former-clergy

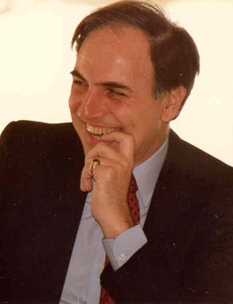

Sherwin Wine

On this date in 1928, Sherwin T. Wine was born in Detroit, Mich. He received his bachelor’s degree in philosophy from the University of Michigan, and returned for his master’s degree in philosophy in 1951. Wine attended Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati and was ordained as a rabbi in 1956. He worked as a U.S. Army chaplain in Korea (1957–58) and an assistant rabbi at Temple Beth El in Detroit (1958–60). Wine wrote many books, including Judaism Beyond God (1985) and Staying Sane in a Crazy World (1995). He lived with his partner, Richard McCains, until Wine’s death in 2007 in Morocco from a car accident.

Born to Conservative Jewish parents, Wine began questioning the idea of a god at Hebrew Union College and gradually lost his faith. He told Time magazine in 1965: “I am an atheist,” adding, “I find no adequate reason to accept the existence of a supreme person.” (Quoted in The New York Times, July 25, 2007.) Wine’s lack of belief led him to consider the concept of Humanistic Judaism, which rejects belief in God while maintaining secular Jewish traditions, culture and ethics.

“Theological beliefs have nothing to do with Jewish identity. The Jewish people encompass theists and atheists,” Wine explained in his book Celebration (2003). He elaborated on the beliefs of Humanistic Judaism: “Humanists know that they have the right and the power to be the masters of their own lives, that they have the strength to confront the world as it is and not as fantasy makes it appear, and that they have the opportunity to serve the future and not the past.”

Wine established the Birmingham Temple in 1963 in Farmington Hills, a suburb of Detroit. At the temple, which he worked at until his retirement in 2003, Wine performed services with no mention of God, replacing prayers with poetry and Torah readings with speeches on history. Humanistic Judaism is now practiced worldwide. (D. 2007)

"If I were a CEO of a company and ran it like God runs the universe, I'd be fired."

— Wine interview, The Guardian (Sept. 18, 2007)

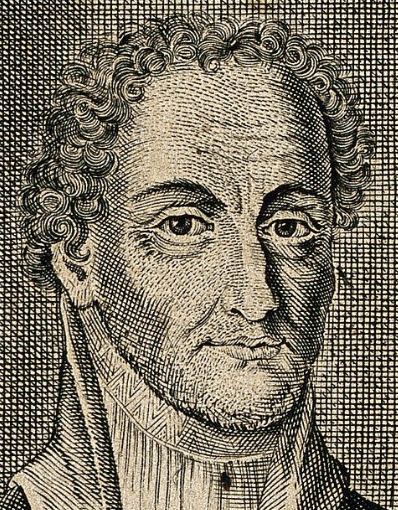

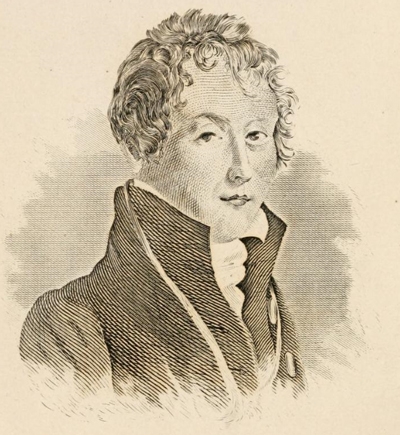

David Friedrich Strauss

On this date in 1808, theologian and author David Friedrich Strauss was born in Ludwigsburg, Germany, the son of a merchant. He pioneered scholarship questioning the historicity of Jesus. Strauss became a Lutheran vicar in 1830 and studied theology under Hegel. He was appointed to the Theological Seminary at the University at Tubingen. His two-volume work Das Leben Jesu kritisch bearbeitet (The Life of Jesus Critically Examined (1835) dissected the New Testament as largely mythical and was published to great acclaim but lost him his teaching post. The British freethinking novelist George Eliot translated its fourth edition in 1860 into English.

In 1836 he left the church. In 1841 he married mezzo-soprano opera singer Agnese Schebest. They divorced in 1846 after having two children. In his final book, The Old Faith and the New: A Confession (1872), Strauss eschewed Christianity and the concept of immortality to embrace materialist philosophy. (D. 1874)

Giulio Cesare Vanini (Died)

On this date in 1619, Catholic friar Giulio Cesare Vanini (né Lucilio Vanini) was executed for heresy in Toulose, France. Born in 1585 in Italy, Vanini was educated in philosophy and theology at Rome University and entered the Carmelite order in 1603 as Fra Gabriele before studying canon and civil law in Padua. He traveled widely throughout Europe, espousing his rationalist viewpoints and supporting himself by giving lessons. He was also an early proponent of biological evolution among the first modern thinkers to view the universe as an entity governed by natural laws.

Vanini was driven from France in 1614. After taking refuge in England, he spent 49 days in the Tower of London. Returning to Italy, he was driven out of Genoa. Vanini went to southern France, where he published a book critical of atheism in 1615 in an attempt to clear himself from charges of heresy.

The following year his second book was published, which is credited with being closer to his real views, in which he advanced a naturalistic philosophy. The book was ordered burned by the Sorbonne, and Vanini was charged with atheism. He was arrested in 1618 and sentenced to have his tongue cut off, to be strangled at the stake and to have his body reduced to ashes. It is said he refused the ministrations of a priest. (D. 1619)

Giordano Bruno (Executed)

On this date in 1600, Giordano Bruno (né Filippo Bruno) was executed for heresy. The Italian philosopher was burned alive at the stake at age 52 for refusing to recant heretical ideas. Born in 1548, he entered the Dominican Order at Naples at age 15, adopting the name of Giordano. After being accused of heresy, he fled his Italian convent and traveled throughout Europe (1576-92). During two years in England, Bruno wrote and published six dialogues, including “On the Infinite, the Universe, and Worlds” and “The Ash Wednesday Supper.”

