scientists

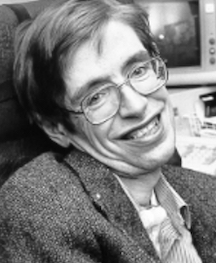

Stephen Hawking

On this date in 1942, cosmologist Stephen Hawking was born in Oxford, England, “300 years after the death of Galileo,” as he once noted. He attended Oxford, studying physics, then earned his Ph.D. in cosmology at Cambridge. By his 21st birthday he had been diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig’s disease).

Despite his disability, which confined him to a wheelchair and forced him to rely on mechanized speech, Hawking became a research fellow, worked at the Institute of Astronomy, and in 1973 joined the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics at Cambridge.

Hawking is celebrated for his work on unifying General Relativity with Quantum Theory. His popular science books include A Brief History of Time, Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays and The Universe in a Nutshell. Although some rationalists have been disappointed in his tendency to use the term “god” too loosely as a metaphor, Hawking made it clear he did not believe in a personal god.

In an interview with Diane Sawyer on ABC News (June 7, 2010), Hawking said, “There is a fundamental difference between religion, which is based on authority, [and] science, which is based on observation and reason. Science will win because it works.”

In his follow-up book The Grand Design (2010), Hawking and co-author Caltech physicist Leonard Mlodinow wrote that “God” is not necessary: “Because there is a law such as gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing. Spontaneous creation is the reason there is something rather than nothing, why the universe exists, why we exist. It is not necessary to invoke God to light the blue touch paper and set the universe going.”

In an interview with the Spanish newspaper El Mundo (Nov. 6, 2015), Hawking was more forthright about declaring his atheism: “Before we understand science, it is natural to believe that God created the universe. But now science offers a more convincing explanation. What I meant by ‘we would know the mind of God’ is, we would know everything that God would know, if there were a God, which there isn’t. I’m an atheist (Soy ateo).”

In his last book, Brief Answers to the Big Questions, published posthumously in 2018, Hawking wrote, “There is no God. No one directs the universe.” Included in his parting advice: “Remember to look up at the stars and not down at your feet. Try to make sense of what you see and wonder about what makes the universe exist. Be curious. And however difficult life may seem, there is always something you can do and succeed at.”

Hawking met Jane Wilde in 1962, the year before his motor neuron diagnosis. They married in 1965 and had three children: Robert (1967), Lucy (1969) and Timothy (1979). His poor health and her strong Christian beliefs led to their divorce in 1995, after which he soon married Elaine Mason, one of his nurses.

After their divorce in 2006, Hawking resumed closer relationships with Jane and his children. Her book Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen was published in 2007 and was made into a film, “The Theory of Everything,” in 2014.

Hawking died at his home in Cambridge at age 76 and his ashes were interred in Westminster Abbey’s nave between the graves of Sir Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin. (D. 2018)

PHOTO: Hawking at NASA’s StarChild Learning Center, c. 1980s

“All that my work has shown is that you don’t have to say that the way the universe began was the personal whim of God.”

— Hawking, "Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays" (1993)

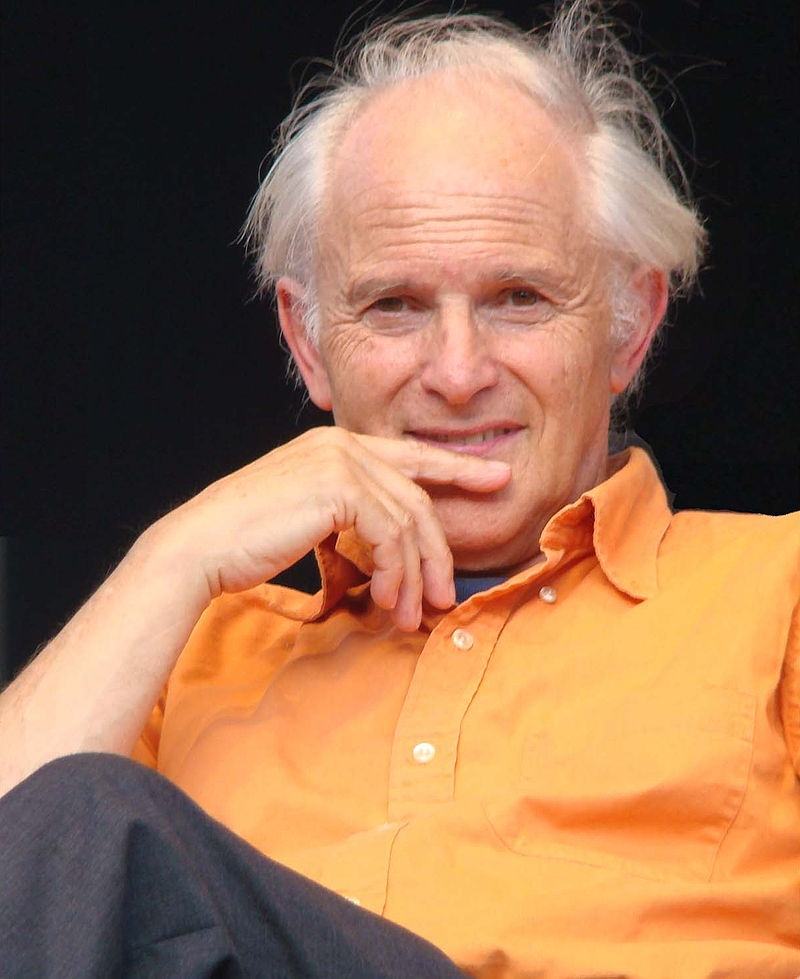

Garrett Lisi

On this date in 1968, Antony Garrett Lisi was born in Los Angeles. He earned B.S. degrees in physics and mathematics from the University of California at Los Angeles in 1991 and received his Ph.D. in physics from the University of California at San Diego in 1999. After graduation he moved to Hawaii and worked as a snowboard instructor and hiking guide. Lisi briefly taught at the University of Hawaii at Maui in 2005 before deciding to pursue independent research.

He authored the paper “An Exceptionally Simple Theory of Everything,” published on the online database arXiv on Nov. 6, 2007. The Theory of Everything, also called the E8 Theory, unites the electromagnetic force, strong force and weak force, as well as gravity and all elementary particles, through the use of the mathematical structure E8. It is an alternative to the popular string theory, which purports that these forces and particles are united by a complex system of vibrating strings.

The New Yorker called Lisi a “committed atheist” in its issue of July 21, 2008. In 2011 and 2012 he co-hosted “Invention USA,” a History channel documentary series. He lives with his longtime girlfriend, Crystal Baranyk, an artist.

PHOTO: By Cjean42 of Lisi being interviewed in Los Angeles in 2011. CC 3.0

“Lisi, an atheist, says the whole notion of God misses the point. He’s not after the creator of the universe — he’s after the universe itself. Everything.”

— Lisi profile, Maui Time (Feb. 16, 2011)

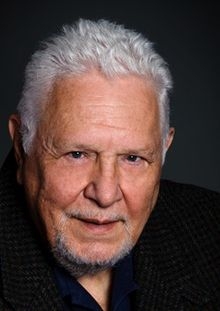

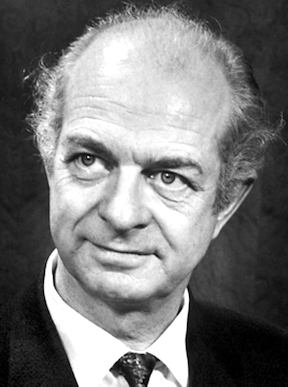

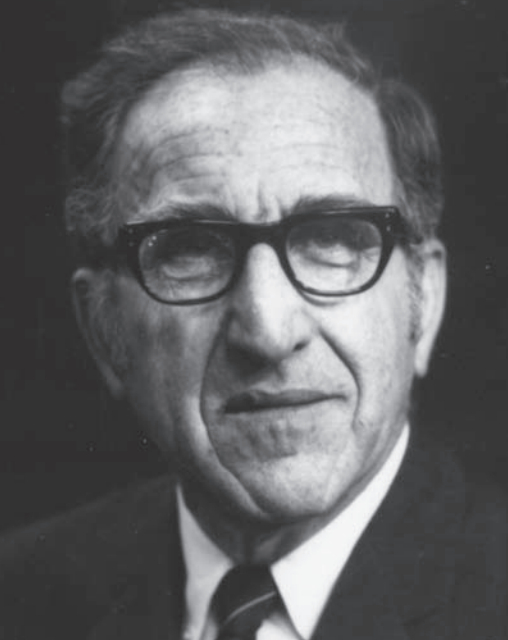

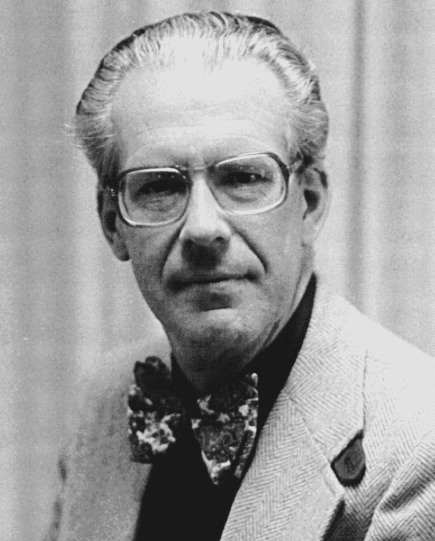

Victor Stenger

On this date in 1935, particle physicist, author and skeptic Victor John Stenger was born in Bayonne, New Jersey. Stenger, the son of a first-generation Lithuanian immigrant and a second-generation Hungarian immigrant, grew up in a Catholic neighborhood. He earned a bachelor’s in electrical engineering from Newark College of Engineering and a master’s in physics from UCLA, followed by a Ph.D. After taking a position on the University of Hawaii faculty, Stenger began a long and influential career during one of the most exciting times for physics in history.

His experiments helped establish standard models in physics, examining and uncovering the properties of quarks, gluons, neutrinos and “strange” particles. Stenger also made contributions to the emerging fields of high-energy gamma ray and neutrino astronomy. In his last major research endeavor before retiring in Colorado in 2000, Stenger collaborated on a project in Japan that demonstrated for the first time that the neutrino has mass. The project’s head researcher won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2002.

In addition to his numerous and influential peer-reviewed articles, Stenger wrote 12 books, including the 2007 bestseller God: The Failed Hypothesis: How Science Shows that God Does Not Exist. Some of his other titles include Not By Design: The Origin of the Universe (1988), The Unconscious Quantum: Metaphysics in Modern Physics and Cosmology (1995), The New Atheism: Taking a Stand for Science and Reason (2009), The Fallacy of Fine-Tuning: Why the Universe Is Not Designed for Us (2011), and God and the Folly of Faith: The Fundamental Incompatibility of Religion and Science and Why It Matters (2012).

Stenger’s work hinged on the interplay between philosophy, particle physics, quantum mechanics and religion. He was a self-professed skeptic and atheist, maintaining that all things in existence — including consciousness and the subjective illusion of libertarian free will — may be revealed and described by rational scientific inquiry without resorting to supernatural explanations, the meaning of which are empty, useless, unproductive and put a crippling end to intellectual progress.

