poets

Carl Sandburg

On this date in 1878, poet and Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer Carl August Sandburg was born in Galesburg, Ill., to parents of Swedish-Lutheran heritage. The second of seven children, he quit school after the eighth grade and worked at a variety of jobs such as milkman, porter, bricklayer and farm laborer for the next decade. In 1897 he lived as a hobo. He would later perform the folk songs he learned on the road and compiled them into two song books.

Sandburg enlisted in the U.S. Army during the Spanish-American War in 1898 and was stationed in Puerto Rico. After a two-week stint at West Point, he failed a math and grammar exam and left the military academy. He then attended the Universalist-founded Lombard College in Galesburg. Attracted to labor concerns, he became an organizer for the Wisconsin Social Democratic Party and met his wife-to-be Lilian Steichen at party headquarters in Milwaukee. They were wed in 1908 and had three daughters, Margaret, Jane and Helga.

He worked from 1910-12 as a secretary for Emil Seidel, Milwaukee’s socialist mayor, then joined the Chicago Daily News as a reporter. Much of his poetry, such as “Chicago,” focused on the city he famously described as “Hog Butcher for the World/Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat/Player with Railroads and the Nation’s Freight Handler,/Stormy, Husky, Brawling, City of the Big Shoulders.”

Sandburg earned Pulitzers for the 103-poem Corn Huskers (1919), Abraham Lincoln: The War Years (1940) and Complete Poems (1951). His Lincoln work and the earlier Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years (1926) became very influential histories. He was also remembered by generations of children for his Rootabaga Stories (1922). His 1927 anthology, The American Songbag, enjoyed enormous popularity, going through many editions. He often sang and accompanied himself on guitar at lectures and poetry recitals.

A lifelong Unitarian, he died at age 89 in his longtime home in Flat Rock, N.C. (D. 1967)

"To work hard, to live hard, to die hard, and then to go to Hell after all would be too damned hard."

— Sandburg, from his book-length poem "The People, Yes" (1936)

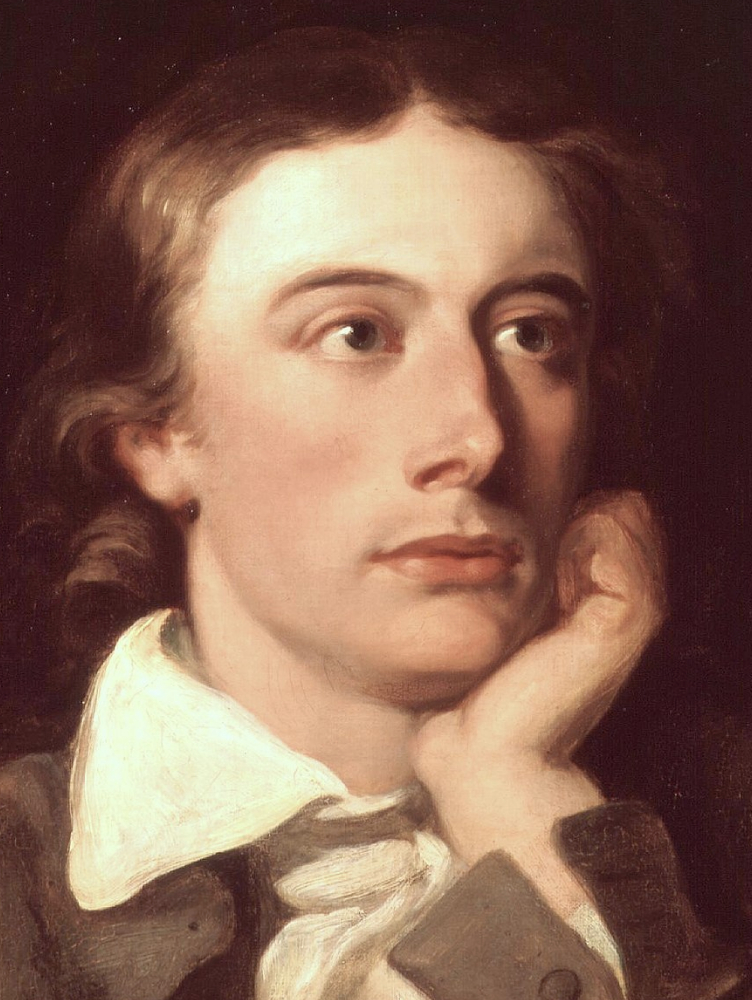

Molière

On this date in 1622, playwright and poet Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, who adopted the stage name Molière as an actor, was born in Paris. His father was an upholsterer/valet to King Louis XIII. Molière studied philosophy in college, started a Parisian acting troupe and toured the provinces with it for many years, acting, directing and writing.

As a favorite of King Louis XIV, he produced a succession of 12 popular comedies still being performed, including “The School for Wives” (1662), “Don Juan” (1665), “Le Misanthrope” (1666) and “Tartuffe” (1667), all irreverent and increasingly irreligious. “Tartuffe,” a satire on religiosity, originally featured a hypocritical priest. Although Molière rewrote Tartuffe’s profession to avoid scandal, some religious officials nevertheless called for him to be burned alive as punishment for his impiety. He would claim he was attacking hypocrisy more than religion.

He married actress Armande Bejart when she was 19 and they had a daughter, Esprit-Madeleine, in 1665. Becoming ill while playing the lead in his play “Le Malade imaginaire” (“The Imaginary Invalid”), Molière insisted on finishing the show, after which he died. He had long suffered from tuberculosis. The church refused to bury him in sanctified ground because he had not received the last rites and did not renounce his profession as an actor before his death. When the king intervened, the archbishop of Paris allowed him to be buried only after sunset among the suicides’ and paupers’ graves with no requiem Masses permitted in the church. (D. 1673)

“Though living in an age of reason, he had the good sense not to proselytize but rather to animate the absurd …”

— Encyclopedia Britannica entry on Molière

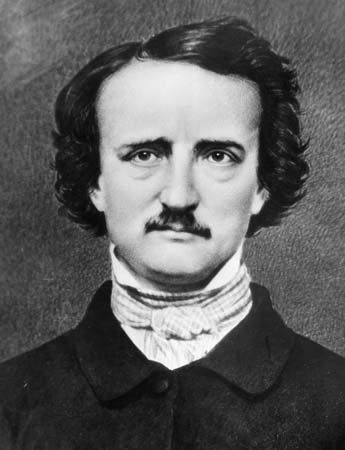

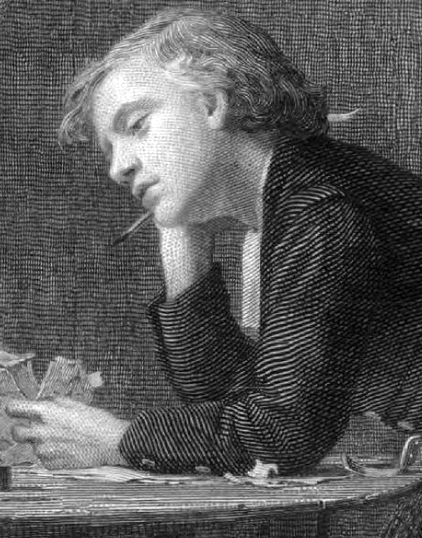

Edgar Allan Poe

On this date in 1809, writer Edgar Allan Poe was born in Boston. When his parents, both actors, died before he was 3, he was adopted by John Allan, who educated him in London and Virginia. Poe attended the University of Virginia for one year before dropping out. He began writing poetry, served in the U.S. Army for two years and was awarded a prize for a short story in 1833. He moved to Baltimore and lived with his widowed aunt and her daughter, Virginia, and began editing the Southern Literary Messenger.

He married his 13-year-old cousin, Virginia Clemm, in 1836 and moved with her to New York City and Philadelphia, living in poverty while in search of better writing positions. His only complete novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838), was followed by Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (1839), The Pit and the Pendulum (1842), The Tell-Tale Heart (1843) and other works classified as tales. Poe is considered a pioneer of thrillers and detective fiction, writing The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841), The Mystery of Marie Roget (1842), The Gold Bug (1843), and The Purloined Letter (1844).

The Raven, and Other Poems, was published to great acclaim in 1845. Virginia died of tuberculosis in 1847, inspiring Poe’s famous poem “Annabel Lee.” His “prose poem” Eureka, according to freethought historian Joseph McCabe, “embodies a Pantheism which is not far removed from Agnosticism.” (A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists, 1920.) In it, Poe wrote that we know nothing about the nature of God, that nature and God are the same, and there is no personal immortality.

He died unexpectedly at age 40 in 1849 in Baltimore. The cause of his death was never resolved and was attributed at the time by newspapers to “congestion of the brain” or “cerebral inflammation,” common euphemisms for alcoholism.

"Let us begin, then, at once, with that merest of words, ‘Infinity.’ This, like ‘God,’ ‘spirit,’ and some other expressions of which the equivalents exist in all languages, is by no means the expression of an idea — but of an effort at one. It stands for the possible attempt at an impossible conception."

— Poe, "Eureka: A Prose Poem" (1848)

Robert Burns

On this date in 1759, Robert Burns was born to a poor farming family in Alloway, Scotland, the setting for his poem “Tam o’ Shanter.” He once described himself as being full of “enthusiastic, idiot piety” as a boy and early on questioned religious belief despite being forced to read “A Manual of Christian Belief,” written by his father. He directed his pen against Calvinism in his first poem, “Two Herds” (1785), a satire on rival theology, followed by “Holy Willie’s Prayer” and “Holy Fair.”

Biographers, unsure whether to call Burns an agnostic or a deist, agree he rejected Calvinism (“I am in perpetual warfare with that doctrine.” (Letter to Mrs. Dunlop, Aug. 2, 1788.) He also criticized churches (“Courts for cowards were erected / Churches built to please the priest”), doubted the existence of God (“O Thou Great Being! what thou art / Surpasses me to know”) and the existence of an afterlife.

In his poem “To a Louse on Seeing One on a Lady’s Bonnet at Church,” Burns famously wrote, “O wad some pow’r the giftie gie us / to see oursels as others see us! / It wad frae monie a blunder free us / An’ foolish notions.” The celebrated “Ploughman Poet” bequeathed to the world the lyrics of “Auld Lang Syne,” striking a welcome secular note with which to end the Western New Year, “We’ll take a cup o’ kindness yet / For auld lang syne.”

Burns had 12 children with four women, including nine by his wife Jean Armour. Of the nine, only three survived to adulthood. When he died at age 37 of heart disease, 10,000 people attended the burial. In 2009 the British television channel STV conducted a public vote on who was “The Greatest Scot” of all time. Burns won narrowly over William Wallace. (D. 1797)

“[Burns] lives in darkness and in the shadow of doubt. His religion, at best, is an anxious wish; like that of Rabelais, ‘a great Perhaps.’ "

— "Carlyle's Essay on Burns," ed. Homer B. Sprague (1898)

Langston Hughes

On this day in 1901, Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Mo. (Research belatedly found in 2018 that Hughes, who had claimed to be born in 1902, had shaved a year off of his age.) For four decades he chronicled the black experience and perspective in powerful poetry, fiction, nonfiction and children’s books. The Nation magazine published his influential essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” (1926), in which Hughes advocated racial pride and independent artistry, giving the Harlem Renaissance its due. He enrolled at Columbia University and finished his degree at Lincoln University in Oxford, Pa., in 1926.

