feminists

Simone de Beauvoir

On this date in 1908, French author and atheist Simone de Beauvoir was born in Paris to Georges Bertrand de Beauvoir, a legal secretary, and Françoise de Beauvoir (née Brasseur), a wealthy banker’s daughter and devout Catholic. A deeply religious child, she initially wanted to be a nun but at age 14 had a crisis of faith and concluded there was no God. She instead studied and taught philosophy and wrote prolifically.

Educated at the Sorbonne, de Beauvoir played a major role in the French Existentialist movement, along with close companion and atheist Jean-Paul Sartre. She is best-known for her monumental work The Second Sex (1949), in which she posited that society treats woman as “the other.” She also wrote popular novels and other nonfiction such as A Very Easy Death (1964). De Beauvoir championed freedom as the ultimate good.

She and Sartre were involved romantically from 1929 until his death in 1980. She never married or had children while engaging in a number of open relationships, including with women. Perhaps her most famous lover was American author Nelson Algren, whom she met in Chicago in 1947. She died of pneumonia at age 78 and is buried next to Sartre in Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris. (D. 1986)

PHOTO: Moshe Milner photo, Creative Commons 3.0

"Man enjoys the great advantage of having a God endorse the codes he writes; and since man exercises a sovereign authority over woman, it is especially fortunate that this authority has been vested in him by the Supreme Being. For the Jews, Mohammedans, and the Christians, among others, man is master by divine right; the fear of God, therefore, will repress any impulse toward revolt in the downtrodden female."

— Simone de Beauvoir, "The Second Sex" (1949, translated and edited by H.M. Parshley, 1953)

Alice Paul

On this date in 1885, feminist Alice Stokes Paul was born in Moorestown, N.J., to a Quaker family which believed in the equality of the sexes. She attended Swarthmore College, then spent a year as a student at the New York School of Philanthropy while working at a settlement house. Paul earned a master’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania in economics and sociology, then won a fellowship to study in England. She took courses at the University of Birmingham and London School of Economics and worked in the British settlement movement.

Paul was arrested and jailed several times in England for joining in brick-throwing at government buildings and took part in hunger strikes. Returning to New Jersey in 1910, she lectured in favor of adopting the British militancy. That year she stopped speaking to Quaker groups after her views were repudiated by them and transferred her allegiance to pure feminism. Like Quaker-raised Susan B. Anthony, Paul became an agnostic, according to Warren Allen Smith in Who’s Who in Hell. Her story inspired the 2004 HBO film “Iron Jawed Angels” in which she was portrayed by Hilary Swank.

Teaming up with her New York friend Lucy Burns, Paul talked the National American Woman Suffrage Association into letting them take over its congressional committee with help from Jane Addams, in 1912. They set up shop in Washington, D.C., organizing a historic parade of suffragists on March 3, 1913, upstaging the inauguration of President Woodrow Wilson. Peacefully parading women were attacked by a violent mob, which created huge headlines and reinvigorated the suffrage campaign.

During World War I, Paul and supporters picketed the White House with placards asking “How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?” When mobs attacked, police arrested more than 100 suffragists, many of whom were sentenced to notorious workhouses. Paul and other hunger strikers were force-fed, and she was even transferred to a psychiatric hospital. The public outcry forced Wilson to unconditionally release the women. Demonstrations continued and Congress finally enacted the suffrage amendment, ratified by the states in 1920.

Paul went to law school, earning three degrees, then began promoting the Equal Rights Amendment, which she called the Lucretia Mott Amendment. Many women’s groups at the time, including the League of Women Voters and Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, opposed the ERA on the grounds that women needed protective legislation. The amendment was first introduced into Congress in 1923. Paul lobbied for it in every successive session until 1972, when it passed. The combined forces of the tax-exempt religious lobbies defeated the ratification process in 1982 after it failed to gain support in the required number of states.

Paul, who never married, died at age 92 at a Quaker facility in New Jersey, less than a mile from her birthplace. (D. 1977)

PHOTO: Paul in 1915.

"Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex."

— From the Equal Rights Amendment drafted by Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman

Cleo Fellers Kocol

On this date in 1927, Cleo Fellers Kocol was born in Cleveland, Ohio. (She’s always been glad to share a birthday with Jack London, as her beliefs, or lack thereof, often echoed his.) She grew up in a nonreligious household and followed proudly in her mother’s intrepid feminist footsteps: “I still look back on our Sundays as magical. They were family time with games led by Dad and extended family taking part, everyone free of religion.” After high school, she worked for the Department of the Navy during World War II and then as a medical secretary, doctor’s assistant and assistant hospital administrator.

At age 43 she married Hank Kocol, a health physicist. Her feminism and atheism came to the fore when she and Hank lived in New Jersey in the 1970s and joined FFRF and the American Humanist Association. She served on AHA’s national board and chaired its feminist caucus for many years and was its Humanist Heroine in 1988. The Kocols moved to Washington state in 1979 and became part of a weekly Sunday picket at the Mormon Temple in Bellevue to protest the church’s opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment. She and 20 others were arrested in 1980 for chaining themselves to the temple gates to stop Mormon President Spencer Kimball from entering, the first of her three civil disobedience arrests.

Moving to California, they became charter members of Atheists and Other Freethinkers, started a highway cleanup project and were active in the Humanists of Greater Sacramento. In the early 1980s, Kocol wrote and performed three, hour-long women’s history shows she presented throughout the U.S. She was commissioned by the Navy to write and perform a short play about “Amazing” Grace Hopper, a computer pioneer and one of the first women to achieve the rank of Navy commodore.

Her memoir “The Last Aloha” was published in 2015. It details her humanism and feminism and life with Hank, from their meeting in 1970 to their “carrying forth the freethinker’s word” around the world to his death in 2013. She died at age 90. (D. 2016)

"Not the church, not the state, women must decide our fate."

— Kocol's favorite chant while protesting for equal rights

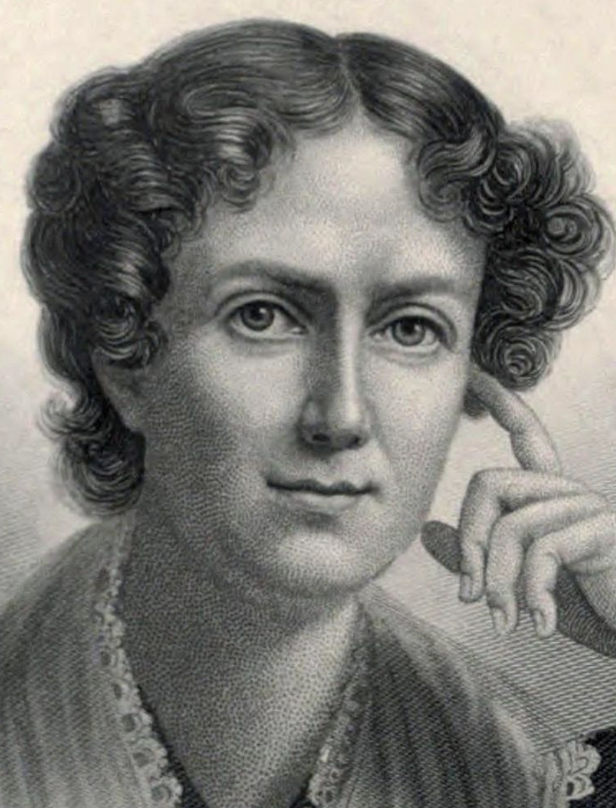

Ernestine L. Rose

On this date in 1810, Ernestine Louise Rose, née Potowski, was born in a Jewish ghetto in Poland. As the only child of an Orthodox rabbi, she was “a rebel by the age of five.” The dedicated activist became 19th-century America’s most outspoken atheist and its first lobbyist for women’s rights. Rose championed the Married Women’s Property Act first introduced by freethinking Judge Thomas Hertell in the New York Legislature in 1836, which became a model law when enacted in 1848.

After moving from Poland to England in 1830, she married William Ella Rose, a jeweler and fellow Owenite. They moved to New York in 1836 and became U.S. citizens. Rose had the distinction of being barred as an atheist from the U.S. Capitol by its chaplain in 1854. Responding to one religious heckler who turned off the gas lights during her lecture in 1853, she brought down the house by quipping that “one of the true things we find in the bible, that some there are ‘who love darkness better than light.’ ”

Known as the “Queen of the Platform,” the ringletted woman’s rights activist was frequently harassed by minister-led mobs. Her best-known freethought speech, “A Defense of Atheism,” was delivered in 1861 and is reprinted in the anthology Women Without Superstition. Rose lectured widely for women’s rights, atheism and abolition, retiring to England near the end of her life. (D. 1892)

“It is an interesting and demonstrable fact that all children are Atheists, and were religion not inculcated into their minds they would remain so.”

