freethought-activists

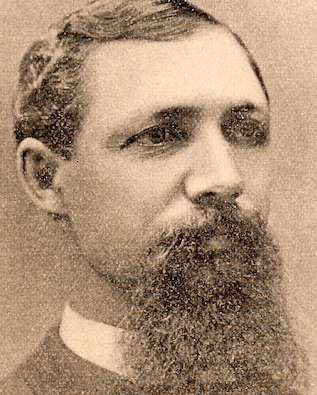

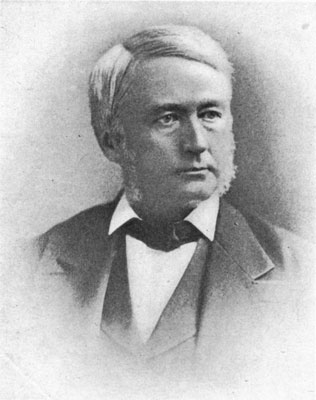

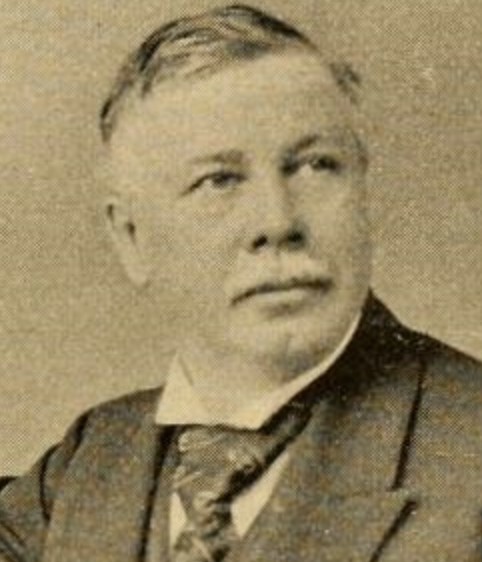

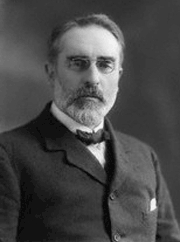

John E. Remsburg

On this day in 1848, John Eleazer Remsburg was born in Fremont, Ohio. He enlisted in the Union Army at age 16 and in 1870 married Nora Eller of Atchison, Kansas. He was a teacher for 15 years and superintendent of public instruction in Kansas for four years before becoming a freethought lecturer and writer.

His many books include Life of Thomas Paine (1880), False Claims (1883), Bible Morals (1884) and Abraham Lincoln: Was He a Christian? (1893). In his 1909 book The Christ, Remsburg listed 42 writers who did not mention Jesus or whose mentions were suspect. He wrote that the man Jesus may have existed, but that the Christ of the gospels was mythical.

He was a life member of the American Secular Union, of which he was president from 1897–1900, and a member of the Kansas State Horticultural Society. (D. 1919)

"The name of Christ has caused more persecutions, wars, and miseries than any other name has caused. The darkest wrongs are still inspired by it."

— Remsburg, from "The Christ: A Critical Review and Analysis of the Evidences of His Existence" (1909)

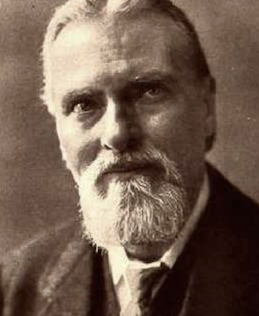

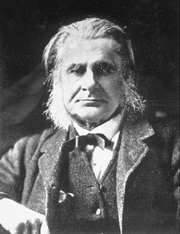

G.W. Foote

On this date in 1850, atheist activist George William Foote was born in England. In 1876 he began co-editing a weekly newspaper, The Secularist, with Jacob Holyoake, then became the first editor of the National Secular Society’s publication The Freethinker. Foote edited The Freethinker for 35 years. The magazine is still published but moved to online-only in 2014.

Foote was prosecuted for blasphemy in 1882 and jailed for a year. His plight brought reform, making future criticism of Christianity lawful in Great Britain. Foote launched several other freethought journals, publishing companies and presses, devoting his life and career to the advancement of secularism. His books include Flowers of Freethought and, with W.P. Ball, The Bible Handbook. (D. 1915)

"Who burnt heretics? Who roasted or drowned millions of ‘witches’? Who built dungeons and filled them? Who brought forth cries of agony from honest men and women that rang to the tingling stars? Who burnt Bruno? Who spat filth over the graves of Paine and Voltaire? The answer is one word — Christians."

— Foote from "Are Atheists Wicked?" (a chapter in "Flowers of Freethought," 1894)

Ruth Hurmence Green

On this date in 1915, Ruth Hurmence Green was born. The Iowa native received a journalism degree from Texas Tech in 1935, married, had three children and settled in Missouri. Green, a “half-hearted Methodist,” first plodded through the bible when convalescing from cancer in her early 60s, calling the shock she suffered from reading the book worse than the trauma caused by her illness. “There wasn’t a page of the bible that didn’t offend me in some way. There is no other book between whose covers life is so cheap,” she said, prompting her to write the enduring modern freethought classic The Born Again Skeptic’s Guide to the Bible (1979).

In the book’s preface, Green wrote: “I am now convinced that children should not be subjected to the frightfulness of the Christian religion. … If the concept of a father who plots to have his own son put to death is presented to children as beautiful and as worthy of society’s admiration, what types of human behavior can be presented to them as reprehensible?” When terminal cancer developed in 1981, Green, who always insisted “There are atheists in foxholes,” took her own life, swallowing painkillers in 1981.

In her last letter to Anne Gaylor of the Freedom From Religion Foundation on July 4, 1981, she wrote, “Freedom depends upon freethinkers.” (D. 1981)

"There was a time when religion ruled the world. It is known as the Dark Ages."

— Ruth Hurmence Green, 1980

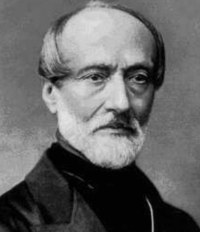

Ernestine L. Rose

On this date in 1810, Ernestine Louise Rose, née Potowski, was born in a Jewish ghetto in Poland. As the only child of an Orthodox rabbi, she was “a rebel by the age of five.” The dedicated activist became 19th-century America’s most outspoken atheist and its first lobbyist for women’s rights. Rose championed the Married Women’s Property Act first introduced by freethinking Judge Thomas Hertell in the New York Legislature in 1836, which became a model law when enacted in 1848.

After moving from Poland to England in 1830, she married William Ella Rose, a jeweler and fellow Owenite. They moved to New York in 1836 and became U.S. citizens. Rose had the distinction of being barred as an atheist from the U.S. Capitol by its chaplain in 1854. Responding to one religious heckler who turned off the gas lights during her lecture in 1853, she brought down the house by quipping that “one of the true things we find in the bible, that some there are ‘who love darkness better than light.’ ”

Known as the “Queen of the Platform,” the ringletted woman’s rights activist was frequently harassed by minister-led mobs. Her best-known freethought speech, “A Defense of Atheism,” was delivered in 1861 and is reprinted in the anthology Women Without Superstition. Rose lectured widely for women’s rights, atheism and abolition, retiring to England near the end of her life. (D. 1892)

“It is an interesting and demonstrable fact that all children are Atheists, and were religion not inculcated into their minds they would remain so.”

— Rose, "A Defense of Atheism" speech (1861)

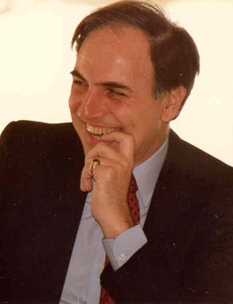

Fred Whitehead

On this date in 1944, Fred Whitehead was born in Pratt, Kansas. He graduated from the University of Kansas in 1965 and earned his Ph.D. in English from Columbia University in 1972. Whitehead, an editor and freethought historian, edited the quarterly newsletter Freethought History, which describes the history of atheism and freethought. He writes articles for publications, including Free Inquiry.

With Verle Murher, Whitehead edited Free-thought on the American Frontier (1992), a collection of essays from early freethinkers of the American West. Whitehead and Murher wrote: “From the earliest days of colonization, there has been a struggle between Christianity and freethinkers on this continent.” In 1989 Whitehead was given an Award for Exceptional Service by the Kansas Writers Association. He edited Culture Wars: Opposing Viewpoints, published in 1994.

"Far from being marginalized, as is presently the case, nineteenth-century freethought was a social movement at the core of our national life."

— "Free-thought on the American Frontier," eds. Fred Whitehead and Verle Murher (1992)