His first book of poetry was The Weary Blues, his first novel was Not Without Laughter (1930) and his first book of short stories was The Ways of White Folks. His play Mulatto (1935) ran successfully on Broadway. His autobiography, The Big Sea, came out in 1940, followed in 1956 by I Wonder As I Wander. Among his many other books was Jim Crow’s Last Stand (1943).

Hughes’ satire on corruption in black storefront churches, Tambourines to Glory (1963), was not popular with black clergy. Hughes, who traveled widely all his life, had visited the Soviet Union and was forced to appear before a congressional committee in 1953 duing the “Red scare.” He wrote a column for 20 years for the Chicago Defender.

Hughes had a complicated relationship with religion, according to Wallace Best, author of Langston’s Salvation: American Religion and the Bard of Harlem (2017). Hughes strongly disagreed with characterizations of him as anti-religious or atheist while reserving the right to criticize dogma and the Christian church. Best called him a “thinker about religion.”

He never married and was generally seen by contemporaries and later by scholars and critics as gay or perhaps asexual. He died in New York City at age 66 from complications after abdominal surgery related to prostate cancer. (D. 1967)

PHOTO: Hughes photographed by Gordon Parks in 1943.

Listen, Christ,

You did alright in your day, I reckon—

But that day’s gone now.

They ghosted you up a swell story, too,

Called it Bible—

But it’s dead now.

The popes and the preachers’ve

Made too much money from it.

They’ve sold you to too many.— from Hughes' poem "Goodbye Christ" (1932)

Christopher Marlowe

On this date in 1564, Christopher “Kit” Marlowe was born. The poet and dramatist, who authored “Tamburlaine” (c. 1587) and “Tragedy of Dr. Faustus” (c. 1588), was a contemporary of William Shakespeare. Educated at Cambridge, Marlowe worked as an actor and dramatist. One of his enduring poems is the “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love” with its opening line “Come live with me and be my love.”

Marlowe, with Sir Walter Raleigh and others, established the first Rationalist group in English history, according to freethought historian Joseph McCabe. Marlowe was derided as an “atheist” by several contemporary political enemies. His character Faustus concludes “hell’s a fable,” and his villain-hero Tamburlaine burns the Quran and challenges Muhammad to “work a miracle.” The Privy Council had decided to prosecute Marlowe for heresy, accusing him of writing a document denying the divinity of Christ, a few weeks before his death in a barroom brawl. There has been endless speculation over Marlowe’s short life and violent death at age 29. (D. 1593)

"[H]e counts religion but a childish toy,

And holds there is no sin but ignorance."— Marlowe, "The Jew of Malta" (c. 1589)

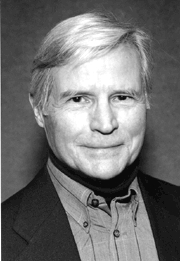

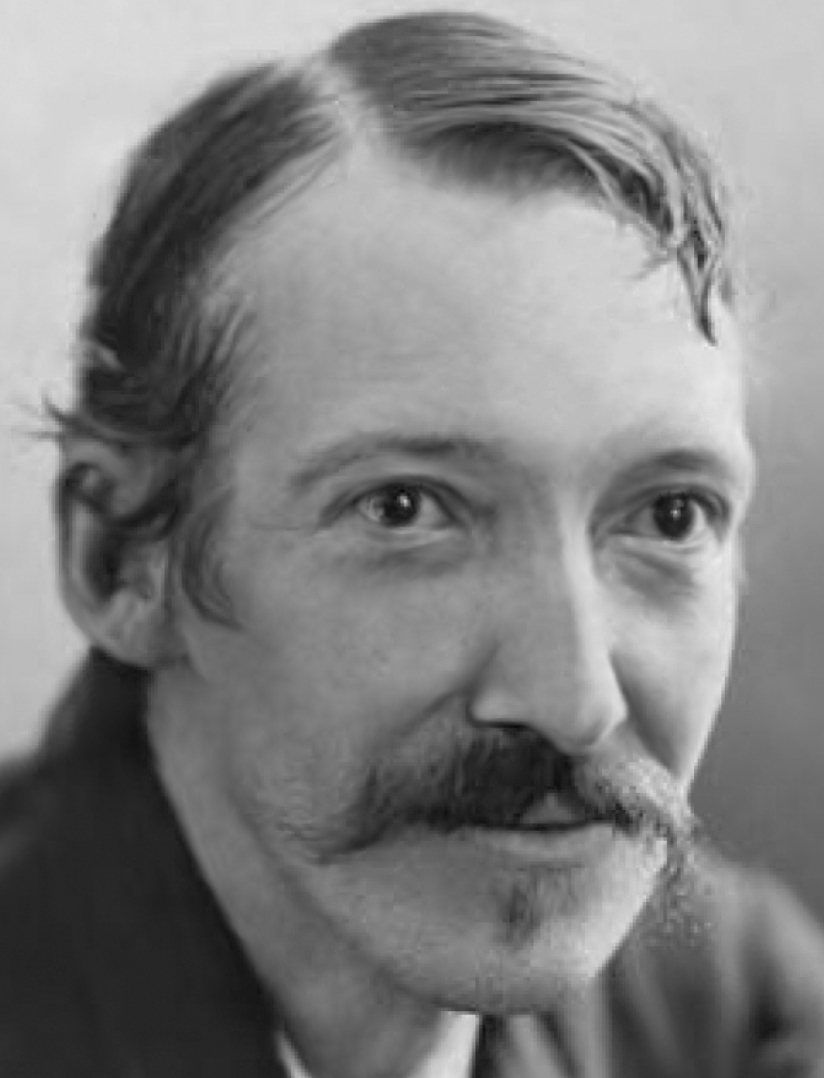

Philip Appleman

On this date in 1926, Philip Dean Appleman was born in Kendallville, Ind. Appleman, a Distinguished Professor Emeritus at Indiana University, was considered the “Poet Laureate of Humanism and Freethought” and published nine volumes of poetry, three novels (two with explicitly freethinking themes) and six volumes of nonfiction. His work often skewered religious belief, including the bible. One of his most notable volumes was New and Selected Poems, 1956-1996, which included his powerful freethought poetry from the acclaimed Let There Be Light: Poems.

Appleman, a Darwin scholar and aficionado, was the editor of the widely used Norton Critical Edition, Darwin, and the Norton Critical Edition of Malthus’ Essay on Population. Appleman’s poetry and fiction have won many awards, including a fellowship in poetry from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Humanist Arts Award from the American Humanist Association, the Friend of Darwin Award from the National Center for Science Education, and the Castagnola Award from the Poetry Society of America.

His writing appeared in Harper’s Magazine, The Nation, New Republic, The New York Times, Paris Review, Partisan Review, Poetry, Sewanee Review and Yale Review. He was married for 67 years to playwright Marjorie Appleman, née Haberkorn. A great friend of FFRF, he spoke at three national conventions and was an interview guest on several broadcasts over the years. He died at age 94. Read a lovely tribute here in FFRF’s Freethought Today. (D. 2020)

O Karma, Dharma, Pudding and Pie

O Karma, Dharma, pudding and pie,

gimme a break before I die:

grant me wisdom, will, & wit,

purity, probity, pluck, & grit.

Trustworthy, helpful, friendly, kind,

gimme great abs and a steel-trap mind,

and forgive, Ye Gods, some humble advice —

these little blessings would suffice

to beget an earthly paradise:

make the bad people good —

and the good people nice;

and before our world goes over the brink,

teach the believers how to think.Last-Minute Message for a Time Capsule

I have to tell you this, whoever you are:

that on one summer morning here, the ocean

pounded in on tumbledown breakers,

a south wind, bustling along the shore,

whipped the froth into little rainbows,

and a reckless gull swept down the beach

as if to fly were everything it needed.

I thought of your hovering saucers,

looking for clues, and I wanted to write this down,

so it wouldn’t be lost forever —

that once upon a time we had

meadows here, and astonishing things,

swans and frogs and luna moths

and blue skies that could stagger your heart.

We could have had them still,

and welcomed you to earth, but

we also had the righteous ones

who worshipped the True Faith, and Holy War.

When you go home to your shining galaxy,

say that what you learned

from this dead and barren place is

to beware the righteous ones.— From "Karma, Dharma, Pudding & Pie" (2009) and "New and Selected Poems, 1956-1996"

Elizabeth Bishop

On this date in 1911, American poet and short-story writer Elizabeth Bishop was born in Worcester, Mass. Bishop, an only child, lost both of her parents when she was very young. Her father died when she was only a year old and her mother was committed to a mental institution when she was 5, dying there 18 years later. For the rest of her childhood, she was passed between relatives who were able to take care of her. She first lived with her maternal grandparents in Nova Scotia but soon moved to live with her paternal relatives in Worcester and South Boston. They were concerned about the limited education and financial resources available in Nova Scotia.

She attended Walnut Hills School for Girls, an independent boarding school for the arts and went on to earn her B.A. in English from Vassar College. At Vassar, she helped found the rebellious, student literary newspaper Con Spirito. It merged after three issues with the Vassar Review.

After graduation, Bishop traveled to numerous countries, including France, Spain, Ireland, Italy and several in North Africa. She continued to travel and live all over the world for much of her life. She published 101 poems, painstakingly crafting each piece. Her poetry incorporates descriptions of her journeys abroad, in addition to struggles to find a sense of belonging and the human experiences of grief and longing. “Her poetry speaks to many issues that are urgent today: gender identity, our difficult relationship to foreign cultures and postcolonial realities, the way that science and reason can sometimes do violence to the world,” wrote Bonnie Costello, author of Elizabeth Bishop: Questions of Mastery. As a metaphysically minded poet, Bishop is featured in The Joy of Secularism: 11 Essays for How We Live Now, which discusses her particular interest in Darwin’s work and her views on secularism.

In 1949 she was appointed to serve as U.S. Poetry Laureate Consultant to the Library of Congress for the year. Bishop won several awards, including the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1956, the National Book Award for Poetry in 1970 and the Neustadt International Prize for Literature in 1976. In her later years, she lectured at the University of Washington, at Harvard University for seven years and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Bishop died in her Boston apartment of a cerebral aneurysm. (D. 1979)

"[Darwin] is one of the people I like best in the world."

— Bishop letter of June 3, 1971, telling James Merrill she was reading Darwin; cited in "The Joy of Secularism: 11 Essays for How We Live Now," ed. George Levine (2011)

Alice Walker

On this date in 1944, novelist, poet and self-described “Earthling” Alice Malsenior Tallulah-Kate Walker was born in Eatonton, Georgia, the youngest of eight children in a sharecropping family. Blinded in one eye during a childhood accident, she went on to become valedictorian at her high school and attended both Spelman College and Sarah Lawrence College on scholarships. Walker graduated from Sarah Lawrence in 1965. She worked on voter registration drives in the 1960s and married fellow civil rights worker Melvyn Leventhal in 1967. They had a daughter, Rebecca, in 1970 and divorced in 1976.

Her first book of poetry was published in 1970. Walker edited I Love Myself When I Am Laughing and Then Again When I Am Looking Mean and Impressive: A Zora Neale Hurston Reader in 1979, introducing and popularizing Hurston to a new generation.

The Color Purple, Walker’s bestselling 1982 novel, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1983 and was turned into a popular movie by Steven Spielberg. Walker introduced the term “womanist” to the feminist movement to describe African-American feminism. Her books of essays include In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens: Womanist Prose (1983), Alice Walker Banned (1996) and Anything We Love Can Be Saved: A Writer’s Activism (1997).