A Copernican, he rejected Aristotelian dogma and challenged entrenched religious teachings, declaring pantheist views. Some academics today regard him as a path-blazing intellectual, others as a victim of his nonconformity. When Bruno returned to Italy in 1592, he was arrested by the Inquisition. He was imprisoned for seven years in the dungeons of Rome, where he was tortured and isolated before being executed.

Bruno was just one of the more visible martyrs and victims of church persecution. Anonymous are the thousands of women put to death as “witches.” Known to us are such martyrs as Vanini, a monk burned as an atheist in 1619; Servetus, a Spanish physician executed under Calvin’s orders in 1553 for rejecting the trinity; Scottish student Thomas Aikenhead, hanged in 1697 for saying Christ was merely human; and those persecuted in the New World. Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson were banished for advocating religious tolerance. Quaker Mary Dyer was hanged in Boston in 1660 for heresy.

A statue to Bruno was erected at the site of his execution, Campo de’ Fiori near the Vatican, in 1889 by “Freethinkers of the World.” Biographer John Kessler wrote in “Giordano Bruno: The Forgotten Philosopher” (1900): “He is one martyr whose name should lead all the rest. He was not a mere religious sectarian who was caught up in the psychology of some mob hysteria. He was a sensitive, imaginative poet, fired with the enthusiasm of a larger vision of a larger universe.”

“Perchance you who pronounce my sentence are in greater fear than I who receive it.”

— Bruno's response to his judges upon conviction, quoted in "Giordano Bruno: His Life and Thought" by Dorothea Waley Singer (1950)

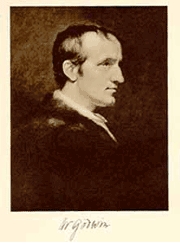

William Godwin

On this date in 1756, William Godwin was born in England, the son and grandson of strait-laced Calvinist ministers. Godwin followed in paternal footsteps, becoming a minister by age 22. His reading of atheist d’Holbach and others caused him to lose both his belief in the doctrine of eternal damnation and his ministerial position. Through further reading, Godwin gradually became godless. His Political Justice and The Enquirer (1793) argued for morality without religion and caused a scandal. He followed that philosophical book with a trail-blazing fictional detective story, Caleb Williams (1794).

He and Mary Wollstonecraft, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, secretly married in 1797. She died tragically after giving birth to their daughter Mary in 1797. Godwin and his second wife Mary Jane opened a bookshop for children and he became a proficient author of children’s books, employing a pseudonym due to his notoriety. Godwin’s life was marked by poverty and further domestic tragedies. He was responsible for a family of five children, none of whom had the same two parents.

Influenced by Coleridge, Godwin became more of a pantheist than an atheist. He died at age 80 and was buried next to Wollstonecraft in the graveyard of St. Pancras, the church where they had married in 1797. His second wife outlived him and eventually was also buried there, with the three of them sharing a headstone. (D. 1836)

“Either reason is the curse of our species, and human nature is to be regarded with horror; or it becomes us to employ our understanding and to act upon it, and to follow truth wherever it may lead us.”

— Godwin, "An Enquiry Into Political Justice, Vol. 1" (1793)

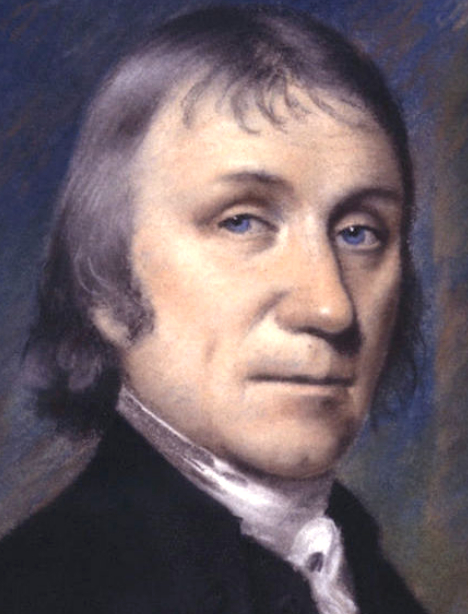

Joseph Priestley

On this date (under the Old Style calendar) in 1733, chemist and discoverer of oxygen Joseph Priestley was born in Fairhead, England, near Leeds, the oldest of six children. Destined for the ministry, Priestley realized he rejected much of Calvinism and decided to attend a Dissenting seminary, Daventry Academy. He worked as a minister while conducting scientific experiments and then secured a position at the Dissenting Academy, Warrington. He was eventually ordained and became an early founder of Unitarianism in England, at a time when Dissenters could be deprived of their citizenship and Unitarianism was not lawful.

He produced carbonated water and isolated eight gases in the air, including oxygen, and is considered to have laid the foundation for the science of chemistry. Priestley wrote The History and Present State of Electricity (1767) at the encouragement of his colleague Benjamin Franklin.

Priestley’s History of the Corruptions of Christianity (1782) was burned and reviled for its rejection of the Trinity, predestination and divine revelation. In it he averred that a pure form of Christianity had been corrupted. This was followed by History of Early Opinions Concerning Jesus Christ (1786). A General History of the Christian Church to the Fall of the Western Empire was finished in four volumes by 1803.