— Rose, "A Defense of Atheism" speech (1861)

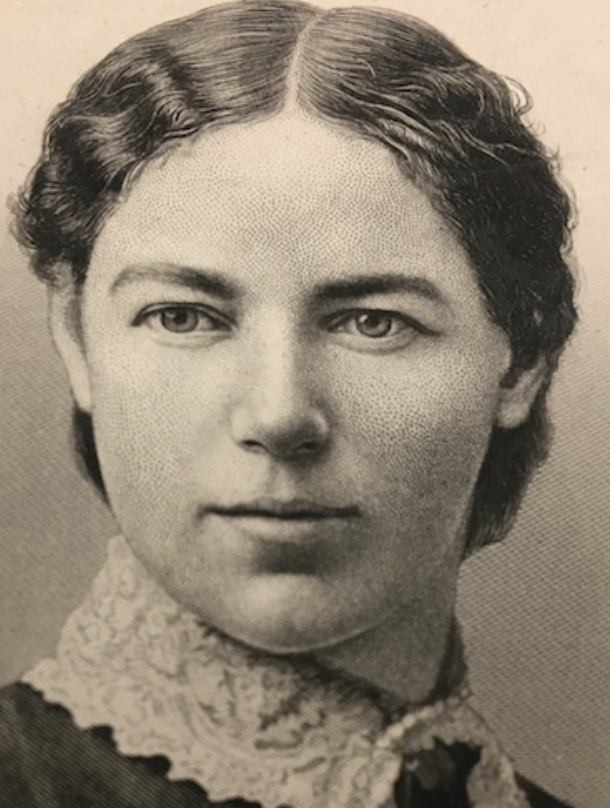

Helen H. Gardener

On this date in 1853, freethinker and suffragist Helen H. Gardener, née Alice Chenoweth, was born in Virginia, the youngest daughter of a Protestant minister who had inherited slaves but freed them in 1853 despite existing legal obstacles. Changing her name in her 30s, she became a writer in New York City, studied biology at Columbia and met “the Great Agnostic” Robert Green Ingersoll, who encouraged her to undertake a lecture series. The lectures were published in 1885 in book form, Men, Women and Gods.

A friend of feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Gardener was a member of Stanton’s Woman’s Bible Committee. Chosen by Stanton to deliver her memorial service, Gardener quipped that while most suffragists found the Woman’s Bible too radical, she found it not radical enough! She also used fiction to crusade for women’s rights, writing novels, for example, showing the harm of the scandalously low age of consent laws of her era.

In her 1885 book Men, Women, and Gods, she wrote: “I do know that women make shirts for seventy cents a dozen in this [world]. I do know that the needs of humanity and this world are infinite, unending, constant, and immediate. They will take all our time, our strength, our love, and our thoughts; and our work here will be only then begun.”

She became vice president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1917, working as chief liaison with President Woodrow Wilson’s administration, and credited with being a “worker of miracles” by sister suffragists. At age 67 she became the first woman appointed to the U.S. Civil Service Commission, serving with distinction for five years.

She died at 72 of myocarditis. She had donated her brain for scientific study before her body was cremated and its ashes interred at Arlington National Cemetery beside the grave of her second husband. Her brain is housed as part of a collection at Cornell University. (D. 1925)

PHOTO: Gardener at age 41.

"I do not know of any divine commands. I do know of most important human ones. I do not know the needs of a god or of another world.”

— Gardener, "Men, Women, and Gods, and Other Lectures" (1885)

Robin Morgan

On this date in 1941, Robin Morgan — feminist author, journalist, editor, lecturer, organizer, atheist and activist — was born in New York City. As she notes in her memoir, Saturday’s Child, “Saturday’s child has to work for a living.” She started at age 2 as a tot model. She had her own radio show by age 4, then acted in the role of Dagmar on the popular series “Mama” in the 1940s and 1950s. She left show biz to write and became a founder and leader of the contemporary feminist movement.

Morgan’s columns and articles for Ms. magazine appeared from 1974-88. She was editor-in-chief of Ms. for four years and later its international consulting editor. Her groundbreaking anthology Sisterhood Is Powerful came out in 1972, followed by Sisterhood Is Global (1984), Sisterhood Is Forever (2003) and Fighting Words: A Toolkit for Combating the Religious Right (2006). Morgan is a distinguished poet and the author of more than 20 books, including her 2006 novel The Burning Time, based on the first witchcraft trial in Ireland.

She has traveled the globe as a feminist activist, scholar, journalist and lecturer. She is a co-founder of the Feminist Women’s Health Network, the Feminist Writers’ Guild, Media Women and the National Network of Rape Crisis Centers. Her timely The Demon Lover: On the Sexuality of Terrorism tells the personal story of her travel to refugee camps in the Middle East, with a post-9/11 introduction and afterword. A recipient of many awards, she was named FFRF’s Freethought Heroine in 2005 and is an honorary director.

She was married from 1962-83 to poet Kenneth Pitchford, a founding member of the Effeminist movement. He and Morgan, who are both bisexual, have a son, musician Blake Morgan.

She was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2010. Instead of curtailing her effectiveness, the diagnosis inspired her to take the lead in creating the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation’s Women and PD Initiative to help women be better served by research, treatment and assistance for their caregivers. Morgan has shared her struggle with the disease by writing and presenting about her experiences at a variety of venues, including her 2015 Ted Talk, viewed over a million times. In 2018 she published Dark Matter: New Poems, which includes the verses from that presentation.

“Religion is not about awe and joy, despite its purported proprietorship of these and its promise to eventually deliver what already lies around us every day, freely available for utter celebration. Religion is about something else. The etymology of the word itself, from the Latin, to being ‘bound by rules.’ Religion is about terror.”

— Freethought Heroine acceptance speech at FFRF's national convention (Nov. 11, 2005)

Aletta Jacobs

On this date in 1854, women’s rights pioneer Aletta Henriette Jacobs was born the eighth of twelve children to Jewish parents in Sappemeer, the Netherlands. Jacobs wanted to be a physician like her father and brother at a time when there were no female doctors in the Netherlands. She was admitted first to Groningen University and then to Amsterdam University as the only woman studying medicine at each institution. She founded the first birth control clinic in the world in Amsterdam in 1882 and earned her doctorate the following year.

In 1884 she married Carel Gerritsen, a feminist and alderman of Amsterdam and member of the Dutch parliament. Since neither were religious, they opted for a civil ceremony, uncommon for the time. She started a medical practice specializing in treating women and children (often treating poor women for free), which she ran for 25 years.

She assembled a library of about 2,000 women’s studies books in German, French, Dutch and English titles — languages she was fluent in — now housed at the University of Kansas. She retired from medicine in 1903, the year Gerritsen died, to devote her life to feminism and pacifism.

Jacobs embarked on a woman’s suffrage world tour with Carrie Chapman Catt in 1911, asserting that suffrage was the most important means for women’s emancipation. She headed the Dutch Woman Suffrage Association, founded in 1894, and often participated in the International Women’s Suffrage Alliance, presided over by Catt. By the time her memoir was published in 1924, women had gained the right to vote in Holland and many other European countries.

In a letter Jacobs wrote to Catt in 1928, the year before her death, she said: “My dear Carrie, I feel sure we have not lived for nothing. We have done our task and we can leave the world with the conviction that we have left it in a better condition than we have found it.” (D. 1929)

“As a freethinker, she belonged to no organized religious community and disliked religion of any kind.”

— Harriet Feinberg, editor of Jacobs' memoir "Memories: My Life as an International Leader in Health, Suffrage, and Peace" (1996)

Flo Kennedy

On this date in 1916, lawyer, activist, civil rights advocate and feminist Florynce Rae “Flo” Kennedy was born in Kansas City, Mo., to parents Wiley and Zella Kennedy. The second of five daughters, Kennedy grew up in a mostly white neighborhood, in which her father once stood up to members of the Ku Klux Klan with a shotgun. Kennedy wrote, “My parents gave us a fantastic sense of security and worth. By the time the bigots got around to telling us that we were nobody, we already knew we were somebody.”

Finishing high school at the top of her class in 1934, Kennedy opened a hat shop, performed on a radio show and operated an elevator. Her first political protest involved helping to organize a boycott when the local Coca-Cola bottler refused to hire black truck drivers. She moved to New York in 1942, graduating from Columbia University in 1948. In 1951 she became the first black woman to graduate from Columbia Law School, where she was admitted after threatening legal action on the grounds of racial discrimination.

Kennedy ran her own law practice, representing the estates of jazz greats Billy Holiday and Charlie Parker and the black power leader H. Rap Brown, among other Black Panthers. Despite tending to take on cases related to feminism and civil rights, Kennedy eventually realized that she needed to employ broader strokes to battle oppression and effect the kind of social change she had in mind. Turning to political activism, Kennedy cofounded the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966. That same year, she established the Media Workshop in an effort to influence the representation of black people in journalism and advertising, threatening boycotts and pickets.

At a 1967 anti-Vietnam War convention in Montreal, her speaking career was launched by a fiery invective against the refusal to allow Bobby Seale to discuss racism. Kennedy became known for her vitriolic tirades and incendiary comments, delivered in her characteristic cowboy hat and boots.

Along with feminism and racial equality, Kennedy also championed gay rights, as well as rights for prostitutes and other minorities. In 1971, Kennedy founded the Feminist Party, nominating Shirley Chisholm, a New York Democrat, for president, and helped to found the National Women’s Political Caucus. She founded the National Black Feminist Organization in 1975. Throughout her life, Kennedy championed pro-choice legislation, organizing a group of feminist lawyers to challenge New York State’s abortion law in 1969, influencing the legislature to liberalize abortion the next year.

