two years after his wife. (D. 1883)

PHOTO: Marx in 1875.

"Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the feelings of a heartless world, just as it is the spirit of unspiritual conditions. It is the opium of the people."

"The first requisite of the happiness of the people is the abolition of religion."— Marx, "A Criticism of the Hegelian Philosophy of Right" (1844)

Robert Owen

On this date in 1771, reformer and philanthropist Robert Owen was born in Newtown, Wales. He became known as “a capitalist who became the first Socialist.” Owen started work as a clerk at age 9. With help from a sympathetic cloth merchant to whom he was apprenticed, Owen educated himself. He was an unbeliever by 14, influenced by Seneca, and his acquaintance with chemist John Dalton and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

By 18, Owen established a small spinning mill in Manchester. In 1799 he married Ann Dale, the daughter of a Glasgow cotton manufacturer, purchasing his father-in-law’s New Lanark mills in Scotland. Owen set out to put his humanitarian creed into practice and turned New Lanark into a model community attracting the attention of reformers around the world.

Owen set up the first infant school in Great Britain and a three-grade school for children under 10. He appealed to the government and other manufacturers to follow his lead but was rebuffed by clergy-led opposition when his views on religion became widely known. At an 1817 public meeting calling for “villages of unity and cooperation,” living wages and education of the poor at the City of London Tavern, Owen called “all religions” false.

He sought to limit hours for child labor in mills in 1815 and saw passage of a watered-down Factory Act in 1819. Owen’s Essays on the Principle of the Formation of Human Character (1816) were his major treatises, in which he advised, “Relieve the human mind from useless and superstitious restraints.”

He founded New Harmony, a model settlement in Indiana in 1825-28, a failed venture which he signed over to his sons Robert Dale and William Owen. Owen wrote Debate on the Evidences of Christianity (1829). Owen founded The Economist in 1821 to promote his progressive views and The New Moral World in 1834, along with an ethical movement called “Rational Religion.”

His “Halls of Science” attracted thousands of nonreligious followers (“Owenites”) and many trade unionists. An essay titled “Scientific Socialism: The Case of Robert Owen” by David Leopold describes the Halls of Science as:

“a base for ‘social missionaries’ and cultural and leisure activities for members (typically drawn from the best paid strata of the working class). By 1840 there were over sixty branches, with weekly events — including dances, concerts, lectures, and debates (all with a whiff of teetotalism) — ‘instituted to improve the habits and manners of the working classes, and more generally to cultivate kindly feeling and social fellowship among all classes.’ Owenite events sometimes shadowed the Christian calendar, with branches providing Owenite sermons and hymns on Sundays, and even Owenite rites for baptisms, marriages, and funerals.”

His autobiography was published in 1857-58. Joseph McCabe called him “the father of British reformers, and one of the highest-minded men Britain ever produced.” (Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists, 1920.) (D. 1858)

"Finding that no religion is based on facts and cannot therefore be true, I began to reflect what must be the condition of mankind trained from infancy to believe in errors."

— Owen, "Evidences of Christianity: A Debate with Alexander Campbell and Robert Owen" (1829)

Graham Wallas

On this date in 1858, political scientist, public official and educator Graham Wallas, the son of a puritanical clergyman, was born in Sunderland, England. He studied at Corpus Christi College at Oxford where he abandoned religion in favor of rationalism. To avoid participating in communion, he resigned in 1885 from his teaching post at Highgate School in London, where he was president of the Rationalist Press Association. In 1886, Wallas joined the Fabian Society, and befriended George Bernard Shaw, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, and co-founded the London School of Economics with them.

He was an outspoken critic of the misuse of Darwin’s work by proponents of the then-popular “social Darwinism.” He also believed very strongly in representative government and, in the face of great opposition, said the solution was not to do away with representative government but to increase participation by citizens. Wallas resigned from the Fabians in 1904 over political disagreements.

He joined the faculty of the London School of Economics in 1895 and taught there until his retirement in 1923. He served on the London County Council from 1904 to 1907, chaired the school of management committee of the London School Board and in 1914 became a professor of political science at the University of London.

Among Wallas’s many publications are Property Under Socialism (1889), Human Nature in Politics (1908) — a pioneering work on applying psychology to political analysis — The Great Society (1914) and The Art of Thought (1926). Wallas wrote in Human Nature in Politics: “Plato … proposed that the loyalty of the subject-classes in his Republic should be secured once for all by religious faith. His rulers were to establish and teach a religion in which they need not believe. They were to tell their people ‘one magnificent lie’; a remedy which in its ultimate effect on the character of their rule might have been worse than the disease which it was intended to cure.” (D. 1932)

"People in a state of strong religious emotion sometimes become conscious of a throbbing sound in their ears, due to the increased force of their circulation. An organist, by opening the thirty-two-foot pipe, can create the same sensation, and can thereby induce in the congregation a vague and half-conscious belief that they are experiencing religious emotion."

