novelists

Zora Neale Hurston

On this date in 1891, writer and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston was born in Eatonville, Fla., the first all-black community to be incorporated in the U.S. Her mother was a country schoolteacher and her father a Baptist preacher who became three-term mayor of Eatonville. “My head was full of misty fumes of doubt,” she would later write. “Neither could I understand the passionate declarations of love for a being that nobody could see. Your family, your puppy and the new bull-calf, yes. But a spirit away off who found fault with everybody all the time, that was more than I could fathom.”

She was farmed out to relatives when her mother died in 1904. By 14 she had left town to work as a maid for whites. As a live-in maid she enrolled at Morgan Academy in Baltimore. She attended Howard University intermittently from 1918-24 while working as a manicurist and maid for prominent blacks. She moved to New York City in 1925 with “$1.50, no job, no friends, and a lot of hope,” into the midst of the Harlem Renaissance.

Her short story “Spunk” (1925) brought her notice. Fannie Hurst, author of Imitation of Life (1933), gave her a job. Another white patroness arranged a scholarship for her at Barnard College. Hurston graduated in 1928 and did graduate study at Columbia, where her talents caught the eye of an anthropology professor, who suggested she incorporate anthropology into her writing.

A commission by a wealthy white patron to collect folklore stymied her career, since the contract barred Hurston from writing. In 1933 she wrote her best-known story, “The Gilded Six-Bits.” Her first novel, Jonah’s Gourd Vine, debuted in 1934, followed by Mules and Men (1937), Tell My Horse (1937) and the classic novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937). In all she wrote seven books plus her memoir Dust Tracks on a Road (1942).

Many of her short stories were published in magazines and anthologies. Hurston married three times but none of the marriages lasted. She was forced to take diverse “day jobs” to support her writing, from working as a drama instructor at North Carolina College for Negroes at Durham (1939), to working as a maid once again in 1950.

Writer Alice Walker revived interest in Hurston in the 1970s. A Hurston reader, I Love Myself When I am Laughing … and Then Again When I am Looking Mean and Impressive, was published in 1979. She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1994. The Complete Stories came out in 1995.

She died of a stroke and heart disease at age 69 in a home for the poor and was buried in an unmarked grave in Fort Pierce, Fla. (D. 1960)

“Prayer seems to me a cry of weakness, and an attempt to avoid, by trickery, the rules of the game as laid down. I do not choose to admit weakness. I accept the challenge of responsibility. Life, as it is, does not frighten me, since I have made my peace with the universe as I find it, and bow to its laws.”

— Hurston in her autobiography "Dust Tracks on a Road" (1942)

Simone de Beauvoir

On this date in 1908, French author and atheist Simone de Beauvoir was born in Paris to Georges Bertrand de Beauvoir, a legal secretary, and Françoise de Beauvoir (née Brasseur), a wealthy banker’s daughter and devout Catholic. A deeply religious child, she initially wanted to be a nun but at age 14 had a crisis of faith and concluded there was no God. She instead studied and taught philosophy and wrote prolifically.

Educated at the Sorbonne, de Beauvoir played a major role in the French Existentialist movement, along with close companion and atheist Jean-Paul Sartre. She is best-known for her monumental work The Second Sex (1949), in which she posited that society treats woman as “the other.” She also wrote popular novels and other nonfiction such as A Very Easy Death (1964). De Beauvoir championed freedom as the ultimate good.

She and Sartre were involved romantically from 1929 until his death in 1980. She never married or had children while engaging in a number of open relationships, including with women. Perhaps her most famous lover was American author Nelson Algren, whom she met in Chicago in 1947. She died of pneumonia at age 78 and is buried next to Sartre in Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris. (D. 1986)

PHOTO: Moshe Milner photo, Creative Commons 3.0

“Man enjoys the great advantage of having a God endorse the codes he writes; and since man exercises a sovereign authority over woman, it is especially fortunate that this authority has been vested in him by the Supreme Being. For the Jews, Mohammedans, and the Christians, among others, man is master by divine right; the fear of God, therefore, will repress any impulse toward revolt in the downtrodden female.”

— Simone de Beauvoir, "The Second Sex" (1949, translated and edited by H.M. Parshley, 1953)

A.A. Milne

On this date in 1882, classic children’s author Alan Alexander Milne, known as A.A. Milne, was born in England and brought up in London. With his brothers he attended his schoolteacher father’s school, Henley House. One of his influential teachers there was H.G. Wells. Attending Cambridge on a mathematics scholarship, Milne was given the gift of 1,000 pounds by his father upon graduation. He used it to move back to London and become a writer.

Milne freelanced for newspapers, joined the staff of Punch magazine and wrote a book that flopped, Lovers in London. In 1913 he married Dorothy “Daphne” de Sélincourt. In 1915 he volunteered in World War I and wrote his first play while serving. His only child, Christopher Robin, was born in 1920. In his 1974 book The Enchanted Places, Christopher wrote about being estranged from his parents and resenting what he came to see as his father’s exploitation of his childhood.

In his obituary in 1996, The Observer wrote: “Christopher Robin, a ‘sweet and decent’ man who overcame a childhood in which he was haunted by Pooh and taunted by peers, has left without saying his prayers – he was a dedicated atheist – aged 75.”

Milne’s When We Were Young was published in 1924, followed by Winnie the Pooh (1926), The House at Pooh Corner (1926) and Now We Are Six (1927). Milne subsequently wrote several plays, a detective novel and, in 1952, Year In, Year Out. (D. 1956)

PHOTO: Milne and Christopher Robin in 1926.

“The Old Testament is responsible for more atheism, agnosticism, disbelief — call it what you will — than any book ever written; it has emptied more churches than all the counter-attractions of cinema, motor bicycle and golf course.”

