atheists

Dax Shepard

On this date in 1975, Dax Randall Shepard was born in suburban Detroit, the son of Laura LaBo, who worked at General Motors, and David Shepard, a car salesman. He was named Dax for Diogenes Alejandro Xenos, the wealthy playboy in Harold Robbins’ novel “The Adventurers.” His parents divorced when he was 3.

After high school graduation he enrolled in a school operated by the Groundlings, an improvisational and sketch comedy troupe based on Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles. He’d always known he could be funny but had stage fright about doing stand-up in Detroit so he moved to California, thinking “that commitment would force him to do it.” (2014 interview with Marc Maron) He attended Groundlings classes while enrolled at UCLA, where he graduated magna cum laude with a B.A. in anthropology in 2000.

In 2003 he joined the cast of “Punk’d,” a hidden camera, practical joke reality show created by Ashton Kutcher and Jason Goldberg that aired on MTV. In 2004 he starred in “Without a Paddle” with Seth Green and Matthew Lillard, followed by roles in “Employee of the Month” with Dane Cook and Jessica Simpson (2006), “Idiocracy” (2006), “Let’s Go to Prison” (2006) and “Baby Mama” (2008) with Tina Fey and Amy Poehler.

In 2010 he wrote, directed and starred in the low-budget mockumentary “Brother’s Justice” and had a supporting role in the rom-com “When in Rome, which starred his future wife Kristen Bell. From 2010-15 he played Crosby Braverman in the NBC drama “Parenthood.” His other movies since then as of this writing include “Hit and Run” with Bell and Bradley Cooper (2012), “The Judge” (2014), “CHiPs” and “El Camino Christmas” (2017).

His ad with Bell for the Samsung Galaxy Tab S tablet in 2014 garnered over 20 million YouTube views. In 2018 he launched the podcast “Armchair Expert” with co-host Monica Padman. It features the lives of celebrity guests and was the most popular new podcast on iTunes in 2018.

Shepard and Bell started dating in 2007 and got engaged in 2010 but refused to marry until California legalized same-sex unions, which happened in 2013. They have two daughters, Lincoln and Delta. He’s an atheist and Bell is also nonreligious. In 2013 she told Australian Women’s Health that they start their days with a 20-minute transcendental meditation session, sometimes holding hands. On his Twitter account, he describes himself as “Humanist. Comedic actor who is light on both comedy and acting. Alt Centrist.”

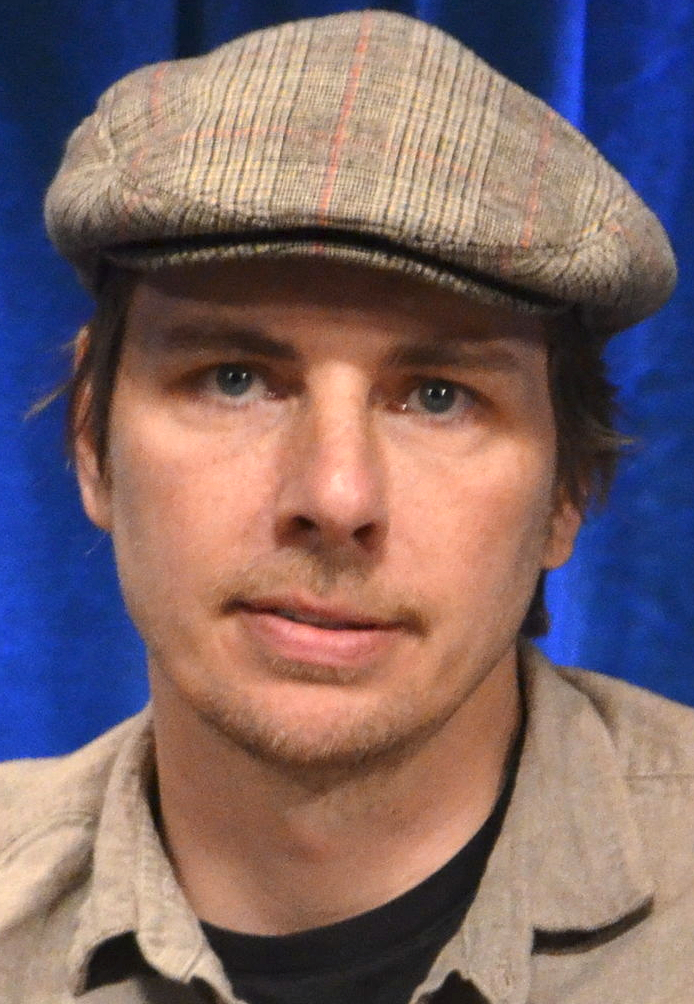

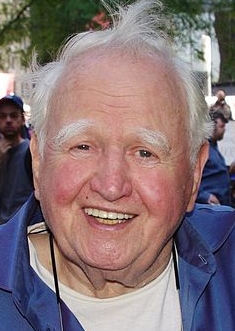

PHOTO: Shepard at PaleyFest 2013 in Los Angeles; photo by Genevieve under CC 2.0 Generic.

“I’m an atheist. Slow your roll :)”

— Shepard tweet replying to @JusPressPlay @PerezHilton (March 14, 2017)

Sebastian Junger

On this date in 1962, journalist and filmmaker Sebastian Junger was born in Belmont, Mass., to painter Ellen Sinclair and physicist Miguel Chapero Junger, who emigrated to the U.S. from Germany in 1941 because of his paternal Jewish ancestry. The younger Junger said he was raised in “a very rational household.” In a 2016 New York Times interview, he said, “I grew up with parents who were essentially antireligious, and so I never attended church. John Stuart Mill’s ‘Utilitarianism’ gave me the kind of ethical guidance that every person needs — religious or otherwise.” He studied cultural anthropology in Connecticut at Wesleyan University, which became independent of the Methodist Church in 1937, and graduated in 1984.

He started working as a freelance journalist while taking other jobs to support himself, later successfully selling pieces to publications like Harper’s, The New York Times Magazine, Vanity Fair, National Geographic Adventure, Outside and Men’s Journal. Researching hazardous jobs like commercial fishing led to his first book, The Perfect Storm: A True Story of Men Against the Sea (1997), which became a bestseller and a movie in 2000 starring George Clooney and Mark Wahlberg. Fire (2001) was a nonfiction collection about more dangerous pursuits — diamond mining, firefighting, peacekeeping in Kosovo and guerrilla warfare in Afghanistan. The previous year he had received a National Magazine Award for his Vanity Fair piece “The Forensics of War.” He received the 2007 Winship/PEN Award for A Death in Belmont, a book about the 1963 rape and murder of Bessie Goldberg.

He and British photographer Tim Hetherington teamed up on the award-winning “The Other War: Afghanistan,” shown on ABC’s “Nightline” in 2008. Junger’s book War (2010) revolved around a U.S. Army airborne platoon in Afghanistan. He and Hetherington co-directed a related documentary film, “Restrepo,” nominated for a 2009 Academy Award. Three documentaries about war and its aftermath followed: “Which Way Is The Front Line From Here?” (2013, about Hetherington’s 2011 death while covering the Libyan civil war), “Korengal” (2014) and “The Last Patrol” (also 2014). Another book was published in 2016, Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging.

Hetherington’s death made Junger question his own willingness to put himself in harm’s way to get the story and helped him decide he’d had enough. “I suddenly was realizing the effect of Tim’s death on everyone he loved, including me, and I just didn’t want to risk doing that to everyone I love.” (Cultist, 2013.) During a 2014 ethics panel discussion hosted by the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, he was asked if he was an atheist in a foxhole and answered, “As an atheist, I think about that phrase and I think, what is it really about an artillery bombardment that leads you to the conclusion that God is involved in this? I really see it the other way around: Clearly, God has nothing to do with what’s going on today.” Asked a similar question in a 2016 C-SPAN2 interview about there being no atheists in foxholes, he said, “I know empirically that’s not true.”

Junger married Daniela Petrova in 2002. They divorced in 2014. As of this writing, he lives in New York City and Cape Cod, Mass.

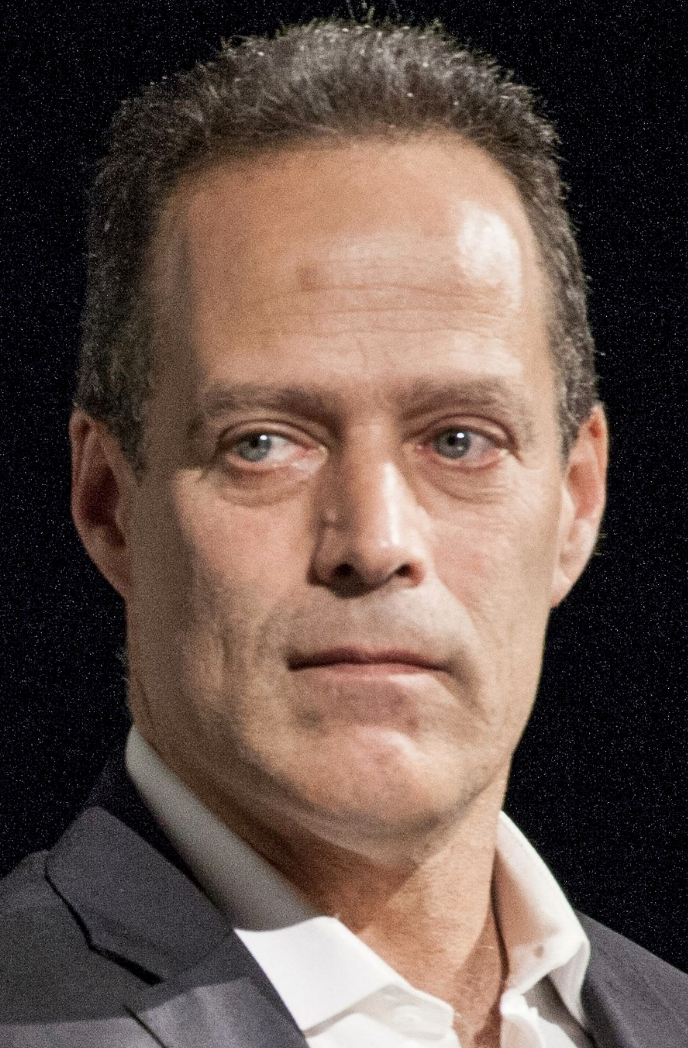

PHOTO: U.S. National Archives, public domain photo, 2013

“The reason I think I am an atheist is because I haven’t encountered a tangible reason to believe in God.”

— Sebastian Junger interview, C-SPAN2 "Book TV" (July 3, 2016)