— Wallas, "Human Nature in Politics, Non-Rational Inference in Politics" (1908)

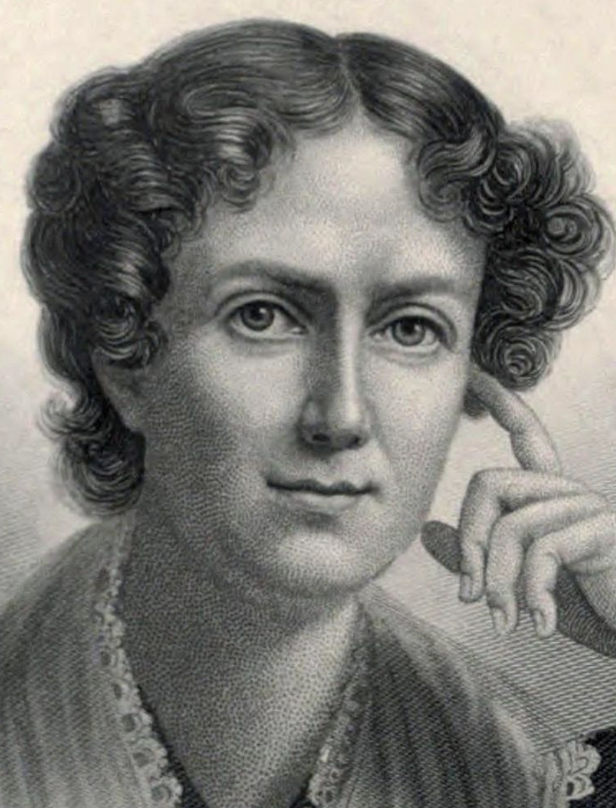

Harriet Martineau

On this date in 1802, Harriet Martineau was born in Norwich, England. The sixth of eight children of a textile manufacturer, she recoiled from her family’s Christian brand of Unitarianism, such as chapel admonitions for children and servants to obey their masters. She went through a devout teenage phase, but as an adult she wrote of Unitarianism: “I disclaim their theology in toto.” Martineau began losing her senses of taste and smell at a young age, becoming increasingly deaf. She turned to writing to help out her family and by 1830 had gained some renown. She blazed a path for women by supporting herself with her nonfiction, writing 50 books and more than 1,600 articles, signed in her own name.

In her memoirs, she boasted of being “probably the happiest single woman in England.” (She never married.) Her two-volume Society in America, as acclaimed as de Tocqueville’s look at life in America, was a definitive work on the status of American women, whom she found unhealthily obsessed with religion. Because of her scrupulous methods of observation, she is credited by some with being the “first sociologist.” Still anthologized is her essay “The Hour and the Man,” a tribute to Haitian slave liberator Toussaint L’Ouverture. After visiting the Mideast with friends, Martineau wrote an examination of the genealogy of Egyptian, Hebrew, Christian and Islamic faiths, Eastern Life: Past and Present (1848). Critics pounced on the “mocking spirit of infidelity.”

Her 1851 book, On the Laws of Man’s Nature and Development, featuring published letters between herself and H.G. Atkinson, made clear her freethought views (see quote below). Wanting to offer children an alternative to “pernicious superstition,” she wrote Household Education (1848) as a secular guide to parents. She translated and condensed the six volumes of French atheist and philosopher Auguste Comte into two volumes, with his approval, in 1853. An erroneous prognosis by a doctor telling her she had fatal heart disease in 1855 propelled her to write her autobiography. She recorded that believers, hearing of her (misdiagnosed) illness, swamped her with self-righteous religious propaganda, such as the New Testament (“as if I had never seen one before”).

When Martineau died in 1876 at age 74, Florence Nightingale wrote that she “was born to be a destroyer of slavery, in whatever form, in whatever place, all over the world, wherever she saw or thought she saw it.”

PHOTO: Martineau, c. 1834, cropped from an oil painting by Richard Evans.

"There is no theory of a God, of an author of Nature, of an origin of the Universe, which is not utterly repugnant to my faculties."

— Harriet Martineau, "On the Laws of Man's Nature and Development" (1851)

Emma Goldman

On this date in 1869, Emma Goldman was born in Russia. “Since my earliest recollection of my youth in Russia I have rebelled against orthodoxy in every form,” she wrote in her 1934 article “Was My Life Worth Living?” Told by her father that “a Jewish daughter” needed only to prepare for marriage, the defiant 17-year-old emigrated with her sister to New York, taking factory work. After the 1887 Haymarket bombing and execution of arguably innocent anarchists in Chicago, Goldman threw herself into her “ecstatic song” of political oratory.

She and Alexander “Sasha” Berkman dedicated themselves to a “supreme act” for which Berkman spent 14 years in prison — attacking Henry Clay Frick, chair of Carnegie Steel Corp. Goldman would later repudiate her youthful conviction that the ends justified the means. She was arrested numerous times as a famed orator and went underground when a self-professed anarchist madman in 1901 assassinated President William McKinley, saying he had once attended one of her lectures.

In 1906 she launched the journal Mother Earth. In 1916 she was sent to prison for advocating that “women need not always keep their mouths shut and their wombs open.” In 1917 she was arrested, convicted and served two years in prison for setting up the No Conscription League. A warden said women worshipped her like an idol because she nursed and fought for women prisoners.

Goldman wrote in 1897: “I demand the independence of woman, her right to support herself; to live for herself; to love whomever she pleases, or as many as she pleases. I demand freedom for both sexes, freedom of action, freedom in love and freedom in motherhood.”

