journalists

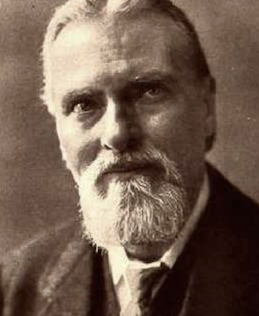

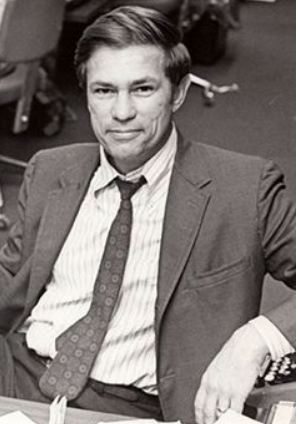

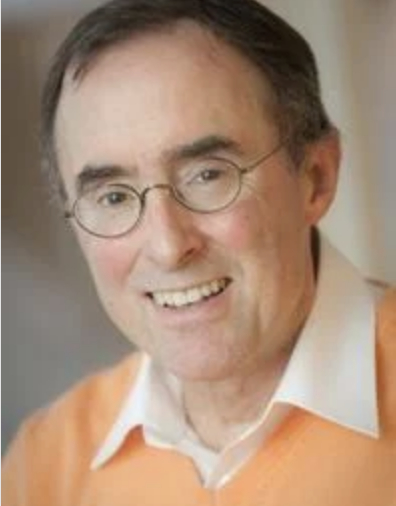

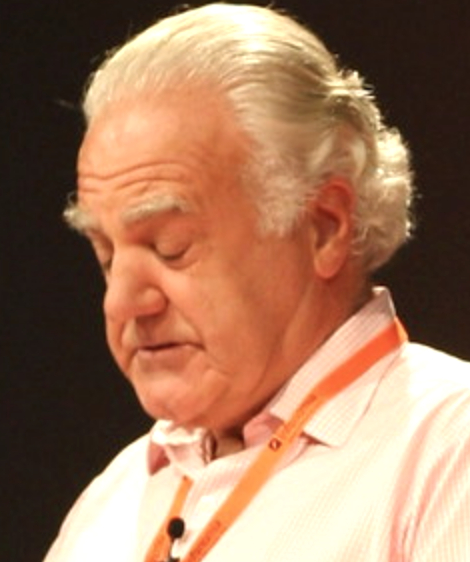

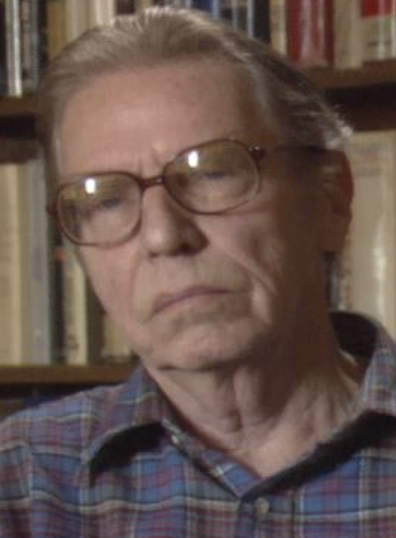

Lewis Lapham

On this date in 1935, Lewis Henry Lapham was born in San Francisco. He earned his bachelor’s degree in history from Yale University in 1956 and attended Cambridge University (1956–57). After graduation he worked as a reporter for the San Francisco Examiner (1957-60) and at age 25 became the U.N. correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune (1960-62). He later became managing editor of the prominent literary journal Harper’s Magazine (1971-75) and was soon appointed its editor (1976-2006).

He was a prolific journalist who wrote articles for many publications, including The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. In 2007, Lapham founded and became editor of Lapham’s Quarterly, a history magazine. His many books included Waiting for the Barbarians (1998) and Gag Rule: On the Suppression of Dissent and the Stifling of Democracy (2005).

Lapham was also the host of the television show “Bookmark” (1988-91). He received the 1994 and 1995 National Magazine Awards for his journalistic contributions to Harper’s. In 2007, Lapham was included in the American Society of Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame. He married Joan Brooke Reaves in 1972 and they had three children: Anthony, Elizabeth and Winston. Andrew married the daughter of former Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney.

“As an unbaptized child raised in a family unaffiliated with the teachings of a church, I missed the explanation as to why the stories about Moses and Jesus were to be taken as true while those about Apollo and Rumpelstiltskin were not,” Lapham wrote of his lifelong nonbelief in “Mandates of Heaven,” the introduction to the Winter 2010 issue of Laphams Quarterly.

He continued: “[French philosopher Michel] Onfray observes that ‘a fiction does not die, an illusion never passes away,’ situating Yahwey, together with Ulysses, Allah, Lancelot of the Lake, and Gitche Manitou, among the immortals sustained on the life-support systems of poetry and the high approval ratings awarded to magicians pulling rabbits out of hats.”

He expressed his disdain for the intersection of church and state in America, saying, “The dominant trait in the national character is the longing for transcendence and the belief in what isn’t there — the promise of the sweet hereafter that sells subprime mortgages in Florida and corporate skyboxes in heaven.” He died in Rome at age 89. (D. 2024)

PHOTO: By Terry Ballard under CC 2.0.

"God is the greatest of man's inventions, and we are an inventive people, shaping the tools that in turn shape us, and we have at hand the technology to tell a new story congruent with the picture of the earth as seen from space instead of the one drawn on the maps available to the prophets wandering the roads of the early Roman Empire."

— Lewis Lapham, Lapham's Quarterly (Winter 2010)

Linda Greenhouse

On this date in 1947, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Linda Greenhouse, a staunch advocate of state-church separation, was born in New York City to H. Robert Greenhouse, a physician, and Dorothy Greenlick Greenhouse, a 1941 graduate of Hunter College. She grew up in Hamden, Conn., later earning a B.A. in government while graduating magna cum laude in 1968 from Radcliffe College, where she was an editor at the Harvard Crimson, worked as a stringer for the Boston Herald and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa.

She joined The New York Times in 1968 as a news clerk to columnist James Reston, then worked as a reporter and Capitol bureau chief covering the legislature in Albany. After a year at Yale Law School, where she earned a master of studies in law degree in 1978, Greenhouse joined the Times’ Washington staff and started a 30-year career reporting on the U.S. Supreme Court.

She won the Pulitzer Prize for Beat Reporting in 1998, the American Political Science Association’s 2002 Carey McWilliams Award for “a major journalistic contribution to our understanding of politics” and the 2004 Goldsmith Career Award for Excellence in Journalism from Harvard University’s Kennedy School. Accepting a Radcliffe Institute Medalist award in 2006, she decried “the sustained assault on women’s reproductive freedom and the hijacking of public policy by religious fundamentalism.”

She ended her tenure as a reporter at the Times in 2008 while continuing to write a biweekly op-ed column on law as a contributing columnist. As of this writing, Greenhouse is the Joseph Goldstein Lecturer in Law and Knight Distinguished Journalist in Residence at Yale Law School and president of the American Philosophical Society. Her husband, Eugene Fidell, is the Florence Rogatz Lecturer in Law at Yale, and their daughter Hannah is a filmmaker in Los Angeles.

Her books include Becoming Justice Blackmun: Harry Blackmun’s Supreme Court Journey (2005), Before Roe v. Wade: Voices That Shaped the Abortion Debate Before the Supreme Court’s Ruling (with Reva Siegel, 2011), The U.S. Supreme Court: A Very Short Introduction (2012), The Burger Court and the Rise of the Judicial Right (with Michael Graetz, 2016) and Just a Journalist: Reflections on the Press, Life, and the Spaces Between (2017).

Greenhouse, speaking at FFRF’s 33rd national convention in October 2010 in Madison, Wis., said she admires the foundation’s work and always finds briefs filed by its attorneys “refreshing and very enlightening.” Her speech addressed “Monumental questions” before the Supreme Court.

“[I]t's past time for the rest of us to step back and consider the impact of religion's current grip on public policy — not only on the right to abortion, but on the availability of insurance coverage for contraception in employer-sponsored health plans and on the right of gay and transgender individuals to obtain medical services without encountering discrimination.”

— Greenhouse, "Let's Not Forget the Establishment Clause," The New York Times (May 23, 2019)

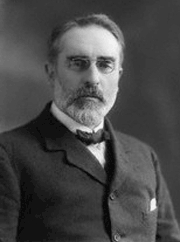

G.W. Foote

On this date in 1850, atheist activist George William Foote was born in England. In 1876 he began co-editing a weekly newspaper, The Secularist, with Jacob Holyoake, then became the first editor of the National Secular Society’s publication The Freethinker. Foote edited The Freethinker for 35 years. The magazine is still published but moved to online-only in 2014.

Foote was prosecuted for blasphemy in 1882 and jailed for a year. His plight brought reform, making future criticism of Christianity lawful in Great Britain. Foote launched several other freethought journals, publishing companies and presses, devoting his life and career to the advancement of secularism. His books include Flowers of Freethought and, with W.P. Ball, The Bible Handbook. (D. 1915)

"Who burnt heretics? Who roasted or drowned millions of ‘witches’? Who built dungeons and filled them? Who brought forth cries of agony from honest men and women that rang to the tingling stars? Who burnt Bruno? Who spat filth over the graves of Paine and Voltaire? The answer is one word — Christians."