Walker’s views on religion are expressed in “The Only Reason You Want to Go to Heaven Is That You Have Been Driven Out of Your Mind (Off Your Land and Out of Your Lover’s Arms): Clear Seeing Inherited Religion and Reclaiming the Pagan Self” (anthologized in Anything We Love Can Be Saved). Raised as a Methodist by devout parents, early in life she observed church hypocrisy, especially the silencing of the women who cleaned the church and kept it alive. “Life was so hard for my parents’ generation that the subject of heaven was never distant from their thoughts. … The truth was, we already lived in paradise but were worked too hard by the land-grabbers to enjoy it.”

In The Color Purple, the protagonist rebels against a God who [vernacular ahead] “act just like all the other mens I know. Trifling, forgitful and lowdown.” Walker, rebelling against the misogyny of Christian teachings and the imposition of a white religion upon the enslaved, wrote: “We have been beggars at the table of a religion that sanctioned our destruction.”

Walker added: “All people deserve to worship a God who also worships them. A God that made them, and likes them. That is why Nature, Mother Earth, is such a good choice. Never will Nature require that you cut off some part of your body to please It; never will Mother Earth find anything wrong with your natural way.”

“It is chilling to think that the same people who persecuted the wise women and men of Europe, its midwives and healers, then crossed the oceans to Africa and the Americas and tortured and enslaved, raped, impoverished, and eradicated the peaceful, Christ-like people they found. And that the blueprint from which they worked, and still work, was the Bible."

— "Anything We Love Can Be Saved" (1997)

Amy Lowell

On this date in 1874, poet Amy Lawrence Lowell was born in Brookline, Mass. Her father, a cousin of James Russell Lowell, was also related to Robert Lowell. Amy grew up in a house her father dubbed “Sevenels” (because seven Lowells lived there). Lowell at first had a British governess and became famous in her family for her creative misspellings. As a popular debutante, known for her dancing and conversational style, she had no less than 60 dinners thrown for her.

Because it was not considered “proper” by her family for young women to go to college, she was denied a higher education, but made use of her family’s extensive library to educate herself. After a failed engagement and growing obesity, probably stemming from a glandular condition, Lowell was exiled to Egypt in 1897-98 to help her forget her troubles and also lose weight. The imposed spartan regimen nearly killed her.

She started writing poetry in 1902 and met actress Ada Dwyer Russell in 1912, with whom she had a “Boston marriage” for the rest of her life. Her first of several books of poems, Men, Women & Ghosts, was published in 1916. Lowell wrote Tendencies in Modern American Poetry (1917). Her biography of John Keats appeared in 1925. What’s O’Clock, posthumously published in 1925, was awarded a $1,000 Pulitzer Prize for the best volume of verse published during the year by an American author.

Lowell penned more than 650 poems before her death from a cerebral hemorrhage at age 51. (D. 1925)

And every year when the fields are high

With oat grass, and red top, and timothy,

I know that a creed is the shell of a lie.— Lowell's poem "Evelyn Ray" from "What's O'Clock" (1925)

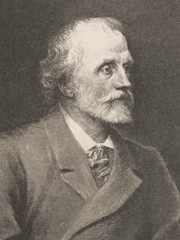

George Meredith

On this date in 1829, novelist and poet George Meredith was born in Portsmouth, England. His mother died when he was 5 and when his father later had to declare bankruptcy, George was sent to live with relatives. At 15 he had his only formal education when he was sent to a Moravian school for less than two years. Apprenticed to a solicitor, he jettisoned legal work when he began writing articles and poetry for magazines. Poems (1851) was followed by The Shaving of Shagpat (1855), neither very successful. He wrote 19 novels, the last published posthumously in 1910.

He worked as a reporter, read for a book publishing company and was a war correspondent. Among the writers he encouraged were Thomas Hardy and Olive Schreiner. He married widow Mary Ellen Nichols, who was seven years older than him, in 1849. She became the role model for many of his heroines. It was not a successful marriage. She eloped with an artist in 1858, leaving their one surviving child with him, and died three years later.

The Ordeal of Richard Feverel, (1859), a semi-autobiographical account of his marriage, had better success. Meredith married Marie Vulliamy in 1864. Other books include The Egoist (1879) and Diana of the Crossroads (1885). He was quoted in Fortnightly Review in July 1909 saying: “The man who has no mind of his own lends it to the priests.” He was nominated seven times for the Nobel Prize in Literature. (D. 1909)

"When I was quite a boy, I had a spasm of religion which lasted about six weeks, during which I made myself a nuisance in asking everybody whether they were saved. But I never since have swallowed the Christian fable."

— Meredith, quoted in "Memories" by Edward Clodd (1916)

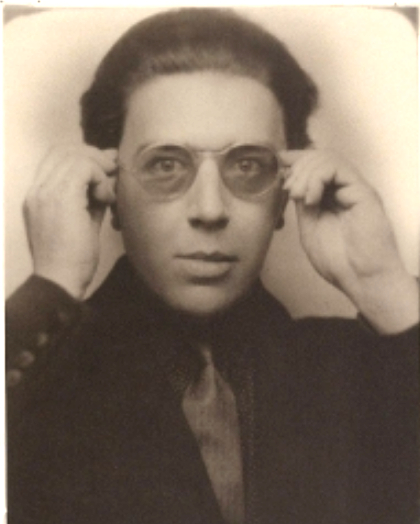

André Breton

On this date in 1896, French poet and writer André Breton was born in Tinchebray, France. He wrote poetry early in life but formally studied medicine and later psychiatry. He met Sigmund Freud in 1921 and his later writings were inspired in part by Freud’s ideas. Breton is considered, along with Salvador Dalí and others, a founder of surrealism. His Surrealist Manifesto was published in 1924, and that same year he influenced the founding of the Bureau of Surrealist Research.

The French government in 1938 sent Breton on a cultural commission to Mexico, where he met Leon Trotsky, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. Breton and Trotsky wrote a manifesto calling for freedom in art, “Pour un art révolutionnaire indépendent” (“Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art”). Breton joined the French Army medical corps during World War II, at which time the Vichy government banned his writings. He escaped to the United States in 1941. Upon his return to Paris in 1946, he became a strong proponent of anarchism and founded a new group of surrealists.

Breton was extensively published. Some of his works include If You Please (1920), The Magnetic Fields (1920), A Corpse (1924), Nadja (1928), The Second Manifesto of Surrealism (1920), The Automatic Message (1933), What Is Surrealism (1934), Manifestoes of Surrealism (1955) and The Magic Art (1957). In André Breton: Arbiter of Surrealism (1967), Clifford Browder noted: “Breton was unflinching in his rejection of mysticism, which he associated with the worship of a superior power outside the human mind; for him the Surrealist merveilleux contained no trace of religious mystery.”

Breton was married three times. He met his third wife while in exile in the U.S. He had one daughter, Aube, with his second wife. Breton died in 1966 at age 70 and is buried in Paris.

"Everything that is doddering, squint-eyed, vile, polluted and grotesque is summoned up for me in that one word: God!"

— Breton, "Surrealism and Painting" (1928)

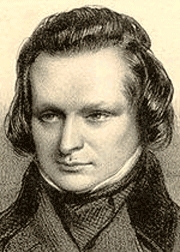

James Russell Lowell

On this date in 1819, poet James Russell Lowell was born in Cambridge, Mass., the son of a Unitarian minister in a family which went back eight generations in America. Lowell was one of the “Fireside Poets,” a group of New England writers that included Longfellow, Whittier and Holmes. Lowell earned his B.A. in 1838 and his L.L.B. in 1840 from Harvard. An ardent abolitionist, he left the law for literature, editing several journals.

He edited the Atlantic Monthly (1857-61) and the progressive North American Review (1864-72). A professor at Harvard for nearly 20 years, he also served as a minister to Spain and Great Britain. The poet wrote A Fable for Critics (1848), The Biglow Papers (serialized articles published in book form in 1848 and 1867) and The Vision of Sir Launfal (“And what is so rare as a day in June?”) in 1848.

Although Lowell’s poetry contains religious views that were conventionally 19th-century Unitarian, rationalist biographer Joseph McCabe suggested that, based on his later remarks, Lowell became agnostic. His later poetry included “The Cathedral “(1870), which dealt with the conflicting claims of religion and modern science.

He married the poet Maria White in 1844. They had four children, only one of whom survived childhood, before she died in 1853. He married Frances Dunlap in 1857. She died in 1885, six years before his death in 1891 at age 72.

"Toward no crimes have men shown themselves so cold-bloodedly cruel as in punishing differences of belief."

— Lowell, "Literary Essays, Vol. II: Witchcraft" (1891)

Joan Konner

On this date in 1931, journalist Joan Barbara Konner was born in Paterson, N.J., the daughter of Martin Weiner, who was in the textile business, and the former Tillie Frankel, an artist. She received her B.A. from Sarah Lawrence College in 1951. She earned a master’s in jounalism from Columbia in 1961 when she was 30 after raising two daughters, Rosemary and Catherine. Her marriage ended in divorce, and Catherine died in 2003.

She was hired as a journalist for the Bergen Record, where she worked on the women’s page. She left in less than two years to work at WNBC-TV, where she was a writer and producer of many documentaries. She became executive producer of “Bill Moyers Journal” during the 1980s and later was president and executive producer of Moyers’ production company, Public Affairs Television. She helped produce the acclaimed six-part docuseries “Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth” for Moyers. She worked with Alvin Perlmutter on the series and married him in 1994.

Konner ended her career in public television as executive producer for national news and public affairs for WNET/Thirteen in New York. She returned to Columbia in 1988 to become the first female dean of the Columbia School of Journalism. She was also publisher of the Columbia Journalism Review until 2000.

She wrote books on religion from the freethought point of view, such as The Atheist Bible: An Illustrious Collection of Irreverent Thoughts (2007), and You Don’t Have to Be a Buddhist to Know Nothing: An Illustrious Collection of Thoughts on Naught (2009) and is known for producing over 50 documentaries and television series that focus on ideas and beliefs. “I myself was born Jewish and I have great respect for that, but if you ask me to name what I’ve learned the most from — and what seems to guide my own behavior now — I say I’m a ‘Trans-Zen-Jewish-Quak-alist.’ ” (Read the Spirit interview, March 16, 2010.)

Konner won numerous awards and honors throughout her lengthy career, including 16 Emmys, a Peabody Award, the New Jersey Presswomen’s Lifetime Achievement Award and the New York Newswomen’s Award for Best Documentary. She died of leukemia at age 87 in Manhattan in 2018.

“I see myself as a journalist if anything. I don't call myself an agnostic but I do recognize that I will never know.”

— Konner interview in the online magazine Read The Spirit (March 16, 2010)

Victor Hugo

On this date in 1802, author Victor Marie Hugo was born in Besançon, France, the son of a Napoleonic officer. By 17 he had earned three prizes for poetry at Toulouse. King Louis XVIII awarded Hugo a royal pension after his Odes and Poetry appeared (1822). His first drama, “Cromwell,” was published in 1827.

After devoting nearly two decades to stage writing, Hugo turned to fiction. His novel, known in English as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, was published in 1831 and featured a villainous priest. It has been turned into several movies and dramatizations, including a Disney cartoon (which interestingly turned villain Claude Frollo into a layperson). Les Misérables was published in 1862 in 10 languages. The epic tale has spawned several movies and stage productions, including its Broadway debut in 1987.

Hugo was forced to flee to Belgium after Napoleon III’s coup d’etat in 1851. He eventually returned to France when the republic was proclaimed and was elected a senator in 1876. Although his religious views wavered over his long and tempestuous life, Hugo was anti-clerical, freedom-loving and generally considered to have been a rationalistic deist.