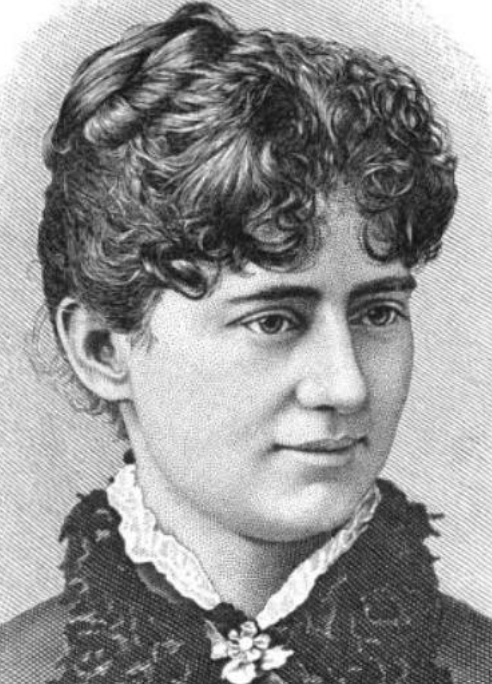

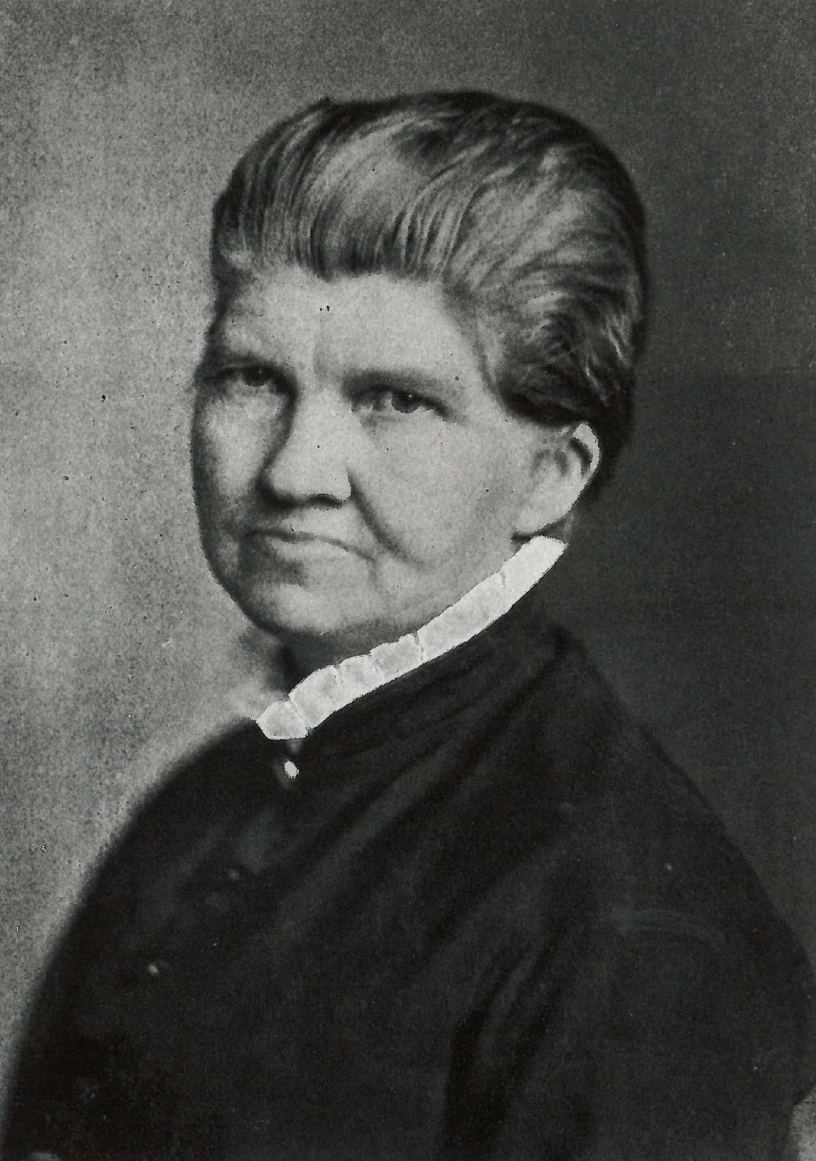

Helen H. Gardener

On this date in 1853, freethinker and suffragist Helen H. Gardener, née Alice Chenoweth, was born in Virginia, the youngest daughter of a Protestant minister who had inherited slaves but freed them in 1853 despite existing legal obstacles. Changing her name in her 30s, she became a writer in New York City, studied biology at Columbia and met “the Great Agnostic” Robert Green Ingersoll, who encouraged her to undertake a lecture series. The lectures were published in 1885 in book form, Men, Women and Gods.

A friend of feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Gardener was a member of Stanton’s Woman’s Bible Committee. Chosen by Stanton to deliver her memorial service, Gardener quipped that while most suffragists found the Woman’s Bible too radical, she found it not radical enough! She also used fiction to crusade for women’s rights, writing novels, for example, showing the harm of the scandalously low age of consent laws of her era.

In her 1885 book Men, Women, and Gods, she wrote: “I do know that women make shirts for seventy cents a dozen in this [world]. I do know that the needs of humanity and this world are infinite, unending, constant, and immediate. They will take all our time, our strength, our love, and our thoughts; and our work here will be only then begun.”

She became vice president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1917, working as chief liaison with President Woodrow Wilson’s administration, and credited with being a “worker of miracles” by sister suffragists. At age 67 she became the first woman appointed to the U.S. Civil Service Commission, serving with distinction for five years.

She died at 72 of myocarditis. She had donated her brain for scientific study before her body was cremated and its ashes interred at Arlington National Cemetery beside the grave of her second husband. Her brain is housed as part of a collection at Cornell University. (D. 1925)

PHOTO: Gardener at age 41.

"I do not know of any divine commands. I do know of most important human ones. I do not know the needs of a god or of another world.”

— Gardener, "Men, Women, and Gods, and Other Lectures" (1885)

Joseph Mazzini Wheeler

On this date in 1850, Joseph Mazzini Wheeler was born in Great Britain. Wheeler, an atheist, is best known as the author of the monumental Biographical Dictionary of Freethinkers (1889). Wheeler, who dedicated his life to freethought after moving to London in the early 1870s, was a close friend of freethought editor G.W. Foote. Wheeler also wrote Frauds and Follies of the Fathers (1888), Footsteps of the Past (1895) and co-authored Crimes of Christianity with Foote.

He served for many years as vice president of the National Secular Society and was a frequent contributor to freethought periodicals. He served as subeditor of the National Secular Society’s publication The Freethinker from its founding in 1881 to his death at age 48. (D. 1898)

"The merits and services of Christianity have been industriously extolled by its hired advocates. Every Sunday its praises are sounded from myriads of pulpits. It enjoys the prestige of an ancient establishment and the comprehensive support of the State. It has the ear of rulers and the control of education. Every generation is suborned in its favor. Those who dissent from it are losers, those who oppose it are ostracised; while in the past, for century after century, it has replied to criticism with imprisonment, and to scepticism with the dungeon and the stake."

— from "Crimes of Christianity" by J.M. Wheeler and G.W. Foote (1887)

Sherwin Wine

On this date in 1928, Sherwin T. Wine was born in Detroit, Mich. He received his bachelor’s degree in philosophy from the University of Michigan, and returned for his master’s degree in philosophy in 1951. Wine attended Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati and was ordained as a rabbi in 1956. He worked as a U.S. Army chaplain in Korea (1957–58) and an assistant rabbi at Temple Beth El in Detroit (1958–60). Wine wrote many books, including Judaism Beyond God (1985) and Staying Sane in a Crazy World (1995). He lived with his partner, Richard McCains, until Wine’s death in 2007 in Morocco from a car accident.

Born to Conservative Jewish parents, Wine began questioning the idea of a god at Hebrew Union College and gradually lost his faith. He told Time magazine in 1965: “I am an atheist,” adding, “I find no adequate reason to accept the existence of a supreme person.” (Quoted in The New York Times, July 25, 2007.) Wine’s lack of belief led him to consider the concept of Humanistic Judaism, which rejects belief in God while maintaining secular Jewish traditions, culture and ethics.

“Theological beliefs have nothing to do with Jewish identity. The Jewish people encompass theists and atheists,” Wine explained in his book Celebration (2003). He elaborated on the beliefs of Humanistic Judaism: “Humanists know that they have the right and the power to be the masters of their own lives, that they have the strength to confront the world as it is and not as fantasy makes it appear, and that they have the opportunity to serve the future and not the past.”

Wine established the Birmingham Temple in 1963 in Farmington Hills, a suburb of Detroit. At the temple, which he worked at until his retirement in 2003, Wine performed services with no mention of God, replacing prayers with poetry and Torah readings with speeches on history. Humanistic Judaism is now practiced worldwide. (D. 2007)

"If I were a CEO of a company and ran it like God runs the universe, I'd be fired."

— Wine interview, The Guardian (Sept. 18, 2007)

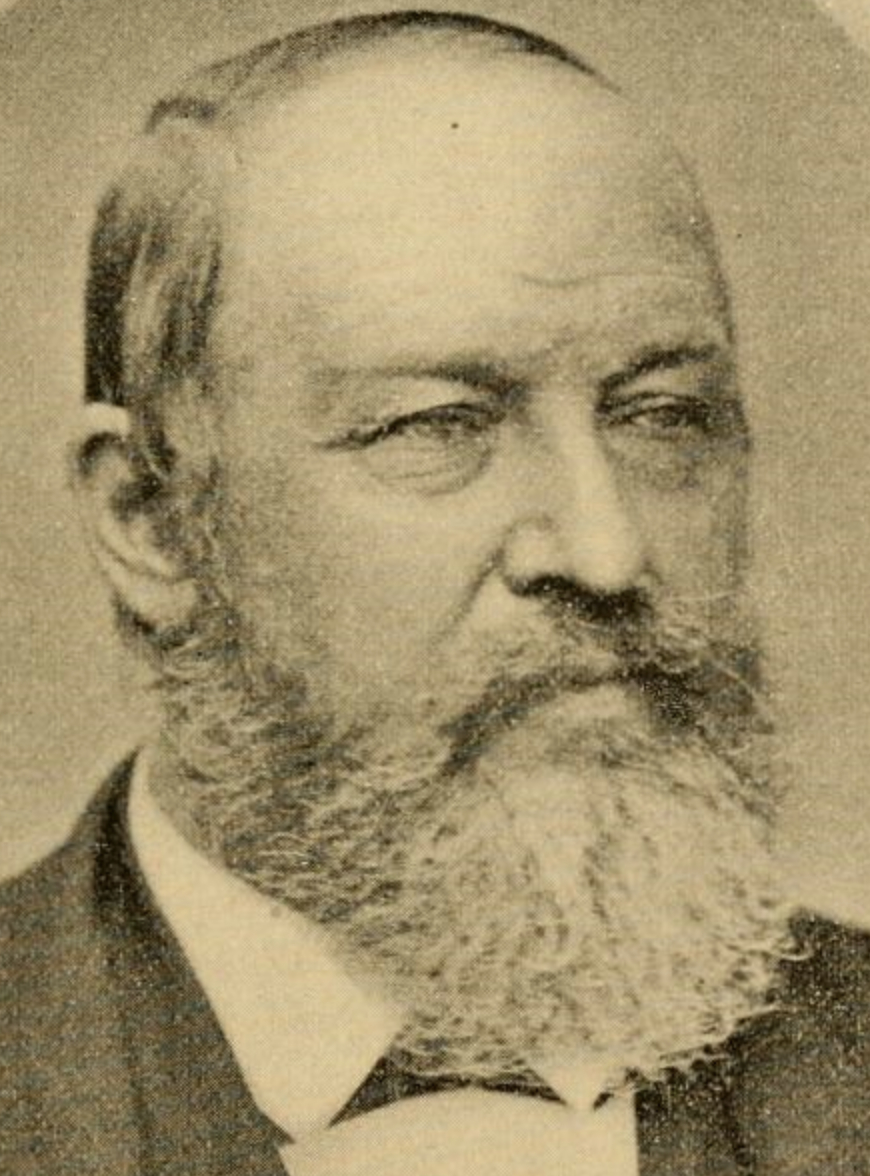

Eugene M. MacDonald

On this date in 1855, Eugene Montague MacDonald was born. The American journalist became a foreman at The Truth Seeker, a 19th-century freethought newspaper. When Truth Seeker founder D.M. Bennett died, MacDonald and two others established The Truth Seeker Company, buying the newspaper in 1883. MacDonald edited the 19th century’s leading freethought publication for 26 years. His brother George took over editorship when Eugene retired shortly before his death. Truth Seeker readers and contributors included Clarence Darrow, who wrote in 1931 that he had been connected with the publication for 50 years. (D. 1909)

PHOTO: MacDonald, c. 1883.

"The Chicago World’s Fair having been decreed, the kind of church people who adopt meddling as a means of grace saw that now was their day of salvation. Hitherto, with their fussy restrictions on Sunday work and amusements, they had been obliged to function merely as local nuisances. Now they would close the World’s Fair on Sunday and make themselves felt as pests by all nations.”

— From The Truth Seeker, 1892, cited in "Fifty Years of Freethought, Vol. II" by George MacDonald (1929)

François-Désiré Bancel

On this date in 1822, François-Désiré Bancel was born in France. He was educated at Touron and Grenoble, became a lawyer and then a member of the Legislative Assembly in 1849. Bancel was known as one of the most passionate critics of the royalists and clerics. After Napoleon III expelled him in 1852, he moved to Brussels and taught at the Free University.

A deist, according to freethought historian Joseph McCabe, he “gave great assistance in the Belgian Rationalist movement.” Bancel was again elected to the legislature in 1869 upon his return to France. A boulevard in Valence and a street in Lyon bear his name. (D. 1871)

Charles Watts

On this date in 1836, Charles Watts was born in Bristol, England, into a family of Methodists. At age 16 he moved to London to work with his older brother in a printing office. The brothers were acquainted with many freethinkers and founded a publishing business, Watts & Co., in 1864. Along with Charles Bradlaugh and others, Watts co-founded the National Secular Society in 1866.