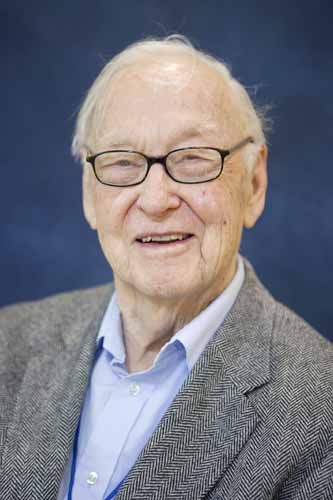

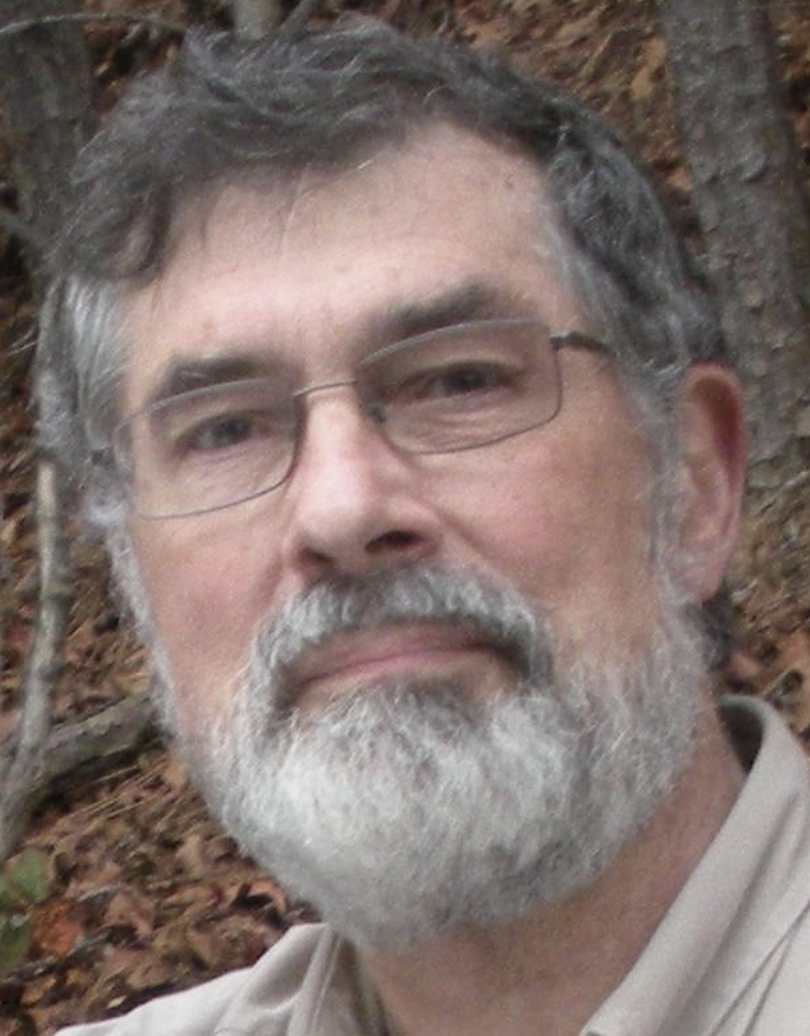

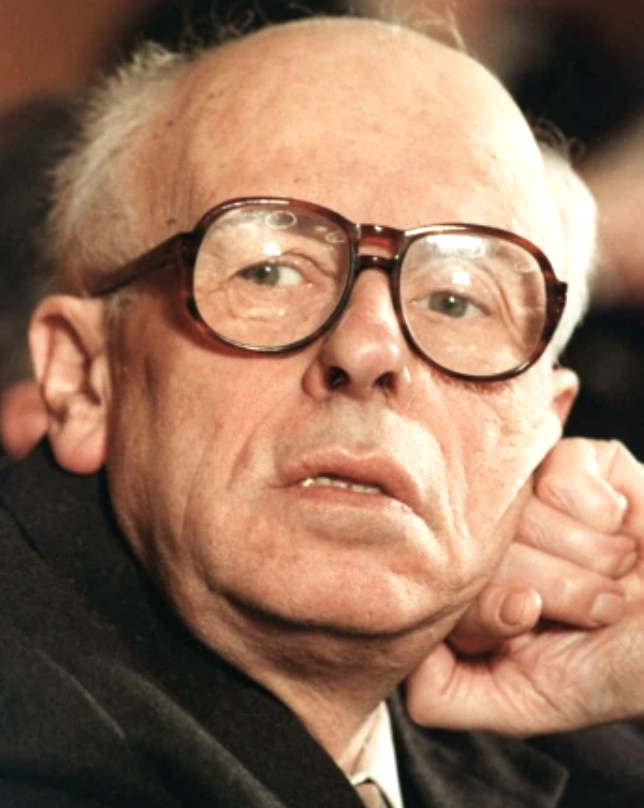

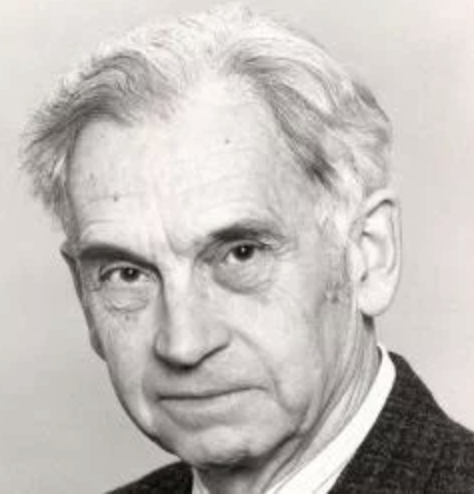

James F. Crow

On this date in 1916, world-renowned evolutionary biologist and population geneticist James Franklin Crow was born in Phoenixville, Pa. Crow grew up in Wichita, Kansas. “The Quaker Church in Wichita was an interesting mixture. I grew up in it and was a regular attender. My father and mother both were very serious about their religion,” Crow stated in the Oral History of Human Genetics Project in 2005, adding, “My own views are atheistic, but I don’t go around preaching atheism. You don’t get very far trying to do this.”

He received his bachelor’s degree from Friends University. In 1941, Crow earned his Ph.D. in genetics from the University of Texas. Crow began his teaching career at Dartmouth University, where he taught until 1948. He then joined the faculty at the University of Wisconsin, where he remained until his retirement. Crow’s research primarily focused on the field of population genetics. He also loved teaching, and authored two undergraduate textbooks on evolution. Crow met his wife, Anne Crockett Crow, when both were members of the student orchestra at the University of Texas (he played the viola, she played the clarinet).

He was a Fellow of the Royal Society of London and the Japan Academy, a member of the American Philosophical Society, the World Academy of Art and Science, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the National Academy of Medicine and the National Academy of Sciences, where he has chaired several committees, including one to study forensic uses of DNA fingerprinting. That committee’s report helped legitimize use of DNA testing in court. In addition, he was a prolific researcher whose ideas strongly influenced biological science throughout his career.

The gentle Crow, beloved by his students, colleagues and his community, was a Lifetime FFRF Member. He spoke at age 94 at FFRF’s 2010 national convention in Madison, Wis., about evolution and religious belief. He played viola in the Madison Symphony Orchestra for many years, performing a concert to celebrate his 90th birthday. In 2009 the James F. Crow Institute for the Study of Evolution was established at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. (D. 2012)

“My main personal reason for nonbelief is: Why would an all-powerful and especially benevolent creator permit so much sin and suffering?”

— James F. Crow, remarks, 2010 FFRF national convention

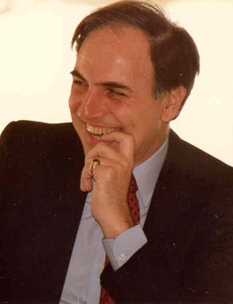

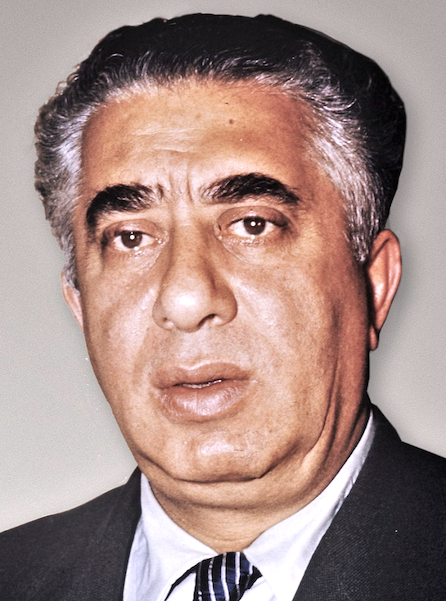

Sherwin Wine

On this date in 1928, Sherwin T. Wine was born in Detroit, Mich. He received his bachelor’s degree in philosophy from the University of Michigan, and returned for his master’s degree in philosophy in 1951. Wine attended Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati and was ordained as a rabbi in 1956. He worked as a U.S. Army chaplain in Korea (1957–58) and an assistant rabbi at Temple Beth El in Detroit (1958–60). Wine wrote many books, including Judaism Beyond God (1985) and Staying Sane in a Crazy World (1995). He lived with his partner, Richard McCains, until Wine’s death in 2007 in Morocco from a car accident.

Born to Conservative Jewish parents, Wine began questioning the idea of a god at Hebrew Union College and gradually lost his faith. He told Time magazine in 1965: “I am an atheist,” adding, “I find no adequate reason to accept the existence of a supreme person.” (Quoted in The New York Times, July 25, 2007.) Wine’s lack of belief led him to consider the concept of Humanistic Judaism, which rejects belief in God while maintaining secular Jewish traditions, culture and ethics.

“Theological beliefs have nothing to do with Jewish identity. The Jewish people encompass theists and atheists,” Wine explained in his book Celebration (2003). He elaborated on the beliefs of Humanistic Judaism: “Humanists know that they have the right and the power to be the masters of their own lives, that they have the strength to confront the world as it is and not as fantasy makes it appear, and that they have the opportunity to serve the future and not the past.”

Wine established the Birmingham Temple in 1963 in Farmington Hills, a suburb of Detroit. At the temple, which he worked at until his retirement in 2003, Wine performed services with no mention of God, replacing prayers with poetry and Torah readings with speeches on history. Humanistic Judaism is now practiced worldwide. (D. 2007)

“If I were a CEO of a company and ran it like God runs the universe, I’d be fired.”

— Wine interview, The Guardian (Sept. 18, 2007)

Patton Oswalt

On this date in 1969, Patton Oswalt was born in Portsmouth, Va. His father was a Marine Corps officer who named him after Gen. George S. Patton. Oswalt began to perform stand-up comedy in the late 1980s, before graduating from the College of William and Mary in 1991. He became widely known after he starred in an HBO comedy special in 1996. He began to headline at comedy clubs nationwide and also started his career as an actor.

Much of his comedic material addresses popular culture and his daily life, but he has been known to mock religion and religious believers. For example, his “Sky Cake” routine characterizes religion as a trick played by smart weak guys on big dumb guys. He describes himself as an atheist.

From 1998 to 2007, Oswalt was a regular on the CBS show “The King of Queens,” playing the role of Spence. He has appeared in many small roles in movies, as a guest star on television shows including “Dollhouse” and “Nurse Jackie,” and done voice work for movies, television and video games. Notably, he voiced the main character, the rat Remy, in the 2007 Pixar film “Ratatouille.” He also starred in the 2009 live-action film “Big Fan.”

His supporting role in Jason Reitman’s black comedy “Young Adult” (2011) was nominated for several awards. Oswalt has also written for TV and film, as well as doing uncredited work on a variety of live-action comedy and animated film scripts.

In 2011 Oswalt released the book Zombie Spaceship Wasteland and appeared in “A Very Harold & Kumar 3D Christmas.” He originated the role of Billy Stanhope on “Two and a Half Men.” His memoir Silver Screen Fiend: Learning About Life from an Addiction to Film was published by Simon & Schuster in 2015, when it was announced he would appear in the reboot of “Mystery Science Theater 3000.” His comedy special “Talking for Clapping” was released on Netflix in 2016 and his special “Annihilation” followed in 2017 on Netflix.

Oswalt married true-crime writer Michelle McNamara in 2005 and they had a daughter, Alice, in 2009. McNamara had a very sad, untimely end at age 46 in 2016. He married actress Meredith Salenger the following year.

“My feelings on religion are starting to morph. I’m still very much an atheist, except that I don’t necessarily see religion as being a bad thing. … I’m almost saying certain people do better with religion, the way that certain rock stars do better if they’re shooting heroin.”

— Oswalt, The Onion A.V. Club (Aug. 31, 2011)

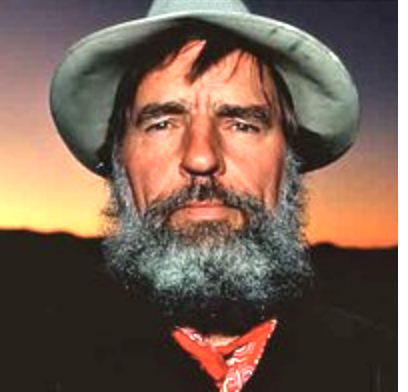

Edward Paul Abbey

On this date in 1927, author Edward Paul Abbey was born in Indiana, Pa., to Mildred (Postlewait) and Paul Abbey, the eldest of five siblings. Both were hardworking, independent persons, and while Mildred was a lifelong liberal Presbyterian, Paul was more radical, declaring himself an atheist and a socialist as a young adult. Edward Abbey served in the U.S. Army as a military police officer in Italy and then enrolled at the University of New Mexico, where he earned a B.A. in philosophy and English in 1951 and a master’s in philosophy in 1956. He married Jean Schmechal, the first of his five wives (with whom he had five children), as an undergrad. He was removed as editor of the student newspaper for putting Diderot’s famous quote, “Man will never be free until the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest,” on the cover of one issue.

He worked as a welfare caseworker, teacher, bus driver and technical writer before starting a career as a ranger and fire lookout at several national parks or monuments. His two seasons at Arches National Monument (later a national park) near Moab, Utah, in 1956-57 provided the grist for the book that brought him acclaim, Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness (in 1968), a nonfiction work that was preceded by three novels. His 1975 comic novel The Monkey Wrench Gang, about a group of ecological saboteurs is perhaps his best-known work. While he wrote primarily about environmental issues and land-use policies, Abbey was basically a political anarchist, and according to Wilderness.net, “he wasn’t comfortable with environmental activists or activism as a whole.”

His best friend Jack Loeffler recorded Abbey’s thoughts on religion after their 1983 camping trip in the Superstition Mountains of Arizona, included in his 1989 book Headed Upstream: Conversations with Iconoclasts, in which Abbey said, “I regard the invention of monotheism and the otherworldly God as a great setback for human life.” Abbey himself roundly condemned religion in his own works, particularly in A Voice Crying in the Wilderness, published in 1989, the year he died of esophageal hemorrhaging after surgery for a congenital circulatory disorder. “What is the difference between the Lone Ranger and God?” Abbey asked, before answering, “There really is a Lone Ranger.”

