playwrights

Molière

On this date in 1622, playwright and poet Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, who adopted the stage name Molière as an actor, was born in Paris. His father was an upholsterer/valet to King Louis XIII. Molière studied philosophy in college, started a Parisian acting troupe and toured the provinces with it for many years, acting, directing and writing.

As a favorite of King Louis XIV, he produced a succession of 12 popular comedies still being performed, including “The School for Wives” (1662), “Don Juan” (1665), “Le Misanthrope” (1666) and “Tartuffe” (1667), all irreverent and increasingly irreligious. “Tartuffe,” a satire on religiosity, originally featured a hypocritical priest. Although Molière rewrote Tartuffe’s profession to avoid scandal, some religious officials nevertheless called for him to be burned alive as punishment for his impiety. He would claim he was attacking hypocrisy more than religion.

He married actress Armande Bejart when she was 19 and they had a daughter, Esprit-Madeleine, in 1665. Becoming ill while playing the lead in his play “Le Malade imaginaire” (“The Imaginary Invalid”), Molière insisted on finishing the show, after which he died. He had long suffered from tuberculosis. The church refused to bury him in sanctified ground because he had not received the last rites and did not renounce his profession as an actor before his death. When the king intervened, the archbishop of Paris allowed him to be buried only after sunset among the suicides’ and paupers’ graves with no requiem Masses permitted in the church. (D. 1673)

“Though living in an age of reason, he had the good sense not to proselytize but rather to animate the absurd …”

— Encyclopedia Britannica entry on Molière

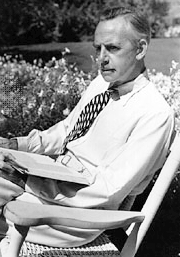

A.A. Milne

On this date in 1882, classic children’s author Alan Alexander Milne, known as A.A. Milne, was born in England and brought up in London. With his brothers he attended his schoolteacher father’s school, Henley House. One of his influential teachers there was H.G. Wells. Attending Cambridge on a mathematics scholarship, Milne was given the gift of 1,000 pounds by his father upon graduation. He used it to move back to London and become a writer.

Milne freelanced for newspapers, joined the staff of Punch magazine and wrote a book that flopped, Lovers in London. In 1913 he married Dorothy “Daphne” de Sélincourt. In 1915 he volunteered in World War I and wrote his first play while serving. His only child, Christopher Robin, was born in 1920. In his 1974 book The Enchanted Places, Christopher wrote about being estranged from his parents and resenting what he came to see as his father’s exploitation of his childhood.

In his obituary in 1996, The Observer wrote: “Christopher Robin, a ‘sweet and decent’ man who overcame a childhood in which he was haunted by Pooh and taunted by peers, has left without saying his prayers – he was a dedicated atheist – aged 75.”

Milne’s When We Were Young was published in 1924, followed by Winnie the Pooh (1926), The House at Pooh Corner (1926) and Now We Are Six (1927). Milne subsequently wrote several plays, a detective novel and, in 1952, Year In, Year Out. (D. 1956)

PHOTO: Milne and Christopher Robin in 1926.

"The Old Testament is responsible for more atheism, agnosticism, disbelief — call it what you will — than any book ever written; it has emptied more churches than all the counter-attractions of cinema, motor bicycle and golf course."

— A.A. Milne, cited in "2000 Years of Disbelief" by James A. Haught (1996)

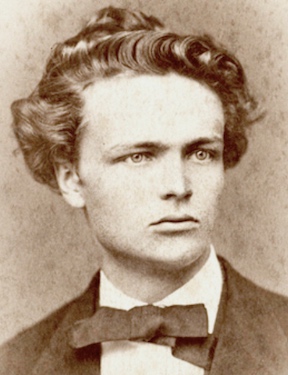

Johan August Strindberg

On this date in 1849, dramatist and novelist Johan August Strindberg, one of nine children, was born in Stockholm, Sweden. His family was poor, as demonstrated by the title of his autobiography, The Son of a Servant (1886). He attended Upsala University and, while working at the Royal Library in Stockholm, wrote a popular novel, Roda rummet (1879), which made him a national celebrity. The author of more than 70 plays, he is considered an important influence to modern playwrights.

His 1882 religious satiric story, Det nya riket (The New Kingdom), created such a ruckus he had to leave the country. When he returned he became an active leader with the Swedish Rationalists. He corresponded with Nietzsche and was an admirer of Edgar Allan Poe. A passage with an unorthodox description of the Last Supper in his collection of his stories, Giftas (1884), was censored as anti-Christian and Strindberg was charged with blasphemy.

Although in Switzerland at the time, he returned to Sweden to face charges and was acquitted. He suffered a mental breakdown, which he never really recovered from, in the late 1890s, although he remained active in theater. (D. 1912)

PHOTO: Strindberg at age 25.

"Reason, too, was sin; the greatest of all sins, for it questioned God's very existence, tried to understand what was not meant to be understood. Why it was not meant to be understood was not explained; probably it was because if it had been understood the fraud would have been discovered."

— Strindberg, "Married" ("Giftas"), 1884

Christopher Marlowe

On this date in 1564, Christopher “Kit” Marlowe was born. The poet and dramatist, who authored “Tamburlaine” (c. 1587) and “Tragedy of Dr. Faustus” (c. 1588), was a contemporary of William Shakespeare. Educated at Cambridge, Marlowe worked as an actor and dramatist. One of his enduring poems is the “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love” with its opening line “Come live with me and be my love.”

Marlowe, with Sir Walter Raleigh and others, established the first Rationalist group in English history, according to freethought historian Joseph McCabe. Marlowe was derided as an “atheist” by several contemporary political enemies. His character Faustus concludes “hell’s a fable,” and his villain-hero Tamburlaine burns the Quran and challenges Muhammad to “work a miracle.” The Privy Council had decided to prosecute Marlowe for heresy, accusing him of writing a document denying the divinity of Christ, a few weeks before his death in a barroom brawl. There has been endless speculation over Marlowe’s short life and violent death at age 29. (D. 1593)

"[H]e counts religion but a childish toy,

And holds there is no sin but ignorance."— Marlowe, "The Jew of Malta" (c. 1589)

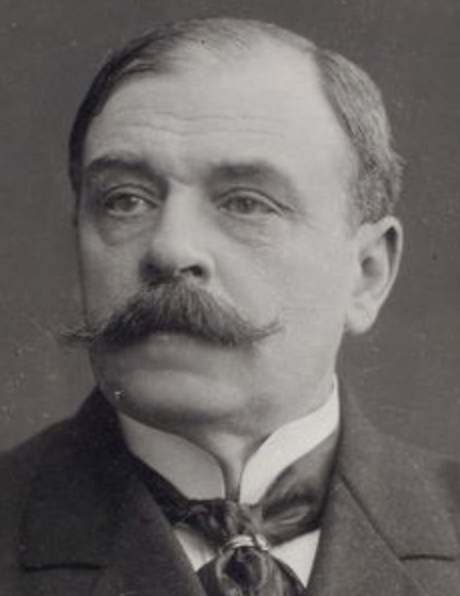

Octave Mirbeau

On this date in 1848, French playwright and novelist Octave Mirbeau was born in Paris. He was expelled from a Jesuit college at age 15. Mirbeau adopted strong anarchist views and a fondness for art and art criticism. He ghost-wrote at least 10 novels and many under his own name, including Le Calvaire (Calvary, 1886), Le Journal d’une femme de chambre (Diary of a Chambermaid, 1900) and Dingo (1913). In his 1888 novel, L’Abbé Jules, Mirbeau’s main character is a priest who rebels against Catholicism. The novel explores the repressive and abusive role religion plays in human life.