Watts wrote extensively on freethought, including Freethought: Its Rise, Progress and Triumph (1885). In an 1868 pamphlet on Christianity, he wrote: “In Spain religion is cruel oppression, in Scotland it is a gloomy nightmare, in Rome it is priestly dominion, while in England it is simply emotional pastime. All these different phases of Christianity indicate that theological opinions depend on surrounding circumstances, and cannot therefore be the cause of the civilisation of the world.”

He emigrated to Toronto in 1883, where he lectured and became the leader of the secularist movement in Canada. Returning to England in 1891, he worked for The Freethinker, the world’s oldest surviving freethought publication (internet-only since 2014). Watts’ wife, Kate Eunice Watts, also wrote and traveled with him. Some of her writings included The Education and Position of Woman and Christianity: Defective and Unnecessary.

Watts died at age 70 and was cremated, with his remains buried in Highgate Cemetery in North London. His son, Charles Albert Watts, developed the Rationalist Press Association, still in existence as the Rationalist Association. (D. 1906)

"The object of Christ was to teach his followers how to die, rather than to instruct them how to live.”

— from Watts' pamphlet "Christianity: Its Nature and Influence on Civilisation" (1868)

Ed Schempp

On this date in 1908, Ed Schempp was born. (He was actually born on Feb. 29, a date this software wants to recognize as March 1.) He and his son Ellery launched the landmark lawsuit Abington School District v. Schempp to contest a Pennsylvania law mandating daily bible readings in public schools. The U.S. Supreme Court issued an 8-1 ruling in 1963 barring mandatory bible reading in public schools, which followed its 1962 decision barring prayer. “In the relationship between man and religion, the state is firmly committed to the position of neutrality,” Justice Tom Clark wrote for the majority. The only dissent was from Justice Potter Stewart, who wanted the case remanded to the lower courts.

A native Philadelphian, Schempp took over his father’s hardware business as a young man and later worked in electronics. He was active in Unitarianism and peace groups. He was a longtime FFRF member and honorary officer and was featured in FFRF’s 1988 film “Champions of the First Amendment.” He and his wife of 69 years, Sydney, had three children. D. 2003.

"Freedom of religion includes freedom from religion. … Why don’t we celebrate living, instead of worrying about damnation and sin?"

— Schempp, acceptance speech as 1996 Humanist of the Year, awarded by the American Humanist Association

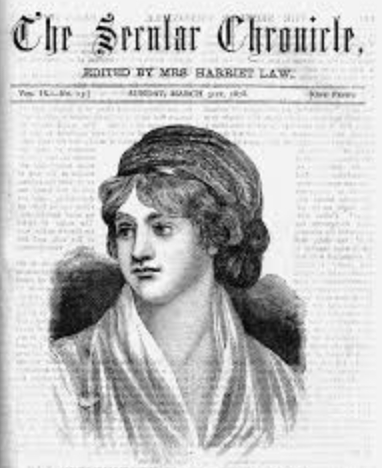

William Stewart Ross

On this date in 1844, William Stewart Ross (“Saladin”) was born in Scotland. While preparing for the ministry at Glasgow University, Ross became a rationalist and gave up the church. He set up his own publishing company, W. Stewart & Co., in London. By 1880 he was co-editor of the Secular Review. Later becoming its sole editor and owner, he changed the name to the Agnostic Journal and Secular Review in 1889 and shortly thereafter to the Agnostic Journal and Eclectic Review. The last issue was published in June 1907.

Ross was not an admirer of the famous British atheist Charles Bradlaugh, and his journal and essays represented an alternative style. He wrote under the nom de plume of “Saladin” (the Muslim fighter who halted the Third Crusade). His books include God and His Book (1887) and Woman: Her Glory and Her Shame (two volumes, 1894). In 1879 he won a gold medal for writing the best poem to memorialize the unveiling of a statue of Robert Burns. Confined in his last years due to sclerosis, he died in 1906 at age 62.

“Christianity claims to have originated lunatic asylums. If I were to claim that it was I who made the moons of Jupiter and placed the belt round Saturn, I should be nearly as preposterous as Christianity is when she claims to have originated asylums for the insane. … If the preacher would stand up in his pulpit and whine, ‘My dear Christian brethren, our blessed religion did not originate lunatic asylums; but it has made up for that by making millions of lunatics,’ he would speak only the sober truth.”

— W.S. Ross, Chapter XXXII, "God and His Book" (1887)

Matilda Joslyn Gage

On this date in 1826, suffragist Matilda Electa Gage (née Joslyn) was born in Cicero, N.Y. Her father was Dr. Hezekiah Joslyn, whose home was a station on the underground railroad and who advocated for abolition of slavery, women’s rights, freethought and temperance. She married merchant Henry Gage at age 18 and gave birth to five children, one of whom died in infancy.

A founding member and later president of the National Woman Suffrage Association, Gage expressed indignation over “the wrongs inflicted upon one-half of humanity by the other half in the name of religion.” She delivered a major address, “Woman, Church, and State,” at a suffrage convention in 1878. By popular response, she later turned this address into a book of the same name in 1893. It documented woman-hating abuses ranging from celibacy to witch hunts that stemmed from religious doctrines.

Gage convened the historic Woman’s National Liberal Union in 1890, the first feminist group devoted to the promotion of the separation of church and state. Her warning of a union of Catholics and Protestants whose agenda was to put God in the Constitution and attack secular schools, is eerily timely today: “[I]n order to help preserve the very life of the Republic, it is imperative that women should unite upon a platform of opposition to the teaching and aim of that ever most unscrupulous enemy of freedom — the Church.”

She died in Chicago at age 71. Carved on her tombstone in Fayetteville, N.Y., is her well-known motto: “There is a word sweeter than Mother, Home, or Heaven; that word is Liberty.” (D. 1898)

"During the ages, no rebellion has been of like importance with that of Woman against the tyranny of the Church and State; none has had its far reaching effects. We note its beginning; its progress will overthrow every existing form of these institutions; its end will be a regenerated world."

— "Woman, Church, and State" by Matilda Joslyn Gage (1893)

Courtlandt Palmer

On this date in 1843, writer Courtlandt Palmer was born in New York. An 1869 graduate of Columbia Law School and heir to family wealth, Palmer used both assets to promote rationalism. He had rejected the Dutch Reformed church of his family at an early age. He founded the Nineteenth Century Club to promote freethought, serving as its first president. He also wrote for The Truth Seeker and other freethought publications.

The New York Sun, in its obituary, lauded Palmer for “a surpassing feat in making fashionable in New York a sort of discussion which before had been frowned upon as in the last degree pernicious, and especially unbefitting polite and conservative society. He set people to thinking and talking over moral and religious questions, which they had not dared to consider, and made familiar to them views from which they had turned in alarm as morally poisonous and soul-destroying.

The Sun obituary continued: “The Nineteenth Century Club was established as a Freethinking debating society, and not many years ago it would have been avoided and denounced as an institution for the propagation of Infidelity and odious Radicalisms. Yet under Mr. Palmer’s lead the club received the stamp of fashionable approval, and its discussions have been carried on before crowded assemblages of ladies and gentlemen in full evening dress. … Where they had been sure there was only one possible side, they saw other people found many sides.”

The obituary also noted that Palmer’s death at age 45 of peritonitis defied the stereotype “that the deathbed of the unbeliever is an agonizing one.” It noted his final words to family were “I want you one and all to tell the whole world that you have seen a Freethinker die without the last fear of what the hereafter may be.” (D. 1888)

"He investigated for himself the questions, the problems, and the mysteries of life. Majorities were nothing to him. No error could be old enough, popular, plausible, or profitable enough, to bribe his judgment or to keep his conscience still. He was a believer in intellectual hospitality, in the fair exchange of thought, in good mental manners, in the amenities of the soul, in the chivalry of discussion. He believed in the morality of the useful, that the virtues are the friends of humanity, the seeds of joy. He lived and labored for his fellow men."

— Robert G. Ingersoll's funeral oration on behalf of Palmer, cited in "Four Hundred Years of Freethought" by S.P. Putnam (1894)

Corliss Lamont

On this date in 1902, Corliss Lamont was born in Englewood, N.J. His father, Thomas W. Lamont, was a chairman of J.P. Morgan & Co. He attended Phillips Exeter Academy and received his bachelor’s degree from Harvard University in 1924. He went on to obtain his Ph.D. in philosophy from Columbia University in 1932. Lamont supported many radical causes, including socialism, and although he never joined the Communist Party, he was strongly opposed to the persecution of communists.

He served as the director of the the American Civil Liberties Union from 1932 until 1954. He was a founder in 1954 of the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee. After being called before the House Un-American Activities Committee because of a book he had written, The Peoples of the Soviet Union (1946), he was cited for contempt of Congress. The indictment was dismissed by the Court of Appeals on the grounds that he was outside the jurisdiction of the committee.

Lamont wrote many books, pamphlets and essays, including many on humanism. His influential book The Philosophy of Humanism (1949), was based on a course he taught at Columbia in the 1940s and 1950s on naturalistic humanism. Other books on humanist subjects include his classic The Illusion of Immortality (1935), which argued against the imortality of the soul. He also wrote A Humanist Funeral Service (1954) and A Humanist Wedding Service (1970).

He was an active member for many years of the American Humanist Association and in 1977 received its Humanist of the Year award. He died of heart failure at age 93 in 1995.

"The greatest difference between the Humanist ethic and that of Christianity and the traditional religions is that it is entirely based on happiness in this one and only life and not concerned with a realm of supernatural immortality and the glory of God. Humanism denies the philosophical and psychological dualism of soul and body and contends that a human being is a oneness of mind, personality, and physical organism. Christian insistence on the resurrection of the body and personal immortality has often cut the nerve of effective action here and now, and has led to the neglect of present human welfare and happiness."

— Lamont, "The Affirmative Ethics of Humanism," The Humanist (March/April 1980)

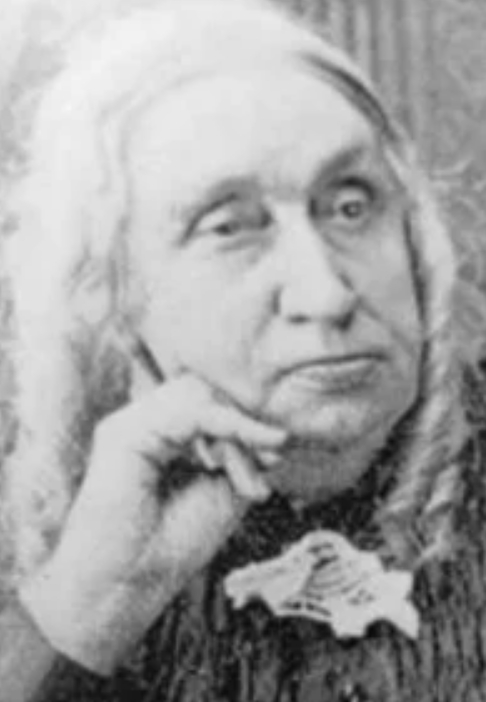

Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner

On this date in 1858, Hypatia Bradlaugh (later Bonner) was born in London. The namesake of the murdered pagan lecturer of Alexandria, she was the daughter of Charles Bradlaugh, who triumphed after a long battle to be seated in Parliament as an atheist. Matriculating at London University, Bonner became a teacher at the Hall of Science run by her father’s National Secular Society. When she married Arthur Bonner in 1882, they merged their surnames and had two sons, one of whom survived.