“Whatever we cannot easily understand we call God; this saves much wear and tear on the brain tissues.”

— "A Voice Crying in the Wilderness: Notes from a Secret Journal" (1989)

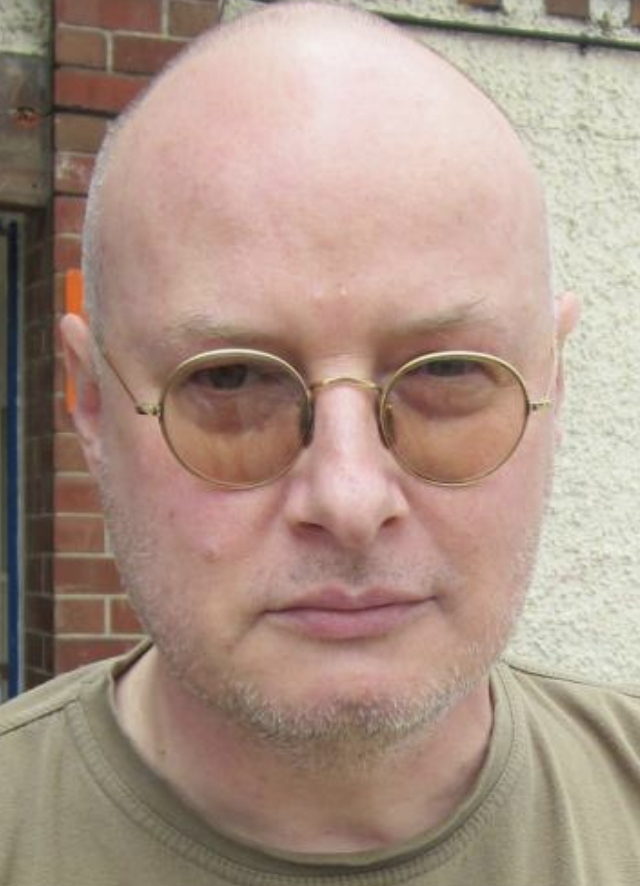

Barry Duke

On this date in 1947, journalist/editor and gay rights activist Barry Duke was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, the eldest child of middle-class parents Sybil and Abe Duke. He grew up in two small towns, and from an early age showed “a strong antipathy toward religion, especially the Calvinist form of Christianity that was used to justify the country’s horrific persecution of people of color during the Apartheid era,” Duke commented in 2022.

He was expelled from the first high school he attended for condemning racial injustices, refusing to sing the national anthem and for sharing anti-religious publications with classmates. He started working as a newspaper journalist in his late teens and several years later landed a job with The Star, a leading daily.

Duke’s left-leaning, anti-Apartheid activism, coupled with censorship battles, led to him being declared a “dangerous undesirable.” Alerted that an arrest warrant was being issued, he left South Africa in 1973 for the UK, where he was granted asylum. A militant atheist, he joined the National Secular Society and was a co-founder in 1979 of the Gay Humanist Group, which changed its name to the Gay and Lesbian Humanist Association in 1987.

He started writing in 1974 for The Freethinker, the venerable publication founded by G.W. Foote in 1881, and rose to editor in 1997. He held the position until January 2022, when differences with the editorial board led to his departure. He continued his decade-long writing and editing association with the Pink Humanist and started writing on OnlySky, a secular platform that launched in 2020.

In 2017 Duke was the recipient of a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Secular Society for his “spirited opposition to religious intolerance and irrationality.” He married Marcus Robinson, his longtime partner, in 2017 in Gibraltar and they live in Benidorm, a town along Spain’s seaside Costa Blanca.

“Since [1950s John Birch Society claims], War on Christmas reports have simply become a silly festive season tradition, generating more mirth than fury. All are intended to reinforce the belief of Christian fundamentalists that they really are being persecuted by a coalition of atheists, secularists, freethinkers, abortionists – and those who identify as LGBTQ. Seriously!”

— "And so it begins … the ‘war’ on Christmas 2021" (The Freethinker, Nov. 25, 2021)

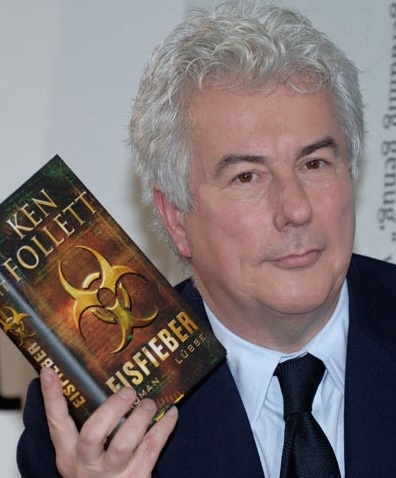

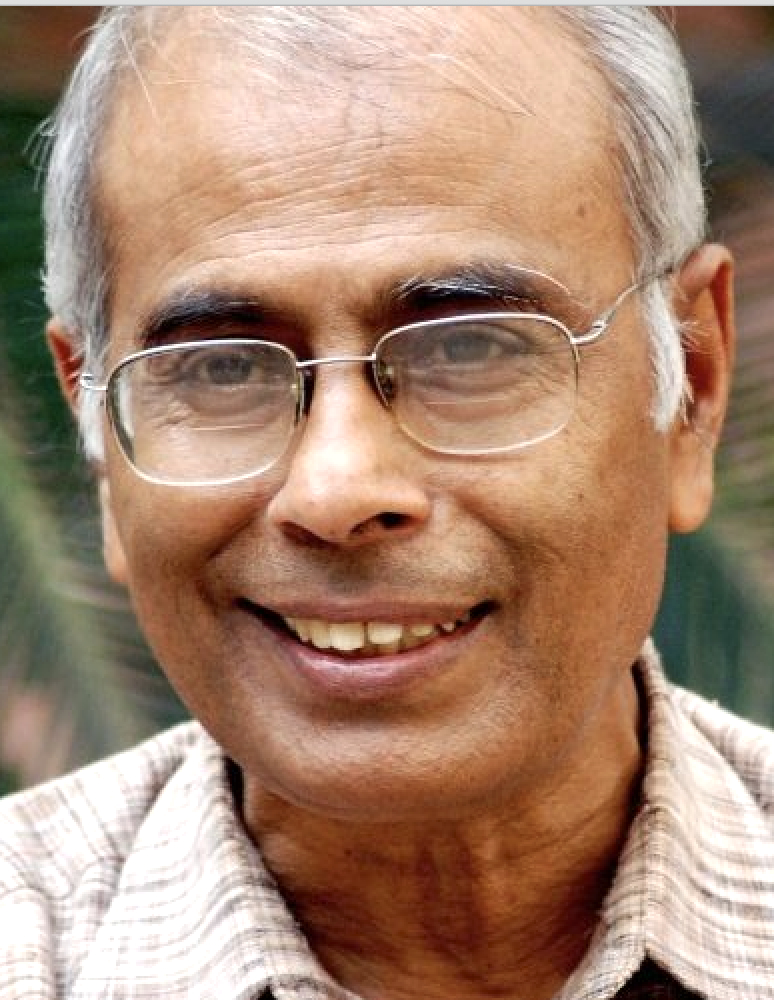

Michael Martin

On this date in 1932, renowned American philosopher and teacher Michael Martin was born in Cincinnati, Ohio. Martin was a respected academic promoter of atheism, penning several books examining the case against the existence of God.

Martin served with the U.S. Marine Corps in the Korean War before graduating from Arizona State University in 1956 with a degree in business administration. He earned a master’s degree in philosophy in 1958 from the University of Arizona and a Ph.D. in philosophy from Harvard University in 1962. That year, Martin began his teaching career at the University of Colorado as an assistant professor, joining the staff at Boston University in 1965, where he was a professor of philosophy until retiring.

The focal point of Martin’s research and writing was always the philosophy of religion and the defense of atheism. His best-known book was Atheism: A Philosophical Justification (1989), considered by some as one of the most analytical arguments against God’s existence. In its introduction he writes, “The aim of this book is not to make atheism a popular belief or even to overcome its invisibility. My object is not utopian. It is merely to provide good reasons for being an atheist. … My object is to show that atheism is a rational position and that belief in God is not. I am quite aware that atheistic beliefs are not always based on reason. My claim is that they should be.”

Martin wrote and edited several other books, including The Case Against Christianity (1991), Atheism, Morality, and Meaning (2002), The Impossibility of God (2003), The Improbability of God (2006) and The Cambridge Companion to Atheism (2006), along with numerous articles on atheism. He also engaged in a number of debates with Christian apologists. His philosophical interests extended to social science and law.

Martin was married to Jane Roland Martin, who spent much of her career as a philosophy professor at the University of Massachusetts-Boston focusing on education, gender and feminism. They married in 1962 and had two sons, Timothy and Thomas, and five grandchildren. (D. 2015)

“Since experiences of God are good grounds for the existence of God, are not experiences of the absence of God good grounds for the nonexistence of God?”

— Michael Martin, "Atheism: A Philosophical Justification" (1989)

Sikivu Hutchinson

On this date in 1969, Black activist, author and feminist Sikivu Hutchinson was born in Los Angeles to Yvonne (Divans) and Earl Ofari Hutchinson Jr., respectively a retired English teacher and a noted analyst and commentator on race, politics and civil rights. Her grandfather, Earl Hutchinson Sr., published his autobiography A Colored Man’s Journey Through 20th Century Segregated America when he was 96.

Hutchinson earned a B.A. in anthropology from UCLA and a Ph.D. in performance studies from New York University in 1999. She taught women’s studies, cultural studies, urban studies and education at UCLA, the California Institute of the Arts and Western Washington University.

Her first book was Imagining Transit: Race, Gender, and Transportation Politics in Los Angeles (2003) and was followed by Moral Combat: Black Atheists, Gender Politics, and the Values Wars (2011), Godless Americana: Race and Religious Rebels (2013) and Humanists in the Hood: Unapologetically Black, Feminist, and Heretical (2020).

Her novel White Nights, Black Paradise (2015), with a focus on Black women, the Peoples Temple and the Jonestown massacre, was later adapted for the stage. Her novel Rock ’n’ Roll Heretic: The Life and Times of Rory Tharpe (2021) detailed the life of an ex-Pentecostal Black female electric guitarist who at one point says, “Those white boys on the major labels would never give an inch to a Negro woman playing race music.”

Hutchinson founded Black Skeptics Los Angeles (BSLA) in 2010 and is the founder of the Women’s Leadership Project, a high school feminists of color mentoring program in South Los Angeles. She received the Foundation Beyond Belief’s 2015 Humanist Innovator award and the Secular Student Alliance’s 2016 Backbone award. In 2020, the Humanist Chaplaincy at Harvard, a chapter of the American Humanist Association, named her one of its three Humanists of the Year.

BSLA has twice partnered with the Freedom From Religion Foundation by selecting recipients for FFRF’s Forward Freethought Tuition Relief Scholarships. In 2020, four secular students of color each received $5,000 stipends, double the amount of the inaugural awards.

Hutchinson has written and spoken extensively on the particular challenges of “coming out” as an atheist female of color. “[P]atriarchy entitles men to reject organized religion with few implications for their gender-defined roles as family breadwinners or purveyors of cultural values to children. Men simply have greater cultural license to come out as atheists or agnostics.” (Feminism: Opposing Viewpoints, April 1, 2012)

She has been married to Stephen Kelley as of this writing in 2023 for 17 years and has a nonbinary daughter, Jasmine Hutchinson Kelley. She’s a distance runner, acoustic guitarist and rock music enthusiast whose favorites include the Beatles, Neil Young, Sonic Youth, Parliament/Funkadelic, Hendrix/Band of Gypsys, Malina Moye, Brittany Howard, David Bowie and Bob Dylan.

“The white fundamentalist Christian stranglehold on Southern and Midwestern legislatures has proven to be a national cancer that further exposes the dangerous lie of a God-based, biblical morality.”

— Hutchinson, commenting on restrictive abortion bills, The Humanist magazine (July/August 2019)

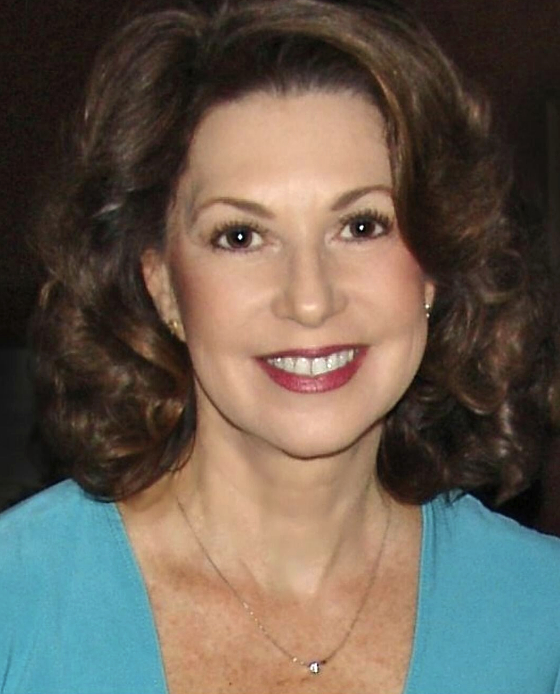

Pamela Paul

On this date in 1971, journalist and author Pamela Lindsey Paul was born in New York to Carole and Jerome Paul. Her father was a construction contractor and her mother was an advertising copywriter and, later, editor of Retail Ad World. She has 7 brothers. Her parents divorced when she was 3 or 4.