— A.A. Milne, cited in "2000 Years of Disbelief" by James A. Haught (1996)

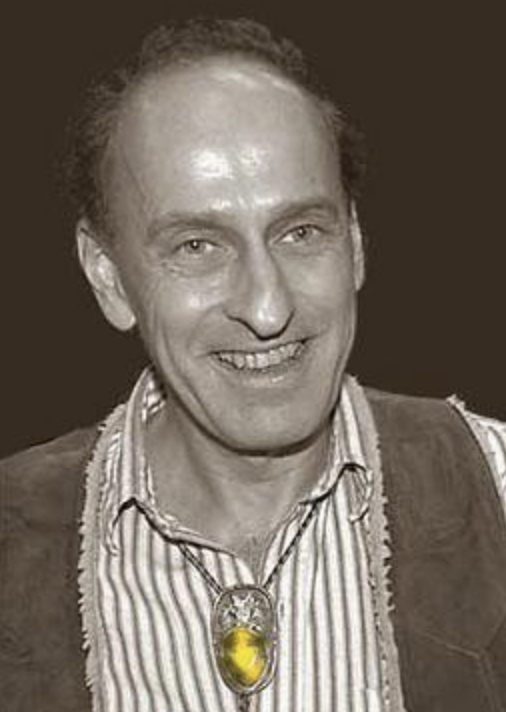

Julian Barnes

On this date in 1946, Julian Barnes was born in Leicester, England. He attended the City of London School, and graduated from Magdalen College in 1968 with a degree in modern languages. He became a reviewer and editor for the New Statesman and New Review in 1977 and worked as a television critic for the New Statesman from 1979-86. Barnes has published 18 novels (some under the pseudonym of Dan Kavanagh) as of this writing. The Sense of an Ending won the 2011 Booker Prize. The most recent are The Noise of Time (2016), The Only Story (2018) and The Man in the Red Coat (2019).

Barnes married literary agent Pat Kavanagh in 1979 and was widowed in 2011 after Kavanagh died of a brain tumor. He is the author of Nothing to be Frightened Of, a 2008 memoir focusing on death and mortality. “I don’t believe in God but I miss him,” Barnes proclaimed in the opening sentence. In a 2008 interview with Maclean’s magazine, he further explained, “I regard myself as a rationalist.”

PHOTO: Barnes in 2019. CC 4.0

“It is a bizarre thought that in this presidential cycle we could have had a woman in the White House, we might have a black man in the White House, but if either of them had said they were atheists neither of them would have had a hope in hell.”

— Barnes, interview with Maclean’s magazine (2008)

W. Somerset Maugham

On this date in 1874, William Somerset Maugham was born in Paris, where his father was an attorney with the British Embassy. He was orphaned by the time he was 10 after his father died of cancer and his mother of tuberculosis. He underwent medical training at St. Thomas Hospital in London, becoming a doctor in 1897. After publishing his first novel, Liza of Lambeth (1897), Maugham left his medical career to pursue writing. His literary skill and concise writing style helped him become an accomplished novelist, playwright and short-story writer.

He is most famous for writing the semi-autobiographical novel Of Human Bondage (1917). His other popular works include The Moon and Sixpence (1919), Cakes and Ale (1930), The Razor’s Edge (1944) and the short story “Rain” (1923). He married Syrie Wellcome following her divorce from Henry Wellcome in 1917. The marriage was unhappy and they divorced in 1928. They had one daughter, Mary Elizabeth, born in 1915. Many of Maugham’s significant relationships were with men. Frederick Gerald Haxton, his American secretary, was his lover and companion from 1914 until Haxton’s death in 1944.

Maugham was a nonbeliever who saw no need for religion. “I remain an agnostic, and the practical outcome of agnosticism is that you act as though God did not exist,” he wrote in his memoir The Summing Up (1938). In the notebook he kept from 1892-1949, he discussed his lack of religious beliefs more extensively: “I’m glad I don’t believe in God. When I look at the misery of the world and its bitterness I think that no belief can be more ignoble.” (A Writer’s Notebook, 1949.)

He continued in his notebook: “The evidence adduced to prove the truth of one religion is of very much the same sort as that adduced to prove the truth of another. I wonder if that does not make the Christian uneasy to reflect that if he had been in Morocco he would have been a Mahometan, if in Ceylon a Buddhist; and in that case Christianity would have seemed to him as absurd and obviously untrue as those religions seem to the Christian.” (D. 1965)

“I do not believe in God. I see no need of such idea. It is incredible to me that there should be an after-life. I find the notion of future punishment outrageous and of future reward extravagant. I am convinced that when I die, I shall cease entirely to live; I shall return to the earth I came from.”

— Maugham, "A Writer’s Notebook" (1949)

Rupert Hughes

On this day in 1872, writer Rupert Hughes was born in Lancaster, Mo. The family moved when he was 7 to Keokuk, Iowa. He earned a B.A. from Adelbert College in Cleveland and a master’s from Yale, 1893. He served in the Spanish-American War and in the infantry in World War I. His biographical subjects included George Washington and Samuel Gompers. More than 50 movies were written, directed or based on Hughes’ stories and novels. He founded and served for decades as president of the Hollywood Screenwriters Club.

Hughes, the uncle of future billionaire Howard Hughes, had his greatest Hollywood success in 1928 when he was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay for “The Patent Leather Kid.”

Raised in the Congregational Church, Hughes began to lose his faith in college after reading the entire bible. In 1924 he wrote Why I Quit Going to Church, published by the Freethought Press Association, a forthright and thorough analysis of what is wrong with religion. In it Hughes recounted the uproar provoked by a shortened version of the 158-page book in Cosmopolitan magazine about the harm of Christianity. He wrote, “I quit because I came to believe that what is preached in the churches is mainly untrue and unimportant, tiresome, hostile to genuine progress, and in general not worthwhile. … As for the God who is preached in the churches, I ceased to worship him because I could no longer believe in him or respect what is alleged of him.”

He married Agnes Wheeler Hedge in 1893. They had a daughter, Elspeth, before divorcing in 1903. He married actress Adelaide Bissell in 1908. She took her own life in 1923 while on tour in Haiphong, French Indochina. Hughes’ final marriage, to Elizabeth Patterson Dial, took place the next year. She died from an accidental overdose of sleeping pills in 1945. Elspeth died a few months later from cerebral apoplexy.

Hughes’ health began to fail in the late 1940s, leading to a stroke in 1953. He suffered a fatal heart attack while working at his desk on Sept. 9, 1956.

“I do not believe in a Santa Claus for grown-ups, and I do not believe that the vast number of church-people are doing the world any good by promulgating false ideas and false ideals.”

— Hughes, "Why I Quit Going to Church" (1924)

James A. Michener

On this date in 1907, writer James Albert Michener was born in New York City. An orphan, he spent his first few years at the Bucks County Poorhouse in Doylestown, Pa, until adopted by Edwin and Mabel Michener. As Quakers, they believed in social activism and took in several orphaned children. The family was extremely poor, moving often during Michener’s childhood. He felt that this gave him a strong sense of character, an acceptance of what life really looked like.

In an interview with the American Academy of Achievement, Michener stated, “I think the bottom line … is that if you get through a childhood like mine, it’s not all bad. … The sad part is, most of us don’t come out.” Michener credited his mother for reading to him every night. “I had all the Dickens and Thackeray and Charles Read and Sinkiewicz and the rest before I was the age of seven or eight.”