Sébastien Roch, published in 1890, recounts the sexual abuse of a 13-year-old boy by priests that results in the boy’s expulsion from school and the subsequent destruction of his life. Mirbeau’s plays included “Les Mauvais bergers” (The Bad Shepherds, 1897), the acclaimed “Les affaires sont les affaires” (Business is Business, 1904) and “Le Foyer” (Charity, 1908), a comedy accusing the Catholic Church of exploiting young girls. Mirbeau and French actress Alice Regnault wed in London in 1887. Mirbeau is buried in Paris. D. 1917.

"The universe appears to me like an immense, inexorable torture-garden. … Passions, greed, hatred, and lies; social institutions, justice, love, glory, heroism, and religion: these are its monstrous flowers and its hideous instruments of eternal human suffering."

— from Mirbeau's novel "Le Jardin des supplices" (The Torture Garden), 1899

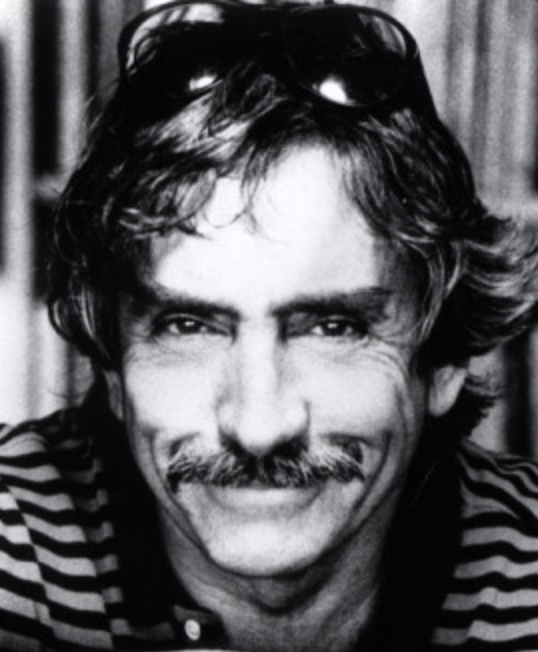

Edward Albee

On this date in 1928, playwright Edward Franklin Albee III was born to Louise Harvey in the District of Columbia and grew up in Larchmont, N.Y., after being given up for adoption when he was 18 days old. His adoptive family was prosperous and owned a chain of theaters. A rebellious teen growing up in a conservative household, Albee was expelled from Trinity College in Hartford, Conn., because he failed to attend chapel and classes.

At 20 he moved to New York’s Greenwich Village, where he took odd jobs, such as being a messenger for Western Union, while writing. His first breakthrough play “The Zoo Story” (1959), belonging to the theater of the absurd, was originally produced in Germany.

Albee was awarded three Pulitzer Prizes for his plays “A Delicate Balance” (1966), “Seascape” (1975) and “Three Tall Women” (1994). He won the 1963 Tony Award for Best Play for “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” It opened on Broadway with Uta Hagen and Arthur Hill as Martha and George and was adapted for the 1966 film starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. He won a second Best Play Tony in 2002 for “The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia?”

He told Warren Allen Smith, editor of Who’s Who in Hell (2000), that he was a “nominal Quaker” because he admired their pacifism, and that while he thinks Jesus lived and is interested in his outlook, he did not accept “all that divinity stuff.” (Dec. 10, 1996)

In his 2011 acceptance speech for the Lambda Literary Foundation’s Pioneer Award for Lifetime Achievement, Albee said: “A writer who happens to be gay or lesbian must be able to transcend self. I am not a gay writer. I am a writer who happens to be gay.” His longtime partner, sculptor Jonathan Thomas, died in 2005 from bladder cancer. Albee also had relationships with composer William Flanagan and playwright Terrence McNally during the 1950s and early 1960s. Albee died at his home at age 88 in Montauk, N.Y. (D. 2016)

“The result is a touching, humorous, and honest tribute to a woman who was a pioneer for free-thinking females everywhere, but also stood strongly on her own as one of the 20th century’s greatest artistic minds.”

— From a description of Albee's 2001 play "Occupant" about artist Louise Nevelson (Berkshire On Stage, Oct. 1, 2018)

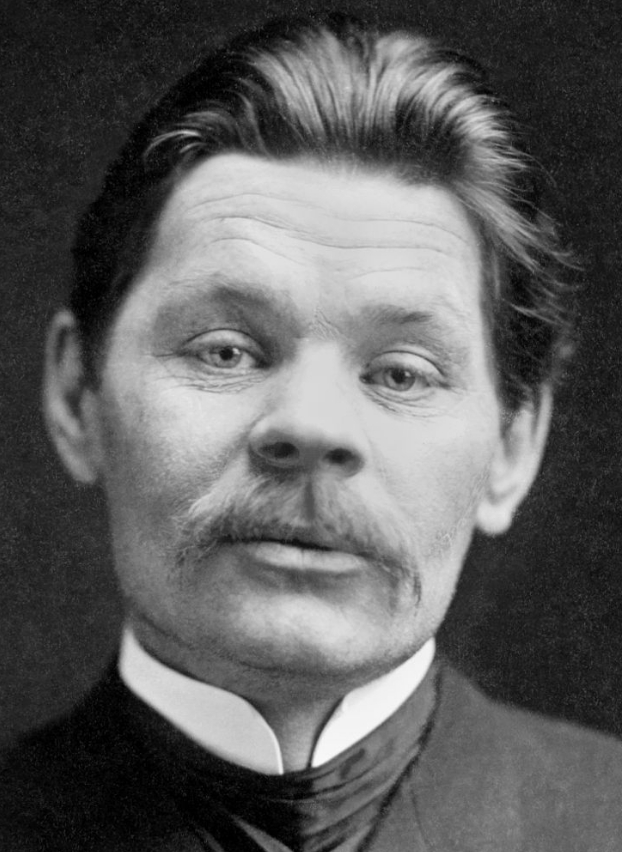

Maxim Gorky

On this date in 1868, Maxim Gorky, né Alexei Maximovitch Peshkov, was born in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia. After his father died when he was 5, he was sent to live with his maternal grandparents. His grandfather made him quit school at age 8 to go to work. At 12 he ran away and endured so many bitter hardships trying to survive that he later adopted the name “Gorky,” which means “The Bitter One.”