“Like many other morbid kids with Jewish ancestry, I was drawn to Holocaust reading from the moment I entered adolescence, seeking out the death and torture and deprivation and evil,” Paul said in her 2017 memoir “My Life With Bob.” Bob (short for Book of Books) was her journal detailing all the books she had read since high school and her intense relationship with reading. She lived with her mother on Long Island except for weekends with her father on New York’s Upper West Side.

She enrolled at Brown University in Providence, R.I. As a challenge to herself, she joined the rugby team. “And I joined a gospel choir even though I’m an atheist and I can’t sing. I guess I do have a streak of wanting to put myself in situations that are uncomfortable and challenging and like, can you take it?” (Women’s Wear Daily, April 20, 2021)

After graduation, Paul taught American history at a startup international school in Thailand before taking marketing jobs at Scholastic Inc. and Time Inc. in New York. She then joined fiancé Bret Stephens in London, where she first wrote professionally with a monthly column on global arts in The Economist.

Her reporting and columns have appeared in numerous notable publications. Her first book, “The Starter Marriage and the Future of Matrimony” (2002), came in the wake of her divorce from conservative journalist Bret Stephens, whom she wed in 1998. A starter marriage was defined as starting before age 30, being childless and ending within five years.

She joined The New York Times in 2011 as a columnist, children’s books editor and features editor. She edited the paper’s Book Review for nine years before becoming an opinion columnist, a position she maintained until leaving the paper in April 2025. She has written eight books, the most recent being “Rectangle Time” and “100 Things We’ve Lost to the Internet,” both published in 2021.

Paul came under fire in 2023 for defending author J.K. Rowling from allegations of transphobia, “because she has asserted the right to spaces for biological women only, such as domestic abuse shelters and sex-segregated prisons” and for insisting “that when it comes to determining a person’s legal gender status, self-declared gender identity is insufficient.” (The Advocate, Feb. 16, 2023) Rowling also received substantial support from groups traditionally seen as backing women’s and LGBTQ+ rights.

Amy Schneider, the first trans contestant on “Jeopardy!” and the highest-winning woman in the show’s history, was a critic: “If certain famous billionaire authors were to advocate for ‘Whites only’ spaces, we’d all see it as the hate speech that it is. But when they advocate for ‘cis only’ spaces, the most powerful newspaper in the country rushes to their defense.” (Schneider tweet, Feb. 16, 2023)

In a column headlined “I Pledge Allegiance to … My Conscience” (March 16, 2023), Paul praised Marissa Barnwell, 15, a Black honor student grabbed by a South Carolina teacher and shoved against a hall wall for not acknowledging that the Pledge of Allegiance was being recited over a loudspeaker. She’d stopped saying the pledge in third grade. “Don’t you love this country?” the teacher asked.

Something similar happened to Paul in the second grade when she opted out of the pledge, despite being “painfully shy,” and was sent to the principal’s office. “I remember my mother being called and that whatever she said must have appeased them.” The Barnwells are suing the school district for violating the First and Fourteenth amendments.

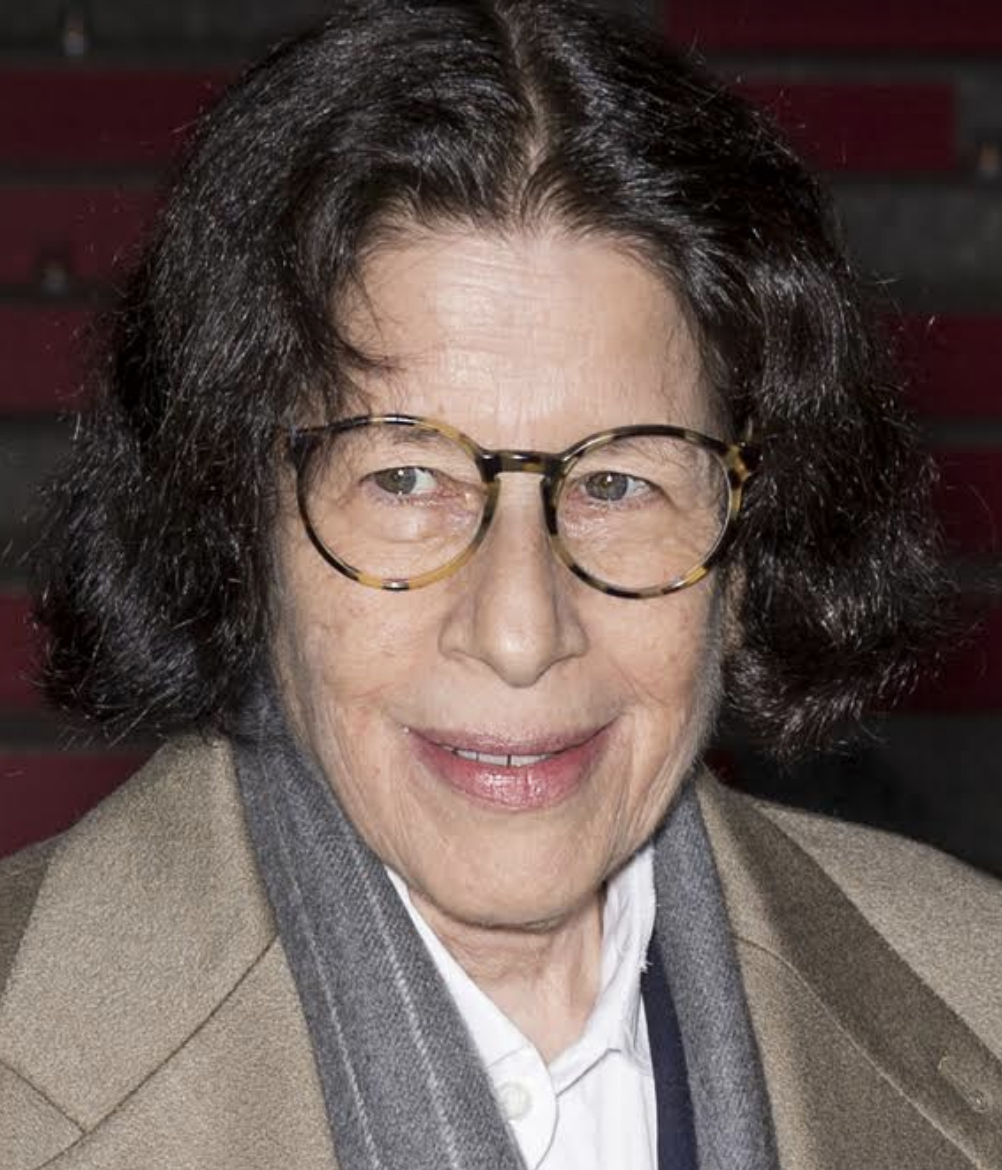

PHOTO: Paul at the 2019 Texas Book Festival in Austin; photo by Larry D. Moore, CC BY-SA 4.0.

“Unhappy with what much of the country believes, the court’s right wing chooses to believe what it would like and foists the results on the rest of us. Just like Coach Kennedy, they’re out to proselytize.”

— Paul slamming the SCOTUS 6-3 decision in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District that held a public high school football coach's onfield prayer was constitutional. (New York Times, July 17, 2022)

Matt Taibbi

On this date in 1970, muckracking atheist journalist Matthew C. “Matt” Taibbi was born in New Brunswick, N.J. The son of an NBC reporter, he grew up in Boston and graduated from Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y. He moved to Russia in 1992 and studied and worked there and in Uzbekistan and Mongolia for over six years. In 1997 he co-edited with Mark Ames an English language newspaper called the eXile, geared to expatriates in Moscow. It provided background for his first book, with Ames and Edward Limonov, The Exile: Sex, Drugs, and Libel in the New Russia (2000).

He then started The Beast, a satirical biweekly in Buffalo, N.Y., but left to concentrate on freelancing for The Nation, Playboy, Rolling Stone and New York Press (which he left in 2005 after his editor Jeff Koyen was fired over issues raised by Taibbi’s column “The 52 Funniest Things About the Upcoming Death of the Pope”). Taibbi defended the piece as “off-the-cuff burlesque of truly tasteless jokes” to relieve readers of his “fulminating political essays.” He covered the 2008 presidential campaign for “Real Time with Bill Maher.”

He received a 2008 National Magazine Award in the category “Columns and Commentary” for his Rolling Stone columns. His article “The Great American Bubble Machine,” which detailed Goldman Sachs’ involvement in the financial meltdown, received a 2009 Sidney Award from the Sidney Hillman Foundation. His 2008 book The Great Derangement: A Terrifying True Story of War, Politics, and Religion told the story of how he infiltrated Texas evangelical pastor John Hagee’s Cornerstone megachurch and school and Hagee’s “near-absolute conquest of a very trendy niche in the market: Christian Zionism.”

He has also written Griftopia: Bubble Machines, Vampire Squids, and the Long Con That Is Breaking America (2010), The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap (2014), Insane Clown President: Dispatches from the 2016 Circus (2017) and Hate Inc.: Why Today’s Media Makes Us Despise One Another (2019). He and his wife Jeanne, a family physician, were married in 2010 and live in New Jersey with their son.

MEHTA: What role should religion play in the political arena?

TAIBBI: Well, I’m an atheist/agnostic, so I would say none. People should stick to solving the problems they have the tools to solve. If you have a budget crisis, well, human beings can do the math, work out a new tax/spending strategy, and fix that. But we don’t have any tools for [divining] the will of God as it relates to, say, a new problem like high school shootings, the Iraq war, or the AIDS virus. All we have are the opinions of religious leaders whose motives may or may not be pure, and whose grasp of logic may or may not be of the highest quality. If you inject religion into the equation, the debate is necessarily going to be subjective, emotional, and inconclusive. It’s also very easy for unscrupulous people to use religion to further various ends for other reasons. Hagee’s humping of Israel is a great example. How do you get fundamentalist Christians to support the financial subsidy of military aid to a Jewish state? Easy; you convince them the world is going to end soon, and that we’re going to be on the wrong side of Armageddon unless we support Israel.”— Interview with "Friendly Atheist" Hemant Mehta (April 29, 2008)

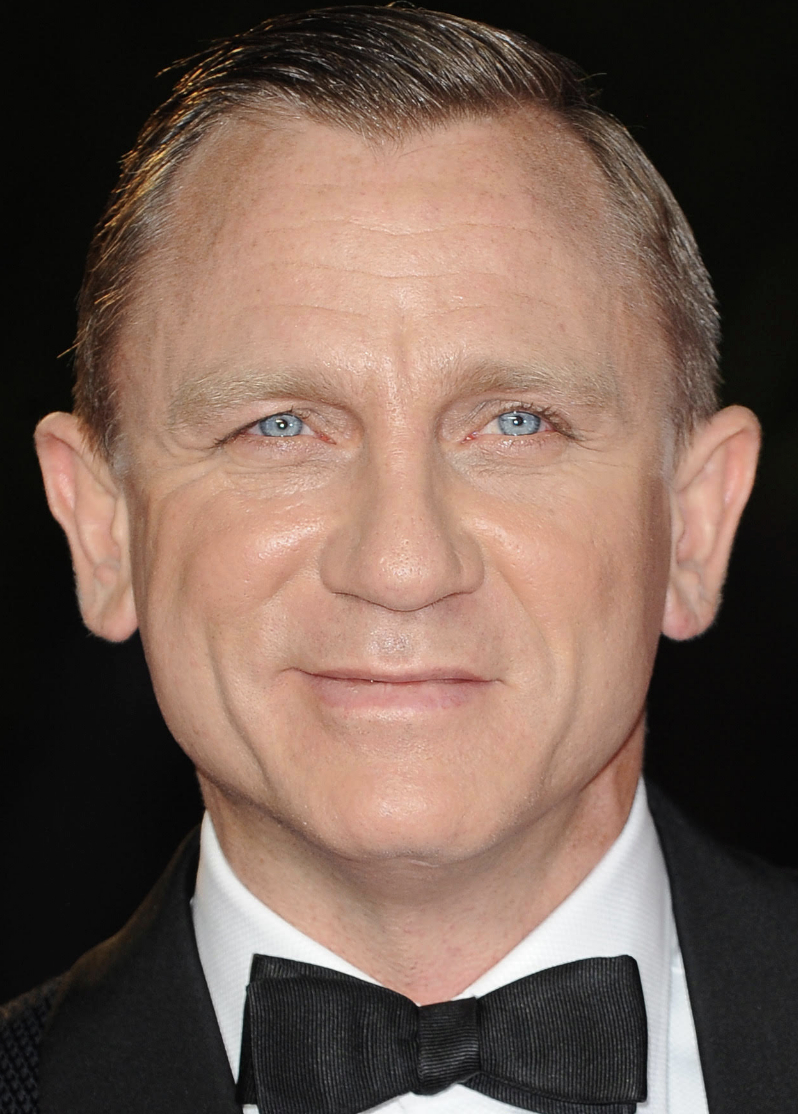

Daniel Craig

On this date in 1968, actor Daniel Wroughton Craig was born in Chester, England to Carol (née Williams) and Timothy Craig, respectively an art teacher and midshipman in the merchant marine. He began acting in school plays at age 6. At 16 he was accepted into the National Youth Theatre and then by the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, graduating in 1991.