He married Adèle Foucher in 1822 and they had five children before her death in 1868. He suffered a mild stroke in 1878 and recovered. He died of pneumonia in Paris at age 83. (D. 1885)

"An intelligent hell would be better than a stupid paradise."

— from Hugo's play "Ninety-three" (1881)

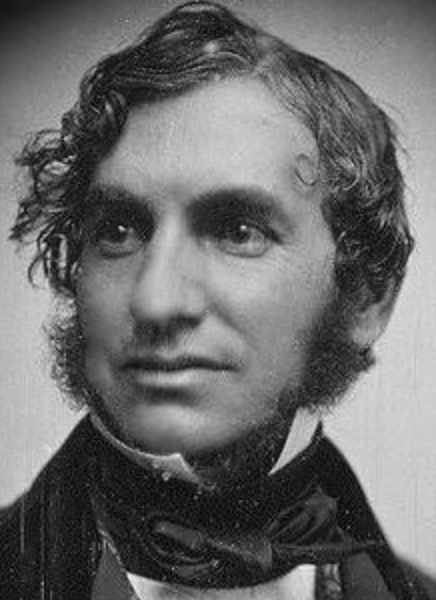

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

On this date in 1807, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine, the son of an attorney who was also a member of Congress. Longfellow’s mother was a descendant of John Alden of the Mayflower. He started writing poems at 13 and graduated from Bowdoin College, where classmates included Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Longfellow traveled widely, married twice (both wives dying tragically) and became professor of modern languages at Harvard. He was the 19th century’s most popular American poet. His poems included “The Village Blacksmith” and “Paul Revere’s Ride,” as well as “Evangeline” (1847) and “The Song of Hiawatha” (1855).

William Ellery Channing reputedly said of Longfellow, a lifelong Unitarian, that “he did not belong to any one sect but rather to the community of those free minds who loved the truth.” A father of six children, he died at age 75 in Cambridge, Mass. (D. 1882)

PHOTO: Longfellow, circa 1850.

"I think that as he grew older his hold upon anything like a creed weakened, though he remained of the Unitarian philosophy concerning Christ. He did not latterly go to church."

— William Dean Howells, "Literary Friends and Acquaintance; a Personal Retrospect of American Authorship" (1901)

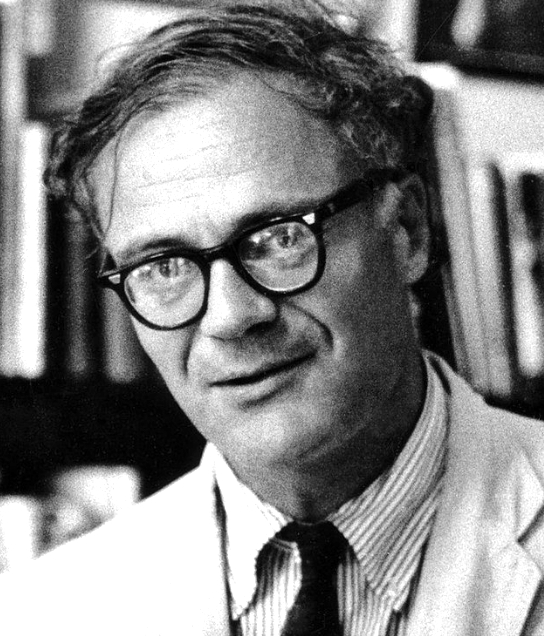

Robert Lowell

On this date in 1917, poet Robert Lowell, the great-grand nephew of James Russell Lowell, was born in Boston. At an early age, he knew he wanted to be a poet. As a 19-year-old, he wrote Ezra Pound a letter in which he confessed that Zeus and Achilles were “almost a religion” to him; how could the “insipid blackness of the Episcopalian Church” compete? (The New Yorker, March 20, 2017)

He attended Harvard for two years and eventually graduated from Kenyon College in 1940. He converted to Catholicism when he married novelist Jean Stafford. During World War II, he volunteered but was rejected due to poor vision. However, in 1943, he was drafted. Horrified by this time at the Allied bombing of civilians in Germany, Lowell became a conscientious objector, for which he was jailed as part of his sentence. He completed his first book, Land of Unlikeness, which was published as Lord Weary’s Castle in 1946 and received the 1947 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.

After divorcing (despite his conversion), Lowell married Elizabeth Hardwick, another writer, in 1949. The Mills of the Kavanaughs, Lowell’s next book, came out in 1951 to less acclaim. He suffered from manic depression in the 1950s, living much of the time in Europe. His career rebounded with Life Studies (1959), containing what one critic dubbed as “confessional” poetry.

Lowell became a Democratic activist in the 1960s, campaigning for Sen. Eugene McCarthy and against nuclear proliferation and the Vietnam War. His second marriage broke up and he married Caroline Blackwood in 1972. The Dolphin won the Pulitzer Prize in 1974. According to David Tribe in 100 Years of Freethought, Lowell became a freethinker. He translated the humanistic Prometheus Bound in 1969 (see quote below).

He died in 1977 at age 60 after suffering a heart attack in a cab in New York City on his way to see his ex-wife Elizabeth.

"[Prometheus to the chorus]: I have little faith now, but I still look for truth, some momentary crumbling foothold."

— Lowell translation of Aeschylus' "Prometheus Bound" (1969)

A.E. Housman

On this date in 1859, Alfred Edward Housman was born in England. He took a “passing degree” from Oxford, and received several university appointments, moving permanently to Trinity College in 1911. His most famous work, a book of poems called A Shropshire Lad, has stayed in print since it was first published in 1896. His second, long-awaited volume of poetry, Last Poems, was published in 1922.

After he died at age 77, his brother put together posthumous collections. Housman’s writing was irreverent: “It is a fearful thing to be The Pope. That cross will not be laid on me, I hope.”

In a letter to his devout Anglican sister Katharine six months before he died, he wrote: “I abandoned Christianity at thirteen but went on believing in God till I was twenty-one, and towards the end of that time I did a good deal of praying for certain persons and for myself. I cannot help being touched that you do it for me, and feeling rather remorseful, because it must be an expenditure of energy, and I cannot believe in its efficacy.” (“The Letters of A. E. Housman,” ed. Henry Maas, 1971) (D. 1936)

THE LAWS OF GOD, THE LAWS OF MAN

The laws of God, the laws of man,

He may keep that will and can.

Not I. Let God and man decree

Laws for themselves and not for me,

And if my ways are not as theirs

Let them mind their own affairs.Their deeds I judge and much condemn,

Yet when did I make laws for them?

Please yourselves, say I, and they

Need only look the other way.

But no, they will not. They must still

Wrest their neighbors to their will,

And make me dance as they desire

With jail and gallows and hell fire,

And how am I to face the odds

Of man's bedevilment and God's?I, a stranger and afraid

In a world I never made.

They will be masters, right or wrong.

Though both are foolish, both are strong.

And since, my soul, we cannot fly

To Saturn nor to Mercury,

Keep we must, if keep we can,

These foreign laws of God and men.— Housman verse included in "Poems of Irony and Wit" online, ed. Michael Dennis Mooney

Robert Frost

On this date in 1874, Robert Frost was born in San Francisco. His family relocated to New England when his father died. In 1892 he married Elinor White, with whom he was co-valedictorian at Lawrence High School. Although Frost later served as poet in residence and professor of literature at several universities, he never received a degree from Dartmouth or Harvard, both of which he attended.

The Frosts moved to England for a time, where he found success as a poet and was influenced by the work of Rupert Brooke, Robert Graves and Ezra Pound. The couple returned to New England, where his first two books of poetry were published to great acclaim in 1915, A Boy’s Will and North of Boston, followed by many other books of poetry.

Frost was awarded the Pulitzer Prize four times. He was sly about revealing his position on religion, telling freethought encyclopedist Warren Allen Smith that the answer was to be found in his work (see quotes). “Frost never made his beliefs clear, prompting biographers and others to theorize he was, among others, an atheist, a Unitarian, an agnostic and a follower of Swedenborgianism, his mother’s religion.” (University of Buffalo news release, Jan. 18, 2013.)

Jonathan Reichert, whose father was a Cincinnati rabbi who summered with Frost in Vermont, said Frost characterized himself as an “Old Testament Christian,” which Reichert interpreted to mean that Frost “saw that the laws that Judaism had built up really were not the essence, and that Jesus was a great prophet, rather than seeing Jesus as the son of God, or the savior.” (The New Antiquarian, Jan. 30, 2013.) D. 1963.

I turned to speak to God,

About the world's despair;

But to make bad matters worse,

I found God wasn't there.

God turned to speak to me

(Don't anybody laugh)

God found I wasn't there—

At least not over half.The kind of Unitarian

Who having by elimination got

From many gods to Three, and Three to One,

Thinks why not taper off to none at all.— Frost, "Not All There," Poetry magazine (April 1936); Frost, "A Masque of Mercy" (1947)

Algernon Charles Swinburne

On this date in 1837, poet Algernon Charles Swinburne was born in London into an Anglican High Church family. Very pious as a boy, he later used his familiarity with religion and the bible to pillory Christianity in countless poems, most famously in “Before a Crucifix” (1871), in which he has neither “tongue nor knee / For prayer.” In the poem he addresses a shrine as if it were Christ and questions if his coming has produced only a suffering race of men praying to a suffering image of man.

At Oxford he befriended the Pre-Raphaelite set. His poem “Atalanta in Calydon” (1865), which spoke of “the supreme evil, God,” helped launched his highly successful career. That was followed by “Poems and Ballads” (1866), the eroticism of which scandalized Victorian England but added to his poetic panache. He closely followed politics and was invited to represent English poetry in France at a commemoration of Voltaire‘s death in 1878.

Considered “excitable” as a youth and enjoying a reputation as a decadent, Swinburne was rescued from ill health, apparently caused by alcoholism, by legal adviser Theodore Watts. He lived his last 30 years at Watts’ home in great comfort. (D. 1909)

“Jowett, the great translator of Plato and a famous Broad Church liberal in religion, reputedly prevented Swinburne’s expulsion for atheism from Oxford with the statement that he did not want ‘Oxford to sin twice against poetry’ (the expulsion of Shelley being the first).”

— George P. Landow, Brown University professor of English and art history, The Victorian Web

Charles Baudelaire

On this date in 1821, influential poet Charles Pierre Baudelaire was born in Paris into an aristocratic, Catholic family. His father, a former priest, had, at age 60, married a 26-year-old woman. After Charles’ father died, his mother remarried, leading to an estrangement and what he recalled as a feeling of “eternal solitude” during his childhood. He abandoned religious notions in his youth. Educated at College de Lyon and Lycee Louis le Grand, he entered law school, where he apparently acquired both syphilis and an opium habit but no law degree.

Baudelaire was described as being “on the barricades” of the revolution of 1848. He translated Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales in 1856. His own collection of 151 short poems, Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil) came out in 1857, including the poem “Les litanies de Satan.” He, the publisher and the printer were all prosecuted for obscenity and blasphemy and found guilty. Six poems were excised to conform to the laws. He had several mistresses, primarily Jeanne Duval, a woman of mixed race whom he immortalized in his poem “Black Venus.”

Along with Mallarme and Verlaine, Baudelaire was one of the so-called “Decadents.” He had some success as a critic, and knew many writers and painters. His life ended in a medical downward spiral, but not before penning “Pauvre Belgique,” a collection of insults toward that country, where he had lived as an invalid, which has been published in several editions. Baudelaire died in his mother’s arms. (D. 1867)

"God is the only being who does not have to exist in order to reign."

