scholars

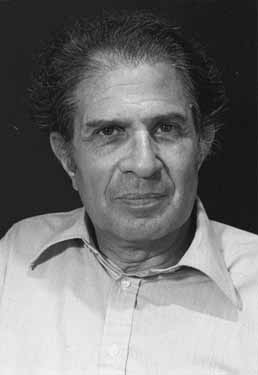

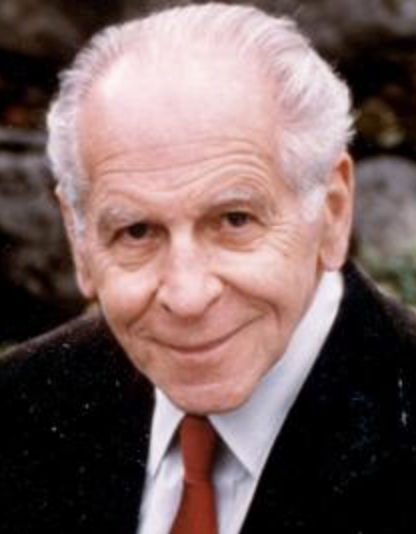

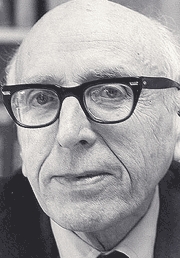

Ralph Miliband

On this date in 1924, Adolphe Miliband, later known as Ralph Miliband, was born and raised in Brussels, Belgium. His parents were Polish Jews who migrated in the 1920s to Brussels, where they met and married. The Miliband family relocated to London in 1940, fleeing the Nazi invasion. In London he changed his first name to Ralph to avoid any connotation to Adolf Hitler. At age 16 he visited the grave of Karl Marx in London to swear allegiance to “the workers’ cause.”

Miliband studied at the London School of Economics under the historian and theorist Harold Laski, who greatly influenced Miliband’s politics. Miliband broke from his studies to serve in the Royal Navy and returned to the LSE to graduate in 1947. Miliband then earned a scholarship for Ph.D. research there, at which time Laski arranged for him to teach at Roosevelt College (now Roosevelt University) in Chicago. In 1949 he became a lecturer in political science at the LSE.

Miliband co-founded the New Reasoner and New Left Review, radical journals that represented the British New Left during the 1950s. Miliband began teaching at the University of Leeds in 1972 and spent time teaching at other universities in the U.S. and Canada. He argued after the mid-1960s that a better, more revolutionary alternative to the British Labour Party needed to be established. His promotion of a Marxist style of revolutionary socialism influenced generations of socialist scholars and leaders, including Tariq Ali.

Miliband married one of his former students, Marion Kozak, in 1961. They raised their two sons in a secular lifestyle. Ironically, Miliband, who critiqued the Labour Party in his book Parliamentary Socialism (1961), had sons who rose to great power in the Labour Party. Miliband was the author of The State in Capitalist Society (1969), Marxism and Politics (1977), Capitalist Democracy in Britain (1982), Class Power and State Power (1983), Divided Societies: Class Struggle in Contemporary Capitalism (1989) and Socialism for a Skeptical Age (1994). He is buried near Marx in Highgate Cemetery in north London. (D. 1994)

“The political climate in our house was generally and loosely left: it was unthinkable that a Jew, our sort of Jew, the artisan Jewish worker, self-employed, poor, Yiddish-speaking, unassimilated, non-religious, could be anything but socialistic.”

— Miliband, in a note for his unpublished autobiography, quoted in The New Statesman, “Ralph Miliband, father of the Labour leadership rivals David and Ed, is remembered as a great teacher” (Aug. 30, 2010)

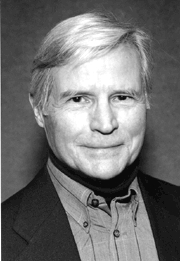

Niall Shanks

On this date in 1959, Niall Shanks was born in Cheshire, England. He earned his bachelor’s degree in philosophy from the University of Leeds in 1979, his master’s degree in philosophy from the University of Liverpool in 1981 and his Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Alberta, Canada. Shanks taught philosophy, biological sciences, physics and astronomy at East Tennessee State University (1991–2005) and at Wichita State University in Kansas (2005–11). He was especially interested in evolutionary biology and wrote several books, including Brute Science: The Dilemmas of Animal Experimentation (with Hugh LaFollette, 1997), God, the Devil, and Darwin: A Critique of Intelligent Design Theory (2004) and Animal Models in the Light of Evolution (2009).

Shanks was a self-described atheist who strongly supported evolution education. In his article “Fighting for Our Sanity in Tennessee,” published in Volume 21 of Free Inquiry magazine, he described his experience of being a nonbeliever who taught evolution in the bible belt: “I am an atheist for the same reason that I am an ‘asantaclausist.’ There is no convincing evidence to support claims about the existence of either alleged entity. Actually Santa may be the better off of the two, for the sincere testimony of small children is a tad more convincing than that of wily adults with sophistical arguments and axes to grind.”

In God, the Devil, and Darwin, Shanks denounced creation science: “The real motivations of the intelligent design movement … have little to do with science but a lot to do with politics and power — in particular, the imposition of discriminatory, conservative Christian values on our educational, legal, social and political institutions.” Shanks continued, “While we in the West readily point a finger at Islamic fundamentalism, we all too readily downplay the Christian fundamentalism in our own midst. The social and political consequences of religious fundamentalism can be enormous.”

He died in Wichita in 2011 at age 52 following a lengthy illness.

“Of God, the Devil and Darwin, we have really good scientific evidence for the existence of only Darwin.”

— Shanks, "God, the Devil, and Darwin" (2004)

Philip Appleman

On this date in 1926, Philip Dean Appleman was born in Kendallville, Ind. Appleman, a Distinguished Professor Emeritus at Indiana University, was considered the “Poet Laureate of Humanism and Freethought” and published nine volumes of poetry, three novels (two with explicitly freethinking themes) and six volumes of nonfiction. His work often skewered religious belief, including the bible. One of his most notable volumes was New and Selected Poems, 1956-1996, which included his powerful freethought poetry from the acclaimed Let There Be Light: Poems.

Appleman, a Darwin scholar and aficionado, was the editor of the widely used Norton Critical Edition, Darwin, and the Norton Critical Edition of Malthus’ Essay on Population. Appleman’s poetry and fiction have won many awards, including a fellowship in poetry from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Humanist Arts Award from the American Humanist Association, the Friend of Darwin Award from the National Center for Science Education, and the Castagnola Award from the Poetry Society of America.

His writing appeared in Harper’s Magazine, The Nation, New Republic, The New York Times, Paris Review, Partisan Review, Poetry, Sewanee Review and Yale Review. He was married for 67 years to playwright Marjorie Appleman, née Haberkorn. A great friend of FFRF, he spoke at three national conventions and was an interview guest on several broadcasts over the years. He died at age 94. Read a lovely tribute here in FFRF’s Freethought Today. (D. 2020)

O Karma, Dharma, Pudding and Pie

O Karma, Dharma, pudding and pie,

gimme a break before I die:

grant me wisdom, will, & wit,

purity, probity, pluck, & grit.

Trustworthy, helpful, friendly, kind,

gimme great abs and a steel-trap mind,

and forgive, Ye Gods, some humble advice —

these little blessings would suffice

to beget an earthly paradise:

make the bad people good —

and the good people nice;

and before our world goes over the brink,

teach the believers how to think.Last-Minute Message for a Time Capsule

I have to tell you this, whoever you are:

that on one summer morning here, the ocean

pounded in on tumbledown breakers,

a south wind, bustling along the shore,

whipped the froth into little rainbows,

and a reckless gull swept down the beach

as if to fly were everything it needed.

I thought of your hovering saucers,

looking for clues, and I wanted to write this down,

so it wouldn’t be lost forever —

that once upon a time we had

meadows here, and astonishing things,

swans and frogs and luna moths

and blue skies that could stagger your heart.

We could have had them still,

and welcomed you to earth, but

we also had the righteous ones

who worshipped the True Faith, and Holy War.