Craig made his film debut in the drama “The Power of One” (1992) and appeared the next year in the Royal National Theatre’s production of “Angels in America” by playwright Tony Kushner. Throughout the 1990s, he played a variety of roles in screen and television productions. He co-starred with Angelina Jolie in the 2001 action film “Lara Croft: Tomb Raider” and achieved international fame in 2006 when he played James Bond, taking over from Pierce Brosnan, in “Casino Royale.”

It earned him a nomination for the BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role. He followed with the sequels “Quantum of Solace” (2008), “Skyfall” (2012), “Spectre” (2015) and “No Time to Die,” which was scheduled for release in April 2020 but was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It was released in 2021. Craig’s role in the 2019 mystery film “Knives Out” earned him a Golden Globe nomination for Best Actor.

He married actress Fiona Loudon in 1992. They had a daughter, Ella, before divorcing in 1994. After long-term relationships with actress Heike Makatsch and film producer Satsuki Mitchell, he married actress Rachel Weisz in 2011. They announced the birth of a daughter in 2018.

Craig is notoriously private about his personal life and beliefs, although he has said he’s an atheist (see quote below). In 2019 in a Kaufmann Store interview, he said, “I don’t go to church. I’m not religious. But I think religion is fascinating because it affects our lives massively.”

When he hosted “SNL” on March 7, 2020, a sketch he appeared in with Kate McKinnon and Cecily Strong brought laughs from the audience. McKinnon: “Blace, I thought you left to become a priest.” Craig answered: “Yes, but I couldn’t do it — the no-sex part. Also, have you read the bible? It’s weird.”

PHOTO: Craig at the 2012 premiere of “Skyfall” at the Royal Albert Hall, Kensington, UK; photo via Shutterstock by Landmarkmedia.

DIE ZEIT: Are you a believer?

CRAIG: I’m an atheist.— Craig, quoted in the German weekly Die Zeit, "Real Heroes Are Shy" (Jan. 12, 2012)

Maurice Ravel

On this date in 1875, Joseph Maurice Ravel, composer, pianist and conductor, was born in the Basque town of Ciboure, France. His father, Pierre-Joseph Ravel, was an educated engineer, inventor and manufacturer. His mother, Marie (née Delouart) Ravel, was born to an unwed mother and was barely literate. She was also a freethinker, a trait inherited by Maurice, who was always politically and socially progressive as an adult, according to musicologist and Ravel scholar Arbie Orenstein.

He was admitted to France’s premier music academy, the Conservatoire de Paris, winning first prize in the school’s piano competition in 1891. He was expelled in 1895 due to differences with faculty conservatives but was readmitted two years later and studied composition with Gabriel Fauré. He was later forced out again after clashing with Conservatoire Director Théodore Dubois, who deplored Ravel’s musical and political progressivism.

Making his way as an orchestral arranger and composer, he was often associated with his contemporary Claude Debussy as an impressionist, though neither liked the term. He liked to experiment with musical form, as is evident in “Boléro” (1928), his best-known work. “Boléro” is a one-movement orchestral piece originally composed as a ballet that repeats its main melody 18 times by solo or combinations of instruments. The duration varies depending on the tempo but typically is about 16 minutes. When Toscanini conducted it faster, Ravel objected, resulting in hard feelings. “When I play it at your tempo, it is not effective,” Toscanini said. To which Ravel supposedly replied, “Then do not play it.”

Ravel, a master of orchestration, worked at a slower pace than many of his contemporaries. Among his 85 works, many incomplete, are pieces for piano, chamber music, two piano concertos, ballet music, two operas and eight song cycles. He wrote no symphonies or church music. He was among the first to realize the potential of recording music. According to a 1914 article in the French magazine Comoedia illustré, there’s “a notable absence of religious forms or references” in his works. “His habitual inspiration came from nature, from fairy tales and folk songs, and from classical and Oriental legends. Nor was he always sympathetic to the religious works of other composers.”

Although he never married and was childless, Ravel liked children and wrote piano music they could play and reflected their world. He wrote “Ma Mère l’Oye” (Mother Goose), subtitled “cinq pièces enfantines” in 1910 as a duet and dedicated it to his students, Mimie Godebska and her brother Jean. “It was he who made me read the Fioretti (Little Flowers) of St. Francis of Assisi. Although he was a confirmed atheist, he adored this book, and I was so amazed by it that I used to imagine it being set to music — by Ravel,” wrote Mimie Godebska Blacque-Belair in 1938.

Ravel started to suffer from neurological impairment in the early 1930s, which affected his piano playing, touring and conducting. The cause was never determined but may have been dementia, Alzheimer’s or Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. He died at age 62 and was buried next to his parents with no religious ceremony. (D. 1937)

PHOTO: Ravel at age 50.

“What you write to me about the benefits of religion, we have spoken of it with Pierrette Haour, an atheist like me.”

— Ravel letter in 1920 to Ida Godebska, cited in "Maurice Ravel: lettres, écrits, entretiens" (letters, writings, interviews), Arbie Orenstein, ed., (1989)

Ed Buckner

On this date in 1946, educational researcher, author and religious skeptic Edward Milton Buckner was born in Fitzgerald, Ga. His father was an Episcopal clergyman. (One of his congregants when the family lived in Texas was astronaut Frank Borman.) Buckner, who said he started “gradually coming to my senses as an atheist” in the 1960s, received a B.A. from Rice University in Houston in 1967 and an M. Ed. and Ph.D. from Georgia State University. He married Diane Bright in 1968 and their son Michael was born in 1970. They are Life Members of the Freedom From Religion Foundation.

Buckner was an assistant professor of urban studies at Georgia State University from 1980 to 1986. He taught research methods, statistics and computer use and was responsible for managing and conducting data analysis from research projects. He then worked as a researcher for a public school system and later served as executive director of the Council for Secular Humanism (2001-03), as president of American Atheists (2008-10) and as American Atheists interim executive director for several months in 2018.

An example of Buckner’s ability to be a burr under the saddle of government favoritism to religion was noted in November 2007 by USA Today. He and about 20 others protested “a revival-style vigil” outside the state Capitol, where Gov. Sonny Perdue prayed with hundreds of Georgians for rain to ease a severe drought as “Amazing Grace” played: “We ask God to shower our state, our region, our nation with the blessings of water.” Buckner told the newspaper: “I am embarrassed that my governor thinks ordinary Georgians praying is not enough, that we need to have a mixing of church and state to get the attention of the Almighty.”

Two years later, he addressed the Cobb County Commission with a “prayer” of his own: “[T]hese invocations are a violation of the letter and intent of the Constitution of the state of Georgia, of the 1st Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and of the 14th Amendment, ratified exactly 141 years ago today. Go and sin no more. Thank you.”

Buckner has edited Freethought Press books and with Michael co-edited Quotations That Support the Separation of Church and State (1995). Father and son co-wrote In Freedom We Trust: An Atheist Guide to Religious Liberty, published by Prometheus Books in 2012. Along with writing and editing, Buckner has debated and spoken in the U.S. and U.K. about freethought and secular humanism. What does he think about the Bible? “A dangerous set of books, full of beauty, moral wisdom and history, but mixed with viciousness, cruelty, myth and immorality.” (2010 interview with tabee3i, an online home for Metaphysical Naturalists “rejecting the existence of the supernatural”)

PHOTO: By Diane Buckner

“The stigma attached to being an atheist based on atheists being hopelessly immoral, outrageously in rebellion against a loving God, and in league with Satan (possibly as foolish dupes rather than his evil minions) was pervasive. The stigma has not ended, the fear of and hatred of us has not abated, the ignorance and misunderstanding is still widespread.”

— Ed Buckner, "A Look Back From an Old Guy Not in the Old Guard" (American Atheist magazine, Second Quarter 2013)

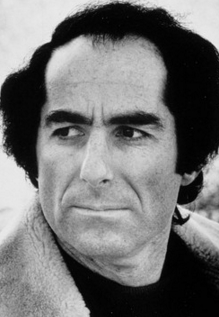

Philip Roth

On this date in 1933, author Philip Milton Roth was born to Herman Roth and Bess (Finkel) Roth in Newark, N.J., where he grew up with an older brother. He encountered anti-Semitism at an early age and later wrote that his childhood love of baseball offered him “membership in a great secular nationalistic church from which nobody had ever seemed to suggest that Jews should be excluded.” At Bucknell University he decided the school’s “respectable Christian atmosphere [was] hardly less constraining than [his] own particular Jewish upbringing.”

After earning a master’s in English in 1955 from the University of Chicago, he taught there for two years and started writing short fiction. Roth published Goodbye, Columbus, a collection of short stories and the title novella, to critical acclaim in 1959. He then worked as a visiting lecturer at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, followed by two years as a writer-in-residence at Princeton University. Letting Go (1962) was his first full-length novel. When She Was Good (1967), which Roth once called a “book with no Jews,” is also his only novel to feature a female protagonist.

He had married Margaret Martinson in 1956. They separated in 1963 and she died in a car accident in 1968. Martinson was the inspiration for female characters in several of his novels, including Lucy Nelson in When She Was Good. He didn’t marry again until 1990, when he wed English actress Claire Bloom. They divorced in 1995, after which she published a memoir that described their marriage in detail unflattering to Roth. Both marriages were childless.

Roth started teaching literature in the late 1960s at the University of Pennsylvania. The 1969 feature film adaptation of Goodbye, Columbus coincided with the publication of Portnoy’s Complaint, which soon became a best-seller amid controversy for its prurient content. (Those who’ve read it will likely not forget Portnoy’s “affair” with a slab of liver.) Roth’s works in the 1970s included a Richard Nixon parody titled Our Gang, The Breast, The Great American Novel and, what some consider his best novel, My Life as a Man. Three novels (The Ghost Writer, Zuckerman Unbound and The Anatomy Lesson) were published in one volume in 1985.

The 1990s saw publication of Deception, Patrimony: A True Story, Operation Shylock, Sabbath’s Theater and a trilogy consisting of American Pastoral (which won a Pulitzer), I Married a Communist and The Human Stain. He remained prolific after the turn of the century with The Dying Animal, The Plot Against America, Everyman, Indignation, The Humbling, Nemesis and Exit Ghost, the ninth book narrated by Zuckerman, Roth’s fictional alter ego.

Roth won a slew of writing awards besides the Pulitzer and eight of his novels were adapted for movies. He was awarded the 2010 National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama at the White House in 2011. He died of congestive heart failure at age 85. (D. 2018)

PHOTO: Roth in 1973.

“I’m exactly the opposite of religious, I’m anti-religious. I find religious people hideous. I hate the religious lies. It’s all a big lie. … I have such a huge dislike. It’s not a neurotic thing, but the miserable record of religion. I don’t even want to talk about it, it’s not interesting to talk about the sheep referred to as believers.”

“Do you consider yourself a religious person?”

“No, I don’t have a religious bone in my body,” Roth said.

“So, do you feel like there’s a God out there?” Braver asked.

“I’m afraid there isn’t, no,” Roth said.

“You know that telling the whole world that you don’t believe in God is going to, you know, have people say, ‘Oh my goodness, you know, that’s a terrible thing for him to say,” Braver said.