— Baudelaire, quoted in "Who's Who in Hell" by Warren Allen Smith (2000)

Mark Strand

On this date in 1934, poet Mark Strand was born on Prince Edward Island, Canada. Strand was raised wary of religion, due to his atheist father who shared with him stories of heretics burned at the stake for their ideas. Strand was encouraged to pursue art by his mother, who was a painter. He attended Antioch College and Yale University, where he studied painting. After years of instruction, he realized that he was following the wrong career path and started studying 19th-century poetry. Soon after he received a master’s from the University of Iowa’s Writers’ Workshop.

Upon graduation, Strand taught at a number of universities, including Yale, Princeton and Harvard. He also held a position as Professor of Social Thought at the University of Chicago until 2005. Strand was the author of more than a dozen poetry books and several works of prose. His writings include “Sleeping With One Eye Open” (1964), “Reasons for Moving” (1968), “Darker” (1970), “The Story of Our Lives” (1973) and “Blizzard of One” (1999), which won a Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.

He died of liposarcoma at age 80 in Brooklyn, N.Y., when his daughter Jessica told The Guardian, “We weren’t religious people, but we worshipped at the foot of culture. He was always an artist.” (D. 2014)

"I haven't met God and I haven't been to heaven, so I'm skeptical. Nobody's come back to me to tell me they're having a great time in heaven and that they've seen God, although there are a lot of people claiming that God is telling them what to do. I have no idea how God talks to them. Maybe they're getting secret emails."

— Strand, quoted in his Associated Press obituary (Dec. 1, 2014)

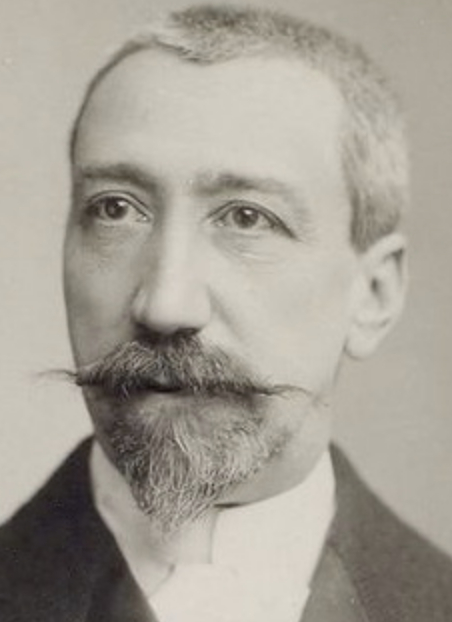

Anatole France

On this date in 1844, Anatole France (né François-Anatole Thibault) was born in Paris. A lifelong atheist, France was known for his anti-clericalism. France was a journalist, poet and writer whose breakthrough novel, The Crime of Sylvestre Bonnard (1881) centered around a skeptical scholar, perhaps modeled after the author himself. It was awarded a prize from the French Academy. France’s style, dry and ironic, was modeled in part on Voltaire and influenced by the French Enlightenment.

In 1905 he wrote a critical treatise, The Church and the Republic, which was instrumental in the campaign to disestablish the Catholic Church as the state religion. He served as an honorary president of the French National Association of Freethinkers. Penguin Island (1908) is France’s irreverent tale about a nearsighted abbot who baptizes penguins by mistake. In The Revolt of Angels (1914), France revisits Milton’s “Paradise Lost.” France depicted an angel leading a revolt after being influenced by the writings of Lucretius. With other writers, France came to the defense of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish captain falsely indicted for treason, and was a voice for reform.

His collection of aphorisms is called The Garden of Epicurus. France was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1921 “in recognition of his brilliant literary achievements, characterized as they are by a nobility of style, a profound human sympathy, grace, and a true Gallic temperament.” D. 1924.

"The thoughts of the gods are not more unchangeable than those of the men who interpret them. They advance — but they always lag behind the thoughts of men. … The Christian God was once a Jew. Now he is an anti-Semite."

— France letter to the Freethought Congress in Paris (1905), cited by Joseph McCabe in "Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists"

William Shakespeare

On this date in 1564, William Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England. The master playwright was eulogized by 19th-century agnostic orator Robert Green Ingersoll. In one of his famous lectures, Ingersoll said that when he read Shakespeare, “I beheld a new heaven and a new earth.” (The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, Interviews, Vol. IV) “Think of the different influence on men between reading Deuteronomy and ‘Hamlet’ and ‘King Lear.’ … The church teaches obedience. The man who reads Shakespeare has his intellectual horizon enlarged,” said Ingersoll in Vol. VIII.

No one knows Shakespeare’s personal religious views, although he certainly was not orthodox. He was born under the rule of Elizabeth I, who was Protestant and outlawed Catholicism, and was succeeded by James I, who continued Elizabeth’s policies despite his mother Mary Stuart’s Catholicism. Shakespeare’s parents were likely covert Catholics. His father John was close friends with William Catesby, father of the head conspirator in the Catholic “gunpowder plot” to blow the Protestant monarchy of James I to smithereens in November 1605.

Shakespeare put many different types of sentiments into the mouths of his characters. The bard’s philosophy seems most succinctly described in the famous “Seven Ages of Man” speech from “As You Like It,” which begins: “All the world’s a stage / And all the men and women merely players: / They have their exits and their entrances …” ending with “mere oblivion. / Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.”

In “King Lear,” the Duke of Gloucester laments in Act 4, Scene 1, “As flies to wanton boys, are we to the gods; they kill us for their sport.” Victorian poet, playwright and novelist Algernon Swinburne put it this way: “Shakespeare was in the genuine sense — that is, in the best and highest and widest meaning of the word, a Freethinker.” He died unexpectedly at age 52, cause unknown. (D. 1616)

"In religion, what damned error, but some sober brow will bless it and approve it with a text, hiding the grossness with fair ornament?"

— Bassanio in "The Merchant of Venice," Act III, Scene II (c. 1596-99)

Robert Browning

On this date in 1812, Robert Browning was born in London. The precocious child began writing poetry at age 12, attended London University College for a year at age 16 and eventually established his reputation as a major poet by 1845. One of his most famous writings is “The Pied Piper of Hamelin.” Although Browning’s mother was a devout evangelical, Robert announced at age 13 after reading “Queen Mab” by Shelley that he was (at least briefly) an atheist.

At a more mature age, Browning began reevaluating religion once more during his friendship with W.J. Fox, the former Unitarian minister at London’s famous South Place Chapel. “Who knows most, doubts most,” Browning wrote (cited in 2000 Years of Disbelief by James A. Haught).

Browning’s famous correspondence and whirlwind romance with poet Elizabeth Barrett resulted in their marriage in 1846. They settled in Italy for the benefit of Elizabeth, an invalid. They had a son, Robert (“Pen”) Jr., in 1849. At the death of his wife in 1861, Browning was said to have discarded any remaining Christian beliefs, although the degree of his skepticism is debated by academics. In The Ring and the Book, iv., Browning wrote: “Mothers, wives, and maids — There be the tools wherewith priests manage men.” (D. 1889)

"It is a lie — their Priests, their Pope,

Their Saints, their … all they fear or hope

Are lies, and lies — there! through my door

And ceiling, there! and walls and floor,

There, lies, they lie, shall still be hurled

Till spite of them I reach the world!”— Browning, "The Confessional" (1845)