After trying unsuccessfully at age 21 to commit suicide by shooting himself, he suffered from lifelong bouts of tuberculosis as the result of damage to his lungs. Gorky undertook a two-year walking journey as a “tramp,” becoming familiar with Russia’s oppressed underclass. At 24 he became a reporter and began writing sympathetically about the outcasts, derelicts, petty criminals and prostitutes he had encountered, thus becoming a folk hero. His first collection of short stories was published to great acclaim in 1898.

Anton Chekhov befriended Gorky, introducing him to theatrical producers, who invited him to write his first plays. “The Smug Citizen” (1902), created an uproar, although “The Lower Depths” (1902) has endured. He was invited by a host of writers and dignitaries to speak in the U.S. in 1906, where the New York World newspaper pilloried him for traveling with the actress Maria Andreyeva, his common-law wife. Gorky had been amicably separated from his first wife for years but his Finnish divorce wasn’t recoginzed by the Russian Orthodox Church. Many sponsors withdrew their support, although some, such as H.G. Wells, stood by him.

He was married to Yekaterina Peshkova from 1896 to 1903 and to Andreyeva from 1903 to 1919. He had three sons, Zinovy, Maxim and Yuri, and two daughters, Yekaterina and Catherine.

Gorky, sympathetic to the Marxist cause to overthrow the government, was periodically jailed and finally exiled for several years. Critical of the Bolsheviks and Lenin, he went on a self-imposed exile throughout the 1920s, until one of his harshest critics, Stalin, invited him home. Although Gorky was criticized for endorsing some of Stalin’s policies, he is credited with saving the lives of several writers.

Gorky’s books and plays include Summer Folk (1903), Barbarians (1906), Enemies (1906), The Last Ones (1908), The Counterfeit Coin (1926), Yegor Bulychov (1931), and an autobiographical trilogy, My Childhood (1914), In the World (1916), and My Universities (1923).

In Maxim Gorky: A Political Biography (1999), Tova Yedlin wrote: “Gorky had long rejected all organized religions. Yet he was not a materialist, and thus he could not be satisfied with Marx’s ideas on religion. When asked to express his views about religion in a questionnaire sent by the French journal Mercure de France on April 15, 1907, Gorky replied that he was opposed to the existing religions of Moses, Christ, and Mohammed.”

The circumstances of his death in 1936 were murky. While it is possible he may finally have succumbed to tuberculosis or natural causes, he may also have been ordered killed by Stalin. (D. 1936)

“Gorky hated religion with all the passion of a former God-builder. Probably no other Russian writer … expressed so many angry words about God, religion, and the church.”

— Evgeniĭ Aleksandrovich Dobrenko, "Political Economy of Socialist Realism" (2007)

Henrik Ibsen

On this date in 1828, Henrik Ibsen was born in Norway. The playwright, a social critic who in his later years pioneered realist drama, produced a roster of literary classics. His plays include “Brand” (1866), “Peer Gynt” (1867), “A Doll’s House” (1879), “Enemy of the People” (1882) and “Hedda Gabler” (1890). Reportedly becoming a freethinker as a teenager, Ibsen was later influenced by Georg Brandes, penning “The Emperor and the Galilaean” (1873). Its disillusioned protagonist sets out to overthrow Christianity.

In his play “Ghosts” (1881) he wrote, “It’s not only what we have inherited from our father and mother that walks in us. It’s all sorts of dead ideas, and lifeless old beliefs, and so forth. They have no vitality, but they cling to us all the same, and we can’t get rid of them.” In “The Pillars of Society” (1877) he wrote, “The spirit of truth and the spirit of freedom — these are the pillars of society.”

Ibsen married Suzannah Thoresen when he was 30 and had a son, Sigurd, who as prime minister played a central role in 1905 in the dissolution of the union between Norway and Sweden. He died at home in Oslo at age 78, six years after the first of a series of strokes. (D. 1906)

“The state has its root in Time: it will have its culmination in Time. Greater things than it will fall; all religion will fall. Neither the conceptions of morality nor those of art are eternal. To how much are we really obliged to pin our faith?

— Ibsen letter to Georg Brandes (Sept. 24, 1871)

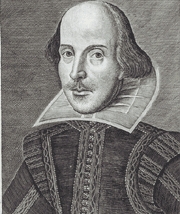

William Shakespeare

On this date in 1564, William Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England. The master playwright was eulogized by 19th-century agnostic orator Robert Green Ingersoll. In one of his famous lectures, Ingersoll said that when he read Shakespeare, “I beheld a new heaven and a new earth.” (The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, Interviews, Vol. IV) “Think of the different influence on men between reading Deuteronomy and ‘Hamlet’ and ‘King Lear.’ … The church teaches obedience. The man who reads Shakespeare has his intellectual horizon enlarged,” said Ingersoll in Vol. VIII.

No one knows Shakespeare’s personal religious views, although he certainly was not orthodox. He was born under the rule of Elizabeth I, who was Protestant and outlawed Catholicism, and was succeeded by James I, who continued Elizabeth’s policies despite his mother Mary Stuart’s Catholicism. Shakespeare’s parents were likely covert Catholics. His father John was close friends with William Catesby, father of the head conspirator in the Catholic “gunpowder plot” to blow the Protestant monarchy of James I to smithereens in November 1605.

Shakespeare put many different types of sentiments into the mouths of his characters. The bard’s philosophy seems most succinctly described in the famous “Seven Ages of Man” speech from “As You Like It,” which begins: “All the world’s a stage / And all the men and women merely players: / They have their exits and their entrances …” ending with “mere oblivion. / Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.”

In “King Lear,” the Duke of Gloucester laments in Act 4, Scene 1, “As flies to wanton boys, are we to the gods; they kill us for their sport.” Victorian poet, playwright and novelist Algernon Swinburne put it this way: “Shakespeare was in the genuine sense — that is, in the best and highest and widest meaning of the word, a Freethinker.” He died unexpectedly at age 52, cause unknown. (D. 1616)

"In religion, what damned error, but some sober brow will bless it and approve it with a text, hiding the grossness with fair ornament?"

— Bassanio in "The Merchant of Venice," Act III, Scene II (c. 1596-99)

Lorraine Hansberry

On this date in 1930, Lorraine Hansberry was born in Chicago, the daughter of civil rights activists and intellectuals. Her play, “A Raisin in the Sun” (1959), the first drama by a black woman to be produced on Broadway and winner of the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award, was loosely based on her own experiences. When she was 8, her parents bought a house in a white neighborhood, where Lorraine witnessed a racist mob and her parents’ resulting civil rights case.

She studied at the University of Wisconsin for two years, then moved to New York to become a writer, working as an associate editor of Paul Robeson‘s “Freedom.” She married Robert Nemiroff in 1953, whom she met on the picket line while protesting discrimination at New York University. Hansberry divorced her husband in 1964.

Hansberry selected the title of her play from a line in a poem by Langston Hughes: “What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun, Or does it explode?” Sidney Poitier starred in both the play and film version. The play’s central protagonist is Beneatha, an eager young woman determined to fight social convention and go to medical school. Beneatha is a “self-avowed” atheist (who gets slapped by her mother for admitting it).