Roth replied, “When the whole world doesn’t believe in God, it’ll be a great place.”— Interview with Martin Krasnik of The Guardian (Dec. 14, 2005); interview with CBS News correspondent Rita Braver (Oct. 3, 2010)

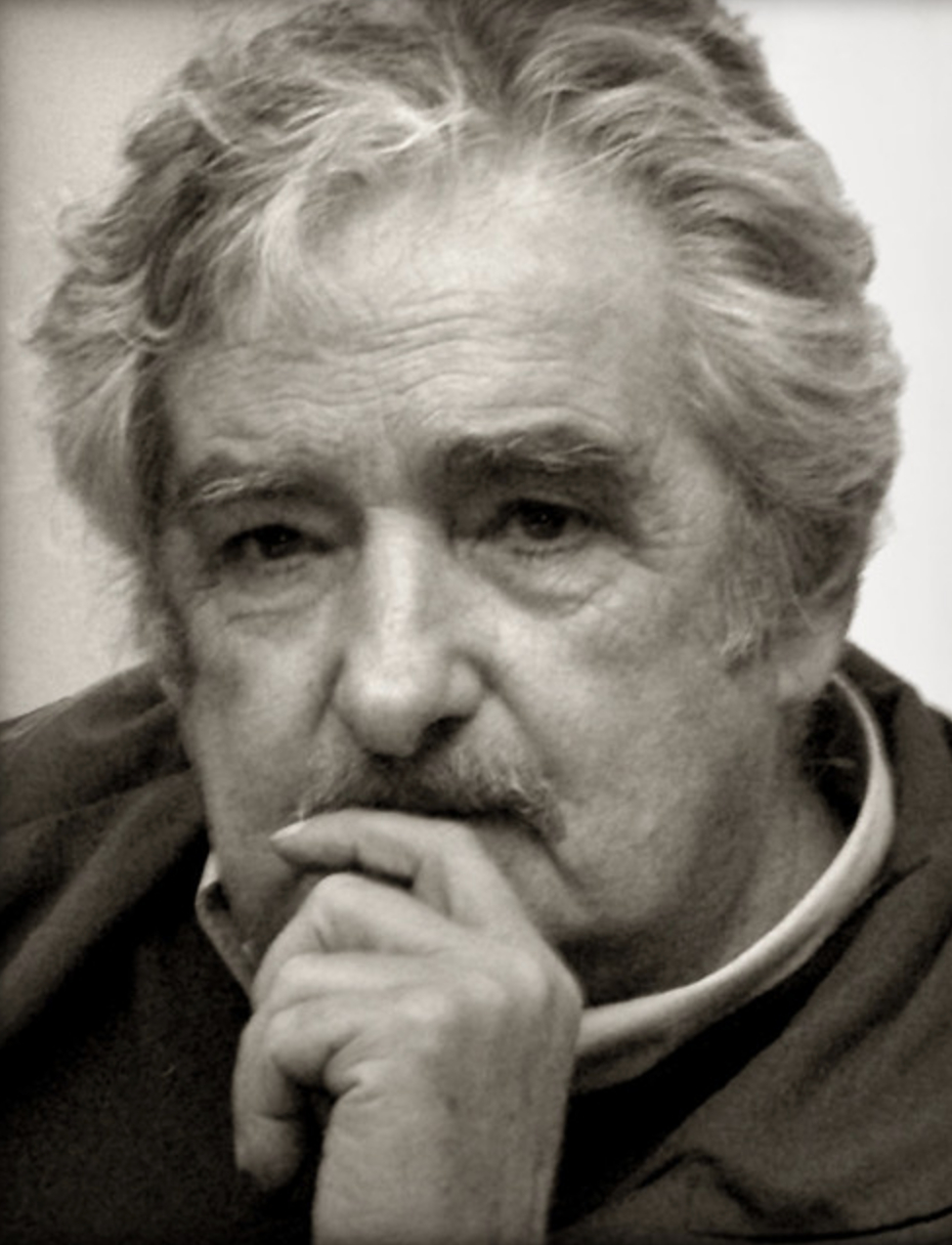

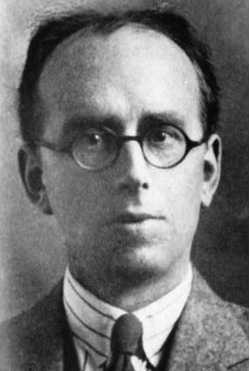

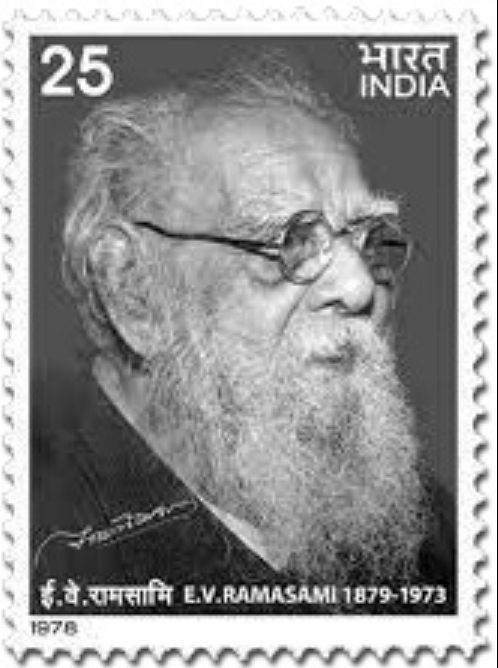

Béla Bartók

On this date in 1881, composer, pianist and ethnomusicologist Béla Bartók was born in Nagyszentmiklós, Hungary. He and Franz Liszt are regarded by many as the greatest Hungarian composers. Trained in piano and composition at the Budapest Academy of Music, Bartók began his career as a touring pianist in 1903. His talents as a composer soon became apparent, and Bartók assumed a professorship at the academy in 1908.

He drew inspiration from the folk music of the Balkans and other regions while engaging in intense studies of harmonic practices, including those of contemporary French composers. While not an expert in stringed instruments, Bartók’s compositions displayed a preternatural understanding of the violin: “He enriched [the violin’s] repertoire with such essential works as his two Sonatas for Violin and Piano (of 1921 and 1922, respectively), two Rhapsodies for Violin and Orchestra (1928-29), 44 Duos for Two Violins (1931), and the Sonata for Solo Violin (1944).” (New York Philharmonic)

His childhood Catholicism was gone by early adulthood. “By the time I had completed my 22nd year, I was a new man — an atheist.” (Béla Bartók: Life and Work by Benjamin Suchoff, 2001) He later became attracted to Unitarianism and publicly converted in 1916. A committed anti-fascist, Bartók opposed Hungary’s alliance with Germany in World War II and refused to perform in Germany during Nazi rule.

He married Márta Ziegler in 1909 when he was 28 and she was 16. They divorced in 1923 and he married Ditta Pásztory, a piano student, two months later when she was 19 and he was 42. He had two sons, Béla Bartók III and Péter. Bartók and Ditta emigrated to the U.S. in 1940 and he accepted a research fellowship at Columbia University, where they compiled a large collection of Serbian and Croatian folk songs for Columbia’s libraries. He died at age 64 in New York from complications of leukemia. (D. 1945)

PHOTO: Bartók’s portrait on a 1,000-forint banknote. Hungarian National Bank photo. GNU Free Documentation License

“To violinist Stefi Geyer, he once wrote about his religious belief, calling the trinity a ‘clumsy fable’ that ‘enslaves thought.’ … The existence of the universe did not require the hypothesis of a creator. ‘Why don’t we simply say: I can’t explain the origin of its existence and leave it at that?’ “

— "Béla Bartók" by David Cooper (2015)

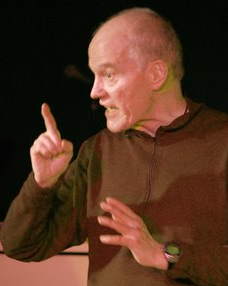

Matt Dillahunty

On this date in 1969, public speaker and internet personality Matthew Wade Dillahunty was born in Kansas City, Mo. He was raised in a Southern Baptist home. He was a fundamentalist Christian for over 20 years, but after serving from 1987-95 in the U.S. Navy and working in high tech, he found a need to reaffirm his faith in order to continue a life with the ministry. This attempt to fortify his faith turned into a long-term investigation to understand reason in terms of his religion.

From 2006-13, Dillahunty was president of the Atheist Community of Austin, Texas. The ACA is a nonprofit organization with a variety of goals including developing and supporting the atheist community, providing opportunities for socialization and friendship and working with like-minded organizations to oppose discrimination against atheists. Not only does the ACA serve its local community, it provides an online portal of free resources accessible to the community at large.

One of its most-effective outreach projects is “The Atheist Experience” TV show, a weekly program geared towards a nonatheist audience. Dillahunty has been hosting the show since 2005 and was a co-host of “The Non Prophets” internet radio show prior to that.

He also founded The Iron Chariots, an online encyclopedia intended to provide information on philosophical apologetics and non-apologetics. Additionally, he contributed to the novel Deconverted: a Journey from Religion to Reason (2012), an autobiographical account of a Protestant Christian who eventually creates a popular online atheist community called The Thinking Atheist. Dillahunty travels nationwide as a member of the Secular Student Alliance’s speaker’s Bureau. In 2012, he won the Catherine Fahringer Freethinker of the Year Award from the Freethinkers Association of Central Texas.

In Episode 771 of “The Atheist Experience” (July 22, 2012), Dillahunty called the Catholic Church “a nonsensical organization; a bunch of fat lazy do-nothings who have been living off the public dole for centuries. The fact that they can do good is a testament to the fact that there are good people who will do good. But the organization is corrupt, it is poison to its core and it serves no essential good purpose – no true purpose. It’s lie after lie, promoting harm to real people …”

In 2011 he married Beth Presswood, an “Atheist Experience” colleague and co-host of “The Godless Bitches” podcast. They divorced in 2018.

PHOTO: Dillahunty in 2014 at SashaCon; Mark Schierbecker photo under CC 3.0.

“Faith is the excuse people give for believing something when they don’t have evidence.”

— Dillahunty, "The Atheist Experience" Episode 696 (Feb. 13, 2011)

A.C. Grayling

On this date in 1949, British author, philosopher and atheist Anthony Clifford Grayling was born in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), where his father was a banker. He spent his childhood in Africa. When he was 19, his older sister Jennifer was murdered in Johannesburg. When her parents went to identify the body, her mother had a fatal heart attack. After earning a B.A., M.A. and Ph.D. in England, Grayling lectured in philosophy at Bedford College-London and St. Anne’s College-Oxford before taking up a post in 1991 at Birkbeck College-University of London, where he was a philosophy professor until 2011. He then founded and became the first master of New College of the Humanities.

Grayling is the author of over 30 books on philosophy, biography, the history of ideas, human rights and ethics, including The Refutation of Scepticism (1985), The Future of Moral Values (1997), Wittgenstein (1992), What Is Good? (2000), The Meaning of Things (2001), The Good Book (2011), The God Argument (2013), The Age of Genius: The Seventeenth Century and the Birth of the Modern Mind (2016), War: An Enquiry (2017) and Democracy and its Crises (2017). His 2006 play “Grace” was co-written with Mick Gordon. The title character is a science professor who rejects religion.

He’s a vice president of the British Humanist Association, an honorary associate of the National Secular Society and has held positions with many other academic and literary organizations. The awards bestowed on him are numerous, including the Order of the British Empire, and others honoring his contributions to philosophy and ethics. One current biographical source says that Grayling believes that religion for historical reasons has had influence far out of proportion to the number of adherents and its intrinsic merits, “with the result that they can distort such matters as public policy (e.g., on abortion) and science research and education (e.g., stem cells, teaching of evolution).”

In a 2013 interview, freethinker Sam Harris asked Grayling if “a person can be both a humanist and a person of faith?” Grayling replied, “No, religion and humanism are not consistent — unless you mean ‘humanism’ in the Renaissance sense, where it denoted the study of classical literature. But this study soon showed people that the ideas and outlook of classical thought is at odds with religion, which is why humanism is now a secular philosophy.”

He and his wife, novelist Katie Hickman, have a daughter, Madeleine, and a stepson, Luke. He also has a son, Jolyon, and a daughter, Georgina, from his first marriage.

“In the study of history I became aware of the effects of religious divisions and sectarianism on individuals and societies, and came to think that freedom from religious influence is a human rights issue. I am an atheist, a secularist and a humanist.”

— Grayling, interviewed by Sam Harris, samharris.org (March 30, 2013)

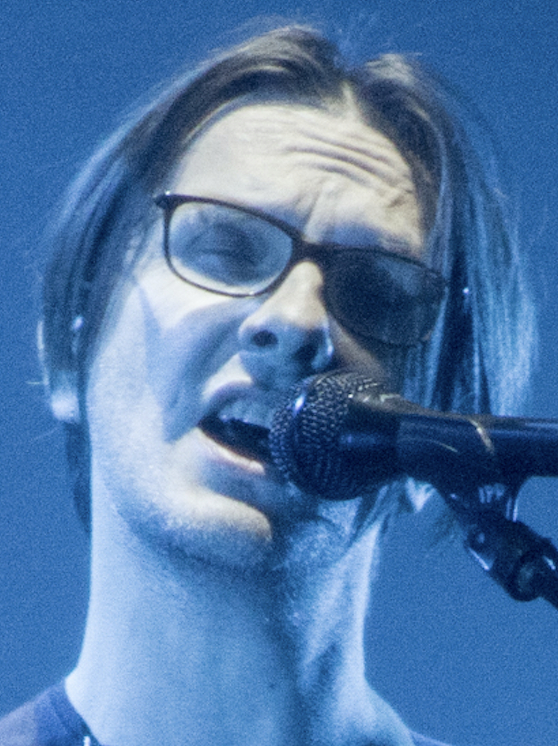

Shelley Segal

On this date in 1987, singer/songwriter Shelley Segal was born in Melbourne, Australia, to Jenny and Danny Segal in a traditional Jewish household. For years, her dad was president of the East Melbourne Hebrew Congregation, an Orthodox synagogue. He fronted a klezmer band that was often booked for celebrations of life-cycle events like bar and bat mitzvahs. Jenny, whom Shelley calls “Mum,” managed the band.