A defender of the French Revolution, Priestley lost his laboratory and home in Birmingham when they were stormed and burned down by mobs. His membership in the Royal Society was also withdrawn and he was burned in effigy. Priestley and his family emigrated to the U.S. in 1794 with hopes of setting up a model community but settled for building a house with a built-in lab in Northumberland, Pa., where he died at age 70 in 1804.

After weathering so much personal criticism, Priestley was notorious among freethinkers for writing about Franklin: “It is much to be lamented that a man of Dr. Franklin’s general good character and great influence should have been an unbeliever in Christianity and also have done so much as he did to make others unbelievers.” Priestley helped found the first Unitarian church in the U.S. (D. 1804)

What does Priestley mean, by an unbeliever, when he applies it to you? How much did he unbelieve himself? Gibbon had it right when he denominated his Creed, ‘scanty.’ “

— John Adams, in a letter to Thomas Jefferson (18 July 1813), "The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States, Vol.10" (1856)

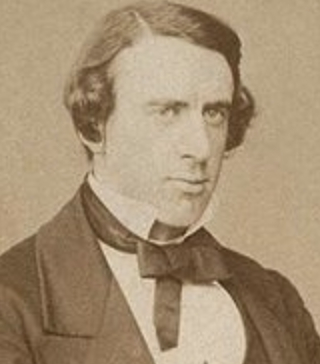

Moncure Daniel Conway

On this date in 1832, Moncure Daniel Conway was born into a conservative, pro-slavery family in Virginia. Becoming a Methodist minister at an early age, Conway soon gravitated toward Unitarianism. He graduated from Harvard Divinity School in 1854 as a Unitarian minister. Conway was much influenced by his “spiritual father,” Ralph Waldo Emerson, and abolitionist Theodore Parker.

By 1862, Conway, whose liberality had alienated his congregations, had dropped Unitarianism. He helped about 30 of his father’s slaves escape to freedom at the start of the Civil War. After embarking on an abolitionist speaking tour abroad, he was offered a position in 1863 at South Place Chapel in London, an independent and increasingly freethinking congregation. Under Conway’s tutelage, the chapel became an open-minded hub of new ideas, showcasing the day’s newsmakers and intelligentsia.

Conway, who had become an agnostic, is known for his Life of Paine (1892), the first major positive biography about the revolutionary. Conway researched and wrote other biographies, including one on Hawthorne. He also edited a four-volume edition of Paine‘s works and wrote several other books, such as Demonology and Devil Lore (1879). Conway, who had returned to America when his wife was dying, became an expatriate in Paris following his disgust with the U.S. war against Spain. (Theodore Roosevelt had even invited arch-critic Conway to join the Spanish.)

Conway completed his autobiography in 1904. When the South Place Ethical Society built its new facilities in Red Lion Square, London, in 1929, it named the building “Conway Hall.” Regular meetings are still held at Conway Hall every Sunday. Its library is adorned with portraits of freethinkers, including many of Conway. (D. 1907)

"Sunday was a day of just so much external restraint as public opinion absolutely demanded. I learned at last, as I came to be about seventeen, that my father was an entire freethinker, as much as I am now. It shocked me much, because he never taught me anything, allowed me to pick up religion from any one around me, and then scolded me because I embraced beliefs which he knew must condemn him."

— "Autobiography: Memories and Experiences of Moncure Daniel Conway" (1904)

Joel Barlow

On this date in 1754, Joel Barlow was born in Redding, Connecticut. Educated at Dartmouth College and Yale, he served as a chaplain in the Revolutionary War. His edition of The Book of Psalms, issued in 1785, was widely used by the Congregationalists. Barlow, a liberal thinker, left the ministry, took up law and was admitted to the bar in 1786. As a writer and poet he was a member of the well-known “Hartford Wits.”

Barlow became a deist after traveling in France, according to C.B. Todd (Life and Letters of J. Barlow, 1886). Barlow’s claim to freethought fame was as counsel to Algiers, when he secured the release of prisoners and negotiated the Treaty with Tripoli of 1797, which stated that the U.S. was not a Christian nation. It was written in Algiers in Arabic and signed on Nov. 4, 1796. Barlow translated the treaty, which was ratified by the U.S. Senate on May 29, 1797.

George Washington was president when the treaty was signed in Tripoli, but it was signed by John Adams. Barlow also befriended Thomas Paine and was responsible for getting Paine’s The Age of Reason published during his imprisonment in Paris. Barlow became U.S. ambassador to Napoleon’s court in 1811 and died in 1812 at age 58 in Poland while traveling to meet Napoleon during his retreat from Moscow.

“As the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion; as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion, or tranquility, of Mussulmen; and as the said States never entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mahometan nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries."

— Article 11, Treaty of Tripoli

Elihu Palmer

On this date in 1764, Elihu Palmer was born in Canterbury, Conn. Palmer graduated from Dartmouth in 1787, read theology and proved to be an unpopular minister in Presbyterian and Baptist congregations, where he spoke as a deist against the divinity of Jesus Christ. He switched to law and was admitted to the bar in Philadelphia in 1793. Yellow fever had killed his young wife and blinded Palmer.

He was invited to found the Deistical Society of New York, and lectured widely on the East Coast. He wrote orations, opinion pieces and the book Principles of Nature; or, A Development of the Moral Causes of Happiness and Misery Among the Human Species (c. 1801), in which he wrote that “the world is infinitely worse” for following Jesus.

Palmer also founded Prospect, a journal that was published from 1803-05. Unlike many deists, Palmer argued that the flawed teachings of Jesus were responsible for Christianity’s sordid history. According to Roderick C. French’s entry in Encyclopedia of Unbelief, Palmer wrote that he preferred “the correct, the elegant, the useful maxims of Confucius, Antoninus, Seneca, Price and Volney.”