After her father died in 1891, she wrote his biography and was forced by constant slanders of deathbed conversions to correct the public record, even taking successful court action.

An ardent opponent of the death penalty, proponent of penal reform, peace advocate and feminist, Bonner lectured widely. She founded the Rationalist Peace Society in 1910. She edited a journal, The Reformer (1897-1904). She was part of the Rationalist Press Association, worked against blasphemy laws and was appointed justice of the peace for London, serving from 1922-34, as a reward for 40 years of public service.

Her books include Penalties Upon Opinion (1912), The Christian Hell (1913) and Christianity and Conduct (1919). In her final “Testament,” she wrote, “Away with all these gods and godlings; they are worse than useless.” D. 1934.

PHOTO: Bonner in 1929, five years before she died after surgery for abdominal cancer.

"Heresy makes for progress."

— Motto of The Reformer, the journal edited by Bonner

Lloyd Morain

On this date in 1917, Lloyd Morain was born in Pomona, Calif. He grew up in California and, after winning a scholarship essay contest, graduated from UCLA. During World War II he served in Britain with the U.S. Air Corps. Already active in the American Humanist Association, while in Britain he met with humanist groups with the goal of greater international humanist cooperation after the war. He continued this work, moving on to continental Europe, in the late 1940s.

In 1952 he and his wife, Mary Stone Dewing Morain, were among the founders of the International Humanist and Ethical Union. At the time, Morain was serving as president of the American Humanist Organization, a role he filled from 1951-55 and again from 1969-72. In the 1950s, Morain and his wife were also involved in supporting humanist organizations all over the world, including in traditionally religious regions of Africa. In 1954, they wrote the book Humanism as the Next Step: An Introduction for Liberal Protestants, Catholics, and Jews, which remains in print in a revised edition.

Morain served as the editor of Humanist Magazine from 1978-90. Though his early background was in psychological consulting, and he continued to work for the mining and utilities industries, he dedicated much of his life to humanist and social causes, including family planning and homelessness. He received several awards from AHA throughout his career: the Humanist Merit Award in 1956, the Humanist Distinguished Service Award in 1972 and the Humanist Heritage Award in 2007. In 1994 he and his wife won the Humanist of the Year Award jointly. (D. 2010)

“Back through the centuries whenever people have enjoyed keenly the sights and sounds and other sensations of the world about them, and enjoyed these for what they were — not because they stood for something else — they were experiencing life humanistically.”

— Morain, "Humanism as the Next Step" (1954)

Elihu Palmer

On this date in 1764, Elihu Palmer was born in Canterbury, Conn. Palmer graduated from Dartmouth in 1787, read theology and proved to be an unpopular minister in Presbyterian and Baptist congregations, where he spoke as a deist against the divinity of Jesus Christ. He switched to law and was admitted to the bar in Philadelphia in 1793. Yellow fever had killed his young wife and blinded Palmer.

He was invited to found the Deistical Society of New York, and lectured widely on the East Coast. He wrote orations, opinion pieces and the book Principles of Nature; or, A Development of the Moral Causes of Happiness and Misery Among the Human Species (c. 1801), in which he wrote that “the world is infinitely worse” for following Jesus.

Palmer also founded Prospect, a journal that was published from 1803-05. Unlike many deists, Palmer argued that the flawed teachings of Jesus were responsible for Christianity’s sordid history. According to Roderick C. French’s entry in Encyclopedia of Unbelief, Palmer wrote that he preferred “the correct, the elegant, the useful maxims of Confucius, Antoninus, Seneca, Price and Volney.”

When Thomas Paine was universally ostracized for writing The Age of Reason, Palmer and his second wife, who nursed Paine, remained steadfast friends. Palmer was only 42 when he died during a speaking tour. D. 1806.

"Another important doctrine of the Christian religion, is the atonement supposed to have been made by the death and sufferings of the pretended Saviour of the world; and this is grounded upon principles as regardless of justice as the doctrine of original sin. It exhibits a spectacle truly distressing to the feelings of the benevolent mind, it calls innocence and virtue into a scene of suffering, and reputed guilt, in order to destroy the injurious effects of real vice."

— Palmer, "Principles of Nature" (1801)

Abner Kneeland

On this date in 1774, Abner Kneeland was born in Massachusetts to a Congregationalist family. As a founding member of the Universalists, he served as a minister from 1804-29. When freethinker Frances Wright embarked on her famous lecture tour, becoming the first woman to speak in public in the U.S., New York City halls were closed to her. Kneeland invited her to speak from the pulpit of his Second Universalist Society in 1829, consequently lost his position and was later disfellowshipped by the church.

Kneeland’s lectures against Christianity in August 1829 were published as A Review of the Evidences of Christianity. He founded a group of freethinking New Yorkers, which met in Tammany Hall for a decade. Kneeland’s Rationalism of the Enlightenment made him a leading proponent of universal public education and the Workingmen Party.

Moving to Boston in 1830, Kneeland founded the Boston Investigator, the oldest 19th-century freethought newspaper in the U.S. His Sunday lectures to the First Society of Free Enquirers attracted crowds and the attention of influential critics. He was charged with blasphemy in 1834 for saying he did not believe in God, undergoing three trials. The prosecuting attorney for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts told the jury that if Kneeland was not punished, “marriages [will be] dissolved, prostitution made easy and safe, moral and religious restraints removed, property invaded, and the foundations of society broken up, and property made common.”

His appeal to the state Supreme Court ended with a split verdict of guilty in 1838 and he served a 60-day sentence. He moved to Iowa Territory, co-founding a freethinking settlement known as Salubria (near present-day Farmington) and becoming chair of the Van Buren County Democratic convention in 1842. An anti-infidel opposition party burned Kneeland in effigy and defeated his ticket, which was known by missionaries as “Kneelandism.”

His versatile writings included a popular spelling reader, an annotated New Testament, an edition of Voltaire‘s Philosophical Dictionary, and the two-volume The Deist (1829). D. 1844.

“Universalists believe in a god which I do not; but believe that their god, with all his moral attributes, (aside from nature itself,) is nothing more than a chimera of their own imagination.”

— Kneeland letter to Universalist editor Thomas Whittemore, Boston Investigator (Dec. 20, 1833)

Mattie Parry Krekel

On this date in 1840, freethought lecturer Mattie Parry Krekel was born in Goshen, Indiana, to John M. Hulett and Lucinda Jay (a direct descendant of revolutionary John Jay). Mattie liked to thank her parents for being liberal in their religious views, noting that her life had not been twisted or distorted by ecclesiastical influences which enslave the mind. She began lecturing at age 15 in Rockford, Illinois, and retired only in 1900. Mattie married T.W. Parry in 1862 and had six children, four sons and two daughters. Following his death she later married Judge Arnold Krekel of Missouri.

She was well-known on the freethought lecture circuit, or “Liberal platform.” Freethought biographer S.P. Putnam called her “one of the bravest and staunchest lecturers in the field … eloquent, scholarly, logical, ready for any hardship; has plenty of grit. … She is well informed on subjects pertaining to science and reform, and is in thorough sympathy with those who suffer and toil because of ignorance and superstition.” (Four Hundred Years of Freethought, 1894).

“Up to the beginning of the present century there were few names more familiar to readers of The Truth Seeker than Mattie Parry Krekel,” noted George E. Macdonald, one of the newspaper’s longest-lived editors (Fifty Years of Freethought, 1929). (D. 1921)

Christopher Hitchens

On this date in 1949, writer and columnist Christopher Eric Hitchens was born in Portsmouth, England. He attended Cambridge and graduated from Oxford in 1970, reading in philosophy, politics and economics. From 1971-81 he worked as a book reviewer for The Times of London.

In 1981 he emigrated to the United States. He wrote “Minority Report,” a column for The Nation, from 1982-2002. He then wrote for Slate, The Daily Mirror, The Atlantic Monthly, Vanity Fair, Harper’s and several other publications. As a foreign correspondent, he covered events in 60 countries on five continents. He became a U.S. citizen in 2007.

Hitchens wrote a host of books, but is best-known in freethought circles for authoring The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice (1995) and God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everthing (2007). His criticisms of President Clinton and support for President Bush’s 2003 invasion of Iraq made him increasingly controversial among progressive readership, but he remained a stalwart atheist and iconoclast. When the Freedom From Religion Foundation instituted its Honorary Board of Directors in 2010, Hitchens was a member.

In “Papal Power: John Paul II’s other legacy” (Slate.com, April 1, 2005), Hitchens pointed out that the pope “was a part of the cover-up and obstruction of justice that allowed the child-rape scandal to continue for so long.”

Hitchens married Eleni Meleagrou, a Greek Cypriot, in 1981. They had a son, Alexander, and a daughter, Sophia. After divorcing, he married Carol Blue, an American screenwriter, in a ceremony at the apartment of Victor Navasky, editor of The Nation. He and Blue had a daughter, Antonia.

After being diagnosed in 2010 with esophageal cancer, he died of pneumonia at age 62 at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. (D. 2011)

“Gullibility and credulity are considered undesirable qualities in every department of human life — except religion. … Atheism strikes me as morally superior, as well as intellectually superior, to religion. Since it is obviously inconceivable that all religions can be right, the most reasonable conclusion is that they are all wrong.”

— Hitchens, "The Lord and the Intellectuals," Harper's (July 1982)

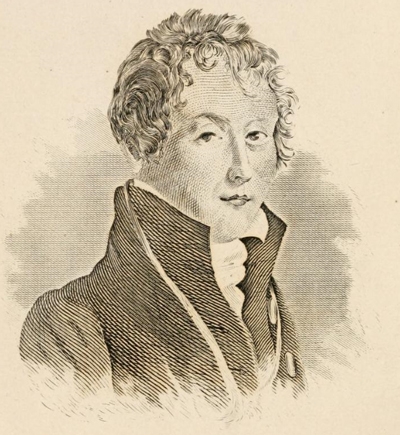

George Jacob Holyoake

On this date in 1817, George Jacob Holyoake was born to a poor family in England. The young foundry worker attended classes in his free time, becoming a mathematics teacher. By 1840, Holyoake was a lecturer at the Worcester Hall of Science. Best-known for coining the term “secularist,” Holyoake dedicated his life to freethought. He was sentenced to six months in jail for saying England was “too poor” to support a God and should consider retiring him. He founded and edited a number of freethought journals, including Reasoner (1846-50), Leader (1850) and Secular Review (1876).

Holyoake wrote more than 160 pamphlets and works, including the books Origin and Nature of Secularism (1896), his autobiography, Sixty Years of an Agitator’s Life (1892), and the two-volume Bygones Worth Remembering (1905). He was president of the British Secular Union for many years, and became the first chair of the Rationalist Press Association.

As an Owenite, Holyoake was an ardent reformer who put causes over personal gain, helped work for women’s rights, political and educational reform, and personally aided refugees fleeing persecution. Contemporary American agnostic Robert G. Ingersoll wrote on Aug. 8, 1888: “There is no man for whom I have greater respect, greater reverence, greater love, than George Jacob Holyoake.” (D. 1906)

"Free thought means fearless thought. It is not deterred by legal penalties, nor by spiritual consequences. Dissent from the Bible does not alarm the true investigator, who takes truth for authority not authority for truth.”