When you go home to your shining galaxy,

say that what you learned

from this dead and barren place is

to beware the righteous ones.— From “Karma, Dharma, Pudding & Pie” (2009) and "New and Selected Poems, 1956-1996"

Rebecca Newberger Goldstein

On this date in 1950, novelist and philosopher Rebecca Newberger was born in White Plains, N.Y. She was raised in an Orthodox Jewish household in White Plains and attended a Jewish high school for girls (or yeshiva) in Manhattan. Overcoming her upbringing, she “was born into consciousness” at Columbia University and received her bachelor’s degree in philosophy from Barnard College in 1972, graduating summa cum laude. She earned her Ph.D. in philosophy at Princeton in 1977.

She was a philosophy professor at Barnard, taught in the MFA writing program at Columbia and the philosophy department at Rutgers. For five years she was a visiting professor of philosophy at Trinity University in Hartford, Conn. Goldstein has been a visiting scholar at Brandeis University, a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University and a Guggenheim Fellow. She was the Miller Scholar at the Santa Fe Institute in 2011, a Franke Visiting Fellow at the Whitney Humanities Center, Yale University in 2012 and the Montgomery Fellow at Dartmouth College in 2013. She was also appointed a Visiting Professor of Philosophy at the New College of the Humanities in London, UK, in 2011 and a Visiting Professor at New York University in 2016.

In September of 2015 she was awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama. Previously she was named a MacArthur Fellow, known as the “Genius Award.” In 2005 she was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She has two daughters, Yael and Danielle, with her first husband, physicist Sheldon Goldstein. In 2007 she married Harvard psychologist and author Steven Pinker.

Her novels and nonfiction writing have received many awards. Her first novel, The Mind-Body Problem, which addresses philosophical themes, was published in 1983. Other novels include The Late-Summer Passion of a Woman of Mind; The Dark Sister, Mazel, and Properties of Light: A Novel of Love, Betrayal and Quantum Physics. Her book of short stories is called Strange Attractors. In 2005 she wrote Incompleteness: The Proof and Paradox of Kurt Godel, and in 2006, Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity, a biography of the 17th-century thinker.

In 2010 she returned to novel writing with Thirty-Six Arguments for the Existence of God: A Work of Fiction, a playful work with the timely theme of a protagonist who is author of a best-selling book on atheism. It concludes with a debunking of 36 arguments for the existence of God. In Plato at the Googleplex: Why Philosophy Won’t Just Go Away (2014), she imagines Plato’s take on the modern age with its technological wonders and argues that his philosophy is still relevant today.

In 2008 she was designated a Humanist Laureate by the International Academy of Humanism. In 2011 she was named Humanist of the Year by the American Humanist Association and a Freethought Heroine by the Freedom from Religion Foundation. Her FFRF acceptance speech, “Strong resistance to God’s existence,” is here.

LUKE FORD: “Tell me about you and God.”

REBECCA GOLDSTEIN: “I lived Orthodox for a long time. … I was torn like a character in a Russian novel. It lasted through college. I remember leaving a class on mysticism in tears because I had forsaken God. That was probably my last burst of religious passion. Then it went away and I was a happy little atheist.”— Goldstein, interview with Luke Ford at lukeford.net (April 11, 2006)

PZ Myers

On this day in 1957, biologist Paul Zachary “PZ” Myers was born. Myers is a biology professor at the University of Minnesota-Morris. His specialty is developmental biology and he is a proud proponent of science, evolution and atheism. He graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in zoology in 1979 and went on to earn his Ph.D in biology from the University of Oregon.

Before employment at UM-Morris, Myers worked at the University of Oregon, the University of Utah and Temple University. Myers studies zebrafish, spiders and cephalopods, an ink-squirting class of marine animals, most notably octopuses and squids.

“Pharyngula,” his very popular science blog, is partnered with National Geographic and has won numerous awards, including a 2005 Koufax Award for Best Expert Blog and an award from Nature. Myers was named Humanist of the Year in 2009 by the American Humanist Association, and won the International Humanist Award in 2011.

Myers makes his religious beliefs clear on Pharyngula: “If you’ve got a religious belief that withers in the face of observations of the natural world, you ought to rethink your beliefs — rethinking the world isn’t an option.” Commenting on his 2013 book The Happy Atheist, he said, “I’m an atheist swimming in a sea of superstition, surrounded by well-meaning, good people with whom I share a culture and similar concerns, and there’s only one thing I can do. I have to laugh.”

Myers at Ken Ham’s Creation Museum in Kentucky in 2009; syslfrog photo under CC 2.0.

“What I want to happen to religion in the future is this: I want it to be like bowling. It’s a hobby, something some people will enjoy, that has some virtues to it, that will have its own institutions and its traditions and its own television programming, and that families will enjoy together. It’s not something I want to ban or that should affect hiring and firing decisions, or that interferes with public policy. It will be perfectly harmless as long as we don’t elect our politicians on the basis of their bowling score, or go to war with people who play nine-pin instead of ten-pin, or use folklore about backspin to make decrees about how biology works.”

— Myers, interviewed in the 2008 documentary "Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed"

Jean Astruc

On this date in 1684, Jean Astruc was born in France, the son of a Protestant minister who converted to Catholicism. Astruc, who became a physician, was one of the early founders of bible criticism. He served as professor of anatomy at Toulouse, then Montpellier, and later as professor of medicine at Paris. In 1753 he published his Conjectures.

Astruc was among the first to try to show that the Book of Genesis was based on several sources or manuscript traditions, an approach now called the documentary hypothesis. According to historian J.M. Robertson, he died without the sacraments. (D. 1766)