Hansberry wrote “The Drinking Gourd,” commissioned by the National Broadcasting Co., in 1959. About the American slave trade, it was considered too hot for television and was never produced. Her play, “The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window” (1964), was about a Jewish intellectual. It played on Broadway while Hansberry was being hospitalized for the cancer that cut her life short at age 34. “To Be Young, Gifted, and Black” was posthumously adapted from her writings and was produced off-Broadway in 1969, also appearing in book form in 1970. (D.1965)

“I get tired of God getting credit for all the things the human race achieves.”

— Hansberry, "Raisin in the Sun" (words ascribed to Beneatha)

Harvey Fierstein

On this date in 1952, actor, comedian, playwright and LGBT activist Harvey Forbes Fierstein was born in Brooklyn, N.Y. He debuted in the Andy Warhol play “Pork” in 1971. He has since been in over 60 off-off-Broadway plays, including his own productions. One of his three-act plays, “The Torch Song Trilogy,” in which he played a gay man, opened off-off-Broadway in 1980, transferred to Broadway and won Fierstein two Tony Awards, an Obie, a Dramatist Guild Award, two Drama Desk Awards and a nomination for the prestigious Laurence Olivier Award.

The hugely successful play was made into a movie in 1988, with Fierstein writing the screenplay and co-starring with Matthew Broderick and Anne Bancroft. He earned his third Tony for his book of the musical “La Cage aux Folles.” He picked up a fourth Tony for his portrayal of Edna Turnblad in the Broadway version of “Hairspray” (2003).

In addition to his theater work, Fierstein is a popular face (and voice) in films, including such hits as “Mrs. Doubtfire” (1993), “Bullets Over Broadway” (1994), “Independence Day” (1996), “Death to Smoochy” (2002) and “Duplex” (2003), which starred Ben Stiller and Drew Barrymore. His trademark voice has lent its popularity to TV shows like “The Simpsons,” “How I Met Your Mother” and “Family Guy” and animated movies such as Disney’s “Mulan” (1998), “Kingdom Hearts II” (2005) and “Farce of the Penguins” (2006). He won an Emmy for narrating the documentary “The Times of Harvey Milk” (1984).

Fierstein is a leading gay rights activist and has consistently made his views on religion known. In an interview about playing Tevye in the Broadway revival of “Fiddler on the Roof,” when asked if he was generally religious, Fierstein said: “No, but I am Jewish. … I don’t believe in God, I don’t believe in heaven or hell.”

In a 2022 People magazine interview, Fierstein stated, “I’m still confused as to whether I’m a man or a woman,” and said that as a child he often wondered if he’d been born in the wrong body. “When I was a kid, I was attracted to men. I didn’t feel like a boy was supposed to feel. Then I found out about gay. So that was enough for me for then.”

PHOTO: by David Shinbone photo under CC 3.0.

“We are lucky enough to be living in a country that not only guarantees the freedom to practice religion as we see fit, but also freedom FROM religious zealots who would persecute and prosecute and even physically harm those of us who do not believe as they do. … Predicating patriotism on a citizen’s belief in God is as anti-American as judging him on the color of his skin. It is wrong. It is useless. It is unconstitutional.”

— Fierstein, "In the Life" broadcast by Generation Q (November 2004)

Tom Stoppard

On this date in 1937, playwright Tom Stoppard (né Tomás Straüssler) was born in Zlin, Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic), to Martha Becková and Eugen Straüssler, a physician. His parents were nonpracticing Jews. “His mother kept her own ‘Jewishness’ a secret; and so, Tom grew up with a safe sense that his relationship to Jewishness was past, distant and patrilineal.” (jewthink.org, March 18,2021) All four of his grandparents and three maternal aunts died in the Holocaust.

The Straüsslers fled Czechoslovakia in 1938 to escape the Nazis and then to Singapore, where the shoe company his father worked for had a plant. The family, except for Eugen, soon fled again as the Japanese approached Singapore. Eugen drowned in 1942 when the Japanese bombed the ship he was leaving on. By then, the rest of the family had evacuated to India.

In 1945 his mother married British Army Major Kenneth Stoppard, and she and her sons took his surname, moving to England the next year. His stepfather would prove to be anti-SemiticStoppard left school at age 17 to work as a journalist and drama critic, which introduced him to the theatrical world. He started writing plays for radio, TV and the theater.

A Ford Foundation grant in 1964 enabled him to spend five months writing a one-act play titled “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Meet King Lear,” which evolved into “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead,” which won the 1968 Tony Award for Best Play. A string of successful and award-winning plays followed, including “Jumpers” (1972), “Travesties” (1974), “Every Good Boy Deserves Favour” (1977), “The Real Thing” (1982), “Arcadia” (1993), “The Invention of Love” (1997), “The Coast of Utopia” (2002 trilogy), “Rock ‘n’ Roll” (2006), “The Hard Problem” (2015) and “Leopoldstadt” (2020).

Stoppard translated many plays, including those of future Czech President Václav Havel, into English in the 1980s, also a time when he joined Outrapo, a semi-serious French movement to improve actors’ stage technique through science. His 2013 radio production “Darkside” celebrated the 40th anniversary of Pink Floyd’s album “The Dark Side of the Moon.” His only novel, Lord Malquist and Mr Moon (1966), featured a donkey-riding Irishman claiming to be the risen Christ.

He has also co-written over a dozen screenplays, including for the Oscar-winning “Shakespeare in Love” (1998). He wrote and directed “Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead,” the 1990 film adaptation of his play. His papers are housed at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth in 1997, entitling him to put “Sir” before his name.

Stoppard married Josie Ingle, a nurse (1965–1972), Miriam Stern, a physician and media consultant (1972–92) and Sabrina Guinness, an Irish television producer, in 2014. He has two sons from each of his first two marriages.

He once said he tries to live “as if” God existed, akin to Pascal’s Wager, but makes no claim to faith. “I don’t think of myself as being particularly spiritual. I’m quite hard-headed in fact, but I have a sense of, with great respect, science having a long honourable history of self certainty which needs modulating continually and I’m just very very curious about the unknown.” (This View of Life online magazine, May 2, 2015)

PHOTO: Stoppard in 1990 at the Venice Film Festival; Gorup de Besanez photo under CC 3.0.

"I’ve always thought that the idea of God is absolutely preposterous, but slightly more plausible than the alternative proposition that, given enough time, some green slime could write Shakespeare’s sonnets.”