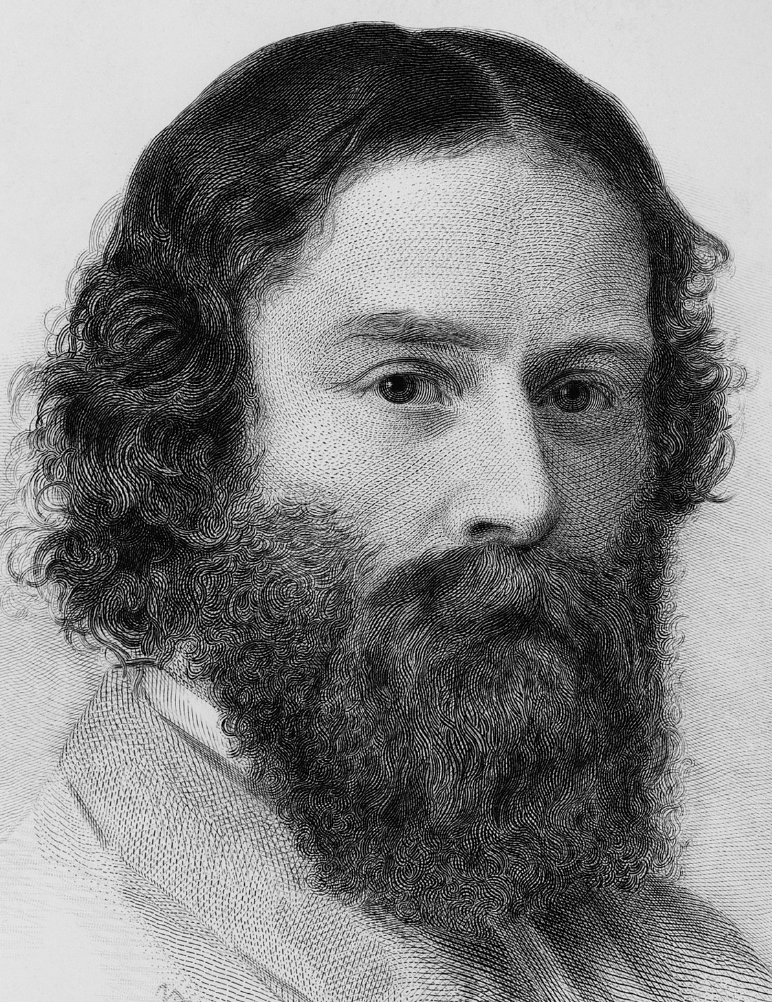

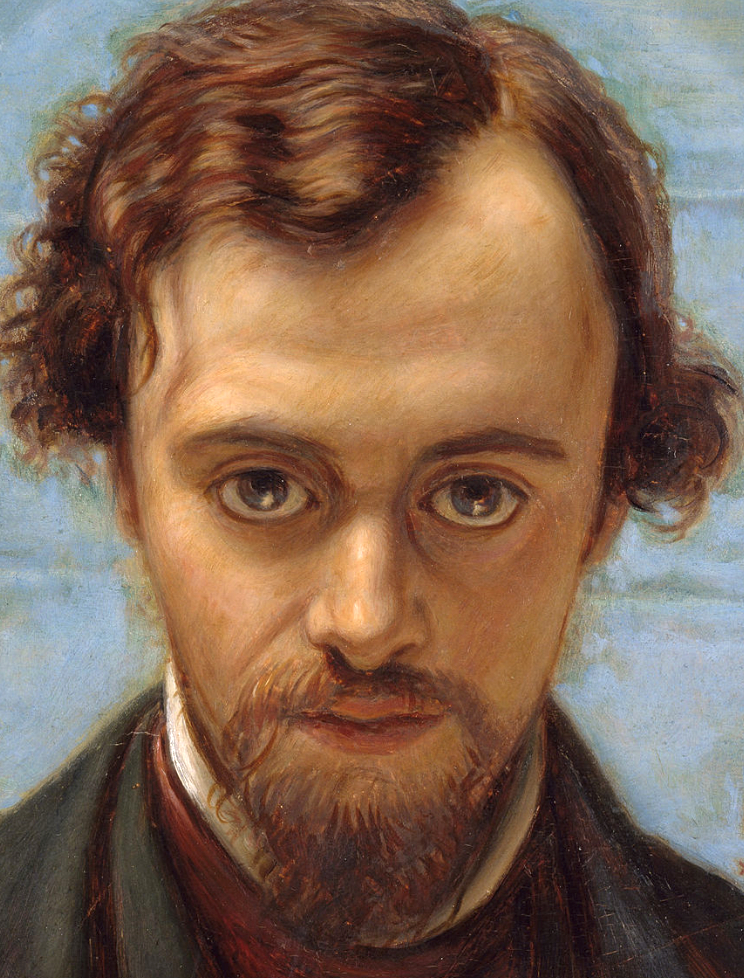

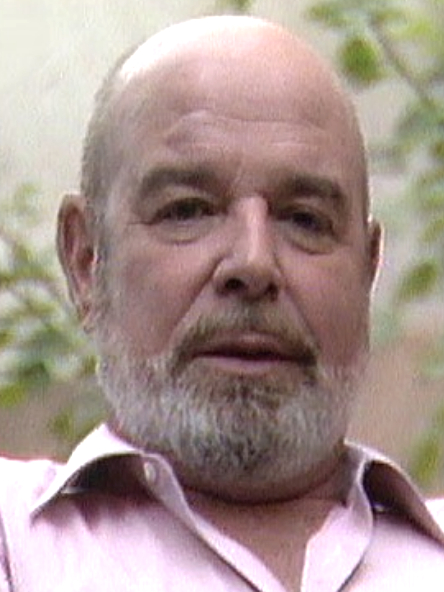

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

On this date in 1828, Dante Gabriel Rossetti was born in England, the son of an exiled Italian patriot. Educated at King’s College London and a drawing academy, Dante was both a well-known poet and painter, and became part of the Pre-Raphaelite movement (made up largely of freethinking artists). Rossetti’s sister was the poet Christina Rossetti. His early paintings, which were in oil and often with religious themes, were immediate hits, although some critics felt his poetry was his artistic forte.

Rossetti turned to watercolors and themes inspired by his namesake Dante Alighieri (whom Rossetti translated into English) and medieval themes in keeping with the Pre-Raphaelites. A favorite model was future wife Elizabeth Siddal, whose auburn hair and pure looks he immortalized. His sister Christina also posed for him. (Rossetti was played by Oliver Reed in Ken Russell’s 1967 television film “Dante’s Inferno.” Kelsey Grammer appeared in an episode of “Cheers” as Rossetti for his Halloween costume. His wife dressed as Christina.)

He married Siddall in 1860. So ill and frail from either tuberculosis or an intestinal disorder that she had to be carried to the wedding, two years later she was dead at age 32 of an overdose of laudanum she had become addicted to.

Wiliam Michael Rossetti, his brother, wrote in 1895: “He was never confirmed, professed no religious faith, and practised no regular religious observances; but he had … sufficient sympathy with the abstract ideas and the venerable forms of Christianity to go occasionally to an Anglican church — very occasionally, and only as the inclination ruled him.”

Rossetti died at age 53 of Bright’s disease (of the kidneys) after living for several years as a recluse due to ill health, increasing mental instability and addiction to chloral hydrate. (D. 1882)

PHOTO: Portrait of Rossetti at age 22 by William Holman Hunt.

“My brother was unquestionably sceptical as to many alleged facts, and he disregarded formulated dogmas, and the practices founded upon them. For theological discussions of whatsoever kind he had not the faintest taste, nor yet the least degree of aptitude.”

— "Dante Gabriel Rossetti: His Family-Letters with a Memoir, Vol. 1," ed. William Michael Rossetti (1895)

Alexander Pope

On this date in 1688, Alexander Pope was born in England. He was educated in Catholic schools. Pope contracted tuberculosis with the complication of Pott’s disease, or TB of the spine, giving him a hunchback and an adult height of 4 feet, 6 inches. Despite health problems, Pope was a published poet by his teens. He became his generation’s most-respected and popular poet, able to support himself with his writings. A deist and poet of the Enlightenment, his most famous couplet is “Know then thyself, presume not God to scan / The proper study of mankind is man.” (“Essay on Man,” 1733.)

“Essay on Man“ also contains the lines: “For modes of faith let graceless zealots fight / He can’t be wrong whose life is in the right.” Pope also wrote: “Slave to no sect, who takes no private road / But looks through Nature up to Nature’s God.”

Pope’s “Universal Prayer” (excerpt below) was likewise deistic. Pope contributed many immortal phrases, such as “damn with faint praise” (“Satires and Epistles, Prologue to Dr. Arbuthnot”), “a little learning is a dangerous thing” and “To err is human / to forgive divine” from “An Essay on Criticism.” (D. 1744)

“What conscience dictates to be done,

Or warns me not to do,

This teach me more than Hell to shun,

That more than Heaven pursue.”— Pope, "Universal Prayer" (1738)

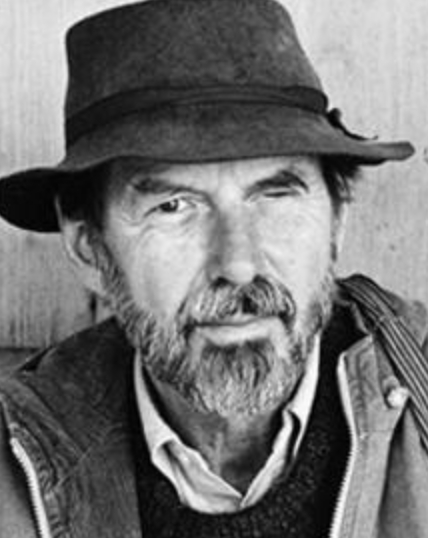

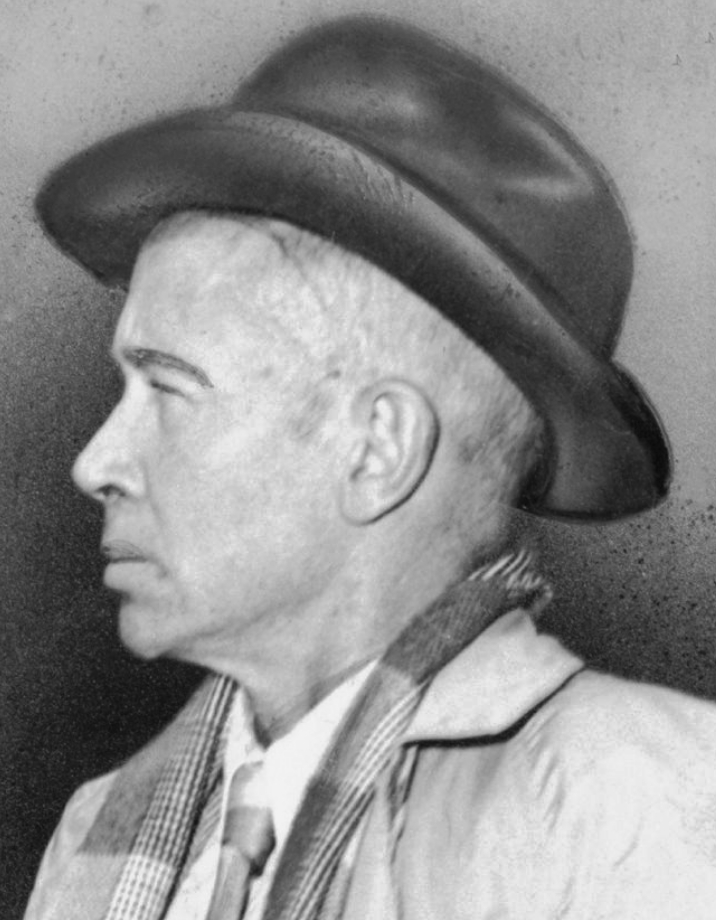

Robert Creeley

On this date in 1926, poet Robert White Creeley was born in Arlington, Mass. His physician father died when Creeley was 4; earlier he had lost his left eye in a car accident. He attended Harvard University from 1943-46 but took time off to serve in the American Field Service as an ambulance driver in Burma and India during World War II.

Creeley returned to Harvard after the war but didn’t graduate. He later received a B.A. from North Carolina’s Black Mountain College and an M.A. from the University of New Mexico. During the 1950s, he taught at Black Mountain (an experimental college that operated from 1933-57) and edited the Black Mountain Review, still recognized as a significant, experimental “little magazine.”

Creeley published over 60 books of poetry, one novel and more than a dozen works of prose, essays and interviews. According to the Poetry Foundation, he transformed American poetry “by being more conversational and emotionally direct” and is credited with formulating the concept that “form is never more than an extension of content.” He taught English and poetics at the State University of New York in Buffalo for over 30 years and lectured academically on poetry at schools around the world.

He married Ann MacKinnon while at Harvard, and in the late 1940s they lived in New Hampshire before moving to France and then the island of Mallorca, where they founded the short-lived Divers Press. Creeley left Black Mountain in 1956 and immersed himself in the poetry renaissance in San Francisco with Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Kenneth Rexroth and others, while befriending Jack Kerouac.

After divorcing, he moved to New Mexico, where he taught and married Bobbie Louise Hawkins before filling his professorial chair at SUNY-Buffalo. They divorced in 1976 and the next year Creeley married Penelope Highton, a New Zealander. He also served as New York state poet laureate from 1989-91 and was elected a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets in 1999. He died at age 78 of complications of pneumonia while living with Penelope in Marfa, Texas. He had seven children and one stepchild. The Robert Creeley Foundation honors his legacy. (D. 2005)

“I believe in a poetry determined by the language of which it is made. … I look to words, and nothing else, for my own redemption.”

— From Creeley's essay "A Note," Nomad magazine (Winter-Spring 1960)

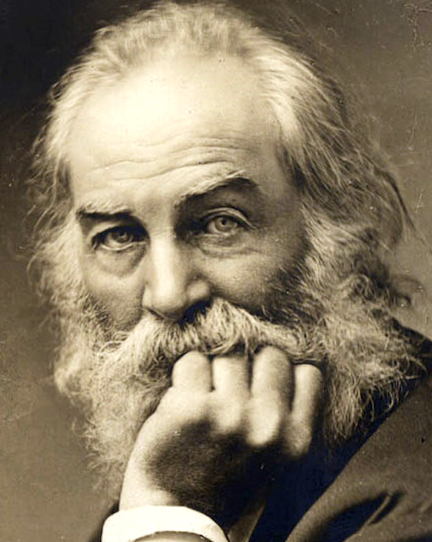

Walt Whitman

On this date in 1819, Walter Whitman was born on Long Island, N.Y., the second of nine children born to Louisa (Van Velsor) and Walter Whitman, who had Quaker ties. After working as a clerk, teacher, journalist and laborer, Whitman wrote his masterpiece, Leaves of Grass, pioneering free-verse poetry in a humanistic celebration of humanity, in 1855. Emerson, whom Whitman revered, said of Leaves of Grass that it held “incomparable things incomparably said.”

During the Civil War, Whitman worked as an army nurse, later writing Drum Taps (1865) and Memoranda During the War (1867). His health was compromised by the experience and he was given work at the Treasury Department in Washington. After a stroke in 1873, which left him partially paralyzed, Whitman lived with his brother, writing mainly prose, such as Democratic Vistas (1870).