—

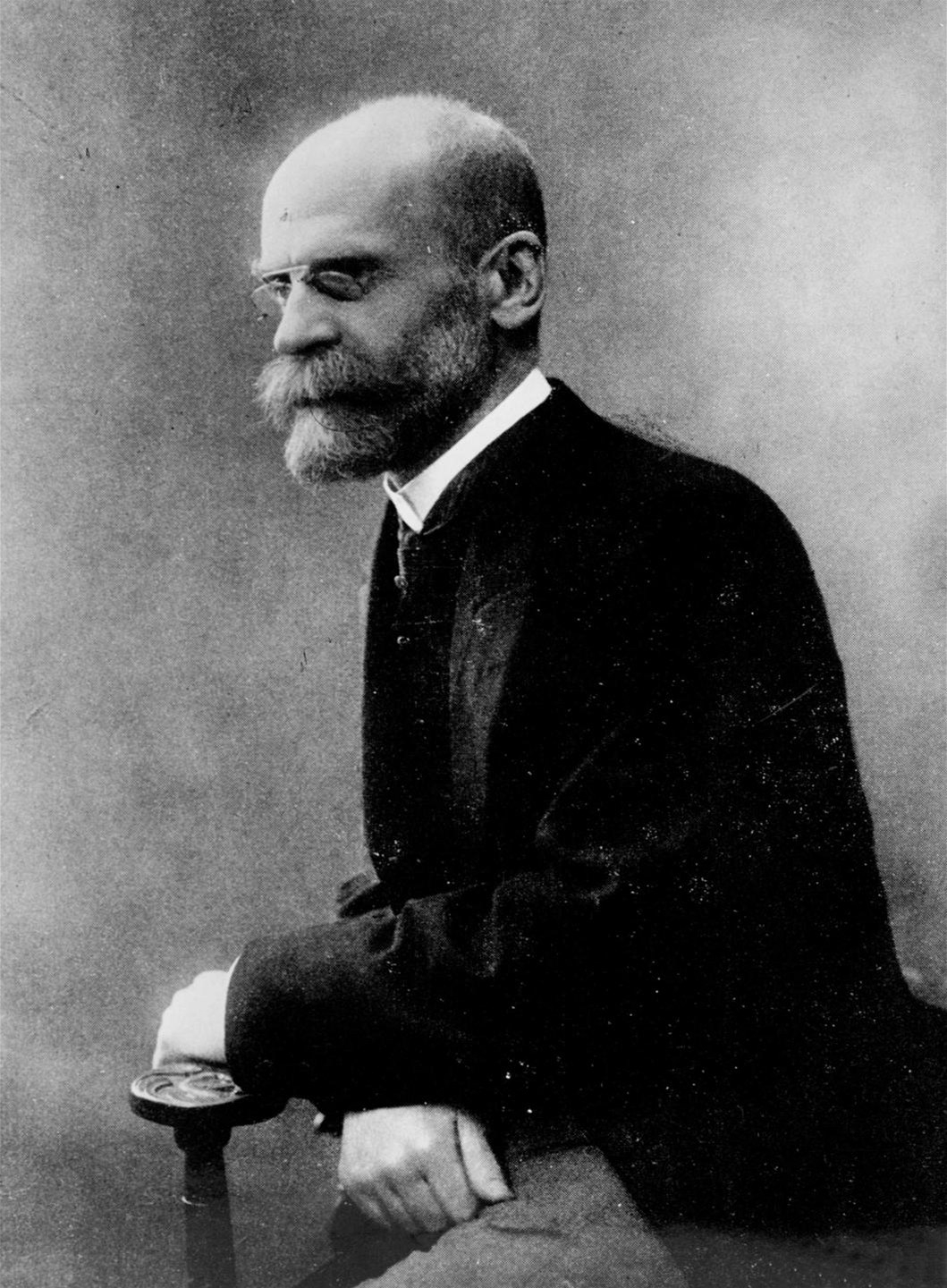

Emile Durkheim

On this date in 1858, David Emile Durkheim, one of the most significant founders of sociology, was born in Epinal in Lorraine, France. His father, grandfather and great-grandfather were prominent rabbis. Durkheim spent time in rabbinical school but broke with Judaism early in life (Emile Durkheim: An Introduction to Four Major Works by Robert Alun Jones, 1986). Durkheim excelled in school, earning his bachelor in letters and sciences in 1875, two years earlier than normal, from College d’Epinal.

He was admitted to the prestigious École Normale Supérieure in 1879 and passed examinations to become a philosophy lecturer in 1882. He was appointed to the Faculty of Letters at Bordeaux to lecture on the “Science Sociale,” marking the first time sociology officially entered the French university system. Durkheim founded the Année Sociologique in 1898, the first French social science journal, still in existence. In 1902 he was appointed chair of education at the Sorbonne in Paris. For a time, his courses were the only lectures required at the Sorbonne.

Durkheim believed religion served a unique role in human life and indeed shaped many social structures, but that its origins were in human society, not from a divine source (“Reasons people choose atheism,” BBC, Oct. 22, 2009). “Frequently described as a ‘secular pope,’ he was viewed by critics as an agent of government anti-clericalism.” (Jones, 1986) Some of his greatest contributions to sociology include The Division of Labour in Society (1893), Rules of the Sociological Method (1895), On the Normality of Crime (1895), Suicide (1897), Sociology and Its Scientific Domain (1900) and The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912). Published posthumously were other important works, including Education and Sociology (1922), Sociology and Philosophy (1924) and Pragmatism and Sociology (1955).

Overwork and the death of a beloved son in World War I in 1916 had severe repercussions on Durkheim’s health. He suffered a stroke and died at the age of 59. He is buried in Paris. (D. 1917)

“Religious force is nothing other than the collective and anonymous force of the clan.”

— Durkheim, "The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life" (1912)

Thomas Szasz

On this date in 1920, psychiatrist Thomas Szasz was born in Hungary. He earned a degree in physics from the University of Cincinnati in 1941, and his medical degree from the same university in 1944. His residency was in psychiatry. Szasz, went on to be a professor of psychiatry at the State University of New York-Syracuse and in 1990 the University made him a professor emeritus.

He was a critic of coercive psychiatry and a libertarian who supported suicide as a fundamental right. He favored abolition of the insanity defense and involuntary mental hospitalization, and refered to the “myth of mental illness.” His many books include The Manufacture of Madness, The Myth of Mental Illness, A Lexicon of Lunacy, and, with Milton Friedman, On Liberty and Drugs.

His freethought credentials included being named the 1973 Humanist of the Year by the American Humanist Association and being a Humanist Laureate with the Council for Secular Humanism. He has had a major influence on the field of psychiatry. (D. 2012)

“If you talk to God, you are praying. If God talks to you, you have schizophrenia.”

— Szasz, "The Second Sin" (1973)

Clémence Royer

On this date in 1830, Clémence-Auguste Royer (née Augustine-Clémence Audouard) was born in Nantes, France. Her parents were Catholic royalists and didn’t marry until seven years after her birth. Her early education was in a convent school. Royer became a republican following the Revolution of 1848 and started to question other commonly held views. She obtained a teaching certificate and taught at girls schools in Wales, where she mastered English, and in France.

She read widely on science in these school libraries. In 1855, as a result of her inquiries, she rejected Catholicism thoroughly and devoted herself to science. She began to offer lectures on science and logic for women in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1858.

Royer translated Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species into French in 1863. She controversially added a 60-page preface which used Darwin’s mechanism for evolution as part of an anti-religious argument, which Darwin did not make. By this time the book was in its third English edition and contained several strong references to a creator. Royer had been an evolutionist before reading Darwin, having been strongly influenced by the writings of Jean Baptiste LaMarck.

French scientists, especially atheists and anthropologists, were strongly influenced by evolution and natural selection as framed by Royer, who also discussed the implications of evolutionary theory for human beings and society in her introduction. It would be almost 10 years before Darwin himself grappled with these issues in The Descent of Man. Royer continued as Darwin’s official French translator until the third French edition of Origin was published in 1870.

Royer, despite not being a research scientist, remained a popular interpreter of science as well as a philosopher of science. As a woman, she was denied access to many learned societies, as well as university teaching positions. It has been argued by Jennifer Michael Hecht and others that Royer opened doors to women within the freethinking movement. In 1866 she had a son, René, by her lover and life partner, Pascal Duprat, a married man, which sharpened her concern about the major legal obstacles then present to unwed mothers and their children.

She published many books and articles and considered the pinnacle to be Natura rerum, her theory of nature. In 1900 she was named a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor for her contributions as “a woman of letters and a scientific writer.” Royer died in 1902 at age 71. Her son died of liver failure six months later in Indochina. (D. 1902)

“Yes, I believe in revelation, but a permanent revelation of man to himself and by himself, a rational revelation that is nothing but the result of the progress of science and of the contemporary conscience, a revelation that is always only partial and relative and that is effectuated by the acquisition of new truths and even more by the elimination of ancient errors.”

— Royer, preface to Darwin's "L'origine des espèces," cited in Jennifer Michael Hecht's "The End of the Soul" (2003)

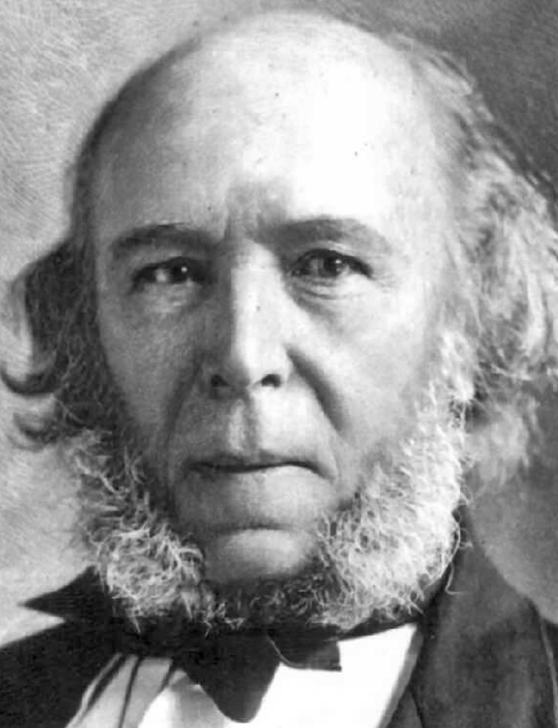

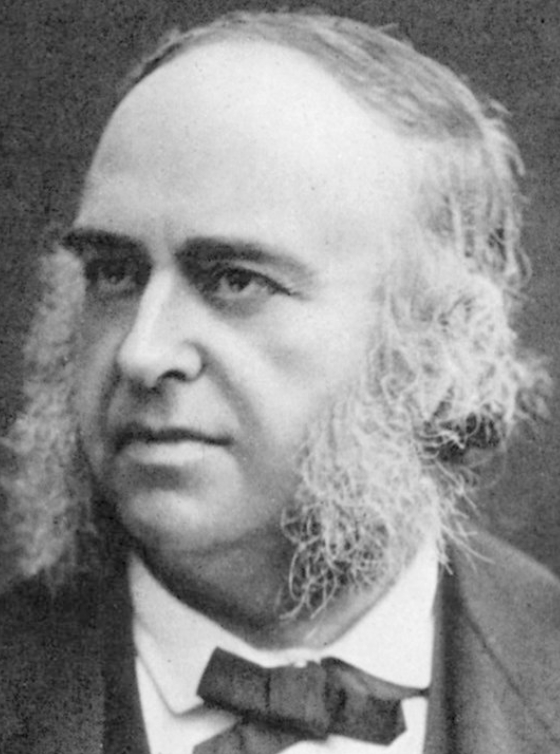

Herbert Spencer

On this date in 1820, Herbert Spencer was born in England. The agnostic philosopher was educated in engineering but worked as a journalist and writer. Spencer became good friends with leading thinkers and writers, such as Thomas Huxley and novelist George Eliot. His Principles of Psychology was published in 1855, followed by a series of major works on the principles of biology, sociology, education and ethics.