— New York Times interview (April 23, 1974)

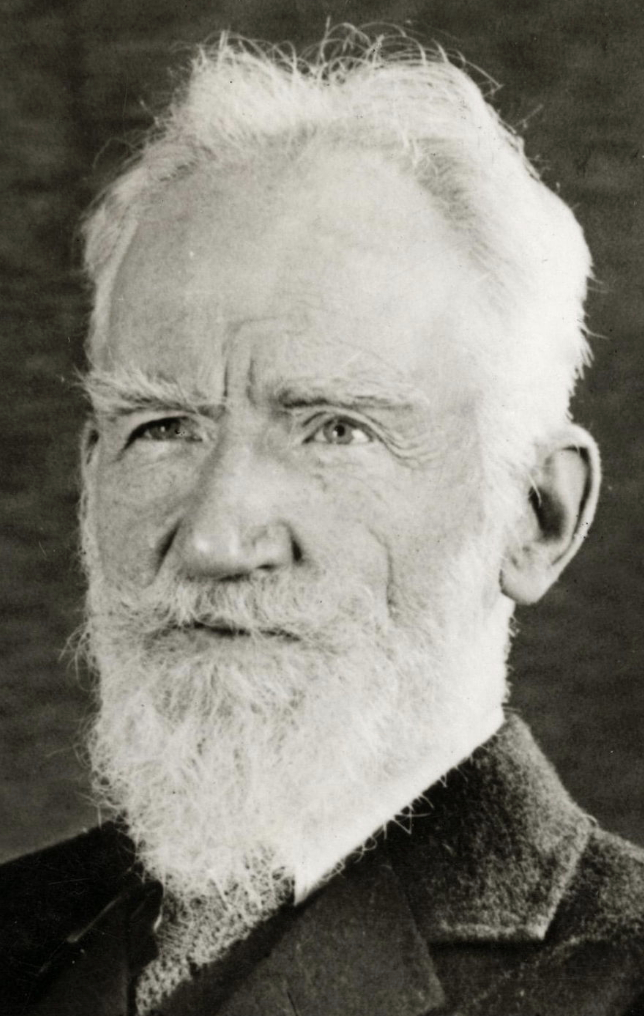

George Bernard Shaw

On this date in 1856, George Bernard Shaw was born in Dublin, Ireland. After his parents separated, Shaw moved to London at age 20, where he built a long, distinguished and often controversial career as a critic, journalist, stage director, women’s rights advocate, war critic, religion critic and, most notably, playwright. Shaw wrote over 50 plays ranging from tragedies to comedies to powerful social critiques. Some of his most famous productions include “Man and Superman” (1903), “Saint Joan” (1923), “Caesar and Cleopatra” (1901), “Major Barbara” (1905) and “Pygmalion” (1913). Shaw’s strong allegiance to socialism as a means to improve the lives of the working class was evident throughout much of his literary and dramatic work.

Shaw, along with fellow freethinkers Beatrice and Sidney Webb and others had leadership roles in the Fabian Society, a socialist movement which attracted Bertrand Russell, Virginia Woolf and Annie Besant. Together with atheist Graham Wallas and the Webbs, Shaw co-founded the London School of Economics in 1895 to promote “the betterment of society.” Shaw won the Nobel Prize (though he refused the monetary award) for his contribution to literature in 1925 and an Academy Award for Best Screenplay in 1938 for the film “Pygmalion.”

Shaw’s work sometimes overtly criticized religion, such as his play “Androcles and the Lion” (1912) and the short story “The Adventures of the Black Girl in Search for God.” (1938). While Shaw claimed to have become an atheist at age 10, he started to reject atheism and classify himself as a mystic. But throughout most of his life he remained critical of organized religion and especially the Christian church. “There is nothing in religion but fiction.” (Back to Methuselah, 1924)

Near the end of his long life, Shaw requested that “the form of a cross or any other instrument of torture or symbol of blood sacrifice” be omitted from all memorials to him. (D. 1950)

PHOTO: Shaw at 80.

“It is not disbelief that is dangerous to society, it is belief.”

— Shaw, "Androcles and the Lion" (1912)

Howard Zinn

On this date in 1922, historian, author and peace activist Howard Zinn was born in New York City to Jewish immigrants. As a 17-year-old, Zinn attended a political rally in Times Square at the urging of neighborhood Communists and was knocked unconscious by police. He joined the Army Air Corps in 1943, received an Air Medal and, upon returning home, placed his medal and military papers in a folder on which he wrote “Never again.”

Zinn attended New York University and received a doctorate in history from Columbia University. He became chair of the history and social sciences department of Spelman College, the historically black college for women in segregated Atlanta, in 1956. He participated in the civil rights movement, served on the executive committee for SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) and inspired many of his students, including Alice Walker.

Fired for “insubordination” from Spelman in 1963 (for his criticism of the school’s failure to participate in the civil rights movement), Zinn took a position teaching history at Boston University, which he held until retirement in 1988.

An aggressive and early opponent of the Vietnam War (and war in general) and champion of liberal causes, Zinn’s 1967 Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal, was the first book calling for immediate withdrawal from the war with no exceptions. His A People’s History of the United States, published in 1980 with a small printing and little promotion, was a best-seller, hitting 1 million in sales by 2003. In his 1994 autobiography You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, Zinn wrote, “I wanted students to leave my classes not just better informed, but more prepared to relinquish the safety of silence, more prepared to speak up, to act against injustice wherever they saw it.”

While his publications were numerous, some of the highlights include the plays “Emma” (1976), about radical feminist and atheist Emma Goldman, “Daughter of Venus” (1985) and “Marx in Soho: A Play on History” (1999), and books such as Artists in Times of War (2003), History Matters: Conversations on History and Politics (2006), and Failure to Quit: Reflections of an Optimistic Historian (1993).

Zinn received the 1958 Albert J. Beveridge Prize from the American Historical Association for his book, LaGuardia in Congress; the 1998 Eugene V. Debs Award from the Debs Foundation; the Upton Sinclair Award in 1999; and the 1998 Lannan Literary Award. Zinn’s wife and lifetime collaborator, Roslyn, died in 2008. Zinn died of a heart attack at age 87 while swimming in a hotel pool in Santa Monica, Calif. (D. 2010)

PHOTO:Zinn at the Pathfinder Bookstore in Los Angeles in 2000. CC 4.0

“If I was promised that we could sit with Marx in some great Deli Haus in the hereafter, I might believe in it! Sure, I find inspiration in Jewish stories of hope, also in the Christian pacifism of the Berrigans, also in Taoism and Buddhism. I identify as a Jew, but not on religious grounds. Yes, I believe, as Pascal said, ‘The heart has its reasons which reason cannot know.’ There are limits to reason. There is mystery, there is passion, there is something spiritual in the arts — but it is not connected to Judaism or any other religion.”

— Tikkun magazine interview, "Howard Zinn on Fixing What's Wrong" (May 17, 2006)

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

On this date in 1749, Germany’s most famous poet, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, was born in Frankfurt am Main, to a comfortable bourgeois family. He began studying law at Leipzig University at the age of 16 and practiced law briefly before devoting most of his life to writing poetry, plays and novels. In 1773, Goethe wrote the powerful poem “Prometheus,” which urged human beings to believe in themselves more than in gods.

His first novel was The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774), a semi-autobiographical tragedy about a doomed love affair. A line from that novel: “We are so constituted that we believe the most incredible things: and, once they are engraved upon the memory, woe to him who would endeavor to erase them.” In his 1797 Hermann and Dorothea, Goethe observed: “The happy do not believe in miracles.” Goethe typified the Sturm und Drang romantic movement, celebrating the individual. The Grand Duke of Weimar appointed him an administrator in 1775, where, according to some historians, Goethe turned Weimar into “the Athens of Germany.”