Michener realized at a young age that there was a bigger world to see and, when he was 14, started hitchhiking around the U.S. with only 35 cents in his pocket: “I went everywhere, and I did it on nothing.” This interest in the world lasted a lifetime. Michener received a scholarship to study at Swarthmore College, graduating with highest honors. He studied at St. Andrew’s University in Scotland, returned home to teach, and then went on to become assistant visiting professor of history at Harvard University.

At the onset of World War II, Michener joined the Navy and was stationed in the Pacific. In 1947 he wrote his first book, Tales of the South Pacific, relating some of his experiences in the Solomon Islands, for which he received a Pulitzer Prize. The story was subsequently turned into the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, “South Pacific,” which also received a Pulitzer.

Spending many years living abroad and writing, he thoroughly researched whichever culture he was living in before he started writing. Among his books are: The Bridges at Toko-Ri, Sayonara, The Source (about religion), Hawaii, Chesapeake, The Covenant, Space, Poland, Texas and Alaska. Michener was also active in public service, was a member of the Advisory Council to NASA and was cultural ambassador to various countries. He considered himself to be a humanist, and during the 1960s spoke out, amid the concerns raised regarding John F. Kennedy’s Catholicism: “I’ve fought to defend every civil right that has come under attack in my lifetime. … I’ve stood for absolute equality, and it would be ridiculous for a man like me to be against a Catholic for President.” (The Historian, 2001)

Michener won several honors and awards, among them the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian award. He was married three times — to Patti Koon from 1935 to 1948, when they divorced, to Vange Nord from 1948 to 1955, when they divorced, and to Mari Yoriko Sabusawa from 1955 to 1994, when she died.

He died of kidney disease at age 90 in Austin, Texas. (D. 1997)

PHOTO: Michener in 1991 at the 50th anniversary observance of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

“I am terrified of restrictive religious doctrine, having learned from history that when men who adhere to any form of it are in control, common men like me are in peril. I do not believe that pure reason can solve the perceptual problems unless it is modified by poetry and art and social vision. So I am a Humanist. And if you want to charge me with being the most virulent kind — a secular humanist — I accept the accusation.”

— Michener interview, Parade magazine (Nov. 24, 1991)

Alice Walker

On this date in 1944, novelist, poet and self-described “Earthling” Alice Malsenior Tallulah-Kate Walker was born in Eatonton, Georgia, the youngest of eight children in a sharecropping family. Blinded in one eye during a childhood accident, she went on to become valedictorian at her high school and attended both Spelman College and Sarah Lawrence College on scholarships. Walker graduated from Sarah Lawrence in 1965. She worked on voter registration drives in the 1960s and married fellow civil rights worker Melvyn Leventhal in 1967. They had a daughter, Rebecca, in 1970 and divorced in 1976.

Her first book of poetry was published in 1970. Walker edited I Love Myself When I Am Laughing and Then Again When I Am Looking Mean and Impressive: A Zora Neale Hurston Reader in 1979, introducing and popularizing Hurston to a new generation.

The Color Purple, Walker’s bestselling 1982 novel, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1983 and was turned into a popular movie by Steven Spielberg. Walker introduced the term “womanist” to the feminist movement to describe African-American feminism. Her books of essays include In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens: Womanist Prose (1983), Alice Walker Banned (1996) and Anything We Love Can Be Saved: A Writer’s Activism (1997).

Walker’s views on religion are expressed in “The Only Reason You Want to Go to Heaven Is That You Have Been Driven Out of Your Mind (Off Your Land and Out of Your Lover’s Arms): Clear Seeing Inherited Religion and Reclaiming the Pagan Self” (anthologized in Anything We Love Can Be Saved). Raised as a Methodist by devout parents, early in life she observed church hypocrisy, especially the silencing of the women who cleaned the church and kept it alive. “Life was so hard for my parents’ generation that the subject of heaven was never distant from their thoughts. … The truth was, we already lived in paradise but were worked too hard by the land-grabbers to enjoy it.”

In The Color Purple, the protagonist rebels against a God who [vernacular ahead] “act just like all the other mens I know. Trifling, forgitful and lowdown.” Walker, rebelling against the misogyny of Christian teachings and the imposition of a white religion upon the enslaved, wrote: “We have been beggars at the table of a religion that sanctioned our destruction.”

Walker added: “All people deserve to worship a God who also worships them. A God that made them, and likes them. That is why Nature, Mother Earth, is such a good choice. Never will Nature require that you cut off some part of your body to please It; never will Mother Earth find anything wrong with your natural way.”

“It is chilling to think that the same people who persecuted the wise women and men of Europe, its midwives and healers, then crossed the oceans to Africa and the Americas and tortured and enslaved, raped, impoverished, and eradicated the peaceful, Christ-like people they found. And that the blueprint from which they worked, and still work, was the Bible.”

— "Anything We Love Can Be Saved" (1997)

Octave Mirbeau

On this date in 1848, French playwright and novelist Octave Mirbeau was born in Paris. He was expelled from a Jesuit college at age 15. Mirbeau adopted strong anarchist views and a fondness for art and art criticism. He ghost-wrote at least 10 novels and many under his own name, including Le Calvaire (Calvary, 1886), Le Journal d’une femme de chambre (Diary of a Chambermaid, 1900) and Dingo (1913). In his 1888 novel, L’Abbé Jules, Mirbeau’s main character is a priest who rebels against Catholicism. The novel explores the repressive and abusive role religion plays in human life.

Sébastien Roch, published in 1890, recounts the sexual abuse of a 13-year-old boy by priests that results in the boy’s expulsion from school and the subsequent destruction of his life. Mirbeau’s plays included “Les Mauvais bergers” (The Bad Shepherds, 1897), the acclaimed “Les affaires sont les affaires” (Business is Business, 1904) and “Le Foyer” (Charity, 1908), a comedy accusing the Catholic Church of exploiting young girls. Mirbeau and French actress Alice Regnault wed in London in 1887. Mirbeau is buried in Paris. D. 1917.

“The universe appears to me like an immense, inexorable torture-garden. … Passions, greed, hatred, and lies; social institutions, justice, love, glory, heroism, and religion: these are its monstrous flowers and its hideous instruments of eternal human suffering.”

— from Mirbeau's novel "Le Jardin des supplices" (The Torture Garden), 1899

Anthony Burgess

On this date on 1917, Anthony Burgess (né John Anthony Burgess Wilson) was born in Manchester, England. His mother and sister died in the 1918 flu pandemic. The author of 50 books, he is best known for his novel A Clockwork Orange (1962), which was made into a movie directed by Stanley Kubrick in 1971. Burgess was also a translator, critic, composer, librettist and screenwriter. He wrote at least 65 musical compositions and preferred to be called “a musician who writes novels.”