Spencer, in Social Statics (1850), wrote: “Whatever fosters militarism makes for barbarism; whatever fosters peace makes for civilization.” (D. 1903)

“Religion has been compelled by science to give up one after another of its dogmas, of those assumed cognitions which it could not substantiate.”

— Spencer, "First Principles" (1862)

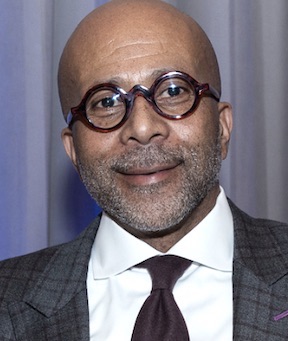

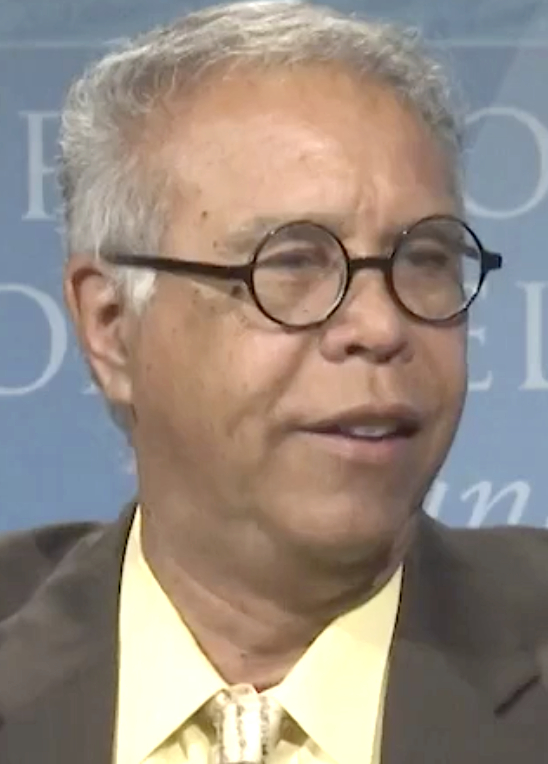

Anthony B. Pinn

On this date in 1964, humanist scholar Anthony Bernard Pinn was born to Raymond and Anne Pinn in Buffalo, N.Y. He grew up going to Baptist and African Methodist Episcopal (AME) churches and decided that he was going to be a minister. He preached his first sermon from the pulpit at age 12 and later transferred from public school to a Southern Baptist high school before enrolling at Columbia University, where he earned a B.A. He worked as an AME youth pastor in Brooklyn and Boston but started to believe that the church had no real answers to people’s problems. “I was moving from this kind of evangelical fundamentalist position to something more along the lines of the social gospel, but it still wasn’t getting it done.” (October 2014 speech at the Freedom From Religion Foundation’s national convention.)

Continuing his studies, he earned a master of divinity degree and a Ph.D. in philosophy from Harvard in 1994. His dissertation title was “ Wonder as I Wonder: An Examination of the Problem of Evil in African-American Religious Thought.” He had been questioning whether God existed and was having issues with theism more than religion. He asked himself, “Do the people matter, or is it the tradition that matters?” He relinquished his minister’s credentials, remaining interested in religion but seeing it as “a force that needed to be wrestled with and understood as a cultural development that shaped world events in some profound ways.” In his first book, Suffering and Evil in Black Theology (1995), Pinn discussed theodicy (why God permits evil) from an African-American perspective. How, he asked, can black theists, particularly black theologians, make sense of a perfect, benevolent God in light of African-American suffering?

After teaching at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, Suffolk University and Macalester College, he accepted an offer in 2003 from Rice University in Houston, becoming the first African-American to hold an endowed chair there as a professor of humanities and religion. Pinn is the founding director of the Center for Engaged Research and Collaborative Learning at Rice and director of the Institute for Humanist Studies in Washington. He’s the author, co-author or editor of more than 35 books, including the Fortress Introduction to Black Church History (with his mother, Anne H. Pinn, an AME minister, in 2001), The End of God-Talk: An African American Humanist Theology (2011), Writing God’s Obituary: How a Good Methodist Became a Better Atheist (2014), Humanism: Essays in Race, Religion, and Cultural Production (2015) and When Colorblindness Isn’t the Answer: Humanism and the Challenge of Race (2017).

His awards include the African-American Humanist Award from the Council for Secular Humanism (1999), Harvard University Humanist Association Humanist of the Year (2006) and Unitarian Universalist Humanist Association Humanist of the Year (2017). He was named a recipient in 2019 of FFRF’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award for speaking truth to power. Pinn’s research interests include humanism and hip hop culture. He married journalist Cheryl Johnson in 2000. They separated in 2005 and divorced in 2015.

PHOTO: Pinn receiving FFRF’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award; Ingrid Laas photo.

“For me the title is a way of capturing the decline and eventual death of a concept — God — that had been important to me for years. I wanted the title to reflect my transition from theism to nontheistic humanism through my push away from God — God being the central category of my religious youth.”

— Anthony Pinn, interview, Religion News Service, April 1, 2014, on his book "Writing God’s Obituary: How a Good Methodist Became a Better Atheist"

Steven Weinberg

On this date in 1933, Steven Weinberg was born in the Bronx, N.Y. He received his undergraduate degree in physics from Cornell University in 1954, which he attended on a scholarship. There he met his future wife, Louise Goldwasser. They married in 1954. She became a professor of law at the University of Texas. Weinberg began his graduate study at the Institute for Theoretical Physics in Copenhagen (now the Niels Bohr Institute). He completed his Ph.D. at Princeton in 1957.

In 1979 Weinberg was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics along with Abdus Salam and Sheldon Lee Glashow “for their contributions to the theory of the unified weak and electromagnetic interaction between elementary particles, including, inter alia, the prediction of the weak neutral current.” This was one of the most significant scientific advances in the second half of the 20th century.

He received many other awards, including the national Medal of Science in 1991. He was also a foreign member of the Royal Society of London. Known for his writing, Weinberg received the Lewis Thomas Prize, which is awarded to the researcher who best embodies “the scientist as poet.”

Weinberg wrote hundreds of scholarly articles and textbooks such as The Quantum Theory of Fields (three volumes: 1995, 1996, 2003) and Cosmology (2008); the more popular works The First Three Minutes: A Modern View of the Origin of the Universe (1977) and Dreams of a Final Theory (1993, which contains a chapter called “What About God?”). His collection Facing Up: Science and its Cultural Adversaries was published in 2001, and Lake Views: This World and the Universe in 2011.

Weinberg was outspoken about his lack of religion and encouraged other scientists to be more vocal in their opposition to religious ideas. He said, “As you learn more and more about the universe, you find you can understand more and more without any reference to supernatural intervention, so you lose interest in that possibility. Most scientists I know don’t care enough about religion even to call themselves atheists. And that, I think, is one of the great things about science — that it has made it possible for people not to be religious.” (Quoted in Natalie Angier, “Confessions of a Lonely Atheist,” The New York Times, Jan. 14, 2001)

He added, “The whole history of the last thousands of years has been a history of religious persecutions and wars, pogroms, jihads, crusades. I find it all very regrettable, to say the least.” Five years later at a forum at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego, he said: “Anything that we scientists can do to weaken the hold of religion should be done and may in the end be our greatest contribution to civilization.” (New York Times, Nov. 21, 2006)

In 1999 he became the first recipient of FFRF’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award, reserved for public figures who make known their dissent from religion. He began his acceptance speech: “I enjoy being at a meeting that doesn’t start with an invocation!” He said, “Nothing has been more important in the history of science than the work of Darwin and Wallace pointing out that not only the planets but even life can be understood in this naturalistic way.” More excerpts from his speech can be found here.

