editors

Robin Morgan

On this date in 1941, Robin Morgan — feminist author, journalist, editor, lecturer, organizer, atheist and activist — was born in New York City. As she notes in her memoir, Saturday’s Child, “Saturday’s child has to work for a living.” She started at age 2 as a tot model. She had her own radio show by age 4, then acted in the role of Dagmar on the popular series “Mama” in the 1940s and 1950s. She left show biz to write and became a founder and leader of the contemporary feminist movement.

Morgan’s columns and articles for Ms. magazine appeared from 1974-88. She was editor-in-chief of Ms. for four years and later its international consulting editor. Her groundbreaking anthology Sisterhood Is Powerful came out in 1972, followed by Sisterhood Is Global (1984), Sisterhood Is Forever (2003) and Fighting Words: A Toolkit for Combating the Religious Right (2006). Morgan is a distinguished poet and the author of more than 20 books, including her 2006 novel The Burning Time, based on the first witchcraft trial in Ireland.

She has traveled the globe as a feminist activist, scholar, journalist and lecturer. She is a co-founder of the Feminist Women’s Health Network, the Feminist Writers’ Guild, Media Women and the National Network of Rape Crisis Centers. Her timely The Demon Lover: On the Sexuality of Terrorism tells the personal story of her travel to refugee camps in the Middle East, with a post-9/11 introduction and afterword. A recipient of many awards, she was named FFRF’s Freethought Heroine in 2005 and is an honorary director.

She was married from 1962-83 to poet Kenneth Pitchford, a founding member of the Effeminist movement. He and Morgan, who are both bisexual, have a son, musician Blake Morgan.

She was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2010. Instead of curtailing her effectiveness, the diagnosis inspired her to take the lead in creating the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation’s Women and PD Initiative to help women be better served by research, treatment and assistance for their caregivers. Morgan has shared her struggle with the disease by writing and presenting about her experiences at a variety of venues, including her 2015 Ted Talk, viewed over a million times. In 2018 she published Dark Matter: New Poems, which includes the verses from that presentation.

“Religion is not about awe and joy, despite its purported proprietorship of these and its promise to eventually deliver what already lies around us every day, freely available for utter celebration. Religion is about something else. The etymology of the word itself, from the Latin, to being ‘bound by rules.’ Religion is about terror.”

— Freethought Heroine acceptance speech at FFRF's national convention (Nov. 11, 2005)

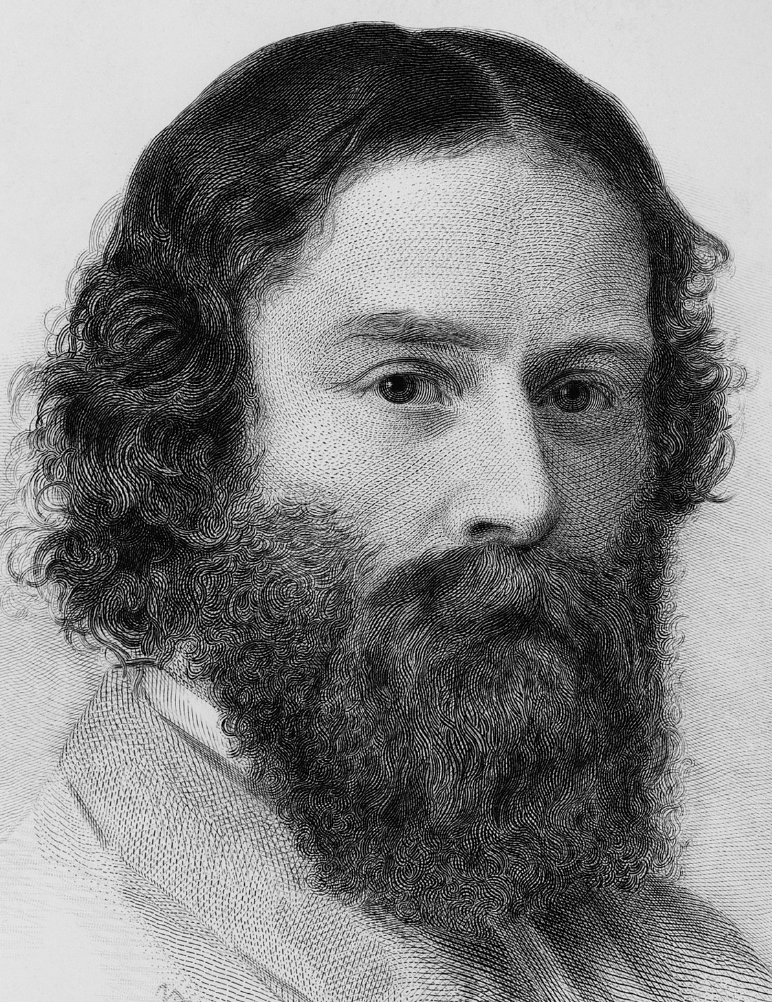

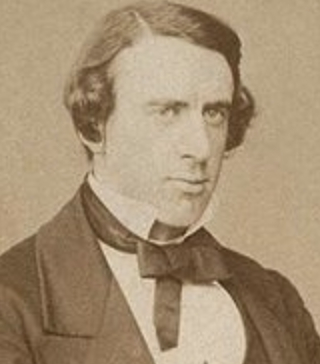

James Russell Lowell

On this date in 1819, poet James Russell Lowell was born in Cambridge, Mass., the son of a Unitarian minister in a family which went back eight generations in America. Lowell was one of the “Fireside Poets,” a group of New England writers that included Longfellow, Whittier and Holmes. Lowell earned his B.A. in 1838 and his L.L.B. in 1840 from Harvard. An ardent abolitionist, he left the law for literature, editing several journals.