When Thomas Paine was universally ostracized for writing The Age of Reason, Palmer and his second wife, who nursed Paine, remained steadfast friends. Palmer was only 42 when he died during a speaking tour. D. 1806.

"Another important doctrine of the Christian religion, is the atonement supposed to have been made by the death and sufferings of the pretended Saviour of the world; and this is grounded upon principles as regardless of justice as the doctrine of original sin. It exhibits a spectacle truly distressing to the feelings of the benevolent mind, it calls innocence and virtue into a scene of suffering, and reputed guilt, in order to destroy the injurious effects of real vice."

— Palmer, "Principles of Nature" (1801)

Abner Kneeland

On this date in 1774, Abner Kneeland was born in Massachusetts to a Congregationalist family. As a founding member of the Universalists, he served as a minister from 1804-29. When freethinker Frances Wright embarked on her famous lecture tour, becoming the first woman to speak in public in the U.S., New York City halls were closed to her. Kneeland invited her to speak from the pulpit of his Second Universalist Society in 1829, consequently lost his position and was later disfellowshipped by the church.

Kneeland’s lectures against Christianity in August 1829 were published as A Review of the Evidences of Christianity. He founded a group of freethinking New Yorkers, which met in Tammany Hall for a decade. Kneeland’s Rationalism of the Enlightenment made him a leading proponent of universal public education and the Workingmen Party.

Moving to Boston in 1830, Kneeland founded the Boston Investigator, the oldest 19th-century freethought newspaper in the U.S. His Sunday lectures to the First Society of Free Enquirers attracted crowds and the attention of influential critics. He was charged with blasphemy in 1834 for saying he did not believe in God, undergoing three trials. The prosecuting attorney for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts told the jury that if Kneeland was not punished, “marriages [will be] dissolved, prostitution made easy and safe, moral and religious restraints removed, property invaded, and the foundations of society broken up, and property made common.”

His appeal to the state Supreme Court ended with a split verdict of guilty in 1838 and he served a 60-day sentence. He moved to Iowa Territory, co-founding a freethinking settlement known as Salubria (near present-day Farmington) and becoming chair of the Van Buren County Democratic convention in 1842. An anti-infidel opposition party burned Kneeland in effigy and defeated his ticket, which was known by missionaries as “Kneelandism.”

His versatile writings included a popular spelling reader, an annotated New Testament, an edition of Voltaire‘s Philosophical Dictionary, and the two-volume The Deist (1829). D. 1844.

“Universalists believe in a god which I do not; but believe that their god, with all his moral attributes, (aside from nature itself,) is nothing more than a chimera of their own imagination.”

— Kneeland letter to Universalist editor Thomas Whittemore, Boston Investigator (Dec. 20, 1833)

Joseph Fletcher

On this date in 1905, Joseph Francis Fletcher III was born in Newark, N.J. He received a B.A. from West Virginia University before going on to receive a bachelor of divinity from Berkeley Divinity School in 1929 and a doctor of sacred theology from the University of London in 1932. He was ordained an Episcopal priest, but later renounced his belief in God and identified as a humanist.

Fletcher was a philosopher and a theologian whose work in the field of biomedical ethics was pioneering. Even when he was religious, his ethics were humanist, based on human suffering and consequences rather than biblical rules. He was an advocate for family planning, abortion, euthanasia and the sterilization of unfit parents.

He taught Christian ethics and pastoral theology at the Episcopal Theological School from 1944 to 1970, and medical ethics at the University of Virginia at Charlottesville from 1970 to 1977. He wrote several books, including Morals and Medicine (1954), Situation Ethics (1966), and Humanhood: Essays in Biomedical Ethics (1979). He was also a founding member of Planned Parenthood, the Association for Voluntary Sterilization, Society for the Right to Die and the Soviet-American Friendship Society.

In an autobiographical essay published posthumously in Memoir of an Ex-Radical, Fletcher describes his loss of faith at age 65, which he says was at first prompted by a realization that the church would never be a significant advocate in the social justice movement. He wrote: “[This realization] forced me to take a hard look at Christian doctrine itself, on its own merits: God, Jesus, revelation, sin, salvation — the whole repertory. Looking at it like that, I said to myself what I no doubt often glimpsed along the way, that the whole thing was weird and untenable.”

After this experience, Fletcher did not immediately resign from his position at the Episcopal Theology School. He called himself “an alienated or unbelieving theologian.” (D. 1991)

"[W]ith an absolute God, his word revealed and his will eternal, how could relativity in ethics get anywhere with them?"

— Fletcher explaining the outraged response from Christians, Muslims and Jews to his idea of situational ethics, ("Memoir of an Ex-Radical," 1993)

Ralph Waldo Emerson

On this date in 1803, Ralph Waldo Emerson was born in Boston. Educated at Harvard and the Cambridge Divinity School, he became a Unitarian minister in 1826 at the Second Church Unitarian. The congregation, with Christian overtones, issued communion, something Emerson refused to do. “Really, it is beyond my comprehension,” Emerson once said, when asked by a seminary professor whether he believed in God. (Quoted in 2000 Years of Freethought, ed. James A. Haught)

By 1832, after the untimely death of his first wife, Emerson cut loose from Unitarianism. During a year-long trip to Europe, he became acquainted with such intelligentsia as British writer Thomas Carlyle and the poets Wordsworth and Coleridge.

He returned to America in 1833 to a life as a poet, writer and lecturer. Emerson inspired Transcendentalism, although never adopting the label himself. He rejected traditional ideas of deity in favor of an “Over-Soul” or “Form of Good,” ideas which were considered highly heretical. His books include Nature (1836), The American Scholar (1837), Divinity School Address (1838), Essays, 2 vol. (1841, 1844), Nature, Addresses and Lectures (1849) and three volumes of poetry. Margaret Fuller became one of his “disciples,” as did Henry David Thoreau.