— Foote from "Are Atheists Wicked?" (a chapter in "Flowers of Freethought," 1894)

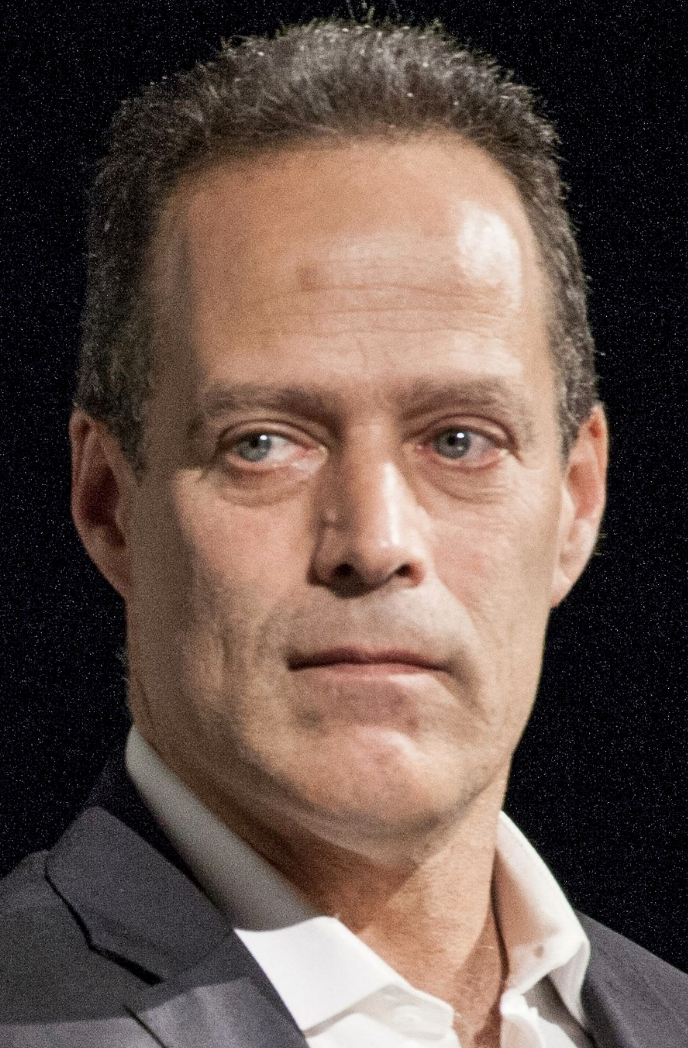

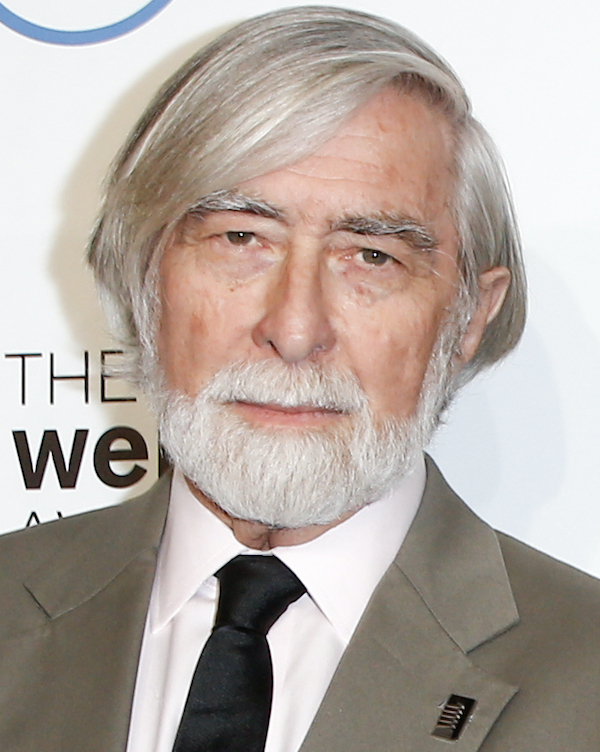

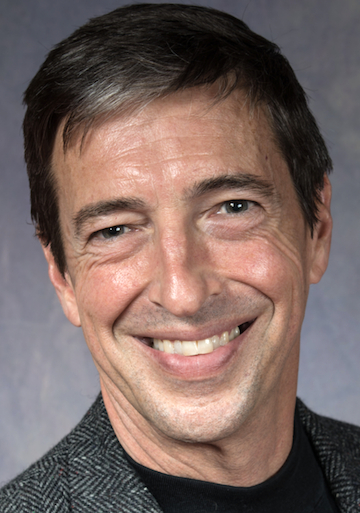

Andy Rooney

On this date in 1919, commentator Andrew Aitken “Andy” Rooney was born in Albany, N.Y. After high school, he attended Colgate University until he was drafted into the U.S.Army in 1941. He was one of six correspondents who flew with the Eighth Air Force making the first U.S. bombing raids over Germany. He joined CBS in 1949 and helped write for the popular “Garry Moore Show” (1956-65), while also writing for CBS News public affairs. He collaborated with Harry Reasoner on a series of news specials from 1962-68.

Rooney won the first of his three Emmy Awards for his special “Black History: Lost, Stolen or Strayed” (1968). Starting in 1979, he wrote a regular column for Tribune Media Services. “A Few Minutes with Andy Rooney” debuted on the TV news program “60 Minutes” in July 1978 with an essay about misleading reporting of auto fatalities on the Independence Day weekend. Rooney delivered 800 on-air essays for “60 Minutes.”

The latest of his 13 books was Years of Minutes. In his 1999 book “Sincerely, Andy Rooney,” he included a final section called “Faith in Reason,” in which he reprinted a letter to his children about his agnosticism and freethought views.

He was a recipient of FFRF’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award in 2001 for speaking the plain truth about religion as a public figure. He referred to himself as “a writer who appears on television,” and was also awarded a Lifetime Achievement Emmy and the Ernie Pyle Lifetime Achievement Award. Rooney appeared regularly on “60 Minutes” until five weeks before his death at age 92 in New York City. (D. 2011)

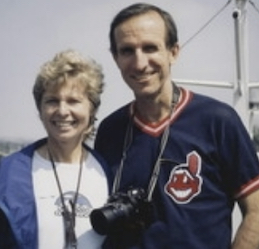

PHOTO: Rooney in 1991 at the Kennedy Center Honors in Washington; photo by Shutterstock/Mark Reinstein.

"We all ought to understand we’re on our own. Believing in Santa Claus doesn’t do kids any harm for a few years but it isn’t smart for them to continue waiting all their lives for him to come down the chimney with something wonderful. Santa Claus and God are cousins.”

“Christians talk as though goodness was their idea but good behavior doesn’t have any religious origin. Our prisons are filled with the devout.”

“I’d be more willing to accept religion, even if I didn’t believe it, if I thought it made people nicer to each other but I don’t think it does."

— From a section titled "Faith in Reason" in his book "Sincerely, Andy Rooney" (1999)

Sebastian Junger

On this date in 1962, journalist and filmmaker Sebastian Junger was born in Belmont, Mass., to painter Ellen Sinclair and physicist Miguel Chapero Junger, who emigrated to the U.S. from Germany in 1941 because of his paternal Jewish ancestry. The younger Junger said he was raised in “a very rational household.” In a 2016 New York Times interview, he said, “I grew up with parents who were essentially antireligious, and so I never attended church. John Stuart Mill’s ‘Utilitarianism’ gave me the kind of ethical guidance that every person needs — religious or otherwise.” He studied cultural anthropology in Connecticut at Wesleyan University, which became independent of the Methodist Church in 1937, and graduated in 1984.

He started working as a freelance journalist while taking other jobs to support himself, later successfully selling pieces to publications like Harper’s, The New York Times Magazine, Vanity Fair, National Geographic Adventure, Outside and Men’s Journal. Researching hazardous jobs like commercial fishing led to his first book, The Perfect Storm: A True Story of Men Against the Sea (1997), which became a bestseller and a movie in 2000 starring George Clooney and Mark Wahlberg. Fire (2001) was a nonfiction collection about more dangerous pursuits — diamond mining, firefighting, peacekeeping in Kosovo and guerrilla warfare in Afghanistan. The previous year he had received a National Magazine Award for his Vanity Fair piece “The Forensics of War.” He received the 2007 Winship/PEN Award for A Death in Belmont, a book about the 1963 rape and murder of Bessie Goldberg.

He and British photographer Tim Hetherington teamed up on the award-winning “The Other War: Afghanistan,” shown on ABC’s “Nightline” in 2008. Junger’s book War (2010) revolved around a U.S. Army airborne platoon in Afghanistan. He and Hetherington co-directed a related documentary film, “Restrepo,” nominated for a 2009 Academy Award. Three documentaries about war and its aftermath followed: “Which Way Is The Front Line From Here?” (2013, about Hetherington’s 2011 death while covering the Libyan civil war), “Korengal” (2014) and “The Last Patrol” (also 2014). Another book was published in 2016, Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging.

Hetherington’s death made Junger question his own willingness to put himself in harm’s way to get the story and helped him decide he’d had enough. “I suddenly was realizing the effect of Tim’s death on everyone he loved, including me, and I just didn’t want to risk doing that to everyone I love.” (Cultist, 2013.) During a 2014 ethics panel discussion hosted by the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, he was asked if he was an atheist in a foxhole and answered, “As an atheist, I think about that phrase and I think, what is it really about an artillery bombardment that leads you to the conclusion that God is involved in this? I really see it the other way around: Clearly, God has nothing to do with what’s going on today.” Asked a similar question in a 2016 C-SPAN2 interview about there being no atheists in foxholes, he said, “I know empirically that’s not true.”

Junger married Daniela Petrova in 2002. They divorced in 2014. As of this writing, he lives in New York City and Cape Cod, Mass.

PHOTO: U.S. National Archives, public domain photo, 2013

“The reason I think I am an atheist is because I haven’t encountered a tangible reason to believe in God.”

— Sebastian Junger interview, C-SPAN2 "Book TV" (July 3, 2016)

A.A. Milne

On this date in 1882, classic children’s author Alan Alexander Milne, known as A.A. Milne, was born in England and brought up in London. With his brothers he attended his schoolteacher father’s school, Henley House. One of his influential teachers there was H.G. Wells. Attending Cambridge on a mathematics scholarship, Milne was given the gift of 1,000 pounds by his father upon graduation. He used it to move back to London and become a writer.

Milne freelanced for newspapers, joined the staff of Punch magazine and wrote a book that flopped, Lovers in London. In 1913 he married Dorothy “Daphne” de Sélincourt. In 1915 he volunteered in World War I and wrote his first play while serving. His only child, Christopher Robin, was born in 1920. In his 1974 book The Enchanted Places, Christopher wrote about being estranged from his parents and resenting what he came to see as his father’s exploitation of his childhood.

In his obituary in 1996, The Observer wrote: “Christopher Robin, a ‘sweet and decent’ man who overcame a childhood in which he was haunted by Pooh and taunted by peers, has left without saying his prayers – he was a dedicated atheist – aged 75.”

Milne’s When We Were Young was published in 1924, followed by Winnie the Pooh (1926), The House at Pooh Corner (1926) and Now We Are Six (1927). Milne subsequently wrote several plays, a detective novel and, in 1952, Year In, Year Out. (D. 1956)

PHOTO: Milne and Christopher Robin in 1926.

"The Old Testament is responsible for more atheism, agnosticism, disbelief — call it what you will — than any book ever written; it has emptied more churches than all the counter-attractions of cinema, motor bicycle and golf course."