At age 50 in 1919, she and 247 other “Reds” were deported to the Soviet Union through the efforts of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. Thoroughly disillusioned with Bolshevism, she became a British citizen in 1925. Maureen Stapleton portrayed her in the 1981 movie “Reds” that garnered her several Best Actress nominations and awards.

Golman wrote her autobiography in 1931. Her two essays, “The Failure of Christianity” (1913) and “The Philosophy of Atheism” (1916) contain her freethought views. She died in Toronto after suffering a stroke at age 70. (D. 1940)

PHOTO: Goldman, c. 1911, Library of Congress.

"I do not believe in God, because I believe in man. Whatever his mistakes, man has for thousands of years been working to undo the botched job your god has made. There are … some potentates I would kill by any and all means at my disposal. They are Ignorance, Superstition, and Bigotry — the most sinister and tyrannical rulers on earth."

— Goldman, 1898 Detroit speech titled "Living My Life"

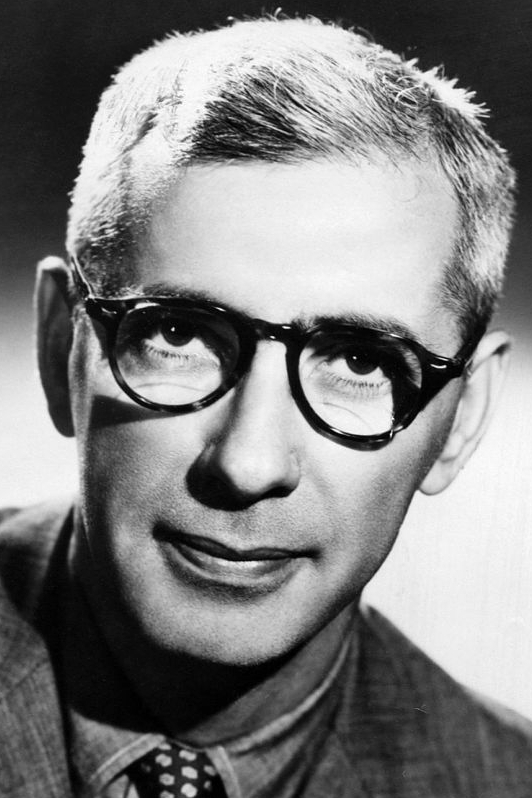

Ashley Montagu

On this date in 1905, Ashley Montagu (born Israel Ehrenberg) was born in East London. He adopted his new last name in homage of Lady Mary Montagu, a freethinking feminist from the 18th century. Montagu graduated from the University College- London and received a Ph.D. in anthropology from Columbia University in 1937. He broke ground as an anthropologist in writing about race. His book Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race (1942) was his most influential work on that score.

Some of his 60 other books included Coming Into Being of the Australian Aborigines (1937), Race and Kindred Delusions (1939) and The Natural Superiority of Women (1953). Montagu applied his work as a social biologist in writing on diverse topics, including gun control, peace, evolution, marriage, children, emotions and even a biography, The Elephant Man, about the Victorian John Merrick, which was made into a movie in 1980. His numerous articles, popular and scientific, included “Nothing Can Be Said in Favor of Smoking” (1942). The American Humanist Association named the humanitarian “Humanist of the Year” in 1995.

A statement often attributed to him (primary source unknown): “The Good Book — one of the most remarkable euphemisms ever coined.” (D. 1999)

PHOTO: Montagu at age 53 in 1958.

“The scientist believes in proof without certainty, the bigot in certainty without proof. Let us never forget that tyranny most often springs from a fanatical faith in the absoluteness of one's beliefs.”

— Montagu, "Science and Creationism" (1984)