In order to champion these causes, Stenger pursued public speaking, debating prominent Christian apologists and participating in the 2008 “Origins Conference” hosted by the Skeptics Society. Stenger was a member of a number of skeptics and humanist organizations, including presidential stints with the Hawaiian Humanists from 1990-94 and the Colorado Citizens for Science from 2002-06.

He was an honorary director of FFRF, a member of the Society of Humanist Philosophers and the Free Inquiry editorial board, and a fellow of the Center for Inquiry and the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Among a number of visiting positions, Stenger was an adjunct professor of philosophy at the University of Colorado and an emeritus professor of physics at the University of Hawaii. Stenger lived with his wife Phylliss, whom he married in 1962. They had two children. (D. 2014)

PHOTO: Licensed under CC BY 3.0.

“Science flies you to the moon. Religion flies you into buildings.”

— Stenger, who suggested this slogan post-9/11 after ideas for bus signs were solicited by the Richard Dawkins Foundation.

Jacques Monod

On this date in 1910, French biologist and Nobel Prize winner Jacques Lucien Monod was born in Paris to an American mother (Charlotte MacGregor Todd from Milwaukee) and a French Huguenot father, Lucien Monod, who was a painter and inspired him artistically and intellectually. In his doctoral work at the Sorbonne, Monod coined the term diauxie, meaning two growth phases, to describe different growth patterns he observed in bacteria. Monod is most famous for discovering, along with Francois Jacob and Andre Lwoff, the Lac operon feedback mechanism in living cells.

Monod received the 1963 Legion d’honneur, the highest decoration in France, for the operon theory of genetic control. The 1965 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded jointly to Monod, Jacob and Lwoff “for their discoveries concerning genetic control of enzyme and virus synthesis,” according to the Nobel Foundation website. Monod was among the first to suggest the existence of messenger RNA molecules. He’s considered one of the founders of molecular biology.

In addition to his scientific work, Monod was a talented musician and wrote on the philosophy of science. In his 1971 book, Chance and Necessity, he expounded on “an entirely non-providential view of the biological world as the mere product of chance and necessity, and proposed that the natural sciences reveal a purposeless world which entirely undercuts the tradition claims of religions.” (Cambridge University website, “Investigating Atheism.”)

In 1938 Monod married Odette Bruhl, an archaeologist and curator of the Guimet Museum in Paris. Their twin sons became a geologist and a physicist. He died of leukemia at age 66 and is buried in Cannes on the French Riviera. (D. 1976)

“As nontheists, we begin with humans not God, nature not deity.”

— Humanist Manifesto II (1973), of which Monod was one of the signatories when he was at the Institut Pasteur.

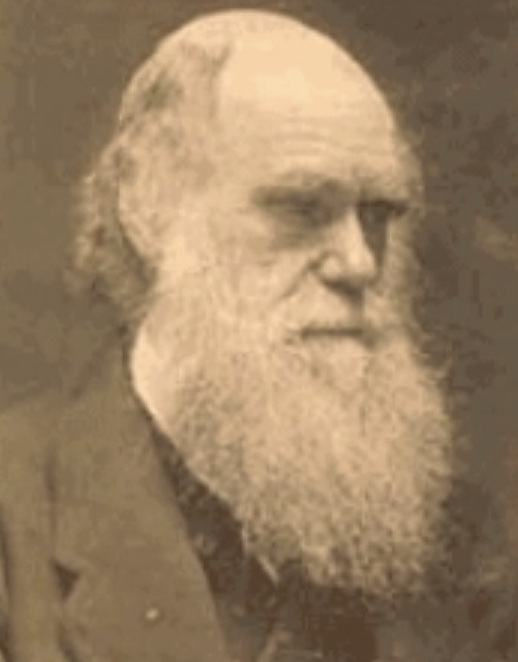

Charles Darwin

On this date in 1809, Charles Robert Darwin was born in England. He prepared for the Church at Cambridge, but his passion was natural history. During his work as a naturalist for nearly five years, starting in 1831 when he was 22, on the HMS Beagle, he began documenting and formulating his theory of evolution.

At the time he published his monumental On the Origin of Species (1859), he still accepted the “First Cause” argument. Gradually he threw off his religious beliefs. In his Descent of Man (1871), Darwin wrote: “Many existing superstitions are the remnants of former false religious beliefs. The highest form of religion — the grand idea of God hating sin and loving righteousness — was unknown during primeval times.”

He wrote the Rev. J. Fordyce on July 7, 1879, that “an agnostic would be the most correct description of my state of mind.” Darwin penned his memoirs between the ages of 67 and 73, finishing the main text in 1876. These memoirs were published posthumously in 1887 by his family under the title Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, with his hardest-hitting views on religion excised. Only in 1958 did Darwin’s granddaughter Nora Barlow publish his Autobiography with original omissions restored (see excerpt below). (D. 1882)

“I can indeed hardly see how anyone ought to wish Christianity to be true; for if so the plain language of the text seems to show that the men who do not believe, and this would include my Father, Brother, and almost all my best friends, will be everlastingly punished. And this is a damnable doctrine.”

— "The Autobiography of Charles Darwin" (1887)

Galileo Galilei

On this date in 1564, Galileo Galilei was born in Pisa, Italy. Galileo was appointed professor of mathematics at the University of Padua, where he lectured for 18 years. Galileo pioneered the experimental scientific method, building a thermoscope, constructing a geometrical and military compass and building an improved telescope. His observations of the satellites of Jupiter, sunspots, mountains and valleys on the moon made him a celebrity, but his Copernican views were investigated and condemned by the Catholic Church.

Diplomatically seeking church permission, he published “The Assayer,” (1623) describing his scientific method, which was tactfully dedicated to Pope Urban VIII. It took Galileo nearly two years to persuade the church to permit him to publish “Dialogue on the two Chief Systems of the World — Ptolemaic and Copernican” (1632), in which he wrote about impetus, momentum and gravity. The Holy Office banned the book, summoning the frail scientist to Rome for trial. Galileo was ordered to retract his theory and was condemned to house arrest for the rest of his life. Three hundred and fifty years after his death, the Catholic Church “forgave” Galileo. D. 1642.

“I have been … suspected of heresy, that is, of having held and believed that the Sun is the center of the universe and immovable, and that the earth is not the center of the same, and that it does move. … I abjure with a sincere heart and unfeigned faith, I curse and detest the said errors and heresies, and generally all and every error and sect contrary to the Holy Catholic Church.”

— Galilei's "Recantation" (June 22, 1633)

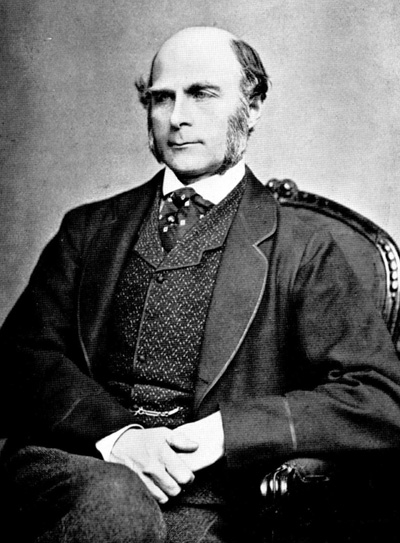

Sir Francis Galton

On this date in 1822, Sir Francis Galton was born in Birmingham, England. The grandson of Erasmus Darwin and cousin of Charles, he was educated in mathematics at Cambridge. An inheritance in 1844 left him free to travel widely. He became a famous explorer, writing several books about his travels in Syria, Egypt and southwest Africa.

In 1863 he became general secretary of the British Association and published a book on weather mapping. His Hereditary Genius was published in 1865. Galton coined the term “eugenics,” defining it very differently from its current meaning. Galton founded a eugenics research fellowship and chair at University College. He also coined the term “nature versus nurture.” His study “Statistical Inquiries into the Efficacy of Prayer” was published in the Aug. 1, 1872, issue of Fortnightly View.

Galton charmingly showed how royalty, the most-prayed-for people in the world, “are literally the shortest lived” of the affluent. Galton observed: “It is a common week-day opinion of the world that praying people are not practical.” He made scholarly contributions to fields as diverse as fingerprinting and psychology. (D. 1911)

“Your book drove away the constraint of my old superstition, as if it had been a nightmare.”

— Galton letter to Charles Darwin, recorded in "Life and Letters of F. Galton" (1914)

Svante August Arrhenius

On this date in 1859, physical chemist and Nobel Prize winner Svante August Arrhenius was born in Sweden. He studied at Upsala University, then under a professor in Stockholm. His 1884 thesis, on the galvanic conductivity of electrolyes, won him the first docentship at Uppsala in physical chemistry, a new branch of science. Arrhenius was also awarded a traveling fellowship and worked with scientists throughout Europe.

He was appointed a physics lecturer in 1891 at Stockholm University College. Arrhenius in 1896 was the first to identify the relationship between the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and global temperatures, with a rise in the percentage of carbon dioxide tied to a rise in temperature. His work played an important role in the emergence of modern climate science.

He won the Nobel Prize for chemical research in 1903 for originating the theory of electrolytic dissociation, or ionization. He also investigated osmosis, toxins and antitoxins. He was offered the position of chief of the Nobel Institute for Physical Chemistry, founded just for him.

Arrhenius wrote classic textbooks in his field, which were translated into many languages, and popularized science for the general public with such books as The Destinies of the Stars (1919). His wide interests in science were exemplified by his contributions to the understanding of such phenomena as the Northern Lights. In 1914 he was awarded the Faraday Medal of the Chemical Society.

During World War I he worked to get the release of many German and Austrian scientists who had been made prisoners of war. According to freethought historian Joseph McCabe, Arrhenius was a monist. However, Gordon Stein in The Encyclopedia of Unbelief (1988) said he was “a declared atheist.”

He was married twice, first to his former pupil Sofia Rudbeck (1894-96), with whom he had a son, Olof, and then to Maria Johansson (1905-27), with whom he had two daughters and a son. (D. 1927)

Linus Pauling

On this date in 1901, scientist and peace activist Linus Carl Pauling was born in Portland, Ore, to Herman and Lucy (Darling) Pauling. His parents, of German Lutheran background, weren’t especially active in church affairs. His father died when Pauling was 9. He studied chemistry at Oregon Agricultural College, where he met his future wife, Ava Helen Miller, with whom he would have four children. In 1922 he enrolled at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), where he earned a Ph.D. in chemistry and then joined the faculty.

He would go on to become the only person to receive two unshared Nobel Prizes: Chemistry (1954) and Peace (1962) and is considered a founding father of quantum chemistry and molecular biology. His crowning achievement was to explain the carbon bonding in molecules such as methane. He later taught at the University of California-San Diego and at Stanford University.

The advent of the nuclear age turned the Paulings into peace activists who traveled and spoke widely. They eventually joined the Unitarian Church but Pauling was not interested in theology. On “The Phil Donahue Show” in 1967, Donahue asked him if he believed in God. Pauling replied, “No, I do not.”