— Holyoake, "The Origin and Nature of Secularism" (1896)

Thomas Scott

On this date in 1808, Thomas Scott was born. Educated in France as a Catholic and independently wealthy, he served as a page at the court of Charles X. Scott became a rationalist as he approached the age of 40. From 1862 to 1877, he funded and distributed more than 200 pamphlets critical of religion, which were later compiled into 16 volumes. He wrote a few himself, but mainly published well-known freethinkers, such as Moncure Daniel Conway.

Scott disseminated his pamphlets to the clergy as well as the public. From his own printing house in Ramsgate, Scott published Jeremy Bentham‘s Church of England Catechism Examined and Hume‘s Dialogues on Natural Religion. According to Joseph McCabe, The English Life of Jesus (1872), which Scott published and bears Scott’s name, was actually written, at least in part, by the Rev. Sir G.W. Cox. (A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists) McCabe wrote that Scott “rendered a most valuable service to the cause in England.” (D. 1878)

Thomas Huxley

On this date in 1825, Thomas Henry Huxley was born in England. Huxley coined the term “agnostic” (although George Jacob Holyoake also claimed that honor). Huxley defined agnosticism as a method, “the essence of which lies in the rigorous application of a single principle … the axiom that every man should be able to give a reason for the faith that is in him.” Huxley elaborated: “In matters of the intellect, follow your reason as far as it will take you, without any other consideration. And negatively, in matters of the intellect do not pretend that conclusions are certain which are not demonstrated or demonstrable.” (From his essay “Agnosticism.”)

Huxley received his medical degree from Charing Cross School of Medicine, becoming a physiologist. He had spent his youth exploring science, especially zoology and anatomy, lecturing on natural history and writing for scientific publications. He was president of the Royal Society and was elected to the London School Board in 1870, where he championed a number of common-sense reforms.

Huxley earned the nickname “Darwin’s Bulldog” when he debated Darwin’s On the Origin of Species with Bishop Samuel Wilberforce in Oxford in 1860. When Wilberforce asked him which side of his family contained the ape, Huxley famously replied that he would prefer to descend from an ape than a human being who used his intellect “for the mere purpose of introducing ridicule into grave scientific discussion.”

Thereafter, Huxley devoted his time to the defense of science over religion. His essays included “Agnosticism and Christianity” (1889). His three rationalist grandsons were biologist Sir Julian Huxley, novelist Aldous Huxley and Henry Fielding Huxley, co-winner of a 1963 Nobel Prize. Huxley, appropriately, received the Darwin Medal in 1894. (D. 1895)

"Skepticism is the highest duty and blind faith the one unpardonable sin."

— Huxley, "Essays on Controversial Questions" (1889)

Ella E. Gibson

On this date in 1821, Ella Elvira Gibson was born in Winchendon, Mass. After teaching school, she married John Hobart in 1861. He was appointed chaplain of the Wisconsin 8th Volunteer Infantry Regiment and she worked alongside him before being appointed chaplain of the 1st Wisconsin Heavy Artillery Regiment after her 1864 ordination. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton refused to muster her because she was a woman. Despite that, she served at her post at Fort Lyon in Alexandria, Va., through the end of the war.

By an act of Congress in 1869, pay for her services was belatedly approved in the amount of $1,210. She did not receive her pension until 1876, then distributed most of it to freethought causes, which she had embraced soon after the war. She had divorced Hobart in 1868 and assumed her maiden name.

While serving, Gibson contracted malaria, which severely disabled her. Even when confined to bed, she wrote for nearly every freethought newspaper in the U.S. and edited “The Moralist” during the early 1890s. Her book The Godly Women of the Bible by an Ungodly Woman of the Nineteenth Century, the first such treatment of the bible, was published by The Truth Seeker Co. in the 1870s and was continuously in print for the next three decades.

She died at age 79 in Barre, Mass. No funeral was held and her remains were cremated. A hundred years later, a military appropriations bill in 2001 granted her the rank of captain in the Chaplains Corps of the U.S. Army. (D. 1901)

"The abominable laws respecting [women in the Bible] … are a disgrace to civilization and English literature; and any family which permits such a volume to lie on their parlor-table ought to be ostracized from all respectable society."

— Gibson, "The Godly Women of the Bible by an Ungodly Woman of the Nineteenth Century"

Robert Owen

On this date in 1771, reformer and philanthropist Robert Owen was born in Newtown, Wales. He became known as “a capitalist who became the first Socialist.” Owen started work as a clerk at age 9. With help from a sympathetic cloth merchant to whom he was apprenticed, Owen educated himself. He was an unbeliever by 14, influenced by Seneca, and his acquaintance with chemist John Dalton and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

By 18, Owen established a small spinning mill in Manchester. In 1799 he married Ann Dale, the daughter of a Glasgow cotton manufacturer, purchasing his father-in-law’s New Lanark mills in Scotland. Owen set out to put his humanitarian creed into practice and turned New Lanark into a model community attracting the attention of reformers around the world.

Owen set up the first infant school in Great Britain and a three-grade school for children under 10. He appealed to the government and other manufacturers to follow his lead but was rebuffed by clergy-led opposition when his views on religion became widely known. At an 1817 public meeting calling for “villages of unity and cooperation,” living wages and education of the poor at the City of London Tavern, Owen called “all religions” false.

He sought to limit hours for child labor in mills in 1815 and saw passage of a watered-down Factory Act in 1819. Owen’s Essays on the Principle of the Formation of Human Character (1816) were his major treatises, in which he advised, “Relieve the human mind from useless and superstitious restraints.”

He founded New Harmony, a model settlement in Indiana in 1825-28, a failed venture which he signed over to his sons Robert Dale and William Owen. Owen wrote Debate on the Evidences of Christianity (1829). Owen founded The Economist in 1821 to promote his progressive views and The New Moral World in 1834, along with an ethical movement called “Rational Religion.”

His “Halls of Science” attracted thousands of nonreligious followers (“Owenites”) and many trade unionists. An essay titled “Scientific Socialism: The Case of Robert Owen” by David Leopold describes the Halls of Science as:

“a base for ‘social missionaries’ and cultural and leisure activities for members (typically drawn from the best paid strata of the working class). By 1840 there were over sixty branches, with weekly events — including dances, concerts, lectures, and debates (all with a whiff of teetotalism) — ‘instituted to improve the habits and manners of the working classes, and more generally to cultivate kindly feeling and social fellowship among all classes.’ Owenite events sometimes shadowed the Christian calendar, with branches providing Owenite sermons and hymns on Sundays, and even Owenite rites for baptisms, marriages, and funerals.”

His autobiography was published in 1857-58. Joseph McCabe called him “the father of British reformers, and one of the highest-minded men Britain ever produced.” (Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists, 1920.) (D. 1858)

"Finding that no religion is based on facts and cannot therefore be true, I began to reflect what must be the condition of mankind trained from infancy to believe in errors."

— Owen, "Evidences of Christianity: A Debate with Alexander Campbell and Robert Owen" (1829)

Barbara Smoker

On this date in 1923, Barbara Smoker was born in Great Britain. Such a devout Roman Catholic that she considered becoming a nun, Smoker renounced religious faith at age 26 and became a secular humanist activist instead. She served as president of the National Secular Society (NSS), the most militant of the British secular groups, from 1971-96. Her script “Why I Am an Atheist” was recorded for the BBC in 1985. She fought a statutory ban on embryo research with a pamphlet, “Eggs Are Not People,” distributed to all members of Parliament in 1985.

In the tradition of 19th-century secular activists Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant, Smoker officiated at more than 400 humanist funerals, as well as at weddings and analogous ceremonies on behalf of the Gay and Lesbian Humanist Association, which she co-founded. Smoker served as chair of the Voluntary Euthanasia Society from 1981-85, editing Voluntary Euthanasia: Experts Debate the Right to Die (1986).

When Muslims held a London demonstration in May 1989 against Salman Rushdie, Smoker, holding a banner reading “Free Speech,” was attacked by a surge of demonstrators and was rescued by a police officer.

Smoker remained active in the NSS for the rest of her life. In 2019 she published her autobiography “My Godforsaken Life: Memoir of a Maverick.” She also received a lifetime achievement award from the NSS in 2019.Smoker remained active in the NSS for the rest of her life. In 2019 she published her autobiography “My Godforsaken Life: Memoir of a Maverick.” She also received a lifetime achievement award from the NSS in 2019.

She died at Lewisham Hospital at age 96. (D. 2020)

"People who believe in a divine creator, trying to live their lives in obedience to his supposed wishes and in expectation of a supposed eternal reward, are victims of the greatest confidence trick of all time."

— Smoker, "So You Believe in God!" (1974 pamphlet)

Alice Hubbard

On this date in 1861, Alice Hubbard (née Moore) was born. She was educated at State Normal School in Buffalo, New York, and the Emerson College of Oratory in Boston. She married Elbert Hubbard and became general superintendent of Hubbard’s Roycroft Shop, as well as manager of the Roycroft Inn and principal of Roycroft School for Boys. The couple espoused egalitarian marriage and feminism. Her husband, a freethinker like Alice, was a famous and respected writer particularly known for his aphorisms.

Alice Hubbard wrote several books, including Woman’s Work: Being an Inquiry and an Assumption (1908) and edited An American Bible (1912). In the introduction of that book, Alice wrote: “This is the book we offer — a book written by Americans, for Americans. It is a book without myth, miracle, mystery, or metaphysics — a commonsense book for people who prize commonsense as a divine heritage. The book that will benefit most is the one that inspires men to think and to act for themselves.”

Her chapters edit the writings of “the Prophets” (all of whom have biographical entries on this site): Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, Abraham Lincoln, Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson and her husband. The book is printed like a modern-day bible, in two-column script excerpting nuggets of wisdom from the selected American authors. The couple tragically went down on the Lusitania and lost their lives along with nearly 1,200 others. (D. 1915)

"The world can only be redeemed through action — movement — motion. Uncoerced, unbribed and unbought, humanity will move toward the light."

— Alice Hubbard's introduction to "An American Bible" (1912)

Joseph Lewis

On this date in 1889, Joseph Lewis was born in Montgomery, Ala., where he left school at age 9 to find employment. Self-educated, he read Robert G. Ingersoll and Thomas Paine, his lifelong “idol.” Moving to New York City in 1920, Lewis became president of Freethinkers of America. He started his own publishing house, the Freethought Press Association.

His many books include The Tyranny of God (1921), Lincoln, the Freethinker (1925), Jefferson, the Freethinker (1925), The Bible Unmasked (1926), Franklin, the Freethinker (1926), Burbank, the Infidel (1929), Atheism, a collection of his public addresses (1930), Voltaire, the Incomparable Infidel (1929), The Bible and the Public Schools (1931), Should Children Receive Religious Instruction? (1933), The Ten Commandments (1946), Thomas Paine, Author of the Declaration of Independence (1947) and In the Name of Humanity (1949), which condemned circumcision. His book An Atheist Manifesto, 1954, was his major treatise on freethought.

Lewis began publishing a bulletin, Freethinkers of America, in 1937, which was renamed Freethinker in the 1940s, and finally Age of Reason in the 1950s. Lewis persuaded the government of France to erect a sculpture of Paine by Gutzon Borglum (the Mount Rushmore sculptor) in Paris. Lewis also dedicated statues to Paine in Morristown, NJ., in 1950 and in front of Paine’s place of birth in Thetford, England, in 1964.

