philosophers

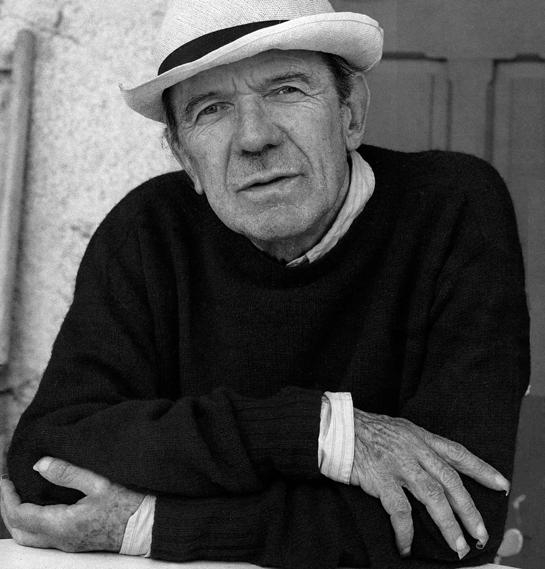

Michel Onfray

On this date in 1959, Michel Onfray was born in Argentan in northwest France. He taught philosophy in high school in Caen from 1983 to 2002. During this time he received his doctorate from the University of Caen in 1986. Onfray’s first book, Le ventre des philosophes, critique de la raison diététique (The Philosophers’ Stomach: A Critique of Dietary Reasoning) was published in 1989.

Onfray has written over 100 published books, which are popular throughout France as well as other parts of Europe, Latin America and even East Asia. However, only one, Traité d’Atheologie (2005) has been published in English: Atheist Manifesto: The Case Against Christianity, Judaism, and Islam.

In 2002 he founded the Université Populaire (People’s University) in Caen, at which he and others give free lectures on philosophy and other intellectual topics. The main thrust of Onfray’s work is atheist, materialist and hedonist. On the Brain@McGill website affiliated with the Institute of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addiction, Bruno Dubuc writes: “The French author Michel Onfray may be the philosopher who best represents the hedonist tradition today. In his many works, Onfray attempts to reposition the human body at the centre of our world view. … Onfray specializes in a certain ancient philosophy that has been buried under 2000 years of Christianity.”

In Atheist Manifesto, Onfray makes a strong case for removing all the remnants of Judeo-Christian ideology from our secular culture. Onfray is also a historian of philosophy who loves to point out why many philosophers are undeserving of our respect. He has so far published six volumes in the series La contre histoire de la philosophie (The Counter-History of Philosophy).

PHOTO of Onfray by Perline via CC 3.0,

“I persist in preferring philosophers to rabbis, priests, imams, ayatollahs, and mullahs. Rather than trust their theological hocus-pocus, I prefer to draw on alternatives to the dominant philosophical historiography: the laughers, materialists, radicals, cynics, hedonists, atheists, sensualists, voluptuaries. They know that there is only one world, and that promotion of an afterlife deprives us of the enjoyment and benefit of the only one there is. A genuinely deadly sin.”

— Onfray, "Atheist Manifesto" (2005)

Desmond M. Clarke

On this date in 1942, Desmond M. Clarke, a distinguished political philosopher and former Catholic priest, was born in Dublin, Ireland. After secondary schooling, Clarke joined the Capuchin Order and after novitiation attended University College Cork, completing a B.S. degree. Clarke earned a licentiate of theology from the University of Lyon followed by a bachelor of philosophy from the University of Leuven in Belgium. Later he earned a doctorate in philosophy from the University of Notre Dame, where he met his future wife Dolores Dooley, a former nun.

In 1974 he started teaching at University College Cork with his wife. They remained members of the university’s department of philosophy until retirement. Clarke published internationally recognized works on 17th-century philosophy, human rights theory and legal theory. In 1991 he was awarded a doctor of letters degree by the National University of Ireland. In 2014 he was awarded the gold medal by the Royal Irish Academy for his outstanding scholarly contribution to the humanities.

Unafraid to challenge authority with intellectual truth, Clarke was known as a courageous fighter for justice. Despite his Catholic roots, he was a fearless speaker against religious interference in Irish government. In his highly influential book Church and State: Essays in Political Philosophy (1984), Clark offered a powerful criticism of the Catholic Church’s stranglehold on Irish society, outlining how the autonomy of the individual citizen is one of the first victims in the oppression of the state by religious ideologies. It is a tribute to Clark’s bravery that he published this book at a time when few Irish academics were willing to address the controversial subject of religiosity in government. D. 2016.

“If one insisted that publicly funded schools should always reflect the beliefs of the majority, then the results would be obvious in a state where a voting majority is Marxist, Muslim, Mennonite or Calvinist. If that is unacceptable to Catholics, it cannot be avoided by inviting a state to decide which theology is ‘true,’ since states are incompetent to decide that question.”

— Clarke interview, The Irish Times, "Should the State fund religious schools?" (Jan. 27, 2015)

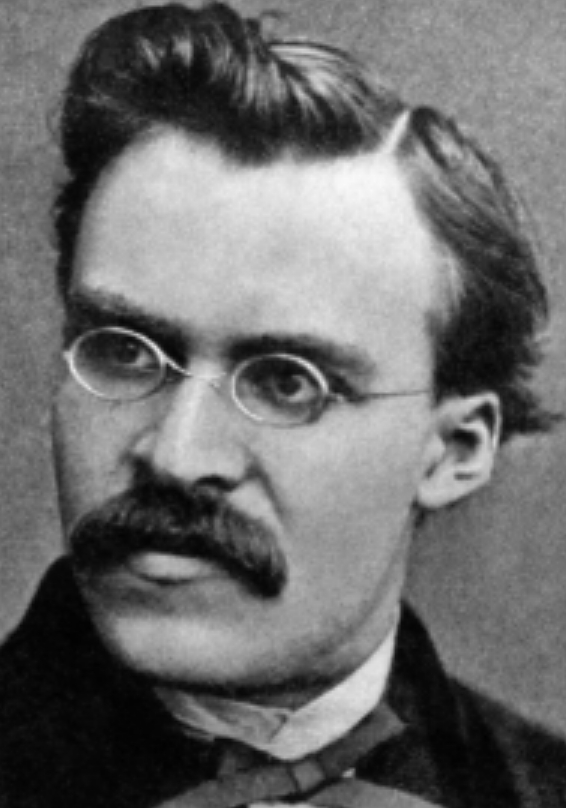

Gilles Deleuze

On this date in 1925, atheist philosopher and literary theorist Gilles Deleuze was born in Paris. A pioneer of post-structuralism, Deleuze is best known for two volumes of a work titled Capitalism and Schizophrenia, co-authored by psychoanalyst Félix Guattari. The first volume, Anti-Oedipus (1972), synthesizes the theories of Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud. The second volume, A Thousand Plateaus (1980), explores a much wider array of topics. Deleuze’s often impenetrable yet beautiful style has been attributed to the influence of Friedrich Nietzsche, who believed philosophy must be presented in conjunction with poetic language and vice versa.

Deleuze also took from Nietzsche a disdain for theology and the influence of religion over human morality. In Twilight of the Idols: or How to Philosophize with a Hammer (1889), Nietzsche lamented the “theologians who use the concept of ‘moral world order’ to keep infecting the innocence of becoming with ‘punishment’ and guilt.’ Christianity is a hangman’s metaphysics.”

Like many post-structural theorists, Deleuze found religions were “worth much less than the nobility and the courage of the atheisms they inspire.” (Two Regimes of Madness: Texts and Interviews, 1975-1995, 2007). Like the German philosopher Ernst Bloch, Deleuze posited that there is “always an atheism to be extracted from religion” and suggested that Christianity “secretes” atheism more than any other religion. (1991, What is Philosophy?)

Deleuze married Denise “Fanny” Grandjouan in 1956. He committed suicide in 1995 by jumping from his apartment window at age 70 after suffering from severe respiratory problems for years, including tuberculosis and removal of a lung.

“A concept is a brick. It can be used to build a courthouse of reason. Or it can be thrown through the window.”

— Deleuze, "A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia" (1980)

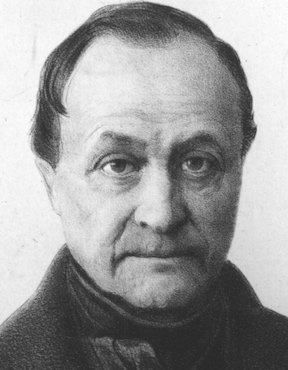

Auguste Comte

On this date in 1798, Auguste Comte, the founder of positivism and generally considered the father of sociology, was born in Montpellier, France. A mathematical prodigy, he rejected belief in God by age 14. He gave a series of lectures on positive philosophy in 1826, which were eventually published. Positivism is defined as a theory stating that certain (“positive”) knowledge is based on natural phenomena and their properties and relations. Thus, information derived from sensory experience, interpreted through reason and logic, is the source of much knowledge.

He married Caroline Massin in 1825. “The Course of Positive Philosophy” (“Cours de Philosophie Positive”) was a series of texts he wrote between 1830 and 1842. The works were translated into English by Harriet Martineau and abridged to form The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte, published in 1853. He was a close friend of John Stuart Mill.

In the 1840s he developed Religion de l’Humanité (Religion of Humanity) for positivists to fulfill the cohesive function once held by traditional worship. His ideas contributed to the rise of ethical culture societies and secular humanism. He died of stomach cancer in Paris at age 59. (D. 1857)

“Daily experience shows that the ordinary morality of religious men is not, at present, in spite of our intellectual anarchy, superior to that of the average of those who have quitted the churches. The chief practical tendency of religious conviction is … to inspire an instinctive and insurmountable hatred against all who have emancipated themselves, without any useful emulation having arisen from the conflict.”

— "The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte" (1853)

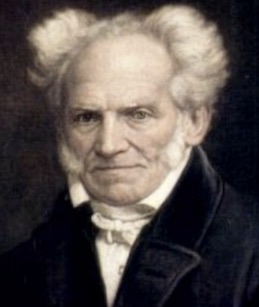

Arthur Schopenhauer (Quote)

“All religions promise a reward for excellences of the will or heart, but none for excellences of the head or understanding.”

— German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860), "The World as Will and Idea" (1819)

Ayn Rand

On this date in 1905, Ayn Rand (née Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum) was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, to a nonobservant Jewish family. She became an atheist as a teenager. Immigrating to the United States in 1921, she renamed herself Ayn (rhymes with “mine”) after a Finnish woman; the “Rand” was inspired by her Remington-Rand typewriter. She worked for Hollywood studios intermittently for 20 years, starting as an extra for Cecil B. DeMille and progressing to screenwriter. She married actor Frank O’Connor in 1929 in “a ‘proper’ nonreligious ceremony in a judge’s chambers.”