In accepting the Nobel Prize for Peace for 1962, he said, “The only sane policy for the world is that of abolishing war.” The award recognized his six-year campaign to persuade the U.S., Great Britain and the Soviet Union to sign a nuclear test ban. Minimizing suffering was the key to ethics, he believed. He was named Humanist of the Year by the American Humanist Association in 1961.

He died of prostate cancer at age 93 at home in Big Sur, Calif. (D. 1994)

“I am not, however, militant in my atheism. The great English theoretical physicist Paul Dirac is a militant atheist. I suppose he is interested in arguing about the existence of God. I am not.”

— Pauling, quoted in "A Lifelong Quest for Peace: A Dialogue" by Daisaku Ikeda (1992)

Gerald H.F. Gardner

On this date in 1926, mathematician Gerald Henry Frazier Gardner was born in Tullamore, Ireland. He studied mathematics and theoretical physics at Dublin’s Trinity College. He earned a master’s in applied mathematics from Carnegie Institute of Technology (1949) and a doctorate in mathematical physics from Princeton (1953). Gardner worked in applied seismology for several decades and taught at Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University), Rice University and the University of Houston.

Gardner actively pursued equal rights for women. Along with his wife, the former Jo Ann Evans, he was an early member of the Pittsburgh chapter of the National Organization for Women. Evans, a Ph.D. experimental psychologist, adopted the surname Evansgardner when they married in 1950.

Gardner and the chapter in 1969 challenged sex-based employment ads in the Pittsburgh Press. Employment want ads used to list separate categories for “Male Wanted” and “Female Wanted,” which barred women from much professional work. Gardner specifically provided statistical analysis of the likelihood of women finding employment in such a structure. This led to a landmark women’s rights decision in 1973 by the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld a Pittsburgh ordinance that prohibited sex-based employment advertisements.

As a result, want ads were “desexregated” around the nation, a huge boon for women’s employment rights. Gardner contributed statistical analysis in other cases involving gender and race discrimination and considered this work the most important of his life (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 27, 2009.) He and his wife were Life Members who joined FFRF in the late 1970s and left a generous bequest. Gardner died of leukemia at age 83 in 2009. Jo Ann died in 2010.

He “was an activist atheist, a proselytizing atheist. He thought that not saying you were an atheist hurt the cause of reality.”

— Jo Ann Evansgardner, remembering her husband in his New York Times obituary (July 28, 2009)

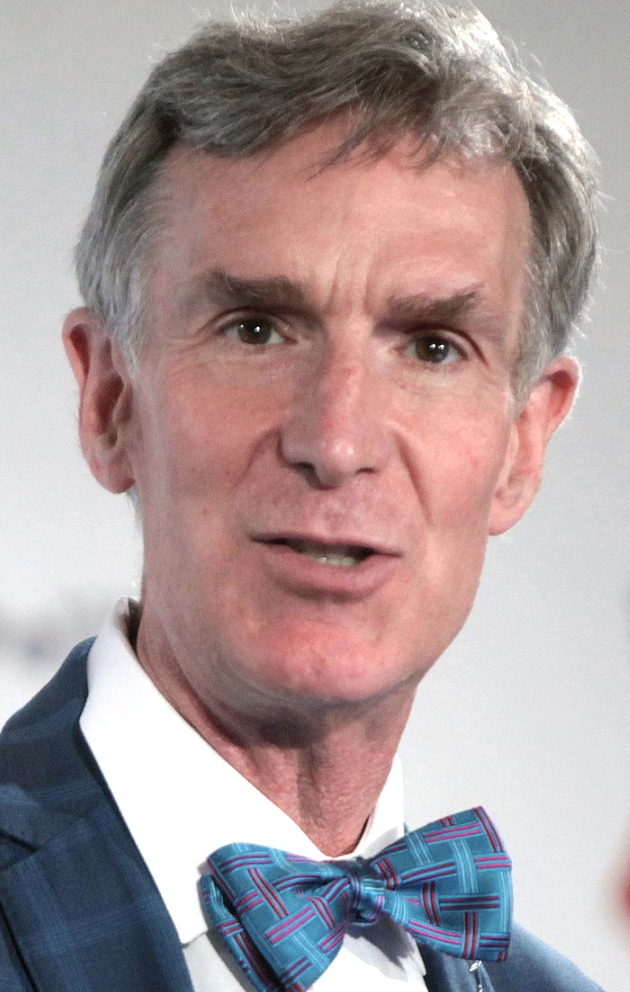

Brian Cox

On this date in 1968, Brian Edward Cox was born in Lancashire, England. After completing his secondary education, Cox joined the rock band Dare as a keyboardist. Following the band’s breakup, Cox enrolled at the University of Manchester to study physics. He continued his career in music, playing with the pop band D:Ream, while receiving his B.Sc. and M.Phil degrees. D:Ream had several hits on the UK charts, including “Things Can Only Get Better,” a No. 1 hit.

As of this writing he works as a particle physicist at the University of Manchester and at the Large Hadron Collider near Geneva, Switzerland. He married Gia Milinovich in 2003 and they have one child. He was elected in 2016 as a Fellow of the Royal Society, the UK’s national academy of sciences.

Cox is best known for his science outreach to the general public and has appeared on numerous BBC television and radio programs. Cox also lectures widely, has given several TED talks, and has co-authored several books about physics, including 2009’s Why Does E=mc²? (And Why Should We Care?).

Cox is a strong advocate for science education and government funding of scientific research. Asked by the Guardian (March 6, 2010) if he has “ever believed in God,” Cox replied, “No! I was sent to Sunday school for a few weeks but I didn’t like getting up on Sunday mornings. But some of my friends are religious. I don’t have a strong view on religion, other than illogical religion. Young earth creationism, for example: bollocks.”

Cox says the label of atheist does not apply to him because there is so much that is unknowable. His story “The Large Hadron Collider: A Scientific Creation Story” was one of 42 included in “The Atheist’s Guide to Christmas” in 2009. From the essay: “When the pattern of atoms known as you ceases to be, the building blocks will return to the voids of space and in a billion years or more they may take their place in another structure so beautiful that a future mind may perceive it to be the work of a god.”

PHOTO: The Royal Society

“So for me, the idea I would be able to have an entertaining and enjoyable afternoon discussing with people with whom I suppose I have to say I disagree at the most fundamental level, because I don’t have a particular faith, or any faith in fact – however, I think that difference of opinion and view of the world is to be celebrated and explored.”

— "Professor Brian Cox condemns 'toxic' rows between science and religion," Christian Today (Sept. 9, 2016)

Carolyn Porco

On this date in 1953, planetary scientist Carolyn C. Porco was born in Bronx, N.Y., where she was raised with four brothers, which she partly attributes to her career success in a field dominated by men. “I’m used to fighting and arguing with males,” she later quipped. Her father, an Italian immigrant, drove a bread truck, and her mother kept house while Carolyn attended Cardinal Spellman High School. (New York Times, Sept. 21, 2009)

Porco was a serious child, she recalled, “kind of like a 13-year-old going on 80.” She sought to find the meaning of her life. “The desire to know, to come to grips with my existence, brought me to seek the answer in the study of the cosmos. For a period of about four or five months, I tried to be a devout Catholic because that was the religion I was born into.” She went to Mass during the week and not just on Sunday “to get in God’s good graces. But it just felt like putting on a jacket that was too small.” (Violet magazine interview with Sasha Sagan, Nov. 23, 2020)

She earned an earth science B.S. from the State University of New York at Stony Brook in 1974 and a Ph.D. in geological and planetary sciences in 1983 from Caltech, where her dissertation was on discoveries in the rings of Saturn by the Voyager spacecraft. She joined the faculty of the Department of Planetary Sciences at the University of Arizona, where she would teach until 2001, and the Voyager Imaging Team.

Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 launched in 1977 on what became an interstellar journey among the four giant planets — Uranus, Saturn, Neptune and Jupiter — and 48 of their moons. Still operational as of this writing in 2022, they were respectively over 14 and 12 billion miles from Earth.

Porco co-originated the idea in 1990 to take a Voyager 1 “portrait of the planets,” including the famous “Pale Blue Dot” image of Earth, at the request of Voyager team member Carl Sagan, who coined the term. She was hired as a consultant for the movie “Contact” (1997), based on Sagan’s novel about a feisty astronomer played by Jodie Foster, and took strong exception to a plot wrinkle that the character should sleep with her adviser. (New York Times, Sept. 21, 2009)

She led the imaging team for the Cassini–Huygens mission launched in 1997 by NASA and the European and Italian space agencies and was the first to describe the behavior of the ringlets within Saturn’s rings. She led “The Day the Earth Smiled” effort that culminated with an image of Earth from 898 million miles away on July 19, 2013, and was a member of the imaging team for the New Horizons probe, which flew by Pluto in 2015.

Porco was a former student at Caltech of astrogeologist Eugene Shoemaker, who died in a car accident at age 69. He was also a Voyager Imaging Team member. As a tribute, she conceived a plan to “bury” a small amount of his cremains with a spacecraft that would impact the moon in 1999. She subsequently helped defend the plan from complaints by Navajo Nation president Albert Hale about defiling the “sacred” lunar landscape.

“The last time I looked there is a separation of church and state in this country,” Porco said. “Exploration of the moon is a secular activity and religious notions should not be imposed on it. Other religions have been able to accommodate scientific progress, and I hope that somehow the Navajos will be able to modify their beliefs, too.” About 1 ounce of ashes, encased in a polycarbonate tube, ended up buried in a crater where the Lunar Prospector probe’s mission was intentionally ended. (New York Times, Aug. 17, 1999)

(The above story link also helps explain Porco’s decision to remain single and focus solely on her work. She was 46 at the time. “Porco, who lives alone in the Tucson foothills, said she had little time for outside activities. ‘There are absolutely no high-maintenance items in my house of any kind — plants, pets or husbands.’ “)

She remains professionally active as a researcher, media contributor and public speaker, in addition to editing the Cassini Imaging Team’s website and as president of Diamond Sky Productions: “Our cause: Present science and its findings to the public.” Porco once said if you asked her if she believed in God, she would have two answers:

“In my capacity as a professional scientist, I would have to — I would be required to — be agnostic on the subject since I couldn’t say with scientific certainty that there is a God and I couldn’t with scientific certainty say that there isn’t.” But as a nonscientist, she added, “… then I’m going to have to say that my very strong faith, my very, very strong belief is that there is no God.” (“Enlightenment Living” by Ryan Somma, 2012)

In 2006, while working as a researcher at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo., she spoke at a forum at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego. She suggested, perhaps half in jest, establishing an alternative church headed by Neil deGrasse Tyson. “Let’s teach our children from a very young age about the story of the universe and its incredible richness and beauty,” Porco said. “It is already so much more glorious and awesome — and even comforting — than anything offered by any scripture or God concept I know.” (New York Times, Nov. 21, 2006)

Porco spoke at the Reason Rally in Washington in 2016. In response to a tweet saying “The pope is ashamed. Has he burned anyone at the stake yet?” (Aug. 19, 2018), she wrote: “The righteousness of the religious. I am ashamed to be of the same species.” She later deleted her tweet.