He died at age 88 at a hospital in Austin and was survived by his wife Louise and their daughter Elizabeth. (D. 2021)

“Religion is an insult to human dignity. With or without it you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion.”

— Weinberg address at the Conference on Cosmic Design, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington (April 1999)

Erwin Chemerinsky

On this date in 1953, legal scholar Erwin Chemerinsky was born to Arthur and Raeda Chemerinsky, a working-class Jewish couple from Chicago’s South Side. He earned a bachelor’s degree in communication from Northwestern University in 1975 and graduated cum laude from Harvard Law School in 1978 while working with the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau.

He taught law at DePaul University, the University of Southern California and at Duke University before becoming the founding dean of the University of California-Irvine School of Law and Raymond Pryke Professor of First Amendment Law in 2008. He married Catherine L. Fisk in 1993. She is a law professor at UC-Irvine who has degrees from the University of Wisconsin and UC-Berkeley.

Chemerinsky was elected in April 2016 to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His areas of expertise are constitutional law, federal practice, civil rights and civil liberties and appellate litigation. He’s the author of eight books, including The Case Against the Supreme Court (2014) and The Conservative Assault on the Constitution (2010) and has had over 200 articles published in top law reviews and journals.

In January 2014, National Jurist magazine named him the most influential U.S. legal educator. (He finished second to Cass Sunstein in 2015.) In 2014, FFRF named him a Champion of the First Amendment, an award he accepted at FFRF’s national convention in Los Angeles. His convention speech was titled “The Vanishing Wall Separating Church and State.”

PHOTO: Ingrid Laas

“The thesis of my remarks is a simple one: Now more than ever, we need the Freedom From Religion Foundation. In 1947 in Everson v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court held that the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment applies to state and local governments. All nine justices believed that the Establishment Clause was meant to create a wall that separates church and state. Now for the first time since 1947, a majority of the court rejects that notion. We have a Supreme Court that is hostile toward freedom from religion.”

— FFRF convention speech, Oct. 25, 2014

Paul Broca

On this date in 1824, Pierre Paul Broca was born in Sainte-Foy-la-Grande, France. He began attending medical school when he was only 17, graduated at 20 and later earned degrees in mathematics, literature and physics. Broca went on to become a professor of surgical pathology at the University of Paris and was an accomplished anatomist who advanced understanding of speech production in the brain. His most important achievement was discovering Broca’s area, a region of the brain responsible for speech production.

His work was also influential in cancer pathology and treatment of brain aneurysms. Broca founded the Anthropological Society of Paris in 1859, and his findings in anthropology often contradicted biblical teachings. Broca himself died, ironically, of a brain aneurysm. His brain was preserved after his death, becoming the inspiration for Carl Sagan’s 1974 book Broca’s Brain.

According to The End of the Soul by Jennifer Michael Hecht (2003), Broca thought that the more educated humans were, the less religious they would become. Broca also firmly supported natural selection: “Far from blushing in shame for my species because of its genealogy and parentage, I will be proud of all that evolution has accomplished.” (D. 1880)

“[Religion is] nothing more than a type of submission to authority.”

— Broca, "Bulletins de la Société d’anthropologie de Paris"

Alfred “Dilly” Knox

On this date in 1884, classics scholar and cryptographer Alfred Dillwyn “Dilly” Knox was born in Oxford, England, to Edmund Knox, an Anglican cleric and future bishop of Manchester, and Ellen (French) Knox. She died when Knox was 8. The fourth of six children, Knox was educated at Eton College and King’s College-Cambridge, where he studied classics and papyrology and was friends with Lytton Strachey and John Maynard Keynes.

When World War I broke out, he was recruited by the Royal Navy to work in its cryptology unit, which broke the code for the German “Zimmermann Note” to Mexico that helped bring the U.S. into the war. After the armistice, he completed deciphering the work of 3rd-century BCE Greek poet Herodas from papyrus fragments. He married Olive Roddam, his former secretary, in 1920. They had two sons.

He also resumed his codebreaking work, and at the start of World War II was senior cryptographer at the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park. He believed women had a greater aptitude for the work and more attention to detail than men, and thus his staff included a coterie dubbed “Dilly’s fillies.” It was here he worked with project director Alan Turing on refinement of Turing’s “bombe” device that would be instrumental in breaking encoded German “Enigma” messages and help doom the Third Reich.

Knox did not live to fully see the fruits of his labor, dying of lymphoma at age 58 after working from home for an extended period due to his illness. He received the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George for extraordinary service to the commonwealth. (D. 1943)

At King’s College, Knox became the only confirmed atheist in his family. “According to his niece [biographer Penelope Fitzgerald], Dilly became convinced that Christianity was a two-thousand-year-old swindle eliciting false fears and hopes in believers.”

— The American Scholar, Vol. 69, No. 4 (Autumn 2000), pp. 140-42

Vern Bullough

On this date in 1928, Vern Leroy Bullough was born in Salt Lake City, Utah. He earned a B.A. in history and languages from the University of Utah in 1951, an M.A. in history from the University of Chicago, a Ph.D. in the history of medicine and science from the University of Chicago in 1954 and a B.S. in nursing from California State University-Long Beach in 1981.

Bullough was a sexologist and historian, as well as a professor of nursing, sociology and history. He was Dean of the Faculty of Natural and Social Sciences at State University of New York at Buffalo and was one of the founders of the Center for Sex Research at Cal State.

Bullough received numerous awards for his work, including the prestigious Kinsey Award in 1995. He was a strong supporter of civil liberties who worked with the ACLU and the NAACP. Bullough has published and edited numerous books, many co-written with his first wife, Bonnie Uckerman Bullough, who was also a nurse and sexologist. Their collaborations include The Subordinate Sex: A History of Attitudes Toward Women (1973) and Sexual Attitudes: Myths and Realities (1995).

Bullough was co-president of the International Humanist and Ethical Union from 1994-97 and its vice president in 1997-98. He received a Distinguished Humanist Service Award from the IHEU in 1992. Bullough was an honorary associate of the Indian Rationalist Association, and also worked with the Humanist Academy. He wrote the 1994 essay “Science, Humanism, and the New Enlightenment.”

He had married Bonnie, his high school sweetheart, in 1947. They had two sons (David, 1954, and James, 1956). They expanded their family through the adoption of Steven (1958), Susan (1961) and Michael (1966). James died tragically when hit by a car in 1967 in Egypt during Bonnie’s year as a Fulbright Scholar. She died in 1996. Bullough later married Gwen Baker. He died of cancer at age 77 in Westlake Village, Calif. (D. 2006)

PHOTO: Oviatt Library, CSU-Northridge

“[Vern Bullough] will be sorely missed as one of the leading secular humanists in North America and the world.”

— Paul Kurtz, founder of the Center for Inquiry and Council for Secular Humanism, quoted on the IHEU website.

Howard Zinn

On this date in 1922, historian, author and peace activist Howard Zinn was born in New York City to Jewish immigrants. As a 17-year-old, Zinn attended a political rally in Times Square at the urging of neighborhood Communists and was knocked unconscious by police. He joined the Army Air Corps in 1943, received an Air Medal and, upon returning home, placed his medal and military papers in a folder on which he wrote “Never again.”

Zinn attended New York University and received a doctorate in history from Columbia University. He became chair of the history and social sciences department of Spelman College, the historically black college for women in segregated Atlanta, in 1956. He participated in the civil rights movement, served on the executive committee for SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) and inspired many of his students, including Alice Walker.

Fired for “insubordination” from Spelman in 1963 (for his criticism of the school’s failure to participate in the civil rights movement), Zinn took a position teaching history at Boston University, which he held until retirement in 1988.