With Diane Schulder, she coauthored a book called Abortion Rap in 1971. While Gloria Steinem is often unwittingly credited with the clever slogan, “If men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament,” Flo coined it. The two were warm colleagues, once going on a speaking tour together.

Kennedy was known for her quick repartee. When asked by a male heckler, “Are you a lesbian?” she replied, “Are you my alternative?” Kennedy launched a suit against the Catholic Church in 1968 for spending money illegally to influence abortion legislation, arguing that its campaign violated the separation of state and church. Furthering her efforts to rescind the church’s tax-exempt status in 1972, Kennedy filed tax evasion charges against the church with the IRS. She was briefly married to Charles Dudley Dye in 1957 but he died soon after. D. 2000.

“If men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament.”

— Flo Kennedy, who, with Gloria Steinem, popularized this iconic slogan, repeating a remark made to them both by a woman taxi-cab driver in Boston.

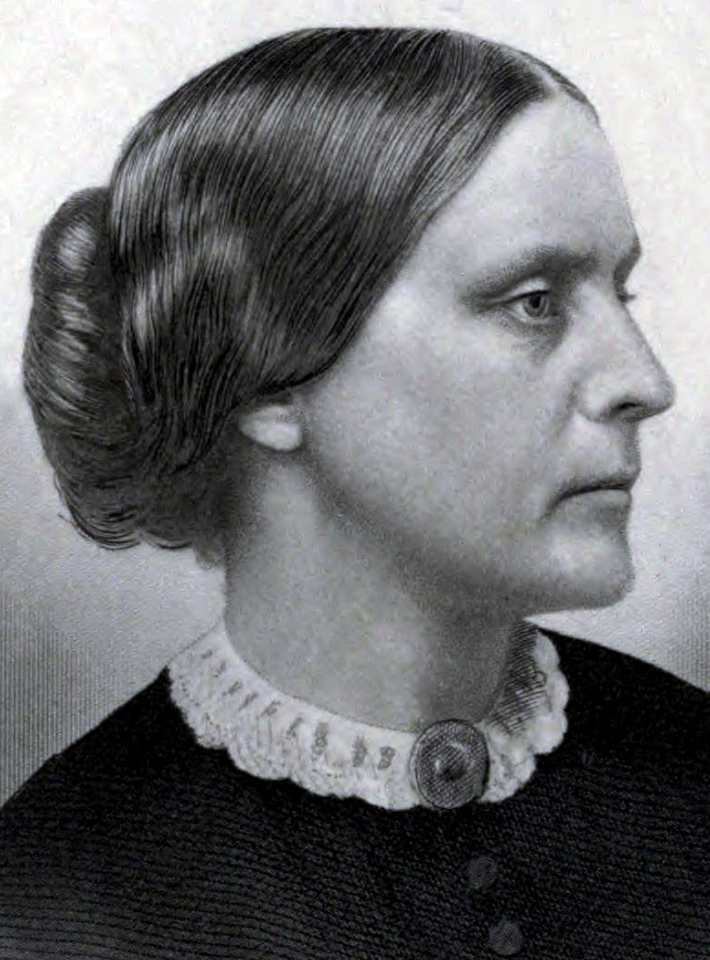

Susan B. Anthony

On this date in 1820, Susan Brownell Anthony was born in Massachusetts. She taught school from ages 15 to 30 before devoting her life to reform. She and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, starting in 1850, became lifelong feminist collaborators. The tireless crusader spent 30 years campaigning for women’s suffrage. Raised Quaker, she became a Unitarian but at the end of her life was an agnostic. Anthony’s professed “creed” was that of “the perfect equality of women,” according to Stanton.

While privately scolding Stanton for editing the controversial Woman’s Bible, Anthony publicly defended her: “I think women have just as much a right to interpret and twist the Bible to their own advantage as men always have interpreted and twisted it to theirs.” (Interview in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, quoted in The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony.) She also confessed, “But while I do not consider it my duty to tear to tatters the lingering skeletons of the old superstitions and bigotries, yet I rejoice to see them crumbling on every side.”

Her biographer Ida Husted Harper wrote that after Anthony visited a poor mother of six in Ireland in 1883, Anthony noted that “the evidences were that ‘God’ was about to add a No. 7 to her flock” and later commented, “What a dreadful creature their God must be to keep sending hungry mouths while he withholds the bread to fill them!”

There is no record she ever had a serious romance despite receiving marriage offers and would answer journalists’ questions with statements like “It always happened that the men I wanted were those I could not get, and those who wanted me I wouldn’t have.” To another she answered, “I never found the man who was necessary to my happiness. I was very well as I was.” She had no desire to “give up my life of freedom to become a man’s housekeeper.”

But according to Sted Mays, writing in the Gay & Lesbian Review, Anthony felt compelled to create a conventional public persona and made excuses for her unmarried status in order to hide her same-sex attractions: “She talked in interviews about not wanting to be trapped in a male-dominated relationship. But the real reason she never had a serious relationship with a man was that her passions were directed toward other women.” (“Stop Straightwashing Susan B. Anthony,” Feb. 10, 2020)

She died of heart failure at age 86 at her home in Rochester, N.Y. (D. 1906)

“I could not dash her faith with my doubts, nor could I pretend a faith I had not; so I was silent in the dread presence of death.”

— Anthony contemplating her sister on her deathbed, "The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, Vol. 2" by Ida Husted Harper (1898)

Josephine K. Henry

On this date in 1846, Josephine Kirby Henry, née Williamson, was born into a wealthy family in Newport, Kentucky. She was 15 when her family moved to Versailles. She gave piano lessons and taught at the Versailles Academy for Ladies. In 1868 she married William Henry, who had served as a captain in the Confederate Army.

Henry was the first woman in the South to run for state office as a candidate of the Prohibition Party for clerk of the Court of Appeals in 1890, receiving nearly 5,000 votes in the notoriously anti-suffrage state. Kentucky was the last state in the union to grant women such basic rights as property ownership, guardianship of their children and the right to make a will. Henry was credited as the main force behind the adoption of the 1894 Woman’s Property Act, garnering 10,000 signatures.

Serving on the revising committee of Elizabeth Cady Stanton‘s The Woman’s Bible, Henry submitted two letters which were published in the appendix. For this heresy, she was declared an “undesirable member” of the Kentucky Equal Rights Association. Henry wrote a 30-page booklet, “Woman and the Bible” (1905), followed by a critique of the treatment of women in the institution of marriage: “Marriage and Divorce” (c. 1907).

She died in Versailles after suffering a stroke at age 84. (D. 1928)

"Is not the Church today a masculine hierarchy, with a female constituency, which holds woman in Bible lands in silence and in subjection? No institution in modern civilization is so tyrannical and so unjust to woman as is the Christian Church. It demands everything from her and gives her nothing in return."

— from Henry's 1897 letter responding to Frances Willard's praise of "The Woman's Bible"

Sonia Johnson

On this date in 1936, Sonia Ann Johnson, née Harris, was born a fifth-generation Mormon in Malad, Idaho. She graduated from Utah State University and married Rick Johnson, then pursued her M.A. and Ed.D. degrees from Rutgers University. She taught English at American and foreign universities, working part-time as a teacher while accompanying her husband on overseas jobs.

The family returned to the U.S. in 1976, buying a house in Virginia, one of the states that had not ratified the Equal Rights Amendment. Johnson became such an ardent supporter of the ERA that she was excommunicated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1979. She exposed the role of the wealthy Mormon Church in sabotaging passage of the ERA. She went on a 37-day hunger strike in the Illinois statehouse in 1982 during the last days of the ERA countdown to symbolize how “women hunger for justice.”

Johnson ran on a feminist ticket for U.S. president in 1984 as the candidate of the Citizens Party, becoming the first third-party candidate to qualify for primary matching funds. In countless speeches, she pointed out, “Nobody’s ever fought a revolution for women.” She wrote eloquently of her experiences in From Housewife to Heretic (1981). In a 1982 speech to the Freedom From Religion Foundation, she said, “I have to admit that one of my favorite fantasies is that next Sunday not one single woman, in any country of the world, will go to church. If women simply stop giving our time and energy to the institutions that oppress, they would have to cease to do so.”

Her marriage ended amid tensions around her ERA advocacy and she started a feminist collective in an old monastery near Albuquerque, N.M. Membership dwindled until only she and Jade DeForest were left. They moved to Arizona and have been together ever since, according to a news story in the Salt Lake Tribune (Jan. 19, 2019).

Johnson, who is estranged from her four children, last published a book in 2010, The SisterWitch Conspiracy.

“Did I believe in God? The answer was no. All my conventional beliefs fell off me like a big, sloppy, unnecessary overcoat, and my real self emerged."