He edited the Atlantic Monthly (1857-61) and the progressive North American Review (1864-72). A professor at Harvard for nearly 20 years, he also served as a minister to Spain and Great Britain. The poet wrote A Fable for Critics (1848), The Biglow Papers (serialized articles published in book form in 1848 and 1867) and The Vision of Sir Launfal (“And what is so rare as a day in June?”) in 1848.

Although Lowell’s poetry contains religious views that were conventionally 19th-century Unitarian, rationalist biographer Joseph McCabe suggested that, based on his later remarks, Lowell became agnostic. His later poetry included “The Cathedral “(1870), which dealt with the conflicting claims of religion and modern science.

He married the poet Maria White in 1844. They had four children, only one of whom survived childhood, before she died in 1853. He married Frances Dunlap in 1857. She died in 1885, six years before his death in 1891 at age 72.

“Toward no crimes have men shown themselves so cold-bloodedly cruel as in punishing differences of belief.”

— Lowell, "Literary Essays, Vol. II: Witchcraft" (1891)

William Stewart Ross

On this date in 1844, William Stewart Ross (“Saladin”) was born in Scotland. While preparing for the ministry at Glasgow University, Ross became a rationalist and gave up the church. He set up his own publishing company, W. Stewart & Co., in London. By 1880 he was co-editor of the Secular Review. Later becoming its sole editor and owner, he changed the name to the Agnostic Journal and Secular Review in 1889 and shortly thereafter to the Agnostic Journal and Eclectic Review. The last issue was published in June 1907.

Ross was not an admirer of the famous British atheist Charles Bradlaugh, and his journal and essays represented an alternative style. He wrote under the nom de plume of “Saladin” (the Muslim fighter who halted the Third Crusade). His books include God and His Book (1887) and Woman: Her Glory and Her Shame (two volumes, 1894). In 1879 he won a gold medal for writing the best poem to memorialize the unveiling of a statue of Robert Burns. Confined in his last years due to sclerosis, he died in 1906 at age 62.

“Christianity claims to have originated lunatic asylums. If I were to claim that it was I who made the moons of Jupiter and placed the belt round Saturn, I should be nearly as preposterous as Christianity is when she claims to have originated asylums for the insane. … If the preacher would stand up in his pulpit and whine, ‘My dear Christian brethren, our blessed religion did not originate lunatic asylums; but it has made up for that by making millions of lunatics,’ he would speak only the sober truth.”

— W.S. Ross, Chapter XXXII, "God and His Book" (1887)

Vladimir Pozner Jr.

On this date in 1934, Vladimir Vladimirovich Pozner was born in Paris to a Russian-Jewish father, also named Vladimir, and a French Catholic mother, Géraldine Lutten. The couple separated when he was 3 months old, and he and his mother moved near her family in New York City. His parents later reunited and moved back to Paris in 1939.

Fleeing World War II, they returned to New York in 1940. Pozner briefly attended Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan until his father, under FBI scrutiny for pro-Soviet activities and suspected spying, moved them to East Berlin and then to Moscow. He majored in human physiology at Moscow State University and earned a B.S. in 1958.

In 1961 he joined Novosty Press Agency (later learning his department was actually a KGB “disinformation” effort) and then became editor of Soviet Life and Sputnik magazines. He was a commentator on Radio Moscow from 1970-86. Pozner was permitted to travel abroad from 1977 to 1980, when his passport was revoked for criticizing Russia’s military incursions in Afghanistan.

In the late 1980s he began appearing regularly on ABC’s “Nightline,” the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the BBC and other TV networks in the U.S. and abroad, all by satellite hookup because he was not allowed to travel. In 1985-86 he co-hosted two shows, also by satellite, with Phil Donahue, which brought glasnost to Soviet TV. In 1989, he resigned from the Communist Party.

He moved to New York City in 1991 to work with Donahue. Parting with Illusions (1990) became a national best-seller, which was followed by Eyewitness (1991). In 1997, Pozner returned to Moscow to host two TV shows. He served as president of the Academy of Russian Television and dean of the Pozner School of Television Journalism. He has won two Emmy certificates and several other journalism awards.

He married Valentina Chemberdzhi (1957–67), Yekaterina Orlova (1969–2005) and Nadezhda Solovieva (2005). He has often identified himself publicly as an atheist and has advocated for the right to euthanasia and legalization of same-sex unions and recreational drugs in order to cut down on trafficking.

“As it is known, I am an atheist. I stridently believe there is no God. It’s not that I run around shouting, ‘There isn’t, there isn’t’ from morning to evening, but I do not hide my convictions.”

— Pozner interview with Radio Free Europe (May 16, 2017)

Elihu Palmer

On this date in 1764, Elihu Palmer was born in Canterbury, Conn. Palmer graduated from Dartmouth in 1787, read theology and proved to be an unpopular minister in Presbyterian and Baptist congregations, where he spoke as a deist against the divinity of Jesus Christ. He switched to law and was admitted to the bar in Philadelphia in 1793. Yellow fever had killed his young wife and blinded Palmer.

He was invited to found the Deistical Society of New York, and lectured widely on the East Coast. He wrote orations, opinion pieces and the book Principles of Nature; or, A Development of the Moral Causes of Happiness and Misery Among the Human Species (c. 1801), in which he wrote that “the world is infinitely worse” for following Jesus.