— A.A. Milne, cited in "2000 Years of Disbelief" by James A. Haught (1996)

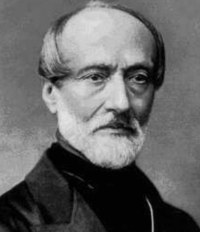

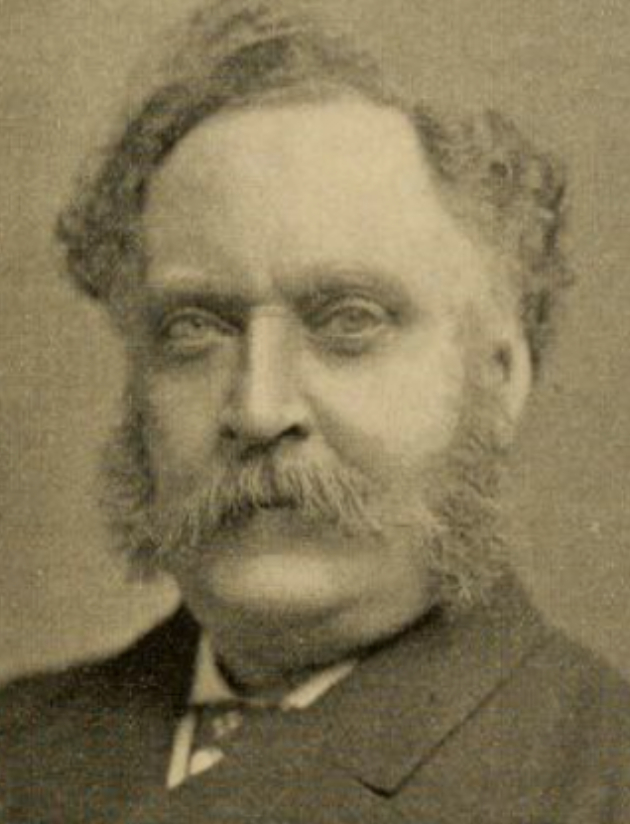

Joseph Mazzini Wheeler

On this date in 1850, Joseph Mazzini Wheeler was born in Great Britain. Wheeler, an atheist, is best known as the author of the monumental Biographical Dictionary of Freethinkers (1889). Wheeler, who dedicated his life to freethought after moving to London in the early 1870s, was a close friend of freethought editor G.W. Foote. Wheeler also wrote Frauds and Follies of the Fathers (1888), Footsteps of the Past (1895) and co-authored Crimes of Christianity with Foote.

He served for many years as vice president of the National Secular Society and was a frequent contributor to freethought periodicals. He served as subeditor of the National Secular Society’s publication The Freethinker from its founding in 1881 to his death at age 48. (D. 1898)

"The merits and services of Christianity have been industriously extolled by its hired advocates. Every Sunday its praises are sounded from myriads of pulpits. It enjoys the prestige of an ancient establishment and the comprehensive support of the State. It has the ear of rulers and the control of education. Every generation is suborned in its favor. Those who dissent from it are losers, those who oppose it are ostracised; while in the past, for century after century, it has replied to criticism with imprisonment, and to scepticism with the dungeon and the stake."

— from "Crimes of Christianity" by J.M. Wheeler and G.W. Foote (1887)

Robin Morgan

On this date in 1941, Robin Morgan — feminist author, journalist, editor, lecturer, organizer, atheist and activist — was born in New York City. As she notes in her memoir, Saturday’s Child, “Saturday’s child has to work for a living.” She started at age 2 as a tot model. She had her own radio show by age 4, then acted in the role of Dagmar on the popular series “Mama” in the 1940s and 1950s. She left show biz to write and became a founder and leader of the contemporary feminist movement.

Morgan’s columns and articles for Ms. magazine appeared from 1974-88. She was editor-in-chief of Ms. for four years and later its international consulting editor. Her groundbreaking anthology Sisterhood Is Powerful came out in 1972, followed by Sisterhood Is Global (1984), Sisterhood Is Forever (2003) and Fighting Words: A Toolkit for Combating the Religious Right (2006). Morgan is a distinguished poet and the author of more than 20 books, including her 2006 novel The Burning Time, based on the first witchcraft trial in Ireland.

She has traveled the globe as a feminist activist, scholar, journalist and lecturer. She is a co-founder of the Feminist Women’s Health Network, the Feminist Writers’ Guild, Media Women and the National Network of Rape Crisis Centers. Her timely The Demon Lover: On the Sexuality of Terrorism tells the personal story of her travel to refugee camps in the Middle East, with a post-9/11 introduction and afterword. A recipient of many awards, she was named FFRF’s Freethought Heroine in 2005 and is an honorary director.

She was married from 1962-83 to poet Kenneth Pitchford, a founding member of the Effeminist movement. He and Morgan, who are both bisexual, have a son, musician Blake Morgan.

She was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2010. Instead of curtailing her effectiveness, the diagnosis inspired her to take the lead in creating the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation’s Women and PD Initiative to help women be better served by research, treatment and assistance for their caregivers. Morgan has shared her struggle with the disease by writing and presenting about her experiences at a variety of venues, including her 2015 Ted Talk, viewed over a million times. In 2018 she published Dark Matter: New Poems, which includes the verses from that presentation.

“Religion is not about awe and joy, despite its purported proprietorship of these and its promise to eventually deliver what already lies around us every day, freely available for utter celebration. Religion is about something else. The etymology of the word itself, from the Latin, to being ‘bound by rules.’ Religion is about terror.”

— Freethought Heroine acceptance speech at FFRF's national convention (Nov. 11, 2005)

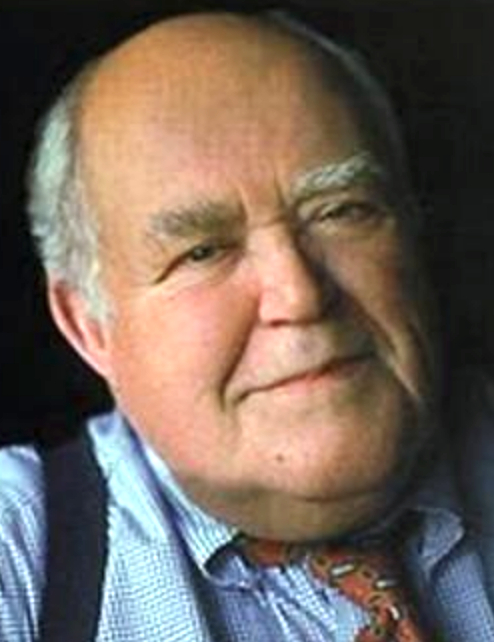

Jack Germond

On this date in 1928, journalist John Worthen “Jack” Germond was born in Newton, Mass. Germond wrote several books, mainly focusing on politics. After serving in the U.S. Army in 1946-47, he earned a B.A. and B.S. from the University of Missouri. He graduated in 1951 and began writing for the Rochester, N.Y., Times-Union, eventually heading its Washington bureau. He was the Washington Star’s political editor from 1974-81 and wrote a syndicated column on national politics for 24 years with fellow journalist Jules Witcover.

He moved to the Baltimore Sun when the Star folded. He first appeared on NBC’s “Meet the Press” in 1972 and “The Today Show” in 1980 and on PBS’ “The McLaughlin Group” in 1981. Germond tended to be liberal politically and was seen by many as in touch with the average American and as a traditional “old-school” newspaper reporter.

His books included Fat Man Fed Up: How American Politics Went Bad (2005), Fat Man in the Middle Seat: Forty Years of Covering Politics (2002), Mad as Hell: Revolt at the Ballot Box, 1992 (1994), Whose Broad Stripes and Bright Stars? (1989) and Blue Smoke and Mirrors: How Reagan Won and Why Carter Lost the Election of 1980 (1981). He co-wrote his earlier books with Witcover. He had two daughters with his first wife, Barbara Wipple. Their daughter Mandy died at age 14 from leukemia. After a 1988 divorce he married Alice Travis, a Democratic Party official and political activist. (D. 2013)

“In the interests of full disclosure, I must note that although I was brought up as a Protestant, I have been an atheist my entire adult life. I do not proselytize, however. Nor do I question the faith of others. I just don’t want to be obliged to accept someone else’s faith as a factor in my government. If John Ashcroft wants to hold a prayer meeting and advertise his piety, let him find someplace besides the Justice Department.”

— Jack Germond, "Fat Man Fed Up" (2005)

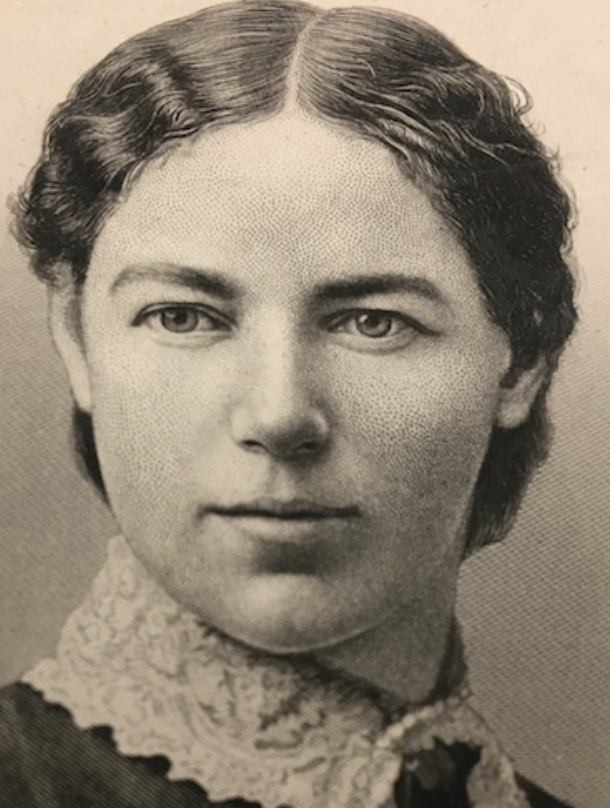

Eugene M. MacDonald

On this date in 1855, Eugene Montague MacDonald was born. The American journalist became a foreman at The Truth Seeker, a 19th-century freethought newspaper. When Truth Seeker founder D.M. Bennett died, MacDonald and two others established The Truth Seeker Company, buying the newspaper in 1883. MacDonald edited the 19th century’s leading freethought publication for 26 years. His brother George took over editorship when Eugene retired shortly before his death. Truth Seeker readers and contributors included Clarence Darrow, who wrote in 1931 that he had been connected with the publication for 50 years. (D. 1909)

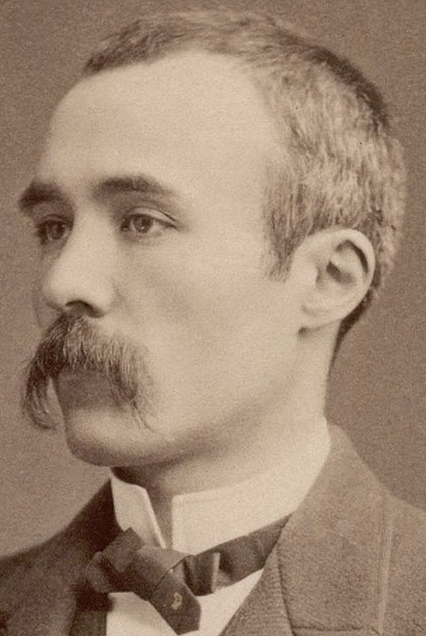

PHOTO: MacDonald, c. 1883.

"The Chicago World’s Fair having been decreed, the kind of church people who adopt meddling as a means of grace saw that now was their day of salvation. Hitherto, with their fussy restrictions on Sunday work and amusements, they had been obliged to function merely as local nuisances. Now they would close the World’s Fair on Sunday and make themselves felt as pests by all nations.”

