By Robert R. Tiernan

I wrote the article below in September 1983, eight months after our son Tim’s death.

Tim was severely brain-injured on the night of August 7, 1981. We were driving to our family vacation home in West Virginia when the car left the road and struck a tree. Tim was hospitalized in Washington, D.C., until March of 1982, at which time he was transported by air ambulance to a facility for brain-injured people in Erie, Penn. He died on January 24, 1983, 536 days after he was injured. Tim was comatose for that entire period of time.

After his death I left the practice of law (I was a partner in a medium-sized firm in D.C.) and advocated mandatory installation of air bags for the next three years. I then left the D.C. area and settled in Denver with my other son.

I can’t tell you how painful Tim’s predicament was, especially for him. To be frank, I hoped he wasn’t the least bit cognitive because, if he was, imagine how he must have felt being so helpless. Most people don’t understand what life in a coma is. Endless torture. Tubes, ice blankets to reduce a fever, operations, hourly suctioning of one’s lungs, etc.

Timmy was the youngest of our three children. My life will never be the same as it was before he was hurt, but life does go on. I have the utmost admiration for the husband of Terri Schiavo. Yes, maybe he does have a girlfriend and has had children by her. But he stood by his wife for 16 years and that’s what is important. I can’t begin to imagine how he has survived all this. For Bush and his political cronies to intervene is shameful beyond description. It’s a good thing I don’t believe in hell, because that is surely where these sanctimonious good-for-nothings would go if there was one.

* * *

In the recesses of a building in Erie, Penn., lie some 70 or more boys and girls. They are not dead, but are they alive?

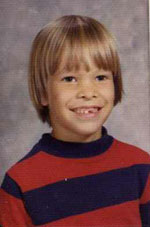

Most of these children, whose pre-injury pictures line the walls, were active, handsome, full of life. Pictures above one bed show a pretty 15-year-old cheerleader; next door, the high school graduation picture of the captain of his football team; his roommate, our son Timmy, at his 13-year-old birthday party, blowing out candles with his friends.

Looking at the reality below the photographs, the cheerleader has be-come a grimaced, atrophied, pathetic looking parody of herself. The 18-year-old former athlete lies, eyes fixed at the ceiling, blinking randomly, otherwise motionless. Timmy, now 15, lies on his side seeming to stare out in space, silent too. He has been in a coma for a year and a half. His muscles have turned to jelly; his head is deeply depressed on the left side because a portion of the skull has been removed to relieve pressure on his brain; he has a tube penetrating the abdomen into his stomach to provide food; his windpipe has been cut open so that he may breathe; every hour, on the hour, a nurse arrives to inject a suction tube into his lungs to remove mucous and fluid. If you look at the pictures of Timmy on the wall, you won’t recognize him as the same person.

Timmy’s mother sits there comforting her son. His sister and brother pace in and out of the room, torn between the conflict of wanting to be with their stricken brother and, yet, not being able to cope with the grief of seeing him as he is now.

And, oh, the questions. Does he know anything? Oh, yes, we hope–that means maybe some day he can wake up and this horrible nightmare will be over. But, no–how could we stand to think this person we love so much might wake up and then be condemned to lie there paralyzed, knowing that he is trapped forever–a prisoner of his own body?

All the other questions. What if he never gets better? How long must he suffer? How long must we suffer? Who is going to pay for the cost of all this? What if he outlives me? Who will take care of him then? The conflict of emotions is overwhelming; now of fear, then of hope, later of sadness, even anger–anger that this once active child of ours won’t talk to us, won’t tell us what he wants. He just lies there in his own world; a world we cannot enter.

This is life in a coma. And, as the minutes, hours, days, and months pass by, we cling to hope like survivors of a sinking ship until, finally, we lose all expectations. Perhaps a glimmer of hope, irrational as that is, remains–but what is it we expect? Nothing. Life seems useless. There is nothing to look forward to anymore.

A grammar school photograph of Timmy Tiernan

|

I go to the waiting room. There is a commercial featuring the president of Chrysler Corporation, extolling the virtues of his new line of flashy, turbo-charged cars. Later on, we are told in a General Motors ad how they “sweat the details.” A news report concerns the White House’s declaration in favor of prayer in schools. The next report concerns a heroic effort, including the President’s personal intervention for which he proudly takes credit, to find a liver donor to save a three-year-old child. Astonishingly, I find myself feeling envious of this unfortunate child and her parents. They have hope; we don’t.

We know, now that we have reason to know, that the car in which our son was so mortally wounded did not have an air bag. We are told that, yes, an air bag would have prevented all this. We know that despite the president’s “religious” convictions, he has cut back on financial aid for the needy like our Tim. It costs too much. It would cut too deeply into the defense budget. It might eliminate the $105 million set aside to develop a more lethal nerve gas. So the technology of this wonderful country keeps these once fatally injured people alive–then ignores them.

We are told that the government won’t require the auto companies to make cars safer by installing air bags. It is not consistent with the new and popular wave of “deregulation.”

So, we survive–alone, isolated. The TV blare reminds me of the song from “Midnight Cowboy”–“Everybody’s talkin’ at me but I can’t hear a word they’re sayin’.”

We are hardly able to help each other: Timmy’s mother, his sister, his brother. Each of us has to deal with our own special hurt–terror is a better way of describing it. Our lives seem doomed to teetering on the edge of an eternal precipice.

One night, we are awakened by a phone call. It is Timmy’s doctor in Erie, Penn. Timmy has suffered respiratory arrest and is unable to breathe on his own. From a distance of 350 miles away, his mother and I tell the doctor no resuscitator–no heroic measures. Be merciful–let our son go in peace. The doctor agrees. So, a 15-year-old child–with no loved one nearby–dies alone. By sheer coincidence, his mother, who has sat at his bedside for 18 months, cannot be with him at the end. But was it coincidence? Timmy was a wonderful and sensitive boy. Perhaps he chose to die in our absence to spare us the final blow of having to see it. Perhaps it gave him a certain dignity for, after all, isn’t death a lone and singular act? Timmy was always a very brave person too.

The last time we saw Timmy, he lay on a slab–dead. He was pale and lifeless. That was what remained of our son. His mother and I turned to each other and embraced. There was relief involved–great relief. Our limbo, Timmy’s limbo, was over. I never felt so bad for another human being as I felt for his mother at that moment. It was not a desperate sadness. But it was deeper and, in a mysterious way, gentler than I had ever known or ever want to know again.

My life will never be the same. As the days, months, and years go by, the pain subsides. That pain was so deep and intense, I could actually measure it diminishing day by day.

The good memories begin to emerge. And, yes, there were many of those. But Timmy is gone forever. All our dreams for him are shattered–all the plans he had, the promise he held–gone. What finality!

For the rest of our days on this earth, we are to be denied the reality of Tim. I now know for whom the bell tolls. For us, and, yes, for you, the world is, and always will be, diminished. A child of this universe is gone.

Robert R. Tiernan, an attorney, is a Foundation member and activist. He was successful in lobbying for installation of air bags in new cars.