Palmer also founded Prospect, a journal that was published from 1803-05. Unlike many deists, Palmer argued that the flawed teachings of Jesus were responsible for Christianity’s sordid history. According to Roderick C. French’s entry in Encyclopedia of Unbelief, Palmer wrote that he preferred “the correct, the elegant, the useful maxims of Confucius, Antoninus, Seneca, Price and Volney.”

When Thomas Paine was universally ostracized for writing The Age of Reason, Palmer and his second wife, who nursed Paine, remained steadfast friends. Palmer was only 42 when he died during a speaking tour. D. 1806.

“Another important doctrine of the Christian religion, is the atonement supposed to have been made by the death and sufferings of the pretended Saviour of the world; and this is grounded upon principles as regardless of justice as the doctrine of original sin. It exhibits a spectacle truly distressing to the feelings of the benevolent mind, it calls innocence and virtue into a scene of suffering, and reputed guilt, in order to destroy the injurious effects of real vice.”

— Palmer, "Principles of Nature" (1801)

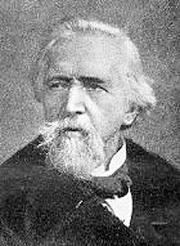

Abner Kneeland

On this date in 1774, Abner Kneeland was born in Massachusetts to a Congregationalist family. As a founding member of the Universalists, he served as a minister from 1804-29. When freethinker Frances Wright embarked on her famous lecture tour, becoming the first woman to speak in public in the U.S., New York City halls were closed to her. Kneeland invited her to speak from the pulpit of his Second Universalist Society in 1829, consequently lost his position and was later disfellowshipped by the church.

Kneeland’s lectures against Christianity in August 1829 were published as A Review of the Evidences of Christianity. He founded a group of freethinking New Yorkers, which met in Tammany Hall for a decade. Kneeland’s Rationalism of the Enlightenment made him a leading proponent of universal public education and the Workingmen Party.

Moving to Boston in 1830, Kneeland founded the Boston Investigator, the oldest 19th-century freethought newspaper in the U.S. His Sunday lectures to the First Society of Free Enquirers attracted crowds and the attention of influential critics. He was charged with blasphemy in 1834 for saying he did not believe in God, undergoing three trials. The prosecuting attorney for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts told the jury that if Kneeland was not punished, “marriages [will be] dissolved, prostitution made easy and safe, moral and religious restraints removed, property invaded, and the foundations of society broken up, and property made common.”

His appeal to the state Supreme Court ended with a split verdict of guilty in 1838 and he served a 60-day sentence. He moved to Iowa Territory, co-founding a freethinking settlement known as Salubria (near present-day Farmington) and becoming chair of the Van Buren County Democratic convention in 1842. An anti-infidel opposition party burned Kneeland in effigy and defeated his ticket, which was known by missionaries as “Kneelandism.”

His versatile writings included a popular spelling reader, an annotated New Testament, an edition of Voltaire‘s Philosophical Dictionary, and the two-volume The Deist (1829). D. 1844.

“Universalists believe in a god which I do not; but believe that their god, with all his moral attributes, (aside from nature itself,) is nothing more than a chimera of their own imagination.”

— Kneeland letter to Universalist editor Thomas Whittemore, Boston Investigator (Dec. 20, 1833)

George Jacob Holyoake

On this date in 1817, George Jacob Holyoake was born to a poor family in England. The young foundry worker attended classes in his free time, becoming a mathematics teacher. By 1840, Holyoake was a lecturer at the Worcester Hall of Science. Best-known for coining the term “secularist,” Holyoake dedicated his life to freethought. He was sentenced to six months in jail for saying England was “too poor” to support a God and should consider retiring him. He founded and edited a number of freethought journals, including Reasoner (1846-50), Leader (1850) and Secular Review (1876).

Holyoake wrote more than 160 pamphlets and works, including the books Origin and Nature of Secularism (1896), his autobiography, Sixty Years of an Agitator’s Life (1892), and the two-volume Bygones Worth Remembering (1905). He was president of the British Secular Union for many years, and became the first chair of the Rationalist Press Association.

As an Owenite, Holyoake was an ardent reformer who put causes over personal gain, helped work for women’s rights, political and educational reform, and personally aided refugees fleeing persecution. Contemporary American agnostic Robert G. Ingersoll wrote on Aug. 8, 1888: “There is no man for whom I have greater respect, greater reverence, greater love, than George Jacob Holyoake.” (D. 1906)

“Free thought means fearless thought. It is not deterred by legal penalties, nor by spiritual consequences. Dissent from the Bible does not alarm the true investigator, who takes truth for authority not authority for truth.”

— Holyoake, "The Origin and Nature of Secularism" (1896)

A. Philip Randolph

On this date in 1889, labor organizer, civil rights activist and journal editor Asa Philip Randolph was born in Crescent City, Florida, to parents James and Elizabeth (Robinson) Randolph. Growing up in Jacksonville, Randolph’s intellectual curiosity was shaped by his father, who, though a Methodist minister, encouraged him and his brother James to read freethought works. Through fireside debates about the existence of God with James and father, Randolph found that no logical conclusion of the affirmative or negative could be reached.

After high school he held a series of jobs, but facing discrimination, moved to New York City in 1911 to pursue an acting career, helping to establish the Shakespeare Society in Harlem and playing several title roles. When his parents disapproved of his acting career, Randolph enrolled at City College of New York in 1911, studying literature and sociology. Although he did not complete his degree, his political philosophy influenced his civil rights activism. Randolph believed that the root of racism was economic inequality. He began public speaking and founded the radical black magazine The Messenger in 1917.