“The social organizations of religion provide … a means for people to feel connected to other people. But I think that science certainly can replace the God concept. As the saying goes, there isn’t much left for God to do because science has explained so much of it.”

— Porco interview, "Equal Time for Freethought," WBAI-NY Radio (Nov. 4, 2007)

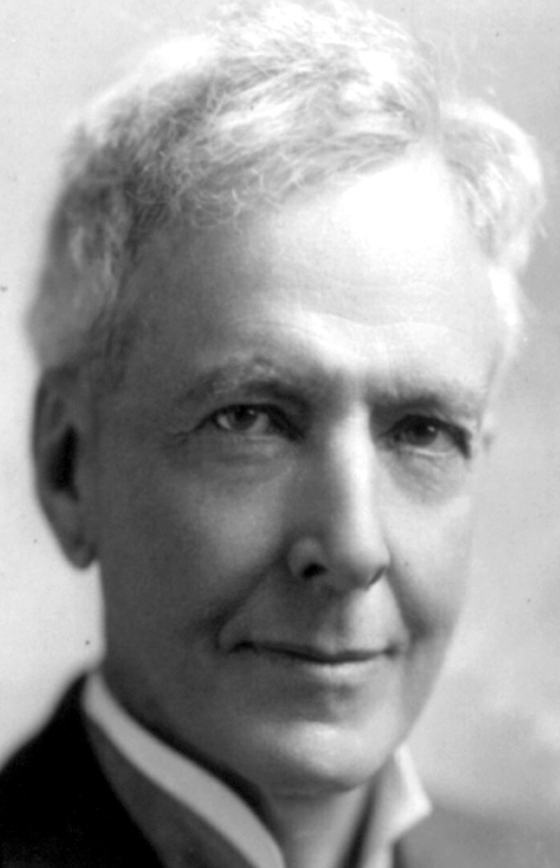

Luther Burbank

On this date in 1849, Luther Burbank was born in Lancaster, Mass. He found fame early when he single-handedly saved U.S. potato crops from the deadly blight by cultivating russet potatoes. The Burbank Russett is the most widely cultivated potato in the U.S. While running Burbank’s Experimental Farms in Santa Rosa, Calif., he produced more than 800 new varieties of fruits and plants.

Shaken by the Scopes “monkey” trial, Burbank wrote, “And to think of this great country in danger of being dominated by people ignorant enough to take a few ancient Babylonian legends as the canons of modern culture. Our scientific men are paying for their failure to speak out earlier. There is no use now talking evolution to these people. Their ears are stuffed with Genesis.”

In 1926, an interview about his freethought views appeared in the San Francisco Bulletin in which he declared “I am an infidel today,” adding,” I am a doubter, a questioner, a skeptic. When it can be proved to me that there is immortality, that there is resurrection beyond the gates of death, then will I believe. Until then, no.” He was inundated with mostly critical letters, which he felt he had to reply to personally. Friend and biographer Wilbur Hale attributed Burbank’s death at age 77 after suffering a heart attack to the exertion of his replies: “He died, not a martyr to truth, but a victim of the fatuity of blasting dogged falsehood.”

A crowd estimated at 10,000 came to his memorial and heard the openly atheistic tribute by Judge Lindsay of Denver. California still celebrates Burbank’s birthday as Arbor Day, planting trees in his memory. He married twice: to Helen Coleman in 1890, which ended in divorce in 1896, and to Elizabeth Waters in 1916. He had no children. (D. 1926)

“The idea that a good God would send people to a burning hell is utterly damnable to me. I don’t want to have anything to do with such a God.”

“I am an infidel today.”— Burbank interview in the San Francisco Bulletin (Jan. 22, 1926)

Alan Hale

On this date in 1958, Alan Hale, the co-discoverer in 1995 of Comet Hale-Bopp, was born in Tachikawa, Japan, where his father was in the U.S. Air Force. He grew up in Alamogordo, N.M., and graduated with a B.S. in physics in 1980 from the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md. He left the Navy in 1983 and began working at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., as an engineering contractor for the Deep Space Network.

While at the JPL he worked on spacecraft projects, including the Voyager 2 encounter with the planet Uranus in 1986. He then returned to New Mexico and earned advanced astronomy degrees, including a doctorate, at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces. In 1993 he founded the Southwest Institute for Space Research (now called the Earthrise Institute, where he is president).

Besides his research activities, Hale is an outspoken advocate for improved scientific literacy in our society and for better career opportunities for current and future scientists. He’s written for such publications as Astronomy, the International Comet Quarterly, the Skeptical Inquirer, Free Inquiry and the McGraw-Hill Yearbook of Science and Technology. He’s the author of Everybody’s Comet: A Layman’s Guide to Comet Hale-Bopp (High-Lonesome Books, 1996) and is a frequent public speaker on astronomy, space and other scientific issues.

Hale was a featured speaker at the FFRF’s 20th annual convention in Tampa, Fla., in 1997. The speech came in the aftermath that March of the suicides of 39 men and women who were part of the Heaven’s Gate UFO cult in Rancho Santa Fe, Calif. After claiming that a spaceship was trailing the Comet Hale-Bopp, cult leader Marshall Applewhite convinced his followers to kill themselves so their souls could board the spacecraft.

The members killed themselves in an orderly and disciplined fashion, over several days, in three teams, by taking a strong barbiturate with vodka, followed by a plastic bag over the head. All wore black clothes and brand-new Nike running shoes. All had packed a suitcase and had ID cards, a $5 bill and three quarters.

Hale called the death pact and other religion-fostered violence “another victory for ignorance and superstition.”

PHOTO: Courtesy of Alan Hale

“Oh, I have plenty of biases, all right. I’m quite biased toward depending upon what my senses and my intellect tell me about the world around me, and I’m quite biased against invoking mysterious mythical beings that other people want to claim exist but which they can offer no evidence for.”

“By telling students that the beliefs of a superstitious tribe thousands of years ago should be treated on an equal basis with the evidence collected with our most advanced equipment today is to completely undermine the entire process of scientific inquiry.”

“And one more thing: In your original message you identified yourself as an elementary school teacher. If you are going to insist on holding to a creationist viewpoint, then please stay away from my children. I want my kids to learn about ‘real’ science, and how the ‘real’ world operates, and not be fed the mythical goings-on in the fantasy-land of creationism.”

— Series of e-mails starting Jan. 14, 1997, retrieved from https://infidels.org/kiosk/article/email-conversation-with-a-creationist/

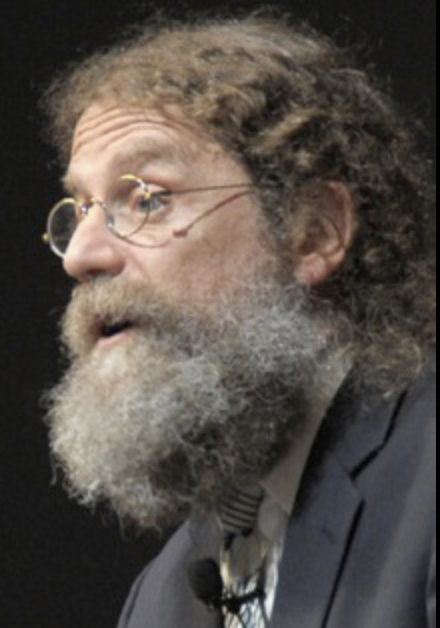

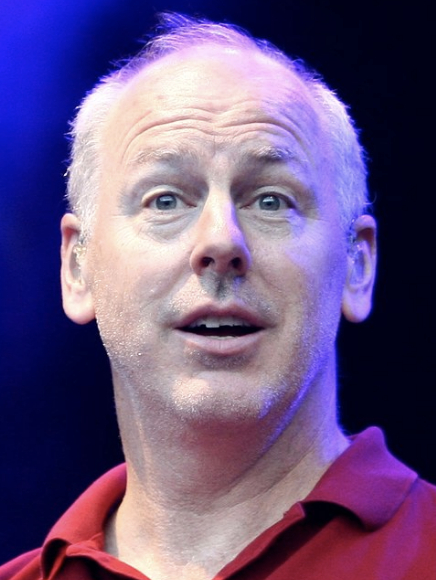

PZ Myers

On this day in 1957, biologist Paul Zachary “PZ” Myers was born. Myers is a biology professor at the University of Minnesota-Morris. His specialty is developmental biology and he is a proud proponent of science, evolution and atheism. He graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in zoology in 1979 and went on to earn his Ph.D in biology from the University of Oregon.

Before employment at UM-Morris, Myers worked at the University of Oregon, the University of Utah and Temple University. Myers studies zebrafish, spiders and cephalopods, an ink-squirting class of marine animals, most notably octopuses and squids.

“Pharyngula,” his very popular science blog, is partnered with National Geographic and has won numerous awards, including a 2005 Koufax Award for Best Expert Blog and an award from Nature. Myers was named Humanist of the Year in 2009 by the American Humanist Association, and won the International Humanist Award in 2011.

Myers makes his religious beliefs clear on Pharyngula: “If you’ve got a religious belief that withers in the face of observations of the natural world, you ought to rethink your beliefs — rethinking the world isn’t an option.” Commenting on his 2013 book The Happy Atheist, he said, “I’m an atheist swimming in a sea of superstition, surrounded by well-meaning, good people with whom I share a culture and similar concerns, and there’s only one thing I can do. I have to laugh.”

Myers at Ken Ham’s Creation Museum in Kentucky in 2009; syslfrog photo under CC 2.0.

“What I want to happen to religion in the future is this: I want it to be like bowling. It’s a hobby, something some people will enjoy, that has some virtues to it, that will have its own institutions and its traditions and its own television programming, and that families will enjoy together. It’s not something I want to ban or that should affect hiring and firing decisions, or that interferes with public policy. It will be perfectly harmless as long as we don’t elect our politicians on the basis of their bowling score, or go to war with people who play nine-pin instead of ten-pin, or use folklore about backspin to make decrees about how biology works.”

— Myers, interviewed in the 2008 documentary "Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed"

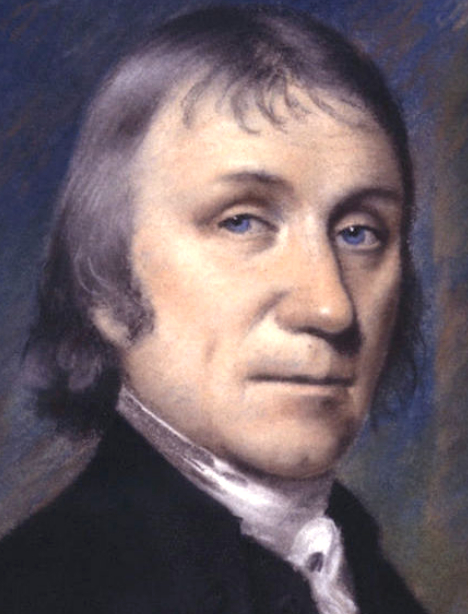

Joseph Priestley

On this date (under the Old Style calendar) in 1733, chemist and discoverer of oxygen Joseph Priestley was born in Fairhead, England, near Leeds, the oldest of six children. Destined for the ministry, Priestley realized he rejected much of Calvinism and decided to attend a Dissenting seminary, Daventry Academy. He worked as a minister while conducting scientific experiments and then secured a position at the Dissenting Academy, Warrington. He was eventually ordained and became an early founder of Unitarianism in England, at a time when Dissenters could be deprived of their citizenship and Unitarianism was not lawful.