— From The Truth Seeker, 1892, cited in "Fifty Years of Freethought, Vol. II" by George MacDonald (1929)

Lydia Maria Child

On this date in 1802, Lydia Maria Child (née Francis) was born in Medford, Mass. Considered one of the first U.S. “women of letters,” she became a famous abolitionist, author, novelist and journalist. Her poem “Over the River and Through the Wood” (originally titled “A Boy’s Thanksgiving Day”) became popular as a song: “Over the river and through the wood / to grandfather’s house we go.” After her mother died when she was 12, she went to live with her older married sister in Maine and studied to become a teacher.

She ran a private school, started the first journal for children and wrote several novels and popular how-to books such as The Frugal Housewife, The Mother’s Book and The Little Girl’s Own Book. Her history, The First Settlers of New England, blamed Calvinist-based racism for the treatment of Native Americans. She married David Childs, editor and publisher of the Massachusetts Journal, in 1828 when she was 26.

An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans recruited many to the anti-slavery movement, but made Child a pariah in Boston society. Her two-volume The History of the Condition of Women, in Various Ages and Nations was published in 1835. She continued abolition work, supporting herself through popular writings and newspaper columns. The Progress of Religious Ideas (1855) rejected theology, dogma, doctrines, and talked of “Providence” as the inward voice of conscience. Her funeral was presided over by Wendell Phillips, who said she was “ready to die for a principle and starve for an idea.” John Greenleaf Whittier recited a poem in her honor and The Truth Seeker memorialized her. D. 1880.

“It is impossible to exaggerate the evil work theology has done in the world.”

— Child, "The Progress of Religious Ideas Through Successive Ages" (1855)

Natalie Angier

On this date in 1958, Natalie Angier, Pulitzer Prize-winning science columnist for The New York Times, was born in New York City to a Jewish mother and a father with a Christian Science background. She attended the University of Michigan for two years, then transferred to Barnard College, where she studied English, physics and astronomy and graduated with high honors.

At 22 she became a founding staff reporter for the science magazine Discover. Throughout the 1980s, Angier worked as a senior science writer for Time magazine, as an editor for the women’s business magazine Savvy and as a professor of journalism in a graduate program at New York University. She began writing for The New York Times in 1990 and won a Pulitzer after just ten months on the job for a series of science articles. She became a columnist in 2007 for the Times’ science section.

Her books include Natural Obsessions (1988), about the world of cancer research, The Beauty of the Beastly (1995) and Woman: An Intimate Geography (1999), a National Book Award finalist and best-seller. Woman won a Maggie Award from Planned Parenthood, was nominated for the Samuel Johnson Award (Britain’s largest nonfiction literary prize) and was named one of the best books of the year by the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, People magazine, National Public Radio, amazon.com, Publisher’s Weekly, Library Journal and the New York Public Library.

In 2002 she edited The Best American Science and Nature Writing and in 2010 edited The Canon: A Whirligig Tour of the Beautiful Basics of Science. Her writing has appeared in numerous magazines, publications and anthologies. She began serving a five-year term as the Andrew D. White Professor-at-Large at Cornell University in 2007, previously filled by Oliver Sacks, Toni Morrison, Jane Goodall and others who were “distinguished contributors to cultural achievement.”

Angier, a self-proclaimed “lonely atheist,” was a guest on Freethought Radio in 2006. In The New York Times Sunday Magazine (Jan. 14, 2001), Angiers outed herself as an atheist in the article “Confessions of a Lonely Atheist”: “I’m an Atheist. I don’t believe in God, Gods, Godlets or any sort of higher power beyond the universe itself, which seems quite high and powerful enough to me. I don’t believe in life after death, channeled chat rooms with the dead, reincarnation, telekinesis or any miracles but the miracle of life and consciousness, which again strike me as miracles in nearly obscene abundance.”

Angier received an Emperor Has No Clothes Award at the 2003 FFRF national convention. In 1991 she married Rick Weiss, a former science reporter for the Washington Post. They have a daughter, Katherine Weiss Angier, who graduated summa cum laude in 2018 from Princeton with a degree in biology.

“Sure, I’m a soapbox atheist. But [my daughter] doesn’t have to take my word for anything. All she has to do is look around her, every day, to find the bible she needs — in the sky, sun, moon, Mars, leaves, lady bugs, stink bugs, possums, tadpoles, cardinals, the wonderful predatory praying mantises that have gotten really big and fat this year on all the insects this rainy year has brought. Life needs no introduction, explanation or excuse. Life is bigger than myth — except in California.”

— Angier, Emperor Has No Clothes Award acceptance speech at the 2003 national FFRF convention

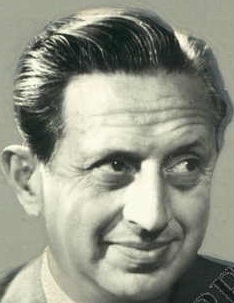

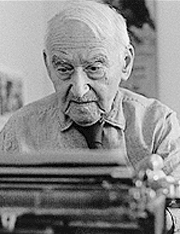

James A. Haught

On this date in 1932, journalist and author James Albert Haught was born in the rural West Virginia town of Reader, which had no electricity or paved streets. His family had gas lights and running water, while most households lived with kerosene lamps and outdoor privies. His parents never attended church, and he ignored religion.

After graduating with a high school class of 13, he worked as an apprentice printer at the Charleston Daily Mail and later was hired in 1953 as a reporter by a rival paper, the Gazette. Republican Gov. Arch Moore Jr. derisively called the Gazette “The Morning Sick Call” in the mid-1970s for its critical reporting on his administration. Moore pleaded guilty in 1990 to five felonies and served 32 months in federal prison for extortion and obstruction of justice.

Haught’s city editor in the 1950s asked him to start going to church on Sunday so he could write a weekly religion column. Despite Haught’s protest that he’d been churchless his entire life, the editor said, “Fine. That will make you objective.” Years on the church beat gradually filled him with distaste for supernatural miracle claims and he felt dishonest mingling with worshipers while not revealing his doubts about gods, devils, heavens, hells, prophecies and other dogma.

His investigative reporting led to several criminal indictments and he won about two dozen newswriting awards. He was named associate editor in 1983 and editor in 1992. When the Gazette and Daily Mail merged in 2015, he assumed the title of editor emeritus while still working full-time on editorials, personal columns and news stories. The only break from daily journalism was as a press aide to U.S. Sen. Robert Byrd for several months in 1959.

In the 1980s he started writing freethought books (12 as of this writing in 2023) and magazine essays. He served as a senior editor of Free Inquiry magazine and writer-in-residence for the United Coalition of Reason and started blogging at Daylight Atheism and Canadian Atheist. Many of his columns ran in Freethought Today and he was an FFRF Life Member.

Haught, who had four children and 12 grandchildren, shied from labels describing the degree of his religious doubt and preferred to be considered as simply an honest person who didn’t claim to know supernatural things that nobody can know. Nancy, his first wife, died in 2008 and he married retired teacher Nancy Lince in 2013. She died in 2021.

He was a longtime member of a Unitarian Universalist congregation. He once debated UU President William Sinkford after Haught observed the national organization turning “more ‘churchy’ and using god-talk. … I proposed that the denomination adopt a statement saying: ‘The UUA takes no position on the existence, or nonexistence, of God. Members are free to reach their own conclusions about this profound question.’ Actually, that statement expresses the UU reality, but leaders were afraid to put it into writing.” (United Coalition of Reason interview, Aug. 23, 2017)

Even at age 90, Haught shrugged off the frailties of age and kept on writing, including a weekly blog for FFRF’s Freethought Now. A column he wrote for his 90th birthday was titled “My Thoughts on Mortality.” He died of cancer at age 91 in hospital hospice in Charleston. (D. 2023)

PHOTO: Haught in the newsroom early in his journalism career of 60-plus years.

“Although billions of people pray to invisible gods, they’re just imaginary, as far as a sincere inquirer can tell. So, to me, the only honest viewpoint is the humanist one, which doubts the supernatural and focuses on improving human life.”

— Haught, "To Question Is the Answer" (July 2007)

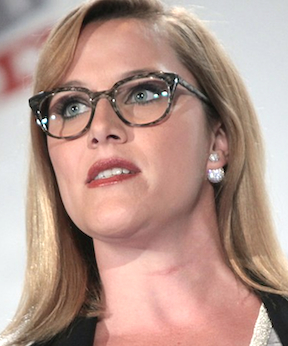

S.E. Cupp

On this date in 1979, columnist and commentator Sara Elizabeth “S.E.” Cupp was born in Oceanside, Calif. Her Catholic family moved around a lot for her father’s work with Boise Cascade lumber products.

They moved to Andover, Mass., when she was 6. She graduated from high school there and was a student during that time with the Boston Ballet. “I knew at a very young age that I didn’t really buy the whole God gamut. I didn’t know why. I wouldn’t say it was rebellion. It was skepticism. It just didn’t add up to me.” (Daily Beast, June 13, 2010)

Cupp graduated in 2000 with a B.A. in art history from Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. She earned an M.A. with a concentration in religious studies in 2010 from the Gallatin School of Individualized Study at New York University. “I was just fascinated by the pomp and ceremony and ritual nature of religion, and yet couldn’t completely get there ever; couldn’t completely wrap my mind around the idea of God.” (CNN Belief Blog, Sept. 9, 2013)

She started using S.E. Cupp in order to have a gender-free byline. At the top of her website after her name, it says “Conservative. Columnist. Commentator.” Then it says “Cupp delivers her passionate voice and fresh perspective on everything from politics, media, sports to popular culture” via her media appearances.

Her columns appeared in numerous publications, most often conservative ones, which was also where her commentary was delivered, although she was paired with a liberal on some programs to offer contrasting views. Co-hosting with Krystal Ball on MSNBC’s “The Cycle” about the role of religion in presidential elections, Cupp said GOP candidate Mitt Romney would have “no chance” running as an atheist. “And you know what? I would never vote for an atheist president. Ever,” Cupp added.

Asked why, Cupp explained: “Because I do not think that someone who represents 5 to 10 percent of the population should be representing and thinking that everyone else in the world is crazy but me.” (“The Cycle,” July 5, 2012)

Two years later on CNN, she argued that atheists on “the left” have a “militant hostility” in reaction “against intellectual diversity” and that they perpetuate the idea “that atheists are somehow disenfranchised or left out of the political process. I just don’t find that to be the case.” (“Crossfire Reloaded,” July 30, 2014)

That didn’t sit too well with Harvard University humanist chaplain Chris Stedman: “Survey data contradict Cupp. For instance, a 2014 Pew Research study found that Americans are less likely to vote for an atheist presidential candidate than any other survey category — even if they share that candidate’s political views. Faring better than atheists: candidates who have engaged in extramarital affairs and those with zero political experience.” (CNN, Aug. 22, 2014)

Cupp identifies as a Log Cabin Republican who supports equal rights for gays. Although she said in 2013 that she had never voted for a Democrat, she announced in August 2020 that she would be voting for Joe Biden for president. In May 2022, she wrote to support upholding Roe v. Wade, stating that she is pro-life but believes abortion should be legal.