Lewis took numerous court cases to protect the separation of church and state, seeking punitive damages from New York’s Trinity Church when it erected a plaque with a bogus prayer by George Washington (Lewis lost). He protested the addition of “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance in 1954 and the issuance of Christmas stamps in the 1960s. Lewis broadcast freethought material over the radio when he lived in Miami, Florida. D. 1968.

“Atheism rises above creeds and puts Humanity upon one plane.

There can be no ‘chosen people’ in the Atheist philosophy.

There are no bended knees in Atheism;

No supplications, no prayers;

No sacrificial redemptions;

No ‘divine’ revelations;

No washing in the blood of the lamb;

No crusades, no massacres, no holy wars;

No heaven, no hell, no purgatory;

No silly rewards and no vindictive punishments;

No christs, and no saviors;

No devils, no ghosts and no gods.”— Lewis, "Atheist Rises Above Creeds," address on atheism at Community Church, New York City (April 20, 1930)

Ann Druyan

On this date in 1949, multi-talented author, popular science promoter, writer/producer and activist Ann Druyan was born in Queens, N.Y. Druyan was the longtime collaborator and spouse of astronomer Carl Sagan (until his death in 1996). The two science enthusiasts had two children together and co-wrote the best-sellers Comet (1985) and Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1992).

Sagan credited her as a contributor to his books Contact (1997), Pale Blue Dot (1997), The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark (1997) and Billions and Billions (posthumous, 1998), in which Druyan wrote the poignant epilogue addressing Sagan’s nonbelief and death.

Druyan co-wrote the Emmy and Peabody Award-winning television series “Cosmos,” viewed by half a billion in over 60 countries. She also wrote and produced the two updated “Cosmos” series: “A Spacetime Odyssey” hosted by Neil DeGrasse Tyson that aired on Fox and ran on The National Geographic Channel in 2014 and won multiple awards, including a Peabody; and “Cosmos: Possible Worlds,” also hosted by Tyson that debuted in 2019 on the same channels.

She served as creative director of the NASA Voyager Interstellar Record Project affixed to the Voyager I and II spacecrafts. Her articles have appeared in numerous publications, including The New York Times Sunday Magazine, Reader’s Digest, Parade, Discover and The Washington Post. She co-produced and co-created the hit film “Contact,” which starred an atheist-scientist heroine played by freethinker Jodie Foster.

Druyan produced and wrote the screenplay for “Comet,” a 3-D IMAX motion picture. Druyan, who has organized for peace and against nuclear testing, is founder and CEO of Cosmos Studios, served as secretary of the Federation of American Scientists, on the board of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws and directed the Children’s Health Fund. She was named Harvard’s Humanist of the Year in 2017.

Druyan has always made time to advocate for science and speak out against the illusion of religion. “By disobeying god, we escape from his totalitarian prison where you cannot ask any questions, where you must never question authority. We become our human selves,” Druyan wrote in The Skeptical Inquirer (November/December 2003).

She received FFRF’s 1997 Freethought Heroine Award. She told Freethought Radio in October 2006: “The Universe revealed by science is one of far more awesome grandeur than any religion has ever posited.”

“I don’t have any faith, but I have a lot of hope, and I have a lot of dreams of what we could do with our intelligence if we had the will and the leadership and the understanding of how we could take all of our intelligence and our resources and create a world for our kids that is hopeful.”

— The Skeptical Inquirer, "Ann Druyan Talks About Science, Religion, Wonder, Awe ... and Carl Sagan" (November/December 2003)

Wafa Sultan

On this date in 1958, Wafa Sultan was born in Banias, Syria. Sultan received her degree in medicine at the University of Aleppo, where she says she lost her faith in Islam after seeing one of her professors gunned down by the Muslim Brotherhood. In 1989 she and her husband emigrated to Los Angeles with their children.

Sultan has written essays critical of Islam, some published on the reform website Annaqed (The Critic). In 2005, Sultan gained notoriety for her appearance on Al Jazeera debating a Muslim cleric and asking, “Why does a young Muslim man, in the prime of life, with a full life ahead, go and blow himself up? In our countries, religion is the sole source of education and is the only spring from which that terrorist drank until his thirst was quenched.”

In 2009 she published her first book in English, A God Who Hates: The Courageous Woman Who Inflamed the Muslim World Speaks Out Against the Evils of Islam. She describes herself as a cultural Muslim. In 2006 she received FFRF’s Freethought Heroine Award.

“I receive too many emails from women in the Islamic world, telling me: ‘Go ahead, we are behind you,’ but unfortunately they’re afraid for their lives.”

— Sultan, speaking to FFRF's 2006 national convention

Elbert Hubbard

On this date in 1874, Elbert Hubbard was born in Bloomington, Illinois, the son of a country doctor. During his youth, the family moved to Buffalo, New York. Hubbard joined one of the first successful mail order businesses, JP Larkin of Buffalo, selling his interest in it at 36. After a trip abroad, he established Roycroft Printing Shop in East Aurora, New York, producing what are considered some of the finest handmade books of the 19th century, serving clients such as Henry Ford, Teddy Roosevelt and Queen Victoria.

Hubbard published several periodicals, including the monthly The Philistine (which printed his famous 1899 essay “A Message to Garcia”) and The Fra, also a monthly, with circulations that grew into the tens of thousands.

Hubbard, a firm freethinker, wrote eight books himself and produced a series, Little Journeys to the Homes of the Great (1895-1909), including one little book about Robert Green Ingersoll, the 19th century’s most well-known “infidel.” Gradually, Hubbard created a Roycroft community, including factory, blacksmith shop, farms, bank and an inn that is still standing. East Aurora today houses many of his artifacts in an Elbert Hubbard Museum. Hubbard became a popular lecturer and was hired as a columnist by Hearst Newspapers. He and his freethinking wife Alice Hubbard went down on the Lusitania to a watery grave on May 7, 1915. (D. 1915)

“When you once attribute effects to the will of a personal God, you have let in a lot of little gods and evils — then sprites, fairies, dryads, naiads, witches, ghosts and goblins, for your imagination is reeling, riotous, drunk, afloat on the flotsam of superstition. What you know then doesn’t count. You just believe, and the more you believe the more do you plume yourself that fear and faith are superior to science and seeing."

— Elbert Hubbard section, "An American Bible," edited by Alice Hubbard (1912)