— Johnson, on leaving Mormonism behind, Salt Lake Tribune interview (Jan. 19, 2019)

Nuala O’Faolain

On this date in 1940, Irish journalist, memoirist and feminist Nuala O’Faolain (pronounced oh-FWAY-lawn) was born in Dublin, the second of nine children. Her unhappy childhood, lacking in love, inspired much of her later writing. Her father wrote a newspaper column for the Dublin Evening Press and, according to O’Faolain, spent many nights out in Dublin with little regard for his family. Her mother “sank into despair and alcoholism” as a result. (The New York Times, May 11, 2008.)

O’Faolain attended a Catholic convent school but was expelled for unruly behavior. She studied English at University College in Dublin and medieval English literature at the University of Hull in England. She earned a B.Phil. in English from Oxford in the 1960s. After her studies, she lectured in the English department at University College and then moved to London, where she established a broadcasting producer career with the BBC.

In 1977 she returned to Ireland to produce television programs, often with feminist content about Irish women. In 1986 she started writing a weekly column for the Irish Times. Her first memoir, Are You Somebody? (1996), won her international recognition. Following were successful novels, My Dream of You (2001) and The Story of Chicago May (2006). In 2003, Almost There, a sequel to her first memoir, was published.

O’Faolain had a 15-year relationship with the feminist journalist and playwright Nell McCafferty. She died in 2008 in Dublin from lung cancer at age 68. In an interview after her terminal diagnosis, O’Faolain stated she did not believe in an afterlife. (The Independent, interview with Marian Finucane, April 13, 2008). Her May 11 obituary in The Guardian stated, “The long and illustrious list of women who challenged the status quo — and changed Irish society in the process — had no more eloquent an exponent than Nuala O’Faolain.”

Nuala O'Faolain: And though I respect and adore the art that arises from the love of God and though nearly everybody I love and respect themselves believes in God, it is meaningless to me, really meaningless.

Marian Finucane: The reason I asked you is because it is a source of comfort for many people.

O'Faolain: Well, I wish them every comfort, but it is not even bothering me. I don’t even think about it. I have never believed in the Christian version of the individual creator.— O'Faolain interview, The Independent (April 13, 2008)

Marilla Ricker

On this date in 1840, Marilla Marks Ricker (née Young) was born in New Durham, New Hampshire. She became a trail-blazing attorney, abolitionist, humanitarian and suffragist. Her father, Jonathan Young, reportedly related to Mormon prophet Brigham Young, was a freethinker and proponent of women’s rights who took her to courtrooms and town meetings.

As a child she witnessed a “fiery” sermon about hell at her mother’s Free Will Baptist church, she later wrote. (Boston Business Folio, 1895.) “Do you wonder that I, a child of ten years, said to my father, who was a freethinker, infidel, atheist, or whatever else you please to call him: ‘I hate my mother’s church. I will not go there again.’ “

She started teaching at age 16, refusing to read from the bible during class, instead preferring literary works, including those of Emerson. When the school committee told her bible reading was mandatory, she refused to comply and left the profession.

In 1863 she married John Ricker, a man 33 years her senior. He died five years later, leaving an estate that made her financially independent. She studied law in Washington, D.C., determined to help the downtrodden. She passed the bar with the highest grade of anyone admitted in 1882. Her first public courtroom appearance was as assistant counsel to Robert G. Ingersoll and became known as the “prisoner’s friend,” successfully challenging a district law that indefinitely confined poor criminals unable to pay fees.

Ricker in 1871 had the distinction of being the first U.S. woman to vote using the argument that women were “electors” under the Fourteenth Amendment. In 1890 she won the right of women to practice law in New Hampshire. She was admitted to the U.S. Supreme Court bar in 1891. She was denied the right to run for governor of New Hampshire in 1910 on a woman’s rights platform by the state attorney general. Her books include The Four Gospels (1911), I Don’t Know, Do You? (1916) and I Am Not Afraid, Are You? (1917).

In I Am Not Afraid she wrote: “A religious person is a dangerous person. He may not become a thief or a murderer, but he is liable to become a nuisance. He carries with him many foolish and harmful superstitions, and he is possessed with the notion that it is his duty to give these superstitions to others.” (D. 1920)

“A steeple is no more to be excluded from taxation than a smoke stack.”

— Ricker, "I Am Not Afraid, Are You?" (1917)

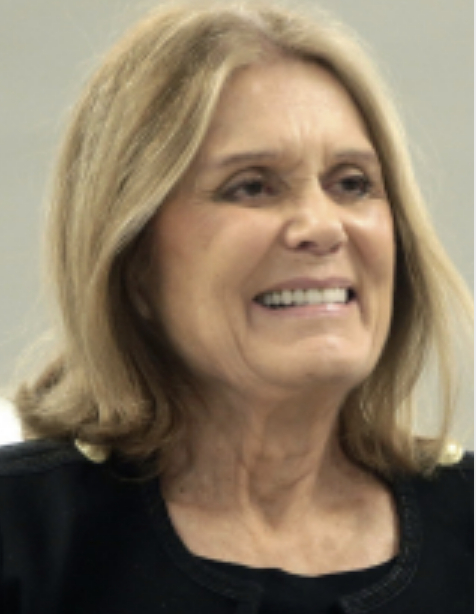

Gloria Steinem

On this date in 1934, feminist leader and journalist Gloria Steinem was born in Toledo, Ohio, to Leo and Ruth (Nuneviller) Steinem. Her father abandoned the family when she was 10, leaving her to care for her mother, who was dysfunctional from depression. She went to school when possible, tap-danced in talent contests and mothered her mother. In 1951 she moved in with her older sister in Washington, D.C., and completed her high school education. She was accepted by Smith College, where she first started to write, and graduated magna cum laude in 1956.

The recipient of a two-year grant to India, she discovered that she was pregnant. During a stopover in England en route to India and facing a desperate crossroads, Steinem managed to arrange an abortion. She was later on the vanguard of those calling for legalized abortion. She moved in 1960 to New York City to start a journalism career, where she was met with sexist roadblocks such as the Life magazine editor who told her “We don’t want a pretty girl. We want a writer.”

In 1969 Steinem wrote her first feminist article. Throughout the next five years, she stumped for feminism around the country, becoming the women’s movement’s best-known, most quotable exponent. She helped found Ms. Magazine in 1971, convinced that freedom would come through “individual women telling the truth.” She defined feminism as “the belief that women are full human beings.”

In 1972, McCall’s magazine named her Woman of the Year. She was an influential participant at the National Women’s Conference in Houston in 1977, a landmark gathering. “Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions,” her first collection of essays and articles, was published in 1983. She also wrote “Marilyn: Norma Jeane” (1986), a biography of Marilyn Monroe, “Revolution From Within: A Book of Self-Esteem” (1992) and “Moving Beyond Words” (1997). An idea generator and original thinker, Steinem remains one of feminism’s most elegant, loyal and thoughtful advocates.

PHOTO: Steinem speaking at the Women Together Summit at Carpenters Local Union in Phoenix in 2016. Gage Skidmore photo under CC 2.0.

"It’s an incredible con job, when you think of it, to believe something now in exchange for life after death. Even corporations, with all their reward systems, don’t try to make it posthumous."

— Steinem, interview with Annie Laurie Gaylor, The Feminist Connection (November 1980)

Matilda Joslyn Gage

On this date in 1826, suffragist Matilda Electa Gage (née Joslyn) was born in Cicero, N.Y. Her father was Dr. Hezekiah Joslyn, whose home was a station on the underground railroad and who advocated for abolition of slavery, women’s rights, freethought and temperance. She married merchant Henry Gage at age 18 and gave birth to five children, one of whom died in infancy.

A founding member and later president of the National Woman Suffrage Association, Gage expressed indignation over “the wrongs inflicted upon one-half of humanity by the other half in the name of religion.” She delivered a major address, “Woman, Church, and State,” at a suffrage convention in 1878. By popular response, she later turned this address into a book of the same name in 1893. It documented woman-hating abuses ranging from celibacy to witch hunts that stemmed from religious doctrines.

Gage convened the historic Woman’s National Liberal Union in 1890, the first feminist group devoted to the promotion of the separation of church and state. Her warning of a union of Catholics and Protestants whose agenda was to put God in the Constitution and attack secular schools, is eerily timely today: “[I]n order to help preserve the very life of the Republic, it is imperative that women should unite upon a platform of opposition to the teaching and aim of that ever most unscrupulous enemy of freedom — the Church.”

She died in Chicago at age 71. Carved on her tombstone in Fayetteville, N.Y., is her well-known motto: “There is a word sweeter than Mother, Home, or Heaven; that word is Liberty.” (D. 1898)

"During the ages, no rebellion has been of like importance with that of Woman against the tyranny of the Church and State; none has had its far reaching effects. We note its beginning; its progress will overthrow every existing form of these institutions; its end will be a regenerated world."

— "Woman, Church, and State" by Matilda Joslyn Gage (1893)

Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon

On this date in 1827, Barbara Leigh Smith (later Bodichon) was born in England. Her father was a dissenter, Universalist and benefactor to the poor. He had five children with a young milliner whom he never married, possibly out of principle. Barbara’s working class mother died young. The children grew up in an egalitarian home and Barbara received an inheritance at 21, just like her brothers. No college admitted women at the time, but she and a female friend took an unprecedented walking tour of Europe unchaperoned.