Goethe was keenly interested in the natural sciences and in his studies discovered the human intermaxillary bone (also known as the Goethe bone, adjacent to the incisors). After a sojourn in Italy from 1786 to 1788 he returned to his art, starting a journal inspired by Christopher Marlowe‘s play “Faust,” Goethe wrote part 1 of his most famous play, published in 1808. Part 2 was published in 1832. From Part 1, Scene 9: “The church alone beyond all question / Has for ill-gotten gains the right digestion.”

Goethe’s religious beliefs were complicated and changed at various periods in his long life. He was raised Lutheran and was quite devout when young but grew to have problems with Christianity’s dogma, hierarchy and superstitious aspects. He revered Spinoza, whom Nietzsche often paired with Goethe. His later spiritual perspective incorporated pantheism (heavily influenced by Spinoza), humanism and elements of Western esotericism, as seen most vividly in part 2 of “Faust.”

“Goethe was a freethinker who believed that one could be inwardly Christian without following any of the Christian churches, many of whose central teachings he firmly opposed, sharply distinguishing between Christ and the tenets of Christian theology, and criticizing its history as a ‘mishmash of fallacy and violence,’ ” states the 1982 German publication Goethe’s Poems in Chronological Order.

He died at age 82 of apparent heart failure in Weimar. Of his five children, only a son, August, survived into adulthood. (D. 1832)

In the wilderness a holy man

To his surprise met a servant of Pan,

A goat-footed faun, who spoke with grace;

“Lord, pray for me and for my race,

That we in heaven find a place:

We thirst for God’s eternal bliss.”

The holy man made answer to this:

“How can I grant thy bold petition,

For thou canst hardly gain admission

In heaven yonder where angels salute:

For lo! thou hast a cloven foot.”

Undaunted the wild man made the plea

“Why should my hoof offensive be?

I’ve seen great numbers that went straight

With asses’ heads through heaven’s gate.”— Goethe poking fun at pietists claiming his cloven-hoofed paganism would bar him from heaven. "Goethe: With Special Consideration of His Philosophy" by Paul Carus (1915)

Gore Vidal

On this date in 1925, writer Eugene Louis Vidal was born at West Point, N.Y., where his father was the first aeronautics instructor at the U.S. Military Academy. (He dropped his first and middle names when he was 14, exchanging them for Gore.) He largely grew up in the home of his grandfather, Sen. Thomas P. Gore, D-Okla. He graduated from Philips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire and joined the Enlisted Reserve Corps.

His first novel, Williwaw, was published when he was only 19. It was followed by the wave-making The City and the Pillar (1948), which featured a sympathetic gay protagonist. Vidal was the prolific author of many other novels and plays, many based on history and politics, and worked in TV and the movies. His novels include Julian (1964), Myra Breckenridge (1968), Burr (1974) and Live from Golgotha (1992), an irreverent satire imagining New Testament events if reported on TV.

A cousin of former Vice President Al Gore, he made some political runs, including a try for the U.S. Senate seat in California in which he came in second out of nine in the 1982 race. Vidal was perhaps best-known as a public intellectual and for his refreshing and acerbic interviews and one-liners, such as his famous remark about Ronald Reagan: “A triumph of the embalmer’s art.” “Probably no American writer since Franklin has derided, ridiculed, and mocked Americans more skillfully and more often than Vidal,” wrote Gordon S. Wood. (The New York Times, Dec. 14, 2003)

Vidal’s essays, such as “Pink Triangle and Yellow Star” (1981), are collected in Armageddon (1987). Palimpsest (1995) was his well-received autobiography. He rarely missed a chance to diss religion or monotheism: “I regard monotheism as the greatest disaster ever to befall the human race. I see no good in Judaism, Christianity, or Islam.” (Letter to Warren Allen Smith, 1954, Who’s Who in Hell.) (D. 2012)

PHOTO: Vidal at 23 in 1948; Carl Van Vechten photo.

"Christianity is such a silly religion."

— Vidal, Time magazine (Sept. 28, 1992)

Harold Pinter

On this date in 1930, playwright Harold Pinter was born in East London to a Jewish family. He briefly studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts and acted under the name “David Baron.” The playwright, director, actor, poet and political activist wrote 29 plays and 21 screenplays and directed 27 theater productions. His plays include “The Birthday Party,” “The Caretaker,” “The Homecoming” and “The Betrayal.” Screenplays include “The Servant,” The Go-Between,” “The French Lieutenant’s Woman” and “The Handmaid’s Tale.”

Pinter’s many awards include the Wilfred Owen Prize for Poetry (opposing the Iraq war), the Shakespeare Prize (Hamburg), the European Prize for Literature (Vienna) and the Laurence Olivier Award. He was married to Lady Antonia Fraser. Pinter continued to dabble in acting, including portraying Sir Thomas Bertrand in the film “Mansfield Park.” His fight against cancer, he said, had fortified his commitment to political activism. That activism included signing a letter to the BBC asking that its daily “Thought for the Day” should also include those with secular views. D. 2008.

PHOTO: Pinter in the Netherlands in 1962; Dutch National Archives.

"You know, I had my bar mitzvah when I was thirteen and I never entered a synagogue again. I’ve been to one or two marriages, I think, but I’ve never had anything to do with it."

— Pinter interview with Ramona Koval, "Books and Writing," Radio National (Sept. 15, 2002)

Oscar Wilde

On this date in 1854, writer Oscar Wilde was born in Ireland. He studied at Trinity College on a scholarship. In 1874 he was awarded a scholarship to Oxford. His first book of poems was published in 1881 and he spent a year lecturing on aesthetics in the United States. Wilde married in 1884 and fathered two sons, working for a magazine and writing children’s stories. His only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, was published in 1890. This was followed by his successful plays: “Lady Windermere’s Fan“ (1892), “A Woman of No Importance” (1893), “Salome” (1894), “An Ideal Husband” (1895) and “The Importance of Being Earnest” (1895).

In 1895 he sued the father of his male lover for libel after Wilde was accused of homosexuality. Wilde dropped the ill-advised lawsuit but was then charged criminally and convicted of gross indecency and sentenced to two years’ hard labor. His health was broken by the ordeal. He wrote “The Ballad of Reading Gaol” about it in 1898. Penniless, he moved to the continent, where he died of meningitis at age 46. On his deathbed, the lifelong skeptic, who had written “it is better for the artist not to live with popes,” (“The Soul of Man Under Socialism”) converted to Catholicism, a gesture perhaps imputed to his brain condition.

A master of the epigram, Wilde is known for such one-liners as “To love oneself is the beginning of a life-long romance.” “I think that God in creating Man somewhat overestimated his ability.” “The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it.” “He hasn’t a single redeeming vice.” “There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.” He reputedly said on his deathbed, “Either that wallpaper goes or I do.”

In his review of “Oscar Wilde: A Life” by Matthew Sturgis, David Hare wrote: “Those of us who love him are most moved by his generosity. He really did give extravagant sums of money to every beggar he passed, and was bewildered when, in his last years, acquaintances did not show him the same largess he had once extended to strangers. The act of exercising practical, daily kindness was at the heart both of his beliefs and of his way of life.” (New York Times, Oct. 13, 2021)

Hare added, “He brought to literature a liberating philosophy that struck hard at Victorian society, but also at our own. He did not believe that morality consisted of judging other people’s faults. He believed it consisted in judging your own.”