He produced carbonated water and isolated eight gases in the air, including oxygen, and is considered to have laid the foundation for the science of chemistry. Priestley wrote The History and Present State of Electricity (1767) at the encouragement of his colleague Benjamin Franklin.

Priestley’s History of the Corruptions of Christianity (1782) was burned and reviled for its rejection of the Trinity, predestination and divine revelation. In it he averred that a pure form of Christianity had been corrupted. This was followed by History of Early Opinions Concerning Jesus Christ (1786). A General History of the Christian Church to the Fall of the Western Empire was finished in four volumes by 1803.

A defender of the French Revolution, Priestley lost his laboratory and home in Birmingham when they were stormed and burned down by mobs. His membership in the Royal Society was also withdrawn and he was burned in effigy. Priestley and his family emigrated to the U.S. in 1794 with hopes of setting up a model community but settled for building a house with a built-in lab in Northumberland, Pa., where he died at age 70 in 1804.

After weathering so much personal criticism, Priestley was notorious among freethinkers for writing about Franklin: “It is much to be lamented that a man of Dr. Franklin’s general good character and great influence should have been an unbeliever in Christianity and also have done so much as he did to make others unbelievers.” Priestley helped found the first Unitarian church in the U.S. (D. 1804)

What does Priestley mean, by an unbeliever, when he applies it to you? How much did he unbelieve himself? Gibbon had it right when he denominated his Creed, ‘scanty.’ “

— John Adams, in a letter to Thomas Jefferson (18 July 1813), "The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States, Vol.10" (1856)

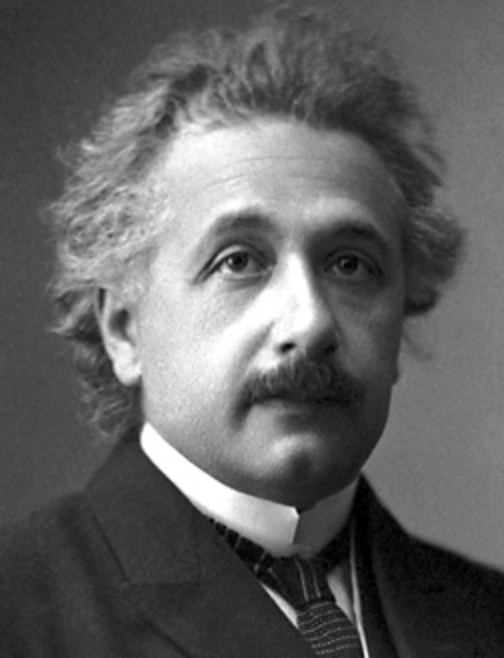

Albert Einstein

On this date in 1879, Albert Einstein was born in Ulm, Germany, to nonobservant Jewish parents. He attended a Catholic school from age 5 to 8. He completed his Ph.D. at the University of Zurich in 1909. His 1905 paper explaining the photo-electric effect — the basis of electronics — earned him the Nobel Prize in 1921. His first paper on Special Relativity Theory, also published in 1905, changed the world.

Einstein split his time and academic appointments between various European universities. After the rise of the Nazi Party, Einstein became a U.S. citizen in 1940 after moving to New Jersey in 1933 with his second wife and teaching at Princeton University.

A pacifist during World War I, he remained a firm proponent of social justice and responsibility. Einstein played a major role in the formation of what would become International Rescue Committee. He chaired the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, which organized to alert the public to the dangers of atomic warfare.

Einstein wrote often about his views on religion and wonder at the cosmic mysteries. Confusion over his beliefs stemmed from such comments as his public statement, reported by United Press on April 25, 1929, that: “I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the orderly harmony in being, not in a God who deals with the facts and actions of men.” Einstein’s famous “God does not play dice with the Universe” metaphor — meaning nature conforms to mathematical law — fueled more confusion.

At a symposium, he advised: “In their struggle for the ethical good, teachers of religion must have the stature to give up the doctrine of a personal God, that is, give up that source of fear and hope which in the past placed such vast power in the hands of priests. In their labors they will have to avail themselves of those forces which are capable of cultivating the Good, the True, and the Beautiful in humanity itself. This is, to be sure a more difficult but an incomparably more worthy task.” (“Science, Philosophy and Religion, A Symposium,” 1941)

In a letter to philosopher Eric Gutkind dated Jan. 3, 1954, Einstein continued to reject the idea of a personal god. Although saying he was proud to be a Jew, he said he was not impressed with Judaism. “The word god is for me nothing more than the expression and product of human weaknesses, the Bible a collection of venerable, but still primitive legends which are nevertheless pretty childish.” In 2018 the “God letter” sold for almost $2.9 million following a four-minute bidding battle at Christie’s.

He married Mileva Marić in 1903 and they had two sons. They had a daughter before marriage whose fate is unclear. She was either given up for adoption or died of scarlet fever. Their son Eduard was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age 20 and spent most of the rest of his life in asylums. After divorcing in 1919, Einstein married Elsa Löwenthal that same year after having a relationship with her since 1912. She was a first cousin maternally and a second cousin paternally. She was diagnosed with heart and kidney problems and died in December 1936.

He died of an abdominal aortic aneurysm at age 76 in Princeton. Pathologist Thomas Stolz Harvey removed his brain without the family’s permission and preserved it in formalin before Einstein was cremated. Harvey later cut the brain into 240 blocks, took tissue samples from each block, mounted them on microscope slides and distributed the slides to some of the world’s top neuropathologists for study. (D. 1955)

“Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hopes of reward after death. It is therefore easy to see why the churches have always fought science and persecuted its devotees.”

— Einstein column headlined "Religion and Science" (New York Times Magazine, Nov. 9, 1930)

William Smith

On this date in 1769, William Smith, known as the “Father of English Geology,” was born in Oxfordshire. Smith, who trained as an apprentice surveyor, single-handedly produced the world’s first geological map in 1815 of England, Wales and part of Scotland, spending 15 years on the project.

Smith, “whose agnosticism was well known,” according to biographer Simon Winchester, produced a “map that heralded the beginnings of a whole new science … a map that laid the foundations of a field of study that culminated in the work of Charles Darwin.”

In “The Map That Changed the World: William Smith and the Birth of Modern Geology” (2001), Winchester wrote: “It is a map whose making signified the start of an era, not yet over, that has been marked ever since by the excitement and astonishment of scientific discoveries that allowed man at last to stagger out from the fogs of religious dogma, and to come to understand something certain about his own origins and those of the planet.”

He also noted that “For the first time the earth had a provable history, a written record that paid no heed or obeisance to religious teaching and dogma, that declared its independence from the kind of faith that is no more than the blind acceptance of absurdity.”

Smith went bankrupt in 1819, spending several weeks in a debtors’ prison, then worked as an itinerant surveyor for many years. The Geological Society of London recognized his achievements by awarding him in 1831 its inaugural Wollaston Medal, the society’s highest honor. It’s named after William Hyde Wollaston, who discovered the elements palladium and rhodium and developed a process to turn platinum ore into malleable ingots.

Smith’s fossil collection is housed in the Natural History Museum, formerly part of the British Museum, in London. He died at age 70 in Northampton. (D. 1839)

“In 1793 William Smith, a canal digger, made a startling discovery that was to turn the fledgling science of the history of the Earth — and a central plank of established Christian religion — on its head.”

— Publisher's blurb, "The Map that Changed the World" (Harper, 2001)

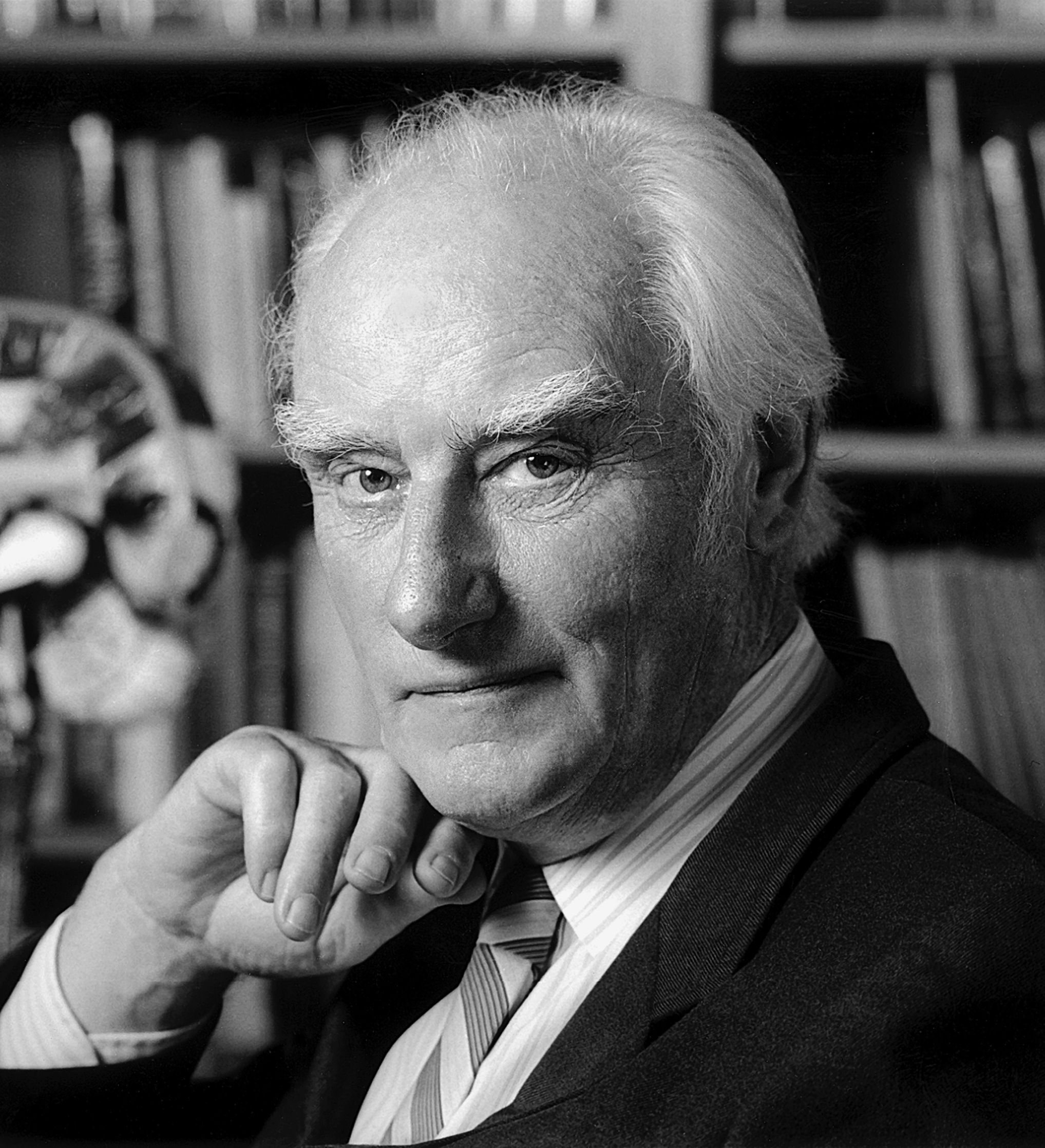

Richard Dawkins

On this date in 1941, evolutionary biologist and freethought champion Clinton Richard Dawkins was born in Nairobi, Kenya. His father, Clinton John Dawkins, was an agricultural civil servant in the British Colonial Service and served with the King’s African Rifles in World War II. The family returned to England in 1949. Dawkins graduated from the University of Oxford in 1962, then earned a philosophy doctorate and became an assistant professor of zoology at the University of California-Berkeley in 1967-69 and a Fellow of New College-Oxford in 1970.

Dawkins served as Charles Simonyi Chair of Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University from 1995-2008. In 2011 he joined the professoriate of the New College of the Humanities, founded by A.C. Grayling in London. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1997 and a Fellow of the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge in 2001.

The Selfish Gene, his first book, published in 1976, became an international best-seller. It was followed by The Extended Phenotype (1982), The Blind Watchmaker (1986), River Out of Eden (1995), Climbing Mount Improbable (1996), Unweaving the Rainbow (1998), A Devil’s Chaplain (2003) and The Ancestor’s Tale (2004). His iconoclastic book, The God Delusion, which he wrote with the public hope of turning believing readers into atheists, was published in 2006 to much acclaim.

He also produced several television documentaries decrying religion’s influence, including “Root of All Evil?” (2006) and “The Enemies of Reason” (2007). “The Genius of Charles Darwin” followed in 2008 and “The Meaning of Life” (2012) explored the implications of living without religious faith. In his memoir An Appetite for Wonder: The Making of a Scientist (2013), Dawkins chronicled his life up to publication of The Selfish Gene. A second memoir, Brief Candle in the Dark: My Life in Science, was published in 2015.

He founded the nonprofit Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science in 2006. It merged with the Center for Inquiry in 2016. The foundation finances research on the psychology of belief and religion, funds scientific education programs and supports secular charitable groups. Dawkins has advanced the concept of cultural inheritance or “memes,” also described as “viruses of the mind,” a category into which he places religious belief. He has also advanced the “replicator concept” of evolution.

A passionate atheist, Dawkins coined the memorable term “faith-heads” to describe certain religionists. His remarks in The Guardian (Feb, 6, 1999), “I’m like a pit bull terrier being released into the ring, as a spectator sport, to attack religious people” led to the nickname “Darwin’s pit bull.” His column for The Observer (Dec. 30, 2001) pointed out, “We deliberately set up, and massively subsidise, segregated faith schools. As if it were not enough that we fasten belief labels on babies at birth, those badges of mental apartheid are now reinforced and refreshed. In their separate schools, children are separately taught mutually incompatible beliefs.”

Dawkins was named the British Humanist Association’s 1999 Humanist of the Year in 1999 and received the International Cosmos Prize two years before that. In 2001 he was the recipient of an Emperor Has No Clothes Award from the Freedom From Religion Foundation but was unable to accept it in person because flights were grounded after 9/11. His written remarks accepting it are here. He accepted it in person in 2012 at the national convention in Portland, Ore.

He has been married three times and has a daughter, Juliet, born in 1984. Dawkins and Lalla Ward, who illustrated several of his books and other works, announced an “entirely amicable” separation in 2016 after 24 years of marriage. That same year he suffered a minor hemorrhagic stroke but reported later in the year that he had almost completely recovered.

PHOTO: By David Shinbone under CC 3.0.

“My respect for the Abrahamic religions went up in the smoke and choking dust of September 11th. The last vestige of respect for the taboo disappeared as I watched the ‘Day of Prayer’ in Washington Cathedral, where people of mutually incompatible faiths united in homage to the very force that caused the problem in the first place: religion. It is time for people of intellect, as opposed to people of faith, to stand up and say ‘Enough!’ ”

— "Time to Stand Up," written for the Freedom From Religion Foundation (September 2001)

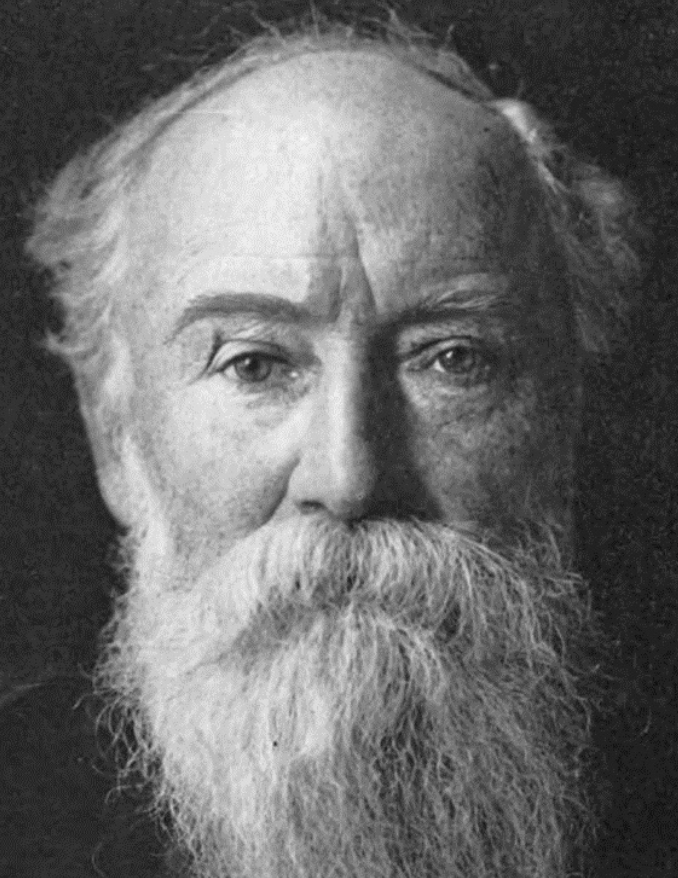

John Burroughs

On this date in 1837, naturalist John Burroughs was born on a farm in the Catskills of New York state. After teaching and clerking in government, Burroughs returned to the Catskills and devoted his life to writing and gardening. He knew Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, Theodore Roosevelt, John Muir and Walt Whitman, writing the first biography of Whitman. Most of his 22 books are collected essays on nature and philosophy.

In his book “The Light of Day“ (1900), he illuminated his views on religion: “If we take science as our sole guide, if we accept and hold fast that alone which is verifiable, the old theology must go.” “When I look up at the starry heavens at night and reflect upon what is it that I really see there, I am constrained to say, ‘There is no God.’ “

In his journal dated Feb. 18, 1910, he wrote: “Joy in the universe, and keen curiosity about it all — that has been my religion.” He died on his 83rd birthday. The John Burroughs Sanctuary can be found near West Park, N.Y., and his rustic cabin Slabsides has been preserved. (D. 1921)

“The deeper our insight into the methods of nature … the more incredible the popular Christianity seems to us.”

— Burroughs, "The Light of Day" (1900)

Robert M. Sapolsky

On this date in 1957, biologist and neuroendocrinologist Robert Morris Sapolsky was born in Brooklyn, New York. Sapolsky, whose parents emigrated from the Soviet Union, was raised in an Orthodox Jewish family in the Bensonhurst neighborhood. His father was an architect. He was a precocious student, teaching himself Swahili and writing letters to primatologists as a student at John Dewey High School on Coney Island.

He graduated from Harvard University in 1978 with a B.A. in biological anthropology and received his Ph.D. in neuroendocrinology from The Rockefeller University in New York City in 1984. He did post-doctoral work at the Salk Institute and was a research associate at the Institute of Primate Research, National Museums of Kenya. From 1978 until 1990 he spent three to four months a year living in a pup tent in Kenya to study the baboon population.

Sapolsky is a professor of biology, neurological sciences and neurosurgery at Stanford University. His work as a neuroendocrinologist has addressed the issues of stress and neuronal degeneration. Among the latest of his nearly 300 journal publications (as of this writing) is “This Is Your Brain on Nationalism: The Biology of Us and Them” (Foreign Affairs, 2019).

His books include Stress, the Aging Brain, and the Mechanisms of Neuron Death (1992), Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers (1994), Junk Food Monkeys (1997), The Trouble with Testosterone and Other Essays on the Biology of the Human Predicament (1998), the best-selling A Primate’s Memoir: A Neuroscientist’s Unconventional Life Among the Baboons (2001), Monkeyluv: And Other Essays on Our Lives as Animals (2005) and Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst (2017).

Sapolsky has received numerous honors and awards, including the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship Genius Grant in 1987 and the 2008 Carl Sagan Prize for Science Popularization. In 2002 he was the recipient of FFRF’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award (“Belief and Biology” acceptance speech). He is married to Lisa Sapolsky, a neuropsychologist. They have two children, Benjamin and Rachel.

PHOTO: Sapolsky in 2009; National Institutes of Health photo

“I was raised in an Orthodox household, and I was raised devoutly religious up until around age 13 or so. In my adolescent years, one of the defining actions in my life was breaking away from all religious belief whatsoever.”

— Robert Sapolsky, Emperor Has No Clothes Award acceptance speech (Nov. 23, 2003)

Clémence Royer

On this date in 1830, Clémence-Auguste Royer (née Augustine-Clémence Audouard) was born in Nantes, France. Her parents were Catholic royalists and didn’t marry until seven years after her birth. Her early education was in a convent school. Royer became a republican following the Revolution of 1848 and started to question other commonly held views. She obtained a teaching certificate and taught at girls schools in Wales, where she mastered English, and in France.

She read widely on science in these school libraries. In 1855, as a result of her inquiries, she rejected Catholicism thoroughly and devoted herself to science. She began to offer lectures on science and logic for women in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1858.

Royer translated Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species into French in 1863. She controversially added a 60-page preface which used Darwin’s mechanism for evolution as part of an anti-religious argument, which Darwin did not make. By this time the book was in its third English edition and contained several strong references to a creator. Royer had been an evolutionist before reading Darwin, having been strongly influenced by the writings of Jean Baptiste LaMarck.

French scientists, especially atheists and anthropologists, were strongly influenced by evolution and natural selection as framed by Royer, who also discussed the implications of evolutionary theory for human beings and society in her introduction. It would be almost 10 years before Darwin himself grappled with these issues in The Descent of Man. Royer continued as Darwin’s official French translator until the third French edition of Origin was published in 1870.

Royer, despite not being a research scientist, remained a popular interpreter of science as well as a philosopher of science. As a woman, she was denied access to many learned societies, as well as university teaching positions. It has been argued by Jennifer Michael Hecht and others that Royer opened doors to women within the freethinking movement. In 1866 she had a son, René, by her lover and life partner, Pascal Duprat, a married man, which sharpened her concern about the major legal obstacles then present to unwed mothers and their children.

She published many books and articles and considered the pinnacle to be Natura rerum, her theory of nature. In 1900 she was named a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor for her contributions as “a woman of letters and a scientific writer.” Royer died in 1902 at age 71. Her son died of liver failure six months later in Indochina. (D. 1902)

“Yes, I believe in revelation, but a permanent revelation of man to himself and by himself, a rational revelation that is nothing but the result of the progress of science and of the contemporary conscience, a revelation that is always only partial and relative and that is effectuated by the acquisition of new truths and even more by the elimination of ancient errors.”

— Royer, preface to Darwin's "L'origine des espèces," cited in Jennifer Michael Hecht's "The End of the Soul" (2003)

Richard Feynman

On this date in 1918, Richard Phillips Feynman was born in New York City. His parents were Lithuanian Jews. Feynman, with two other scientists, won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965 for his work in quantum electrodynamics. He received his undergrad degree from MIT in 1939 and his Ph.D. from Princeton in 1942. He worked at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico as part of the nuclear Manhattan Project, then became a professor at Cornell from 1945-50.

He became professor of theoretical physics at California Institute of Technology in 1950. When Physics World polled scientists asking them to rank the greatest physicists, Feynman was rated seventh, behind Galileo. He was a writer and personality as well. His first popular book was Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!: Adventures of a Curious Character (1985). His academic classic was the three-volume Lectures on Physics.

His sister Joan once said, “If you wanted to have a good party, you had Richard there.” (Los Angeles Times, Dec. 2, 2001.) In What Do You Care What Other People Think?: Further Adventures of a Curious Character (1988), Feynman said he gradually came to disbelieve the whole religion of Judaism as a teenager.

Feynman was first treated for stomach cancer in 1978. He made headlines after being appointed to a commission investigating the 1986 Challenger shuttle disaster, when he figured out and demonstrated what went wrong with the O-rings. (D. 1988)

PHOTO: Nobel Foundation

“One time, when I wasn’t there, somebody nominated me for president of the youth center. The elders began getting nervous, because I was an avowed atheist by that time.”

— "What Do You Care What Other People Think?: Further Adventures of a Curious Character" (1988)

Sally Ride

On this date in 1951, astronaut Sally Kristen Ride was born in Los Angeles, the firstborn child of Carol (née Anderson) and Dale Ride. She had one sibling, Karen, known as “Bear” throughout her life. Both parents were elders in the Presbyterian Church. Her mother worked as a volunteer counselor at a women’s correctional facility and taught Sunday school. Her father became a political science professor at Santa Monica College after his military service.

After high school, she enrolled at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania on a full scholarship. She played field hockey, golf and, most competitively, tennis. After three semesters she transferred to UCLA, where she was the only female physics major.

Dropping her goal of playing professional tennis, she transferred to Stanford University, graduating in 1973 with a B.S. in physics and a B.A. in English literature. She then earned an M.S. in physics and a doctorate in philosophy in 1978. Astrophysics and free-electron lasers were her areas of study. She wrote her doctoral dissertation on “the interaction of X-rays with the interstellar medium.”

Ride’s application to become an astronaut was one of 8,079 received, and in 1978 she was chosen by NASA with five other women to join the group of 35 new recruits. After serving as a ground-based mission specialist on two launches, at age 32 she became the first American woman to fly into space aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1983. Counting her second Challenger flight in 1984, she spent 343 hours in space.

Asked by Gloria Steinem in 1983 about “the dumbest kinds of questions you’ve been asked to date,” Ride said with a laugh: “Without a doubt, I think the worst question that I’ve gotten was whether I cried when we got malfunctions in the simulator. No.” (Steinem’s ABC-TV series “In Conversation With…”) She also said in the interview that “I wouldn’t even say that I’m spiritual. I honestly don’t think about religion at all.”

“Our parents taught us to explore, and we did,” her sister Bear would say later. “Sally studied science and I went to seminary. She became an astronaut and I was ordained as a Presbyterian minister. … Sally’s signature statement was ‘Reach for the Stars.’ Surely she did this, and she blazed a trail for all the rest of us.” (NBC News, July 24, 2012)

After dating astronaut Robert “Hoot” Gibson, in 1982 she married Steven Hawley, a member of her group of astronaut recruits. Bear Ride and Hawley’s minister father officiated. Ride and Hawley divorced in 1987.

Ride’s scheduled third flight was canceled when tragedy struck and the Space Shuttle Challenger blew up 73 seconds after launch on Jan. 28, 1986. All seven aboard died, including teacher-in-space Christa McAuliffe and astronaut Judith Resnik, who in 1984 was the second American woman in space.

Ride was appointed to the Rogers Commission investigating the disaster and was critical of NASA’s risk-assessment processes. She and Richard Feynman were instrumental in doggedly pursuing and helping reveal the cause of the explosion, the leaking O-ring seals on the booster rocket that let highly flammable gases escape.

After leaving NASA, she joined the physics faculty at the University of California-San Diego and led public outreach programs in cooperation with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. She served in 1999-2000 as president of Space.com, a company that aggregated news online about science and space. She then became president and CEO of Sally Ride Science, which she co-founded with Tam O’Shaughnessy to create programs and publications for upper elementary and middle school students, with a particular focus on girls.

After Ride was diagnosed in 2011 with pancreatic cancer, she and O’Shaughnessy registered their domestic partnership. She died at age 61 at home in 2012, with her cremains buried next to her father in a Santa Monica cemetery. Her obituary publicly revealed for the first time that O’Shaughnessy had been her partner for 27 years, which made Ride the first known LGBTQ+ astronaut.

Bear Ride confirmed the relationship, saying her sister chose to keep her personal life private, including her cancer and 17 months of debilitating treatments. “Sally lived her life to the fullest with boundless energy, curiosity, intelligence, passion, joy and love. Her integrity was absolute; her spirit was immeasurable; her approach to life was fearless. Sally died the same way she lived: without fear.” (Ibid., NBC News) (D. 2012)

PHOTO: Ride in 1984.

“Quite a few people have asked me since I’ve come back whether I’ve found religion in space or whether I had any mystical experiences while I was up there. No.”

— Ride interview with Gloria Steinem on "In Conversation With...” (ABC-TV, 1983)

Peter Higgs

On this date in 1929, Peter Ware Higgs was born in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. He graduated with honors in physics in 1950 from King’s College, University of London. He earned his master of science the next year and his Ph.D. in 1954, both from King’s. In his early 30s, Higgs began his career as lecturer in mathematical physics at the University of Edinburgh. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1974 and chair of theoretical physics in 1980. Higgs was elected Fellow of the Royal Society in 1983 and Fellow of the Institute of Physics in 1991.

In the 1960s he proposed the existence of a single particle responsible for imparting mass to all matter immediately following the Big Bang. (The Guardian, Nov. 16, 2007.) The Higgs boson, the scientific term for the particle, radically altered the field of physics, such that Higgs, according to Time magazine, ranks with physics giants like Albert Einstein, Isaac Newton and Democritus. Based on Higgs’ theory, scientists theorized a quantum field through which initially weightless particles move and acquire their mass. Higgs and François Englert were awarded the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physics for their work.

For several decades, a multi-billion dollar effort, including the construction of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at the CERN laboratory in Geneva, Switzerland, sought to find the Higgs boson particle. The LHC , the most powerful particle accelerator ever constructed, cost $6 billion and took 25 years to plan.

“Scientists … hope the [Large Hadron Collider] will produce clear signs of the boson, dubbed the ‘God particle’ by some, to the displeasure of Higgs, an atheist.” (Reuters, April 7, 2008) Despite his atheism, Higgs disliked the label for its potential to offend religious believers. He said Nobel Prize-winning physicist Leon Lederman was responsible for the term in a book Lederman co-authored: “He wanted to refer to it as that ‘goddamn particle’ and his editor wouldn’t let him.” (The Guardian, June 29, 2008)

Within two years of the original 2012 results at the LHC, the vast majority of particle physicists agreed that the Higgs particle discovery had been confirmed by multiple experiments and analyses. He died at age 94 at home in Edinburgh. (D. 2024)

PHOTO: Higgs at the 2013 Nobel Laureates press conference at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences; photo by Bengt Nyman under CC 2.0.

“I wish he hadn’t done it. I have to explain to people it was a joke. I’m an atheist.”

— Higgs, on Leon Lederman, the scientist who nicknamed the Higgs boson the "God particle." (The Guardian, Nov. 16, 2007)

A. Stone Freedberg

On this date in 1908, Abraham Stone Freedberg was born in Salem, Mass. Freedberg attended Harvard College and the University of Chicago Medical School (graduating in 1934). A professor at Harvard who taught medical students physical diagnosis techniques, Freedberg also became chairman of cardiology and internal medicine at the Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. As a professor and member of the admissions committee, he set out to help disadvantaged students navigate the admissions process at the medical school.

Until Freedberg invented a treatment in the late 1940s involving a radioactive iodine technique, patients with severe angina had no way to relieve their pain. In 1940 he was started studying ulcers, but his findings were not confirmed until 1983 by two Australian scientists, who would each win a Nobel Prize in 2005 for those findings. It has been confirmed by medical scientists that if Freedberg’s findings had been recognized earlier, treatments for ulcers would have been available decades sooner.

Freedberg later became a critic of doctors relying too heavily on technologically advanced testing methods, preferring the less expensive and, to him, more reliable practice of physical diagnosis. He stopped practicing medicine in his mid-90s.

Freedberg, who attended 100 classical music concerts in his 101st year, was an atheist. According to The New York Times, in Freedberg’s last days, he assessed his body and said there were no prospects “of a significant improvement in my basic status. … It is time to draw the curtain.” He died in his sleep at home in Boston at age 101. The Times obituary called him “an avowed atheist.” (D. 2009)

“He always said that he just wanted to go to sleep and not wake up. He said to us, ‘It’s time,’ and he went to sleep.”

— Freedberg's son Richard, quoted in "A. Stone Freedberg, 101, Harvard med school professor" (Boston Globe, Aug. 24, 2009)

James Hutton

On this date in 1726, James Hutton was born in Edinburgh, Scotland. He enrolled at Edinburgh University in 1740 to study law but switched to medicine, earning his M.D. in 1749 in Leiden, in what is now the Netherlands. Hutton never practiced medicine, instead devoting himself in turn to the manufacture of ammonium chloride, the study of new agricultural methods and the construction of canals. Hutton became interested in geology in the 1750s, journeying through England, Wales and Scotland to study rock formations.

One of Hutton’s major contributions to the field of geology was the discovery in 1785 that granite is an igneous, rather than sedimentary rock (formed from cooling magma, not from compacted sediments). Hutton is perhaps best known for the theory of Uniformitarianism, or the idea that the only processes that can have acted on the Earth’s surface are processes we see around us today — for example, erosion, deposition of sediments and volcanic activity.

The prevailing 18th-century theory was Catastrophism: the idea that many great catastrophes, such as floods, caused relatively rapid rock formation and landform change. In England especially, geologists were eager to reconcile their theories with the biblical accounts of Genesis; theories that posited catastrophic floods remained popular because they fit well with the biblical story of Noah. Theories such as Hutton’s, which required vastly more time than the bible allowed, were seen as especially suspect.

Hutton was a deist, who believed that the world had been created for humans’ eventual emergence; however, he did not believe that God interfered in the world, so that the miraculous-seeming events of Catastrophism seemed impossible to him. Hutton explained his geological theories in Theory of the Earth, the first two volumes of which were published in 1795. The third was published posthumously in 1899. He was a famously abstruse writer, whose works were not much read, but John Playfair, his biographer, published Illustrations of the Huttonian Theory of the Earth in 1802, which popularized Hutton’s difficult material.

Hutton never married, living with his sisters for much of his adult life. He did, however, father a child, also named James Hutton, during his student years. (D. 1797)

“The past history of our globe must be explained by what can be seen to be happening now. No powers are to be employed that are not natural to the globe, no action to be admitted except those of which we know the principle.”

— Hutton, "Theory of the Earth," Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1785)

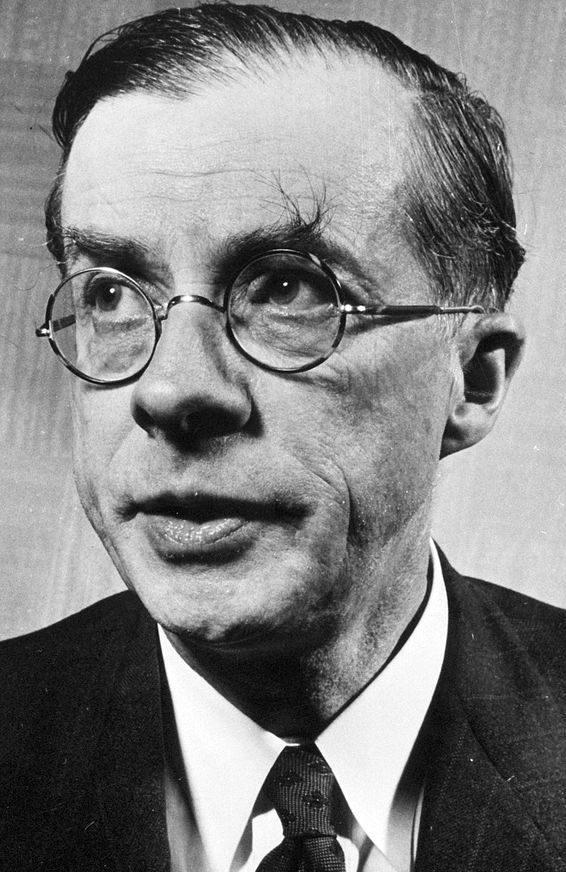

Francis Crick

On this date in 1916, Francis Crick was born in Northampton, England. He studied physics at University College, London, earned a B.Sc. in 1937, and began research for a Ph.D., which was interrupted by the outbreak of World War II. He served as a scientist for the British Admiralty, which he left in 1947 to study biology. He joined the Medical Research Council Unit in Cavendish Laboratory Cambridge, and obtained a Ph.D. in 1954.

He met James Watson in 1951 and together they proposed the double-helix structure for DNA by 1953. In 1962, he, Watson and Maurice Wilkins won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their long-awaited breakthrough in determining the structure and replication scheme of DNA. Rosalind Franklin, who died in 1958, is now often credited as a co-discoverer.

Crick taught at various universities, including Harvard, Cambridge and University College, London, and became a non-resident Fellow of Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego. In a book recapping his career, What a Mad Pursuit, Crick writes candidly of his rejection of religion. As a school boy, “I was a skeptic, an agnostic, with a strong inclination toward atheism.” D. 2004.

“I realized early on that it is detailed scientific knowledge which makes certain religious beliefs untenable. A knowledge of the true age of the earth and of the fossil record makes it impossible for any balanced intellect to believe in the literal truth of every part of the Bible in the way that fundamentalists do. And if some of the Bible is manifestly wrong, why should any of the rest of it be accepted automatically?”

— Crick, "What Mad Pursuit: A Personal View of Scientific Discovery" (1988)

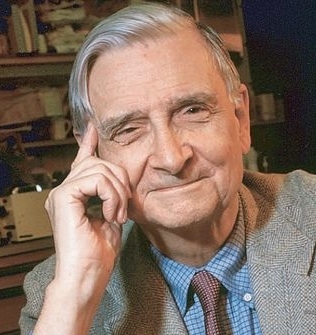

E.O. Wilson

On this date in 1929, biologist and author Edward Osborne Wilson was born in Birmingham, Ala. His father, Edward Osborne Wilson Sr., worked as an accountant. His mother, Inez Linnette Freeman, was a secretary. They divorced when he was 8. He had a nomadic childhood, mostly with his father, an alcoholic who would kill himself.

Wilson earned his B.S. and M.S. in biology from the University of Alabama and a Ph.D. in 1955 from Harvard, the same year he married Irene Kelley. They had a daughter, Catherine. He joined the Harvard faculty in 1956, where he retired in 2002 at age 73, although he published more than a dozen books after that.

Blinded in one eye by a fishing accident as a child, his research focus was in the field of myrmecology, the study of ants. He discovered the chemical means by which ants communicate. His books include The Insect Societies (1971) and The Ants (1990), co-written with Bert Holldobler, which won the 1991 Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction. Wilson’s On Human Nature won a Pulitzer in 1979.

Wilson is perhaps best known for his intellectual syntheses, often connecting evolution and biology to other disciplines. His 1967 book, The Theory of Island Biogeography, which develops the mathematics of how species evolve in geographically small habitats, is influential in the fields of ecology and practical conservation. He worked out the importance of habitat size and position within the landscape in sustaining animal populations.

In 1975 he published Sociobiology: A New Synthesis, which connected the evolution of social insects with other animals, including humans. At the time, the idea that human behavior is genetically influenced was very controversial and Wilson was criticized as racist and sympathetic to eugenics. During a 1978 lecture he had a pitcher of water poured on his head while the attacker exclaimed, “Wilson, you’re all wet.”

More recently, Wilson was criticized by Monica McLemore, an associate professor at UC-San Francisco, for espousing “theories fraught with racist ideas about distributions of health and illness in populations without any attention to the context in which these distributions occur.” She added that “what works for ants and other nonhuman species is not always relevant for health and/or human outcomes. For example, the associations of Black people with poor health outcomes, economic disadvantage and reduced life expectancy can be explained by structural racism, yet Blackness or Black culture is frequently cited as the driver of those health disparities. Ant culture is hierarchal and matriarchal, based on human understandings of gender. And the descriptions and importance of ant societies existing as colonies is a component of Wilson’s work that should have been critiqued. Context matters.” (Scienfic American, Dec. 29, 2021)

Wilson expanded on the ideas propounded in Sociobiology in On Human Nature (1978), which spawned the discipline of evolutionary psychology. While initially widely accepted with some enthusiasm, some aspects of evolutionary psychology research became even more controversial than Sociobiology, with the line between the two fields becoming more blurred.

Wilson’s parents were Southern Baptists though he was also raised by conservative Methodists. He abandoned Christianity before college, later describing himself as a “provisional deist” and agnostic. In On Human Nature, he argued that belief in God and rituals of religion are products of evolution. He disdained the tribalism of religion: “And every tribe, no matter how generous, benign, loving, and charitable, nonetheless looks down on all other tribes. What’s dragging us down is religious faith.”

In Esquire magazine (Jan. 5, 2009), Wilson said: “If someone could actually prove scientifically that there is such a thing as a supernatural force, it would be one of the greatest discoveries in the history of science. So the notion that somehow scientists are resisting it is ludicrous.”

He has been honored by the American Humanist Association twice, in 1982 with the Distinguished Humanist prize and again in 1999 as the Humanist of the Year. In 1990, he was awarded the Royal Swedish Academy of Science’s Crafoord Prize in ecology, considered the field’s highest honor. He died in Massachusetts at age 92. (D. 2021)

PHOTO by Jim Harrison under CC 2.5.

“So I would say that for the sake of human progress, the best thing we could possibly do would be to diminish, to the point of eliminating, religious faiths.”

— Interview, New Scientist (Jan. 21, 2015)

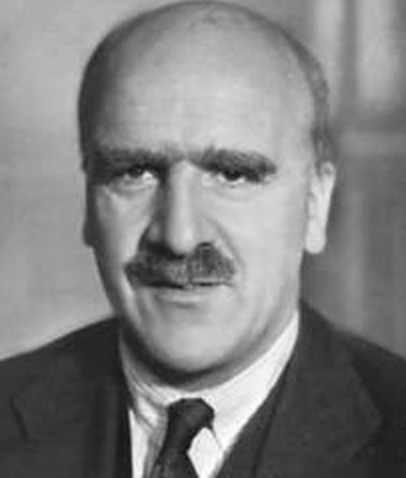

Julian Huxley

On this date in 1887, Julian Huxley, the brother of novelist Aldous Huxley and the grandson of agnostic biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, was born in Great Britain. Educated as a biologist at Oxford, he taught at Rice Institute, Houston (1912-16), Oxford (1919-25) and Kings College (1925-35). An ant specialist (he wrote a book called Ants in 1930), Huxley was secretary of the Zoological Society of London (1935-42) and UNESCO’s first general director (1946-48). A strong secular humanist, Huxley called himself “not merely agnostic. … I disbelieve in a personal God in any sense in which that phrase is ordinarily used.” (Religion Without Revelation, 1927, revised 1956)

Huxley was an early evolutionary theorist with versatile academic interests. Some of his many other books include Essays of a Biologist (1923), Animal Biology (with J.B.S. Haldane, 1927), The Science of Life (with H.G. Wells, 1931), Thomas Huxley’s Diary of the Voyage of the HMS Rattlesnake (editor, 1935), The Living Thoughts of Darwin (1939), Heredity, East & West (1949), Biological Aspects of Cancer (1957), Towards a New Humanism (1957) and Memories, a two-volume autobiography in the early 1970s. Huxley was knighted in 1958 and was also a founder of the World Wildlife Fund. (D. 1975)

PHOTO: Huxley in 1964. Dutch National Archives, The Hague, Creative Commons.

“Operationally, God is beginning to resemble not a ruler, but the last fading smile of a cosmic Cheshire Cat.”

— Julian Huxley, "Religion Without Revelation" (1927)

J.B.S. Haldane (Quote)

“I’ve never met a healthy person who worried much about his health, or a good person who worried much about his soul.”

— J.B.S. Haldane, British scientist (1892-1964). "Dictionary of Humorous Quotations," edited by Evan Esar (1949)

Harriet Hall