Randolph went on to organize a union of New York City elevator operators and Virginia shipyard workers as president of the National Brotherhood of Workers of America. One of his greatest achievements was organizing the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) in 1925, which became the nation’s first all-black union. The U.S. government named him one of the “most dangerous Negroes” in America as a result of his outspokenness. Traveling around the country to establish new union chapters, Randolph became a skilled orator, speaking out to end Pullman Company’s unfair treatment of black railroad employees.

In 1941, Randolph planned a march on Washington to protest employment discrimination and segregation of the armed forces. Though the march wasn’t held, it helped spur passage of the Fair Employment Act. When President Truman called for a peacetime draft in 1947, Randolph continued to pioneer nonviolent civil disobedience, again threatening a march on Washington. This led to an executive order, which finally ended racial segregation in the U.S. military.

In the 1950s he allied with Martin Luther King Jr. With MLK’s assistance in 1957, Randolph orchestrated a prayer pilgrimage to Washington to peacefully demand that Southern schools comply with the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision ordering school integration. Randolph was a chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. An event typically considered the pinnacle of the civil rights movement, the march was attended by 250,000 people. It created momentum leading to passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

At age 74 he introduced MLK’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech, saying of the event, “This is the most beautiful day of my life.” (A. Philip Randolph: A Biographical Portrait by Jervis Anderson.) In 1964 he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Soon after, he founded the A. Philip Randolph Institute to study and ameliorate the causes of poverty, appearing at the White House in 1966 to propose a solution he termed the “Freedom Budget.”

Although he recognized the power of using religious rhetoric to motivate people to take action, Randolph’s secular humanist philosophy rankled some leaders of the civil rights movement. The American Humanist Association named him Humanist of the Year in 1970. He signed a public declaration of humanist principles, the Humanist Manifesto II, in 1973. Randolph married Lucille Campbell Green in 1913. (D. 1979)

“Prayer is not one of our remedies; it depends on what one is praying for. We consider prayer nothing more than a fervent wish; consequently the merit and worth of a prayer depend upon what the fervent wish is.”

— Randolph, from the mission statement of his magazine, The Messenger

Robert Gottlieb

On this date in 1931, Robert Adams Gottlieb, writer and editor at Simon & Schuster, Alfred A. Knopf and The New Yorker, was born in New York City to Charles and Martha Gottlieb. Growing up, he “was your basic, garden-variety, ambitious, upwardly mobile, hard-working Jewish boy from Brooklyn,” Gottlieb later wrote. His parents were “confirmed atheists” and religion played no part in his upbringing.

He enrolled at Columbia University as an English major, read voraciously (favorites: Henry James and Proust) and co-edited the school’s literary magazine. He graduated in 1952, the year he married Muriel Higgins when she was pregnant with their son and then studied abroad at Cambridge University before joining Simon & Schuster as an editorial assistant in 1955. Two years later he started editing the unknown Joseph Heller‘s manuscript that became the blockbuster titled Catch-22. (He thinks Heller’s Something Happened [1974] is his finest novel, “indeed, one of the finest novels of his time.”)

Gottlieb’s talent and nose-to-the-grindstone work ethic landed him the top editor position at S&S, where he stayed until moving to Alfred A. Knopf in 1968 as editor-in-chief. In 1969, four years after his divorce, he married Maria Tucci, an actress whose father, novelist Niccolò Tucci, was one of his writers. They had two children. In 1987 he succeeded William Shawn as editor of The New Yorker, where Gottlieb was succeeded in 1992 by Tina Brown. He then returned to Knopf as editor-ex officio.

Gottlieb also edited novels by John Cheever, Doris Lessing, Chaim Potok, Charles Portis, Salman Rushdie, John Gardner, Len Deighton, John le Carré, Ray Bradbury, Elia Kazan, Michael Crichton and Toni Morrison. He edited nonfiction books by Bill Clinton, Janet Malcolm, Katharine Graham, Nora Ephron, Katharine Hepburn, Barbara Tuchman, Jessica Mitford, Robert Caro, Antonia Fraser, Lauren Bacall, Liv Ullman, singer Paul Simon, Bob Dylan, Bruno Bettelheim and many others.

He served as the dance critic for The New York Observer starting in 1999 and was the author of biographies of George Balanchine, Sarah Bernhardt and the family of Charles Dickens (who had 10 children). For many years he was associated with the New York City Ballet and published books by Mikhail Baryshnikov and Margot Fonteyn. His autobiography Avid Reader: A Life was published in 2016. He died at age 92 in a New York City hospital. (D. 2023)

“I’ve simply always lacked even the slightest religious impulse — when people talk about their faith, I can’t connect with what they’re talking about. This isn’t a decision I came to, or a deep belief or principle; I’m just religion-deaf, the way tone-deaf people hear sounds but not music. I suppose my religion is reading.”