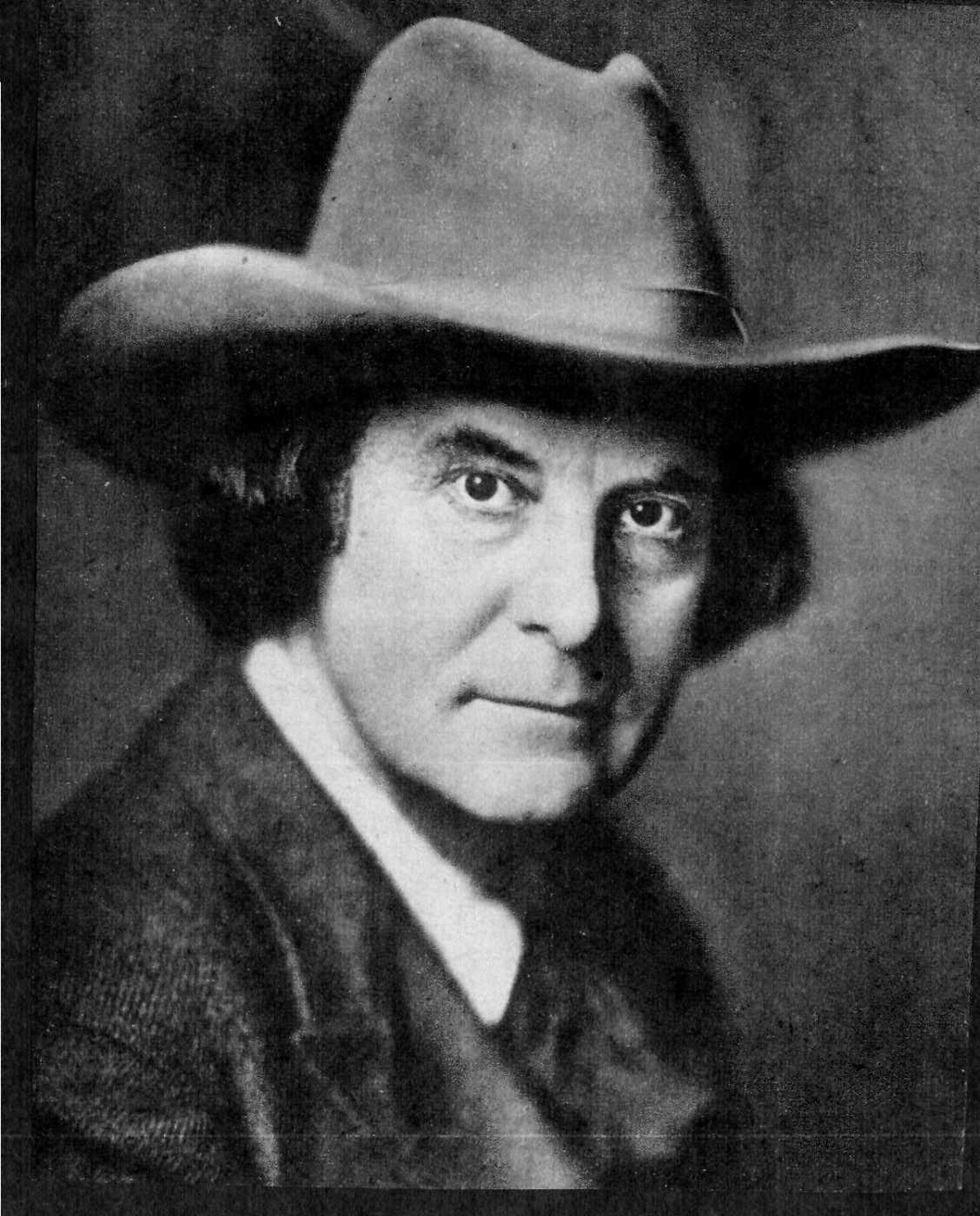

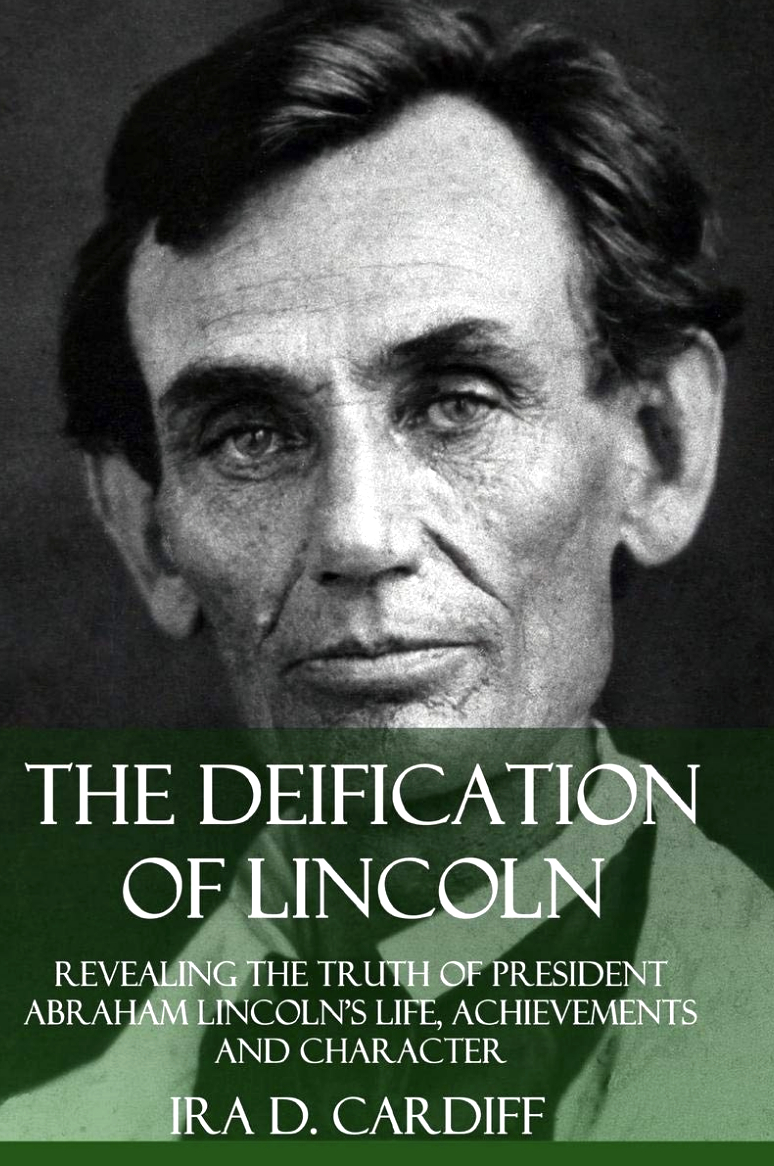

Ira Cardiff

On this date in 1873, botanist and humanist author Ira Detrich Cardiff was born. He directed the agriculture experimental station from 1914-17 at Washington State University, where he also headed the botany and plant physiology department. He later founded the Washington Dehydrated Foods Company in Yakima. In addition to academic publications, Cardiff wrote freethought articles, pamphlets and books, including The Deification of Lincoln (1943), What Great Men Think of Religion (1945), which focused on skeptics, and, as editor, The Wisdom of George Santayana. (D. 1964)

"What would Christ do about syphilis? Well, what should he do? Christ, being possessed of miraculous powers, why does he not obliterate syphilis from the face of the earth? Does Spirochaeta pallida, the organism causing syphilis, perform any useful function in the economy of nature? If not, why not obliterate it? Who is better equipped to do this than Jesus Christ?"

— Cardiff, "If Christ Came to New York," (undated pamphlet published in The Truth Seeker, c. 1930s)

Dan Barker

On this date in 1949, Dan Barker was born in California. His father, Norman Barker, a professional trombonist, played with Hoagy Carmichael and appeared in a cameo with Judy Garland in the movie “Easter Parade.” (See Norman with Garland starting at 12 seconds in this video clip.) More is here on his family background.

His mother, Patricia, was a talented amateur singer and the family often used music in their volunteer evangelism. Barker, who became a piano player and songwriter, worked as a volunteer missionary as a teenager, going to Mexico with youth groups and becoming fluent in Spanish.

He attended Asuza Pacific College, majoring in religion. Ordained by a Christian congregation, he worked as an assistant minister in several churches but mainly freelanced with a musical ministry, also writing secular children’s music. Many of his songs and two Christian children’s musicals were produced by Manna Music and other Christian publishing houses.

In his early 30s he started a course of reading in science, liberal theology and rationalism that led to “an intense inner conflict.” Finally, “I just lost faith in faith.” In 1983, he publicly left religion. He joined the staff of the Freedom From Religion Foundation in 1987, where he has served as public relations director, becoming co-president with his wife Annie Laurie Gaylor in 2004. FFRF published his book Losing Faith in Faith (1992), as well as three freethought/humanist books for children, including Just Pretend, and more than 70 freethought songs, including “You Can’t Win with Original Sin,” “None of the Above” and “Nothing Fails Like Prayer.” He collaborated with lyricist Charles Strouse on the song, “Poor Little Me.”

Barker has recorded his songs and other traditional and contemporary freethought music on three CDs for FFRF: “Friendly Neighborhood Atheist,” “Beware of Dogma” and “Adrift on a Star.” He also freelances as a busy keyboardist and piano player in Madison, Wis., performing jazz and the Great American Songbook, much of which he has discovered was written by secular songwriters.

He has participated in more than 100 public debates with Christian clergy, religious scholars and even an imam or two. His most recent books include Godless: How an Evangelical Preacher Became One of America’s Leading Atheists, foreword by Richard Dawkins (2008); The Good Atheist: Living a Purpose-Filled Life Without God, foreword by Julia Sweeney (2011); Life Driven Purpose: How an Atheist Finds Meaning, foreword by Daniel C. Dennett (2015); GOD: The Most Unpleasant Character in All Fiction, foreword by Dawkins (2016); Free Will Explained: How Science and Philosophy Converge to Create a Beautiful Illusion (2018); and Mere Morality (2018). Barker’s books are available here.

He has appeared on many national television talk shows, including “The Daily Show,” “The Phil Donahue Show,” “Oprah,” national Fox TV, ABC’s “Good Morning America,” “Religion & Ethics News Weekly” and “60 Minutes Australia.” He has co-hosted FFRF’s radio and TV shows and is a frequent speaker on college campuses and freethought conferences. He has four children from his first marriage and a daughter with Gaylor.

"I threw out the bath water, and there was no baby there."

— Dan Barker, "Losing Faith in Faith" (1992)

Paul Broca

On this date in 1824, Pierre Paul Broca was born in Sainte-Foy-la-Grande, France. He began attending medical school when he was only 17, graduated at 20 and later earned degrees in mathematics, literature and physics. Broca went on to become a professor of surgical pathology at the University of Paris and was an accomplished anatomist who advanced understanding of speech production in the brain. His most important achievement was discovering Broca’s area, a region of the brain responsible for speech production.

His work was also influential in cancer pathology and treatment of brain aneurysms. Broca founded the Anthropological Society of Paris in 1859, and his findings in anthropology often contradicted biblical teachings. Broca himself died, ironically, of a brain aneurysm. His brain was preserved after his death, becoming the inspiration for Carl Sagan’s 1974 book Broca’s Brain.

According to The End of the Soul by Jennifer Michael Hecht (2003), Broca thought that the more educated humans were, the less religious they would become. Broca also firmly supported natural selection: “Far from blushing in shame for my species because of its genealogy and parentage, I will be proud of all that evolution has accomplished.” (D. 1880)

"[Religion is] nothing more than a type of submission to authority."

— Broca, "Bulletins de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris"

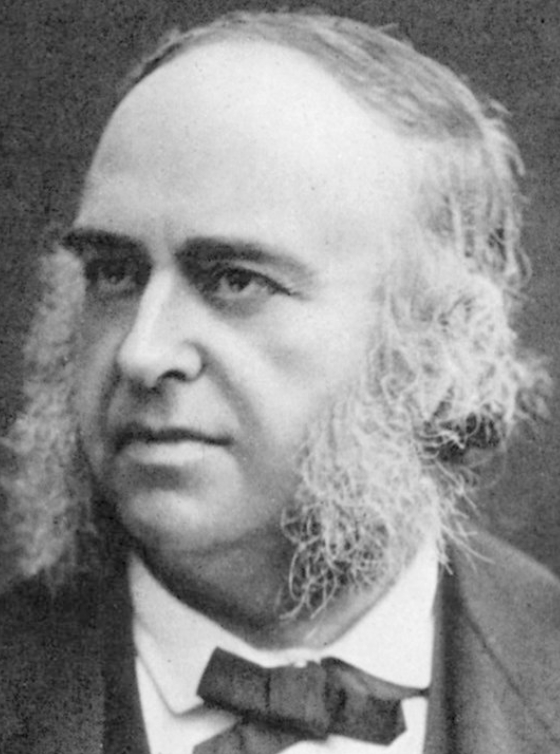

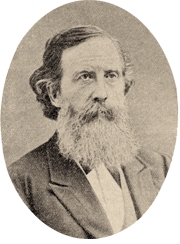

Benjamin Underwood

On this date in 1839, Benjamin Franklin Underwood was born in New York City, the second of seven children. Largely self-educated, he served in the Civil War and was imprisoned at Richmond after being wounded in the right leg. After being released through a prisoner exchange program, Underwood reinlisted and served through the war, receiving a commendation for bravery in action. After working as a reporter, lecturer and author, Underwood became a noted promoter of the theory of evolution.

He was appointed co-editor, with William J. Potter, of The Index in 1881, a weekly newspaper founded by a Unitarian. In 1887 he founded The Open Court in Chicago, a journal which published the writings of many freethinkers. Underwood wrote, lectured and debated as a major 19th-century advocate for the freethought movement. His books include The Influence of Christianity on Civilization (1871) and The Crimes and Cruelties of Christianity (1877). Underwood chaired the Congress of Evolution at the World’s Fair in Chicago in 1893. He was a supporter of feminism. His wife, Sara Underwood, published Heroines of Freethought in 1876. (D. 1914)

“There is no argument worthy of the name that will justify the union of the Christian religion with the State. Every consideration of justice and equality forbids it. Every argument in favor of free Republican institutions is equally an argument in favor of a complete divorce of the State from the Church."

— Underwood, "The Practical Separation of Church & State," an address to the 1876 Centennial Congress of Liberals

Josiah P. Mendum

On this date in 1811, Josiah P. Mendum was born in Kennebunk, Maine. In 1844, Mendum took over as editor and proprietor of the Boston Investigator, the first U.S. rationalist news publication, after Abner Kneeland retired. Under Mendum’s businesslike management, the newspaper became prosperous and influential. Mendum also republished books by Voltaire, D’Holbach, Volney and Paine. He lobbied hard for the building of a hall to memorialize Thomas Paine in 1870. By 1874, the Paine Memorial Hall was opened in Boston.

Mendum spent 40 years as rationalist advocate. He and Horace Seaver as co-editors were succeeded by Mendum’s son, Ernest Mendum, and by Lemuel K. Washburn. When J.P. Mendum died, a memorial was fittingly held at Paine Hall. Mendum was lauded for helping to turn “the strait-laced Boston of sixty years ago [into] the enlightened Hub of today … to ‘destroy bigotry and uproot the evils of superstition.’ ” (Boston Globe, Feb. 3, 1891) (D. 1891)

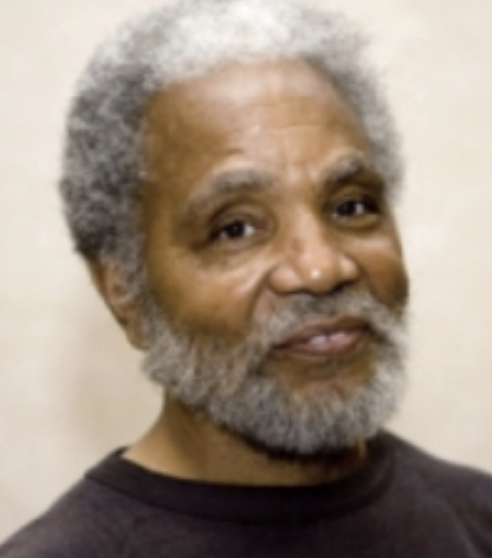

Ernie Chambers

On this date in 1937, politician Ernest Chambers, known as “the Maverick of Omaha” and “defender of the downtrodden,” was born in Omaha, Neb. Chambers understood early on the power of protest and of grassroots organizing, standing up for civil rights as a youth and emerging as a leader of African-American youths in Omaha. He graduated from Creighton University School of Law and was first elected to the unicameral legislature as a state senator in 1970, the only black member of the legislature in an overwhelmingly white, ultraconservative state.