Rand’s first novel We the Living (1936) was not initially successful. The Fountainhead (1943) secured her place in literature, followed by Atlas Shrugged (1957). Rand’s novels promote her philosophy of Objectivism, promulgated in John Galt’s famous speech from Atlas Shrugged. Galt termed faith “a short-circuit destroying the mind.” Rand’s lecture “Faith and Force: the Destroyers of the Modern World” was delivered at Yale University in 1960.

During her lifetime, Rand’s writing provoked praise and condemnation, but more of the latter. In 2009, GQ critic Tom Carson described her books as “capitalism’s version of middlebrow religious novels” such as Ben-Hur and the “Left Behind” series. After undergoing surgery for lung cancer in 1974, she died of heart failure in 1982.

“The human race has only two unlimited capacities: one for suffering and one for lying. I want to fight religion as the root of all human lying and the only excuse for human suffering.”

— "Journals of Ayn Rand," ed. David Harriman (1997)

Michael Martin

On this date in 1932, renowned American philosopher and teacher Michael Martin was born in Cincinnati, Ohio. Martin was a respected academic promoter of atheism, penning several books examining the case against the existence of God.

Martin served with the U.S. Marine Corps in the Korean War before graduating from Arizona State University in 1956 with a degree in business administration. He earned a master’s degree in philosophy in 1958 from the University of Arizona and a Ph.D. in philosophy from Harvard University in 1962. That year, Martin began his teaching career at the University of Colorado as an assistant professor, joining the staff at Boston University in 1965, where he was a professor of philosophy until retiring.

The focal point of Martin’s research and writing was always the philosophy of religion and the defense of atheism. His best-known book was Atheism: A Philosophical Justification (1989), considered by some as one of the most analytical arguments against God’s existence. In its introduction he writes, “The aim of this book is not to make atheism a popular belief or even to overcome its invisibility. My object is not utopian. It is merely to provide good reasons for being an atheist. … My object is to show that atheism is a rational position and that belief in God is not. I am quite aware that atheistic beliefs are not always based on reason. My claim is that they should be.”

Martin wrote and edited several other books, including The Case Against Christianity (1991), Atheism, Morality, and Meaning (2002), The Impossibility of God (2003), The Improbability of God (2006) and The Cambridge Companion to Atheism (2006), along with numerous articles on atheism. He also engaged in a number of debates with Christian apologists. His philosophical interests extended to social science and law.

Martin was married to Jane Roland Martin, who spent much of her career as a philosophy professor at the University of Massachusetts-Boston focusing on education, gender and feminism. They married in 1962 and had two sons, Timothy and Thomas, and five grandchildren. (D. 2015)

“Since experiences of God are good grounds for the existence of God, are not experiences of the absence of God good grounds for the nonexistence of God?”

— Michael Martin, "Atheism: A Philosophical Justification" (1989)

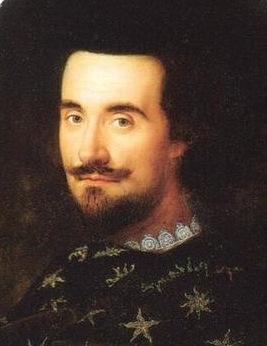

Giulio Cesare Vanini (Died)

On this date in 1619, Catholic friar Giulio Cesare Vanini (né Lucilio Vanini) was executed for heresy in Toulose, France. Born in 1585 in Italy, Vanini was educated in philosophy and theology at Rome University and entered the Carmelite order in 1603 as Fra Gabriele before studying canon and civil law in Padua. He traveled widely throughout Europe, espousing his rationalist viewpoints and supporting himself by giving lessons. He was also an early proponent of biological evolution among the first modern thinkers to view the universe as an entity governed by natural laws.

Vanini was driven from France in 1614. After taking refuge in England, he spent 49 days in the Tower of London. Returning to Italy, he was driven out of Genoa. Vanini went to southern France, where he published a book critical of atheism in 1615 in an attempt to clear himself from charges of heresy.

The following year his second book was published, which is credited with being closer to his real views, in which he advanced a naturalistic philosophy. The book was ordered burned by the Sorbonne, and Vanini was charged with atheism. He was arrested in 1618 and sentenced to have his tongue cut off, to be strangled at the stake and to have his body reduced to ashes. It is said he refused the ministrations of a priest. (D. 1619)

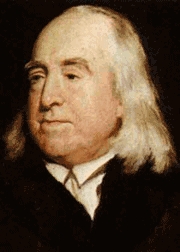

Jeremy Bentham

On this date in 1748, Jeremy Bentham was born in London. The great philosopher, utilitarian, humanitarian and atheist began learning Latin at age 4. He earned his B.A. from Oxford by age 15 or 16 and his M.A. at 18. His Rationale of Punishments and Rewards was published in 1775, followed by his groundbreaking utilitarian work Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Bentham propounded his principle of “the greatest happiness of the greatest number.” He worked for political, legal, prison and educational reform.

Inheriting a large fortune from his father in 1792, Bentham was free to spend his remaining life promoting progressive causes. The renowned humanitarian was made a citizen of France by the National Assembly in Paris. In published and unpublished treatises, Bentham extensively critiqued religion, the catechism, the use of religious oaths and the bible. Using the pen name Philip Beauchamp, he co-wrote a freethought treatise, Analysis of the Influence of Natural Religion on the Temporal Happiness of Mankind (1822). D. 1832.

“No power of government ought to be employed in the endeavor to establish any system or article of belief on the subject of religion.”

“[I]n no instance has a system in regard to religion been ever established, but for the purpose, as well as with the effect of its being made an instrument of intimidation, corruption, and delusion, for the support of depredation and oppression in the hands of governments.”

— Bentham, "Constitutional Code," "The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham," eds. F. Rosen and J. H. Burns (1983)

Giordano Bruno (Executed)

On this date in 1600, Giordano Bruno (né Filippo Bruno) was executed for heresy. The Italian philosopher was burned alive at the stake at age 52 for refusing to recant heretical ideas. Born in 1548, he entered the Dominican Order at Naples at age 15, adopting the name of Giordano. After being accused of heresy, he fled his Italian convent and traveled throughout Europe (1576-92). During two years in England, Bruno wrote and published six dialogues, including “On the Infinite, the Universe, and Worlds” and “The Ash Wednesday Supper.”

A Copernican, he rejected Aristotelian dogma and challenged entrenched religious teachings, declaring pantheist views. Some academics today regard him as a path-blazing intellectual, others as a victim of his nonconformity. When Bruno returned to Italy in 1592, he was arrested by the Inquisition. He was imprisoned for seven years in the dungeons of Rome, where he was tortured and isolated before being executed.

Bruno was just one of the more visible martyrs and victims of church persecution. Anonymous are the thousands of women put to death as “witches.” Known to us are such martyrs as Vanini, a monk burned as an atheist in 1619; Servetus, a Spanish physician executed under Calvin’s orders in 1553 for rejecting the trinity; Scottish student Thomas Aikenhead, hanged in 1697 for saying Christ was merely human; and those persecuted in the New World. Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson were banished for advocating religious tolerance. Quaker Mary Dyer was hanged in Boston in 1660 for heresy.

A statue to Bruno was erected at the site of his execution, Campo de’ Fiori near the Vatican, in 1889 by “Freethinkers of the World.” Biographer John Kessler wrote in “Giordano Bruno: The Forgotten Philosopher” (1900): “He is one martyr whose name should lead all the rest. He was not a mere religious sectarian who was caught up in the psychology of some mob hysteria. He was a sensitive, imaginative poet, fired with the enthusiasm of a larger vision of a larger universe.”

“Perchance you who pronounce my sentence are in greater fear than I who receive it.”

— Bruno's response to his judges upon conviction, quoted in "Giordano Bruno: His Life and Thought" by Dorothea Waley Singer (1950)

William Godwin

On this date in 1756, William Godwin was born in England, the son and grandson of strait-laced Calvinist ministers. Godwin followed in paternal footsteps, becoming a minister by age 22. His reading of atheist d’Holbach and others caused him to lose both his belief in the doctrine of eternal damnation and his ministerial position. Through further reading, Godwin gradually became godless. His Political Justice and The Enquirer (1793) argued for morality without religion and caused a scandal. He followed that philosophical book with a trail-blazing fictional detective story, Caleb Williams (1794).

He and Mary Wollstonecraft, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, secretly married in 1797. She died tragically after giving birth to their daughter Mary in 1797. Godwin and his second wife Mary Jane opened a bookshop for children and he became a proficient author of children’s books, employing a pseudonym due to his notoriety. Godwin’s life was marked by poverty and further domestic tragedies. He was responsible for a family of five children, none of whom had the same two parents.

Influenced by Coleridge, Godwin became more of a pantheist than an atheist. He died at age 80 and was buried next to Wollstonecraft in the graveyard of St. Pancras, the church where they had married in 1797. His second wife outlived him and eventually was also buried there, with the three of them sharing a headstone. (D. 1836)

“Either reason is the curse of our species, and human nature is to be regarded with horror; or it becomes us to employ our understanding and to act upon it, and to follow truth wherever it may lead us.”

— Godwin, "An Enquiry Into Political Justice, Vol. 1" (1793)

Sir Edward Herbert

On this date in 1583, Edward Herbert, “the father of English deism,” was born in County Shropshire. His father was the the sheriff of Montgomeryshire and a member of Parliament. Herbert studied at University College-Oxford from 1595 to 1600 (marrying his cousin Mary in 1599). In 1603 he was knighted by King James I. He was appointed ambassador to France in 1619 and received Irish peerage in 1624.

In 1629, Charles I raised him to the English peerage as Lord Herbert of Cherbury. Towards the end of his life, Herbert chose to side with Parliament during the English Civil War so that he could keep his library; he did not live to see the monarchy restored. Herbert left behind much diverse writing, including a light-hearted autobiography, a history of the reign of Henry VIII, a collection of verses and a collection of lute music he composed. His philosophical works, metaphysical or religious, included De veritate (On Truth) and Religio laici (Religion of the Laity).