The best of Emerson’s rather wordy writing survives as epigrams, such as the famous: “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines.” Other one- and two-liners include: “As men’s prayers are a disease of the will, so are their creeds a disease of the intellect.” (Self-Reliance, 1841) “The most tedious of all discourses are on the subject of the Supreme Being.” (Journal, 1836) “The first and last lesson of religion is, ‘The things that are seen are temporal; the things that are not seen are eternal.’ It puts an affront upon nature.” (English Traits, 1856) “The god of the cannibals will be a cannibal, of the crusaders a crusader, and of the merchants a merchant.” (Civilization, 1862) (D. 1882)

"The dull pray; the geniuses are light mockers."

— Emerson, Representative Men" (1850)

Jean Meslier

On this date in 1664, Jean Meslier was born in Mazerny in the Ardennes, France. Meslier became the village priest in Etrépigny, where he served for 40 years. He is noted for leaving, on his deathbed in 1729, a several-hundred page manuscript titled Testament: Memoir of the Thoughts and Sentiments of Jean Meslier, which denounced Christianity and all religion, calling it the “opium of the people.” He was an early exponent of communal values and an advocate of radical equality. Though the manuscript was suppressed by the church, it was circulated illicitly.

Meslier is the originator of the quote, often attributed to Denis Diderot, that the world will be free when “the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest.” French philosopher Michel Onfray said of Meslier in his Atheist Manifesto (2005), “For the first time (but how long will it take us to acknowledge this?) in the history of ideas, a philosopher had dedicated a whole book to the question of atheism. … The history of true atheism had begun.”

Voltaire published an “extract” of Meslier’s magnum opus in 1761, selectively edited to make it seem as if Meslier was a deist like Voltaire instead of the atheist he proclaimed himself to be. The memoir was not published in its entirety until 1864. As of this writing, no full translation is known to have been completed. Despite its incompleteness, Meslier’s work was influential in the French Enlightenment and widely read by 19th-century American freethinkers. (D. 1729)

“How I suffered when I had to preach to you those pious lies that I detest in my heart. What remorse your credulity caused me! A thousand times I was on the point of breaking out publicly and opening your eyes, but a fear stronger than myself held me back, and forced me to keep silence until my death.”

— "Testament: Memoir of the Thoughts and Sentiments of Jean Meslier"

Dan Barker

On this date in 1949, Dan Barker was born in California. His father, Norman Barker, a professional trombonist, played with Hoagy Carmichael and appeared in a cameo with Judy Garland in the movie “Easter Parade.” (See Norman with Garland starting at 12 seconds in this video clip.) More is here on his family background.

His mother, Patricia, was a talented amateur singer and the family often used music in their volunteer evangelism. Barker, who became a piano player and songwriter, worked as a volunteer missionary as a teenager, going to Mexico with youth groups and becoming fluent in Spanish.

He attended Asuza Pacific College, majoring in religion. Ordained by a Christian congregation, he worked as an assistant minister in several churches but mainly freelanced with a musical ministry, also writing secular children’s music. Many of his songs and two Christian children’s musicals were produced by Manna Music and other Christian publishing houses.

In his early 30s he started a course of reading in science, liberal theology and rationalism that led to “an intense inner conflict.” Finally, “I just lost faith in faith.” In 1983, he publicly left religion. He joined the staff of the Freedom From Religion Foundation in 1987, where he has served as public relations director, becoming co-president with his wife Annie Laurie Gaylor in 2004. FFRF published his book Losing Faith in Faith (1992), as well as three freethought/humanist books for children, including Just Pretend, and more than 70 freethought songs, including “You Can’t Win with Original Sin,” “None of the Above” and “Nothing Fails Like Prayer.” He collaborated with lyricist Charles Strouse on the song, “Poor Little Me.”

Barker has recorded his songs and other traditional and contemporary freethought music on three CDs for FFRF: “Friendly Neighborhood Atheist,” “Beware of Dogma” and “Adrift on a Star.” He also freelances as a busy keyboardist and piano player in Madison, Wis., performing jazz and the Great American Songbook, much of which he has discovered was written by secular songwriters.

He has participated in more than 100 public debates with Christian clergy, religious scholars and even an imam or two. His most recent books include Godless: How an Evangelical Preacher Became One of America’s Leading Atheists, foreword by Richard Dawkins (2008); The Good Atheist: Living a Purpose-Filled Life Without God, foreword by Julia Sweeney (2011); Life Driven Purpose: How an Atheist Finds Meaning, foreword by Daniel C. Dennett (2015); GOD: The Most Unpleasant Character in All Fiction, foreword by Dawkins (2016); Free Will Explained: How Science and Philosophy Converge to Create a Beautiful Illusion (2018); and Mere Morality (2018). Barker’s books are available here.

He has appeared on many national television talk shows, including “The Daily Show,” “The Phil Donahue Show,” “Oprah,” national Fox TV, ABC’s “Good Morning America,” “Religion & Ethics News Weekly” and “60 Minutes Australia.” He has co-hosted FFRF’s radio and TV shows and is a frequent speaker on college campuses and freethought conferences. He has four children from his first marriage and a daughter with Gaylor.

"I threw out the bath water, and there was no baby there."