Chambers became known for defending the rights of women, gays and lesbians and people of color. He challenged legislative prayers in the 1983 Supreme Court case Marsh v. Chambers, and although the court ruled against him, Chambers was successful in subsequently persuading the Senate to drop payment for prayers.

Rita Swan of Children’s Healthcare is a Legal Duty (CHILD) said in 2005, “Nebraska is the only state in the country that has never had a religious exemption to child neglect in either the juvenile or criminal codes and that distinction is due to Ernie’s forceful opposition and vigilance. Nebraska is one of four states without a religious exemption to metabolic screening of newborns and that again is because of Ernie’s leadership.” CHILD presented Chambers with its child advocacy service award for successfully arguing that “no parent should have a religious right to deprive a child of necessary health care” and keeping a religious exemption to health care from being enacted in that state.

Chambers cleverly filed a lawsuit in 2007 (Chambers v. God) to make a point about frivolous lawsuits. Chambers, who identifies as nonreligious without using a label, sought a permanent injunction against the defendant for making terroristic threats against him and his constituents, of inspiring fear and causing “widespread death, destruction and terrorization of millions upon millions of the Earth’s inhabitants.” In October 2008 the judge threw out his lawsuit, whimsically ruling that the defendant wasn’t properly served due to his unlisted home address.

Chambers, accepting FFRF’s Hero of the First Amendment Award in 2005, commented, “What I would do, from time to time, is mock, taunt, and ridicule my colleagues for injecting religion and Jesus into the legislature.” His political opponents, in a successful effort to finally unseat him from the Senate when they could not do so electorally, passed a law in 2000 establishing term limits so he was unable to seek reelection in 2008. He was reelected in 2012 and 2016 to four-year terms. In 2015, FFRF awarded Chambers its Emperor Has No Clothes Award.

“As an elected official, I know the difference between theology and politics. My interest is in legislation, not salvation.”

— Chambers, Hero of the First Amendment acceptance speech (Nov. 12, 2005)

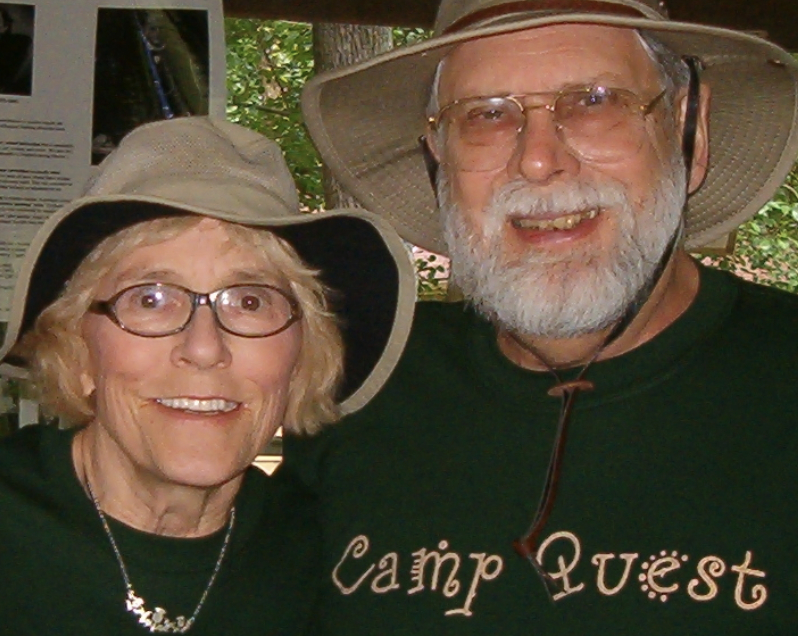

Fred Edwords

On this date in 1948, humanist leader Fred Edwords was born in San Diego. He has dedicated his life to advocating for the atheist, agnostic, secular, humanist and freethinking communities. In the late 1960s he attended San Diego City College and the Bill Wade School of Radio and Television, going on to work as a radio newscaster and then as an underground filmmaker. Edwords directed the United Coalition of Reason, which was founded in 2009 and works to promote the community of reason and separation of church and state.

Edwords worked for the American Humanist Association for over 20 years, serving as executive director and then as editor of The Humanist, the organization’s magazine. He was president of Camp Quest, a children’s summer camp that promotes reason, critical thinking and other ideas embraced by the humanist and secular movements. The camp’s motto is, “Camp Quest. It’s beyond belief!” He and Mary Caroll Murchison married in 1980 and have two daughters.

PHOTO: American Humanist Association photo under CC 3.0.

“Much of human progress has been in defiance of religion or of the apparent natural order. The defiance of religious and secular authority has led to democracy, human rights, and the protection of the environment. Humanists make no apologies for this. Humanists twist no biblical doctrine to justify such actions.”

— Edwords, "What is Humanism?" (1989, retrieved from the American Humanist Association website)

E. Haldeman-Julius

On this date in 1889, Emanuel Julius, later known as E. Haldeman-Julius, was born in Philadelphia, the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants. An early socialist, he educated himself at party headquarters, reading tracts on freethought, philosophy and economics. In 1906 he left home for good, heading for New York City. His self-education continued when a sympathetic librarian at a girls’ school in Tarrytown, where he had found work, introduced him to visiting dignitary Mark Twain. Emanuel’s first attributed article, “Mark Twain: Radical,” was published in a socialist periodical in 1910.

He worked for a variety of socialist newspapers, including New York Evening Call, Coming Nation, published in Girard, Kansas, the Milwaukee Leader, and the Chicago Evening World. He became editor and briefly acquired the Western Comrade, published in Los Angeles. He met his wife-to-be, Marcet Haldeman, an actress and heiress, in New York City and followed her home to Girard, Kansas. There he worked for Appeal to Reason, the largest socialist weekly in the country. They married in 1916 and legally combined their surnames at the urging of Marcet’s aunt, Jane Addams of Hull House fame. They had two daughters and a son. Haldeman-Julius, with his wife’s help, purchased Appeal to Reason and its publishing plant in 1918.

By the following year he had initiated his People’s Pocket Series — inexpensive paperbacks later renamed Little Blue Books, to match their appearance. Haldeman-Julius reprinted classics, socialist, radical and freethought literature. Most of the paperbacks contained a bonus page of his trademark nonreligious views. He also published a variety of periodicals, including American Freeman. In 1925 he launched the Big Blue Books series, publishing such notable authors as Bertrand Russell and Joseph McCabe.

Haldeman-Julius revolutionized the publishing industry, bringing avant-garde authors to the masses. His radical politics, including attacks against President Herbert Hoover, brought him to the attention of the FBI, which he in turn pilloried in print. He further alienated the status quo by publishing McCabe’s allegations of Vatican collaboration with the Axis during World War II. J. Edgar Hoover’s 20-year investigation of the publisher resulted in a verdict of tax evasion in 1951. Haldeman-Julius appealed the verdict but was found drowned in his swimming pool later that year. (D. 1951)

"It is natural that people should differ most, and most violently, about the unknowable. … There is all the room in the world for divergence of opinion about something that, so far as we can realistically perceive, does not exist."

— Haldeman-Julius, "The Unknowable," The Militant Atheist

Anthony Collins

On this date in 1676, Anthony Collins, called the “Goliath of freethinking” by Thomas Huxley, was born in Heston, England. Collins studied at Eton and King’s College, Cambridge, and was a close friend of John Locke. He moved in a circle of leading freethinkers, including John Toland and Matthew Tindal. “An Essay Concerning the Use of Reason” was published (anonymously) in 1707, along with a letter addressing immateriality and the soul. A debate in 1708 with Samuel Clarke resulted in the publication of four pamphlets by each participant.

In 1710 Collins wrote “Vindication of the Divine Attributes, in Some Remarks on Archbishop (King’s) Sermon.” The 1713 book, A Discourse of Freethinking, was his most influential work, helping to popularize the term “freethought.” Philosophical Inquiry Concerning Human Liberty, published in 1717, won the praise of Voltaire. The Grounds and Reasons of the Christian Religion (1724) rejected the claim that Jesus fulfilled Old Testament prophecies. Although Collins left England for a time when debate heated up after the publication of A Discourse of Freethinking, the courteous scholar was taken most seriously by leading religionists and Anglicans.

Grounds, with its serious arguments against prophecy and its advancement of the scientific principle, provoked more than 30 books and essays by religionists trying to counter it. Collins is best described as a deist and materialist who opposed “priestcraft,” although he did differentiate between good and bad priests. He willed his unpublished manuscripts to Pierre Desmaizeaux, who sold them after Collins’ death in 1729 to his widow. It appears that she then destroyed them. Desmaizeaux quickly regretted his decision but it was too late. (D. 1729)

"The Use of the Understanding, in endeavouring to find out the Meaning of any Proposition whatsoever, in considering the nature and Evidence for or against it, and in judging of it according to the seeming Force or Weakness of the Evidence."

— Collins' definition of freethought, "Discourse of Freethinking" (1713)

Samuel Porter Putnam

On this date in 1838, Samuel Porter Putnam, the son of a Congregationalist minister, was born in New Hampshire. He became a student at Dartmouth in 1858 and enlisted as a private in the Civil War, where, after two years of service he was promoted to captain. He became a Congregationalist minister in 1868 after three years at the Chicago Theological Seminary. Three years later he broke with that denomination and joined the Unitarians. After serving in various congregations, he then “gave up all relations whatsoever with the Christian religion, and became an open and avowed Freethinker,” as he recorded in his 1894 opus Four Hundred Years of Freethought.

During the Rutherford B. Hayes administration he was appointed to the Civil Service. He left that work in 1887 to head the American Secular Union. He was elected president of the California State Liberal Union in 1891 and the Freethought Federation of America in 1892. He noted that he visited all but four of the states and territories in his work for freethought, traveling more than 100,000 miles. His other writings include: Prometheus, Gottlieb: His Life, Golden Throne, Waifs and Wanderings, Ingersoll and Jesus, Why Don’t He Lend a Hand? Adami and Heva, The New God, The Problem of the Universe, My Religious Experience, Religion a Curse, Religion a Disease, Religion a Life, and Pen Pictures of the World’s Fair.

Putnam’s tragic death created a mild scandal. He and a young lecturer colleague, May Collins, had been touring in Boston. They returned after dinner to the home where Collins was staying and were found dead the next morning in her room, victims of leaking gas. Although they were fully clothed, and there was no “evidence of impropriety,” the religious press attacked Putnam, disclosing that he was a divorced man with two children. (D. 1896)

"The last superstition of the human mind is the superstition that religion in itself is a good thing, though it might be free from dogma. I believe, however, that the religious feeling, as feeling, is wrong, and the civilized man will have nothing to do with it”

— Putnam, "My Religious Experience" (1891)

Vern Bullough