Barbara was a lifelong friend of novelist and freethinker George Eliot, who modeled “Romola” after her, and associated with many artists and intellectuals, including freethinker G.J. Holyoake. Barbara’s cousin Florence Nightingale snubbed her, evidently because of her “illegitimate” status. In 1854 she wrote a summary of laws concerning women, which became a major catalyst of the British feminist movement and resulted in the adoption of the Married Women’s Property Bill in 1857. She also petitioned Parliament for suffrage and was instrumental in the founding of Girton College in 1869, which admitted women. D. 1891.

“There was hardly a scheme for the furtherance of women's interests that did not bear the imprint of her driving aspirations. The only exception lay in projects sponsored by any branch of Christianity, for though she was not an atheist she had her own reasons for keeping her distance from organised religion. 'Ah! If you were only like Miss Barbara Smith!' Dante Gabriel Rossetti wrote to his pious and retiring sister Christina.”

— Literary critic Dinah Birch, commenting on Bodichon, London Review of Books (October 1998)

Mary Wollstonecraft

On this date in 1759, feminist author Mary Wollstonecraft was born in London, the second of seven children. An industrious young woman, she worked as a governess and then opened her own school. Her first book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, was published in 1786, followed by a novel, a children’s book, a translation and The Female Reader (1789).

When Edmund Burke read her review of a sermon by dissenting minister Richard Price, he wrote a famous attack on the American and French revolutions. Wollstonecraft rebutted his polemic in her 1790 pamphlet “A Vindication of the Rights of Men, in a Letter to the Right Honourable Edmund Burke; Occasioned by His Reflections on the Revolution in France,” attacking the aristocracy and advocating for republicanism.

Her seminal A Vindication of the Rights of Woman was published in 1792. The first influential book calling for the equality of the sexes, it urged that women be educated and treated as “rational creatures.” Wollstonecraft championed dress reform, breast-feeding, early education and a national system of co-educational primary schools. She warned of those who prey “on the credulity of women.”

She gave birth to a daughter after a brief liaison with Gilbert Imlay, an American businessman, then married atheist William Godwin in March 1797. After an uneventful pregnancy, 38-year-old Mary gave birth on Aug. 30, 1797 to a second daughter, Mary, then died of an infection 10 days later. Wollstonecraft was an ardent rationalist and deist who adopted an agnostic point of view toward the end of her life. Her daughter Mary ran off as a teenager with poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and wrote Frankenstein at age 19. (D. 1797)

“Besides, in great schools, what can be more prejudicial to the moral character than the system of tyranny and abject slavery which is established amongst the boys … which makes religion worse than a farce.”

— Wollstonecraft, "A Vindication of the Rights of Woman" (1792)

Margaret Fuller

On this date in 1810, Margaret Fuller was born in Massachusetts, the first of nine children. Fuller became one of the foremost 19th-century women writers and critics. When her father died in 1835, she assumed financial headship of the family, teaching at Bronson Alcott’s Temple School. She translated Goethe and became editor of the Transcendentalist publication The Dial for two years under Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Her first book, Summer on the Lakes, was published in 1844, in which she observed the missionary harm to native Americans in the Midwest. At age 34, she became the first woman staff member of the New York Tribune, opening the doors of journalism to women and often writing of women’s needs.

Woman in the Nineteenth Century, in the vein of Mary Wollstonecraft‘s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, came out in 1845: “Women are, indeed, the easy victims both of priestcraft and self-delusion; but this would not be, if the intellect was developed in proportion to the other powers.” As a foreign correspondent for Horace Greeley, Fuller traveled to Europe, where she befriended Italian republican revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini.

Living in Rome, she met a handsome younger nobleman. They married secretly and had a son in 1848. When the republican cause was lost, they sailed to America, and were tragically drowned in a shipwreck on July 19, 1850, 50 yards from shore.

Her Memoirs, published posthumously, was bowdlerized by the Unitarian minister William Henry Channing, who put them together, according to biographer Bell Gale Chevigny. Chevigny documented pious salutations, such as “O Father,” inserted into Fuller’s words to soften irreverencies. Chevigny’s book, The Woman and the Myth, Margaret Fuller’s Life and Writings, restores Fuller’s original words. A possible Deist at most, Fuller wrote in 1842: “You see how wide the gulf that separates me from the Christian Church.” (D. 1850)

"Give me truth; cheat me by no illusion."

— Fuller, credo from "Memoirs," posthumously published in 1852 by Ralph Waldo Emerson, W.H. Channing and J.F. Clarke

Wafa Sultan

On this date in 1958, Wafa Sultan was born in Banias, Syria. Sultan received her degree in medicine at the University of Aleppo, where she says she lost her faith in Islam after seeing one of her professors gunned down by the Muslim Brotherhood. In 1989 she and her husband emigrated to Los Angeles with their children.

Sultan has written essays critical of Islam, some published on the reform website Annaqed (The Critic). In 2005, Sultan gained notoriety for her appearance on Al Jazeera debating a Muslim cleric and asking, “Why does a young Muslim man, in the prime of life, with a full life ahead, go and blow himself up? In our countries, religion is the sole source of education and is the only spring from which that terrorist drank until his thirst was quenched.”

In 2009 she published her first book in English, A God Who Hates: The Courageous Woman Who Inflamed the Muslim World Speaks Out Against the Evils of Islam. She describes herself as a cultural Muslim. In 2006 she received FFRF’s Freethought Heroine Award.

“I receive too many emails from women in the Islamic world, telling me: ‘Go ahead, we are behind you,’ but unfortunately they’re afraid for their lives.”

— Sultan, speaking to FFRF's 2006 national convention

Mary Morain

On this date in 1911, Mary Stone Dewing Morain was born in Cambridge, Mass. She studied social work and therapy and earned her master’s degree from the University of Chicago. Morain spent time as president of the International Society for General Semantics and was a member of its board of directors and executive committee.

Morain served on the birth control boards in Massachusetts and California in the 1940s and 1950s and supported Planned Parenthood. She married Lloyd Morain in 1946. She devoted much of her life to popularizing humanism and supporting worldwide humanist organizations. In 1954 she and Lloyd published Humanism As the Next Step, which explained the basics of humanism. She and Lloyd founded the International Humanist and Ethical Union in 1952. In 1994 they won the American Humanist Association’s Humanist of the Year Award jointly.

She died in 1999 after contracting pneumonia.

"Believing that we exist only in a single world, the natural world that we share with other living creatures, and that we have no special first-class tickets that allow for travel to continuous existence in other spheres at the end of our journey in this life. In our human distresses, we have only each other to turn to for help."

— Morain, 1994 Humanist of the Year acceptance speech

Barbara G. Walker

On this date in 1930, Barbara G. Walker was born in Philadelphia. In early childhood, she had her first disappointment with religion, when a minister told her that her deceased pet dog wouldn’t go to heaven. She threw an uncharacteristic tantrum, telling him: “I don’t want anything to do with your rotten old God and nasty old heaven.” First reading the King James bible as a young teenager, she decided: “It sounded cruel. A God who would not forgive the world until his son had been tortured to death — that did not strike me as the kind of father I would want to relate to.”

She majored in journalism at the university of Pennsylvania, married research chemist Gordon Walker and moved to Washington, D.C., where she worked at the Washington Star. Relocating to Morristown, New Jersey, she taught the Martha Graham dance technique. She is a knitting expert, writing 10 volumes, including the classics Treasury of Knitting Patterns and A Second Treasury of Knitting Patterns. In the mid-1970s she became part of the “new feminist wave,” writing the monumental feminist/freethought sourcebook, The Woman’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets (1983). Her many other books include The Skeptical Feminist (1987), Man Made God: A Collection of Essays (2010) and Belief and Unbelief (2014). An atheist, she has also specialized in debunking irresponsible, New Age assertions about crystals.

"[T]he very fears and guilts imposed by religious training are responsible for some of history’s most brutal wars, crusades, pogroms, and persecutions, including five centuries of almost unimaginable terrorism under Europe’s Inquisition and the unthinkably sadistic legal murder of nearly nine million women. History doesn’t say much very good about God."

— Walker, acceptance speech for the 1993 Humanist Heroine award from the Feminist Caucus of the American Humanist Association

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

On this date in 1860, Charlotte Perkins Gilman was born in Hartford, Conn. A poet, author, editor and theorist, Gilman became one of the most celebrated feminists of her day. Her father, who virtually abandoned the family, was the grandson of evangelist Lyman Beecher. She educated herself, embracing daily exercises and eschewing corsets. She married artist Charles Walter Stetson when she was 23. She suffered paralyzing depression brought on after giving birth in 1885 to her daughter Katherine. It’s detailed in her 1890 classic story “The Yellow Wallpaper.”

After separating from her husband, she launched a career as lecturer, journalist and author. Her collection of poems, In This Our World (1893), includes a poem “To the Preacher,” which jeers: “Preach about yesterday, Preacher! … Preach about the other man, Preacher!/Not about me!” When she attended her first National American Woman Suffrage Association convention in 1896, a sister feminist wrote that Gilman had “originality flashing from her at every turn like light from a diamond.” She defended Elizabeth Cady Stanton‘s Woman’s Bible when the delegation passed a resolution against it. Woman and Economics (1898) made her an international figure.