— Dan Barker, "Losing Faith in Faith" (1992)

Samuel Porter Putnam

On this date in 1838, Samuel Porter Putnam, the son of a Congregationalist minister, was born in New Hampshire. He became a student at Dartmouth in 1858 and enlisted as a private in the Civil War, where, after two years of service he was promoted to captain. He became a Congregationalist minister in 1868 after three years at the Chicago Theological Seminary. Three years later he broke with that denomination and joined the Unitarians. After serving in various congregations, he then “gave up all relations whatsoever with the Christian religion, and became an open and avowed Freethinker,” as he recorded in his 1894 opus Four Hundred Years of Freethought.

During the Rutherford B. Hayes administration he was appointed to the Civil Service. He left that work in 1887 to head the American Secular Union. He was elected president of the California State Liberal Union in 1891 and the Freethought Federation of America in 1892. He noted that he visited all but four of the states and territories in his work for freethought, traveling more than 100,000 miles. His other writings include: Prometheus, Gottlieb: His Life, Golden Throne, Waifs and Wanderings, Ingersoll and Jesus, Why Don’t He Lend a Hand? Adami and Heva, The New God, The Problem of the Universe, My Religious Experience, Religion a Curse, Religion a Disease, Religion a Life, and Pen Pictures of the World’s Fair.

Putnam’s tragic death created a mild scandal. He and a young lecturer colleague, May Collins, had been touring in Boston. They returned after dinner to the home where Collins was staying and were found dead the next morning in her room, victims of leaking gas. Although they were fully clothed, and there was no “evidence of impropriety,” the religious press attacked Putnam, disclosing that he was a divorced man with two children. (D. 1896)

"The last superstition of the human mind is the superstition that religion in itself is a good thing, though it might be free from dogma. I believe, however, that the religious feeling, as feeling, is wrong, and the civilized man will have nothing to do with it”

— Putnam, "My Religious Experience" (1891)

Robert Taylor

On this date in 1784, Robert Taylor (later dubbed “the Devil’s Chaplain”) was born in England and became a member of the College of Surgeons in 1807. Undergoing a religious conversion, he was ordained an Anglican priest in 1813. He lost his faith about five years later when a parishioner exposed him to rationalist writings. Resigning with a splash, he took out an advertisement seeking employment, which spelled out his loss of religion. Bowing to his mother’s pleadings, he briefly returned to the ministry but was expelled for giving deistic sermons.

In 1826 Taylor opened a deistic chapel. He flouted church authority by wearing his episcopal garments when giving his deistic lectures. That year he was sentenced to a year in jail for one of his sermons. He and oft-jailed freethought publisher Richard Carlile paired up and distributed a handbill inviting Cambridge students to hear them “present their compliments as Infidel missionaries, to … most respectfully and earnestly invite discussion on the merits of the Christian religion.” This made a deep impression on student Charles Darwin, who, in later delaying the release of his theory of evolution, took into account their treatment at the hands of Cambridge authorities.

Taylor and Carlile were thrown out of town and authorities even revoked the license of the landlord who had rented to them. After writing a pamphlet called “The Devil’s Pulpit” (1831), an energetic denunciation of New Testament dogma in which Taylor complained of “this tax-burthened and priest-ridden country,” he was nicknamed “The Devil’s Chaplain.” In 1831, he was again convicted of blasphemy, was sentenced to two years in prison and was fined £200. (D. 1844)

"[Christianity] is a system of the grossest hypocrisy, a fashionable villainy, a licensed swindle, cheat, and trick.”

“Go to church and chapel, you fools — listen to the parson, and shut your eyes, and open your mouths, and see what God will send you.”

— Taylor, "The Devil's Pulpit" (1831)

Jerry DeWitt

On this date in 1969, Jerry DeWitt was born in DeRidder, La., the progeny of a long line of Pentecostal preachers. DeWitt was an evangelical pastor of two churches in DeRidder for 25 years. His journey to atheism was gradual, doubts beginning to form when he contemplated the idea of hell. He secretly joined the Clergy Project, a confidential online community for active and former preachers who no longer hold supernatural beliefs. When a photo of DeWitt and Richard Dawkins circulated, unintentionally outing DeWitt, he embraced his status as the first “graduate” of the Clergy Project, though not without cost.

After coming out publicly as an atheist in 2011, DeWitt lost his wife, his job and many friends and relatives. Soon after he became the volunteer executive director of Recovering From Religion, serving until 2012. Speaking to Oklahoma freethinkers in 2012, he said, “Pretending has an adult word that we call faith. What religion calls faith is really pretending to believe.”

In 2013 he wrote a book about his experiences, Hope After Faith and hosted the first meeting of the Community Mission Chapel, a so-called “atheist church” in his home state. DeWitt travels to freethought gatherings around the country, deploying the oratory skills he acquired from preaching to share his story and his thoughts on “the five stages of disbelief.” “I loved God for 25 years, but yet in my search was not able to find any true evidence or proof of his existence or intervention,” he told CNN (July 22, 2013).

"Skepticism is my nature, freethought is my methodology, agnosticism is my conclusion after 25 years of being in the ministry, and atheism is my opinion."

— DeWitt, CNN interview (July 22, 2013)

Parker Pillsbury

On this date in 1809, Parker Pillsbury, the freethinker, abolitionist and reformer, was born in Massachusetts. He became a licensed minister in the Congregationalist Church in 1839 after studying at Gilmanton and Andover theological seminaries. After preaching briefly, Pillsbury left the ministry over Congregationalist and other Christian complicity with slavery. He edited The Herald of Freedom (Concord, N.H.) in the 1840s and The National Antislavery Standard in New York City in 1866.