Conservatism’s rightward shift with the rise of Donald Trump has perhaps moved Cupp to the left: “The insurrection at the Capitol on Jan. 6 was in many ways a Christian nationalist event. Crosses, Christian banners and signs reading ‘Jesus is my savior, Trump is my president,’ were unavoidable. … “All of this — the rise in Christian nationalism and the literal and metaphorical weaponizing of faith to intimidate opponents — while the country grows less and less religious.” (Column, N.Y. Daily News, June 22, 2022)

In that same column, she wrote: “Surely, there are atheists in Congress and running for Congress, just as there are atheists everywhere else in America, even if they remain closeted. With the right using God to coax the party into regressive, punitive and at times increasingly scary places, here’s hoping they’ll finally have the courage to come out of the shadows.”

Cupp married John Goodwin, former chief of staff to Idaho Republican U.S. Rep. Raúl Labrador, in 2013. He is head of communications for The Weather Channel. They have a son, John Davies Goodwin III, born in 2014.

PHOTO: Cupp at the 2016 Politicon in Pasadena, Calif.; Gage Skidmore photo under CC 2.0.

“I never thought about it, but as an atheist, maybe Nascar is my church?”

— Cupp, commenting that her three Sunday essentials are Nascar, Buffalo wings and Bravo. (N.Y. Times, April 29, 2011)

Joan Konner

On this date in 1931, journalist Joan Barbara Konner was born in Paterson, N.J., the daughter of Martin Weiner, who was in the textile business, and the former Tillie Frankel, an artist. She received her B.A. from Sarah Lawrence College in 1951. She earned a master’s in jounalism from Columbia in 1961 when she was 30 after raising two daughters, Rosemary and Catherine. Her marriage ended in divorce, and Catherine died in 2003.

She was hired as a journalist for the Bergen Record, where she worked on the women’s page. She left in less than two years to work at WNBC-TV, where she was a writer and producer of many documentaries. She became executive producer of “Bill Moyers Journal” during the 1980s and later was president and executive producer of Moyers’ production company, Public Affairs Television. She helped produce the acclaimed six-part docuseries “Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth” for Moyers. She worked with Alvin Perlmutter on the series and married him in 1994.

Konner ended her career in public television as executive producer for national news and public affairs for WNET/Thirteen in New York. She returned to Columbia in 1988 to become the first female dean of the Columbia School of Journalism. She was also publisher of the Columbia Journalism Review until 2000.

She wrote books on religion from the freethought point of view, such as The Atheist Bible: An Illustrious Collection of Irreverent Thoughts (2007), and You Don’t Have to Be a Buddhist to Know Nothing: An Illustrious Collection of Thoughts on Naught (2009) and is known for producing over 50 documentaries and television series that focus on ideas and beliefs. “I myself was born Jewish and I have great respect for that, but if you ask me to name what I’ve learned the most from — and what seems to guide my own behavior now — I say I’m a ‘Trans-Zen-Jewish-Quak-alist.’ ” (Read the Spirit interview, March 16, 2010.)

Konner won numerous awards and honors throughout her lengthy career, including 16 Emmys, a Peabody Award, the New Jersey Presswomen’s Lifetime Achievement Award and the New York Newswomen’s Award for Best Documentary. She died of leukemia at age 87 in Manhattan in 2018.

“I see myself as a journalist if anything. I don't call myself an agnostic but I do recognize that I will never know.”

— Konner interview in the online magazine Read The Spirit (March 16, 2010)

Charles Watts

On this date in 1836, Charles Watts was born in Bristol, England, into a family of Methodists. At age 16 he moved to London to work with his older brother in a printing office. The brothers were acquainted with many freethinkers and founded a publishing business, Watts & Co., in 1864. Along with Charles Bradlaugh and others, Watts co-founded the National Secular Society in 1866.

Watts wrote extensively on freethought, including Freethought: Its Rise, Progress and Triumph (1885). In an 1868 pamphlet on Christianity, he wrote: “In Spain religion is cruel oppression, in Scotland it is a gloomy nightmare, in Rome it is priestly dominion, while in England it is simply emotional pastime. All these different phases of Christianity indicate that theological opinions depend on surrounding circumstances, and cannot therefore be the cause of the civilisation of the world.”

He emigrated to Toronto in 1883, where he lectured and became the leader of the secularist movement in Canada. Returning to England in 1891, he worked for The Freethinker, the world’s oldest surviving freethought publication (internet-only since 2014). Watts’ wife, Kate Eunice Watts, also wrote and traveled with him. Some of her writings included The Education and Position of Woman and Christianity: Defective and Unnecessary.

Watts died at age 70 and was cremated, with his remains buried in Highgate Cemetery in North London. His son, Charles Albert Watts, developed the Rationalist Press Association, still in existence as the Rationalist Association. (D. 1906)

"The object of Christ was to teach his followers how to die, rather than to instruct them how to live.”

— from Watts' pamphlet "Christianity: Its Nature and Influence on Civilisation" (1868)

Nuala O’Faolain

On this date in 1940, Irish journalist, memoirist and feminist Nuala O’Faolain (pronounced oh-FWAY-lawn) was born in Dublin, the second of nine children. Her unhappy childhood, lacking in love, inspired much of her later writing. Her father wrote a newspaper column for the Dublin Evening Press and, according to O’Faolain, spent many nights out in Dublin with little regard for his family. Her mother “sank into despair and alcoholism” as a result. (The New York Times, May 11, 2008.)

O’Faolain attended a Catholic convent school but was expelled for unruly behavior. She studied English at University College in Dublin and medieval English literature at the University of Hull in England. She earned a B.Phil. in English from Oxford in the 1960s. After her studies, she lectured in the English department at University College and then moved to London, where she established a broadcasting producer career with the BBC.

In 1977 she returned to Ireland to produce television programs, often with feminist content about Irish women. In 1986 she started writing a weekly column for the Irish Times. Her first memoir, Are You Somebody? (1996), won her international recognition. Following were successful novels, My Dream of You (2001) and The Story of Chicago May (2006). In 2003, Almost There, a sequel to her first memoir, was published.

O’Faolain had a 15-year relationship with the feminist journalist and playwright Nell McCafferty. She died in 2008 in Dublin from lung cancer at age 68. In an interview after her terminal diagnosis, O’Faolain stated she did not believe in an afterlife. (The Independent, interview with Marian Finucane, April 13, 2008). Her May 11 obituary in The Guardian stated, “The long and illustrious list of women who challenged the status quo — and changed Irish society in the process — had no more eloquent an exponent than Nuala O’Faolain.”

Nuala O'Faolain: And though I respect and adore the art that arises from the love of God and though nearly everybody I love and respect themselves believes in God, it is meaningless to me, really meaningless.

Marian Finucane: The reason I asked you is because it is a source of comfort for many people.

O'Faolain: Well, I wish them every comfort, but it is not even bothering me. I don’t even think about it. I have never believed in the Christian version of the individual creator.— O'Faolain interview, The Independent (April 13, 2008)

Matt Taibbi

On this date in 1970, muckracking atheist journalist Matthew C. “Matt” Taibbi was born in New Brunswick, N.J. The son of an NBC reporter, he grew up in Boston and graduated from Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y. He moved to Russia in 1992 and studied and worked there and in Uzbekistan and Mongolia for over six years. In 1997 he co-edited with Mark Ames an English language newspaper called the eXile, geared to expatriates in Moscow. It provided background for his first book, with Ames and Edward Limonov, The Exile: Sex, Drugs, and Libel in the New Russia (2000).

He then started The Beast, a satirical biweekly in Buffalo, N.Y., but left to concentrate on freelancing for The Nation, Playboy, Rolling Stone and New York Press (which he left in 2005 after his editor Jeff Koyen was fired over issues raised by Taibbi’s column “The 52 Funniest Things About the Upcoming Death of the Pope”). Taibbi defended the piece as “off-the-cuff burlesque of truly tasteless jokes” to relieve readers of his “fulminating political essays.” He covered the 2008 presidential campaign for “Real Time with Bill Maher.”

He received a 2008 National Magazine Award in the category “Columns and Commentary” for his Rolling Stone columns. His article “The Great American Bubble Machine,” which detailed Goldman Sachs’ involvement in the financial meltdown, received a 2009 Sidney Award from the Sidney Hillman Foundation. His 2008 book The Great Derangement: A Terrifying True Story of War, Politics, and Religion told the story of how he infiltrated Texas evangelical pastor John Hagee’s Cornerstone megachurch and school and Hagee’s “near-absolute conquest of a very trendy niche in the market: Christian Zionism.”

He has also written Griftopia: Bubble Machines, Vampire Squids, and the Long Con That Is Breaking America (2010), The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap (2014), Insane Clown President: Dispatches from the 2016 Circus (2017) and Hate Inc.: Why Today’s Media Makes Us Despise One Another (2019). He and his wife Jeanne, a family physician, were married in 2010 and live in New Jersey with their son.

MEHTA: What role should religion play in the political arena?

TAIBBI: Well, I'm an atheist/agnostic, so I would say none. People should stick to solving the problems they have the tools to solve. If you have a budget crisis, well, human beings can do the math, work out a new tax/spending strategy, and fix that. But we don't have any tools for [divining] the will of God as it relates to, say, a new problem like high school shootings, the Iraq war, or the AIDS virus. All we have are the opinions of religious leaders whose motives may or may not be pure, and whose grasp of logic may or may not be of the highest quality. If you inject religion into the equation, the debate is necessarily going to be subjective, emotional, and inconclusive. It's also very easy for unscrupulous people to use religion to further various ends for other reasons. Hagee's humping of Israel is a great example. How do you get fundamentalist Christians to support the financial subsidy of military aid to a Jewish state? Easy; you convince them the world is going to end soon, and that we're going to be on the wrong side of Armageddon unless we support Israel.”— Interview with "Friendly Atheist" Hemant Mehta (April 29, 2008)

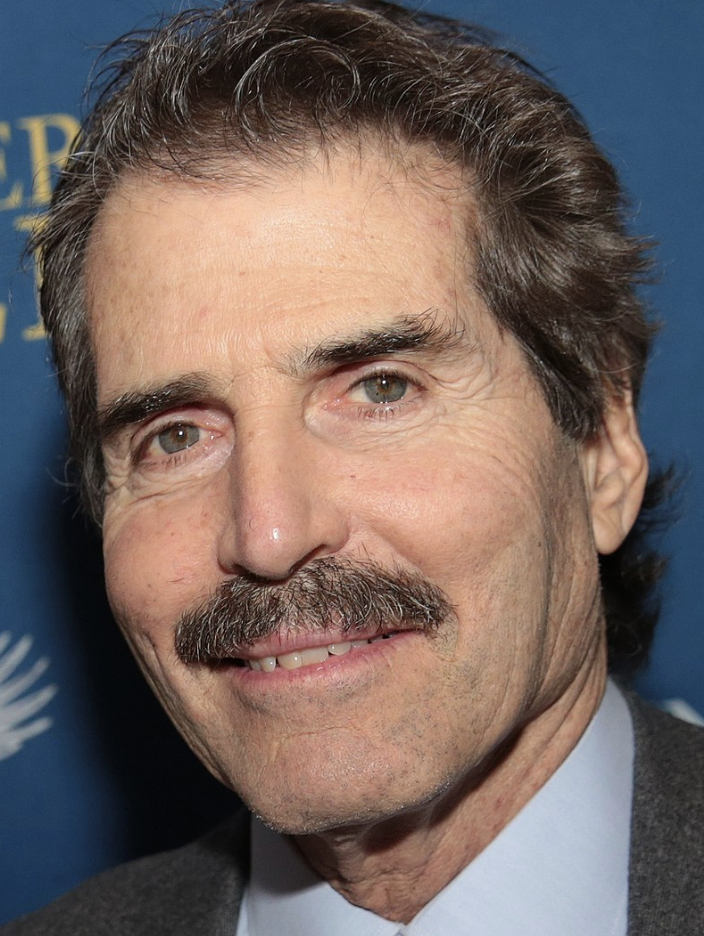

John Stossel

On this date in 1947, journalist John Frank Stossel was born in Chicago Heights, Illinois, to Jewish parents from Germany. He was raised Protestant. He attended Princeton University, earning a degree in psychology in 1969.