An aggressive and early opponent of the Vietnam War (and war in general) and champion of liberal causes, Zinn’s 1967 Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal, was the first book calling for immediate withdrawal from the war with no exceptions. His A People’s History of the United States, published in 1980 with a small printing and little promotion, was a best-seller, hitting 1 million in sales by 2003. In his 1994 autobiography You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, Zinn wrote, “I wanted students to leave my classes not just better informed, but more prepared to relinquish the safety of silence, more prepared to speak up, to act against injustice wherever they saw it.”

While his publications were numerous, some of the highlights include the plays “Emma” (1976), about radical feminist and atheist Emma Goldman, “Daughter of Venus” (1985) and “Marx in Soho: A Play on History” (1999), and books such as Artists in Times of War (2003), History Matters: Conversations on History and Politics (2006), and Failure to Quit: Reflections of an Optimistic Historian (1993).

Zinn received the 1958 Albert J. Beveridge Prize from the American Historical Association for his book, LaGuardia in Congress; the 1998 Eugene V. Debs Award from the Debs Foundation; the Upton Sinclair Award in 1999; and the 1998 Lannan Literary Award. Zinn’s wife and lifetime collaborator, Roslyn, died in 2008. Zinn died of a heart attack at age 87 while swimming in a hotel pool in Santa Monica, Calif. (D. 2010)

PHOTO:Zinn at the Pathfinder Bookstore in Los Angeles in 2000. CC 4.0

“If I was promised that we could sit with Marx in some great Deli Haus in the hereafter, I might believe in it! Sure, I find inspiration in Jewish stories of hope, also in the Christian pacifism of the Berrigans, also in Taoism and Buddhism. I identify as a Jew, but not on religious grounds. Yes, I believe, as Pascal said, ‘The heart has its reasons which reason cannot know.’ There are limits to reason. There is mystery, there is passion, there is something spiritual in the arts — but it is not connected to Judaism or any other religion.”

— Tikkun magazine interview, "Howard Zinn on Fixing What's Wrong" (May 17, 2006)

C. Wright Mills

On this date in 1916, Charles Wright Mills was born in Waco, Texas. Mills grew up without friends, books or music and, at the behest of his insurance broker father, initially planned for a career in engineering. Enrolled at Texas Agricultural and Mechanical College in the mid-1930s, Mills frequently wrote for the student newspaper, often about his anger at upperclassmen taunting freshman.

When students criticized his writing for lacking “guts,” he wrote in response, “Just who are the men with guts? They are the men who have the ability and the brains to see this institution’s faults … the men who have the imagination and the intelligence to formulate their own codes; the men who have the courage and the stamina to live their own lives in spite of social pressure and isolation.”

These were less the words of an engineer and more the early musings of one of the 20th century’s great sociologists. After one year at Texas A & M, Mills transferred to the University of Texas-Austin, where he excelled in philosophy, sociology, cultural anthropology, economics and social psychology. At UT-Austin, Mills received a bachelor’s in sociology and a master’s in philosophy, while developing interest in the theories and writings of Karl Marx, Thorstein Veblen and John Dewey.

In 1939 he entered the doctoral program in sociology with a research fellowship at the University of Wisconsin. After completing his coursework in 1941, Mills joined the faculty at the University of Maryland, avoiding military service due to high blood pressure.

Mills involved himself in public affairs in Washington, D.C., and began writing for progressive magazines like The New Republic. In 1945 he joined Columbia University’s Bureau of Applied Social Research, where he attempted to combine his progressive political passions with empirical research. Mills wrote some of the most radical books of the 20th century, including New Men of Power (1948), White Collar (1951) and The Power Elite (1956), all published when the FBI and the attorney general were compiling lists of “subversives,” which put Mills in great personal and professional danger. Interested in the Cuban revolution under Fidel Castro, he visited Cuba in 1960.

Mills, who refused to identify with any political party, movement or religion, adamantly criticized what he called “cheerful robots,” or those who happily follow without questioning authority. He said, “If there is one safe prediction about religion in this society, it would seem to be that if tomorrow official spokesmen were to proclaim XYZism, next week 90 percent of religious declaration would be XYZist.” (“A Pagan Sermon to the Christian Clergy,” 1958.)

The Sociological Imagination (1959), Mills’ most lasting legacy, helped found the subfields of public and critical sociology. It called on sociologists to communicate with the general public instead of just one another and to connect people to public issues. At age 45 he suffered a fatal heart attack. (D. 1962)

“[A]re not all the television Christians in reality armchair atheists? In value and in reality they live without the God they profess; despite ten million Bibles sold each year, they are religiously illiterate.”

“According to your belief [Christian clergy], my kind of man — secular, prideful, agnostic and all the rest of it — is among the damned. I’m on my own. You’ve got your God.”

— Mills, "A Pagan Sermon to the Christian Clergy," remarks to the Board of Evangelical and Social Service, United Church of Canada (Feb. 27, 1958)

Hector Avalos

On this date in 1958, cultural anthropologist and biblical scholar Hector Avalos was born in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico. As a child, he attended the Church of God and gained some notoriety as a traveling Pentecostal evangelist before he was 10 years old and living with his grandmother in Arizona.

“We talked about sin and salvation. That you needed to be saved because Jesus died for your sins, and it will help you transform your life. We were against abortion. We were against premarital sex. We were against homosexuality. We were against rock ‘n’ roll.” He was determined to become a Christian missionary. (Iowa State Daily, Nov. 9, 2010)

After years of intense bible study to determine what was true and what wasn’t, he came to realize as a college freshman “that the arguments I made for Christianity were not the best, and that I could make just as excellent of an argument for other religions as I could for mine.” He had started studying to defeat any argument against his faith in God, but those studies led him instead to a faith in science and in family. Before long he was calling himself an atheist. (ibid., Iowa State Daily)

A diagnosis of a rare vascular disease called granulomatosis with polyangiitis and a dire prognosis that he had only two years to live forced him out of his anthropology degree program in 1978. He battled the disease and complications from it until he died 43 years later.

He returned to the University of Arizona in 1980 to complete his degree and then earned a master’s in theological studies from Harvard Divinity School and a Ph.D. in Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitic philology from Harvard. Overcoming his physical challenges, he taught anthropology and religious studies at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill before joining the faculty at Iowa State University in Ames in 1993 to teach those subjects.

Avalos founded the U.S. Latino/a studies program at ISU, where he was 1996 Professor of the Year in 1996, and founded the Atheist and Agnostic Society at ISU three years later. “Prior to ’99, the word ‘atheist’ was like a dirty word,” he told the school newspaper in 2010. “It still is, actually. People were reluctant to call themselves atheists, so they would call themselves skeptics or freethinkers.” He told the paper his courses weren’t meant to “convert” students to atheism but to show them different perspectives. “A lot of these kids come here not even knowing there are other viewpoints. That in itself is an eye-opening experience for them.”

He published 10 books, including “Fighting Words: The Origins of Religious Violence” (2005), and most recently “The Reality of Religious Violence: From Biblical to Modern Times” (2019). In 2018 he received the inaugural Hispanic American Freethinkers Lifetime Achievement Award in Washington, D.C. He was inducted into the Iowa Latino Hall of Fame in 2019.

Avalos was an FFRF member and a guest on its radio show and TV talk show “Freethought Matters” (Oct. 16, 2019). He was married twice and was survived by his wife Cynthia after dying at age 62 of cancer. (D. 2021)

“One thing led to another, and I realized that I did not believe in Christianity or that the Bible was the word of God, or that the Bible had any kind of divine origin.”

— Interview, Iowa State Daily, Nov. 9, 2010

Alexander Buchner

On this date in 1827, Alexander Karl Ludwig Buchner, German writer and younger brother of Ludwig and Georg Buchner, was born in Darmstadt, Germany. He was educated at Zurich University and taught philosophy there for a time. In 1862 he became a professor of German literature and language at Caen University in France.

He wrote extensively on English poetry and published “History of English Poetry” as well as works on Shakespeare, Byron, Thomas Chatterton and Richard Wagner. He was forced into exile in Holland in 1849 for his political views. He alluded to his own rationalist views in his exuberant support of his brother Ludwig’s scientific work. D. 1904.

“Before [his brother Ludwig’s book] “Force and Matter” what did the world at large know then of the first achievements of science? The vast majority were sunk in their blind faith in authority and the Bible.”