Herbert is considered to be the father of English deism and a founder of the field of comparative religion. According to R.D. Bedford’s The Defence of Truth (1979), Herbert was strongly influenced by Continental deists, atheists and others of a rationalistic bent who were not widely read in England in the 17th century. He was interested in finding a rational form of religion instead of a revealed one. In his De religione gentium (Pagan Religions), published posthumously in 1663, he discussed what he saw as the five important propositions common to pre-Christian and modern religions:

“I. That there is one Supreme God. II. That he ought to be worshipped. III. That virtue and piety are the chief parts of divine worship. IV. That we ought to be sorry for our sins, and repent of them. V. That divine goodness doth dispense rewards and punishments both in this life and after it.” He died at age 65 in London. (D. 1648)

“There is a universal church made up of all people who assent to these basic beliefs, and [Herbert] rejects the Bible as revelation. ‘Revelation,’ he said, ‘is every divine and happy sentiment within.’ “

— Professor Jerram Barrs, lecture on Herbert and deism, Covenant Theological Seminary (Oct. 9, 2007)

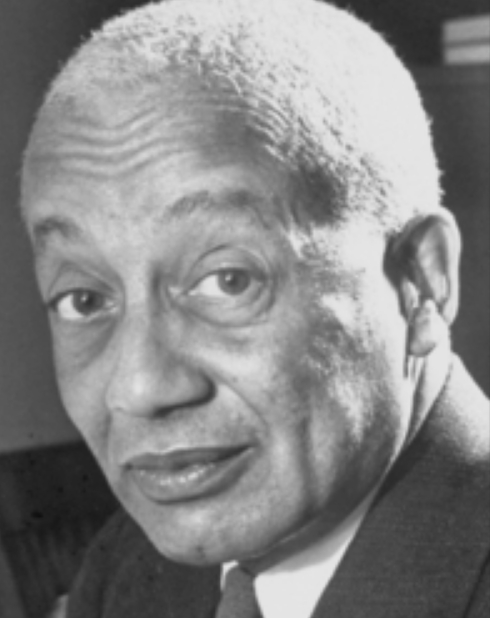

M.N. Roy

On this date (March 21), radical humanist and revolutionary Manabendra Nath Roy (né Narendra Nath Bhattacharya) was born in 1887 near Kolkata, India. The Bhattacharyas were Sakta Brahmins, a family of hereditary Hindu priests.

Roy majored in engineering and chemistry in college and became politically active due to the British partitioning of Bengal in 1905. A failed attempt during World War I to obtain German support for an Indian uprising against imperial rule made Roy a global wanderer, eventually landing him in Mexico via China, Korea, Japan and the U.S.

He became involved in the Mexican Revolution and became part of the international communist movement. Fleeing to the Soviet Union, he barely escaped Stalin’s wrath, only to have British authorities subject him to a harsh five years in prison on his return to India. During World War II, he urged full military support for Great Britain, thinking that the defeat of fascism was of higher priority than Indian independence.

In extensive writings that developed his philosophy of radical humanism, Roy tried to disassociate philosophy from religion and instead combine it with science. He helped create the International Humanist and Ethical Union (now Humanists International) and became one of its first vice presidents in absentia after the accident mentioned below prevented him from attending the inaugural convention in Amsterdam in 1952.

Roy established the Indian Renaissance Institute in the Himalayan foothill city of Dehradun, where the Radical Humanist, a journal he founded, is still published as of this writing in 2024. The movement has had a profound impact on secular thought in India and internationally.

Hermann Bondi, a stalwart of the British Humanist Association, cited Roy as an example of profound intellectual evolution. Acclaimed German-American psychoanalyst and philosopher Erich Fromm, a humanist himself, lauded Roy’s “Reason, Romanticism and Revolution” as a “thorough and brilliant analysis.”

He died of a heart attack at age 66 after undergoing two attacks of cerebral thrombosis sustained falling down a hill in 1952, causing partial paralysis. (D. 1954)

“The realization of the possibility of a secular rational morality opens up a new perspective before the modern world. … It must be realized that human existence is self-contained and self-sufficient; and that, therefore, man can find in himself the power to work out his destiny, to make a better world to live in.”

— M.N. Roy, "Reason, Romanticism and Revolution" (1952)

Erich Fromm

On this date in 1900, psychoanalyst and humanist philosopher Erich Fromm was born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Grandfathers on both sides of the family were Orthodox rabbis. He earned his Ph.D. in sociology in 1922 from the University of Heidelberg and trained at the Psychological Institute in Berlin. By 1926 he had rejected Orthodox Judaism. Fromm took the story of Adam and Eve and turned it into an allegory in praise of the quest for knowledge, the questioning of authority and the use of reason.

He moved in 1930 to Geneva to escape Nazism, then emigrated to the U.S. in 1934. Fromm taught at Columbia University and became a citizen in 1940. His pinnacle work, Escape from Freedom, was published in 1941, followed by Man for Himself: An Inquiry into the Psychology of Ethics (1947).

Fromm moved to Mexico in 1950 to become a professor at the National Autonomous University, where he taught until 1965. The Art of Loving (1956) became an international best-seller. That was followed by The Sane Society (1955), You Shall Be as Gods (1966), The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness (1973), and To Have or to Be (1976). He started teaching in the U.S. again in the late 1950s at Michigan State University and later New York University.

He was a co-founder of several institutes, including the William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis and Psychology. As a critic of McCarthyism and the Vietnam War, he helped found the international peace group SANE.

In The Sane Society, Fromm distinguishes “intelligence” (“thought in the service of biological survival”) from “reason,” which “aims at understanding.” “In observing the quality of thinking in alienated man, it is striking to see how his intelligence has developed and how reason has deteriorated.” Fromm called ethics “inseparable from reason.”

Fromm “just didn’t want to participate in any division of the human race, whether religious or political,” wrote Keay Davidson in “Fromm, Erich Pinchas” ( American National Biography Online, Feb. 2000) and was a confirmed atheist. He moved to Switzerland in 1974, where he died just before his 80th birthday in 1980.

“If faith cannot be reconciled with rational thinking, it has to be eliminated as an anachronistic remnant of earlier stages of culture and replaced by science dealing with facts and theories which are intelligible and can be validated.”

— Fromm, "Man for Himself" (1947)

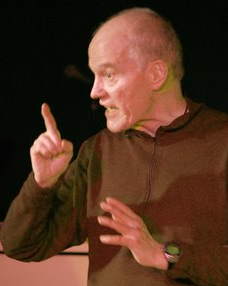

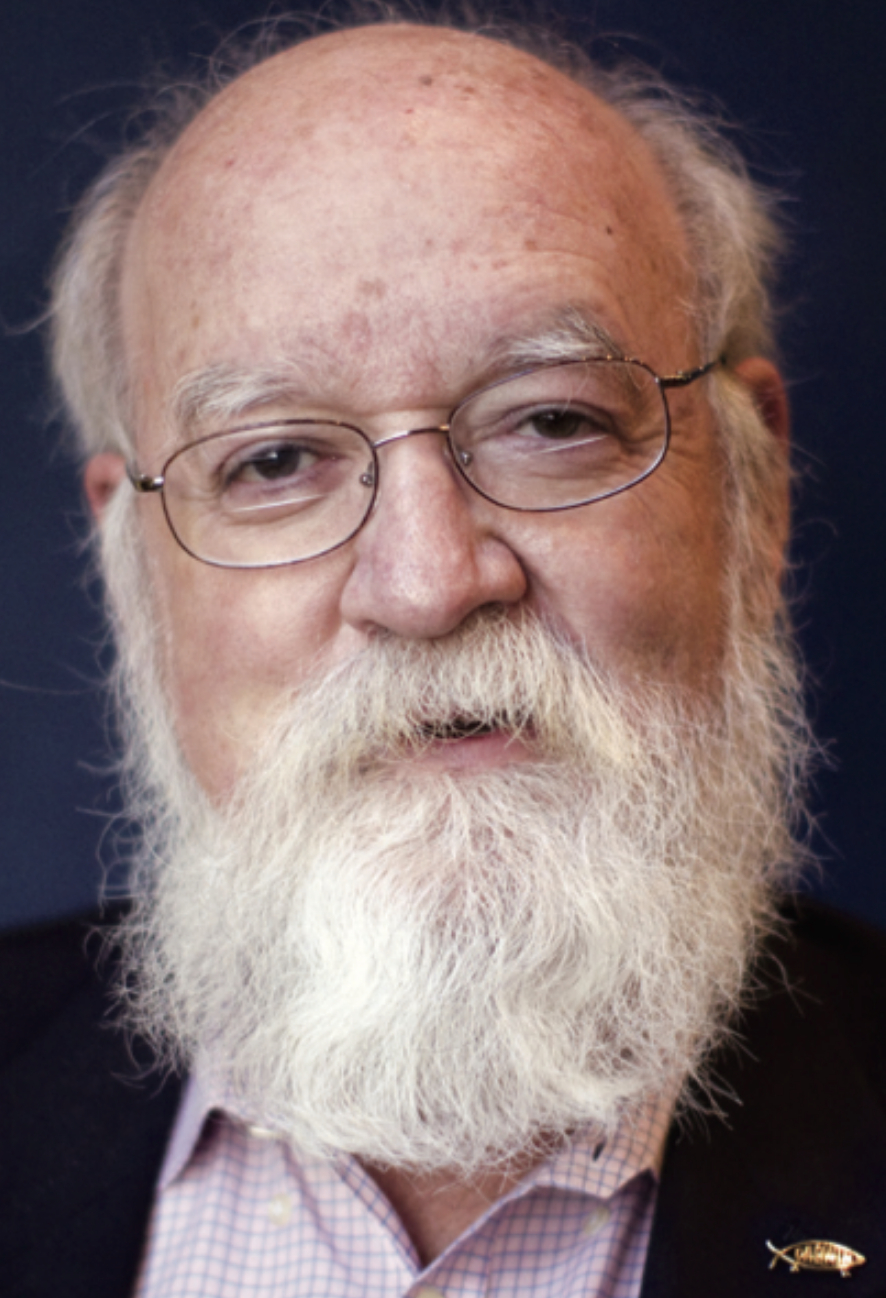

Daniel C. Dennett

On this date in 1942, philosopher Daniel Clement Dennett III was born in Boston, the son of Ruth Marjorie (née Leck) and Daniel Clement Dennett Jr. He earned his B.A. in philosophy at Harvard in 1963 and his doctorate in philosophy from Oxford in 1965. Since 1971, he taught at Tufts University with the exception of visiting professorships and was Austin B. Fletcher Professor of Philosophy there. His specialty was consciousness.

His 1992 book Consciousness Explained was widely credited with advancing the understanding of how various parallel brain processes contribute to consciousness. He also wrote often about the philosophy of the mind and of science and was considered a leading proponent of “neural Darwinism.”

Among his many books are Darwin’s Dangerous Idea (1995), Freedom Evolves (2003), Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon (2006), Kinds of Minds: Towards an Understanding of Consciousness (1997), Science and Religion (2010), Caught in the Pulpit: Leaving Belief Behind (with Linda LaScola, 2013) and From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds (2017).

His well-known 2003 New York Times piece endorsing the use of the term “Bright” to describe the nonreligious began: “The time has come for us brights to come out of the closet. What is a bright? A bright is a person with a naturalist as opposed to a supernaturalist world view. We brights don’t believe in ghosts or elves or the Easter Bunny — or God. We disagree about many things, and hold a variety of views about morality, politics and the meaning of life, but we share a disbelief in black magic — and life after death.”

His scholarship earned Dennett a place among the “Four Horsemen” of literary atheism, along with Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris and the late Christopher Hitchens. Dennett received FFRF’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award in 2008 and in his acceptance speech urged atheists to “come out of the closet.” He was a co-founder of the Clergy Project in 2011 and was an FFRF honorary officer.