He was educated at a Catholic college and graduated from Manchester University in 1940. He joined the British Army Education Corps, which entertained troops in Europe, and was stationed in Gibraltar. Burgess later said a World War II sexual assault by four American deserters on his first wife, Llewela Isherwood Jones, partly inspired his examination of violence in A Clockwork Orange.

He taught after the war and was a distinguished professor at the City College of New York, 1972-73.

“The ideal reader of my novels is a lapsed Catholic and failed musician, short-sighted, color-blind, auditorily biased, who has read the books that I have read,” he told The Paris Review in a 1973 interview. According to his 1993 New York Times obituary, he also once said, “I don’t think there’s a heaven, but there’s certainly a hell. Everything we’ve experienced on earth seems to point toward the permanence of pain.”

“I was brought up a Catholic, became an agnostic, flirted with Islam and now hold a position which may be termed Manichee. I believe the wrong God is temporarily ruling the world and that the true God has gone under. Thus I am a pessimist but believe the world has much solace to offer: love, food, music, the immense variety of race and language, literature and the pleasure of artistic creation.”

— Burgess, New York Times obituary (Nov. 26, 1993)

Victor Hugo

On this date in 1802, author Victor Marie Hugo was born in Besançon, France, the son of a Napoleonic officer. By 17 he had earned three prizes for poetry at Toulouse. King Louis XVIII awarded Hugo a royal pension after his Odes and Poetry appeared (1822). His first drama, “Cromwell,” was published in 1827.

After devoting nearly two decades to stage writing, Hugo turned to fiction. His novel, known in English as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, was published in 1831 and featured a villainous priest. It has been turned into several movies and dramatizations, including a Disney cartoon (which interestingly turned villain Claude Frollo into a layperson). Les Misérables was published in 1862 in 10 languages. The epic tale has spawned several movies and stage productions, including its Broadway debut in 1987.

Hugo was forced to flee to Belgium after Napoleon III’s coup d’etat in 1851. He eventually returned to France when the republic was proclaimed and was elected a senator in 1876. Although his religious views wavered over his long and tempestuous life, Hugo was anti-clerical, freedom-loving and generally considered to have been a rationalistic deist.

He married Adèle Foucher in 1822 and they had five children before her death in 1868. He suffered a mild stroke in 1878 and recovered. He died of pneumonia in Paris at age 83. (D. 1885)

“An intelligent hell would be better than a stupid paradise.”

— from Hugo's play "Ninety-three" (1881)

John Steinbeck

On this date in 1902, author John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. was born in Salinas, Calif. He studied marine biology at Stanford but did not graduate. His long list of humanistic novels includes the classics Of Mice and Men (1937) and The Grapes of Wrath (1939), which won a Pulitzer Prize. He also wrote Tortilla Flat (1935), The Red Pony (1937), Cannery Row (1945), East of Eden (1952) and The Winter of Our Discontent (1961), 33 books in all. He was awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize for Literature “for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humour and keen social perception.”

Asked to complete a routine medical questionnaire for his new doctor, Steinbeck did so and added a letter dated March 5, 1964: “I shall probably not change my habits very much unless incapacity forces it. I don’t think I am unique in this. Now finally, I am not religious so that I have no apprehension of a hereafter, either a hope of reward or a fear of punishment. It is not a matter of belief. It is what I feel to be true from my experience, observation and simple tissue feeling.” (Steinbeck: A Life in Letters, ed. Elaine Steinbeck, 1975)

He married Carol Henning in 1930, divorced in 1943; Gwyn Conger in 1943, divorced in 1948; and Elaine Anderson Scott in 1950, together until his death in in New York City at age 66 from congestive heart failure. He had two sons with his second wife. (D. 1968)

“Literature was not promulgated by a pale and emasculated critical priesthood singing their litanies in empty churches — nor is it a game for the cloistered elect, the tinhorn mendicants of low calorie despair.”

— Steinbeck, Nobel Prize acceptance speech (1962)

Daniel Handler

On this date in 1970, Daniel Handler was born in San Francisco. His father was a Jewish refugee from Germany. Handler graduated in 1992 from Wesleyan University, where he met graphic artist Lisa Brown, his future wife. His first novel, The Basic Eight, was published in 1999. Handler is best known for his writing under the pen name Lemony Snicket, most notably the 13-volume A Series of Unfortunate Events. In these children’s books, Snicket is slowly revealed to be not only a pen name but an important character in the fictional world Handler created.

The three protagonists are orphans who live in a fictional world where they must continually battle against adversity and the efforts of various villains to steal their fortune. The first book, The Bad Beginning, was published in 1999, and the last, The End, in 2006. During this time, Handler made many personal appearances and gave several interviews as Lemony Snicket’s personal assistant, claiming that Mr. Snicket had been unable to appear at the last minute.

Since the conclusion of the series, Handler has written picture books and short stories under the Snicket name. He also continues to write for adults under his own name, including the novels Watch Your Mouth (2000) and Why We Broke Up (2011). Handler has also worked as a screenwriter and was involved in the production of the 2004 film adaptation of the beginning of the series.

Handler describes himself as a secular humanist. He drew on his Jewish heritage in the winter holiday book The Latke Who Couldn’t Stop Screaming (2007).

PHOTO: Handler in 2009 at a book signing; Aaron Gustafson photo under CC 2.0.

“The [‘Series of Unfortunate Events’] books have drawn the ire and praise of fundamentalist Christians, some of whom believe the books to be Christian allegories and some of whom believe them to be long insults against Christianity. The thing is, the books are really neither.”

— Handler interview on CNN.com (Oct. 5, 2006)

John Fowles

On this date in 1926, novelist John Robert Fowles was born in Leigh-on-Sea, Essex, outside London. After serving two years as a lieutenant in the Royal Marines, Fowles went to Oxford, where he graduated in 1950 with a degree in French. As a college student, he admired the French existentialists, particularly Camus and Sartre. Fowles lectured in Poitiers, France, then spent two years on the Greek island Spetses, teaching college English. There he met his future wife Elizabeth Christy, then married to a fellow teacher. From 1954-63, he taught English at St. Godric’s College, London.

The phenomenal success of his first published novel, The Collector (1963), permitted him the luxury of becoming a fulltime writer. The Magus, set on a Greek island with an English protagonist who teaches at a school, was published in 1965 and revised in 1977. (A 1968 film based on it was panned by critics, with Woody Allen quoted as saying, “If I had to live my life again, I’d do everything the same, except that I wouldn’t see ‘The Magus.’ “) These novels were followed by The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1969), Daniel Martin (1977), Mantissa (1982) and A Maggot (1985).