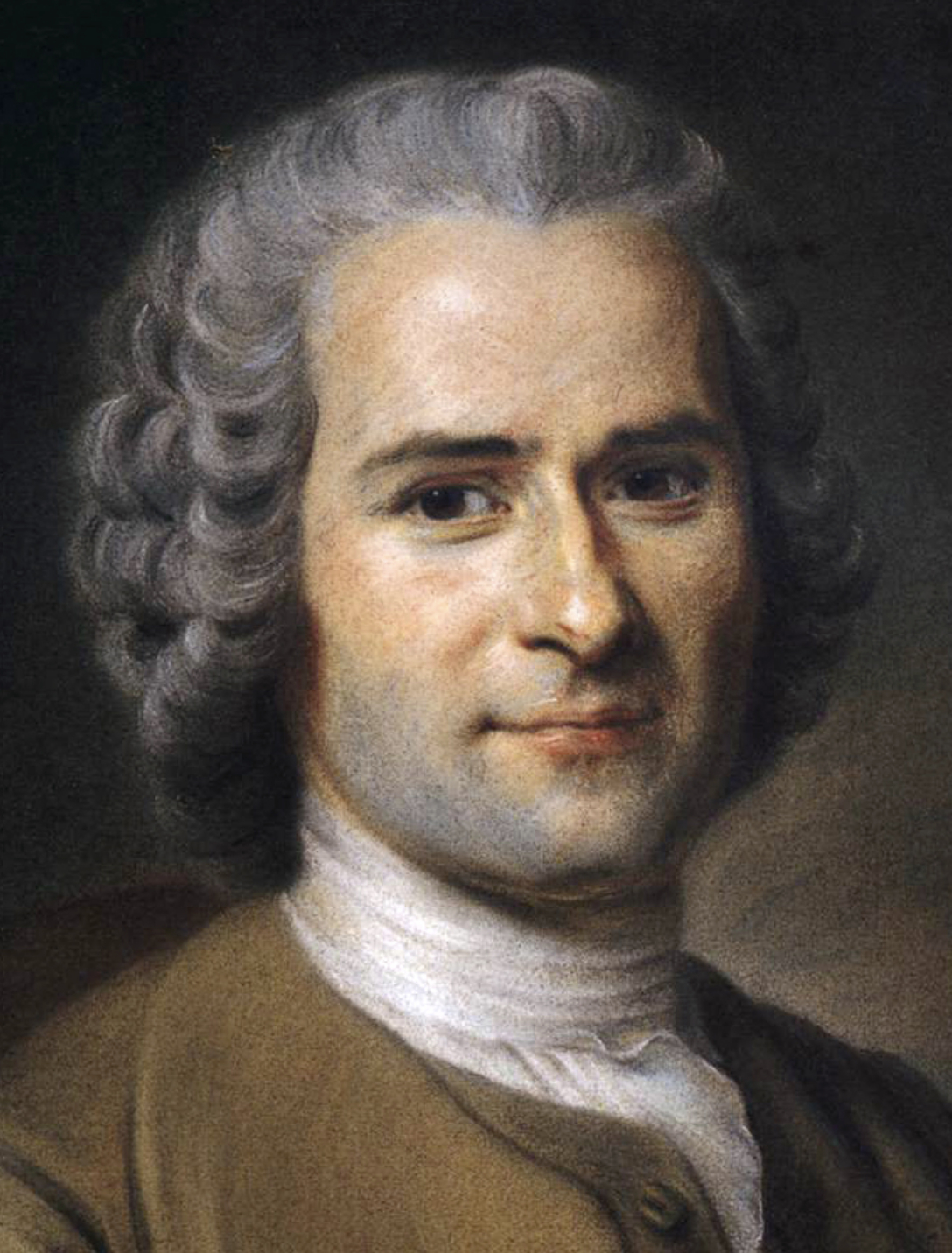

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

On this date in 1712, Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born in Geneva, Switzerland, of French Huguenot parents. His mother died giving birth to him. As a young lad he was apprenticed to an engraver but ran away at age 16 and went into domestic service. His Catholic employer, Mme. De Warens, took him as her lover and allowed him to study literature and philosophy.

In 1741 he moved to Paris and met freethinkers Diderot and D’Holbach, and was asked to write about music for the Dictionnaire Encyclopedique. Rousseau is known for promulgating the idea of the “noble savage” living in a “state of nature,” but intellectual historian Arthur Lovejoy wrote that that misrepresents Rosseau’s thinking.

While living with wealthy patrons, Rousseau worked for eight years writing the novel Julie, ou la nouvelle New Heloise (1760), The Social Contract (1762) and Emile (1762), a treatise on education. The Social Contract introduced the motto “Liberte, egalite, fraternite.” As a Deist with kind words for the gospels, Rousseau was less radical about religion than his friends, perhaps more interested in pursuing his romantic vision of human nature: “Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains.” He believed in a “religion of man.”

Despite Emile’s sympathetic words for the rights of children, Rousseau gave the five illegitimate children he fathered with a hotel maid to foundling homes. His Letters Written to Montaigne (1762) promoted freedom from the church. His arrest was ordered in Paris after publication of Emile and he fled to Switzerland, where officials, in addition to condemning Emile, also condemned The Social Contract and expelled him. Rousseau took refuge in Neuchatel under the King of Prussia but was eventually driven out for his “irreligion.”

He wrote Confessions in England and resettled in Paris in 1770. Freethought biographer Joseph McCabe wrote, “His character was far inferior to that of the ‘irreligious’ Deists of Paris. He was, in fact, the most religious and least virtuous of ‘the philosophers’; far inferior in nobility of character to the Agnostics Diderot and D’Alembert, and more faulty than Voltaire. We must, however, not forget his unhappy circumstances and temperament. He rendered monumental service to his fellows.” (A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists.) (D. 1778)

PHOTO: Portrait of Rosseau by Maurice Quentin de La Tour, 1753.

“Whoever dares to say: ‘Outside the Church is no salvation,’ ought to be driven from the State.

But I am mistaken in speaking of a Christian republic; the terms are mutually exclusive. Christianity preaches only servitude and dependence. Its spirit is so favorable to tyranny that it always profits by such a regime. True Christians are made to be slaves, and they know it and do not much mind: this short life counts for too little in their eyes.”

— Rousseau, "The Social Contract" (1762)

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

On this date in 1860, Charlotte Perkins Gilman was born in Hartford, Conn. A poet, author, editor and theorist, Gilman became one of the most celebrated feminists of her day. Her father, who virtually abandoned the family, was the grandson of evangelist Lyman Beecher. She educated herself, embracing daily exercises and eschewing corsets. She married artist Charles Walter Stetson when she was 23. She suffered paralyzing depression brought on after giving birth in 1885 to her daughter Katherine. It’s detailed in her 1890 classic story “The Yellow Wallpaper.”