He and Susan Bell married in 1962 and lived in North Andover, Mass. They had a son, Peter, and a daughter, Andrea. He died at age 82 at the Maine Medical Center in Portland of complications from interstitial lung disease. (D. 2024)

“Politicians don’t think they even have to pay us lip service, and leaders who wouldn’t be caught dead making religious or ethnic slurs don’t hesitate to disparage the ‘godless’ among us.”

“From the White House down, bright-bashing is seen as a low-risk vote-getter. And, of course, the assault isn’t only rhetorical: the Bush administration has advocated changes in government rules and policies to increase the role of religious organizations in daily life, a serious subversion of the Constitution. It is time to halt this erosion and to take a stand: the United States is not a religious state, it is a secular state that tolerates all religions and — yes — all manner of nonreligious ethical beliefs as well.”

— Dennett, "The Bright Stuff," New York Times (July 12, 2003); photo by Brent Nicastro

Ludwig Buchner

On this date in 1824, German physician and philosopher Friedrich Karl Christian Ludwig Buchner was born in Darmstadt, Germany. His father was a physician. Two of his five siblings, writer and playwright Georg and literary historian Alexander, were also freethinkers. His other siblings were Mathilde, the novelist Louise and Wilhelm, a factory owner and parliamentarian. He was educated at the Universities of Giessen, Strassburg, Wurzburg and Vienna. After earning his medical doctorate with honors from Gissen in 1848, he taught medicine at Tubingen University. In 1855 he published his most famous work, Kraft und Stoff (Force and Matter).

This book, because of its scientific, atheistic and rationalist ideas, caused his dismissal at Tubingen, and thus he began practicing medicine in Darmstadt. Force and Matter “made a bold attempt at transforming the then prevailing theory of the world which was based on theological philosophy, and adapting it to the requirements of modern science.” (Preface to Force and Matter, 1855.)

Buchner wrote numerous articles and books, including Nature and Spirit, The Soul of Animals, Man’s Place in Nature, The Idea of God, Darwinism and Socialism and The Influence of Heredity. Considered one of the fathers of scientific materialism in Germany, he traveled and lectured widely, including in the U.S. An obituary in the journal Science by the American Association for the Advancement of Science said: “Buchner was well known for his series of popular works on physical science and the theory of evolution, as well as for numerous contributions to physiology, pathology and other sciences.” (Vol. 9, January-June 1899.)

“[Buchner’s] philosophic and scientific writings entitle him to a foremost place in the gallery of great men who have led the human race out of the bondhouse of superstition to the promised land of reason.” (George Seibel in “Thomas Paine in Germany,” from The Open Court, Vol. 34, January 1920.) (D. 1899)

“If God is in us all and is the soul of the world, then he must directly partake of all our wickedness and imperfections. … In one man he does good, while in another he works evil and contends against his own laws. … But enough of all this nonsense!”

— Buchner, "Force and Matter" (1855)

A.C. Grayling

On this date in 1949, British author, philosopher and atheist Anthony Clifford Grayling was born in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), where his father was a banker. He spent his childhood in Africa. When he was 19, his older sister Jennifer was murdered in Johannesburg. When her parents went to identify the body, her mother had a fatal heart attack. After earning a B.A., M.A. and Ph.D. in England, Grayling lectured in philosophy at Bedford College-London and St. Anne’s College-Oxford before taking up a post in 1991 at Birkbeck College-University of London, where he was a philosophy professor until 2011. He then founded and became the first master of New College of the Humanities.

Grayling is the author of over 30 books on philosophy, biography, the history of ideas, human rights and ethics, including The Refutation of Scepticism (1985), The Future of Moral Values (1997), Wittgenstein (1992), What Is Good? (2000), The Meaning of Things (2001), The Good Book (2011), The God Argument (2013), The Age of Genius: The Seventeenth Century and the Birth of the Modern Mind (2016), War: An Enquiry (2017) and Democracy and its Crises (2017). His 2006 play “Grace” was co-written with Mick Gordon. The title character is a science professor who rejects religion.

He’s a vice president of the British Humanist Association, an honorary associate of the National Secular Society and has held positions with many other academic and literary organizations. The awards bestowed on him are numerous, including the Order of the British Empire, and others honoring his contributions to philosophy and ethics. One current biographical source says that Grayling believes that religion for historical reasons has had influence far out of proportion to the number of adherents and its intrinsic merits, “with the result that they can distort such matters as public policy (e.g., on abortion) and science research and education (e.g., stem cells, teaching of evolution).”

In a 2013 interview, freethinker Sam Harris asked Grayling if “a person can be both a humanist and a person of faith?” Grayling replied, “No, religion and humanism are not consistent — unless you mean ‘humanism’ in the Renaissance sense, where it denoted the study of classical literature. But this study soon showed people that the ideas and outlook of classical thought is at odds with religion, which is why humanism is now a secular philosophy.”

He and his wife, novelist Katie Hickman, have a daughter, Madeleine, and a stepson, Luke. He also has a son, Jolyon, and a daughter, Georgina, from his first marriage.

“In the study of history I became aware of the effects of religious divisions and sectarianism on individuals and societies, and came to think that freedom from religious influence is a human rights issue. I am an atheist, a secularist and a humanist.”

— Grayling, interviewed by Sam Harris, samharris.org (March 30, 2013)

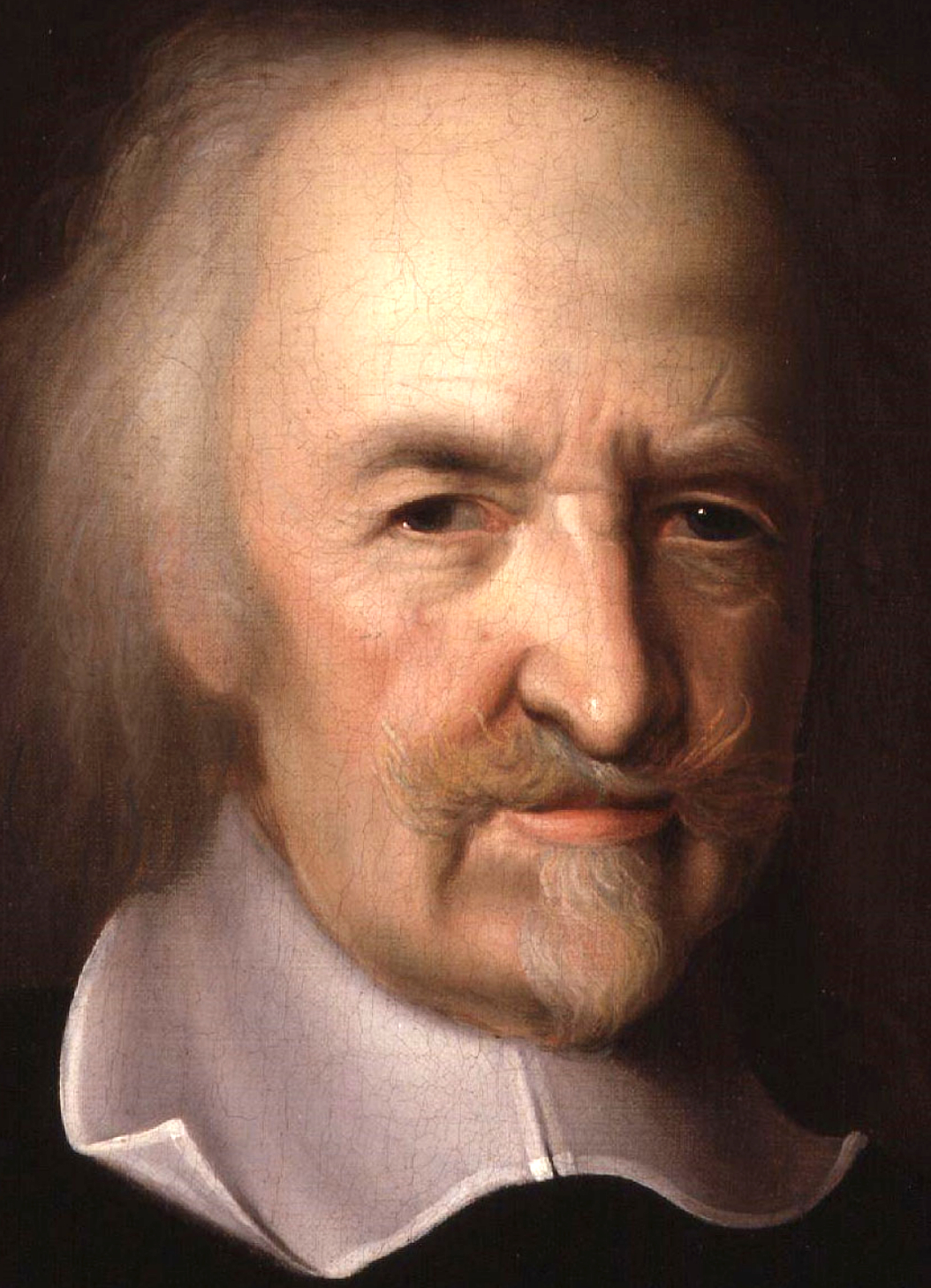

Thomas Hobbes

On this date in 1588, Thomas Hobbes was born prematurely on “Good Friday” in England, his birth precipitated by his mother’s fear of the invasion of the Spanish Armada. Thomas was the precocious son of a ne’er-do-well parson. As a tutor, Hobbes made the “Grand Tour” of Europe three times, once meeting Galileo. Contemporary John Aubrey described Hobbes as “contemplative,” and charitable, always carrying a pen and ink horn in his cane, with a notebook handy so he could jot down ideas during daily constitutionals. Aubrey noted that Hobbes once wrote a poem in Latin hexameter and pentameter “on the encroachments of the clergy on the civil power,” which contained over 500 verses.

Hobbes’ De Cive was published in 1642 and Leviathan in 1651, in which Hobbes proposed the idea that a “social contract” was necessary for civil peace. Its analysis of religion brought charges of atheism, then punishable by death. When things got too hot in England after Leviathan, Hobbes repaired to Paris. After the Great Plague in 1665 was followed by the Great Fire the next year, religionists sought a scapegoat. Parliament once more targeted Leviathan for being heresy. Hobbes hastily burned many of his papers.

His writing helped give birth to the Enlightenment, by analyzing and questioning religious assumptions, and proposing that religion was created by humans. Hobbes attributed “opinion of ghosts, ignorance of second causes, devotion towards what men fear, and taking of things casual for prognostics, consisteth the natural seed of religion; which, by reason of the different fancies, judgements, and passions of several men, hath grown up into ceremonies so different that those which are used by one man are for the most part ridiculous to the other.”

Whether deist or covert atheist, Hobbes was anti-clerical, anti-Puritan and anti-Catholic and managed to live out his full 91 years in perilous times due to influential friends. (D. 1679)

“Seeing there are no signs nor fruit of religion but in man only, there is no cause to doubt but that the seed of religion is also only in man.”