He worked as a reporter for several media outlets around the country, then became an editor for “Good Morning America” and in 1981 a correspondent for “20/20.” Stossel moved in 2009 to the Fox Business Channel to host “Stossel,” a weekly program that approaches issues from a libertarian perspective.

He has written three books. Give Me a Break: How I Exposed Hucksters, Cheats, and Scam Artists and Became the Scourge of Liberal Media (2005) was on The New York Times best-seller list for 11 weeks. His second book was Myths, Lies and Downright Stupidity: Get Out the Shovel: Why Everything You Know is Wrong (2007), and the third was No, They Can’t: Why Government Fails — But Individuals Succeed (2012).

Stossel has received 19 Emmy Awards and five awards from the National Press Club. Stossel is married to Ellen Abrams and has two children, who were raised Jewish by his wife. In a “Stossel” episode (Dec. 16, 2010), he identified himself as agnostic. “God may exist, but I want more evidence and I’ve looked for it,” he said, adding that he can’t bring himself to see the bible as “the word of God.”

PHOTO: Stossel in 2018 in Teaneck, N.J.; Gage Skidmore photo. CC 3.0

“I want to [believe]. I see the peace and purpose it gives most of you who believe, and I tried. I just can’t.”

— Stossel to Gretchen Carlson on Fox News (Dec. 13, 2012)

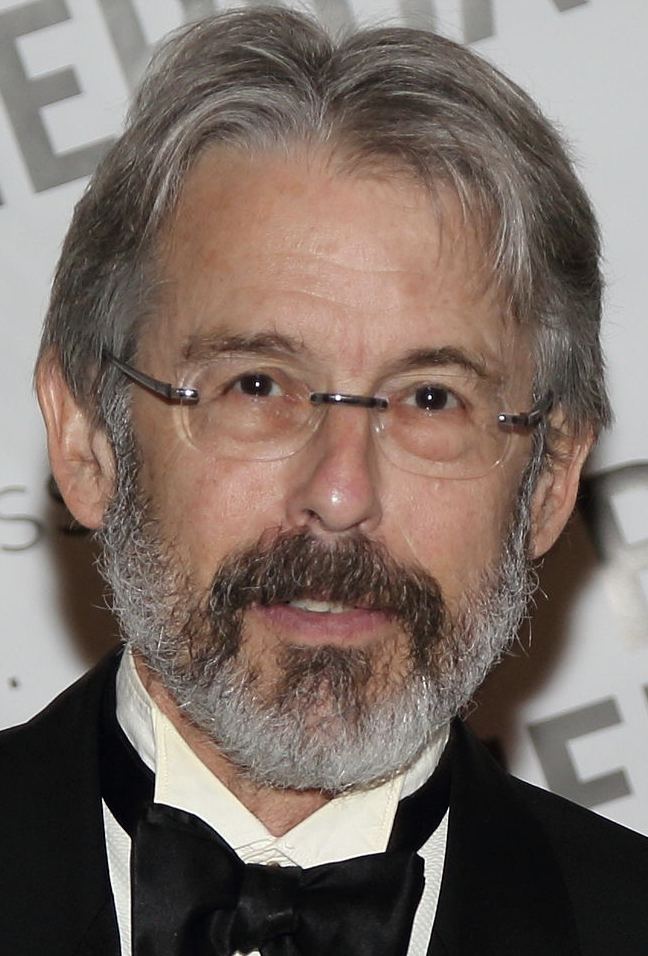

Michael Kinsley

On this date in 1951, journalist Michael Kinsley was born in Detroit. He earned his B.A. at Harvard in 1972, attended Oxford and earned his law degree from Harvard Law School in 1977. Named editorial and opinion editor of the Los Angeles Times in June 2004, Kinsley previously was founding editor of Slate.com. His journalistic credentials include writing for Time magazine, the Washington Post and Vanity Fair.

In 1979 he became editor of The New Republic (rejoining the magazine in 2013 after a long hiatus). He has been editor-in-chief of Harper’s and editor of the American Survey Department of The Economist. Kinsley was managing editor of the Washington Monthly and co-hosted CNN’s “Crossfire” for six years. He played himself in the 1993 movie “Dave.”

In a December 2004 Los Angeles Times column about gay marriage, he wrote, “Such a development is not just amazing. It is inspiring. American society hasn’t used up its capacity to recognize that it harbors injustice, and it remains supple enough to change as a result. In fact, the process is speeding up. It took African American civil rights a century, and feminism half a century, to travel the distance gay rights have moved in a decade and a half.”

His books include Please Don’t Remain Calm: Provocations and Commentaries (2008) and Old Age: A Beginners Guide (2016). Kinsley identifies as a “nonbeliever.” In 2002 he married Patty Stonesifer, a top executive at Microsoft and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. That same year he revealed he had Parkinson’s disease and in 2006 underwent deep brain stimulation, surgery designed to reduce its symptoms.

According to a humorous postscript to his Time column anticipating the surgery, the operation went well: His first words out of the operating room were, “Well, of course, when you cut taxes, government revenues go up. Why couldn’t I see that before?”

PHOTO: Kinsley during an interview with Brian Lamb on C-SPAN (April 12, 2016).

“As a devout believer, [Marine Corps Gen. Jerry] Boykin may also wonder why it is impermissible to say that the God you believe in is superior to the God you don’t believe in. I wonder this same thing as a nonbeliever: Doesn’t one religion’s gospel logically preclude the others’? (Except, of course, where they overlap with universal precepts, such as not murdering people, that even we nonbelievers can wrap our heads around.)"

— Kinsley, "The Religious Superiority Complex: It's OK to think your God's the greatest, but you don't have to rub it in," Time magazine (Nov. 3, 2003)

Jorge Ramos

On this date in 1958, journalist and author Jorge Gilberto Ramos Ávalos was born in México City to Catholic parents. His father, with whom he became estranged because of his career choice, was an architect. After graduating from the Universidad Iberoamericana in communications, he worked as a TV reporter. When he was censored for criticizing the government, he came to the U.S. on a student visa and graduated from UCLA Extension in 1984. He later earned a master’s at the University of Miami and became a U.S. citizen in 2008.

Ramos, news anchor for Noticiero Univision since 1986, also hosts Univision’s weekly public affairs program “Al Punto” and Fusion’s “America with Jorge Ramos.” He’s written 10 books, has a syndicated column and actively promotes literacy in the Latino community. Ramos has received eight Emmys and numerous journalism awards and is consistently named as one of the most influential Latinos.

In an April 2014 Fusion column, he criticized Pope Francis for presiding over the canonization of Pope John Paul II, calling it “an insult to the countless people who have been sexually abused by Catholic priests. During his papacy, from 1978-2005, this newly anointed ‘saint’ remained silent as these predators targeted children in parishes around the world.” In an interview with CNN México posted on YouTube in 2013, Ramos was asked, “Pero lo crees en Dios?” (“Do you believe in God?”), he answered “no.”

At an August 2015 Donald Trump press conference in Iowa, Ramos tried to question Trump about immigration without being called on and was told several times to sit down and “Go back to Univision” before being escorted out by security. Ramos is based in Miami, is twice divorced and has a daughter, Paola, born in 1988, and a son, Nicolas, born in 1998.

Public domain photo by Bill Ingalls, NASA

TERRY GROSS: “So when you left Mexico and were faced with a different part of the Catholic Church, did you consider going back or were you just done?”

RAMOS: “No, I was done. I was done. … [O]nce I started going to college, and once I realized that nobody really knows if there’s afterlife, that there’s really no explanation, no religious explanation on why children die, why children have cancer, why all the cruelty in wars happen, why all these terrible things that I’ve seen as a journalist. Once you realize that there’s no religious explanation, then I really had no choice but to leave Catholic Church and I became an agnostic.”— Interview, NPR "Fresh Air" (Oct. 5, 2015)

Cenk Uygur

On this date in 1970, Cenk Kadir Uygur was born in Istanbul, Turkey. When he was 8, his family moved to New Jersey, where he graduated from high school. He majored in management at the Wharton School of Business, and later earned a J.D. from Columbia University. Uygur was raised as a “not-very-strict” Muslim but lost his faith after taking a college course about Islam and reading the Quran and the Bible.

He now describes himself as a secular humanist and an agnostic. He worked as an attorney, then became involved in local talk radio and television news production. In 2004 he created the online news talk show “The Young Turks.” In addition to internet video, the show was also broadcast on Sirius Satellite Radio until 2010.

Uygur has appeared on many television networks as a commentator, including MSNBC, Fox News and Al Jazeera. In 2010 he became a substitute host and paid contributor for MSNBC. In January 2011 he became the anchor of MSNBC Live, but left the network in June 2011 and started hosting “The Young Turks with Cenk Uygur” on Current TV, which went off the air in 2013.

In 2018 “The Young Turks” launched its own 24-hour channel on YouTube TV. In 2010 he accepted FFRF’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award. He received the American Humanist Association’s 2012 Humanist Media Award. Uygur and his wife Wendy Lang have a son, Prometheus Maximus, and a daughter, Joy.

Uygur apologized in 2017 for a series of blog posts from 1999 to the mid-2000s that were sexist toward girls and women, calling what he wrote “offensive, insensitive and ignorant.” He said he wrote the posts, deleted more than a decade earlier, while he was a conservative and before he underwent a political transformation into a liberal.

"I'm offended by [evangelical leaders'] actions, but I'm not offended by their opinion. They believe in a sky god who's going to suck them up into the sky with a vacuum cleaner. What's there to get offended by? That's funny! That's hilarious! Have at it, Hoss, I'd love to see it!"