Leaves of Grass was published in nine editions, with Whitman elaborating on it in each successive edition. In the preface of the 1855 edition, Whitman wrote, “This is what you shall do: Love the earth and sun and animals, despise riches, give alms to everyone that asks, stand up for the stupid and crazy, devote your income and labor to others, hate tyrants, argue not concerning God.” In 1881, the book had the compliment of being banned by the commonwealth of Massachusetts on charges of immorality.

Whitman was influenced by deism and was a religious skeptic. Invited in 1874 to write a poem about the Spiritualism movement, he responded, “It seems to me nearly altogether a poor, cheap, crude humbug.” (“Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself” by Jerome Loving, 1999) Biographers continue to debate Whitman’s sexuality, and he is usually described as either homosexual or bisexual in his feelings and attractions.

He died at 72 of pleurisy and tuberculosis in Camden, N.J. Robert Ingersoll delivered the public eulogy at the cemetery. (D. 1892)

"I think I could turn and live with animals, they’re so placid and self-contain’d,

I stand and look at them long and long.

They do not sweat and whine about their condition,

They do not lie awake in the dark and weep for their sins,

They do not make me sick discussing their duty to God.”— Whitman, "Leaves of Grass" (1891 edition)

Maxine Kumin

On this date in 1925, writer and poet Maxine Kumin was born in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia to a Jewish immigrant family. Kumin was the only daughter and youngest of four children. Before attending secular Philadelphia schools, she was enrolled at a Catholic school run by the Sisters of St. Joseph. In 1946 she received a B.A. from Radcliffe College in history and literature. After graduation she married Victor Montwid Kumin and they had three children together. Kumin returned to Radcliffe in 1948 to pursue her master’s and took a workshop nearby at the Boston Center for Adult Education conducted by John Holmes. This workshop contributed to Kumin’s career development as a poet.

After much patience as a closet poet, her first book of poetry, Halfway, was published in 1961. She published 13 more poetry books, along with numerous children’s books and other novels. “Mother Rosarine,” “The Spell,” “The Pawnbroker” and “The Chain” are some of her poems that are reflective of her Jewish heritage. Two of her other poems, “Living Alone with Jesus” and “For A Young Nun at Breadloaf,” allowed Kumin to show how religious and cultural differences can be bridged in the realm of imagination. An atheist since she was a teen, Kumin said she sometimes used God as a rhetorical device in her poetry.

Some of her later works included Our Ground Time Here Will Be Brief (1982), Looking for Luck (1992) and Connecting the Dots (1996). Kumin won a Pulitzer Prize in 1973, the Aiken Taylor Award for Modern American Poetry in 1995 and the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize in 1999. She was also elected a chancellor in the Academy of American Poets before she resigned in 1998 in protest of the lack of blacks and other minorities on the board. Kumin enjoyed being reclusive on her farm in New Hampshire, which became her safe haven after she and her husband discovered the abandoned farm in 1962. (D. 2014)

"I don’t see any wavering between agnosticism and atheism. I’ve been an atheist since the age of about 16."

— "An interview with Maxine Kumin," World Poetry Inc. (2010)

Ignacio Ramírez

On this date in 1818, poet, lawyer and journalist Juan Ignacio Paulino Ramírez Calzada was born in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. Known by the pen name “El Nigromante” (The Necromancer), Ramírez co-founded Don Simplicio, a satirical periodical, with politician and journalist Guillermo Prieto. Ramírez, an advocate for educational and economic reforms as well as women’s rights, said that “education is the only possible way to achieve well-being.” (“Ignacio Ramírez,” Jardón.)

He was exiled to California during the reign of Emperor Maximillian. Upon his return to Mexico he was appointed to the Supreme Court. During his time as minister of justice and education, he expanded public education and established secondary education, especially for women and indigenous people.

A lifelong champion of atheism and freethinking, Ramírez caused a scandal when, in a speech to the literary Academy of San Juan de Letrán, he declared God didn’t exist (see quote). Despite the controversy, he was accepted into the academy. Even after his death, his atheism was controversial.

In 1948, artist Diego Rivera painted a mural wherein Ramírez is depicted holding a sign saying “Dios no existe” (God does not exist). Rivera would not remove the inscription so the mural was not shown for nine years until after Rivera agreed to remove the offending words. (D. 1879)

"No hay Dios; los seres de la naturaleza se sostienen por sí mismos." ("There is no God. Natural beings sustain themselves.")

— Ramírez's entry by María Elena Victoria Jardón in "The Encyclopedia of Mexico" (1997)

Alexander Pushkin

On this date in 1799, Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin was born in Moscow. Born into a poor, aristocratic family, Pushkin saw his first poem published at age 14. He joined the foreign office in 1817 but was banished to South Russia as a young man for radical poetry that also satirized religion, such as “Ode to Liberty.” He was permitted to return to his mother’s estate and then to St. Peterburg after several years.

Pushkin’s epics include “Ruslan and Ludmila” (1820), “Boris Gudenov” (1831), and “Evgenii Onegin” (1833). He returned to a government position in 1831, and founded a review publication in 1836. He died of peritonitis after fighting a duel over his young wife in 1837. Pushkin’s complete works were published in 12 volumes. An admirer of the Enlightenment and Voltaire, the deistic writer is considered the founder of modern Russian literature. (D. 1837)

Sherry Matulis

On this date in 1931, Sherry Matulis was “born an atheist (aren’t we all?),” she mused, in the small town of Nevada, Iowa. “You couldn’t go out to play hopscotch or kick-the-can without tripping over a church or two. (Or a tavern. The churches had a reciprocal arrangement, I think),” she wrote in a column for The Feminist Connection. “But tripping over all those churches wasn’t the real problem. The real problem was all that time spent inside them — skipping over the facts of reality.” (Oct. 24, 1981, speech to the FFRF national convention in Louisville, Ky.)

At age 20 she was surprised to find herself in the first Miss Universe contest, selected by photographs submitted by her husband. As the “village atheist” in Peoria, Ill., Matulis ran small businesses for many years and had five children. A poet and writer, she became a national spokesperson for abortion rights in the 1980s, when she wrote about her life-threatening experience in seeking an illegal abortion in Peoria in 1954. She was invited to speak about her experiences before a U.S. Senate subcommittee chaired by Orrin Hatch in 1981 and testified before several state legislatures.

A firm atheist, she appeared on many radio and national TV programs. Her articles, stories and poetry have been published in such periodicals as Redbook, Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, Questar, Analog, Freethought Today and The Rationalist. She received many awards for her work to protect abortion rights, including from the American Humanist Association and the National Organization for Women. (D. 2014)

Religion’s Child

Aware of light and yet condemned to grope

Through dark regression’s cave, told she must find

Life’s purpose in that blackness, without hope,

Denied the luminescence of her mind

Until, at last, she finds the darkness kind,

Religion’s child — a babe once bright and fair,

Curls up, tucks in her tail, and says her prayer.— Matulis, "Women Without Superstition," ed. Annie Laurie Gaylor (1997)

Pablo Neruda

On this date in 1904, Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto was born in Parral, Chile. His first poems were published under the pen name Pablo Neruda in 1918 in a Santiago magazine. His first widely read book, Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair was published in 1924. In 1927 he was made Chilean honorary consul to Rangoon, Burma (now Myanmar), in honor of his accomplishments in poetry.

His work as an official representative of Chile continued in Spain, where he became involved with the republican cause. He was recalled to Chile in 1937. In 1945 he joined the Communist Party and was elected to the Senate, fleeing the country three years later when the party was banned by the government.

Neruda continued to travel the world, first in exile and after he was allowed to return to Chile in 1952. During this period, much of his poetry was political in nature, including the famous “Canto General” (General Song), an epic of the New World, which connected the Americas’ origins and conquests to their current political state.

Neruda was a confirmed communist and was awarded the Stalin Peace Prize and Lenin Peace Prize in 1953. He stated some philosophical views in his poetry, describing himself in his poem “A Dog Has Died” as “I, the materialist, who never believed / in any promised heaven in the sky / for any human being.” He ran for president of Chile in 1969 but withdrew in favor of Salvador Allende. He was diagnosed with cancer in 1970 but went on to represent Chile as ambassador to France.

In 1971 he received the Nobel Prize in Literature. He survived Allende by only 12 days. Eight books of his poetry, which he had planned on publishing on his 70th birthday, were published posthumously. (D. 1973)

“Like his father, Neruda was an atheist, and he felt an intuitive aversion to the mystical religions of Asia, which was later confirmed by his embrace of Communism, with its doctrinaire rejection of all religion.”

— Jamie James, "Pablo Neruda's Life as a Struggling Poet in Sri Lanka," Literary Hub (June 3, 2019)

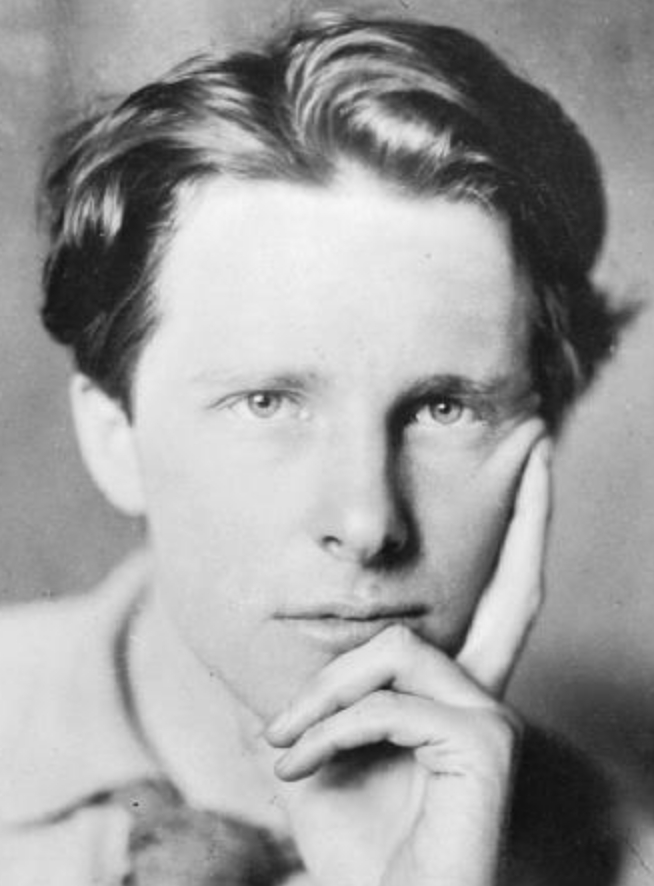

Rupert Brooke

On this date in 1887, Rupert Brooke was born in England. The Cambridge-educated poet became a celebrity among his Fabian Society peers. W.B. Yeats famously dubbed him “the handsomest young man in England.” Bertrand Russell, in his autobiography, recorded there was “no humbug” in Brooke. He traveled widely, including trips to North America and the South Seas. He edited an anthology of Georgian poetry and his own book, Poems 1911, came out the same year.

When World War I broke out in 1914, the 27-year-old became a sub-lieutenant in the Royal Navy. Weakened by a series of illnesses, Brooke died off the Greek island of Skyros of blood poisoning from an insect bite. He had only seen combat once, but his sonnet, “Soldier” and several other wartime poems, became celebrated during the early, war-fevered years. Winston Churchill wrote a patriotic obituary after his death. Brooke was at minimum a strong doubter. Below is an excerpt of his poem “Heaven.” Click here for an animated musical version by FFRF’s Kati Treu and Dan Barker. ( D. 1915)

Fish say, they have their Stream and Pond;

But is there anything Beyond?