Fowles also wrote poetry and nonfiction. His book of essays, Wormholes, came out in 1998. The vivid The Collector, a disturbing tale of a young butterfly collector who decides to kidnap a woman he has a crush on, was made into a memorable film in 1965 starring Terrance Stamp. The French Lieutenant’s Woman, Fowles’ most commercial success, inspired a 1981 movie of the same name, starring Meryl Streep.

Fowles’ semi-autobiographical protagonist in Daniel Martin is described as an atheist. According to the Spring 1996 volume of Twentieth Century Literature, which was devoted to Fowles, he “repeatedly defined himself as an atheist.” In a New York Times interview with James R. Baker (“Art of Fiction”), Fowles said: “I stay an atheist, a totally unreligious man, with a deep, deep conviction that there is no afterlife.” (D. 2005)

“Being an atheist is a matter not of moral choice, but of human obligation.”

— Fowles, quoted in The New York Times Book Review (May 31, 1998)

Milan Kundera

On this date in 1929, novelist Milan Kundera was born in Brno, Czechoslovaki (now the Czech Republic). He grew up in a cultured, middle-class family and graduated from the Faculty of Arts, Charles University, in 1952. Kundera was expelled from the Communist Party in 1950, then readmitted in 1956 and expelled again in 1970. He became an assistant, then a professor, at the Film Faculty at Prague’s Academy of Performing Arts. His first book was published in 1953 and he continued publishing poetry and short stories until his novel The Joke was published in 1967.

During the 1968 Soviet invasion, Kundera became a leader of the resistance, lost his teaching post and saw his books banned. He lost his citizenship in 1979 for writing The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. Since 1975 he has lived in France with his wife Vera and became a French citizen in 1981. His other books include Life is Elsewhere (1969), The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1986), The Art of the Novel (1988, in which he discusses his lack of religion), Slowness (1994) and Identity (1998).

Unbearable Lightness was turned into a movie in 1988 starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Juliette Binoche. Kundera cites Diderot as one of his literary icons.

“I was never a believer, but after seeing Czech Catholics persecuted during the Stalinist terror, I felt the deepest solidarity with them. What separated us, the belief in God, was secondary to what united us. In Prague, they hanged the Socialists and the priests. Thus a fraternity of the hanged was born.”

— Kundera, New York Times interview (May 19, 1985)

Émile Zola

On this date in 1840, Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola was born in Paris. The novelist pioneered naturalistic writing, believing ugly problems could not be solved as long as they stayed hidden. As a struggling young writer, Zola supported himself as a clerk. Legend has it he sometimes resorted to trapping birds on his windowsill in order to eat. Zola also moonlighted as a political reporter and critic. He was fired from a publishing house after an early autobiographical novel created notoriety.

His breakthrough novel was Therese Raquin (1867). By the time his book L’Assammoir (“The Drunkard,” 1878) appeared, Zola was France’s most famous writer, yet he was barred his entire life from the Academy. His book Germinal (1885), about conditions in a coal mine leading to a strike, was denounced by the rightwing. Nana (1880) examined sexual exploitation.

Zola’s most enduring work is his open letter “J’Accuse,” about the Dreyfus case. He campaigned with Clemenceau to free the the French Jewish army officer falsely accused of spying. Zola was sentenced to imprisonment for writing “J’Accuse” in 1898, escaping to England until he could safely return after Dreyfus’ name had been cleared. Zola, who was baptized Catholic, was a notable critic of the Catholic Church (and vice versa). The church particularly condemned his books Lourdes, Rome, and Paris (1894-98). He was an honorary associate of the British Press Association. (D. 1902)

PHOTO: Zola, circa 1865.

“Given Émile Zola’s reputation as an agnostic and a radical thinker, he has often been avoided by scholars with a religious background.”

— Anthony Evenhuis, "Messiah Or Antichrist?: A Study of the Messianic Myth in the Work of Zola" (1998)

Arthur Hailey

On this date in 1920, writer Arthur Hailey was born in Bedfordshire, England. In 1939 he joined the Royal Air Force as a pilot and served until 1947, when he emigrated to Canada. His career as a writer began in 1955 when he imagined what would happen if the pilot and co-pilot both became ill and if he, as a former fighter pilot, would be able to fly the plane. His teleplay, “Flight Into Danger,” produced by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, later morphed into the successful novel, Airport (1968), which was spoofed in the 1980 Leslie Nielsen movie “Airplane!”

After working as a television writer, Hailey began to write novels, some based on his TV scripts. His books were aimed at a popular audience and many were best-sellers. Hailey is often considered to be one of the pioneers of the “disaster fiction” genre and, by extension, the “disaster movie.” Many of the novels are set in institutions the public must interact with — like airports and hotels — but are unaware of their inner workings.

Hailey’s last novel, Detective (1998), is a mystery told from the perspective of a Miami homicide detective. This detective also happens to be a former Catholic priest who has lost his religion; the work deals with themes of religion and questions the Catholic Church. Hailey said his aim in writing the book was to share his own thoughts about religion without making it “a lecture.”

He married Joan Fishwick in 1944 and was divorced in 1950, then was married to Sheila Dunlop from 1951 until his death at age 84. He had six children. (D. 2004)

“”But quite suddenly, as I was reciting the Creed in a church in Cyprus, where we were stationed, I found myself saying ‘I don’t believe this any more.’ I lost my faith and became an agnostic.”

— Hailey, quoted in The Independent (Nov. 27, 2004)

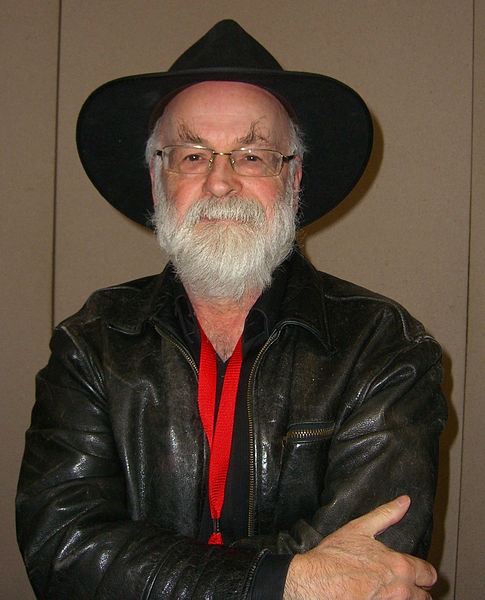

Sir Terence (Terry) Pratchett

On this date in 1948, Terence David John Pratchett was born in Buckinghamshire, England. He enjoyed reading, especially science fiction, fantasy, myth and ancient history. He has said that from a young age he was skeptical about Christianity and came to the conclusion that there was no God. He won many awards, including the Carnegie Medal for The Amazing Maurice and Educated Rodents (2001), and was knighted in 2009 for his services to literature. Several of his books have been adapted as movies for television. Pratchett’s first novel, Carpet People, a children’s fantasy, was published in 1971.