“Fear of power invisible, feigned by the mind or imagined from tales publicly allowed, RELIGION; not allowed, SUPERSTITION.”

— Sir Thomas Hobbes, "Leviathan" (1651)

Sam Harris

On this date in 1967, author and neuroscientist Samuel Benjamin Harris, a key figure in the 21st century freethought movement, was born in Los Angeles, the son of TV producer and writer Susan (Spivak) Harris and actor Berkeley Harris, who divorced when Sam was 2. He grew up in his mother’s secular household and enrolled at Stanford University to study philosophy but left during his sophomore year to study Eastern religions and meditation in India. He eventually returned to Stanford and graduated in 2000.

He started writing his first book, The End of Faith, after the Sept. 11 attacks in 2001. It received the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for First Nonfiction in 2005 and was followed by his Letter to a Christian Nation in 2006. Harris married in 2004 and has two daughters with his wife Annaka, an author and science editor. They co-founded the nonprofit Project Reason in 2007. He received a Ph.D. in cognitive neuroscience in 2009 from UCLA. Five of his books are New York Times bestsellers. His latest, as of this writing, are Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion (2014) and Islam and the Future of Tolerance (with British activist Maajid Nawaz, 2015).

Harris is generally considered a member of the “Four Horsemen of New Atheism” along with Richard Dawkins and the late Daniel Dennett and Christopher Hitchens. The name comes from the title of a video they made during a two-hour unmoderated discussion at Hitchens’ home on Sept. 30, 2007. Journalist Simon Hooper described New Atheism as “the view that superstition, religion and irrationalism should not simply be tolerated but should be countered, criticized and exposed by rational argument wherever its influence arises in government, education and politics.”

Harris has no use for the term New Atheism or for the atheist label. In a 2007 speech he said that while he had become “one of the public voices of atheism, I never thought of myself as an atheist before being inducted to speak as one. I didn’t even use the term in The End of Faith, which remains my most substantial criticism of religion. And, as I argued briefly in Letter to a Christian Nation, I think that ‘atheist’ is a term that we do not need, in the same way that we don’t need a word for someone who rejects astrology. We simply do not call people ‘non-astrologers.’ All we need are words like ‘reason’ and ‘evidence’ and ‘common sense’ and ‘bullshit’ to put astrologers in their place, and so it could be with religion.”

PHOTO: By Christopher Michel under CC 4.0.

“It is time that we admitted that faith is nothing more than the license religious people give one another to keep believing when reasons fail.”

— Harris in "Letter to a Christian Nation" (Knopf, 2006)

Joseph Fletcher

On this date in 1905, Joseph Francis Fletcher III was born in Newark, N.J. He received a B.A. from West Virginia University before going on to receive a bachelor of divinity from Berkeley Divinity School in 1929 and a doctor of sacred theology from the University of London in 1932. He was ordained an Episcopal priest, but later renounced his belief in God and identified as a humanist.

Fletcher was a philosopher and a theologian whose work in the field of biomedical ethics was pioneering. Even when he was religious, his ethics were humanist, based on human suffering and consequences rather than biblical rules. He was an advocate for family planning, abortion, euthanasia and the sterilization of unfit parents.

He taught Christian ethics and pastoral theology at the Episcopal Theological School from 1944 to 1970, and medical ethics at the University of Virginia at Charlottesville from 1970 to 1977. He wrote several books, including Morals and Medicine (1954), Situation Ethics (1966), and Humanhood: Essays in Biomedical Ethics (1979). He was also a founding member of Planned Parenthood, the Association for Voluntary Sterilization, Society for the Right to Die and the Soviet-American Friendship Society.

In an autobiographical essay published posthumously in Memoir of an Ex-Radical, Fletcher describes his loss of faith at age 65, which he says was at first prompted by a realization that the church would never be a significant advocate in the social justice movement. He wrote: “[This realization] forced me to take a hard look at Christian doctrine itself, on its own merits: God, Jesus, revelation, sin, salvation — the whole repertory. Looking at it like that, I said to myself what I no doubt often glimpsed along the way, that the whole thing was weird and untenable.”

After this experience, Fletcher did not immediately resign from his position at the Episcopal Theology School. He called himself “an alienated or unbelieving theologian.” (D. 1991)

“[W]ith an absolute God, his word revealed and his will eternal, how could relativity in ethics get anywhere with them?”

— Fletcher explaining the outraged response from Christians, Muslims and Jews to his idea of situational ethics, ("Memoir of an Ex-Radical," 1993)

David Chalmers

On this date in 1966, philosopher David John Chalmers was born in Sydney, Australia. Chalmers earned a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and computer science from the University of Adelaide in 1986. He was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University before transferring to Indiana University at Bloomington, where he obtained a Ph.D. in 1993 in philosophy and cognitive science.

He worked at Washington University in St. Louis from 1993-95 and at the University of California-Santa Cruz from 1995-98. He worked in the Department of Philosophy and the Center for Consciousness Studies at the University of Arizona from 1999 to 2004. Chalmers accepted a part-time professorship at New York University in 2009 and then a full-time professorship at the same university in 2014.

His 1996 book The Conscious Mind is considered a seminal work on consciousness. His numerous papers and books have had great influence in the realms of cognitive science, philosophy of the mind and philosophy of language. In 2013 he was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences. He lives in New York with his partner Claudia Passos Ferreira, a philosopher and psychologist from Rio de Janeiro who teaches at the NYU Center for Bioethics.

Photo by zereshk under CC 3.0.

“Now I have to say I’m a complete atheist. I have no religious views myself and no spiritual views, except very watered down humanistic spiritual views. And consciousness is just a fact of life. It’s a natural fact of life.”

— Chalmers, interview on “Encounter” on Australian ABC National Radio (April 10, 2011)

David Hume

On this date in 1711, David Hume was born in Edinburgh, Scotland. The influential empiricist philosopher was raised by his widowed mother, a strict Calvinist. He entered the University of Edinburgh at age 11 and studied there for three years, after which he was self-educated.

His first philosophical book, A Treatise of Human Nature (1739-40), was guardedly skeptical (making references to “monkish virtues”). Critics used the book to deny Hume a teaching position at the University of Edinburgh and later at Glasgow University. Through this controversy, Hume humorously wrote a friend that he was “a sober, discreet, virtuous, frugal, regular, quiet, good-natured man, of a bad character.” (Cited in 2000 Years of Disbelief by James A. Haught.) Hume was finally granted a relatively congenial position as librarian at Edinburgh University in 1752.

In Essays, Moral, Political and Literary (1741), Hume dismissed priests as “the pretenders to power and dominion, and to a superior sanctity of character, distinct from virtue and good morals.” In An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748), he famously asserted that “a miracle can never be proved, so as to be the foundation of a system of religion.” Hume defined a miracle as “a violation of the laws of nature.”

His other books include The Natural History of Religion, which Hume, who was dying of cancer, arranged to be published posthumously. In The Natural History of Religion, Hume wrote: “Examine the religious principles which have, in fact, prevailed in the world, and you will scarcely be persuaded that they are anything but sick men’s dreams.” In the same work, Hume called the god of the Calvinists “a most cruel, unjust, partial and fantastical being.”

Hume also wrote The History of England (six volumes, 1754-61). The charitable and cheerful Hume was well-respected by fellow Britons, clergy excepted, and was on friendly terms with Adam Smith and Edward Gibbon. (D. 1776)

“The Christian religion not only was at first attended with miracles, but even at this day cannot be believed by any reasonable person without one.”

— Hume, "An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding" (1748)

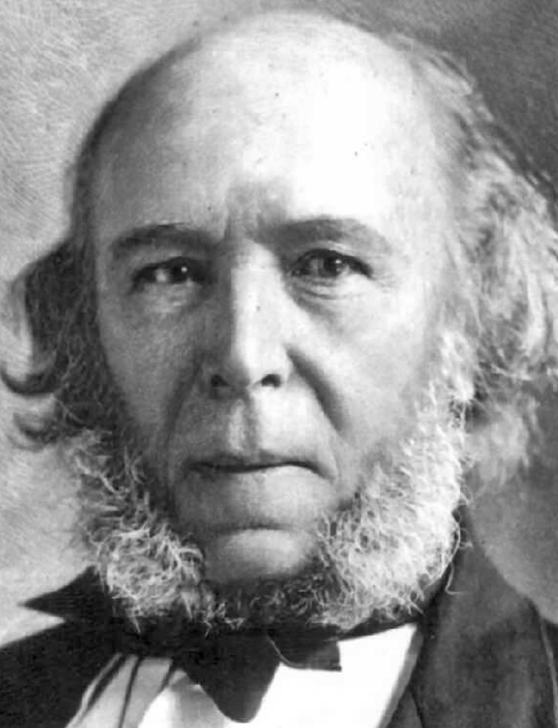

Herbert Spencer

On this date in 1820, Herbert Spencer was born in England. The agnostic philosopher was educated in engineering but worked as a journalist and writer. Spencer became good friends with leading thinkers and writers, such as Thomas Huxley and novelist George Eliot. His Principles of Psychology was published in 1855, followed by a series of major works on the principles of biology, sociology, education and ethics.

Spencer, in Social Statics (1850), wrote: “Whatever fosters militarism makes for barbarism; whatever fosters peace makes for civilization.” (D. 1903)

“Religion has been compelled by science to give up one after another of its dogmas, of those assumed cognitions which it could not substantiate.”

— Spencer, "First Principles" (1862)

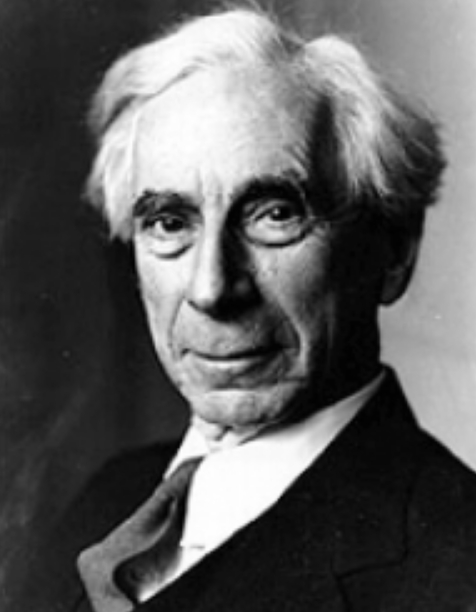

Bertrand Russell

On this date in 1872, Bertrand Arthur William Russell was born in England. “A good world needs knowledge, kindliness, and courage; it does not need a regretful hankering after the past, or a fettering of the free intelligence by the words uttered long ago by ignorant men,” Russell wrote. “Bertie” to friends, Russell, during his 97 years, did all he could to add to human knowledge and to inspire kindness.