— Uygur speech to FFRF's 2010 national convention

Vladimir Pozner Jr.

On this date in 1934, Vladimir Vladimirovich Pozner was born in Paris to a Russian-Jewish father, also named Vladimir, and a French Catholic mother, Géraldine Lutten. The couple separated when he was 3 months old, and he and his mother moved near her family in New York City. His parents later reunited and moved back to Paris in 1939.

Fleeing World War II, they returned to New York in 1940. Pozner briefly attended Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan until his father, under FBI scrutiny for pro-Soviet activities and suspected spying, moved them to East Berlin and then to Moscow. He majored in human physiology at Moscow State University and earned a B.S. in 1958.

In 1961 he joined Novosty Press Agency (later learning his department was actually a KGB “disinformation” effort) and then became editor of Soviet Life and Sputnik magazines. He was a commentator on Radio Moscow from 1970-86. Pozner was permitted to travel abroad from 1977 to 1980, when his passport was revoked for criticizing Russia’s military incursions in Afghanistan.

In the late 1980s he began appearing regularly on ABC’s “Nightline,” the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the BBC and other TV networks in the U.S. and abroad, all by satellite hookup because he was not allowed to travel. In 1985-86 he co-hosted two shows, also by satellite, with Phil Donahue, which brought glasnost to Soviet TV. In 1989, he resigned from the Communist Party.

He moved to New York City in 1991 to work with Donahue. Parting with Illusions (1990) became a national best-seller, which was followed by Eyewitness (1991). In 1997, Pozner returned to Moscow to host two TV shows. He served as president of the Academy of Russian Television and dean of the Pozner School of Television Journalism. He has won two Emmy certificates and several other journalism awards.

He married Valentina Chemberdzhi (1957–67), Yekaterina Orlova (1969–2005) and Nadezhda Solovieva (2005). He has often identified himself publicly as an atheist and has advocated for the right to euthanasia and legalization of same-sex unions and recreational drugs in order to cut down on trafficking.

“As it is known, I am an atheist. I stridently believe there is no God. It’s not that I run around shouting, ‘There isn’t, there isn’t’ from morning to evening, but I do not hide my convictions.”

— Pozner interview with Radio Free Europe (May 16, 2017)

Robert Scheer

On this date in 1936, journalist Robert Scheer was born in Bronx, N.Y. He attended public schools and graduated from City College of New York. He further studied economics as a fellow at Syracuse University, Yale and the University of California-Berkeley’s Center for Chinese Studies.

From 1964 to 1969, Scheer was the Vietnam correspondent, managing editor and editor-in-chief of Ramparts magazine. He then worked as a journalist and columnist at the Los Angeles Times for nearly 30 years, serving as one of the most progressive voices on the staff. He was fired after decades of dedication to the paper for reasons he believes stemmed from ideological differences with the publisher.

Scheer has interviewed a number of presidents, including Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, George Bush, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. In 1993 at the Los Angeles Times, he launched a nationally syndicated column and worked as a contributing editor for 12 years. This column became known as Truthdig, which morphed into an online site and relocated to the San Francisco Chronicle, where Scheer is the editor-in-chief of the independent journal.

Scheer has written several books, including The Five Biggest Lies Bush Told Us About Iraq (2004), co-authored with his son Christopher Scheer and Lakshmi Chaudry, The Pornography of Power: How Defense Hawks Hijacked 9/11 and Weakened America (2008) and They Know Everything About You: How Data-Collecting Corporations and Snooping Government Agencies Are Destroying Democracy (2015). He has won numerous awards such as the James Aronson Award for Social Justice Journalism, the 2010 Distinguished Work in New Media Award, and the 2011 Izzy Award for outstanding achievement in independent media. Additionally, Truthdig is a four-time recipient of the Webby Award for best political blog.

Scheer teaches as a clinical professor of communications in the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California. He is former co-host of “Left, Right, and Center,” a political radio program on National Public Radio station KCRW. He hosts “Scheer Intelligence” at KCRW, where he interviews people who discuss the day’s most important issues, offering an often surprising perspective. He lives in California with his wife Narda Catharine Zacchino.

PHOTO via Shutterstock by Debby Wong

"I was always raised with the idea there was an inherent value to human life — and [that] certainly was not based on religion. I think it was enhanced by not being religious. I had to find meaning in the secular life. You know, I couldn't be waiting for another life. And I couldn't find it just in scripture or something. My parents had both basically rebelled against the life of scripture. They saw its downside."

— Scheer, The Real News Network interview (July 5, 2015)

Hugh Hefner

On this date in 1926, Playboy mogul Hugh Marston Hefner was born in Chicago, the firstborn of Grace and Glenn Hefner’s two sons. His parents were strict Methodists. He went to school in the city and started a school newspaper at Steinmetz High School. He served in the U.S. Army during World War II. After discharge in 1946, he studied at the Chicago Art Institute for two years and then at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, completing a degree in psychology in 1950.

After college he began working as a promotional copywriter at Esquire in Chicago, which was then the premier men’s magazine. After three years he left in frustration, determined to start his own publication. With $8,000 from 45 investors, Hefner started Playboy magazine. The first issue was published in December 1953. It was an instant success, selling 50,000 copies. By 1959 Playboy was selling almost a million copies a month and Hefner was expanding his success. Playboy Enterprises established private key clubs, staffed with the iconic “bunnies” as hostesses, high-end resorts and modeling agencies. There were books and films and two television series. By 1970 the publication was selling 7 million copies a month.

After suffering a minor stroke in 1985, Hefner largely stepped back from Playboy Enterprises, leaving his daughter, Christie Hefner, at the helm. He instead focused on philanthropic efforts, making a few notable TV and film appearances to continue promoting the Playboy brand. He championed the issues of free speech and freedom of the press. He established the Playboy Foundation in 1965 to provide grants to nonprofits fighting censorship or researching human sexuality. The foundation also sponsors the Freedom of Expression Award, which is given at Sundance Film Festival every year.

While Playboy became a byword for objectification of women, with Gloria Steinem writing a famed piece, “A Bunny’s Tale,” for Show magazine on May 1, 1963, exposing what it was like to be a “Bunny,” Hefner placated some feminist critics by defending women’s reproductive rights. The A&E network’s 12-part miniseries titled “Secrets of Playboy” started airing in early 2022. Directed by Alexandra Dean, it reexamined Hefner and Playboy Enterprises through the lens of 2022 and in the wake of #MeToo. Dozens of women appear in the documentary to allege decades of sexual predation, including rape, and extensive use of illegal drugs and secret recordings inside the Playboy Mansion in the Holmby Hills neighborhood of Los Angeles.

In response, an open letter signed by about 500 people defended Hefner, calling the allegations unfounded: “From all we know of Hef, he was a person of upstanding character, exceptional kindness, and dedication to free thought.” In a statement, the company said “today’s Playboy is not Hugh Hefner’s Playboy. We trust and validate these women and their stories and we strongly support those individuals who have come forward to share their experiences.”

Alexandra Dean: “His progressive reputation was like a shield that stopped a lot of these allegations from touching him. It was just too hard to believe that this guy who was always promoting women at his company and was a progressive champion, how could he secretly be attacking women behind closed doors?” (Variety, Feb. 7, 2022) “That other side of Hugh Hefner really does need to have a reckoning now — we need to figure out how to reconcile the two Hugh Hefners and now decide what his real legacy is.”

Hefner married three times: to Mildred Williams (1949), Kimberley Conrad (1989) and Crystal Harris (2012). He also lived with a succession of younger “partners” at the mansion. He was 86 when he married Harris, a 26-year-old former Playmate. He had a son and a daughter with Williams and two sons with Conrad. He died at the mansion at age 91 of cardiac arrest and was interred in a mausoleum drawer next to Marilyn Monroe in Westwood Memorial Park. (D. 2017)

PHOTO: Hefner in 2010; Glenn Francis photo under CC 3.0.

“It's perfectly clear to me that religion is a myth. It's something we have invented to explain the inexplicable."

— Hefner interview in Playboy (January 2000)

Leo Rosten

On this date in 1908, journalist and political scientist Leo Rosten was born in Łódź, now a part of Poland. He was born into a Yiddish-speaking family and emigrated to the U.S. at age 3, where his trade unionist parents opened a knitting shop in the Chicago area. He grew up in a working-class neighborhood in which the primarily Jewish residents spoke Yiddish and English. From an early age, Rosten had an interest in books and language that led him to write his first story at the age of 9. He put himself through college and received degrees from the University of Chicago and the London School of Economics.

Emerging into the workforce during the Great Depression, Rosten was unable to find a job that fit his degree. Instead he began teaching English to immigrants at night school. This experience led to his most popular work, The Education of H*Y*M*A*N*K*A*P*L*A*N (1937), published under the pseudonym Leonard Q. Ross. In 1949 he joined the staff at Look magazine in New York, where he remained until 1971.

Rosten also lectured at Columbia University, Yale and the New School of Social Research in New York City. He wrote scripts for films such as “The Conspirators” (1944), “The Dark Corner” (1946) and “Double Dynamite” (1951). Rosten is recognized for his humorous encyclopedic collections The Joys of Yiddish (1968) and The Joys of Yinglish (1989). He also edited A Guide to the Religions of America (1955), Religions in America (1963) and A Guide to the Religions of America: Ferment and Faith in an Age of Crisis (1975).

He married Priscilla Ann Mead, a sister of anthropologist Margaret Mead, in 1935. They had two daughters and a son before divorcing in 1959. She took her own life at age 48 later that year. Rosten married Gertrude Zimmerman in 1960. He died at age 88 in New York City. (D. 1997)

"The purpose of life is not to be happy — but to matter, to be productive, to be useful, to have it make some difference that you lived at all."

— Rosten, "The Myths by Which We Live," The Rotarian, Evanston, Ill. (September 1965)

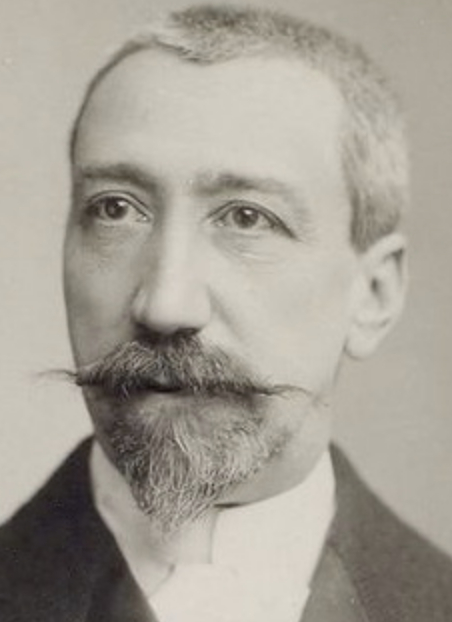

Anatole France

On this date in 1844, Anatole France (né François-Anatole Thibault) was born in Paris. A lifelong atheist, France was known for his anti-clericalism. France was a journalist, poet and writer whose breakthrough novel, The Crime of Sylvestre Bonnard (1881) centered around a skeptical scholar, perhaps modeled after the author himself. It was awarded a prize from the French Academy. France’s style, dry and ironic, was modeled in part on Voltaire and influenced by the French Enlightenment.