Pratchett is best known for his “Discworld” novels, a fantasy series tied together not by characters or plot but by the setting of the Discworld, a flat world sitting on the backs of four elephants standing on the back of a giant turtle swimming through space. The first book in this series, The Color of Magic, a fantasy adventure starring a hapless wizard parodying many conventions of the genre, was published in 1983, and the 38th, I Shall Wear Midnight, a coming-of-age story featuring a strong young witch battling prejudice, was published in 2010. The Discworld, like many fantasy worlds, features gods who occasionally interfere directly in events or feature as characters in some way.

Throughout his work, Pratchett questions religion in many different ways, pointing out religious hypocrisy while at the same time illustrating how different the world would be if God, or any gods, were real. The 1992 Discworld novel Small Gods shows the god Om visiting his worshipers, and being deeply dissatisfied with the direction in which his church has gone. Good Omens (1990), co-written with fellow British fantasy author Neil Gaiman, deals with Christian mythology and the biblical book of Revelation.

It begins with an angel and a demon conversing outside the Garden of Eden and questioning God’s motives regarding the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. It ends with the 10-year-old anti-Christ, Adam, contemplating the raid of a neighbor’s orchard and thinking, “There never was an apple … that wasn’t worth the trouble you got into for eating it.” Pratchett said, “I read the Old Testament all the way through when I was about 13 and was horrified.” (UK Daily Mail, June 21, 2008)

In 2007, Pratchett was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s, but continued to write and publish new books, albeit at a slower pace. He made many public statements in support of the right to die and talked openly about his Alzheimer’s experience, including his wish to take his own life before his disease was critical. He died of Alzheimer’s complications at age 66. (D. 2015)

PHOTO: by © Luigi Novi / Wikimedia Commons under CC 3.0.

“There is a rumor going around that I have found God. I think this is unlikely because I have enough difficulty finding my keys, and there is empirical evidence that they exist.”

— Pratchett, The Daily Mail (June 21, 2008)

Roger Zelazny

On this date in 1937, Roger Zelazny was born in Euclid, Ohio. Zelazny received his B.A. in English literature from Western Reserve University. He went on to study Elizabethan and Jacobean drama at Columbia, where he graduated with a master’s in English and comparative literature. Zelazny’s writing career blossomed in the early 1960s. All of his shorter works have been published in a six-volume set (The Collected Stories of Roger Zelazny) by NESFA Press (2009). The set includes an integrated biography (… And Call Me Roger) by Christopher Kovacs.

Zelazny was also famous for his novels. Perhaps the best known were the two Amber series, comprised of five novels each. Though death cut short his career, awards for his writing were impressive. They included three Nebulas (out of 14 Nebula nominations), six Hugos (out of 14 Hugo nominations), two Locus Awards, two Seiun awards, and one Prix Tour-Apollo award.

Zelazny had a fascination with mysticism and was an expert on religion and mythology. In fact, he frequently employed myth as a basis for his stories, including the seasonal death and resurrection themes that often characterized gods. Not prone to sharing details of his personal life, people speculated about what Zelazny believed in and if it was reflected in his writings.

Zelazny was married twice, first to Sharon Steberl in 1964 (divorced, no children), and then to Judith Alene Callahan in 1966, with whom he had two sons, Devin and Trent. He died at age 58 of kidney failure secondary to colorectal cancer. (D. 1995)

“I did have a strong Catholic background, but I am not a Catholic. Somewhere in the past, I believe I answered in the affirmative once for strange and complicated reasons. But I am not a member of any organized religion. If you mention my Catholic background, I hope you also mention that I became a retired Catholic at age 16. I do not consider myself a Christian.”

— "... And Call Me Roger: The Literary Life of Roger Zelazny" by Christopher S. Kovacs (2009)

Honoré de Balzac

On this date in 1799, Honoré de Balzac was born in France. Educated by the Oratorian priests at Vendome College, Balzac became a lawyer’s clerk at his parents’ insistence. When he turned to writing, his parents reduced his allowance. Balzac worked in legendary privation for the next decade, honing his skill with his first unsuccessful novels. Success came in 1830, when he produced the first part of his 47-volume La Comédie humaine.

The prolific writer also wrote 24 unrelated novels. Skepticism pervades Balzac’s many masterpieces, including Pere Goriot and Cousin Bette. He did not marry until later in life but died at age 51, five months after marrying his longtime love Ewelina Hańska. (D. 1850)

“I am not orthodox, and I do not believe in the Roman Church. I think that if there is a scheme worthy of our kind it is that of human transformations causing the human being to advance toward unknown zones. That is the law of creations inferior to ourselves; it ought to be the law of superior creations. Swedenborgianism, which is only a repetition in the Christian sense of ancient ideas, is my religion, with the addition which I wish to make to it of the incomprehensibility of God.”

— Letter to Ewelina Hańska, his future wife (May 31, 1837)

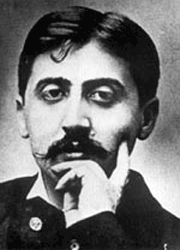

Marcel Proust

On this date in 1871, Marcel Proust, the freethinking pioneer of the moderan novel, was born in Auteuil, France, near Paris. His father, a Christian, was a prominent physician and his mother’s family was Jewish. Although plagued by chronic asthma and well-publicized neuroses, he completed his one-year stint of military service and studied law. He met Anatole France, who became his patron for a time.

Like many other French writers of his day, Proust was active in opposing the prosecution of Alfred Dreyfus. When his first book of short stories, essays and poetry was not a success, he turned to translating the works of art historian John Ruskin. He then devoted much of his remaining life to Remembrance of Things Past, his seven-volume masterpiece.

Proust’s sexuality and relationships with men are often discussed by his biographers. In poor health for several years and afflicted by asthma, he died of pneumonia and a pulmonary abscess at age 51 in his apartment in Paris. (D. 1922)

“[Proust] was baptized (on August 5, 1871, at the church of Saint-Louis d’Antin) and later confirmed as a Catholic, but he never practised that faith and as an adult could best be described as a mystical atheist, someone imbued with spirituality who nonetheless did not believe in a personal God, much less in a savior.”

— "Marcel Proust: A Life" by Edmund White (2009)

Taslima Nasrin

On this date in 1962, freethinker, atheist and feminist Taslima Nasrin was born in Mymensing, Bangladesh, to a Sufi physician and a devoutly religious mother. Nasrin later became the target of a series of fatwas, or religious sanctions, condemning her to death for blasphemy.