After separating from her husband, she launched a career as lecturer, journalist and author. Her collection of poems, In This Our World (1893), includes a poem “To the Preacher,” which jeers: “Preach about yesterday, Preacher! … Preach about the other man, Preacher!/Not about me!” When she attended her first National American Woman Suffrage Association convention in 1896, a sister feminist wrote that Gilman had “originality flashing from her at every turn like light from a diamond.” She defended Elizabeth Cady Stanton‘s Woman’s Bible when the delegation passed a resolution against it. Woman and Economics (1898) made her an international figure.

Her thoughts on race were less than enlightened. In “A Suggestion on the Negro Problem” in the American Journal of Sociology in 1909, she wrote, “We have to consider the unavoidable presence of a large body of aliens, of a race widely dissimilar and in many respects inferior, whose present status is to us a social injury. If we had left them alone in their own country this dissimilarity and inferiority would be, so to speak, none of our business. There are other races, similarly distinguished, whose special standing in racial evolution does not embarrass us; but in this case it does.” According to biographer Cynthia Davis, Gilman once said on a trip to London, “I am an Anglo-Saxon before everything” and claimed that non-British immigrants to America were diluting the nation’s reproductive purity.

Other nonfiction included Concerning Children (1901), Human Work (1904), The Man-Made World; or, Our Adrocentric Culture (1911), and His Religion and Hers: A Study of the Faith of Our Fathers and the Work of Our Mothers (1923). In that work, she called for a religion free of patriarchy and wrote, “One religion after another has accepted and perpetuated man’s original mistake in making a private servant of the mother of the race.” In one of her poems she wrote, “What you think may guide our acts / But it does not alter facts.” She once asked,”What glory was there in an omnipotent being torturing forever a puny little creature who could in no way defend himself?”

She found happiness in her 35-year marriage to George Houghton Gilman and wrote her autobiography, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, in 1935. That year Gilman, a firm believer in euthanasia, took her own life using chloroform when pain from inoperable breast cancer became unbearable. (D. 1935)

Preach about the other man, Preacher!

The man we all can see!

The man of oaths, the man of strife,

The man who drinks and beats his wife,

Who helps his mates to fret and shirk

When all they need is to keep at work —

Preach about the other man, Preacher!

Not about me!— From Gilman's poem "To the Preacher" in the collection "In This Our World" (1893)

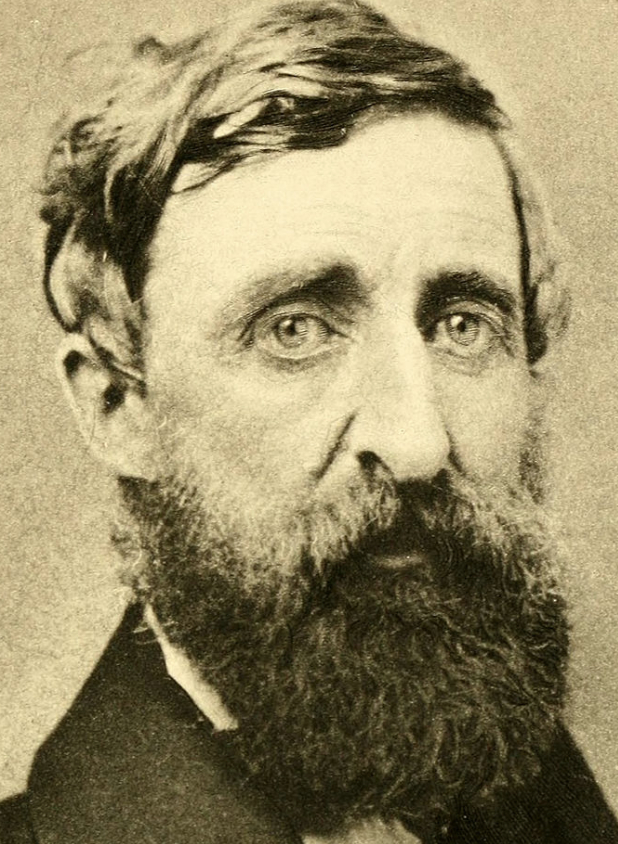

Henry David Thoreau

On this date in 1817, Henry David Thoreau was born in Massachusetts. He graduated from Harvard University in 1837, taught briefly, then turned to writing and lecturing. Becoming a Transcendentalist and good friend of Emerson, Thoreau lived the life of simplicity he advocated in his writings. His two-year experience in a hut in Walden, on land owned by Emerson, resulted in the classic Walden: Life in the Woods (1854). During his sojourn there, Thoreau refused to pay a poll tax in protest of slavery and the Mexican War, for which he was jailed overnight.

His activist convictions were expressed in the groundbreaking On the Duty of Civil Disobedience (1849). Thoreau liked to quote Ennius: “I say there are gods, but they care not what men do.” In a diary he noted his disapproval of attempts to convert the Algonquins “from their own superstitions to new ones.”

In a journal he noted wryly that it was appropriate for a church to be the ugliest building in a village, “because it is the one in which human nature stoops to the lowest and is the most disgraced.” (Cited by James A. Haught in 2000 Years of Disbelief.) When Parker Pillsbury sought to talk about religion as Thoreau was dying from tuberculosis, Thoreau replied: “One world at a time.” (D. 1862)

"Your church is a baby-house made of blocks."