Her thoughts on race were less than enlightened. In “A Suggestion on the Negro Problem” in the American Journal of Sociology in 1909, she wrote, “We have to consider the unavoidable presence of a large body of aliens, of a race widely dissimilar and in many respects inferior, whose present status is to us a social injury. If we had left them alone in their own country this dissimilarity and inferiority would be, so to speak, none of our business. There are other races, similarly distinguished, whose special standing in racial evolution does not embarrass us; but in this case it does.” According to biographer Cynthia Davis, Gilman once said on a trip to London, “I am an Anglo-Saxon before everything” and claimed that non-British immigrants to America were diluting the nation’s reproductive purity.

Other nonfiction included Concerning Children (1901), Human Work (1904), The Man-Made World; or, Our Adrocentric Culture (1911), and His Religion and Hers: A Study of the Faith of Our Fathers and the Work of Our Mothers (1923). In that work, she called for a religion free of patriarchy and wrote, “One religion after another has accepted and perpetuated man’s original mistake in making a private servant of the mother of the race.” In one of her poems she wrote, “What you think may guide our acts / But it does not alter facts.” She once asked,”What glory was there in an omnipotent being torturing forever a puny little creature who could in no way defend himself?”

She found happiness in her 35-year marriage to George Houghton Gilman and wrote her autobiography, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, in 1935. That year Gilman, a firm believer in euthanasia, took her own life using chloroform when pain from inoperable breast cancer became unbearable. (D. 1935)

Preach about the other man, Preacher!

The man we all can see!

The man of oaths, the man of strife,

The man who drinks and beats his wife,

Who helps his mates to fret and shirk

When all they need is to keep at work —

Preach about the other man, Preacher!

Not about me!— From Gilman's poem "To the Preacher" in the collection "In This Our World" (1893)

Sherry Matulis

On this date in 1931, Sherry Matulis was “born an atheist (aren’t we all?),” she mused, in the small town of Nevada, Iowa. “You couldn’t go out to play hopscotch or kick-the-can without tripping over a church or two. (Or a tavern. The churches had a reciprocal arrangement, I think),” she wrote in a column for The Feminist Connection. “But tripping over all those churches wasn’t the real problem. The real problem was all that time spent inside them — skipping over the facts of reality.” (Oct. 24, 1981, speech to the FFRF national convention in Louisville, Ky.)

At age 20 she was surprised to find herself in the first Miss Universe contest, selected by photographs submitted by her husband. As the “village atheist” in Peoria, Ill., Matulis ran small businesses for many years and had five children. A poet and writer, she became a national spokesperson for abortion rights in the 1980s, when she wrote about her life-threatening experience in seeking an illegal abortion in Peoria in 1954. She was invited to speak about her experiences before a U.S. Senate subcommittee chaired by Orrin Hatch in 1981 and testified before several state legislatures.

A firm atheist, she appeared on many radio and national TV programs. Her articles, stories and poetry have been published in such periodicals as Redbook, Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, Questar, Analog, Freethought Today and The Rationalist. She received many awards for her work to protect abortion rights, including from the American Humanist Association and the National Organization for Women. (D. 2014)

Religion’s Child

Aware of light and yet condemned to grope

Through dark regression’s cave, told she must find

Life’s purpose in that blackness, without hope,

Denied the luminescence of her mind

Until, at last, she finds the darkness kind,

Religion’s child — a babe once bright and fair,

Curls up, tucks in her tail, and says her prayer.— Matulis, "Women Without Superstition," ed. Annie Laurie Gaylor (1997)

Helen Taylor

On this date in 1831, Helen Taylor was born in England. Her mother married John Stuart Mill in 1851. When her mother died seven years later, she took care of her esteemed stepfather and assisted Mill in writing his landmark Subjection of Women (1869). After his death in 1873, Taylor edited his Autobiography and Essays on Religion (1874). She was elected to the London School Board three times between 1876 and 1882 and championed disadvantaged children.

She agitated for abolition of school fees and for subsidized school meals and worked to stop abuses at industrial schools. In 1881 she joined the Social Democratic Federation, known as Britain’s first organized socialist political party. Taylor, a strong feminist and suffragist, attempted to run for Parliament in 1885 but her nomination papers were refused. (D. 1907)

"Religion should be taught by ministers of religion or by volunteer teachers, such as teachers of Sunday schools, and … the school master ought not to undertake the work of the clergyman, least of all when we have a church, the richest in the world, magnificently endowed to do its own work."

— Helen Taylor (attributed, 1876)

Meg Bowman

On this date in 1929, Margaret “Meg” Bowman was born in Rugby, North Dakota, to Hazel Whiting and Albert Gunnerud, “pillars” of the Methodist Church. She found one other avid reader in her small town who became her best friend and an atheist like her. After graduating from high school in Illinois, she moved to Arizona, where she married Richard Turner and raised three sons, two of whom preceded her in death.

Bowman became active with the Progressive Party in 1948, earned her B.A. from Colorado College in 1954, a master’s from Arizona State University in 1961 and was awarded a Ph.D. in 1985.

She organized the Fremont, Calif., Human Rights Commission in the 1960s and regularly participated in civil rights and peace marches. She has been active in the Fremont Unitarian Fellowship, the area chapter of National Organization for Women, the San Jose Unitarian Church, the Older Women’s League and at one time co-chaired the Feminist Caucus of the American Humanist Association.

Bowman took part in “burnt offerings” protests in the mid-’70s. A women’s group at St. Clement’s Episcopal Church in New York City first came up with the idea. They rewrote the liturgy from the Book of Common Prayer, read sexist statements from the bible, brought them to the altar and set them on fire. In 1972 at the Democratic National Convention, women repeated the ritual on the streets of Miami Beach. “From Berkeley to Boston, Maine to Miami, we have burned,” Bowman wrote. “Omaha women drew the biggest audiences as they ignited the streets of Nebraska. And, yes, radical feminism has even ‘played in Peoria’ — pyromaniacally.”

Starting in 1986, Bowman helped sponsor impoverished young women through school in Kenya and Romania. She retired from the San Jose State University sociology department. She has written many books through Hot Flash Press, including Memorial Services for Women and Feminist Classics: Women’s Words that Changed the World. An intrepid world traveler, she has organized many international tours with a feminist and freethought slant. In 2010 she accepted the Humanist Heroine award from the American Humanist Association.

She died at age 91 in San Jose, Calif. (D. 2020)

“Why burn? The answer is simple. Read the Bible — the Koran — the theologians and philosophers of the world. Look in your hymnals and then ask, ‘What better way to raise the religious consciousness of obtuse, callous, sexist societies?’ "

— Bowman, explaining the 'burnt offerings" ceremonies organized by U.S. feminists in the 1970s. ("Why We Burn: Sexism Exorcised," 1988)

Clara Bewick Colby

On this date in 1846, Clara Dorothy Bewick (later Colby) was born in Cheltenham, England. She moved with her parents when she was 8 to a farm near Windsor, Wis. As an early reader, she liked to memorize and recite and churned butter by keeping time to fearful hymns threatening “the hells of fire,” she recalled in a lecture. At 19, she moved to Madison and enrolled at the University of Wisconsin. Graduating in 1869 as valedictorian, she was instrumental in opening admission of the UW to women.

She taught history and Latin at the UW, then married Leonard Wright Colby in 1871 and moved to Beatrice, Nebraska. She served for 16 years as president of Nebraska’s Woman’s Suffrage Association. She founded The Woman’s Tribune in 1883 and published that organ of the National Woman Suffrage Association for 25 years, including daily editions through the suffrage conventions. As editor she also set type, was compositor and sometimes ran the press.

Legendary for her energy and work ethic, Colby and her husband adopted two children, including a Lakota Sioux infant, “Lost Bird,” found by Leonard in the arms of the girl’s slaughtered mother after Wounded Knee. Her husband later abandoned the family with the child’s nursemaid and they divorced in 1906. Colby raised the child by herself.

Colby was the first woman designated as a war correspondent during the Spanish-American War. She lectured in nearly every state for suffrage, as well as England, Ireland and Scotland. Colby belonged to the Congregational Church but introduced and defended resolutions denouncing patriarchal religious dogma, notably at the 1885 woman suffrage convention. She routinely featured her friend Elizabeth Cady Stanton‘s critiques of religion on the front pages of The Woman’s Tribune.

She died at age 70 of pneumonia and myocarditis in Palo Alto, Calif., and her ashes are buried in the Congregationalist cemetery near her childhood home in Windsor, Wis. (D. 1916)

Lillie Devereux Blake

On this date in 1833, Lillie Devereux Blake, née Elizabeth Johnson Devereux, was born into a wealthy family in Raleigh, North Carolina. The famous beauty came into money as a young woman and married a handsome attorney in 1855, who freely spent her fortune before shooting himself in 1858. Blake, as the young mother of two daughters, had to turn her “scribbling” into a way to support her family with her pen.