“I came to suspect that the Quran was not written by Allah but, rather, by some selfish, greedy man who wanted only his own comfort,” Nasrin explained in her speech accepting a Freethought Heroine Award at the 25th annual FFRF convention in 2002. “So I stopped believing in Islam. When I studied other religions, I found they, too, oppressed women.” She has often stated, “Religion is the great oppressor, and should be abolished.”

Nasrin earned an MBBS degree in 1984 and worked in gynecology and anesthesiology departments in medical colleges and universities. Her books of poetry began being published in the late 1980s, then she started writing popular columns on women’s rights in newspapers and magazines, which were collected in book form. In 1992, she received the prestigious Indian literary award “Ananda” for her book of essays. Nasrin reports that Islamic fundamentalists started campaigns against her by 1990, with demonstrations escalating over the next few years, including having her books burned at the national book fair.

When the novella “Shame” came out in 1993, about the plight of Hindus under Muslim order, it was banned, she was attacked at the national book fair, the first of three fatwa was issued, and a bounty on her head was offered. The Bangladeshi government brought criminal charges against her for defaming the Muslim faith the following year. Thousands in Bangladesh demonstrated regularly, sometimes daily, demanding her death. After a terrifying two months in hiding, and fearing the fate of Hypatia, Nasrin fled Bangladesh, seeking refuge in Sweden.

In a 1994 interview with The New Yorker, she said, “I want a modern, civilized law where women are given equal rights. I want no religious law that discriminates, none, period — no Hindu law, no Christian law, no Islamic law. Why should a man be entitled to have four wives? Why should a son get two-thirds of his parents’ property when a daughter can inherit only a third?”

Nasrin, a “woman without a country,” has also lived in France, the U.S. and Germany, living, for the most part, in India.

Among the dozens of awards and honorary doctorates she has received is the Sakharov Prize (1994). In addition to receiving FFRF’s 2002 Freethought Heroine Award, she was the recipient in 2015 of its Emperor Has No Clothes Award and said, “Islam is not compatible with human rights, women’s rights, freedom of expression and democracy.” She has continued to lecture, speak out and write, including a multi-book autobiography.

PHOTO: Nasrin at FFRF’s national convention in 2015; Ingrid Laas photo.

“There has always been a marked conflict between religion and science, and every time science emerges as the winner, as science bases itself on facts, not faith. It supports what is tested and is true and truth cannot be hidden by lies for a very long time. To abolish all kinds of hypocrisy from my country, we need more atheists to speak the truth.”

— Nasrin, accepting the Emperor Has No Clothes award in 2015

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

On this date in 1749, Germany’s most famous poet, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, was born in Frankfurt am Main, to a comfortable bourgeois family. He began studying law at Leipzig University at the age of 16 and practiced law briefly before devoting most of his life to writing poetry, plays and novels. In 1773, Goethe wrote the powerful poem “Prometheus,” which urged human beings to believe in themselves more than in gods.

His first novel was The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774), a semi-autobiographical tragedy about a doomed love affair. A line from that novel: “We are so constituted that we believe the most incredible things: and, once they are engraved upon the memory, woe to him who would endeavor to erase them.” In his 1797 Hermann and Dorothea, Goethe observed: “The happy do not believe in miracles.” Goethe typified the Sturm und Drang romantic movement, celebrating the individual. The Grand Duke of Weimar appointed him an administrator in 1775, where, according to some historians, Goethe turned Weimar into “the Athens of Germany.”

Goethe was keenly interested in the natural sciences and in his studies discovered the human intermaxillary bone (also known as the Goethe bone, adjacent to the incisors). After a sojourn in Italy from 1786 to 1788 he returned to his art. Starting a journal inspired by Christopher Marlowe‘s play “Faust,” Goethe wrote part 1 of his most famous play, published in 1808. Part 2 was published in 1832. From Part 1, Scene 9: “The church alone beyond all question / Has for ill-gotten gains the right digestion.”

Goethe’s religious beliefs were complicated and changed at various periods in his long life. He was raised Lutheran and was quite devout when young but grew to have problems with Christianity’s dogma, hierarchy and superstitious aspects. He revered Spinoza, whom Nietzsche often paired with Goethe. His later spiritual perspective incorporated pantheism (heavily influenced by Spinoza), humanism and elements of Western esotericism, as seen most vividly in part 2 of “Faust.”

“Goethe was a freethinker who believed that one could be inwardly Christian without following any of the Christian churches, many of whose central teachings he firmly opposed, sharply distinguishing between Christ and the tenets of Christian theology, and criticizing its history as a ‘mishmash of fallacy and violence,’ ” states the 1982 German publication Goethe’s Poems in Chronological Order.

He died at age 82 of apparent heart failure in Weimar. Of his five children, only a son, August, survived into adulthood. (D. 1832)

In the wilderness a holy man

To his surprise met a servant of Pan,

A goat-footed faun, who spoke with grace;

“Lord, pray for me and for my race,

That we in heaven find a place:

We thirst for God’s eternal bliss.”

The holy man made answer to this:

“How can I grant thy bold petition,

For thou canst hardly gain admission

In heaven yonder where angels salute:

For lo! thou hast a cloven foot.”

Undaunted the wild man made the plea

“Why should my hoof offensive be?

I’ve seen great numbers that went straight

With asses’ heads through heaven’s gate.”— Goethe poking fun at pietists claiming his cloven-hoofed paganism would bar him from heaven. "Goethe: With Special Consideration of His Philosophy" by Paul Carus (1915)

Edgar Rice Burroughs

On this date in 1875, Edgar Rice Burroughs was born in Chicago. He graduated from the Michigan Military Academy in 1895 and enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1896 but was discharged after only a year due to a heart condition. He became a full-time writer of pulp fiction in 1912, the year he published his story “Tarzan of the Apes” in The All-Story Magazine. The story was an overwhelming success and Burroughs went on to publish 26 Tarzan novels, which became famous worldwide.

The novels detail the life of Tarzan, an Englishman who was raised by apes in the African jungle. The books have been made into over 50 different movies, beginning with the silent film “Tarzan of the Apes” in 1918, which was one of the first films to make over a million dollars. Tarzan novels have also been adapted into a 1932 radio drama, the Broadway play “Tarzan of the Apes” (1921) and Broadway musical “Tarzan” (2006), the Disney animated movie “Tarzan” (1999) and five television series.

Respect for his Tarzan stories has, despite their early popularity, diminished due to growing awareness of their implicit racist and imperialist prejudices that were rampant and rarely challenged in Western culture when he wrote them. Revised variations of the Tarzan theme in multiple genres since then have tackled the difficult task of reducing or removing the prejudices inherent in the core of the Tarzan concept, with varying degrees of success.