— Robert Gottlieb, "Avid Reader: A Life" (2016)

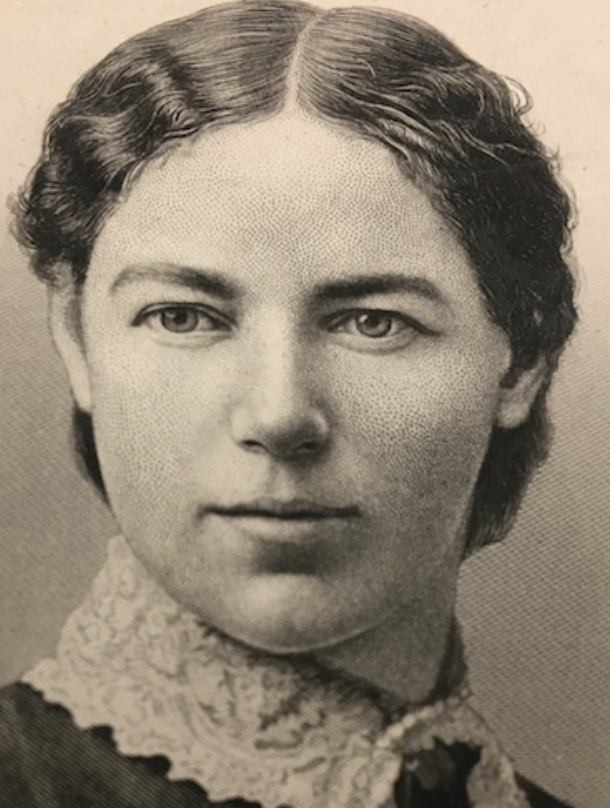

Clara Bewick Colby

On this date in 1846, Clara Dorothy Bewick (later Colby) was born in Cheltenham, England. She moved with her parents when she was 8 to a farm near Windsor, Wis. As an early reader, she liked to memorize and recite and churned butter by keeping time to fearful hymns threatening “the hells of fire,” she recalled in a lecture. At 19, she moved to Madison and enrolled at the University of Wisconsin. Graduating in 1869 as valedictorian, she was instrumental in opening admission of the UW to women.

She taught history and Latin at the UW, then married Leonard Wright Colby in 1871 and moved to Beatrice, Nebraska. She served for 16 years as president of Nebraska’s Woman’s Suffrage Association. She founded The Woman’s Tribune in 1883 and published that organ of the National Woman Suffrage Association for 25 years, including daily editions through the suffrage conventions. As editor she also set type, was compositor and sometimes ran the press.

Legendary for her energy and work ethic, Colby and her husband adopted two children, including a Lakota Sioux infant, “Lost Bird,” found by Leonard in the arms of the girl’s slaughtered mother after Wounded Knee. Her husband later abandoned the family with the child’s nursemaid and they divorced in 1906. Colby raised the child by herself.

Colby was the first woman designated as a war correspondent during the Spanish-American War. She lectured in nearly every state for suffrage, as well as England, Ireland and Scotland. Colby belonged to the Congregational Church but introduced and defended resolutions denouncing patriarchal religious dogma, notably at the 1885 woman suffrage convention. She routinely featured her friend Elizabeth Cady Stanton‘s critiques of religion on the front pages of The Woman’s Tribune.

She died at age 70 of pneumonia and myocarditis in Palo Alto, Calif., and her ashes are buried in the Congregationalist cemetery near her childhood home in Windsor, Wis. (D. 1916)

Horace Seaver

On this date in 1810, Horace Seaver was born in Boston. At age 28, he became a compositor at The Boston Investigator and learned the craft of printing. Seaver also began writing editorials under the name “Z.” The Investigator had been launched in 1830 by Abner Kneeland as a weekly, becoming the most effective and prominent freethought newspaper in the U.S., continuously published until 1904 when it merged with The Truth Seeker. When Kneeland, who had been prosecuted for blasphemy more than once, resigned, Seaver was selected to become its editor.

He edited the paper for the next half-century, promoting freethought, the working class and other secular reforms. He wrote Occasional Thoughts of Horace Seaver from Fifty Years of Free Thinking (1888). When his freethinking wife died, Seaver held a “social funeral,” an innovative model of the modern secular memorial service. When Seaver himself died, his funeral oration was given by the great 19th-century freethinker Robert G. Ingersoll. (D. 1889)

“We have secured some political freedom — I mean for such of us as have white complexions and are sound in the faith — but with regard to mental freedom, we are to the present hour almost literally in bondage to this potent spell, Authority. Men and women really dare not think for themselves, because they are fearful of some book or some church, some sect or some creed, that stands in the way.”

— Remarks by Seaver at the Free Convention in Rutland, Vermont (July 21, 1858)

Chapman Cohen

On this date in 1868, freethought advocate Chapman Cohen was born in Leicester, England, to Enoch Cohen, a confectioner, and his wife, Deborah (née Barnett). At the age of 21, he began a 50-year career as a popular and concise freethought writer and lecturer. When G.W. Foote died in 1915, Cohen succeeded him as president of the National Secular Society and editor of its publication The Freethinker.

Cohen was an efficient manager who brought security to the National Secular Society. He married happily and had a daughter, who died at age 29, and a son, who became a physician.

He gave up the NSS presidency in 1949 and handed The Freethinker over to F.A. Ridley in 1951. Cohen is considered the “last great Victorian freethinker.” (Victor E. Neuburg, The Encyclopedia of Unbelief) He wrote many articles and pamphlets, as well as Almost an Autobiography in 1940. (D. 1954)

“Gods are fragile things, they may be killed by a whiff of science or a dose of common sense. They thrive on servility and shrink before independence. They feed upon worship as kings do upon flattery. That is why the cry of gods at all times is ‘Worship us or we perish.’ ”

— Chapman Cohen, "The Devil," undated pamphlet

Annie Laurie Gaylor

On this date in 1955, Freedom From Religion Foundation co-president Annie Laurie Gaylor was born in Madison, Wisconsin, along with her twin, Ian Stuart Gaylor. With her mother Anne Gaylor, she co-founded FFRF in 1976 as a college student. Her 1977 complaint halted invocations and prayers at University of Wisconsin-Madison graduation ceremonies, ending a 122-year abuse. She earned a journalism degree from UW-Madison in 1980.