Displaying her own talent and surrounded by working musicians, Segal started sitting in with the group when she was 11, playing acoustic guitar and adding her voice to her dad’s. Her religious doubts started during school biology classes when the topic was evolution. “I probably called myself an atheist at 18, but I still thought religion was positive, if not for me. It was the beginning of learning to think critically.” (The Age, April 14, 2012)

“When I got some distance and perspective I saw things I might take issue with — women being separated [in synagogue] and not being allowed to take part in the service or lead the service and, looking back, it’s abhorrent to me that I didn’t see a problem. … When as a teenager I came home and said I didn’t believe in God, it must have felt like a complete rejection. The more I meet people in the movement and hear how hard it’s been for them, the more impressed I am by my family.” (Ibid.)

She released an EP composed of songs she wrote at ages 15–21 in 2009. “An Atheist Album” (2011) included the single “Saved.” It was the first time she’d ever written about her beliefs. “I was told very kindly and very politely by a preacher in the street that I was going to burn in hell forever. So I felt like I wanted to push back and say, ‘I won’t be told how to live my life.’ ” (FFRF’s “Freethought Matters,” Jan. 23, 2025)

“An Atheist Album” explored her beliefs and was hard for her dad to accept, she said, but they had reached common ground and could still play together. “My overall goals are to increase empathy and lessen suffering, humanist goals, those are things my dad can agree with me on.” (Melbourne Herald Sun, Feb. 27, 2013) One of their favorites to perform together is Leonard Cohen’s “Dance Me to the End of Love.”

Segal performed at the Reason Rally for religious skeptics in Washington, D.C., in 2012 and 2016, then moved to Los Angeles. By then she had released five recordings. Segal co-produced the 2023 single and video tribute “Mother” with her husband Rob J Robertson. Her dad played violin.

She opened Secret Sauce Studio & Production House in Los Angeles and has been a guest several times on FFRF media and at events, including the 2013 national convention and FFRF’s 2024 winter solstice celebration at Freethought Hall in Madison, Wis.

PHOTO: Courtesy of Shelley Segal.

What will it take for you

To start opening your eyes

To start questioning the bullshit everyone around you buys

You think it’s any of your business what goes on between my thighs?

I wonder, I wonder,

When we’ll be rid of your lies.— A verse from Segal's song "Saved"

Marjory Stoneman Douglas

On this date in 1890, Marjory Stoneman Douglas, who became one of the greatest environmental writers and activists of the 20th century, was born in Minneapolis, the only child of Frank Stoneman and Florence (Trefethen) Douglas. Her parents separated when she was 6 and she had an unsettled upbringing, with her mother suffering from mental illness. Her upbringing, she wrote in her 1987 autobiography, contributed to her becoming “a skeptic and a dissenter.” After graduating from Wellesley College in 1912 (her mother died when she was a senior), Douglas served in Europe during World War I with the American Red Cross.

She became an early feminist and vigorous civil rights activist. In 1916 she and others lobbied Florida legislators for women’s suffrage. She had moved to Florida and married Kenneth Douglas in 1914, a much older man who was later revealed to be a bigamist and con artist. She went to work for her father in 1915 at the paper that became the Miami Herald. From 1920 to 1990, Douglas published 109 fiction articles and stories.

She dedicated five years to her groundbreaking book The Everglades: River of Grass (1947). The book forever changed the way that Americans viewed wetlands and the relationship between Floridians and the Everglades. It was a best-seller and battle anthem for preservationists. She founded Friends of the Everglades in the 1960s and led the group for three decades. In 1993 she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton. She was inducted into the National Wildlife Federation Hall of Fame in 1999 and the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2000.

Although Douglas grew up in a religious household, she called herself an agnostic. In her autobiography she wrote, “The soul is a fiction of mankind, because mankind hates the idea of death. It wants to think that something goes on after. I don’t think that it does, and I don’t think we have souls. I think death is the end. A lot of people can’t bear that idea, but I find it a little restful, really.”

Before her death at age 108, she asked that there be no religious ceremony. (D. 1998)

PHOTO: Marjory Stoneman as a Wellesley senior.

“I believe that life should be lived so vividly and so intensely that thoughts of another life, or of a longer life, are not necessary.”

— Douglas' autobiography "Marjory Stoneman Douglas: Voice of the River" (1987)

Joseph Cunningham

On this date in 1926, freethinking educator and military “foxhole atheist” Joseph Cunningham was born into a religious and financially struggling family near Wadestown, W. Va. (population 50). The family of eight moved to Oklahoma, then to Michigan, where they lived in an abandoned rural grocery store, and then to Illinois, where Cunningham graduated from high school in Carmi.

He enlisted in the U.S. Navy, serving in the Pacific aboard the attack transport USS Bosque. After World War II he received $65 a month from the G.I. Bill to attend Southern Illinois University, where he graduated with a major in history and minors in English and business.

He taught for two years in a one-room school without electricity. After earning his master’s from SIU he taught a wide variety of subjects at Mascoutah High School, where he met his future wife Norma Steines Cunningham, also a teacher and religious skeptic. They married in 1953 and had two daughters, Kathryn and Linda, who were raised in a secular environment. The Cunninghams were married for 64 years until her death in 2018 at age 100.

Cunningham served on FFRF’s executive board of directors for 38 years. As a veteran, he was also very involved with bringing FFRF’s Atheists in Foxholes monument to fruition in Madison, Wis.

Another project he took up after retirement was the planting of thousands of daffodils along Illinois Route 4. And since they are perennials, the thousands have turned into millions. He was honored nationally on Earth Day in 2015 for his green thumb and by the city of Mascoutah and the Federated Garden Clubs of Missouri and Illinois.

“Oh that I could have become a freethinker earlier in life,” Cunningham said in a 2019 email. “I spent many a sleepless night thinking the world would end at any second and that possibly I would end up in a never-ending, burning hell because I had accidentally done something that an angry god disapproved.”

“Any good that I can do, let me do it now, for I shall not pass this way again.”

— Cunningham's quote to live by (October 2019 email)

Sam Harris

On this date in 1967, author and neuroscientist Samuel Benjamin Harris, a key figure in the 21st century freethought movement, was born in Los Angeles, the son of TV producer and writer Susan (Spivak) Harris and actor Berkeley Harris, who divorced when Sam was 2. He grew up in his mother’s secular household and enrolled at Stanford University to study philosophy but left during his sophomore year to study Eastern religions and meditation in India. He eventually returned to Stanford and graduated in 2000.

He started writing his first book, The End of Faith, after the Sept. 11 attacks in 2001. It received the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for First Nonfiction in 2005 and was followed by his Letter to a Christian Nation in 2006. Harris married in 2004 and has two daughters with his wife Annaka, an author and science editor. They co-founded the nonprofit Project Reason in 2007. He received a Ph.D. in cognitive neuroscience in 2009 from UCLA. Five of his books are New York Times bestsellers. His latest, as of this writing, are Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion (2014) and Islam and the Future of Tolerance (with British activist Maajid Nawaz, 2015).

Harris is generally considered a member of the “Four Horsemen of New Atheism” along with Richard Dawkins and the late Daniel Dennett and Christopher Hitchens. The name comes from the title of a video they made during a two-hour unmoderated discussion at Hitchens’ home on Sept. 30, 2007. Journalist Simon Hooper described New Atheism as “the view that superstition, religion and irrationalism should not simply be tolerated but should be countered, criticized and exposed by rational argument wherever its influence arises in government, education and politics.”

Harris has no use for the term New Atheism or for the atheist label. In a 2007 speech he said that while he had become “one of the public voices of atheism, I never thought of myself as an atheist before being inducted to speak as one. I didn’t even use the term in The End of Faith, which remains my most substantial criticism of religion. And, as I argued briefly in Letter to a Christian Nation, I think that ‘atheist’ is a term that we do not need, in the same way that we don’t need a word for someone who rejects astrology. We simply do not call people ‘non-astrologers.’ All we need are words like ‘reason’ and ‘evidence’ and ‘common sense’ and ‘bullshit’ to put astrologers in their place, and so it could be with religion.”

PHOTO: By Christopher Michel under CC 4.0.

“It is time that we admitted that faith is nothing more than the license religious people give one another to keep believing when reasons fail.”

— Harris in "Letter to a Christian Nation" (Knopf, 2006)

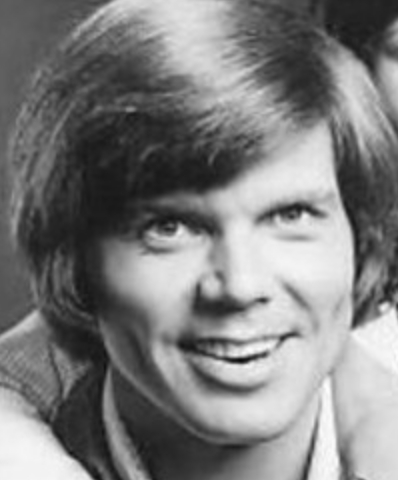

Jimmy Dunne

On this date in 1934, atheist activist Jimmy Charles Dunne was born in Houston, Texas, to Frieda (née Yost) and Julius Dunne. His mother was a Nebraska-born nurse who met his father in Chicago, where he was studying to be a podiatrist, a quest he gave up during the throes of the Depression and eventually founded a successful advertising company employing several salesmen.

The eldest of five children, he remembers his father taking them to Catholic Mass on Sundays. “As a teenager, I had doubts about religion — from Mary, mother of Jesus, being a virgin to the pope being infallible,” he said at age 90, describing himself as “a 100 percent atheist and a humanist.”

After high school graduation, he worked for a summer at a men’s clothing store before enrolling in 1952 at Texas A&M, an all-male college without enough social life to suit him. He transferred after a year to the University of Houston, where he graduated. He then worked in New Orleans in the U.S. Department of Labor’s wage and hour division.

He tamed his fear of public speaking by completing a Toastmasters International course, then started teaching math in middle school in Houston while operating a singles dance club during his off hours at various venues for three years starting in 1961.

Using corporal punishment to spank recalcitrant students bothered him as cruel and ineffective, so he founded People Opposed to Paddling Students (POPS) and started speaking out, appearing on “The Phil Donahue Show,” “Good Morning America” and other shows. He addressed school boards, the Texas Legislature and a U.S. congressional committee on the need to put away the paddles. Newsweek magazine detailed his efforts in a story on June 22, 1987.

As he detailed in a January 2025 speech titled “From Introvert to Extrovert to Atheist” to the Unitarian Fellowship of Houston, once when President Jimmy Carter came to Houston, Dunne asked him if using wooden boards on students constituted child abuse. The president replied that they had spanked their sons but stopped the practice after daughter Amy was born. Corporal punishment in schools is still legal in Texas and several other states as of this writing in 2025.

His career also includes service in the U.S. Army and employment with the Interstate Commerce Commission in Washington, D.C. He and his first wife Lindacarol, who worked as a draftsperson, married in 1968 and had a daughter Melody (b. 1971). Divorcing after 10 years, he married Melinda, a junior high English teacher who died from uterine cancer in their 21st year of marriage. He and Karen, his third wife, met at a current events discussion group and are divorced but still living together.

Dunne, an inveterate letter writer on behalf of progressive causes, served for five years as president of Humanists of Houston, led a local Amnesty International chapter and still gathers regularly with a lunch group called the Hungry Heathens. He supports the Freedom From Religion Foundation as a Life Member “for all the enlightenment they are doing through education and taking on legal issues concerning separation of church and state.”

His activism has involved campaigning against long-term solitary confinement in prison and working with the Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty. He credits Pope Francis for “inching” the church forward in a few regards but roundly criticizes it for barring gay marriage, birth control and female clergy. “It’s good that we have ‘cafeteria Catholics’ who pick and choose which pronouncements they will honor.”

“The Catholic Church is like a turtle. It moves very slowly, dropping poop along the way that followers must step in. … The church has lied for centuries claiming that there is a God, a heaven and a hell, when there is no evidence that they exist.”