His second wife, Dora Black, called him “enchantingly ugly.” An attorney who won a suit to void Russell’s appointment to the philosophy department at the College of the City of New York in 1940 because of his liberal views, described Russell as “lecherous, libidinous, lustful, venerous, erotomaniac, aphrodisiac, irreverent, narrow-minded, untruthful and bereft of moral fiber.”

“What I wish at bottom is to become a saint,” Russell once admitted, but he couldn’t help being pleased by the label “aphrodisiac.” The mathematician (who called his first encounter with Euclid “as dazzling as first love”) philosopher and social activist published 75 books.

He launched headlong into a life of radicalism in his 40s as a pacifist opposing World War I. He liked to recount his experience in prison, where he was sentenced for his pacifism, and in his autobiography wrote: “I was much cheered on my arrival by the warden at the gate, who had to take particulars about me. He asked my religion, and I replied ‘agnostic.’ He asked how to spell it, and remarked with a sigh, ‘Well, there are many religions, but I suppose they all worship the same God.’ This remark kept me cheerful for about a week.”

He spent his last years courageously working for nuclear disarmament. In “The Faith of a Rationalist,” broadcast by the BBC in 1953, Russell observed: “Cruel men believe in a cruel God and use their belief to excuse their cruelty. Only kindly men believe in a kindly God, and they would be kindly in any case.” One of his maxims was “Never try to discourage thinking, for you are sure to succeed.” Russell won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950 “in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought.” (D. 1970)

“I believe that when I die I shall rot, and nothing of my ego will survive. I am not young, and I love life. But I should scorn to shiver with terror at the thought of annihilation. Happiness is nonetheless true happiness because it must come to an end, nor do thought and love lose their value because they are not everlasting.”— Russell, "What I Believe" (1925), reprinted in "Why I Am Not a Christian" (1957)

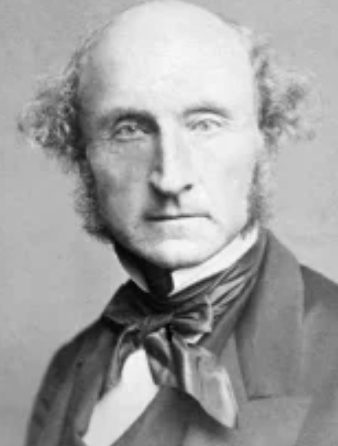

John Stuart Mill

On this date in 1806, John Stuart Mill was born in England. Mill, who met Jeremy Bentham as a young man, became a champion of individual liberty. With Bentham, Mill advanced utilitarianism, a philosophy advocating that the role of government is to create the greatest amount of good with the least evil. Mill, known for his clear writing style and compelling logic, advanced and popularized such ideals as social and sexual equality, the public ownership of national resources, and political liberty.

Mill was tutored at a tender age by his father, James Mill, who was an agnostic. Mill could not remember a time when he could not read Greek, writing in his autobiography that he started Greek study by age 3.

Mill wrote in his Autobiography (1873) that his father “impressed upon me from the first, that the manner in which the world came into existence was a subject on which nothing was known: that the question, ‘Who made me?’ cannot be answered, because we have no experience or authentic information from which to answer it; and that any answer only throws the difficulty a step further back, since the question immediately presents itself, ‘Who made God?’ “

Even as a teen, Mill wrote a defense of skeptic Richard Carlile, jailed for six years for “blasphemous libel.” After a clerkship in India House (headquarters of the East India Company), Mill became part of the “philosophic Radicals,” and wrote for a number of journals. A System of Logic, in two volumes, came out in 1843, followed by Principles of Political Economy (1848), On Liberty (1859), Utilitarianism (1863) and The Subjection of Women (1869). The latter book was influenced by his wife Harriet Hardy Taylor, a longtime friend whom Mill married in 1851.

In On Liberty, a work dedicated to his wife, who died in 1858, Mill rejected a standard of ethics predicated on obedience, or the crushing of individuality, whether by “enforcing the will of God or the injunctions of men.” Mill termed Christianity “essentially a doctrine of passive obedience; it inculcates submission to all authorities found established.” Mill was a member of Parliament from 1865-68, rising to the defense of Charles Bradlaugh, the atheist politician who had to fight for years to be seated in Parliament.

Although Mill’s views were unpopular, Gladstone once referred to Mill as “the saint of Rationalism.” Mill’s Reform Bill of 1867, the first attempt to grant the vote to British women, while unsuccessful, ignited the British suffrage movement.

Three essays on religion were published posthumously. In them, Mill hints that he had adopted a deistic belief in what he termed a “limited liability god,” surprising his freethinking friends. Mill wrote in Utility of Religion, published in 1874, that belief “in the supernatural … cannot be considered to be any longer required.” He wrote in his Autobiography (1873): “The world would be astonished if it knew how great a proportion of its brightest ornaments — of those most distinguished even in popular estimation for wisdom and virtue — are complete skeptics in religion.” (D. 1873)

“A large proportion of the noblest and most valuable teaching has been the work, not only of men who did not know, but of men who knew and rejected the Christian faith.”

— Mill, "On Liberty" (1859)

Jean-Paul Sartre

On this date in 1905, Jean-Paul Sartre was born in Paris, an only child and the great-nephew of humanitarian Albert Schweitzer. He and his lifelong companion Simone de Beauvoir met at the Ecole Normale Superieure, where he graduated in 1929. After teaching and traveling for several years, Sartre headed a clique of Left Bank intellectuals. His first novel, La Nausee, came out in 1938, followed by the fictional Le Mur (1939), then a collection of short stories and several plays. Drafted during World War II, Sartre was imprisoned for a year in Germany and either escaped or was released, returning to work in the Resistance.

After the war he founded the magazine Le Temps Modernes. Being and Nothingness was his existential masterpiece (1943). Sartre’s nonfiction also included Existentialism and Humanism (1946) and What Is Literature (1947). Sartre was twice the target of terrorist attacks by opponents of Algerian independence, who exploded bombs in his apartment in the early 1960s. He headed the International War Crimes Tribunal set up by Bertrand Russell to judge American conduct in Indochina. His last work was an unfinished biography of Gustave Flaubert.

Atheism was an essential ingredient in Sartre’s existentialism: “Illusion has been smashed to bits; martyrdom, salvation and immortality are falling to pieces; the edifice is going to rack and ruin; I collared the Holy Ghost in the basement and threw him out.” (The Words, 1964).

A heavy smoker, he died at age 68 in Paris of pulmonary edema. (D. 1980)

PHOTO: Sartre in Beijing in 1955.

“We have lost religion, but we have gained humanism.”

— Jean-Paul Sartre, Life magazine (Nov. 6, 1964)

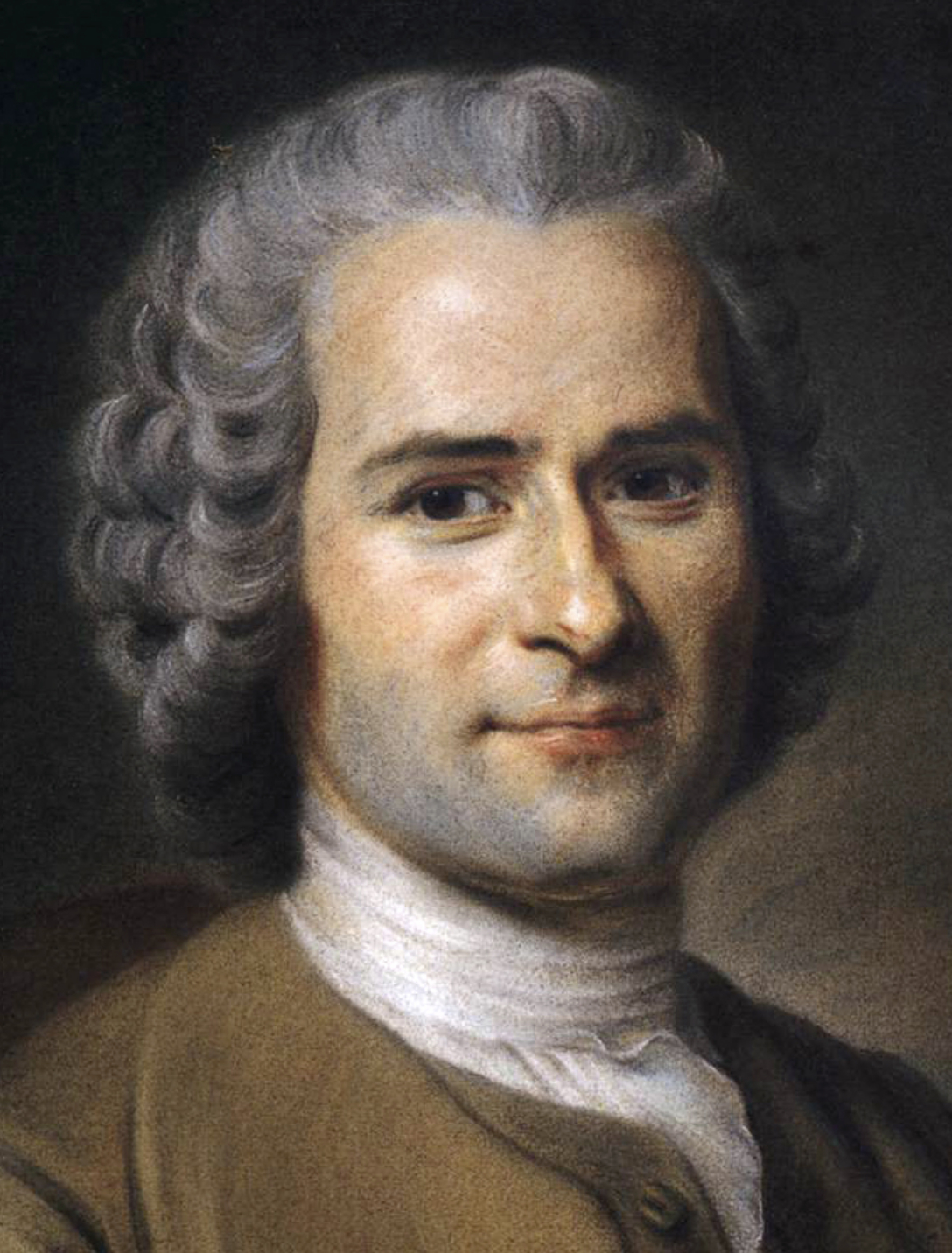

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

On this date in 1712, Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born in Geneva, Switzerland, of French Huguenot parents. His mother died giving birth to him. As a young lad he was apprenticed to an engraver but ran away at age 16 and went into domestic service. His Catholic employer, Mme. De Warens, took him as her lover and allowed him to study literature and philosophy.

In 1741 he moved to Paris and met freethinkers Diderot and D’Holbach, and was asked to write about music for the Dictionnaire Encyclopedique. Rousseau is known for promulgating the idea of the “noble savage” living in a “state of nature,” but intellectual historian Arthur Lovejoy wrote that that misrepresents Rosseau’s thinking.