In 1861, then living in New York City, she became a war correspondent. By 1882, 500 of her stories, articles, speeches and lectures, plus five novels, had been published. She earned about $3,600 over a lifetime of writing, often under the pen name Tiger Lily.

At 35 she turned her energies almost exclusively toward working for women’s rights. Protesting Columbia University’s exclusion of women on behalf of her daughters, she could not budge the opposition of Dr. Morgan Dix, rector of Trinity Church in New York City. In 1883 she encountered her theological foe again when he embarked on an anti-suffrage lecture series. Blake responded immediately by scheduling her own lectures, including one on “Woman in Paganism and Christianity.” Dix, she said, was “a theological Rip Van Winkle, who has slept, not 20 but 200 years.”

She campaigned for the rights of women prisoners (“Is it a crime to be a woman?”), and achieved many reforms. A good friend of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, she served on The Woman’s Bible revising committee. For 11 years she ran the successful New York State Suffrage Association, defeating an anti-suffrage governor, winning the right to vote for rural women at elections of school trustees and getting women accepted as census takers. (D. 1913)

"Every denial of education, every refusal of advantages to women, may be traced to this dogma [of original sin], which first began to spread its baleful influence with the rise of the power of the priesthood and the corruption of the early Church."

— Blake, "Woman's Place To-Day: Four Lectures in Reply to the Lenten Lectures on 'Woman' by the Rev. Morgan Dix, Rector of Trinity Church, New York" (1883)

Maria Deraismes

On this date in 1828, Maria Deraismes was born in Paris into a prosperous, middle-class family. She was given more educational opportunities than most young women of her era. She wrote a collection of dramatic sketches that were published in 1861, then turned her hand to comedies. She became one of the founding members of the feminist movement in France. Deraismes welcomed participants to the first French Women’s Congress, held in 1878, and was president of the Society for the Improvement of the Condition of Women.

She made a famous rebuttal to the misogynist labeling of women intellectuals as “bluestockings.” A rationalist, she was the first woman Freemason in France and directed several freethought societies. She was a co-presider of the Anti-Clerical Congress in Paris in 1881.

She died at age 65 in Paris, where a street is named after her as well as the town square in St. Nazaire. (D. 1894)

Barbara Ehrenreich

On this date in 1941, author Barbara Ehrenreich was born in Butte, Montana. She graduated from Reed College in 1963 and earned her Ph.D. at Rockefeller University in 1968, working in the field of science, then turning to writing. Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers (1972), co-written with Deirdre English, was a widely acclaimed exposé of male domination of female health care. Her essays are regularly featured in mass-circulation periodicals such as The Nation, Ms., Mother Jones, Esquire, Vogue and The New York Times Magazine.

For many years she was a regular columnist for Time. Other books include For Her Own Good: One Hundred Fifty Years of the Experts’ Advice to Women (with Deirdre English, 1978), The Hearts of Men (1983), The Worst Years of Our Lives (1990) and the classic exposé Nickel and Dimed: On Not Getting By in America, in which she went undercover as a waitress and member of the working-class poor. Her classic article, “U.S. Patriots: Without God on Their Side,” originally appeared in Mother Jones, February/March 1981, and is reprinted in the anthology Women Without Superstition.

In an essay for The New York Times Magazine, Ehrenreich proudly described her family as “the race of ‘none,’ ” as being “the kind of people … who do not believe, who do not carry on traditions.” She was named a Freethought Heroine by FFRF in 1999. Her acceptance speech was titled “My Family Values Atheism.”

She died of a stroke at age 81 at a hospice facility near her home in Alexandria, Va. (D. 2022)

"In my parents’ general view, new things were better than old, and the very fact that some ritual had been performed in the past was a good reason for abandoning it now. Because what was the past, as our forebears knew it? Nothing but poverty, superstition and grief. ‘Think for yourself,’ Dad used to say. ‘Always ask why.’ "— Ehrenreich, The New York Times Magazine (April 5, 1992)

Patricia Duffy Hutcheon

On this date in 1926, sociologist Patricia Duffy Hutcheon was born in Saskatchewan, Canada. She earned her undergraduate degree in education and history and her Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Queensland, Australia. In early adult life, because of several adverse personal experiences, she became active in promoting women’s rights and equality of the sexes. She married Alexander “Sandy” Hutcheon. She taught sociology at the University of Regina and the University of British Columbia. She was in great demand as a public speaker and became a prominent humanist in the academic world.

Her 1975 textbook, A Sociology of Canadian Education, was the first ever published on that subject and became a classic. She wrote many books, including Leaving the Cave: Evolutionary Naturalism in Social Scientific Thought (1996), Building Character and Culture (1999) and The Road to Reason: Landmarks in the Evolution of Humanist Thought (2001). In later life her studies focused on the trend of tribalism and the dangers it presented for society.

Hutcheon was named Humanist of the Year 2000 by the Canadian Humanist Association and received the Distinguished Humanist Service Award 2001 from the American Humanist Association. She also assisted in drafting the Humanist Manifesto III issued by the AHA in 2003. She was a member of the BC Humanist Association. (D. 2010)

"Only humanism has a planetary perspective already in place. It is up to us to try to persuade the more open-minded members of the world community to join us in rejecting tribalism before it is too late."

— Hutcheon in her essay, "Can Humanism Stem the Rising Tide of Tribalism?"

Claire Eglin Culhane

On this date in 1918, Canadian activist Claire Eglin was born in Montreal to Russian-Jewish immigrants. She and her brother were the only Jewish students at Maisonneuve School, she told an interviewer. “At Christmas time, we were rejected because we didn’t believe in Jesus Christ. At Easter, we were sometimes pelted with rocks because ‘the Jews crucified Christ.’ ” She began her activist efforts as a teenager, helping with relief efforts in Quebec during the Great Depression and protesting to end the Spanish Civil War.

Despite anti-Semitic discrimination and other obstacles, she graduated from high school, learned how to drive, and trained as a nurse. Eglin Culhane also took a business course to work for a family company. She later found consistent employment by specializing in new systems of medical records. She married union organizer Gerry Culhane and they had two daughters. The couple later divorced.

Eglin Culhane established a tuberculosis hospital in Vietnam during the war, picketed on Parliament Hill in Ottawa against the war, staged sit-ins at prison wardens’ offices, hosted a cable TV show called “Instead of Prisons,” and spoke extensively on the subject of prisons as social control. In 1968, she met with Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau to discuss Canada’s involvement in the Vietnam War. She came under police scrutiny and a file on her expanded to several hundred pages, a fact she was proud of.

One of her final public acts was to take sides with Aboriginals in a dispute with local officials at the OKA Reservation in Ontario. She wrote several books, including Barred from Prison (1979) and Why Is Canada in Vietnam? The Truth About Our Foreign Aid (1972). Biographer Mick Lowe’s 1992 book was titled One Woman Army: The Life of Claire Culhane. In her own book, No Longer Barred from Prison: Social Injustice in Canada (1991), she wrote, “We can only proceed, individually and collectively, to make whatever improvements are possible in our respective areas of concern, sustained by the hope that others are doing the same.”

She was inducted into the Order of Canada, the nation’s highest civilian honor. She was also a member of the BC Humanist Association. (D. 1996)

“Once when asked about religion, she replied, ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.’ "

— "A Humanist Portrait: Claire Culhane" by Glenn Hardie, Humanist Perspectives (Spring 2013)

Frances Wright

On this date in 1795, Frances Wright, the first woman to publicly lecture in the United States, was born an heiress in Scotland. An arresting five feet, 10 inches as an adult, Wright influenced fashion of her day with her liberating style of ringlets and later her adoption of “Turkish trousers.” She traveled with her younger sister Camilla to America in 1818. Her play, “Altorf,” was staged to acclaim in New York in 1819, where she shocked society by using her byline as a female author.

Her travel book, Views of Society & Manners in America (1820), caused a sensation in Great Britain and abroad. Freethinker Jeremy Bentham became her mentor and General Lafayette her confidante. Returning at 29 to America, Frances became a U.S. citizen. As an early and passionate abolitionist, she began a noble but ill-fated model communal plantation to educate slaves for freedom at Nashoba, Tenn. They would have no religion but “kind feeling and kind action,” Wright decreed. The experiment unraveled for lack of money.

At 33, Wright launched her speaking career on July 4, 1828, in Cincinnati, seeking to “destroy the slavery of the mind” and counteract the effects of a religious revival on women, as well as the Christian Party in Politics movement. Wright called for the education of women and the rejection of religion. Her historic speaking tour won her adoration from progressives such as the young Walt Whitman, who recalled how “we all loved her: fell down about her.” But press and clergy dubbed Wright “The Red Harlot of Infidelity” and a “voluptuous preacher of licentiousness.”

Wright urged, “Turn your churches into halls of science, exchange your teachers of faith for expounders of nature. … Fill the vacuum of your mind!” Practicing what she preached, she purchased an old church in New York City for $7,000 and renamed it the “Hall of Science.” It opened its doors in April 1829 for lectures, a radical bookstore and at one time offered a health clinic. She and Robert Dale Owen launched The Free Enquirer and the Working Men’s Party, advocating a 10-hour workday, for which she was dubbed a “female Tom Paine” by the mayor of New York.