Of religion he wrote in “The Critic as Artist” in 1891: “A thing is not necessarily true because a man dies for it.” “Truth, in matters of religion, is simply the opinion that has survived.” “There is no sin except stupidity.” (D. 1900)

"Science is the record of dead religions."

— Wilde, "Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young" (1894)

Eugene O’Neill

On this date in 1888, Eugene O’Neill was born in New York City in a hotel on Broadway, the third son of popular actor James O’Neill. As a youngster he traveled with his father, then was sent to a Catholic boarding school. O’Neill entered Princeton in 1906. After he was expelled he set off on adventures prospecting for gold in Honduras, working as a sailor and a variety of other jobs. While recovering from a bout of tuberculosis, O’Neill, influenced by his reading of Ibsen and other dramatists, determined to become a playwright.

He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1936 and four Pulitzer Prizes for Beyond the Horizon (1920), Anna Christie (1922), Strange Interlude (1928) and Long Day’s Journey into Night, written in 1939 but awarded posthumously in 1957. Some of his other works include Mourning Becomes Electra (1931), Ah, Wilderness! (1933), The Iceman Cometh (1936) and A Moon for the Misbegotten (1943).

O’Neill had three wives and three children before dying at age 65 after years of poor health exacerbated by alcoholism. He died in Room 401 in the Sheraton Hotel in Boston. According to biographer Louis Scheaffer, his whispered last words were “I knew it. I knew it. Born in a goddamn hotel room and dying in a hotel room.” (D. 1953)

"When I’m dying, don’t let a priest or Protestant minister or Salvation Army captain near me. Let me die in dignity. Keep it as simple and brief as possible. No fuss, no man of God there. If there is a God, I’ll see him and we’ll talk things over."

— O'Neill's instructions to his wife Carlotta, "O'Neill: Son and Artist" by Louis Scheaffer (2002)

Georg Buchner

On this date in 1813, playwright and poet Karl Georg Buchner was born in Goddelau, Germany. The eldest child, his siblings included freethinkers Alexander and Ludwig (and Louise, Mathilde and Wilhelm). He studied medicine in Strasbourg and Gissen. An intense student of Spinoza’s writings, Buchner earned a doctorate in philosophy and lectured in natural history in Zurich, Switzerland. Having developed a passion for radical politics, for a short time he edited Der Hessische Landbote, a pamphlet with the well-known Revolutionary-era slogan “Peace to the Huts and War to the Palaces.”

Despite living only until age 23, Buchner gained a reputation as a powerful playwright and, though he only wrote one, novella author. He wrote the play “Leonce and Lena” (1838) and part of a play called “Woyzeck” (published posthumously in 1879). Some of his other plays have been lost, but “Danton’s Death” (1835), was a well-received work that depicted an atheistic Thomas Paine (whom he called “Payne”). “Danton’s Death” was written about two years before his own death and, by the author’s claim, was completed in less than five weeks.

While a political refugee in Zurich, he died of typhoid fever at age 23. In 1923 Buchner’s hometown of Darmstadt, Germany, created the Georg Buchner Prize for literature, which is still a prestigious award. (D. 1837)

Mercier: But what about morality?

Payne: First you adduce morality as a proof of God, and then cite God in support of morality. You reason in a beautiful circle, like a dog biting his own tail.— Buchner's "Payne" in "Danton's Death"

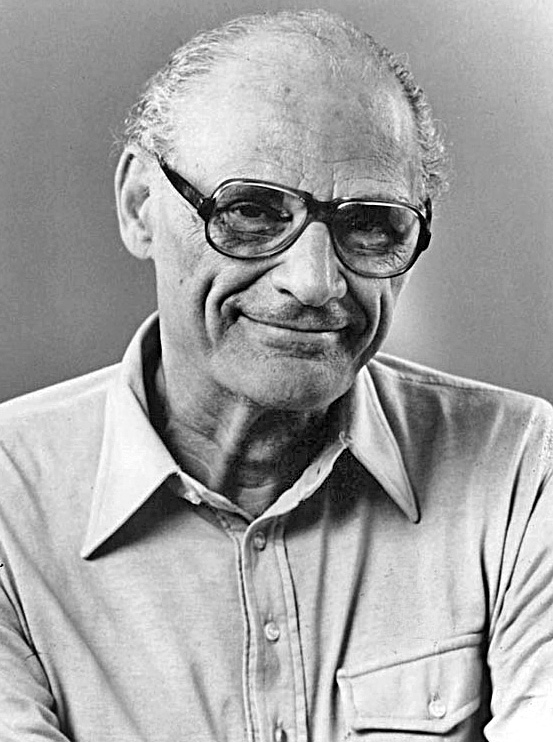

Arthur Miller

On this date in 1915, essayist and playwright Arthur Asher Miller was born into a Polish-Jewish family in Harlem, New York. As a child growing up in New York City, Miller delivered bread in the mornings before school to help his family, which had lost nearly everything in the financial crash of 1929. His career as a playwright began at the University of Michigan, where he won the Avery Hopwood Award for the play “No Villain” (1936), which he wrote as a sophomore. He won a second Hopwood for the play “Honors at Dawn” (1936).

Miller earned his first Tony Award (for best author) and Broadway hit with “All My Sons” (1947). A year later, after building his own studio in Roxbury, Conn., he completed “Death of a Salesman” (1949). It was an instant commercial and critical hit, and Miller was awarded his second Tony, a New York Drama Circle Critics’ Award and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. A prolific playwright and screen writer, he wrote his first play in 1936 and his last in 2004.

His 1953 play “The Crucible” compared the national hysteria surrounding Communist Party membership to the Salem witch trials, which led to him being called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Miller refused to “name names” and was convicted of contempt of Congress, which was overturned on appeal.

Miller was married to Mary Slattery from 1940 to 1956, when he married the film star Marilyn Monroe. They divorced in 1961, 19 months before she died. He had written the screenplay for “The Misfits,” the last movie she completed. He married photographer Inge Morath in 1962. Miller had four children, including a son born in 1966 with Down syndrome. He had Daniel institutionalized against his mother’s wishes and refused to visit him.

The couple kept their son’s birth a secret, finally revealed in 2007 by Vanity Fair. As of this writing in 2019, Daniel was doing well and living with a foster family in Connecticut. The 2018 play “The Fall” by Bernard Weintraub explored the situation.

Miller was an outspoken atheist for much of his life. In 2004, a year before his death at age 89, he participated in a BBC documentary titled “The Atheism Tapes.” Miller talked with Sir Jonathan Miller, an English neurologist and theater director, about his atheism and Jewish background. (D. 2005)

"The wedding of Christianity or Judaism with nationalism is lethal in my opinion."