While living with wealthy patrons, Rousseau worked for eight years writing the novel Julie, ou la nouvelle New Heloise (1760), The Social Contract (1762) and Emile (1762), a treatise on education. The Social Contract introduced the motto “Liberte, egalite, fraternite.” As a Deist with kind words for the gospels, Rousseau was less radical about religion than his friends, perhaps more interested in pursuing his romantic vision of human nature: “Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains.” He believed in a “religion of man.”

Despite Emile’s sympathetic words for the rights of children, Rousseau gave the five illegitimate children he fathered with a hotel maid to foundling homes. His Letters Written to Montaigne (1762) promoted freedom from the church. His arrest was ordered in Paris after publication of Emile and he fled to Switzerland, where officials, in addition to condemning Emile, also condemned The Social Contract and expelled him. Rousseau took refuge in Neuchatel under the King of Prussia but was eventually driven out for his “irreligion.”

He wrote Confessions in England and resettled in Paris in 1770. Freethought biographer Joseph McCabe wrote, “His character was far inferior to that of the ‘irreligious’ Deists of Paris. He was, in fact, the most religious and least virtuous of ‘the philosophers’; far inferior in nobility of character to the Agnostics Diderot and D’Alembert, and more faulty than Voltaire. We must, however, not forget his unhappy circumstances and temperament. He rendered monumental service to his fellows.” (A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists.) (D. 1778)

PHOTO: Portrait of Rosseau by Maurice Quentin de La Tour, 1753.

“Whoever dares to say: ‘Outside the Church is no salvation,’ ought to be driven from the State.

But I am mistaken in speaking of a Christian republic; the terms are mutually exclusive. Christianity preaches only servitude and dependence. Its spirit is so favorable to tyranny that it always profits by such a regime. True Christians are made to be slaves, and they know it and do not much mind: this short life counts for too little in their eyes.”

— Rousseau, "The Social Contract" (1762)

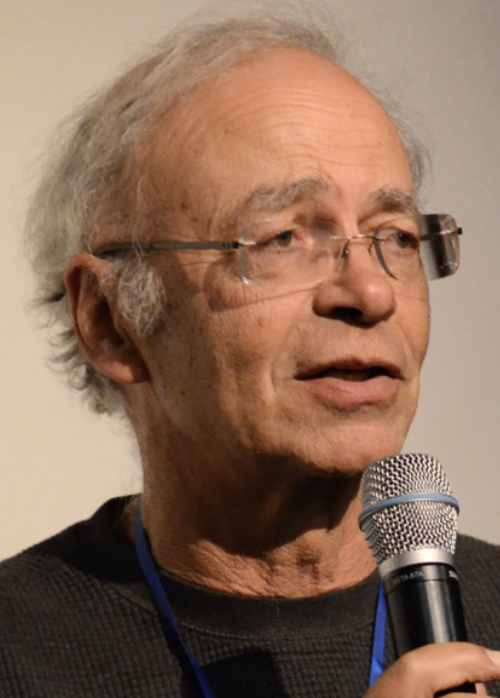

Peter Singer

On this date in 1946, Peter Albert David Singer, philosopher, ethicist, animal rights activist and author was born in Melbourne, Australia. His Jewish parents fled Vienna in 1938 to escape the Nazi takeover. He earned his M.A. from the University of Melbourne in 1969 and got his B. Phil. at the University of Oxford in 1971. In 1977, Singer was appointed to a chair of philosophy at Monash University in Melbourne and subsequently was the founding director of that university’s Centre for Human Bioethics.

Singer was the founding president of the International Association of Bioethics, and with Helga Kuhse, founding co-editor of the journal Bioethics. In 1999 he accepted a professorship at Princeton University and is the DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at the University Center for Human Values at Princeton. He became well-known internationally after the publication of Animal Liberation in 1975.

His influential publications include Practical Ethics (1979), Hegel (1982), The Reproduction Revolution (1984, with Deane Wells), Should the Baby Live? (1985, with Helga Kuhse), How Are We to Live? (1993), Rethinking Life and Death (1994), A Darwinian Left (1999), One World (2000), The President of Good and Evil: The Ethics of George W. Bush (2004), Stem Cell Research: The Ethical Issues (2007), The Life You Can Save: Acting Now to End World Poverty (2009), The Most Good You Can Do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically (2015) and Ethics in the Real World: 82 Brief Essays on Things That Matter (2016).

As a student at the University of Melbourne, Singer was president of the Rationalist Society and editor of its publication The Freethinker. Singer frequently asserts that morality and ethics have no correlation to religious belief. “Atheists and agnostics do not behave less morally than religious believers, even if their virtuous acts rest on different principles. Non-believers often have as strong and sound a sense of right and wrong as anyone, and have worked to abolish slavery and contributed to other efforts to alleviate human suffering.” (Project Syndicate, “Godless Morality,” January 2006.)

He condemns religious intrusion into politics and scientific research. At FFRF’s annual convention in 2004, Singer was a recipient of the Emperor Has No Clothes Award. During his acceptance speech, he said, “Having come to live in America five years ago, I can clearly see why an organization like FFRF is very much needed.”

PHOTO: Singer at the Melbourne Effective Altruism conference in 2015; Mal Vickers photo under CC 4.0.

“I don’t believe in the existence of God, so it makes no sense to me to say that a human being is a creature of God. It’s as simple as that.”

— Singer, Religion & Ethics online magazine (Sept. 10, 1999)

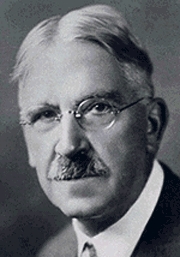

Ernst Bloch

On this date in 1885, German Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch was born in Ludwigshafen in the German Empire. Bloch, the son of a railway worker in a family of assimilated Jews, drew on the work of German philosophers such as Kant, Schilling and Hegel, and developed his opposition to industrial capitalism at a young age. Like many of his colleagues — such as Theodor Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Bertolt Brecht, and Georg Lukacs — his radical politics and Judaism necessitated he flee Germany with the rise of Nazism.

The prevailing concern of Bloch’s major works is the concept of utopia. His first book, Spirit of Utopia (1918), demonstrated the radical ingenuity of his conception of utopia, which he viewed as a present force in the real world.

In his 1968 book Atheism in Christianity, Bloch challenged the notion that atheists must uniformly denounce religious convictions and traditions. Bloch examined Christianity’s social roots, biblical utopianism and anti-authoritarianism, contending there was an unexplored heresy concealed in the bible covertly suggesting that the “good Christian” was also an atheist.

Bloch insisted that skeptics and thinkers move beyond the “crude intellectual polarization” between scientists, philosophers, theorists and believers. (D. 1977)

“[Our church] bristles at see-through blouses, but not at slums in which half-naked children starve, and not, above all, at the conditions that keep three-quarters of mankind in misery. It condemns desperate girls who abort a foetus, but it consecrates war, which aborts millions.”

— Bloch, "Man on His Own: Essays in the Philosophy of Religion" (1959)

Henry David Thoreau

On this date in 1817, Henry David Thoreau was born in Massachusetts. He graduated from Harvard University in 1837, taught briefly, then turned to writing and lecturing. Becoming a Transcendentalist and good friend of Emerson, Thoreau lived the life of simplicity he advocated in his writings. His two-year experience in a hut in Walden, on land owned by Emerson, resulted in the classic Walden: Life in the Woods (1854). During his sojourn there, Thoreau refused to pay a poll tax in protest of slavery and the Mexican War, for which he was jailed overnight.

His activist convictions were expressed in the groundbreaking On the Duty of Civil Disobedience (1849). Thoreau liked to quote Ennius: “I say there are gods, but they care not what men do.” In a diary he noted his disapproval of attempts to convert the Algonquins “from their own superstitions to new ones.”

In a journal he noted wryly that it was appropriate for a church to be the ugliest building in a village, “because it is the one in which human nature stoops to the lowest and is the most disgraced.” (Cited by James A. Haught in 2000 Years of Disbelief.) When Parker Pillsbury sought to talk about religion as Thoreau was dying from tuberculosis, Thoreau replied: “One world at a time.” (D. 1862)

“Your church is a baby-house made of blocks.”

— Thoreau, "On the Duty of Civil Disobedience" (1849)

Jacques Derrida

On this date in 1930, philosopher Jacques Derrida was born in El Bair, French Algeria, to a Sephardic Jewish family. Subjected to the Vichy regime’s oppressive “Jewish laws,” Derrida’s high school studies were interrupted by World War II. In 1949 he moved to Paris to study philosophy at the prestigious École Normale Supérieure.

A prominent figure in the field of post-structural philosophy, Derrida was a pioneer of a method of semiotic analysis called “deconstruction,” perhaps best summarized as “a theory of reading which aims to undermine the logic of opposition within texts.” (A Dictionary of Critical Theory, 1996)

Derrida’s works responded to and deconstructed the Western metaphysical tradition, working in constant dialogue with major philosophical movements of the 20th century, including “Husserlian phenomenology, Saussurean and French Structuralism, and Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis” (Encyclopedia of Contemporary Literary Theory, 1993) A prolific writer, Derrida’s major works include Speech and Phenomena (1967), Of Grammatology (1967), Writing and Difference (1967), Margins of Philosophy (1972) and Acts of Literature (1991).

Religion and its constitutive philology was often subject to Derrida’s deconstructive turn. While Derrida writes, in “Circonfession” (1991), that he would “rightly pass” (je passe à juste titre) for an atheist, the guiding methodology for his work sought ultimately to challenge distinctions between labels like theist and atheist, believer and nonbeliever, and, more broadly, between loaded terms such as faith and reason.

For Derrida, the only “true believer” is one who “[knows] they run the risk of being radical atheists.” (Derrida and Religion: Other Testaments, 2004) It was this paradoxical view of religion, one which aimed to transcend the bounds of rigid, dogmatic faith as well as logic, that defined Derrida’s practice. (D. 2004)

“If I believe in what is beyond being, then I believe as an atheist, in a certain way. However paradoxical it may sound, believing implies some atheism; and I am sure that true believers know this better than others, that they experience atheism all the time. It is part of their belief.”

— "Derrida and Religion: Other Testaments" (2004)

Eric Hoffer

On this date in 1902, Eric Hoffer was born in New York City to German immigrants. By age 5 he was reading in both English and German. Struck by unexplained blindness at age 7, Hoffer regained his sight at 15. The experience of reading deprivation turned him into a nonstop, inveterate reader. He started working as a migrant in California at age 18 and spent most of his life as a dockworker, writing in his spare time, which won him the sobriquet of “the longshoreman philosopher.”

His first book, The True Believer (1951), is a classic. Nine other books were published during his lifetime. His autobiography, Truth Imagined, was published posthumously. (D. 1983)

“The facts on which the true believer bases his conclusions must not be derived from his experience or observation but from holy writ. … To rely on the evidence of the senses and of reason is heresy and treason.”