From 1843 until 1863, Pillsbury worked as an abolitionist agent and lecturer, rubbing shoulders with most of the notable reformers of his day. Pillsbury became sympathetic to the cause of women, who had to fight to be permitted to work on equal footing with male abolitionists. After the Civil War he collaborated with Elizabeth Cady Stanton as co-editor of the newspaper The Revolution, published by Susan B. Anthony. His writings include Acts of the Anti-Slavery Apostles (1883) and the critical Church As It Is: The Forlorn Hope of Slavery (1847).

Feminist Pauline Wright Davis lauded Pillsbury for his “good deeds and unselfish work. … His pen, wherever found, has always been sharpened against wrong and injustice.” (History, 1870.) He lectured widely on the “Free Religion” circuit in Ohio and Michigan and was vice president of the New Hampshire Woman Suffrage Association. He died at age 89 in 1899.

"The Methodist Discipline provides for ‘separate Colored Conferences.’ The Episcopal church shuts out some of its own most worthy ministers from clerical recognition, on account of their color. Nearly all denominations of religionists have either a written or unwritten law to the same effect. In Boston, even, there are Evangelical churches whose pews are positively forbidden by corporate mandate from being sold to any but ‘respectable white persons.’ Our incorporated cemeteries are often, if not always, deeded in the same manner. Even our humblest village grave yards generally have either a ‘negro corner,’ or refuse colored corpses altogether; and did our power extend to heaven or hell, we should have complexional salvation and colored damnation."— Pillsbury letter, The North Star, Dec. 5, 1850

Francis Ellingwood Abbot

On this date in 1836, philosopher and theologian Francis Ellingwood Abbot was born into a family of Boston transcendentalists. Educated at Harvard and Meadville Theological School. He graduated from Harvard ranked number one in the class of 1859 and then married Katharine Fearing Loring. He became a Unitarian minister but by 1868 was forced to leave the pulpit in Dover, N.H., because his views were seen as too radical. New Hampshire’s highest court ruled in 1868 that he was “insufficiently Christian” to serve a splinter congregation in the building owned by the First Unitarian Society of Dover.

By now an avowed Darwinian, Abbot moved to Toledo, Ohio, to serve a Unitarian congregation but by 1872 it had dwindled in size to the point where members stopped paying his salary. Giving up on the pulpit, he founded the Free Religious Association and its journal The Index, a weekly paper “devoted to free religion” and “scientific theism.” He edited the paper until 1880, then founded another freethought journal, The Open Court. He taught at a boy’s school from 1881-92 in Cambridge, Mass.

Abbot wrote extensively. His books include Scientific Theism (1885), The Way Out of Agnosticism, or the Philosophy of Free Religion (1890) and The Syllogistic Philosophy, or Prolegomena to Science (two volumes, posthumously in 1906). In 1903, distraught on the 10th anniversary of his wife Katie’s death, Abbot died at age 66 on her grave in Beverly, Mass., after taking an overdose of sleeping pills. Theirs was a great love, author Brian Sullivan wrote in If Ever Two Were One: A Private Diary of Love Eternal (2005), a collection of Abbot’s correspondence and diary entries.

In 1894, a year after Katie’s death, he wrote, “[H]er soul was the violet of my home, fragrant with heaven’s own breezes, and lovely with a modest charm that kept me and keeps me her lover as in the days of yore.” (D. 1903)

“That great and growing evils render it a paramount patriotic duty on the part of American citizens, who comprehend the priceless value of pure Secular government, to take active measures for the immediate and absolute secularization of the state, and we earnestly urge them to organize without delay for this purpose.”

— Francis Ellingwood Abbot, from "Nine Demands of Liberalism," The Index (April 6, 1872)

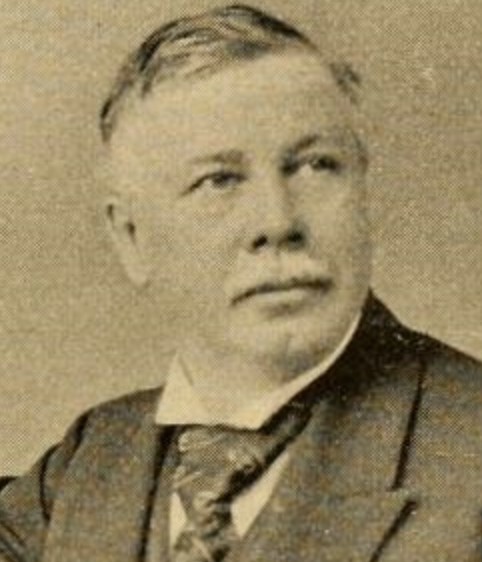

Joseph McCabe

On this date in 1867, former priest and freethought scholar Joseph McCabe was born in Macclesfield, England, to a Catholic father and Protestant mother who converted to Catholicism. As the second son in the large and poor family, he was sent at age 16 to a preparatory college at the Gorton Franciscan monastery. He was ordained a priest at age 23. As a teacher of philosophy at a Catholic school, McCabe began to doubt religion. In 1895 his moment of “no faith” came on Christmas Eve after weighing a list of pro and con arguments for belief in God (see quote below).

McCabe wrote Twelve Years in a Monastery (1897), which sold 100,000 copies. Among his 200 published books were many biographies. He also translated about 50 works, including Ernest Haeckel’s Riddle of the Universe (1902), and popularized science and history. His critiques of religion include The Rise and the Fall of the Gods (1930).

Toward the end of his life, he wrote primarily about the unholy alliance between fascism and other governments with religion in such books as The Papacy in Politics Today (1937) and A History of the Second World War (1946).

Although his acquaintances were a “who’s who” of freethinkers and reformers, McCabe’s testy personality got him expelled from the British Rationalist Association. He maintained a long-term relationship with American paperback magnate E. Haldeman-Julius, who published 121 “Little Blue Books” by McCabe and 122 larger books, earning McCabe $100,000 in royalties. McCabe lived to age 87 and requested that his epitaph read “He was a rebel to his last breath.” (D. 1955)

PHOTO: McCabe in 1910.