— Thoreau, "On the Duty of Civil Disobedience" (1849)

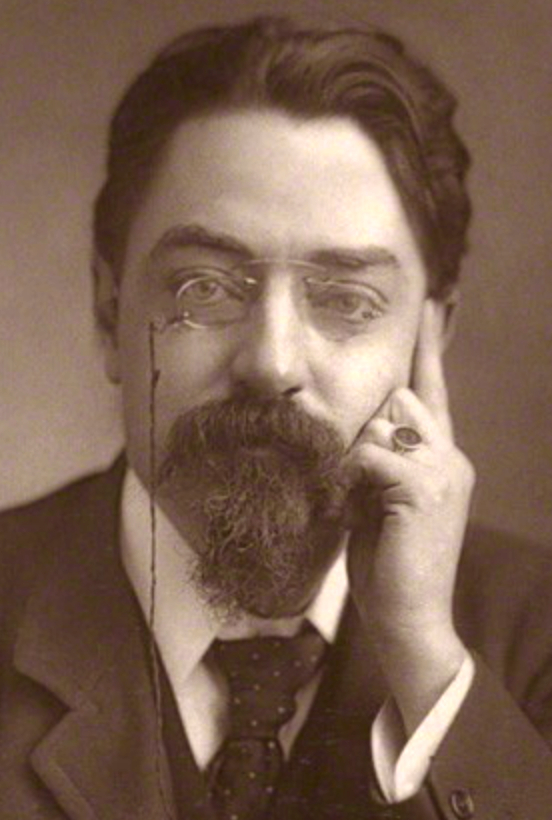

Sidney Webb

On this date in 1859, Sidney Webb was born in London. His father, an accountant, was an avowed socialist. Webb taught himself to read at an early age and as a teen became a clerk in the city of London. In 1886 he earned a law degree from London University and became a freelance journalist on the side. Webb befriended the famous playwright, socialist and fellow freethinker George Bernard Shaw and together they became the heart of the Fabian Society.

Originally the society’s goals aimed at spiritual discovery, but Webb and others reoriented the agenda to political instead of religious values. It developed into an influential intellectual movement.

Webb married a freethinker from high society and, as many friends described, his intellectual soulmate, Beatrice Potter, in 1892. In the same year, Webb won election to Parliament as a Progressive candidate. Webb and Potter together published numerous writings on social reform, including their first book The History of Trade Unionism (1894), edited by Shaw. Webb and Potter were among the first to devise a national health care plan, the origins of Britain’s National Health Service.

Together they founded, along with Shaw, Graham Wallas and others, the London School of Economics, the first social science research school of its kind. “The aim of the School was the betterment of society. By studying poverty issues and analysing inequalities, the Webbs sought to improve society in general” (London School of Economics website.) After their marriage, they devoted the rest of their lives to social reform and education. (D. 1947)

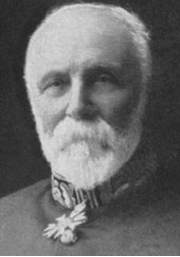

PHOTO: Webb at age 24.

"[False] generalizations [about socialism] are accordingly now to be met with only in leading articles, sermons, or the speeches of Ministers or Bishops.”

— Webb, "Fabian Essays in Socialism," ed. G.B. Shaw (1908)

Felix Adler

On this date in 1851, Felix Adler, founder of the Society for Ethical Culture, was born in Germany, the son of a Reform rabbi. At 6 he emigrated with his family to New York City. Adler graduated from Columbia College and returned to Germany for advanced study, earning a Ph.D. at the University of Heidelberg. He accepted a position in 1874 at Cornell University as a professor of Hebrew and Oriental literature.

In 1876 he was invited to give a lecture to a group interested in his ideas on a creedless ethical movement, a moral “universal religion” without a deity at its base. The next year the New York Society for Ethical Culture was incorporated and went on to initiate social reforms such as model tenements, the founding of a free kindergarten in 1878, free legal aid to the poor and child labor laws. Adler chaired the National Child Labor Committee from 1904-21.

His published lectures included Creed and Deed (1880), The Moral Instruction of Children (1892), Life and Destiny (1903), The Essentials of Spirituality, Marriage and Divorce, (1905), The Religion of Duty (1905), The World Crisis and Its Meaning (1915) and An Ethical Philosophy of Life (1918).

The International Journal of Ethics, founded by Adler in 1890, is still published by the University of Chicago Press as Ethics. Adler became professor of social and political ethics at Columbia, teaching from 1902 until his death. He also founded Ethical Culture schools, including the Fieldston School in Riverdale, N.Y., endowed by John D. Rockefeller. (D. 1933)

"For more than three thousand years men have quarreled concerning the formulas of their faith. The earth has been drenched with blood shed in this cause, the face of day darkened with the blackness of the crimes perpetrated in its name. There have been no dirtier wars than religious wars, no bitterer hates than religious hates, no fiendish cruelty like religious cruelty, no baser baseness than religious baseness.”— Adler, founding address of New York Society for Ethical Culture (May 15, 1876)

Barbara Ehrenreich

On this date in 1941, author Barbara Ehrenreich was born in Butte, Montana. She graduated from Reed College in 1963 and earned her Ph.D. at Rockefeller University in 1968, working in the field of science, then turning to writing. Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers (1972), co-written with Deirdre English, was a widely acclaimed exposé of male domination of female health care. Her essays are regularly featured in mass-circulation periodicals such as The Nation, Ms., Mother Jones, Esquire, Vogue and The New York Times Magazine.