Gaylor’s book documenting bible sexism, Woe to the Women: The Bible Tells Me So, was first issued in 1981 and reissued in digital-only form in 2004 but is now out of print. In it Gaylor wrote: “The only true shield standing between women and the bible, that handbook for the subjugation of women, is a secular government. U.S. citizens must wake up to the threat of an encroaching theocracy, and shore up Thomas Jefferson’s ‘wall of separation between church and state.’ ”

She edited and published The Feminist Connection, a regional monthly, from 1980-84, then became editor of Freethought Today, the Foundation’s newspaper, in 1985. She wrote the first book exposing the clergy sexual abuse scandal, Betrayal of Trust: Clergy Abuse of Children (1988), and is editor of the first anthology of women freethinkers, Women Without Superstition: No Gods – No Masters (1997). She is married to Dan Barker, FFRF co-president, and they have one daughter.

“The only life that ought to concern any of us is leaving our planet and our descendants a secure and pleasant future.”

— Gaylor, quoted in Madison Magazine (2007)

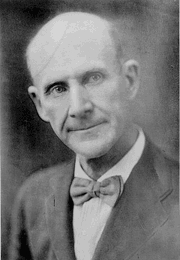

Eugene V. Debs

On this date in 1855, labor leader, reformer and socialist Eugene Victor Debs was born in Terre Haute, Ind. He was not baptized by his formerly Catholic mother. The family living room contained busts of Voltaire and Rousseau. When a teacher gave Debs a bible as an academic award, inscribing it “Read and obey,” Debs later recalled, “I never did either.” (New York Call interviews with David Karsner) He dropped out of high school at age 14 to work.

By 1870 he had become a fireman on the railroad, attending evening classes at a business college. His labor activism began in 1875. As president of the Occidental Literary Club of Terre Haute, Debs brought “the Great Agnostic” Col. Robert Ingersoll, whom he always revered despite political differences, Susan B. Anthony and other famous speakers to town. He was elected to the Indiana General Assembly as a Democrat in 1884 while continuing his labor activities. He married Kate Metzel in 1885. They never had children.

As editor of the Locomotive Fireman’s journal for many years, Debs routinely attacked the church, promoted women’s and racial equality and promoted justice for the poor. “If I were hungry and friendless today, I would rather take my chances with a saloon-keeper than with the average preacher,” Debs once said. (Cited in Eugene V. Debs: A Man Unafraid McAlister Coleman, 1930.) He saved his strongest denunciations for the Catholic Church for being an anti-democratic, authoritarian “political machine.”

Debs organized the first U.S. industrial union, the American Railway Union in Chicago in 1893. It conducted a successful 1894 strike for 18 days against the Great Northern Railway. Debs and leaders of the union were arrested that same year during the Pullman strike and were jailed for contempt of court for six months. Debs ran for president as a Socialist Party candidate in 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912 and 1920.

He was associate editor from 1907-12 of the Appeal to Reason, a popular weekly published by freethinker E. Haldeman-Julius in Girard, Kansas. In 1918 he was arrested for an anti-war speech in Canton, Ohio, and was sentenced under the wartime espionage law to 10 years in prison and loss of citizenship. While in prison he was nominated for president and conducted his last campaign, winning nearly a million votes.

President Warren G. Harding commuted Debs’ sentence and released him on Dec. 25, 1921. He was welcomed by 1,000 Terre Hauteans upon his return. His health broken by his imprisonment, he died at age 70 in a sanitarium. The Terre Haute home he built with his wife in 1890 is a National Historic Landmark of the National Park Service and a museum. (D. 1926)

“I left that church with rich and royal hatred of the priest as a person, and a loathing for the church as an institution, and I vowed that I would never go inside a church again.”

— "Talks with Debs in Terre Haute" by David Karsner (1922)