"I took a sheet of paper, divided it into debt and credit columns on the arguments for and against God and immortality. On Christmas Eve I wrote ‘bankrupt’ at the foot. And it was on Christmas morning 1895, after I had celebrated three Masses, while the bells of the parish church were ringing out the Christmas message of peace, that, with great pain, I found myself far out from the familiar land — homeless, aimlessly drifting. But the bells were right after all; from that hour on I have been wholly free from the nightmare of doubt that had lain on me for ten years."

— Joseph McCabe, "Twelve Years in a Monastery" (1897)

Benedict Spinoza

On this date in 1632, excommunicated rabbi and philosopher Baruch Benedict Spinoza was born in Amsterdam, Holland, the son of Portuguese immigrants named d’Espinosa who traveled to escape the Inquisition. Bertrand Russell called him “the noblest and most lovable of the great philosophers. … As a natural consequence, he was considered, during his lifetime and for a century after his death, a man of appalling wickedness.” (A History of Western Philosophy.)

Trained as a rabbi, Spinoza read Descartes and Bruno, studied Latin with a skeptic and by 24 had rejected orthodoxy. Attempts were made to bribe him to keep quiet about his doubts, followed by an assassination attempt. He changed his name from Baruch to Benedict, left Judaism and Amsterdam and resettled in The Hague in 1667. He supported himself at a poverty level by teaching and by grinding optical lenses, which worsened his health.

Meanwhile he wrote philosophical works while enduring opprobrium as an “atheist” from Christians and Jews alike, who spread scandals about him. Spinoza refused offers of help and a professorship at Heidelberg: “I do not know how to teach philosophy without becoming a disturber of established religion.” (c. 1670, Great Thoughts, edited by George Seldes.)

Spinoza was at most a pantheist, whose deism rejected immortality and free will. Tractatus Theologico-Politicus was termed by Russell to be “a curious combination of biblical criticism and political theory,” which “partially anticipates modern views.” Spinoza cautioned that the bible should be scrutinized like any other literature. He did not believe that the Pentateuch was written by Moses, that biblical miracles occurred or that Jesus was divine.

In Tractatus, Spinoza mused, “Philosophy has no end in view save truth; faith looks for nothing but obedience and piety.” Tractatuc Politicus, a political work, was Hobbesian, concurring with Hobbes that the church should be subordinate to the state. Ethics was Spinoza’s chief work, and it was published posthumously. Spinoza wrote, “Man is a social animal.” Sin, he reasoned, “cannot be conceived in a natural state, but only in a civil state, where it is decreed by common consent what is good or bad.”

He also mused, “How blest would our age be if it could witness a religion freed from all the trammels of superstition!” Spinoza, who never married, died of tuberculosis at age 44. (D. 1677)

"True virtue is life under the direction of reason."

— Spinoza, "Ethics" (1677)

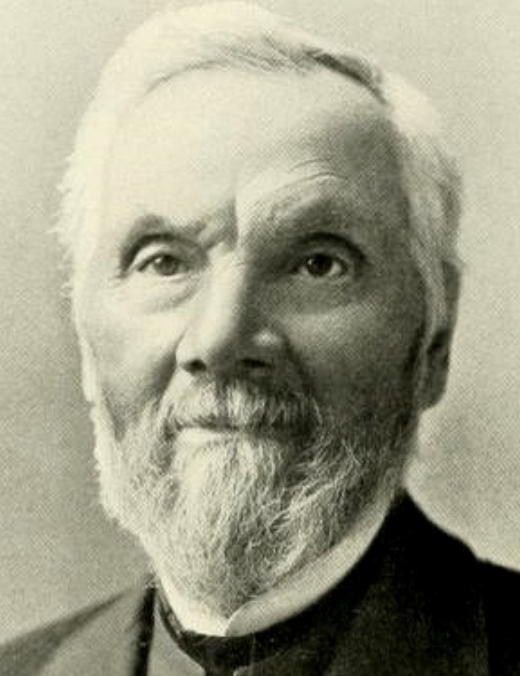

Sir Leslie Stephen

On this date in 1832, former Anglican priest, author and political essayist Leslie Stephen was born in Kensington Gore, England. He was educated at Eton, King’s College and Cambridge, primarily studying mathematics. He was required to become an Anglican priest when he became a fellow of his college but was known for his athletics, not his sermons. He later told freethought historian Joseph McCabe that Cambridge was so liberal when he was there that if it was known a dinner party was open to heretics only, it was standing room only.

By 1862 he was refusing to participate in chapel services, saying he had not lost his faith but had discovered that he had never had any. He became editor of The Cornhill in 1871, a monthly journal earlier edited by William Makepeace Thackeray, whose daughter he had married. Stephen wrote freethought articles for Fraser’s and Fortnightly. In 1877 he wrote An Agnostic’s Apology. His writings include History of English Thought in the Eighteenth Century, two volumes (1876), Johnson (1878), Pope (1880), Swift (1882), Science of Ethics (1882) and The English Utilitarians, three volumes (1900).

Stephen also edited 26 volumes of the Dictionary of National Biography and was its first editor. In 1902 he was knighted and made a fellow of the British Academy. Today he is perhaps best known as the father of Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf and as the model for Woolf’s Mr. Ramsey in To the Lighthouse (1927). (D. 1904)

"I now believe in nothing, to put it shortly; but I do not the less believe in morality."

— Stephen journal entry, Jan. 26, 1865. (Quote source: "2000 Years of Disbelief" by James A. Haught, 1996)