For many years she was a regular columnist for Time. Other books include For Her Own Good: One Hundred Fifty Years of the Experts’ Advice to Women (with Deirdre English, 1978), The Hearts of Men (1983), The Worst Years of Our Lives (1990) and the classic exposé Nickel and Dimed: On Not Getting By in America, in which she went undercover as a waitress and member of the working-class poor. Her classic article, “U.S. Patriots: Without God on Their Side,” originally appeared in Mother Jones, February/March 1981, and is reprinted in the anthology Women Without Superstition.

In an essay for The New York Times Magazine, Ehrenreich proudly described her family as “the race of ‘none,’ ” as being “the kind of people … who do not believe, who do not carry on traditions.” She was named a Freethought Heroine by FFRF in 1999. Her acceptance speech was titled “My Family Values Atheism.”

She died of a stroke at age 81 at a hospice facility near her home in Alexandria, Va. (D. 2022)

"In my parents’ general view, new things were better than old, and the very fact that some ritual had been performed in the past was a good reason for abandoning it now. Because what was the past, as our forebears knew it? Nothing but poverty, superstition and grief. ‘Think for yourself,’ Dad used to say. ‘Always ask why.’ "— Ehrenreich, The New York Times Magazine (April 5, 1992)

Jane Addams

On this date in 1860, Jane Addams was born, the eighth child of a prosperous family in Cedarville, Ill. Her mother died while pregnant when Addams was 2. Her businessman father, Quaker by conviction but not affiliation, served for many years in the state Senate. Addams entered Rockford Female Seminary at age 17, intending to pursue a medical career.

Her plans changed after she developed health problems of her own and her father died from appendicitis while vacationing with his second wife at a Green Bay hotel. She inherited $50,000 in 1881, a considerable sum at the time.

She and classmate Ellen Gate Starr, with whom she had a romantic relationship, opened a settlement home in Chicago in 1889, expanding services for the working-class poor to include a girls’ home, nursery and other amenities. Hull House was secular by Addams’ decree. She documented social conditions, worked with reformers and radicals of every stripe and wrote articles on everything from suffrage to prostitution.

She co-founded the Woman’s Peace Party in 1915 and was elected national chair. It eventually became the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. She was intimately involved with the founding of sociology as an academic field in the U.S. The Jane Addams College of Social Work is a professional school at the University of Illinois in Chicago.

Addams won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931. Although she credited Jesus in her address, “A Challenge to the Contemporary Church,” she denounced the church fathers very firmly in it: “The very word woman in the writings of the church fathers stood for the basest temptations.” While she remained a member of a Presbyterian church, Addams regularly attended and sometimes lectured at Unitarian and Ethical Society events and had a close relationship with members of the Jewish community.

Addams had a long domestic partnership with Mary Rozet Smith, who was wealthy and supported Addams’ work at Hull House and elsewhere. They were together for 40 years until 1934, when Smith died of pneumonia. Addams, who suffered a heart attack in 1926, died of cancer in 1935.

"A wise man has told us that ‘men are once for all so made that they prefer a rational world to believe in and live in.’ "

— Addams, "Twenty Years at Hull-House" (1912)

Frances Wright

On this date in 1795, Frances Wright, the first woman to publicly lecture in the United States, was born an heiress in Scotland. An arresting five feet, 10 inches as an adult, Wright influenced fashion of her day with her liberating style of ringlets and later her adoption of “Turkish trousers.” She traveled with her younger sister Camilla to America in 1818. Her play, “Altorf,” was staged to acclaim in New York in 1819, where she shocked society by using her byline as a female author.

Her travel book, Views of Society & Manners in America (1820), caused a sensation in Great Britain and abroad. Freethinker Jeremy Bentham became her mentor and General Lafayette her confidante. Returning at 29 to America, Frances became a U.S. citizen. As an early and passionate abolitionist, she began a noble but ill-fated model communal plantation to educate slaves for freedom at Nashoba, Tenn. They would have no religion but “kind feeling and kind action,” Wright decreed. The experiment unraveled for lack of money.

At 33, Wright launched her speaking career on July 4, 1828, in Cincinnati, seeking to “destroy the slavery of the mind” and counteract the effects of a religious revival on women, as well as the Christian Party in Politics movement. Wright called for the education of women and the rejection of religion. Her historic speaking tour won her adoration from progressives such as the young Walt Whitman, who recalled how “we all loved her: fell down about her.” But press and clergy dubbed Wright “The Red Harlot of Infidelity” and a “voluptuous preacher of licentiousness.”