— Buchner, praising his brother's scientific achievement, introduction to "Last Words on Materialism and Kindred Subjects" by Ludwig Buchner (1901)

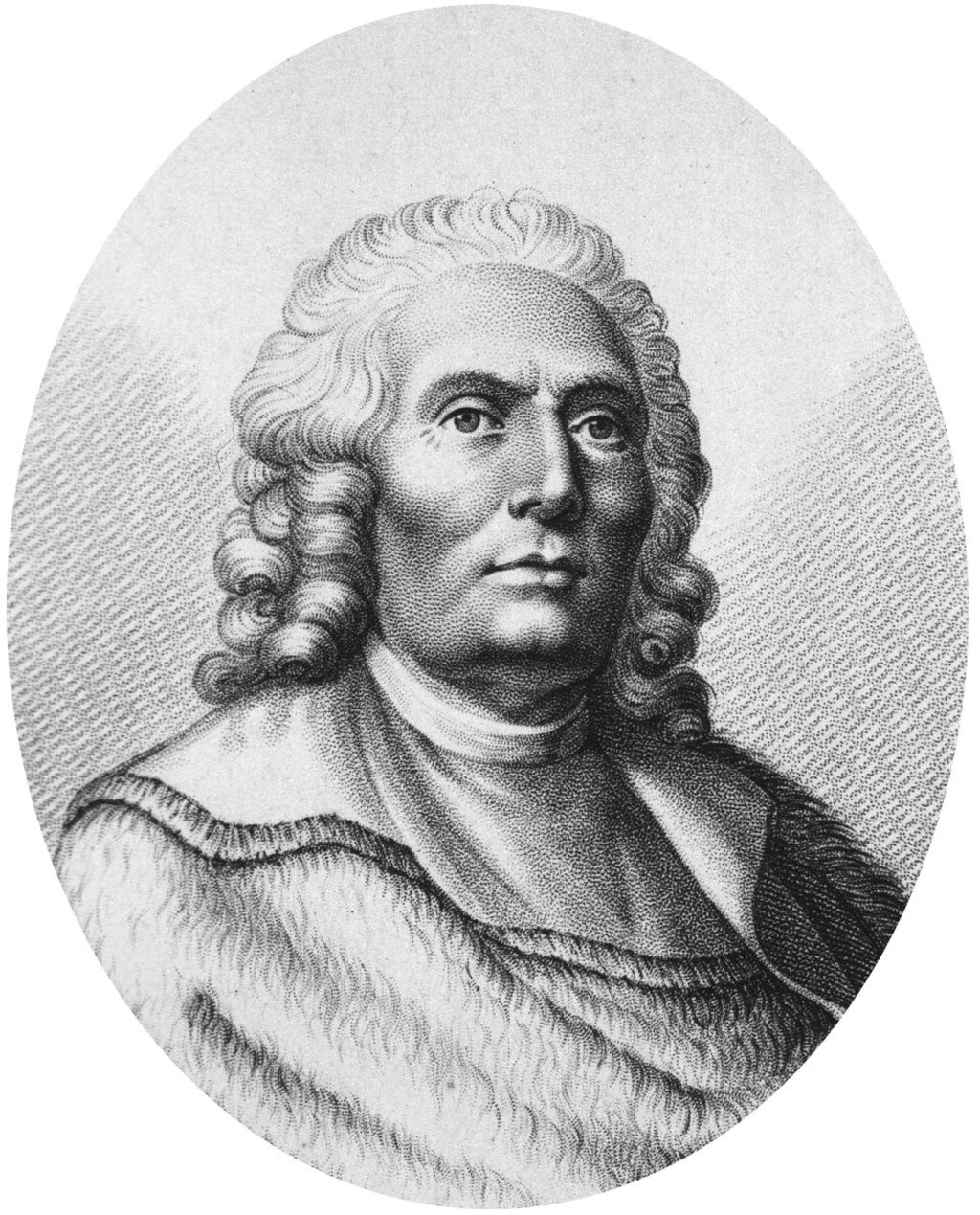

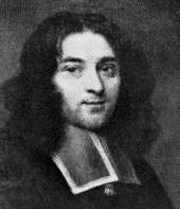

Pierre Bayle

On this date in 1647, Enlightenment skeptic Pierre Bayle, was born in southern France. He was the son of a Protestant minister at a time when Huguenots endured severe persecution. He was therefore educated at a Jesuit college in Toulouse. Under pressure he dallied with a conversion to Catholicism but ultimately rejected it, thereby becoming a “relaps” under French law — a person who becomes a heretic after abjuring heresy and subject to punishment.

Bayle decided it was safer to study philosophy in Calvinist Geneva. He became professor of philosophy in 1675 at a Protestant academy in Sedan until it was closed down by Catholic authorities in 1681. Bayle joined the community of French Protestant refugees in Rotterdam, where he taught. Bayle published a 1682 paper on a comet, including the comment, “No nations are more warlike than those which profess Christianity.”

He edited one of the first academic journals, Nouvelles de la republique des lettres (1684-87), and made rejection of superstition and intolerance a centerpiece of his writings. His masterpiece was a philosophical analysis of the words of Jesus: “Constrain them to come in.” Bayle protested conversion by force, and was the first to argue for complete religious toleration and freedom of conscience, including for Jews, Muslims and atheists.

His writings were collected in The Historical and Critical Dictionary, published in Rotterdam in 1692 and translated into English in 1736. While successful, his dictionary was banned in France and even condemned by the Huguenots. Bayle updated it to answer attacks, writing that no religious beliefs were supported by reason. Voltaire later called it “the Arsenal of the Enlightenment.” Bayle never left his Calvinist church, though many friends, future freethinkers and nearly all his critics regarded him as a “secret atheist.” He died in Rotterdam at age 59. (D. 1706)

“It is pure illusion to think that an opinion which passes down from century to century to century, from generation to generation, may not be entirely false.”

— Bayle, "Thoughts on the Comet" (1682)