In 1905 he wrote a critical treatise, The Church and the Republic, which was instrumental in the campaign to disestablish the Catholic Church as the state religion. He served as an honorary president of the French National Association of Freethinkers. Penguin Island (1908) is France’s irreverent tale about a nearsighted abbot who baptizes penguins by mistake. In The Revolt of Angels (1914), France revisits Milton’s “Paradise Lost.” France depicted an angel leading a revolt after being influenced by the writings of Lucretius. With other writers, France came to the defense of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish captain falsely indicted for treason, and was a voice for reform.

His collection of aphorisms is called The Garden of Epicurus. France was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1921 “in recognition of his brilliant literary achievements, characterized as they are by a nobility of style, a profound human sympathy, grace, and a true Gallic temperament.” D. 1924.

"The thoughts of the gods are not more unchangeable than those of the men who interpret them. They advance — but they always lag behind the thoughts of men. … The Christian God was once a Jew. Now he is an anti-Semite."

— France letter to the Freethought Congress in Paris (1905), cited by Joseph McCabe in "Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists"

Peter Watson

On this date in 1943, Peter Frank Patrick Watson was born in Birmingham, England. An intellectual historian and investigative journalist, he was educated at the universities of Durham, London and Rome, later living in the U.S. He has written for The Observer, The New York Times, Punch and The Spectator and is the author of fiction, as well as many books on art history, biography, psychology and true crime. Between 1997 and 2007, he was a research associate at the Illicit Antiquities Research Centre at Cambridge University.

His books include The Age of Nothing: How We Have Sought to Live Since the Death of God (2014, published in the U.S. as The Age of Atheists: How We Have Sought to Live Since the Death of God), The Medici Conspiracy: The Illicit Journey of Looted Antiquities from Italy’s Tomb Raiders to the World’s Greatest Museums (2006, with Cecilia Todeschini), Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud (2005), Modern Mind: An Intellectual History of the 20th Century (2001) (also published as A Terrible Beauty), Sotheby’s: The Inside Story (1998), Landscape of Lies (1989) and The Caravaggio Conspiracy (1984).

In Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, Watson seeks a new way to tell the history of the world from prehistory to modern day, asserting that human knowledge is divided into two realms: inward (philosophy and religion) and outward (observation and science). His stance supports the latter. Twins: An Uncanny Relationship? (1982), explores behavior patterns shared by identical twins, “to offer a rational alternative to mumbo jumbo for explaining many of the coincidences reported in twin studies, ” according to a Los Angeles Times review.

“A few saints and a little charity don’t make up for all the harm religion has done over the ages,” he said on CBC News, May 5, 2007. When asked about the good that religion has done in the world in an interview by The New York Times Magazine (Dec. 11, 2005), Watson replied: “I lead a perfectly healthy, satisfactory life without being religious. And I think more people should try it.”

PHOTO: Watson speaking at Cambridge in 2008; Juan Jaen photo under CC 2.0.

"Religion has kept civilization back for hundreds of years, and the biggest mistake in the history of civilization, is ethical monotheism, the concept of the one God. Let’s get rid of it and be rational."

— Watson interview, CBC News (May 5, 2007)

Derek Humphry

On this date in 1930, journalist, author and activist Derek Humphry was born in Bath, England, to Bettine (Duggan) and Royston Humphry. His father was a traveling salesman and his mother had been a fashion model before marrying.

Growing up in a broken home during World War II, Humphry received a substandard childhood education. He attended close to a dozen different schools before leaving the school system at the age of 15 to pursue a career in journalism. He worked for the Yorkshire Post as an editorial manager prior to being drafted for the British Army at age 18.

Not long after his service, he resumed his career in journalism and became a reporter on the Manchester Evening News, the largest evening UK newspaper. During his journalism career, Humphry specialized in issues of race relations, immigration, prison conditions, police brutality and corruption. This led to the production of Because They’re Black (1971), a book that argued for racial harmony in Britain and won him the Martin Luther King Memorial Prize.

In 1978 he accepted a position as a special feature writer for the Los Angeles Times and moved to the U.S. The next year he published Jean’s Way, based on the 1975 assisted suicide of his first wife after a long struggle with metastasized breast cancer. According to the Times of London, she drank an overdose of a barbiturate, an analgesic and a generous helping of sugar mixed with coffee. “She gulped it all down, said, ‘Goodbye, my love,’ lost consciousness and stopped breathing within 50 minutes.”

In 1976 he had married Ann Wickett, an American studying Shakespeare in England. His investigative series for the Los Angeles Angeles Times was titled “The Quality of Dying in America” and led to him touring the country and speaking to doctors, nurses, scientists, ethicists and funeral home directors.

He and Ann started the Hemlock Society, which they ran out of the garage of their home in Santa Monica, in 1980. He wrote other related books, including Final Exit: The Practicalities of Self-deliverance and Assisted Suicide for the Dying (1991), which marked the emergence of the Death with Dignity movement in the U.S., Freedom to Die: People, Politics & The Right-To-Die Movement (1998) and Good Life, Good Death: The Memoir of a Right to Die Pioneer (2017).

Tragically, Ann killed herself with an overdose in 1991 in the wake of a tempestuous marriage and public accusations back and forth with Humphry, who had married Gretchen Crocker, a former friend of Ann’s, in 1990. The Hemlock Society split into two separate organizations — Compassion and Choices and Final Exit Network.

In a 1995 interview, Humphry was asked if he was a religious person and replied that he was an atheist. He called the Catholic Church “a dedicated opponent.” He died at age 94 at a hospice in Eugene, Oregon, of congestive heart failure and was survived by Gretchen and three sons from his first marriage. (D. 2025)

"The euthanasia movement's clash with religion is the heart of the struggle. People lose sight of that. But in a small way, it's altering 2,000 years of Christianity."

— Humphry, "The Center for Bioethics and Human Dignity Presents Dignity and Dying: A Christian Appraisal" (1996)

Yoram Kaniuk

On this date in 1930, author and painter Yoram Kaniuk was born in Tel Aviv in the British Mandate of Palestine. His father was the first curator of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. His godfather, Hayyim Nahman Bialak, was a pioneer of modern Hebrew poetry and his grandfather taught Hebrew and wrote textbooks.

While Kaniuk was still a teen, he served in Israel’s 1948 War of Independence. While serving, he was wounded when an Englishman disguised in a kaffiyeh (headdress) shot him in the legs. This, along with other of Kanuik’s profound experiences, inspired the nearly 30 novels he produced. Some of Kaniuk’s best-known works are Hemo, King of Jerusalem (1948), Confessions of a Good Arab (1984) and His Daughter (1988). His writings focused on the war, the Holocaust and the prospects for peace between Israelis and Palestinians.

Kaniuk spoke out against religious extremism and in 2011 won a legal battle in the district court of Tel Aviv in which he successfully appealed to change the status of his official national identity from Jewish to no religion. He advocated for the freedom of the next generation to identify as Jewish by nationality rather than by religion.

In his final years he battled bone marrow cancer and became fascinated with death. His final novel, Between Life and Death, detailed the four months he spent in a coma near the end of his existence. Upon his death, Kaniuk donated his body to science to avoid ultra-Orthodox funeral rituals.

In 1958 while living in the U.S., Kaniuk married Miranda Baker, a Christian, and returned to Israel with her. They had two daughters, Aya and Naomi. He died of cancer at age 83. (D. 2013)

"[Israel] established a state out of religion rather than the nation we almost became. Along the way we did not stop in the hallway of civilization, and religion attached itself to us like a leech, because that is the only way it survives, and now it has come back and returned."

— Kaniuk, quoted a month before he died, "Yoram Kaniuk's last published words: 'We messed it up." (The Times of Israel, June 9, 2013)

George Will

On this date in 1941, journalist and author George Frederick Will was born in Champaign, Ill. His father was a philosophy professor, specializing in epistemology, at the University of Illinois. Will has a bachelor’s degree from Trinity College in Hartford, Conn. (1962), a master’s in politics from Oxford University (1964) and a Ph.D. in politics from Princeton University (1968).

Will taught political philosophy at Michigan State University, the University of Toronto and then at Harvard. He served on the staff of U.S. Sen. Gordon Allott (R-Colo.) from 1970-1972. He edited National Review from 1972 to 1978. He’s generally regarded as a libertarian-style conservative. In 1974 he started writing a twice-weekly column for the Washington Post and by 1976 was a contributing editor and columnist for Newsweek. He joined ABC as a news analyst in the early 1980s and has since been a contributor to Fox News, MSNBC and NBC.

Will won a Pulitzer Prize for Commentary in 1977. His Newsweek and newspaper columns have been published in five books and he has authored books on other subjects such as political philosophy and baseball. His book Men at Work: The Craft of Baseball (1989) was the top national best-seller for over two months. Will has three children from his first marriage with Madeline Marion (divorced 1991). He married Mari Maseng in 1991. They have a son together.

Will taught a freshman seminar titled “Varieties of American Conservatism” at Princeton during the 2018-19 academic year.

PHOTO: Will at a Nationals-Orioles baseball game in 2011; photo by Keith Allison under CC 2.0.

“I’m an amiable, low-voltage atheist.”

— Will interview, The Daily Caller (May 3, 2014)

Robyn Blumner

On this date in 1961, Robyn Ellen Blumner was born in New York City. She grew up in Glen Cove and graduated from Cornell University with a B.S. in industrial and labor relations in 1982 and from the New York University School of Law in 1985. She worked as a labor lawyer in New York and volunteered for the American Civil Liberties Union after graduation, becoming executive director of the Utah ACLU from 1987 to 1989 and the Florida ACLU from 1989 to 1997.

She worked as a columnist from 1998 to 2014 for the St. Petersburg Times (later the Tampa Bay Times) in Florida and served as a member of the editorial board. Her weekly column was nationally syndicated by Tribune Media Services. Blumner often wrote about issues of civil liberties, workers’ rights and the separation of church and state. Blumner openly declared her atheism in several of her columns. She was awarded the Freedom From Religion Foundation’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award in 2004 for her plain speaking on religion and the First Amendment.

In 2014 Blumner joined the Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science as executive director. After the 2016 merger of the Dawkins Foundation with the Center for Inquiry, Blumner took over from Ronald Lindsay as CEO and president of CFI. She is married and lives in Washington, D.C.

"My faith is in mankind and the marvels accomplished by human ingenuity and drive. Why that makes me a pariah to [Tampa City Council member Kevin] White and others like him is beyond my ken. It certainly says more about them than me."

— Blumner, "I'm an atheist — so what?” St. Petersburg Times (Aug. 8, 2004)

Seymour Hersh (Quote)

“Our country has been hijacked by a bunch of religious nuts. But how easy it was. That’s a little scary.”