This life cannot be All, they swear,

For how unpleasant, if it were!

One may not doubt that, somehow, Good

Shall come of Water and of Mud;

And, sure, the reverent eye must see

A Purpose in Liquidity.

We darkly know, by Faith we cry,

The future is not Wholly Dry.

Mud unto mud! — Death eddies near —

Not here the appointed End, not here!

But somewhere, beyond Space and Time.

Is wetter water, slimier slime!

And there (they trust) there swimmeth One

Who swam ere rivers were begun,

Immense, of fishy form and mind,

Squamous, omnipotent, and kind;

And under that Almighty Fin,

The littlest fish may enter in.— Rupert Brooke, "Heaven" (1913)

Percy Bysshe Shelley

On this date in 1792, Percy Bysshe Shelley, one of atheism’s most passionate advocates, was born in Field Place, Sussex, England. As an 18-year-old, Shelley was expelled from Oxford University for writing The Necessity of Atheism (1811), a pamphlet which opens: “There is no God.” Shelley vigorously protested the imprisonment of an elderly publisher for distributing Thomas Paine‘s Age of Reason in another pamphlet, “A Letter to Lord Ellenborough.” Shelley’s Declaration of Rights further championed freedom of thought and press.

In A Refutation of Deism (1814), Shelley averred, “It is among men of genius and science that atheism alone is found.” Freethought permeated his other writings, including Hymn to Intellectual Beauty (1816), The Revolt of Islam (1817), Peter Bell the Third (1819) and Ode to Liberty (1820). When he eloped with 16-year-old Harriet Westbrook, the daughter of a barkeeper, his father disinherited him. The pair briefly went on a political speaking tour in Ireland. They had two children but the marriage was unsuccessful despite Shelley’s increasing recognition as a poet.

New scandal followed when he ran off with 16-year-old Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, the daughter of atheist writer William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft. The young couple fled to the continent, traveling for a time with Lord Byron. During a writing race between the trio, Mary produced her famous classic Frankenstein. When Shelley’s first wife committed suicide, he was denied custody of their two sons because of his infidel views. Mary Godwin and Percy wed in 1816, and had a son William.

The young couple moved to Italy, where Shelley penned Prometheus Unbound, a lyrical drama. Shelley, at Byron’s invitation, sailed to Pisa to consult over a new magazine. Shelley drowned tragically at 29, along with two others, on the return trip when their yacht capsized in a storm. (D. 1822)

"If ignorance of nature gave birth to gods, knowledge of nature is made for their destruction."

— Percy Bysshe Shelley, "The Necessity of Atheism" (1811)

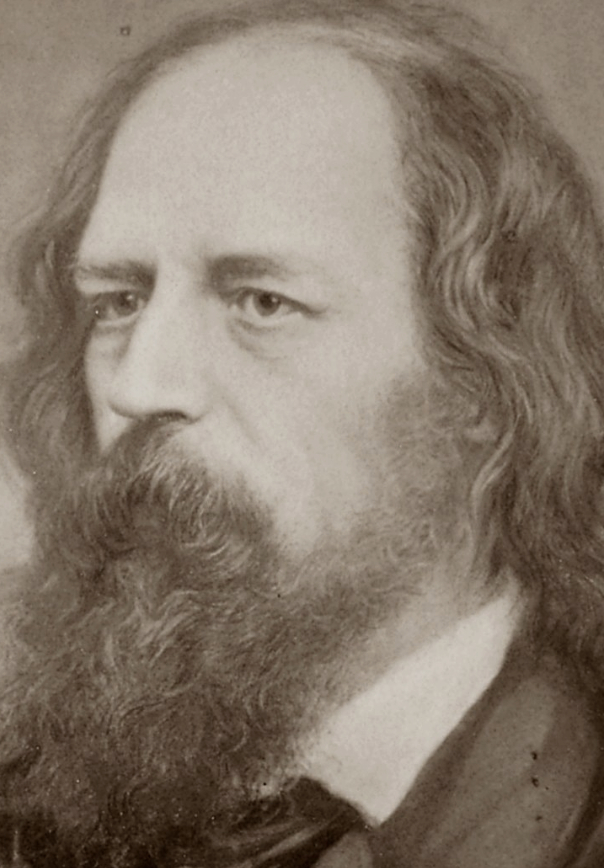

Alfred, Lord Tennyson

On this date* in 1809, Alfred Tennyson was born in England. By the time his volume of Poems was published in 1833 (including “The Lady of Shalott”), Tennyson had established his literary acumen. By 1850 he had earned the title of poet laureate. Tennyson, a deistic pantheist, was not entirely unorthodox but he routinely trumpeted freedom. He alienated freethinkers of his day when he wrote an agnostic hero in Promise of May (1882) was an “unworthy character.”

Tennyson made up for such an undiplomatic lapse in other writings. In “In Memoriam A.H.H.” (1849), he famously wrote, “There lives more faith in honest doubt, believe me, than in half the creeds.” In “Maud” (1855) he wrote, “The churches have killed their Christ.” In “Locksley Hall Sixty Years After,” Tennyson wrote, “Christian love among the churches look’d the twin of heathen hate.”

Tennyson married the poet Emily Sellwood, a friend since childhood, in 1850. They had two sons, Hallam, born in 1852, and Lionel, born in 1854. Queen Victoria named Alfred the Baron Tennyson in 1884 and he took his seat in the House of Lords.

Tennyson recorded in his “Diary” (p. 127): “I believe in Pantheism of a sort.” His son’s biography confirms that Tennyson was not Christian, noting that Tennyson praised Giordano Bruno and Spinoza on his deathbed, saying of Bruno: “His view of God is in some ways mine.” (D. 1892)

* Tennyson’s birthdate is given as Aug. 5 by some sources. According to one, his baptismal records said Aug. 5 but his mother preferred to celebrate his birthday on the 6th, her wedding anniversary.

“It is inconceivable that the whole universe was merely created for us who live in this third-rate planet of a third-rate sun.”

— Tennyson, quoted in "Alfred Lord Tennyson: A Memoir, Vol. 1" by Hallam Tennyson (1897)

Taslima Nasrin

On this date in 1962, freethinker, atheist and feminist Taslima Nasrin was born in Mymensing, Bangladesh, to a Sufi physician and a devoutly religious mother. Nasrin later became the target of a series of fatwas, or religious sanctions, condemning her to death for blasphemy.

“I came to suspect that the Quran was not written by Allah but, rather, by some selfish, greedy man who wanted only his own comfort,” Nasrin explained in her speech accepting a Freethought Heroine Award at the 25th annual FFRF convention in 2002. “So I stopped believing in Islam. When I studied other religions, I found they, too, oppressed women.” She has often stated, “Religion is the great oppressor, and should be abolished.”

Nasrin earned an MBBS degree in 1984 and worked in gynecology and anesthesiology departments in medical colleges and universities. Her books of poetry began being published in the late 1980s, then she started writing popular columns on women’s rights in newspapers and magazines, which were collected in book form. In 1992, she received the prestigious Indian literary award “Ananda” for her book of essays. Nasrin reports that Islamic fundamentalists started campaigns against her by 1990, with demonstrations escalating over the next few years, including having her books burned at the national book fair.

When the novella “Shame” came out in 1993, about the plight of Hindus under Muslim order, it was banned, she was attacked at the national book fair, the first of three fatwa was issued, and a bounty on her head was offered. The Bangladeshi government brought criminal charges against her for defaming the Muslim faith the following year. Thousands in Bangladesh demonstrated regularly, sometimes daily, demanding her death. After a terrifying two months in hiding, and fearing the fate of Hypatia, Nasrin fled Bangladesh, seeking refuge in Sweden.

In a 1994 interview with The New Yorker, she said, “I want a modern, civilized law where women are given equal rights. I want no religious law that discriminates, none, period — no Hindu law, no Christian law, no Islamic law. Why should a man be entitled to have four wives? Why should a son get two-thirds of his parents’ property when a daughter can inherit only a third?”

Nasrin, a “woman without a country,” has also lived in France, the U.S. and Germany, living, for the most part, in India.

Among the dozens of awards and honorary doctorates she has received is the Sakharov Prize (1994). In addition to receiving FFRF’s 2002 Freethought Heroine Award, she was the recipient in 2015 of its Emperor Has No Clothes Award and said, “Islam is not compatible with human rights, women’s rights, freedom of expression and democracy.” She has continued to lecture, speak out and write, including a multi-book autobiography.

PHOTO: Nasrin at FFRF’s national convention in 2015; Ingrid Laas photo.

“There has always been a marked conflict between religion and science, and every time science emerges as the winner, as science bases itself on facts, not faith. It supports what is tested and is true and truth cannot be hidden by lies for a very long time. To abolish all kinds of hypocrisy from my country, we need more atheists to speak the truth.”

— Nasrin, accepting the Emperor Has No Clothes award in 2015

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

On this date in 1749, Germany’s most famous poet, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, was born in Frankfurt am Main, to a comfortable bourgeois family. He began studying law at Leipzig University at the age of 16 and practiced law briefly before devoting most of his life to writing poetry, plays and novels. In 1773, Goethe wrote the powerful poem “Prometheus,” which urged human beings to believe in themselves more than in gods.

His first novel was The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774), a semi-autobiographical tragedy about a doomed love affair. A line from that novel: “We are so constituted that we believe the most incredible things: and, once they are engraved upon the memory, woe to him who would endeavor to erase them.” In his 1797 Hermann and Dorothea, Goethe observed: “The happy do not believe in miracles.” Goethe typified the Sturm und Drang romantic movement, celebrating the individual. The Grand Duke of Weimar appointed him an administrator in 1775, where, according to some historians, Goethe turned Weimar into “the Athens of Germany.”

Goethe was keenly interested in the natural sciences and in his studies discovered the human intermaxillary bone (also known as the Goethe bone, adjacent to the incisors). After a sojourn in Italy from 1786 to 1788 he returned to his art, starting a journal inspired by Christopher Marlowe‘s play “Faust,” Goethe wrote part 1 of his most famous play, published in 1808. Part 2 was published in 1832. From Part 1, Scene 9: “The church alone beyond all question / Has for ill-gotten gains the right digestion.”

Goethe’s religious beliefs were complicated and changed at various periods in his long life. He was raised Lutheran and was quite devout when young but grew to have problems with Christianity’s dogma, hierarchy and superstitious aspects. He revered Spinoza, whom Nietzsche often paired with Goethe. His later spiritual perspective incorporated pantheism (heavily influenced by Spinoza), humanism and elements of Western esotericism, as seen most vividly in part 2 of “Faust.”

“Goethe was a freethinker who believed that one could be inwardly Christian without following any of the Christian churches, many of whose central teachings he firmly opposed, sharply distinguishing between Christ and the tenets of Christian theology, and criticizing its history as a ‘mishmash of fallacy and violence,’ ” states the 1982 German publication Goethe’s Poems in Chronological Order.

He died at age 82 of apparent heart failure in Weimar. Of his five children, only a son, August, survived into adulthood. (D. 1832)

In the wilderness a holy man

To his surprise met a servant of Pan,

A goat-footed faun, who spoke with grace;

“Lord, pray for me and for my race,

That we in heaven find a place:

We thirst for God’s eternal bliss.”

The holy man made answer to this:

“How can I grant thy bold petition,

For thou canst hardly gain admission

In heaven yonder where angels salute:

For lo! thou hast a cloven foot.”

Undaunted the wild man made the plea

“Why should my hoof offensive be?

I’ve seen great numbers that went straight