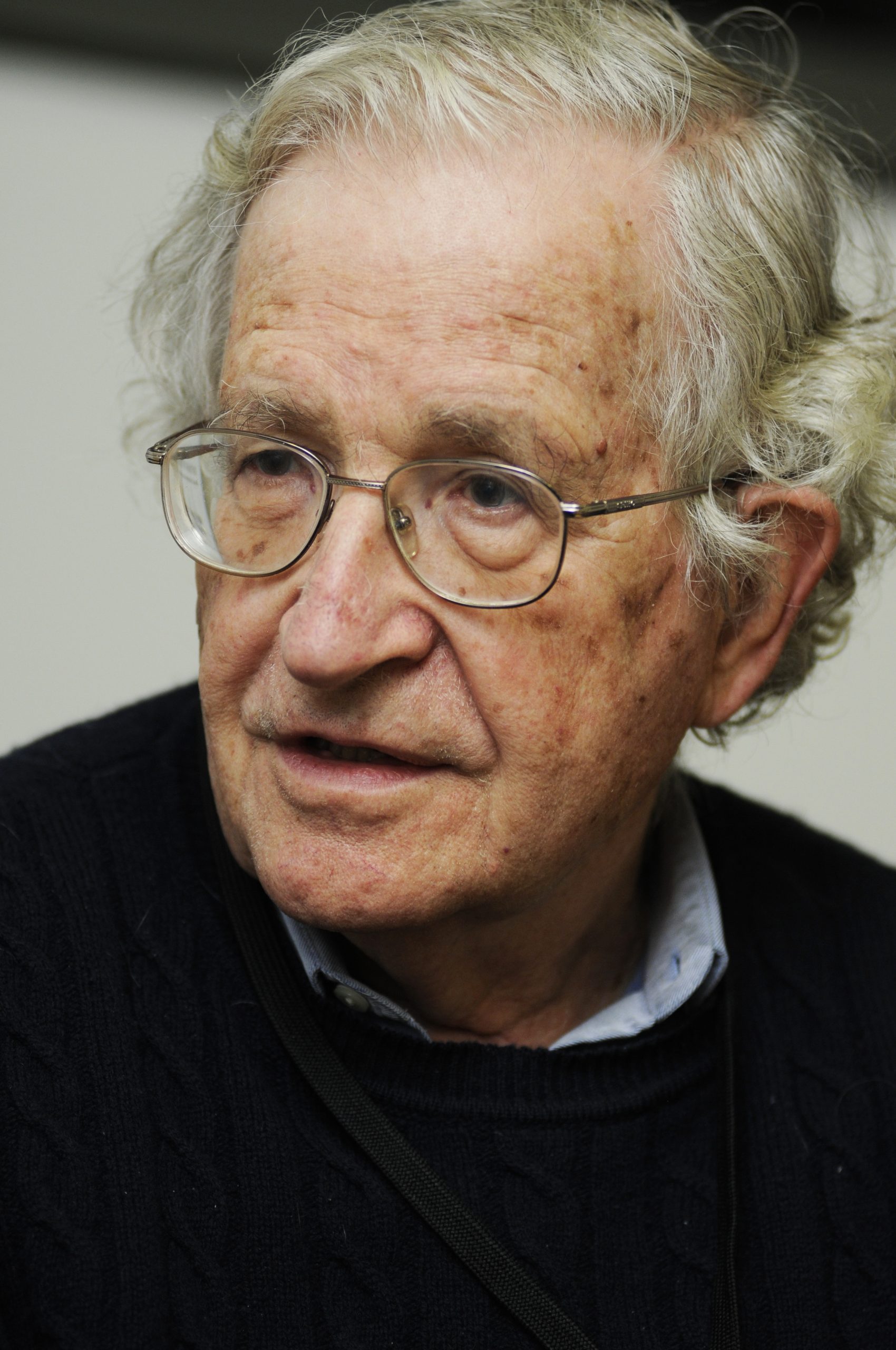

Noam Chomsky

On this date in 1928, Avram Noam Chomsky, the son of a Ukrainian immigrant Hebrew scholar, was born in Philadelphia. Although Chomsky would revolutionize the world of linguistics, politics has been close to his heart since childhood and has brought him even greater renown (and controversy). From an early age, Chomsky attended a day school that based its curriculum on the theories of John Dewey. As a teen he frequented New York City bookstores and places where Jewish intellectual men gathered. He received his B.A. (1949), M.A. (1951) and Ph.D. (1955) from the University of Pennsylvania.

He grew disenchanted as a Penn student with the structure of formal education and considered moving to a kibbutz in Palestine to promote Arab-Jewish cooperation. Then his interest in linguistics grew under the mentorship of Zellig Harris, founder of the first department of linguistics in the country, who convinced him to major in that field. Chomsky was Harris’ student from the undergraduate level, starting in 1946, through the doctoral level.

He married Carol Doris Schatz in 1949, a linguist he had known since childhood. In 1951 he was inducted into the Society of Fellows on a four-year term at Harvard University. Chomsky joined the faculty at MIT in 1955, working there in different research and academic positions for the next 60 years.

In 1957 he wrote Syntactic Structures, which revolutionized the field of linguistics and put Chomsky on the academic map. Prior to that book, most social scientists believed language and other human behaviors were learned through observation instead of being generated through more complex and innate processes.

In the 1960s Chomsky became one of the earliest and most outspoken critics of the Vietnam War. In 1967 he spent the night in jail for his involvement in the organization of a Vietnam War protest march at the Pentagon. His 1969 book, American Power and the New Mandarins, landed him on President Richard Nixon’s “enemies” list. In 1971, in Cambridge, England, Chomsky gave the Bertrand Russell Memorial Lectures, which were published as Problems of Freedom and Knowledge (1971). He has had numerous books, lectures, interviews and articles published, many of which are critical of U.S.-led atrocities in Vietnam, South and Central America, Laos and Cambodia.

His controversial book Counter-Revolutionary Violence: Bloodbaths in Fact and Propaganda (1973), co-authored with Edward S. Herman, was censored and ordered to be destroyed by its publisher, Warren Communications, because the book accused the U.S. of violence against native peoples. He continued to write monumental works on linguistics and politics, including Rules and Representations (1980), The Political Economy of Human Rights (1979), Terrorizing the Neighborhood: American Foreign Policy in the Post-Cold War Era (1991) and Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (1988), co-authored with Herman.

More recently he published Occupy (2012), a short history of the Occupy movement, Failed States: The Abuse of Power and the Assault on Democracy (2006), Gaza in Crisis (2010) and Requiem for the American Dream (2017). After his wife died in 2008, he married Valeria Wasserman in 2014. He has three children.

“I am a child of the Enlightenment. I think irrational belief is a dangerous phenomenon, and I try to consciously avoid irrational belief.”

— Chomsky, interview with David Barsamian in "Chronicles of Dissent" (1992)

Marquise du Châtelet

On this date in 1706, Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, later known as Marquise du Châtelet, was born in Paris. The daughter of the Baron de Breteuil, she showed great aptitude and was given broad latitude to study. Émilie was translating Virgil by age 16. She married Marquis Florent du Chastellet in 1725 when she was 18 and he was 34. They had three children before theirs became a marriage in name only (basically an arranged marriage in the first place), although she resisted any idea of divorce. One of their sons was imprisoned and guillotined in 1793 at age 66.

Living a social life in Paris, Émilie met Voltaire. He became her longtime companion under the eyes of her tolerant husband. Voltaire changed the spelling of her name to Châtelet. When Voltaire was facing arrest, they went to live at her husband’s country estate at Cirey, where they engaged in some of their most productive years of work and were known for working day and night. Emilie wrote treatises on mathematics, physics and philosophy.

She is best-known in France for translating Newton’s Principia, which, as the only French translation of that work, was reprinted in 1966. Her philosophical magnum opus, Institutions de Physique (Foundations of Physics), was published in 1740 and was soon translated into several other languages. Posthumously, her ideas were heavily represented in the most famous text of the French Enlightenment, the Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond D’Alembert, published shortly after her death.

Du Châtelet began an affair with the poet Jean François de Saint-Lambert in 1748 and gave birth to their daughter, Stanislas-Adélaïde, on Sept. 4, 1749. Du Châtelet died six days later from a pulmonary embolism. She was 42. Her daughter died 20 months later. Du Châtelet had dedicated her Deistic manuscript, Doubts About Revealed Religion, which was posthumously published in 1792, to Voltaire. (D. 1749)

IMAGE: Du Châtelet in a painting by Maurice Quentin de La Tour.

Leo Pfeffer

On this date in 1910, Leo Pfeffer, a leading legal proponent in the mid-20th century of separation of church and state, was born in Austria-Hungary. He came to the U.S. at age 2 with his family. He was raised a Conservative Jew and remained observant, while later quipping that “the Orthodox consider me to be the worst enemy they’ve had since Haman in the Purim story!” (See featured quote below.)

After practicing law and working as associate general counsel for the American Jewish Congress, Pfeffer became a professor of political science in 1964 at Long Island University, where he taught until his retirement in 1980. He was the American Humanist Association’s Humanist of the Year in 1988.

His masterpiece, Church, State, and Freedom (1953), is the ultimate sourcebook for the history of the evolution of the principle of the separation of church and state. His eight books include The Liberties of an American: The Supreme Court Speaks (1956), Religious Freedom (1977) and Religion, State & the Burger Court (1985). Pfeffer called himself a “strict separationist in contrast to what is called ‘accommodationist.’ ”

Pfeffer pleaded “partly guilty” to inadvertently perpetuating the myth that “secular humanism” is a religion. In defending nontheist Roy Torcaso before the U.S. Supreme Court in Torcaso’s case challenging a religious test in Maryland to become a notary public, Pfeffer wrote that “there are religions which are not based on the existence of a personal deity.” His examples: Ethical Culturists, Buddhists and Confucians.

“My good friend Justice Black thought that wasn’t good enough. He put in the secular humanists. Who told him secular humanism? I didn’t have it in my brief! I couldn’t sue, because you can’t sue a justice of the Supreme Court. But since then I rued the day.” (Freethought Today, Jan/Feb 1986)

He married Freda Plotkin in 1937. They had two children, Alan Israel and Susan Beth. (D. 1993)

“I believe that the history of the First Amendment and also the Constitution itself, which forbids religious tests for public office, have testified to the healthful endurance of a principle which is the greatest treasure the United States has given the world: the principle of complete separation of church and state. I’m here to tell you that that principle is endangered today. ”

— Pfeffer speech to FFRF's national convention in Minneapolis (Sept. 29, 1985)