— Miller, "The Atheism Tapes" (2004)

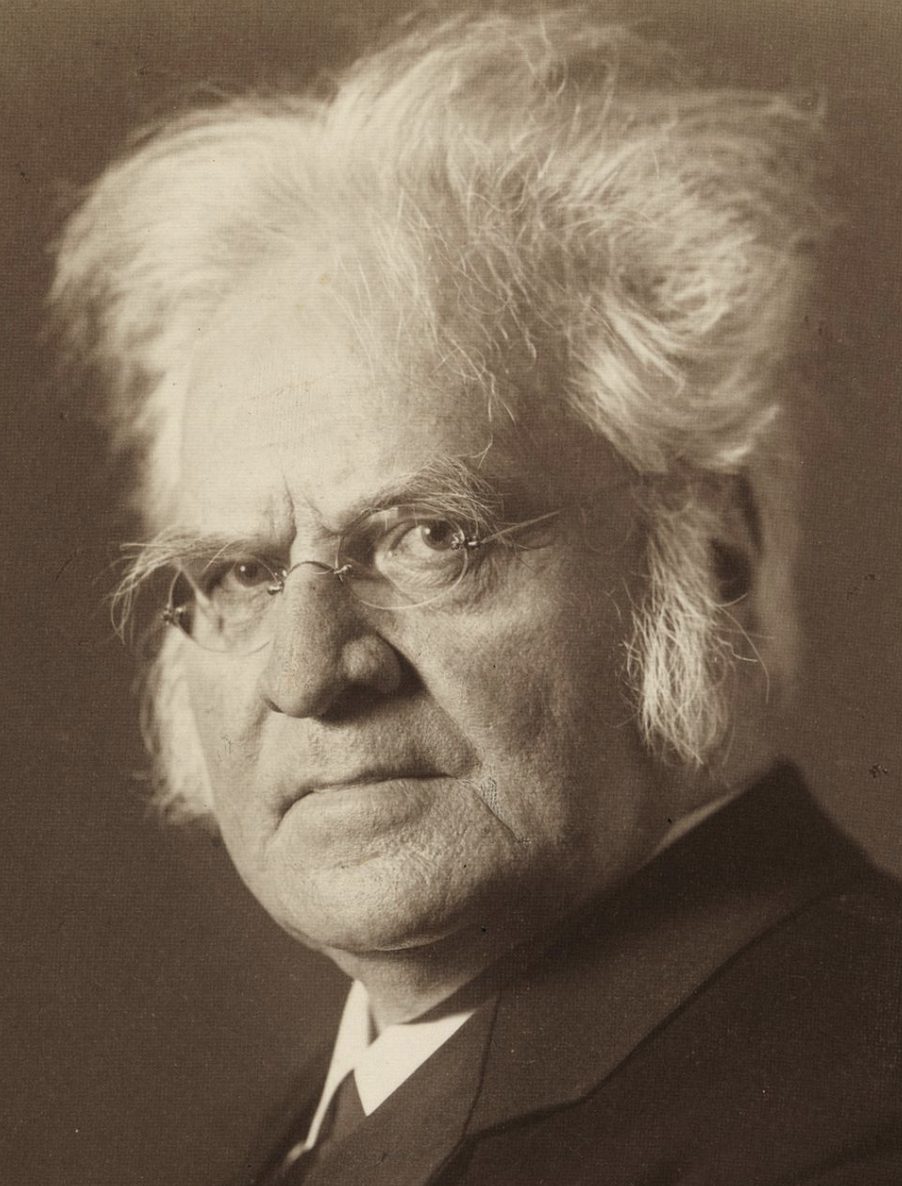

Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson

On this date in 1832, Nobel Laureate Bjørnstjerne Martinius Bjørnson was born in Norway. The son of a Lutheran minister, Bjørnson was a journalist, then a playwright and novelist who also directed theater. He wrote the first realistic contemporary play, with Ibsen following suit. Bjørnson’s plays were the first Norwegian works to be performed outside Scandinavia. Standing next to Ibsen in acclaim, he became what freethought historian Joseph McCabe termed “an aggressive Agnostic” in 1875 after reading Herbert Spencer.

His story “Dust” (1882), showed the harm of religious influence. Bjørnson wrote “Whence Came the Miracles of the New Testament?” (1882), translated Ingersoll and was an honorary associate of the Rationalist Press Association. For three decades he was a leader of Norwegian republicans. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1903 “as a tribute to his noble, magnificent and versatile poetry.” (D. 1910)

Maxwell Anderson

On this date in 1888, dramatist James Maxwell Anderson was born in Atlantic, Pa., the second of eight offspring of Charlotte (née Stephenson) and William Anderson. The family moved often due to his father’s work as a Baptist minister.

A sickly child, Anderson read voraciously. After high school in Jamestown, N.D., he earned a B.A. in English literature from the University of North Dakota in 1911 and worked as a teacher and high school principal. Fired for making pacifist statements to students, he enrolled at Stanford University and received an M.A. in English lit in 1914.

He worked as a teacher and journalist for several years and was fired from several jobs for various reasons, including voicing outspoken views. He started a poetry magazine and wrote his first play, “White Desert,” in 1923, collaborating in 1924 with Laurence Stallings on the comedy-drama “What Price Glory?” It had a successful Broadway run and was adapted for the screen two years later.

Anderson’s long string of plays included the Tudor dramas “Elizabeth the Queen” (1930) and “Mary of Scotland” (1933), in which he inveighed against religious intolerance. “Winterset” (1935), inspired by the Sacco-Vanzetti case, won the 1935 New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award for Best Play. “High Tor” won the same award two years later. He was on the cover of Time magazine on Dec. 10, 1934.

He also had success as a lyricist and wrote the book for the 1938 Kurt Weill musical “Knickerbocker Holiday.” Its “September Song” became a jazz-pop standard. He wrote movie screenplays and several of his plays were adapted by Hollywood. Three versions of “Saturday’s Children” (1927) were made. “Anne of the Thousand Days” (1948) became a 1969 movie with Richard Burton and Geneviève Bujold as Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn.

His last successful Broadway play was 1954’s “The Bad Seed.” A contender for the 1955 Pulitzer Prize for Drama, it lost out to “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.”

Anderson married high school classmate Margaret Haskett in 1911 in North Dakota. They had three sons, Quentin, Alan and Terence. His early 1930s’ affair with married actress Gertrude Higger led to a split with Haskett. Anderson and Higger had a long relationship but never married. She killed herself by inhaling car fumes in 1953. Their daughter Hesper was born in 1934. He married once more, to TV production assistant Gilda Hazard in 1954.

In a 1941 essay, he called the theater “a religious institution devoted entirely to the exaltation of the spirit of man. It has no formal religion. It is a church without creed, but there is no doubt in my mind that our theater, instead of being, as the evangelical ministers used to believe, the gateway to hell, is as much a worship as the theater of the Greeks, and has exactly the same meaning in our lives.”

Anderson died at home two days after suffering a stroke at age 70 in Stamford, Conn. (D. 1959)

“I have found my religion in the theater, where I least expected to find it, and where few will credit it exists. Yet it was in these godless nineteen-twenties that I stumbled upon the only religion I have. And I came upon it in the most unlikely and supposedly godless of places.”

— Anderson essay, "By Way of Preference: The Theatre as Religion" (New York Times, Oct. 26, 1941)