— Dunne letter to the editor, Houston Chronicle (Dec. 31, 2023)

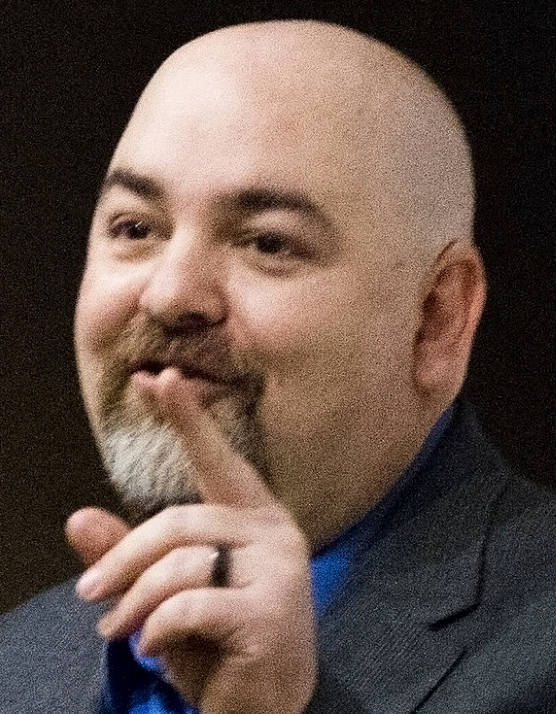

Anthony B. Pinn

On this date in 1964, humanist scholar Anthony Bernard Pinn was born to Raymond and Anne Pinn in Buffalo, N.Y. He grew up going to Baptist and African Methodist Episcopal (AME) churches and decided that he was going to be a minister. He preached his first sermon from the pulpit at age 12 and later transferred from public school to a Southern Baptist high school before enrolling at Columbia University, where he earned a B.A. He worked as an AME youth pastor in Brooklyn and Boston but started to believe that the church had no real answers to people’s problems. “I was moving from this kind of evangelical fundamentalist position to something more along the lines of the social gospel, but it still wasn’t getting it done.” (October 2014 speech at the Freedom From Religion Foundation’s national convention.)

Continuing his studies, he earned a master of divinity degree and a Ph.D. in philosophy from Harvard in 1994. His dissertation title was “ Wonder as I Wonder: An Examination of the Problem of Evil in African-American Religious Thought.” He had been questioning whether God existed and was having issues with theism more than religion. He asked himself, “Do the people matter, or is it the tradition that matters?” He relinquished his minister’s credentials, remaining interested in religion but seeing it as “a force that needed to be wrestled with and understood as a cultural development that shaped world events in some profound ways.” In his first book, Suffering and Evil in Black Theology (1995), Pinn discussed theodicy (why God permits evil) from an African-American perspective. How, he asked, can black theists, particularly black theologians, make sense of a perfect, benevolent God in light of African-American suffering?

After teaching at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, Suffolk University and Macalester College, he accepted an offer in 2003 from Rice University in Houston, becoming the first African-American to hold an endowed chair there as a professor of humanities and religion. Pinn is the founding director of the Center for Engaged Research and Collaborative Learning at Rice and director of the Institute for Humanist Studies in Washington. He’s the author, co-author or editor of more than 35 books, including the Fortress Introduction to Black Church History (with his mother, Anne H. Pinn, an AME minister, in 2001), The End of God-Talk: An African American Humanist Theology (2011), Writing God’s Obituary: How a Good Methodist Became a Better Atheist (2014), Humanism: Essays in Race, Religion, and Cultural Production (2015) and When Colorblindness Isn’t the Answer: Humanism and the Challenge of Race (2017).

His awards include the African-American Humanist Award from the Council for Secular Humanism (1999), Harvard University Humanist Association Humanist of the Year (2006) and Unitarian Universalist Humanist Association Humanist of the Year (2017). He was named a recipient in 2019 of FFRF’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award for speaking truth to power. Pinn’s research interests include humanism and hip hop culture. He married journalist Cheryl Johnson in 2000. They separated in 2005 and divorced in 2015.

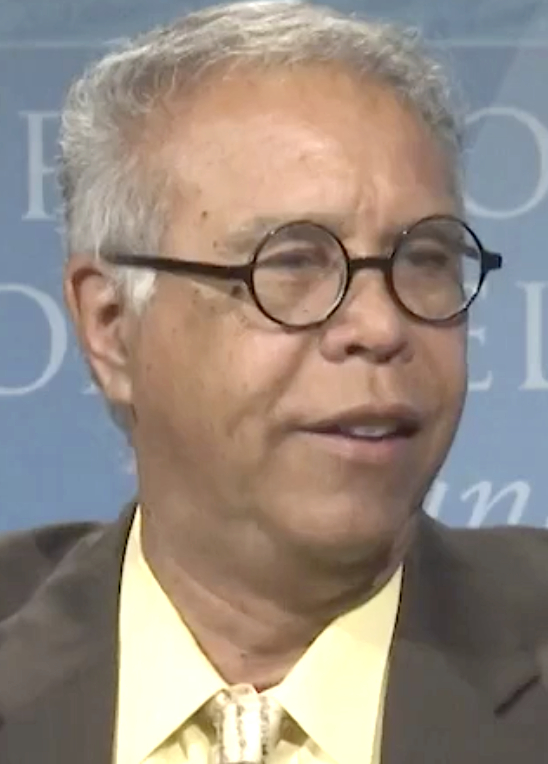

PHOTO: Pinn receiving FFRF’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award; Ingrid Laas photo.

“For me the title is a way of capturing the decline and eventual death of a concept — God — that had been important to me for years. I wanted the title to reflect my transition from theism to nontheistic humanism through my push away from God — God being the central category of my religious youth.”

— Anthony Pinn, interview, Religion News Service, April 1, 2014, on his book "Writing God’s Obituary: How a Good Methodist Became a Better Atheist"

Richard E. Grant

On this date in 1957, actor Richard E. Grant (né Richard Grant Esterhuysen) was born in Mbabane, the capital of Swaziland when it was a British protectorate and his father Henrik was the nation’s director of education. He had a tough childhood. Henrik was an alcoholic who could become abusive, and his mother Leonne ran off with her husband’s best friend not long after Richard saw them having sex in the back seat of a car when he was 10. Henrik shot at Richard one night and “then passed out. He didn’t remember it the next day,” Richard said. He told The Independent in 2006 that he was estranged from his younger brother Stuart.

After studying English and drama at the University of Capetown and joining an acting company there, he moved to England in 1982, the year after Henrik died at 51 of cancer. He made his film debut in the drama “Withnail and I” (1987), followed by film roles in “L.A. Story” (1991), “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” (1992), “Gosford Park” (2001), “The Iron Lady” (2011) and “Logan” (2017). He was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his performance in “Can You Ever Forgive Me?” (2018). On television, he played Bob Cratchit in TNT’s “A Christmas Carol” (1999) and appeared in “Star Wars: Episode IX” (December 2019 release).

Grant has written three books and started marketing a line of Jack perfumes in 2014. He married voice coach Joan Washington, eight years his senior, in 1986. They have a daughter, Olivia, and she has a son, Tom. He described himself in April 2014 to The Telegraph newspaper as a “confirmed atheist.”

In February 2000 he told The Daily Mail that, “Like [my father], I absolutely believe in the here and now. I have no expectation that there’s anything beyond. Life’s to be grabbed with every fibre of your being.” In October 2005, he told The Times of London that although his wife is a Christian, she encouraged their daughter to make up her own mind: “Like me, she came to the conclusion that both Heaven and Hell are here on Earth.”

PHOTO: Grant in 2018; photo by Greg2600 under CC 2.0.

“I took a comparative religion course when I was at university to get an overview, but it had no impact whatsoever. As far as I’m concerned, Darwin has come up with the best theory of how, when and why we are here. Nothing else has convinced me otherwise.”

— Grant interview, The Times of London, Oct. 29, 2005

Margaret Cole

On this date in 1893, English socialist, politician and poet Margaret Isabel Cole (née Postgate) was born in Cambridge, England, to John and Edith (Allen) Postgate. They raised her with a well-rounded education at Roedean School and Girton College, Cambridge. During her time at Girton, Cole was inspired by the works of intellectuals such as J.A. Hobson, H.G. Wells, Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, George Bernard Shaw and Noel Brailsford.

These readings led her toward a life of socialism, feminism and atheism and away from her conventional Anglican upbringing. Cole became a classics teacher at St. Paul Girls School at Cambridge. Her brother shared some of her interests and was imprisoned during World War I as a conscientious objector.

While working with the No-Conscription Fellowship, she met George Cole, who led a movement known as Guild Socialism. They married in 1918 and joined the socialist Fabian Society before moving to Oxford in 1924. During their time there they taught, co-authored numerous mystery novels and created the Socialist League. Although she was anti-World War I, she espoused military action in the 1930s after witnessing the rise of Hitler and the Nazi Party.

In 1949, her autobiography, Growing Up Into Revolution, was published. She wrote many other books, including a biography of her husband.

Cole was committed to the well-being of London’s citizens and came to be a founding member of the Inner London Education Authority in 1965, where she remained until 1967, when she retired. She received the Order of the British Empire in 1965, the equivalent of being knighted for men, and thus became Dame Margaret Cole. She used her academic exposure to introduce comprehensive education in London throughout the rest of her life. (D. 1980)

PHOTO: Reproduction of a Cole portrait by Australian artist and feminist Stella Bowen, c. 1944.

“[Conscientious objection] on religious grounds was for most part treated with respect, particularly if the sect had a respectable parentage. … But non-Christians who objected on the grounds that they were internationalists or Socialists were obvious traitors in addition to all their other vices, and could expect little mercy.”

— Margaret Cole, "Growing Up Into Revolution" (1949)

Juan Mendez

On this date in 1985, community activist and state legislator Juan Mendez was born in Arizona. A first-generation American, he graduated from high school in Tolleson, a Phoenix suburb, and from Arizona State University with a major in political science and minor in justice studies. He then worked as political coordinator for Iron Workers Local 75 and as a program instructor for the Boys and Girls Club of the East Valley. From 2009-13, he ran the nonprofit Arizona Community Voice Mail to help connect the homeless to jobs, housing, information and hope.

Mendez burst into the national consciousness after being elected in 2012 to the Arizona House of Representatives from District 26. The 240 words of his secular invocation to open a House session caused quite a stir on May 21, 2013.

Such a “nonprayer” in a statehouse was unheard of at the time. Mendez also introduced Secular Coalition for Arizona members sitting in the gallery. One member said later she was “witnessing history.” In recognition of Mendez’s courage, FFRF bestowed on him its Emperor Has No Clothes Award, which he accepted at the 2013 national convention in Madison, Wis. After Gov. Jan Brewer signed an executive order in August 2014 to create the Governor’s Office of Faith and Community Partnerships, Mendez joined a group at the Capitol to criticize the office.

He was reelected in November 2014 and became involved in another invocation controversy in 2016. After he had signed up in January to give an invocation, House Majority Leader Steve Montenegro blocked him, saying all invocations had to be made to a “higher power” and even barring moments of silence. Mendez then used his right in February to make personal comments from the floor to offer a secular invocation after the official prayer, saying the state’s diversity includes people of different religions “and lack thereof. We need not tomorrow’s promise of reward to do good deeds today.”

Early in the next month, he offered another, after which Montenegro said that because Mendez didn’t invoke God, a Baptist minister would, calling Mark Mucklow to the podium. “At least let one voice today say ‘Thank you, God bless you,’ ” Mucklow proclaimed at the end of his prayer.

Mendez was elected to the state Senate in 2016, 2018 and 2020. He and his wife, state Rep. Athena Salman, have a daughter, Nausicaa Mendez Salman, born in January 2022. They were both reelected in November 2022.

PHOTO: by Brent Nicastro

“I am an atheist because I’ve found no faith in any deity from Thor to Zeus. I am so grateful for the work the people in this room have done to advance the separation of state and church, to educate communities, to build a culture that made it possible for me, as a state legislator from Arizona, to talk honestly about what I do and don’t believe in.”

— FFRF convention speech, Sept. 27, 2013

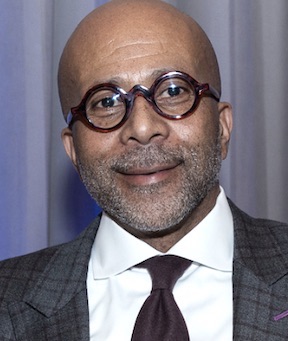

José Mujica

On this date in 1935, José Alberto Mujica Cordano, 40th president of Uruguay, was born in Montevideo. When Mujica was 7, his farmer father went bankrupt and died shortly after. Mujica worked delivering baked goods and as a teen was an avid bicyclist. Politically involved as a youth, he joined the Tupamaros, revolutionaries fighting Uruguay’s brutal dictatorship in the 1960s. He was imprisoned for 14 years, many spent in solitary confinement. He was freed in 1985, as the dictatorship waned, under a general amnesty.