“The effectiveness of a doctrine should not be judged by its profundity, sublimity or the validity of truths it embodies, but by how thoroughly it insulates the individual from his self and the world as it is. What Pascal said of an effective religion is true of any effective doctrine: It must be ‘contrary to nature, to common sense and to pleasure.’ ”

— Hoffer, "The True Believer" (1951)

Xenophanes of Colophon (Quote)

“The Ethiopians say that their gods are snub-nosed and black, the Thracians that theirs have light blue eyes and red hair.”

— Greek philosopher Xenophanes (c. 570-475 BCE), cited by James A. Haught, ed., "2000 Years of Disbelief: Famous People with the Courage to Doubt" (1996)

Robert M. Pirsig

On this date in 1928, Robert M. Pirsig was born in Minneapolis. He was tested with an IQ of 170 when he was only 9 years old. He enrolled in the University of Minnesota when he was 15, but left to join the army in 1946. Pirsig returned to the university and graduated with a degree in philosophy in 1950, as well as studying philosophy at Banaras Hindu University in India and earning his M.A. in journalism from the University of Minnesota in 1958.

He later became a professor of English rhetoric and composition at the University of Montana, but stopped teaching after he was briefly diagnosed with schizophrenia and depression. He appeared to recover after some institutional care.

In 1974, Pirsig wrote the wildly popular philosophical book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values, in which he detailed a motorcycle trip he took with his son, Chris, while illustrating philosophical ideas. In the book, Pirsig wrote about his theory, “the metaphysics of quality,” which is still widely discussed today.

He married his first wife, Nancy Ann James, in 1954, and they had two sons: Chris, who died in 1979, and Ted. Pirsig married Wendy Kimball in 1978 and the two had a daughter, Nell, born in 1980.

In Pirsig’s novel, Lila: An Inquiry Into Morals (1991), Pirsig wrote, “A person isn’t considered insane if there are a number of people who believe the same way. Insanity isn’t supposed to be a communicable disease. If one other person starts to believe him, maybe two or three, then it’s a religion.” He was quoted in Richard Dawkins’ 2006 book, The God Delusion, as having said more succinctly, “When one person suffers from a delusion, it is called insanity. When many people suffer from a delusion it is called Religion.” D. 2017.

“Religious mysticism is intellectual garbage. It’s a vestige of the old superstitious Dark Ages when nobody knew anything and the whole world was sinking deeper and deeper into filth and disease and poverty and ignorance. It is one of those delusions that isn’t called insane only because there are so many people involved.”

— Pirsig, "Lila: An Inquiry Into Morals" (1991)

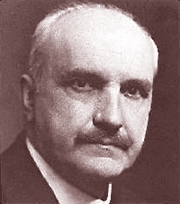

Alain Locke

On this date in 1885, philosopher and author Alain LeRoy Locke, an instrumental figure in the Harlem Renaissance, was born in Philadelphia, the only child of Pliny Ishmael Locke — a law school graduate and the first black employee of the U.S Postal Service — and Mary Hawkins Locke, a teacher. His father died when Locke was 6, when he became even closer to his mother, who was an adherent of Felix Adler.

He was the first African-American Rhodes Scholar and went on to earn a Ph.D. in philosophy from Harvard University. It would be 56 years before another Black was awarded the Rhodes. The family’s religious background was Episcopalian, which Locke later disavowed when he became convinced the Baha’i faith with its “universalist” and humanist views and interracial meetings appealed more to him as a person of color. He would be reprimanded in 1920 while teaching at Howard University for his failure to attend chapel. He had received an assistant professorship there in 1912.

In The Philosophy of Alain Locke: Harlem Renaissance and Beyond (1989), editor Leonard Harris wrote, “Contrary to a Christian doctrine that there exists only one route to salvation, Locke holds that true universality requires a different view of spiritual brotherhood — one compatible with world peace.” In that same book Locke is quoted, “The idea that there is only one true way of salvation with all other ways leading to damnation is a tragic limitation [of] Christianity, which professes the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. How foolish in the eyes of foreigners are our competitive blind, sectarian missionaries!”

In a 2019 profile in The Humanist, Charles Murn wrote that Locke engaged in the culture wars of his time: “He attacked racism, color prejudice, discrimination against minorities, anti-Semitism, eugenics, and imperialism. While he was gay and mentored younger gay men, many of whom were artists, he did not seek to ease restrictions on homosexuality. He called for religious tolerance, yet confronted intolerance by religious leaders.”

Locke possessed a towering intellect (while physically small in stature at 4-foot-11), and after he was fired as chair of Howard’s philosophy department in 1925 for demanding pay equity for Black faculty, focused on publishing The New Negro: An Interpretation. A landmark in Black literature, the anthology contained Locke’s title essay and four more he wrote, along with poetry, art and prose by others, including Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes.

After being reinstated at Howard in 1928, he remained there until retiring in 1953. Leonard Harris notes that between 1912-53, most of the Black philosophy students at U.S. universities were either taught by Locke or by the philosophers he was instrumental in hiring at Howard. He also influenced students during visiting professorships in the mid-1940s at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the New School for Social Research in New York City. The philosophy department at UW-Madison was chaired at that time by Max Carl Otto, one of the earliest and most prominent scientific humanist philosophers.

He died of heart disease in New York City the year after retiring. Engraved on the tombstone under which lay his ashes is “Herald of the Harlem Renaissance” and “Exponent of Cultural Pluralism.” On the back are engraved a nine-pointed Baháʼí star, a bird that’s the national emblem of Zimbabwe, lambda gay rights and Phi Beta Sigma symbols and an African woman’s face set against the sun’s rays. Beneath the images are the Latin words “Teneo te, Africa” (I hold you, Africa). (D. 1954)

“The best argument against there being a God is the white man who says God made him.”

— Locke, quoted in "Alain Locke: Faith and Philosophy" by Christopher Buck (2005)

Philippa Foot

On this date in 1920, philosopher and ethicist Philippa Ruth Foot (née Bosanquet) was born in Owston Ferry, England, to Esther (Cleveland) and William Bosanquet. Her maternal grandfather was U.S. President Grover Cleveland. Her mother, the only child to have ever been born in the White House, married her father, a member of the British Army’s Coldstream Guards and later the manager of a steelworks, in Westminster Abbey in 1918.

Raised in patrician circumstances and educated by governesses and at Somerville College-Oxford, she earned a degree in 1942 in philosophy, politics and economics. She worked as a researcher during World War II at the Royal Institute of International Affairs, sharing a London flat with future novelist Iris Murdoch. She married British military historian M.R.D. Foot in 1945 after he and Murdoch had broken up. The Foot marriage ended without children in 1960.

She started lecturing on philosophy at Somerville in 1947, a year after receiving her master’s, and rose to the positions of vice principal and senior research fellow before retiring in 1988. In 1974 she became a professor of philosophy at the University of California in Los Angeles, where she retired in 1991.

Foot posed her famous “trolley problem” in 1967, capturing the imagination of scholars outside her discipline. Described by The New York Times, it used “a series of provocative examples, the moral distinctions between intended and unintended consequences, between doing and allowing, and between positive and negative duties — the duty not to inflict harm weighed against the duty to render aid.

“The most arresting of her examples, offered in just a few sentences, was the ethical dilemma faced by the driver of a runaway trolley hurtling toward five track workers. By diverting the trolley to a spur where just one worker is on the track, the driver can save five lives.” The problem took on a life of its own, inspiring variations such as “the fat man” and a host of others.

“Foot was a giant of moral philosophy,” said her 2010 obituary in Philosophy Now magazine. “Her books include ‘Natural Goodness’ and two collections of essays, ‘Virtues and Vices: And Other Essays in Moral Philosophy’ and ‘Moral Dilemmas: And Other Topics in Moral Philosophy.’ These three relatively slender volumes represent decades of work at the very highest levels of philosophical sophistication.” She also wrote and lectured extensively on free will and determinism and was a pioneer in the field of virtue ethics.

Nikhil Krishnanis, a lecturer in philosophy at the University of Cambridge, described her as “temperamentally unsympathetic both to religious solutions and to mystical ones” and as “a secular philosopher of broadly liberal opinions.” (Aeon magazine, Nov. 28, 2017)

To others she was a rationalist or an atheist. Foot’s personal views on religion were nuanced and not worn on her sleeve. Nor was she simply dismissive of religion. In an interview with Philosophy Now editor Rick Lewis (Fall 2001), she said:

“What is right and wrong for different societies will often be different. Things will be justifiable in one situation and not in another. And, of course, one of the determining factors will be religion, what people believe the gods will do; will offend them or bring their wrath down on the community. After all, it would be totally wrong to bring the wrath of the gods on your community – so religion comes in, too.”

But her skepticism lurked beneath the surface: “I once asked [Oxford Catholic philosopher Michael Dummett], ‘What happens when your argument goes one way and your religious belief goes the other?’ And he said, ‘How would it be if you knew that something was true? Other things would have to fit with it.’ That I take it is the clue, that they think they know that and could as little deny it as that I am talking to someone now.” (The Philosophers’ Magazine, 2003)

She died at home in Oxford, England, on her 90th birthday. (D. 2010)

“Foot herself, however, is a ‘card-carrying atheist.’ ”

— "Interview With Philippa Foot," The Philosophers' Magazine, Issue 21, 2003

Denis Diderot

On this date in 1713, philosopher Denis Diderot was born in Langres, France, and was destined by his lower-class family for the priesthood. At 13 he was tonsured and titled “abbe.” Continuing his studies in Paris, Diderot abandoned his faith when exposed to science and freethought views, evolving gradually from deist to atheist. In his Essay on the Merits of Virtue (1745), Diderot noted: “From fanaticism to barbarism is only one step.”

Diderot anonymously wrote Pensees philosophiques (Philosopical thoughts) in 1746, which was ordered burned in public. In it he wrote, “Skepticism is the first step toward truth.” After An Essay on Blindness was published in 1749, Diderot spent three months in jail for atheism, which taught him to only circulate his rationalist writings privately. His Interpretation of Nature (1753) sets out the scientific method. His treatises on aesthetics led him to be called the first art critic. His novels include La Religieuse (published posthumously in 1796), which took an unstinting look at the sexually corrupting forces of monasticism and fanaticism.

Diderot was the commissioned editor of the first major encyclopedia. He worked with rationalist contributors, including Voltaire, on this monument to the Age of Enlightenment, compiling human achievements in knowledge for nearly 30 years, while facing Catholic opposition. The 17 volumes of text and 11 of illustrations were published between 1751-72. The publisher at one time was imprisoned. Catherine the Great offered Diderot refuge, which he declined, but he accepted her grand gesture of purchasing his library and bequeathing it to him for life in 1766.

In 1773 he made the arduous journey to Russia to thank her, with hopes of setting up a Russian university. The trip disappointed him in her reign and broke his health. D. 1784.