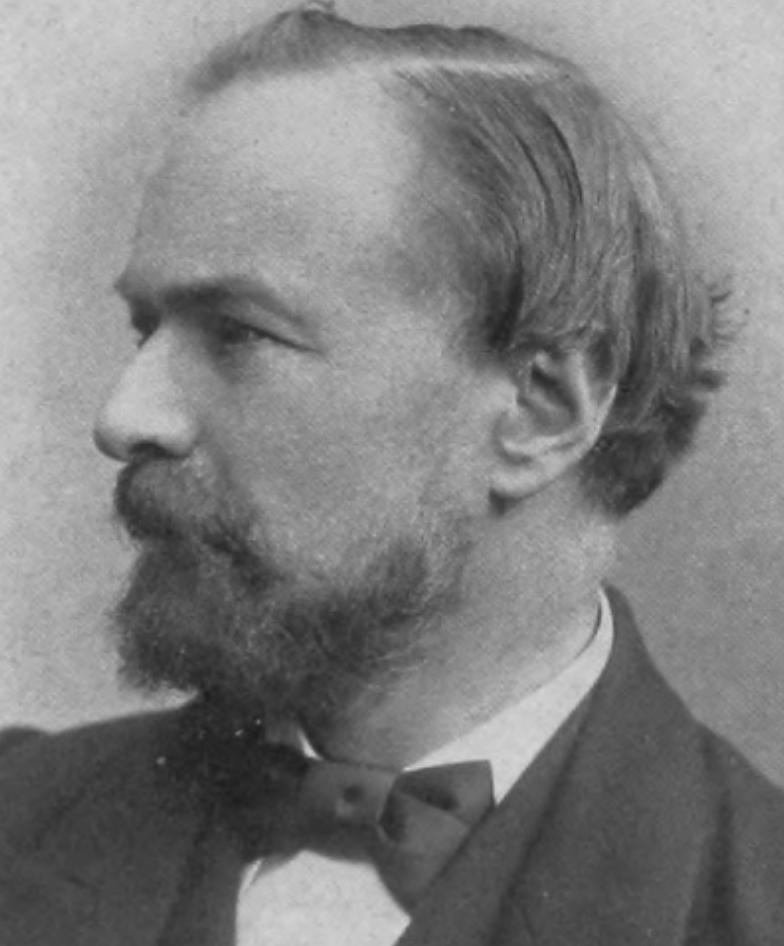

Francis Ellingwood Abbot

On this date in 1836, philosopher and theologian Francis Ellingwood Abbot was born into a family of Boston transcendentalists. Educated at Harvard and Meadville Theological School. He graduated from Harvard ranked number one in the class of 1859 and then married Katharine Fearing Loring. He became a Unitarian minister but by 1868 was forced to leave the pulpit in Dover, N.H., because his views were seen as too radical. New Hampshire’s highest court ruled in 1868 that he was “insufficiently Christian” to serve a splinter congregation in the building owned by the First Unitarian Society of Dover.

By now an avowed Darwinian, Abbot moved to Toledo, Ohio, to serve a Unitarian congregation but by 1872 it had dwindled in size to the point where members stopped paying his salary. Giving up on the pulpit, he founded the Free Religious Association and its journal The Index, a weekly paper “devoted to free religion” and “scientific theism.” He edited the paper until 1880, then founded another freethought journal, The Open Court. He taught at a boy’s school from 1881-92 in Cambridge, Mass.

Abbot wrote extensively. His books include Scientific Theism (1885), The Way Out of Agnosticism, or the Philosophy of Free Religion (1890) and The Syllogistic Philosophy, or Prolegomena to Science (two volumes, posthumously in 1906). In 1903, distraught on the 10th anniversary of his wife Katie’s death, Abbot died at age 66 on her grave in Beverly, Mass., after taking an overdose of sleeping pills. Theirs was a great love, author Brian Sullivan wrote in If Ever Two Were One: A Private Diary of Love Eternal (2005), a collection of Abbot’s correspondence and diary entries.

In 1894, a year after Katie’s death, he wrote, “[H]er soul was the violet of my home, fragrant with heaven’s own breezes, and lovely with a modest charm that kept me and keeps me her lover as in the days of yore.” (D. 1903)

“That great and growing evils render it a paramount patriotic duty on the part of American citizens, who comprehend the priceless value of pure Secular government, to take active measures for the immediate and absolute secularization of the state, and we earnestly urge them to organize without delay for this purpose.”

— Francis Ellingwood Abbot, from "Nine Demands of Liberalism," The Index (April 6, 1872)

Norm Allen

On this date in 1957, Norman Robert Allen Jr. was born in Pittsburgh to Fayevern (Robinson) and Norman Allen Sr., respectively a postal employee and a legal aide, and was the oldest of three sons. According to Allen, his mother encouraged him to keep an open but skeptical mind about religion. His father was a member of the Organization of Afro-American Unity headed by Malcolm X.

Allen attended the University of Pittsburgh before serving in the Air Force for four years, then enrolling at the State University of New York at Buffalo, majoring in English. He became a “full-fledged atheist” at age 31. (Mythinformed MKE, Oct. 14, 2016)

While working for the Council for Democratic and Secular Humanism in Buffalo, he started African Americans for Humanism (AAH) to explore the ideas and work of Black deists, humanists, agnostics, freethinkers, rationalists and atheists. He was AAH’s executive director from 1991 to 2010 and edited its quarterly the AAH Examiner. He also edited “African American Humanism: An Anthology” (1991) and “The Black Humanist Experience: An Alternative to Religion” (2003).

“I was originally motivated because I understand the many ways in which religion sends out contradictory messages, thereby contributing to widespread misery,” Allen said. “While acknowledging the good that many religions do, I believe it is necessary to unsparingly critique its many weaknesses.” (Council for Secular Humanism, Feb. 26, 2005)

Allen retired from organized secular humanism in 2013 after serving as secretary of the Institute for Science and Human Values and editing its journal The Human Prospect. He kept writing a regular column titled “Reasonings” for the institute and edited other writers’ work while traveling extensively to Africa, visiting over 30 nations to promote secularism.

In 1997, single and living in Buffalo, Allen told a newspaper that “atheism remains high atop the list of Topics to Avoid on the First Date,” comparing it to a felony conviction. Black atheists have a “harder row to hoe,” he said. “Religion permeates everything in our culture. You go to an NAACP meeting, and they’ll want to pray. You can go to a secular meeting, and they want to pray. When I’m in that coercive situation, I’m not going to stand for it. I don’t hesitate to walk out.” (Buffalo News, Dec. 14, 1997)

“Humanism is about solving our differences peacefully. We know of many religious wars, but organized humanists have not settled their differences with violence.”

— Allen statement to Humanists International on the United Nations International Day of Peace (Sept. 21, 2017)

Sir Leslie Stephen

On this date in 1832, former Anglican priest, author and political essayist Leslie Stephen was born in Kensington Gore, England. He was educated at Eton, King’s College and Cambridge, primarily studying mathematics. He was required to become an Anglican priest when he became a fellow of his college but was known for his athletics, not his sermons. He later told freethought historian Joseph McCabe that Cambridge was so liberal when he was there that if it was known a dinner party was open to heretics only, it was standing room only.