After an unsuccessful marriage to Frenchman Phiquepal D’Arusmont, resulting in the birth of a daughter, Wright returned to the U.S., where she lectured and wrote. When Wright divorced her husband, she tragically lost custody of her daughter. She broke her hip in a fall and died prematurely after great suffering in Cincinnati. D. 1852.

"I am not going to question your opinions. I am not going to meddle with your belief. I am not going to dictate to you mine. All that I say is, examine, inquire. Look into the nature of things. Search out the grounds of your opinions, the for and the against. Know why you believe, understand what you believe, and possess a reason for the faith that is in you."

— Frances Wright, "Divisions of Knowledge" (1828)

Margaret Sanger

On this date in 1879, Margaret Louise Sanger (née Higgins), was born in Corning, N.Y., to a freethinking, Irish-born father and a Catholic Irish-American mother. Watching her mother die at age 48 of tuberculosis after bearing 11 children changed the course of Sanger’s life. As a child she was introduced to the power of the Catholic Church when the local priest locked the doors of the town hall to prevent agnostic Robert Ingersoll from speaking in Corning. She wrote in her autobiography of the spellbinding experience of hearing Ingersoll speak in the woods instead.

She would later repeatedly experience being locked out of public halls, even countries, under Catholic pressure. Her experience doing obstetrical nursing of the poor in New York City as a young mother herself galvanized her conviction that women had the right to control fertility. The turning point was witnessing the death of Sadie Sachs, 28, from a second illegal abortion. When Sachs had pleaded with her doctor for birth control, he had responded: “Tell Jake to sleep on the roof.”

Sanger researched contraception (coining the term birth control) while editing a monthly newspaper, The Woman Rebel (1914). Its primary purpose was to challenge the 1873 Comstock Act, which made it illegal to send “obscene, lewd or lascivious, immoral or indecent” publications through the mail, including articles about contraception and abortion, even if written by a physician.

Facing 45 years in prison when indicted under the law, Sanger fled the country, leaving behind a book, “Family Limitation.” It sold 10 million copies while Sanger continued research in England and the Netherlands. When she returned to the U.S. she was rearrested. After her daughter Peggy died of pneumonia in 1915, Sanger went on a headline-making speaking tour to challenge the charges, which were dropped in 1916.

That year she opened the first birth control clinic, which was raided. She spent the next two decades educating physicians about birth control and overseeing the creation of clinics across the U.S. In 1934 she brought the lawsuit that finally overturned much of the repressive Comstock Act. Over her lifetime she was jailed eight times, brought diaphragms to the U.S. and distributed them, helped develop contraceptive jelly, founded Planned Parenthood, and commissioned the creation of the birth control pill.

She was hailed as the “heroine” of history by H.G. Wells. She died at age 86 of congestive heart failure in Tucson, Ariz. (D. 1966)

"No Gods — No Masters."

— Motto of Sanger's newspaper The Woman Rebel

Rosemary Matson

On this date in 1917, feminist, activist, humanist and grassroots organizer Rosemary Matson was born at the family farm in Geneva, Iowa. Matson set an example for others by acting virtuously and advocating for world peace, equal opportunity and the right of women to have a voice. She lived in many places, including Chicago, Los Angeles, Boston, Berkeley, Calif., and, finally, in her longtime home in Carmel Valley, Calif.

Matson was a longtime member of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and the National Organization for Women. Through these organizations, she conducted outreach, served on committees and created programming. She also co-wrote a 100-page guide for a Unitarian Universalist (UU) course on patriarchy that used Unraveling the Gender Knot: Challenging the System that Binds Us by Allan G. Johnson as the text.

Matson did not identify as an atheist, and she and her husband Howard Matson became prominent figures in the UU’s Women and Religion Movement. However, she worked to remove sexist practices from Christianity and performed weddings and memorial services as a humanist minister, using nonsexist practices and nontheistic inspirational statements. She was honored with a UU Ministry to Women award in 1998 and received many other awards for her decades of leadership in peace and social justice movements.

She overcame breast cancer and was honored in the 2006 collection “Feminists Who Changed America, 1963-1975.” She died at age 97. (D. 2014)

"A new global ethic is absolutely essential at this critical juncture in history. But it can only come about with a more balanced social system — a balance between feminine and masculine characteristics, behaviors and perspectives."

— Rosemary Matson, "Women reborn — a humanistic revolution," essay in The Humanist

Etta Semple

On this date in 1855, Etta Semple (née Martha Etta Donaldson) was born into a Baptist family in Quincy, Illinois. After being left a widow with two sons in 1887, she married Matthew Semple of Ottawa, Kansas, and they had one son. Etta became Ottawa’s town radical, espousing freethought, feminism, opposing racial bigotry, capital punishment and “blue laws.”

Her pro-working class novels included Society and The Strike. She helped found the Kansas Freethought Association to “fight ignorance, superstition and tyranny” and in 1879 was elected its president. She also served as vice president of the American Secular Union. From her parlor she published the bimonthly Freethought Ideal, an eight-page newspaper with a 2,000 circulation. She amused Ottawans in the summer of 1901 by strolling arm in arm with Carry Nation, prompting a local wag to quip: “One believes in no saloons, and one believes in no god.”

In 1902 she opened a “Natural Cure” sanitarium with 31 rooms. “No tramp ever went away hungry, and no fallen woman has been kicked down by us,” she wrote. While the Ottawa Evening Herald hailed her as a “Good Samaritan” and “one of the greatest benefactors Ottawa has ever had,” she was stalked by an assassin. In an unsolved murder on March 28, 1905, an elderly patient in the hospital was bludgeoned in bed. Semple was believed by authorities to be the intended victim.

When she died of pneumonia at age 59, court was adjourned and crowds filled the cemetery for a godless oration in the spring sun. The Evening Herald’s banner headline read “Good Deeds of A Good Woman Are on the Tongues of Ottawa Today.” The story added: “It was the biggest funeral Ottawa had ever seen. It was also perhaps the most unusual. No minister spoke. No hymns were sung, no flowers decorated the parlor.” Mourners sang one of her favorite secular songs, “Scattering Seeds of Kindness,” which the newspaper called “emblematic of Mrs. Semple’s life.” (D. 1914)

"I never yet have seen the person who could withstand the doubt and unbelief that enter his mind when reading the Bible in a spirit of inquiry."

— Semple, "A Pious Congressman Twice Answered," The Truth Seeker (Feb. 23, 1895)

Eva Ingersoll

On this date in 1864, Eva Ingersoll (later Ingersoll-Brown) was the first of two daughters born to freethought great Robert G. Ingersoll and Eva Wakefield Ingersoll. Both Eva and her sister Maud shared the same middle name: Robert. The girls were gently tutored, and when the family moved to Washington, D.C., from Illinois, they received lessons in music, art, German, French and Italian, piano and singing. Ingersoll was a pleasing soprano and, like her father, enjoyed public performance and toyed with a concert career.

As a young woman she was described in a sexist manner by the St. Louis Globe-Democrat as “a most decided beauty, being of that fresh, dewy-eyed and virginal type that the English painters depict.” (March 31, 1881.) In 1889 she married Walston Hill Brown, a well-to-do builder of railroads and an agnostic like her. His wedding gift: a spacious estate known as Castle Walston on the Hudson River at Dobbs Ferry, New York. It was a measure of the family devotion that before the marriage, all parties arranged that the newlyweds would live with the Ingersolls six months and the Ingersolls would live with the Browns for six months.

Ingersoll, a feminist and suffragist, became a prominent humanitarian in New York, working with the Advisory Board of the New York Peace Society, the Women’s Trade Union League, the National Child Labor Committee, the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and the Society for the Advancement of the Colored People. She was president of the Child Welfare League. (D. 1928)

In 1911 Eva Ingersoll described the future woman who “will belong to no church, … will be fettered by no senseless formula or puerile dogma.”— "Rational Mothers and Infidel Gentlemen: Gender and American Atheism, 1865–1915" by Evelyn A. Kirkley (2000)

Victoria Woodhull

On this date in 1838, Victoria Woodhull was born in Ohio, the sixth of 10 children in an itinerant family. She and her sister Tennessee Claflin first became notorious as “clairvoyants” in a family money-making scheme. She married at 14 or 15 to an alcoholic and gave birth to the first of two children in her mid-teens, an experience that turned her into a challenger of the sexual double standard. Shaking off her marriage and her old life, she and her sister took on Wall Street. Known as “The Bewitching Brokers,” the sisters became the first women to open a bank, with the backing of admirer and railroad tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt.

At the national suffrage association in 1869, Victoria took feminists by storm with her impassioned argument that the 14th and 15th amendments already enfranchised women. She became the second woman in the nation, following Elizabeth Cady Stanton, to address the House Judiciary Committee. In 1872, Woodhull became the first woman to run for president, with Frederick Douglass as her vice president. The Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly, a lively, muckraking, feminist newspaper that she and her sister published for six years, specialized in iconoclasm, publishing the first English translation of Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto.