attorneys-judges

François-Désiré Bancel

On this date in 1822, François-Désiré Bancel was born in France. He was educated at Touron and Grenoble, became a lawyer and then a member of the Legislative Assembly in 1849. Bancel was known as one of the most passionate critics of the royalists and clerics. After Napoleon III expelled him in 1852, he moved to Brussels and taught at the Free University.

A deist, according to freethought historian Joseph McCabe, he “gave great assistance in the Belgian Rationalist movement.” Bancel was again elected to the legislature in 1869 upon his return to France. A boulevard in Valence and a street in Lyon bear his name. (D. 1871)

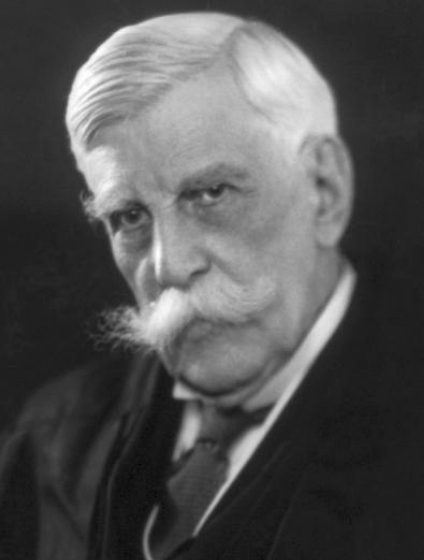

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

On this date in 1841, jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., was born in Boston. He was the namesake and son of a famed physician. Holmes graduated from Harvard in 1861 and immediately enlisted in the U.S. Army, where he was seriously wounded three times. After the Civil War he entered Harvard Law School, where his best friend was William James.

Holmes’ New York Times obituary noted that the two young men went to Europe together, “while James went on, continuing in Germany his search for the meanings of the universe, Holmes decided that ‘maybe the universe is too great a swell to have a meaning,’ that his task was to ‘make his own universe livable,’ and he dove deep into the study of the law.”

Holmes was admitted to the bar in 1866. He became coeditor of the American Law Review in 1870. Holmes wrote his legal treatise, The Common Law, in 1881, a 15-year labor. His recodification of the law from religious foundations to modern jurisprudence was pivotal to the evolution of legal scholarship. Holmes urged “judicial restraint,” or the divorcing of private views from legal opinions.

While he was a professor at Harvard Law School, he was appointed at age 41 as an associate justice on the Massachusetts Supreme Court, eventually becoming chief justice. Theodore Roosevelt appointed him to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1902. He retired in 1932 as the oldest judge (age 91) to serve. Holmes earned the sobriquet “The Great Dissenter” for his many famous dissents, some of which have long since been adopted as mainstream by courts.

Among his well-known legal adages: “The mind of the bigot is like the pupil of the eye: the more light you shine on it, the more it will contract.” “Taxes are the price we pay for a civilized society.” “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.” “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theater.” “The right to swing my fist ends where the other man’s nose begins.” Holmes, like his father, was a Unitarian, who believed in a god but was creedless.

He was married to Fanny Bowditch Dixwell from 1872 until her death in 1929. They never had children but raised an orphaned cousin. He died of pneumonia in 1935, two days short of his 94th birthday. He left his estate to the U.S. government.

"When men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas — that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes can be carried out. That, at any rate, is the theory of our Constitution."

— Holmes, quoted in his New York Times obituary (March 1935)

J.B. Stallo

On this date in 1823, Johann Bernard Stallo, academic, religious dissenter, jurist, political philosopher and ambassador, was born in the Catholic village of Damme in Germany. He studied at home, as well as at a Catholic school. Since his family could not afford to send him to a gymnasium (a secondary school with an emphasis on preparing students for higher education), Stallo emigrated to the United States in 1839. He settled in Cincinnati, close to extended family, and met his wife Helena Zimmerman in 1850. The couple had 10 children, five of which survived childhood.

Stallo taught at numerous Jesuit institutions until he was admitted to the bar and began practicing law in 1849. Contradicting his involvement in religious schools, he played a critical role in the Cincinnati Bible War, a longstanding local “war” between Protestants, Catholics and Jews over the role of religion in their public schools (specifically whether or not the King James version of the bible should be used as reading material in classrooms). The decision by the board of education against using the bible paved the way for secularization in numerous other school districts.

Stallo also participated in the Liberal Republican movement of 1872, organized to oppose the reelection of President Ulysses S. Grant and his supporters. Before he retired to Florence, Italy, Stallo’s most famous works were published, such as The Concepts and Theories of Modern Physics (1882), which represents some of the early thought that led to the modern philosophy of science. (D. 1900)

PHOTO: Portrait of Stallo from the frontispiece of “The Concepts and Theories of Modern Physics.”

"Government can protect and help to maintain religion, as well as everything else which constitutes the life of the soul, only in one way — by guarding the freedom of its development. Whoever asks it to do more is seeking to convert it into an abominable engine of tyranny and oppression."

— Stallo, "State creeds and their modern apostles," lecture delivered in the First Congregational Unitarian Church, Cincinnati (April 3, 1870)

Marilla Ricker

On this date in 1840, Marilla Marks Ricker (née Young) was born in New Durham, New Hampshire. She became a trail-blazing attorney, abolitionist, humanitarian and suffragist. Her father, Jonathan Young, reportedly related to Mormon prophet Brigham Young, was a freethinker and proponent of women’s rights who took her to courtrooms and town meetings.

As a child she witnessed a “fiery” sermon about hell at her mother’s Free Will Baptist church, she later wrote. (Boston Business Folio, 1895.) “Do you wonder that I, a child of ten years, said to my father, who was a freethinker, infidel, atheist, or whatever else you please to call him: ‘I hate my mother’s church. I will not go there again.’ “

She started teaching at age 16, refusing to read from the bible during class, instead preferring literary works, including those of Emerson. When the school committee told her bible reading was mandatory, she refused to comply and left the profession.

In 1863 she married John Ricker, a man 33 years her senior. He died five years later, leaving an estate that made her financially independent. She studied law in Washington, D.C., determined to help the downtrodden. She passed the bar with the highest grade of anyone admitted in 1882. Her first public courtroom appearance was as assistant counsel to Robert G. Ingersoll and became known as the “prisoner’s friend,” successfully challenging a district law that indefinitely confined poor criminals unable to pay fees.

Ricker in 1871 had the distinction of being the first U.S. woman to vote using the argument that women were “electors” under the Fourteenth Amendment. In 1890 she won the right of women to practice law in New Hampshire. She was admitted to the U.S. Supreme Court bar in 1891. She was denied the right to run for governor of New Hampshire in 1910 on a woman’s rights platform by the state attorney general. Her books include The Four Gospels (1911), I Don’t Know, Do You? (1916) and I Am Not Afraid, Are You? (1917).

In I Am Not Afraid she wrote: “A religious person is a dangerous person. He may not become a thief or a murderer, but he is liable to become a nuisance. He carries with him many foolish and harmful superstitions, and he is possessed with the notion that it is his duty to give these superstitions to others.” (D. 1920)

“A steeple is no more to be excluded from taxation than a smoke stack.”

— Ricker, "I Am Not Afraid, Are You?" (1917)

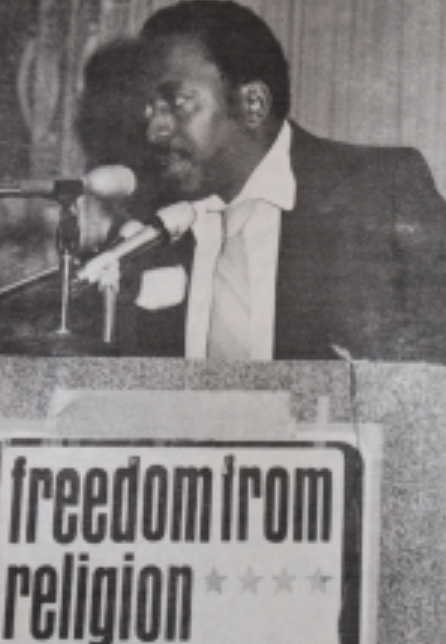

Ishmael Jaffree

On this date in 1944, Ishmael Jaffree (né Frederick Hobbs) was born two months prematurely in a Cleveland home for unwed mothers. His mother was very religious and he never knew his father. Jaffree brought and won the U.S. Supreme Court decision Wallace v. Jaffree, 472 U.S. 38, 72 (1985). Calling him “an authentic American hero,” FFRF inaugurated its Freethinker of the Year award at its 1985 convention to recognize his contributions.

As a child he evangelized on Cleveland street corners, “exhorting sinners to get right with God,” according to a People magazine story (June 24, 1985). At Cleveland State University, he was influenced by a black atheist professor named Jaffree. “I started considering myself an Existentialist. I no longer believed the Christian faith was the faith and that Jesus Christ had blue eyes and white skin.” He changed his name in 1972 to reject “the slave-master path. Ishmael means outcast.”

He married Mozelle Hurst in 1974 after finishing law school. They moved to Alabama in 1977, where he set up a law practice in Mobile. He discovered in 1981 that his children were being fed daily doses of the Lord’s Prayer and grace at lunch, with an occasional bible reading. Jaffree bravely filed a lawsuit in May 1982, challenging a 1978 law authorizing a one-minute period of silence, a 1981 statute authorizing a period of silence “for meditation or voluntary prayer,” and a 1982 law authorizing teachers to lead “willing students” in a prescribed prayer to “Almighty God … the Creator and Supreme Judge of the world.”

During the 1982 trial, U.S. District Judge William Brevard Hand allowed 600 Christians to intervene; school officials led children in prayer in front of media. Jaffree’s children were ostracized, laughed at and subjected to racial epithets and physical harassment. Hand ruled against Jaffree in 1983, claiming the Supreme Court was wrong about state-church separation and that the First Amendment does not bar states from establishing a religion. The case proceeded by way of the 11th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court.

On June 4, 1985, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in Jaffree’s favor, declaring unconstitutional a period of silence for “meditation or voluntary prayer” in public schools.

{Hand received more national attention two years later when he ruled for plaintiffs who claimed Alabama textbooks promoted secular humanism and violated the Establishment Clause. Hand, appointed as a federal judge by President Nixon, ordered statewide removal of textbooks in home economics, history and social studies. The 11th Circuit later overruled him unanimously.)

"I brought the case because I wanted to encourage toleration among my children. I certainly did not want teachers who have control over my children for at least eight hours over the day to … program them into any religious philosophy."

— Jaffree, acceptance speech as FFRF's first Freethinker of the Year (1985)

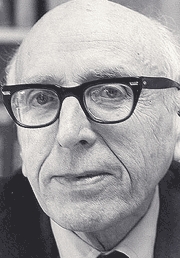

Clarence Darrow

On this date in 1857, Clarence Darrow, later dubbed “Attorney for the Damned” and “the Great Defender,” was born in Farmdale, Ohio. For a time he lived in a home that had served as a stop on the Underground Railroad. His father was known as the “village infidel.” Darrow attended the University of Michigan Law School for one year, then passed the bar in 1878 and moved to Chicago. There he joined protests against the trumped-up charges against four radicals accused in the Haymarket Riot case.

Darrow became corporate counsel for the city of Chicago, then counsel for the Chicago & North Western Railway. He quit this lucrative post when he could no longer defend their treatment of injured workers, then went on to defend without pay socialist striker Eugene V. Debs. In 1907, Darrow successfully defended labor activist “Big Bill” Haywood, charged with assassinating a former governor. His passionate denunciation of the death penalty prompted him to defend the famous killers, Loeb and Leopold, who received life sentences in 1924.

His most celebrated case was the Scopes Trial, defending teacher John Scopes in Dayton, Tenn., who was charged with the crime of teaching evolution in the public schools. Darrow’s brilliant cross-examination of prosecuting attorney William Jennings Bryan lives on in legal history. During the trial, Darrow said: “I do not consider it an insult, but rather a compliment to be called an agnostic. I do not pretend to know where many ignorant men are sure — that is all that agnosticism means.”

Darrow wrote many freethought articles and edited a freethought collection. His two appealing autobiographies are The Story of My Life (1932), containing his plainspoken views on religion, and Farmington (1932). He also wrote Resist Not Evil (1902), An Eye for An Eye (1905), and Crime, Its Causes and Treatments (1925). His freethought writings are collected into Why I Am an Agnostic and Other Essays. He told The New York Times, “Religion is the belief in future life and in God. I don’t believe in either.” (April 19, 1936)

He married Jessie Ohl in 1880 and they had a son, Paul Edward, in 1883 before divorcing in 1897. Darrow married Ruby Hammerstrom, a journalist 16 years his junior, in 1903. He died at age 80 of heart disease. (D. 1938)

PHOTO: Darrow in 1922.

"I don’t believe in God because I don’t believe in Mother Goose."

— Darrow, 1930 speech, Toronto, Canada

Erwin Chemerinsky

On this date in 1953, legal scholar Erwin Chemerinsky was born to Arthur and Raeda Chemerinsky, a working-class Jewish couple from Chicago’s South Side. He earned a bachelor’s degree in communication from Northwestern University in 1975 and graduated cum laude from Harvard Law School in 1978 while working with the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau.

He taught law at DePaul University, the University of Southern California and at Duke University before becoming the founding dean of the University of California-Irvine School of Law and Raymond Pryke Professor of First Amendment Law in 2008. He married Catherine L. Fisk in 1993. She is a law professor at UC-Irvine who has degrees from the University of Wisconsin and UC-Berkeley.

Chemerinsky was elected in April 2016 to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His areas of expertise are constitutional law, federal practice, civil rights and civil liberties and appellate litigation. He’s the author of eight books, including The Case Against the Supreme Court (2014) and The Conservative Assault on the Constitution (2010) and has had over 200 articles published in top law reviews and journals.

In January 2014, National Jurist magazine named him the most influential U.S. legal educator. (He finished second to Cass Sunstein in 2015.) In 2014, FFRF named him a Champion of the First Amendment, an award he accepted at FFRF’s national convention in Los Angeles. His convention speech was titled “The Vanishing Wall Separating Church and State.”

PHOTO: Ingrid Laas

“The thesis of my remarks is a simple one: Now more than ever, we need the Freedom From Religion Foundation. In 1947 in Everson v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court held that the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment applies to state and local governments. All nine justices believed that the Establishment Clause was meant to create a wall that separates church and state. Now for the first time since 1947, a majority of the court rejects that notion. We have a Supreme Court that is hostile toward freedom from religion.”

— FFRF convention speech, Oct. 25, 2014

Michael Newdow

On this date in 1953, Michael Arthur Newdow, an attorney and emergency room physician, was born to nominally Jewish parents. He grew up in the Bronx, N.Y., and Teaneck, N.J., and earned a B.S. in biology from Brown University. In 2004 he told Brown’s alumni magazine that “I was born an atheist.” He graduated from UCLA’s medical school in 1978 and earned a law degree from the University of Michigan in 1988. In 1977, he was ordained as a minister in the Universal Life Church, based in Modesto, Calif., a “church” which has but one basic tenet: “Do only that which is right.”

In 1997 he formed an organization called FACTS (First Atheist Church of True Science), which advocates for a strong wall between state and church. Newdow has filed several lawsuits challenging the mingling of religion and government. One, Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow, was argued before the U.S. Supreme Court in 2004. The issues at hand: Whether a public school district policy that required teachers to lead students in reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, which included the words “under God,” was a violation of the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, and whether Newdow had legal standing on behalf of his daughter to challenge the policy.

The 9th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals ruled in his favor in 2002 that “under God” in school pledges was unconstitutional. Circuit Judge Alfred T. Goodwin, a 79-year-old Nixon appointee, famously wrote: “A profession that we are a nation ‘under God’ is identical to a profession that we are a nation ‘under Jesus,’ a nation ‘under Vishnu,’ a nation ‘under Zeus,’ or a nation ‘under no god.’ ”

The appeals court ruling was appealed to the Supreme Court, which ruled 5-3 that Newdow didn’t have standing in the case because he didn’t have sufficient custody over his daughter, whose mother had primary custody. “No one who managed to get a seat in the courtroom is likely ever to forget his spellbinding performance,” New York Times court reporter Linda Greenhouse said of Newdow’s oral argument.

What he saw as unconstitutional endorsement of religion led Newdow to file other suits, including one to remove “In God We Trust” from U.S. coins and currency and others to block religious invocations at presidential inaugurations, use of “so help me God” when administering the oath of office and use of official chaplains in Congress. FFRF named Newdow its Freethinker of the Year in 2002 and a Freethought Hero in 2004.

“Mr. Chief Justice, and may it please the Court:

Every school morning in the Elk Grove Unified School District’s public schools, government agents, teachers, funded with tax dollars, have their students stand up, including my daughter, face the flag of the United States of America, place their hands over their hearts, and affirm that ours is a nation under some particular religious entity, the appreciation of which is not accepted by numerous people, such as myself. We cannot in good conscience accept the idea that there exists a deity.

I am an atheist. I don’t believe in God. And every school morning my child is asked to stand up, face that flag, put her hand over her heart, and say that her father is wrong.”

— Newdow's oral argument to the U.S. Supreme Court, March 24, 2004 (The Oyez Project)

Harriet Johnson

On this date in 1957, Harriet McBryde Johnson was born in eastern North Carolina. Johnson was a civil rights lawyer in Charleston and a disability rights advocate. She advocated for the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, and spoke powerfully about her own experience with her disability. Johnson was born with a degenerative neuromuscular condition — she was unconcerned with the specific diagnosis — and used a motorized wheelchair as an adult. She represented disabled people in court, ran for local office and was active in the disability-rights group Not Dead Yet, which advocates against physician-assisted suicide and opposes the idea of euthanasia of severely disabled infants.

Johnson was involved in a private correspondence with philosopher Peter Singer, also an atheist. The two debated the idea of euthanasia of severely disabled infants at Princeton University in 2003. Johnson published many opinion pieces and personal narratives in national newspapers, such as The New York Times, and wrote two books, Too Late to Die Young (2005) and Accidents of Nature (2006). She also spoke out against the “charity mentality” surrounding disability, and was publicly opposed to the “Jerry Lewis Muscular Dystrophy Telethon.” (D. 2008)

"As an atheist, I think all preferences are moot once you kill someone. The injury is entirely to the surviving community."

— Johnson, quoted in The New York Times (Feb. 16, 2003)

Marci Hamilton

On this date in 1957, Marci Ann Hamilton — litigator, legal scholar, child protection advocate and opponent of “extreme religious liberty” — was born in Dallas, Texas, to Carol and Bill Hamilton, a stay-at-home mom and a sales representative for a national firm.

After earning a B.A. in philosophy and English from Vanderbilt University in 1979, she earned master’s degrees from Penn State University in those subjects in 1982 and 1984, the year she married Peter Kuzma, a Ph.D. organic chemist. Hamilton’s interest in the crossover between philosophy, theology and existentialism attracted her to the work of philosophers like Kierkegaard and Nietzsche.

She then earned a J.D. in 1988 from the University of Pennsylvania Law School, where she was editor-in-chief of the Law Review. She clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor (one of her idols) and Judge Edward Becker of the 3rd Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals.

Hamilton is the Fels Institute of Government Professor of Practice and a Resident Senior Fellow in the Program for Research on Religion at the University of Pennsylvania. Previously she held the Paul R. Verkuil Chair in Public Law at the Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University in New York City. In 2016 she founded CHILD USA, a nonprofit academic think tank dedicated to improving laws and public policy to end child abuse and neglect.

She successfully challenged the constitutionality of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) at the Supreme Court in Boerne v. Flores (1997). She has represented numerous cities, neighborhoods and individuals dealing with state-church issues as well as claims under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act. Regarding Boerne (pronounced BUR-nee), Hamilton said, “I was essentially the only law professor in the country who was very publicly saying that extreme religious liberty was wrong. Most of the law professors were on the other side. (Omnia Magazine, University of Pennsylvania, May 21, 2020)

In the preface to God vs. the Gavel: The Perils of Extreme Religious Liberty (2014), a revision of Hamilton’s God vs. the Gavel: Religion and the Rule of Law (2005), she notes how after her Boerne victory (which Congress and states later got around by passing new RFRAs), she “was led on a journey into the underside of religion, because all the groups that lobby against religion sought me out. They earnestly and generously educated me about the facts of religiously motivated illegal behavior.”

Hamilton adds in the preface, “Ten years later, I am no longer shocked at the unacceptable behavior of too many believers, but I am even more determined that Americans learn about the dangers inherent in the religious liberty regime that was initiated in 1993 with the RFRA. The Framers called too much liberty ‘licentiousness.’ I simply call it extreme.”

In the Omnia interview, Hamilton said: “Working on all these issues on the opposite side of organized religion had never been part of any plan. My husband’s Catholic and I’m Presbyterian. We’re not atheists by a long shot. But when all the clergy sex abuse reporting started happening, I began getting calls from all over the country.”

She reached out to offer her help to plaintiffs’ attorney Jeff Anderson in 2011 in the wake of a Philadelphia grand jury report about clergy sex abuse. “I have a personal stake in this. My children are Catholic. My daughter was baptized by a pedophile priest. I have family pictures with a pedophile at one of the most important ceremonies of a child’s life. So I am in it, yes, in Philadelphia. Because it’s the only way to make this archdiocese do the right thing.” (Philadelphia Business Journal, March 27, 2013)

Hamilton has “profound contempt” for any institution or person covering up pedophilia or otherwise endangering children, e.g., denying them medical care due to religious beliefs. “I criticize the failure to protect children from sexual abuse wherever I see it, whether it is in a university, a private school or organization, or a public school. The whole culture needs to wake up and do better on this issue. The Catholic Church’s problem is that it is the largest institution in the world, and its victims have been coming out of the woodwork.” (Omnia, ibid.)

CHILD works to eliminate statutes of limitation so that abusers can be prosecuted no matter how long ago the crime occurred. Dozens of states have passed Child Victim Acts to enable that. Hamilton and co-counsel made history in March 2020 when they filed the first two lawsuits against the Church of Scientology for child sex abuse.

She received the 2015 Religious Liberty Award from the American Humanist Association and was the recipient in 2014 of FFRF’s Freethought Heroine Award. Her acceptance speech titled “Extreme Religious Liberty Is Tyranny” can be viewed or read here. Hamilton also wrote FFRF’s amicus brief before the Supreme Court in the Hobby Lobby challenge of the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate.

“The ‘Restoration’ in the title is a lie. It was not restoring anything that had been in place before. It was putting in place what the religious litigants had failed to obtain for years.”

— Hamilton, referring to the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, FFRF convention speech (Los Angeles, Oct. 24, 2014)

Frances “Poppy” Northcutt

On this date in 1943, Frances Marian “Poppy” Northcutt — computer engineer, attorney and women’s rights activist — was born in Many, Louisiana. She was raised in Luling, Texas, and as a teen was named Miss Watermelon of Luling. Her brother nicknamed her after reading Poppy: The Adventures of a Fairy, a 1934 children’s book. (Aviation Magazine International, March 1970) While the character Poppy was only 4 inches tall, Northcutt as an adult would top 5-foot-9.

After graduating with a mathematics degree from the University of Texas, she went to work as a 22-year-old “computress” (the actual job title) in 1965 at TRW, an aerospace contractor for NASA in Houston. In those days, classified ads had separate sections for male and female employment. Jo Ann Evansgardner and her husband, both later FFRF Life Members, successfully sued in 1969 to stop the practice.

Northcutt was the first woman stationed in NASA’s Mission Control. Her team designed the return-to-Earth trajectory for Apollo 8, the first manned mission to orbit the moon, and for missions through Apollo 13. Television broadcasts that showed her brought heaps of fan mail. ABC reporter Jules Bergman once asked about her potential to distract from the mission: “How much attention do men in Mission Control pay to a pretty girl wearing miniskirts?”

She answered: “Well, I think the first time a girl in a miniskirt walks into [Mission Control], they pay you quite a lot of attention, but after a while they become a little bit more accustomed to you and pay more attention to the consoles.” She told Teen Vogue in 2019 that “all women at that time, in all the places around the world, were living in a sea of sexism.”

In 1981 she graduated from the University of Houston law school while continuing to work as an engineer and as the city of Houston’s first women’s advocate, working to promote equal opportunity municipal employment and pay equity for women. She became the first prosecutor in the domestic violence unit in the Harris County district attorney’s office and worked with the nonprofit Jane’s Due Process to ensure legal protections for pregnant minors in Texas.

Northcutt is not a fan of religion, while not saying publicly what her personal beliefs are. On Oct. 3, 2019, she tweeted a USA Today story detailing the Catholic Church’s successful lobbying to limit lawsuits by survivors of clergy sex abuse. About Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s comment “The Problem is Not Guns, It’s Hearts Without God,” she tweeted in August 2019 that “I seriously doubt that most of the mass shooters are atheists. Show me the data, Governor.”

On May 22, 2020, she tweeted about several COVID-19 “superspreader events” at churches. “All this money to churches is appalling,” she tweeted on July 10, 2020. “They amass huge holdings free of taxes, litigate zealously to be free of following laws with which they disagree, and then my tax dollars go to them!”

“I think we share the same opponents because both the trans cause and the feminist cause challenge sex roles, and sex role stereotyping is central to most fundamentalist religions. We challenge what our opponents view as ‘natural’ and ‘necessary’ and ‘God-ordained.’ I think they are very afraid of us because we cast doubt on things they view as certainties. And if one certainty bites the dust, then what else might fall?”

— Northcutt, on how people opposing rights for transsexuals also oppose reproductive choice; The Conversation Project (Nov. 30, 2015)

Paul Morantz

On this date in 1945, attorney Paul Robert Morantz, renowned for litigating against religious cults, was born in Los Angeles to Jeanette (Kates) and Nathan Morantz. His father owned a meatpacking business and his mother was a homemaker.

His skepticism started early, Morantz wrote in his 2012 memoir “Escape: My Lifelong War Against Cults.” He remembered listening when he was 12 to the rabbi during Passover services talking about leaving an offering outside the home for a biblical angel. His memoir recounted how he objected to his parents after they caught him leaving the house with a baseball bat: “I can’t believe you are all celebrating this. I can’t accept the idea that God would murder innocent children. I’m going outside to hide and when the Angel of Death comes for his wine and matzo, I’m going to bash him so he won’t ever harm a child again.”

After high school he served six months in the Army Reserves, then attended Santa Monica City College. Transferring to the University of Southern California, he studied journalism and covered sports for the campus Daily Trojan, graduating in 1968. Journalism was his true love but, encouraged by his father, he went on to earn a USC law degree three years later.

In 1974 he took on the case of Skid Row alcoholics picked up off the street in downtown L.A. and effectively sold to mental institutions. They were drugged to the point of incoherence so the facilities could fraudulently bill Medicare. He spent over two years winning a settlement for the victims. He really burst into public consciousness while successfully representing clients suing Synanon, a quasi-religious cult with a paramilitary wing. Founded by Charles Dederich as a drug and alcohol rehabilitation center in Santa Monica, it would grow into an organization with adherents nationwide and overseas.

About three weeks after winning a $300,000 settlement against Synanon in 1978, Morantz opened his mailbox and was bitten by a rattlesnake, 4½ feet long, with the rattle removed. Dederich and two men he hired to place the snake were convicted. One was 20-year-old Lance Kenton, the son of swing band leader Stan Kenton. The judge called the attack an “aberration” and imposed light sentences due to Synanon’s history of helping addicts. Dederich received five years’ probation.

Morantz had learned that self-help guru Werner Erhard, the founder of Erhard Seminars Training (EST), was lobbying a small town to let him “train” its employees. Morantz intervened and turned the town against him. In 1978 he tried unsuccessfully to win the release of a client’s son from the People’s Temple, whose leader, Jim Jones, later led several hundred of his followers in a mass suicide in Guyana.

He represented 40 ex-followers of the Center for Feeling Therapy, a New Age movement that used “sluggo therapy” in which members beat each other, supposedly to release suppressed anxieties. He also helped ex-members of the Rev. Sun Myung Moon’s Unification Church in a case in which the California Supreme Court ruled in 1988 that religious organizations could be sued for fraud. Scientology, Hare Krishnas, followers of swami Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, among others, felt the sting of his litigation.

Twice over two decades, he successfully went after psychologist/minister John Gottuso, accused of sexually abusing his female followers and even the daughters of the women. In another case, he helped bring to justice a psychotherapist who converted his patients to Hasidic Jews so he could become their rabbi and control their lives.

He married Maren Elwood in 1984; they divorced in 1988. Their son, Chaz Morantz, was an engineer on the NASA team that built the Mars rover Curiosity, still operating as of this writing in December 2022 after landing in 2012.

All the while, Morantz wrote extensively about the cases he was involved in, along with a broad range of cultural and political topics, including jaundiced views of Donald Trump. They are archived at paulmorantz.com. He died at age 77 at home. (D. 2022)

PHOTO: Morantz in 2003 outside his home in Pacific Palisades, Calif.

"Whether we worship single or multiple deities, Mother Nature or the Church of the Divine Meatloaf, our populace seems hard-wired to believe in some greater force. When groups use the power of peer pressure and brainwashing to control people and make them surrender their autonomy, their money or their moral compass, I feel compelled to step in."

— "Escape: My Lifelong War Against Cults" by Paul Morantz with Hal Lancaster (2012)

Theodore Schroeder

On this date in 1864, Theodore Schroeder was born on a farm near Horicon, Wisconsin. Because his parents “intermarried” (one was Lutheran, the other Catholic), they were disowned by their families. His father became an agnostic, and Schroeder was also influenced by the legacy of the freethinking German immigrants who came to Wisconsin after the failed 1848 revolution. He took the injunction to “go west, young man” to heart and traveled for about a decade, taking odd jobs to support himself.

In 1882 he entered the University of Wisconsin, studying engineering, then earning a law degree in 1889. He practiced law for 10 years in Salt Lake City, making a study of Mormonism. Schroeder worked for statehood for Utah, but grew alarmed at the Mormon theocratic hold, as well as the practice of polygamy, which he termed “sanctified lust.” In 1900 he moved to New York and formed the Free Speech League (a precursor to the American Civil Liberties Union) with Lincoln Steffens and other progressives.

By 1908, when he moved to Connecticut, Schroeder was focusing his activism against religionist Anthony Comstock and the Comstock laws, which suppressed free speech relating to sexual matters, especially discussion of birth control. He helped defend his friend and anarchist Emma Goldman at her Denver trial, as well as many others prosecuted in blasphemy or obscenity cases, including progressive ministers. He wrote Constitutional Free Speech Defined and Defended in an Unfinished Argument in a Case of Blasphemy (1919).

He turned his attention to what he called the erotogenetic theory of religion, which he developed after observing Mormonism. William James and others discredited the concept, but he found allies in Havelock Ellis and Chapman Cohen. He also worked with the National Liberal League, which became the American Secular Union.

Schroeder became the victim of the censorship he had worked against his entire life when his will, instructing that his works be published as a collection, was found invalid by the Connecticut Supreme Court. The court called his freethought writing “obscene,” offensive to religion and of no social value. Judge O’Sullivan wrote, “The law will not declare a trust valid when the object of the trust, as the finding discloses, is to distribute articles which reek of the sewer.” (D. 1953)

"The freethinker has the same right to discredit the beliefs of Christians that the Orthodox Christians enjoy in destroying reverence, respect, and confidence in Mohammedanism, Mormonism, Christian Science, or Atheism."

— Schroeder, "Constitutional Free Speech Defined and Defended in an Unfinished Argument in a Case of Blasphemy" (1919). "The Encyclopedia of Unbelief"

Charles Bradlaugh

On this date in 1833, England’s best-known proponent of atheism, reformer Charles Bradlaugh, was born in London. He left school at age 11 to earn his living. When he announced his freethought views, he was forced to leave his family home and found support among other freethinkers, including the children of oft-jailed publisher Richard Carlile. Bradlaugh worked as a coal merchant. After joining the army, he worked as a solicitor’s clerk, learned the law and became an attorney.

He wrote and lectured about freethought under the pseudonym “Iconoclast.” Bradlaugh briefly became editor of the freethinking bi-weekly periodical The Investigator in 1858. By the time he became co-editor of the National Reformer in 1860, he was a famed social reformer and orator, known in England and abroad. In 1866 he founded the National Secular Society. Bradlaugh had two daughters and one son with his wife, whose serious drinking problem broke up the family in 1870.

Bradlaugh’s challenge in 1868-69 of the Security Laws, inhibiting distribution of controversial periodicals, brought their repeal. He also championed land reform. In 1876, he and colleague Annie Besant were prosecuted for “obscenity” for republishing a birth control booklet, The Fruits of Philosophy, by American doctor Charles Knowlton. After a long trial, the pair were convicted and faced jail and fines but were freed on a technicality. Bradlaugh was urged to run for Parliament in 1868, placing fifth. He ran several times before winning in 1880 but was refused seating because he would not take the religious oath.

Bradlaugh was reelected four times before finally prevailing in his fight to be seated in 1886, but the legal fight had drained him financially. Bradlaugh persuaded Parliament to pass a bill permitting the right to affirm in 1888. Bradlaugh lectured three times in the U.S. in the 1870s and was warmly received in India during his 1889 visit. His only surviving child, Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner, took up the freethought/reform cudgels, also defending her father’s reputation from numerous “death-bed conversion” fables. D. 1891.

"I maintain that thoughtful Atheism affords greater possibility for human happiness than any system yet based on, or possible to be founded on, Theism, and that the lives of true Atheists must be more virtuous — because more human — than those of the believers in Deity, the humanity of the devout believer often finding itself neutralized by a faith with which that humanity is necessarily in constant collision.”

— Bradlaugh, "A Plea for Atheism" (1929)

Robert R. Tiernan

On this date in 1933, freethinking attorney Robert Reitano Tiernan was born in Norwood, N.Y., to Albert and Grace (Reitano) Tiernan. Raised as a Catholic and later rejecting it, he graduated from LeMoyne College, a Jesuit school in Syracuse, and the Boston College School of Law. The day after law school graduation he was drafted into the U.S. Army, serving two years at Fort Dix, N.J. He helped provide security for presidential candidate John F. Kennedy.

Tiernan practiced law for 20 years at the D.C. firm of Keller & Heckman in Washington and later specialized in constitutional law in Denver. After the tragic accidental death of his younger son Timothy in 1983, he spent three years successfully lobbying for mandatory installation of vehicle airbags.

A longtime FFRF member and supporter, Tiernan headed the Denver chapter and was FFRF’s 2001 Freethinker of the Year for his legal contributions over the years. He stopped a 53-year violation involving a major taxpayer subsidy of an annual Easter service at the publicly owned Red Rocks Amphitheatre near Denver and defended pro bono a freethinker accused of “blasphemy” for removing a religious cross illegally placed in a public right-of-way.

He won a partial victory in 1998 in an FFRF lawsuit when a federal court ordered removal of religious phrases and several images from a shrine built to commemorate the Mass said by Pope John Paul II in 1993 in Cherry Creek State Park outside Denver. “We object to the holding of religious ceremonies on public property, but that was a battle that was lost 25 years ago when the pope was allowed to say Mass on the Mall in Washington, D.C.,” Tiernan said at the time. (D. 2019)

"It's a shame that the judicial system, and especially the current U.S. Supreme Court, has tinkered so much with [the Establishment Clause] because the admonition is simple: There shall be no establishment of religion. The idea of 'accommodating' religion, which is the current rage with the judiciary, absolutely contradicts this clear and simple language and demeans our Constitution."

— Tiernan, accepting FFRF's 2001 Freethinker of the Year award in a speech titled "Blasphemy 101"

Thomas Gore

On this date in 1870, Thomas Pryor Gore was born near Embry, Miss. As a boy he permanently lost sight in both eyes in separate accidents. Gore took a great interest in politics as a teenager and developed exceptional public speaking skills. He taught school before attending law school at Cumberland University in Tennessee. After being admitted to the bar in 1892, he joined the national Populist movement and moved to Texas to practice law.

After the Populist movement began to decline nationwide with the defeat of presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan in 1900, Gore became a Democrat and moved to Oklahoma to continue practicing law. He was elected to the Territorial Council in 1903 and, when Oklahoma became the 46th state in 1907, to the U.S. Senate. A powerful figure in the party, he served on the Democratic National Committee. He helped President Woodrow Wilson make sweeping changes to the party and turned down a cabinet position so that he could keep his Senate seat.

Gore advocated for women’s suffrage and the interests of farmers and strongly opposed railroad monopolies. His opposition to American involvement in World War I and later opposition to the formation of the League of Nations cost him his personal friendship with Wilson and the 1920 election. He successfully ran for the Senate again in 1930, when he openly criticized President Herbert Hoover’s Depression recovery policies and later opposed many of FDR’s New Deal programs. He was the only senator to vote against the Works Progress Administration. He lost his Senate seat in the election of 1936.

Gore married Nina Belle Kay in 1900 and they had two children, one of whom was Nina S. Gore, the mother of historian and author Gore Vidal. Vidal recalled that his grandfather was talked into being photographed in a Methodist Church on Sunday. Gore asked him, “ ‘Grandpa, what are we doing in this thing?’ He said, ‘Well, my boy, you may ask what we’re doing here. I’m getting votes, I don’t know about you.’ ” Vidal said Gore, asked once about the religious differences between himself and his wife, replied, “Well, one Sunday we don’t go to her church and the next Sunday we don’t go to mine.” (The Humanist, Dec. 28, 2009)

He once famously noted of his adopted state, “I love Oklahoma. I love every blade of her grass. I love every grain of her sands. I am proud of her past and I am confident of her future.” Gore died at age 78 and is buried in Oklahoma City. In September 2010, FFRF posted a billboard in Tulsa which read: “Atheism is OK in Oklahoma: Saluting Gore — First Atheist Senator.” (D. 1949)

“[H]e was a dedicated atheist. Imagine, he was senator for over thirty years in Oklahoma, a hotbed of the Lord Jesus, and they never found out. He never tried to hide it.”

— Vidal on his grandfather, interview in The Humanist (Dec. 28, 2009)

Edward Tabash

On this date in 1950, attorney Edward “Eddie” Tabash, advocate for state-church separation and an atheist, was born in Los Angeles. His father was a rabbi from Lithuania and his mother was an Auschwitz survivor from Hungary. He remembers adults telling him at age 7 at a Passover seder how the god of the Old Testament rescued Jewish slaves from Egypt, prompting him to ask why that same god allowed the Holocaust. The adults responded with an embarrassed silence.

As a young adult he sought spiritual comfort from New Age meditation and similar techniques. He graduated magna cum laude from UCLA in 1973 and in 1976 from Loyola Law School in Los Angeles, where he specializes in constitutional law and criminal defense.

For two decades, Tabesh was the primary speaker and debater for the California Abortion and Reproductive Rights Action League. He represents the atheist viewpoint in formal debates with Christian apologists and is a longtime FFRF supporter and Life Member. As of this writing in 2021, he is board chair of the Center for Inquiry.

Asked in a debate where morality comes from, he answered: “It develops from compassion, from mercy, and from understanding the plight of the human condition. … [T]he superiority of the atheist-derived compassion is evidenced by the fact that we don’t talk about how justified it is for people to go to hell forever just because they made the wrong theological choice. That, to me, is the most damning, immoral obscenity articulated by Christians.” (Debate at UC-Davis, Dec. 1, 1993)

Tabash seeks equality for nonbelievers and believers but has expressed concern about how fundamentalist beliefs of all kinds have been used throughout history to deny women equality: “No person should lose her or his freedom because of someone else’s religious beliefs.” He said the same is true about LGBTQ+ discrimination: “There is not one proposed piece of legislation that would deny gays and lesbians equal rights that is not grounded in religious dogma.” (“Point of Inquiry” podcast, May 4, 2006)

He lives in Pacific Palisades, a coastal Los Angeles community.

“I submit that the Christian God is an unproven myth.”

— Tabash during "Does God Exist?" debate with Christian apologist Greg Bahnsen at UC-Davis (Dec. 1, 1993)

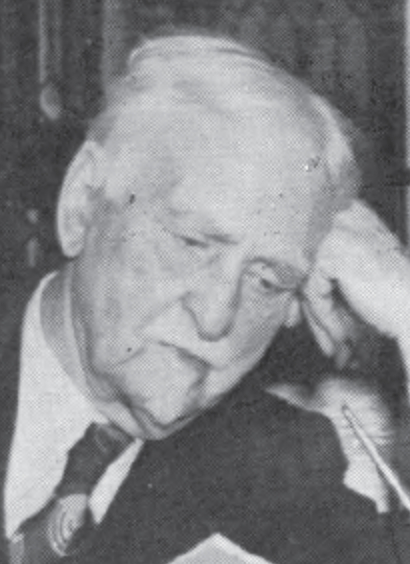

Leo Pfeffer

On this date in 1910, Leo Pfeffer, a leading legal proponent in the mid-20th century of separation of church and state, was born in Austria-Hungary. He came to the U.S. at age 2 with his family. He was raised a Conservative Jew and remained observant, while later quipping that “the Orthodox consider me to be the worst enemy they’ve had since Haman in the Purim story!” (See featured quote below.)

After practicing law and working as associate general counsel for the American Jewish Congress, Pfeffer became a professor of political science in 1964 at Long Island University, where he taught until his retirement in 1980. He was the American Humanist Association’s Humanist of the Year in 1988.

His masterpiece, Church, State, and Freedom (1953), is the ultimate sourcebook for the history of the evolution of the principle of the separation of church and state. His eight books include The Liberties of an American: The Supreme Court Speaks (1956), Religious Freedom (1977) and Religion, State & the Burger Court (1985). Pfeffer called himself a “strict separationist in contrast to what is called ‘accommodationist.’ ”

Pfeffer pleaded “partly guilty” to inadvertently perpetuating the myth that “secular humanism” is a religion. In defending nontheist Roy Torcaso before the U.S. Supreme Court in Torcaso’s case challenging a religious test in Maryland to become a notary public, Pfeffer wrote that “there are religions which are not based on the existence of a personal deity.” His examples: Ethical Culturists, Buddhists and Confucians.

“My good friend Justice Black thought that wasn’t good enough. He put in the secular humanists. Who told him secular humanism? I didn’t have it in my brief! I couldn’t sue, because you can’t sue a justice of the Supreme Court. But since then I rued the day.” (Freethought Today, Jan/Feb 1986)

He married Freda Plotkin in 1937. They had two children, Alan Israel and Susan Beth. (D. 1993)

“I believe that the history of the First Amendment and also the Constitution itself, which forbids religious tests for public office, have testified to the healthful endurance of a principle which is the greatest treasure the United States has given the world: the principle of complete separation of church and state. I’m here to tell you that that principle is endangered today. "

— Pfeffer speech to FFRF's national convention in Minneapolis (Sept. 29, 1985)

Wendy Kaminer

On this date in 1949, Wendy Kaminer was born. She earned her undergraduate degree from Smith College in 1971 and went on to graduate from Boston University Law School in 1975. Kaminer worked as a criminal defense attorney for the New York Legal Aid Society (1977-78), as a staff attorney for the New York City Mayor’s Office and as a professor at Tufts University (1988-90).

In 1991 she switched her focus from law to journalism when she became a contributing editor for The Atlantic, although she often writes about legal issues. She is also a senior correspondent for The American Prospect.

She is the author of eight books, including I’m Dysfunctional, You’re Dysfunctional: The Recovery Movement and Other Self-Help Fashions (1992), Sleeping with Extra-Terrestrials: The Rise of Irrationalism and Perils of Piety (1999) and Free For All: Defending Liberty in America Today (2002). Kaminer was awarded the Extraordinary Merit Media Award from the National Women’s Political Caucus in 1993 and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1993.

Kaminer is an outspoken agnostic who uses her journalism platform to speak up about atheism and state/church issues. Many of her articles discuss the harm of religion’s influence on politics, civil liberties, psychology and the law. In “The Last Taboo: Why America Needs Atheism,” published in The New Republic in 1996, Kaminer wrote: “Atheists generate about as much sympathy as pedophiles. But, while pedophilia may at least be characterized as a disease, atheism is a choice, a willful rejection of beliefs to which vast majorities of people cling.”

Kaminer was the recipient in 2000 of FFRF’s Freethought Heroine Award. She married Woody Kaplan, a civil liberties activist and chairman of the advisory board of the Secular Coaltion for America in 2001. He died of cancer in 2023.

"I don't care if religious people consider me amoral because I lack their beliefs in God. I do, however, care deeply about efforts to turn religious beliefs into law, and those efforts benefit greatly from the conviction that individually and collectively, we cannot be good without God."

— Kaminer, “No Atheists Need Apply,” The Atlantic (Jan. 13, 2010)