Wright urged, “Turn your churches into halls of science, exchange your teachers of faith for expounders of nature. … Fill the vacuum of your mind!” Practicing what she preached, she purchased an old church in New York City for $7,000 and renamed it the “Hall of Science.” It opened its doors in April 1829 for lectures, a radical bookstore and at one time offered a health clinic. She and Robert Dale Owen launched The Free Enquirer and the Working Men’s Party, advocating a 10-hour workday, for which she was dubbed a “female Tom Paine” by the mayor of New York.

After an unsuccessful marriage to Frenchman Phiquepal D’Arusmont, resulting in the birth of a daughter, Wright returned to the U.S., where she lectured and wrote. When Wright divorced her husband, she tragically lost custody of her daughter. She broke her hip in a fall and died prematurely after great suffering in Cincinnati. D. 1852.

"I am not going to question your opinions. I am not going to meddle with your belief. I am not going to dictate to you mine. All that I say is, examine, inquire. Look into the nature of things. Search out the grounds of your opinions, the for and the against. Know why you believe, understand what you believe, and possess a reason for the faith that is in you."

— Frances Wright, "Divisions of Knowledge" (1828)

Jessica Mitford

On this date in 1917, “Queen of the Muckrakers” Jessica Lucy Freeman-Mitford, nicknamed Decca, was born to a markedly eccentric, religious, aristocratic family in England. Her parents were anti-Semites and notorious members of the British Union of Fascists. Two of her sisters became high-profile fascists, but by age 14 Jessica was a pacifist. Like her sister Nancy, who became a novelist (Love in a Cold Climate), Jessica also embraced a left-wing socialism. She eloped in 1937 at age 19 to marry journalist Esmond Romilly, Winston Churchill’s nephew.

They honeymooned in Spain while he wrote about his experiences in the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. Romilly joined the Royal Canadian Air Force during World War II and was killed at age 23 in 1941 during a raid over Nazi Germany. Mitford then married radical lawyer Robert Treuhaft in 1943 and was active in civil rights campaigns. She led the “White Women’s Delegation” to Mississippi seeking to save a black defendant from the death penalty. She and her husband, who were members of the American Communist Party until 1958, refused to give evidence when summoned before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

She wrote the irreverent best-seller The American Way of Death (1963) after her husband became aware of outrageous funeral costs borne by working-class families. The book enraged funeral directors and the clergy and brought government regulation to the industry. It also spurred demand for cremation. She also wrote an autobiography, Daughters and Rebels (1960), The Trial of Dr. Spock (1970), A Fine Old Conflict (1977), Kind and Unusual Punishment: The Prison Business (1973), Poison Penmanship: The Making of a Muckraker (1979) and An American Way of Birth, (1992).

Mitford died at age 78 of cancer. After a $475 cremation, a memorial service was held in San Francisco, where famous speakers lauded her mordant sense of humor and lifelong unorthodoxy. (D. 1996)

PHOTO: Mitford in 1937.

“Openness about the more shadowy corners of experience was one of the many things, along with psychiatry and religion, that Decca simply didn't ‘go in for.’ "

— "Black Sheep," book review at slate.com of "Decca: The Letters of Jessica Mitford," ed. Peter Sussman (2006)

Margaret Sanger

On this date in 1879, Margaret Louise Sanger (née Higgins), was born in Corning, N.Y., to a freethinking, Irish-born father and a Catholic Irish-American mother. Watching her mother die at age 48 of tuberculosis after bearing 11 children changed the course of Sanger’s life. As a child she was introduced to the power of the Catholic Church when the local priest locked the doors of the town hall to prevent agnostic Robert Ingersoll from speaking in Corning. She wrote in her autobiography of the spellbinding experience of hearing Ingersoll speak in the woods instead.

She would later repeatedly experience being locked out of public halls, even countries, under Catholic pressure. Her experience doing obstetrical nursing of the poor in New York City as a young mother herself galvanized her conviction that women had the right to control fertility. The turning point was witnessing the death of Sadie Sachs, 28, from a second illegal abortion. When Sachs had pleaded with her doctor for birth control, he had responded: “Tell Jake to sleep on the roof.”

Sanger researched contraception (coining the term birth control) while editing a monthly newspaper, The Woman Rebel (1914). Its primary purpose was to challenge the 1873 Comstock Act, which made it illegal to send “obscene, lewd or lascivious, immoral or indecent” publications through the mail, including articles about contraception and abortion, even if written by a physician.

Facing 45 years in prison when indicted under the law, Sanger fled the country, leaving behind a book, “Family Limitation.” It sold 10 million copies while Sanger continued research in England and the Netherlands. When she returned to the U.S. she was rearrested. After her daughter Peggy died of pneumonia in 1915, Sanger went on a headline-making speaking tour to challenge the charges, which were dropped in 1916.

That year she opened the first birth control clinic, which was raided. She spent the next two decades educating physicians about birth control and overseeing the creation of clinics across the U.S. In 1934 she brought the lawsuit that finally overturned much of the repressive Comstock Act. Over her lifetime she was jailed eight times, brought diaphragms to the U.S. and distributed them, helped develop contraceptive jelly, founded Planned Parenthood, and commissioned the creation of the birth control pill.

She was hailed as the “heroine” of history by H.G. Wells. She died at age 86 of congestive heart failure in Tucson, Ariz. (D. 1966)

"No Gods — No Masters."

— Motto of Sanger's newspaper The Woman Rebel

Upton Sinclair