By 1862 he was refusing to participate in chapel services, saying he had not lost his faith but had discovered that he had never had any. He became editor of The Cornhill in 1871, a monthly journal earlier edited by William Makepeace Thackeray, whose daughter he had married. Stephen wrote freethought articles for Fraser’s and Fortnightly. In 1877 he wrote An Agnostic’s Apology. His writings include History of English Thought in the Eighteenth Century, two volumes (1876), Johnson (1878), Pope (1880), Swift (1882), Science of Ethics (1882) and The English Utilitarians, three volumes (1900).

Stephen also edited 26 volumes of the Dictionary of National Biography and was its first editor. In 1902 he was knighted and made a fellow of the British Academy. Today he is perhaps best known as the father of Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf and as the model for Woolf’s Mr. Ramsey in To the Lighthouse (1927). (D. 1904)

“I now believe in nothing, to put it shortly; but I do not the less believe in morality.”

— Stephen journal entry, Jan. 26, 1865. (Quote source: "2000 Years of Disbelief" by James A. Haught, 1996)

William Lloyd Garrison

On this date in 1805, anti-cleric and early abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison was born in Newburyport, Mass. Apprenticed to a newspaper at age 13, Garrison took up the abolition cudgels early. Sued for libel by the owner of a slave ship, he was convicted and sentenced to six months in prison, serving seven weeks. On the nation’s 50th anniversary, he wrote, “There is one theme which should be dwelt upon, till our whole country is free from the curse — SLAVERY.” He founded The Liberator in Boston in 1831. In its pages Garrison vowed, “I am in earnest, I will not equivocate, I will not excuse, I will not retreat a single inch, and I will be heard.”

He started the New England Anti-Slavery Society in 1832, then the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. He was especially critical of church complicity with slavery, not only in the South but in the North. Northern denominations refused to condemn slavery or sever ties with Southern slave-holding congregations.

The South Carolina city of Columbia offered a $1,500 reward for apprehension of anyone distributing The Liberator. The Georgia House of Representatives offered $5,000 for Garrison’s capture and trial. He narrowly evaded arrest there by fleeing to England. In 1835 he was dragged through the streets of Boston by a mob. The mayor rescued him by arresting him.

Garrison was an ardent “woman’s rights man” and early suffragist. He and other abolitionists and freethinkers attended a four-day bible convention “for the purpose of freely and fully canvassing the authority and influence of the Jewish and Christian Scriptures” in June 1853. More than 2,000 attended the event in Melodeon Hall in Hartford, Conn., a majority of them hostile, including 700 divinity students.

He was not a churchgoer or believer in orthodoxy, although he was deistic. The last issue of The Liberator was published in 1865. He remained active in progressive causes, especially suffrage. He died of kidney disease at age 73 in New York City. (D. 1879)

“The human mind is greater than any book. The mind sits in judgment on every book. If there be truth in the book, we take it; if error, we discard it. Why refer this to the Bible? In this country, the Bible has been used to support slavery and capital punishment; while in the old countries, it has been quoted to sustain all manner of tyranny and persecution. All reforms are anti-Bible.”

— Garrison remarks at the national woman's rights conference in Philadelphia, Oct. 18, 1854. "History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 1" (1887)

Queen Silver

On this date in 1910, “girl philosopher” Queen Silver was born in Portland, Oregon, where her mother, Grace Verne Silver, 21, a Socialist lecturer, was stranded during a tour. She never met her father or revealed his name, calling it “classified information.” At 10 days old she took the first of many railway journeys, going with her mother to Los Angeles, where they settled. Starting in 1917 they and her stepfather became extras in motion pictures to supplement their income. Silver was taught at home and was expected at an early age to be independent, to pay her own board and even cook her own meals.

She was reading Darwin at age 7, and at age 8 delivered a series of lectures in Los Angeles, an event noteworthy enough to be covered by the Los Angeles Record. At age 11, she publicly challenged William Jennings Bryan to a debate on evolution. Bryan declined. The Daily News in Inglewood carried a front-page article on June 29, 1925, reporting that “Inglewood’s famous girl philosopher, talker and writer” might attend the Scopes trial and pictured her holding a chimpanzee. She was unable to afford the trip but 1,000 of her pamphlets were distributed during the trial.

She was notorious enough that Cecil B. DeMille modeled the title character of his 1928 movie “The Godless Girl” after her. One synopsis: “Two teenagers, one an atheist and the other a Christian, fall in love at a brutal reform school.”

From 1923-34 she published “Queen Silver’s Magazine,” a 16-page periodical with a freethought angle and a national subscription. During the Depression, Silver took seasonal office work and, starting in 1936, became a junior typist clerk and withdrew for the most part from political involvement. Attending night school, she graduated from Los Angeles City College in the 1960s with an associate’s degree. She stayed in state civil service, working as a court reporter, and retired in 1972.

She helped to found the Los Angeles group that later became Atheists United, serving on its board and lecturing occasionally. She was a member of many humanist organizations, including FFRF. Wendy McElroy, a friend and admirer, published the biography Queen Silver: The Godless Girl in 2000, two years after Silver’s death at age 87. (D. 1998)

“In America, the church controls the State and Capital controls both Church and State. Capital finances religion and god sanctifies capital. The workingman is victimized by both god and gold. One destroys his brain and the other plunders his body.”

— From Silver's essay titled "God's Place in Capitalism" (1926)