Burroughs wrote 50 other books, many of which were science fiction, including A Princess of Mars (1912), At the Earth’s Core (1914) and The Cave Girl (1925). He married Emma Hulbert in 1900 and had three children: Joan, John and Hulbert. They lived in Tarzana, Calif., which Burroughs founded in 1928.

On July 6, 1925, Burroughs published an article supporting evolution. He wrote, “If we are not religious, then we must accept evolution as an obvious fact. If we are religious, then we must either accept the theory of evolution or admit that there is a power greater than that of God.” Burroughs’ novel The Gods of Mars (1918) contained freethought themes, describing a deeply religious society where religion was a myth perpetuated as a way to cover up murder.

He died of a heart attack at age 74 at home in Encino, Calif. He was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 2003. (D. 1950)

“Men who had not progressed as far as we have tried to interpret [evolution] some two thousand years ago. It is not strange that they made mistakes. They were ignorant and superstitious.”

— Edgar Rice Burroughs, New York America, July 6, 1925 (quoted in "Tarzan Forever" by John Taliaferro, 1999)

Robert M. Pirsig

On this date in 1928, Robert M. Pirsig was born in Minneapolis. He was tested with an IQ of 170 when he was only 9 years old. He enrolled in the University of Minnesota when he was 15, but left to join the army in 1946. Pirsig returned to the university and graduated with a degree in philosophy in 1950, as well as studying philosophy at Banaras Hindu University in India and earning his M.A. in journalism from the University of Minnesota in 1958.

He later became a professor of English rhetoric and composition at the University of Montana, but stopped teaching after he was briefly diagnosed with schizophrenia and depression. He appeared to recover after some institutional care.

In 1974, Pirsig wrote the wildly popular philosophical book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values, in which he detailed a motorcycle trip he took with his son, Chris, while illustrating philosophical ideas. In the book, Pirsig wrote about his theory, “the metaphysics of quality,” which is still widely discussed today.

He married his first wife, Nancy Ann James, in 1954, and they had two sons: Chris, who died in 1979, and Ted. Pirsig married Wendy Kimball in 1978 and the two had a daughter, Nell, born in 1980.

In Pirsig’s novel, Lila: An Inquiry Into Morals (1991), Pirsig wrote, “A person isn’t considered insane if there are a number of people who believe the same way. Insanity isn’t supposed to be a communicable disease. If one other person starts to believe him, maybe two or three, then it’s a religion.” He was quoted in Richard Dawkins’ 2006 book, The God Delusion, as having said more succinctly, “When one person suffers from a delusion, it is called insanity. When many people suffer from a delusion it is called Religion.” D. 2017.

“Religious mysticism is intellectual garbage. It’s a vestige of the old superstitious Dark Ages when nobody knew anything and the whole world was sinking deeper and deeper into filth and disease and poverty and ignorance. It is one of those delusions that isn’t called insane only because there are so many people involved.”

— Pirsig, "Lila: An Inquiry Into Morals" (1991)

Malcolm Bradbury

On this date in 1932, Malcolm Stanley Bradbury was born in Sheffield, England. He earned a degree in English from University College at Leicester in 1953, an M.A. in English literature from Queen Mary College in 1955 and a Ph.D. in American studies at the University of Manchester in 1962. He finished his first novel, Eating People is Wrong, while recovering from major heart surgery. The book was published in 1958. Bradbury later published five more novels, including The History Man (1975), which was made into a BBC television series in 1981.

Bradbury helped found the influential Creative Writing M.A. course at the University of East Anglia in 1970 — Ian McEwan was the first student — and was a professor of American studies. He wrote over 50 scripts for television shows, screenplays and radio dramas, including the crime series “A Touch of Frost” (1992–99) and television series “Anything More Would Be Greedy” (1989).

Bradbury married Elizabeth Salt in 1959 and they had two children, Dominic and Matthew. He was knighted in 1991 for his services to literature. He suffered from a cardiac condition and died of pneumonia at age 68. (D. 2000)

“Malcolm is an agnostic and didn’t want to be married in church.”

— Bradbury’s wife Elizabeth, interview with The Independent (April 9, 1995)

James Fenimore Cooper

On this date in 1789, James Cooper (later known as James Fenimore Cooper) was born in Burlington, N.J. He briefly attended Yale College and in 1808 joined the U.S. Navy. Cooper is best known for writing The Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757 (1826), an extremely popular novel focusing on the involvement of the Mohicans, a Native American tribe, in the French and Indian War. The novel was made into films in 1920, 1932, 1936, 1963 and 1992, as well as TV series in 1977, 1975 and 1987. It was also adapted into a BBC radio series in 1995 and an opera in 1976.

The Last of the Mohicans was the second book in Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales series, which included four other novels. Cooper wrote over 50 more books in various genres, including The Pilot: A Tale of the Sea (1824), the nonfiction The Chronicles of Cooperstown (1838) and American war novel The Spy (1821). He married Susan Augusta DeLancey in 1811 and the couple had seven children. (D. 1851)

“Ignorance and superstition ever bear a close and mathematical relation to each other.”

— Cooper, quoted in "Closures: Webster’s Quotations, Facts and Phrases" (2008)

Graham Greene

On this date in 1904, Graham Greene was born in Hertfordshire, England. He graduated with a B.A. in history from Balliol College in 1925, where he worked as an editor for The Oxford Outlook. After graduating, he became an editor for The Times of London. He left in 1930 to become a film critic for The Spectator.

Greene’s 24 novels included The Power and the Glory (1940), The Heart of the Matter (1948) and The Quiet American (1956). He gained inspiration for them partially from his travels in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Mexico, Vietnam and other countries. He also published short stories and screenplays, including “The Third Man” (1949). Greene worked for the British Secret Intelligence Service during World War II.

Greene was an agnostic who converted to Catholicism in 1926 after becoming engaged to Vivien Dayrell-Browning. In his autobiography A Sort of Life (1971), he wrote that his conversion was difficult: “I disbelieved in God. If I were ever to be convinced in even the remote possibility of a supreme, omnipotent and omniscient power, I realized that nothing afterwards could seem impossible. It was on the ground of dogmatic atheism that I fought and fought hard.”

After his conversion, many of his novels and stories included Catholic themes. However, in a 1987 interview, Greene said, “I’ve always found it difficult to believe in God. I suppose I’d now call myself a Catholic atheist” (quoted in The New York Times, 1991). Robin Turton, a politician and friend of Greene, said: “I think in my life I’ve never heard atheism put forward better than by Graham.” (Graham Green: Fictions, Faith and Authorship, 2010.) (D. 1991)

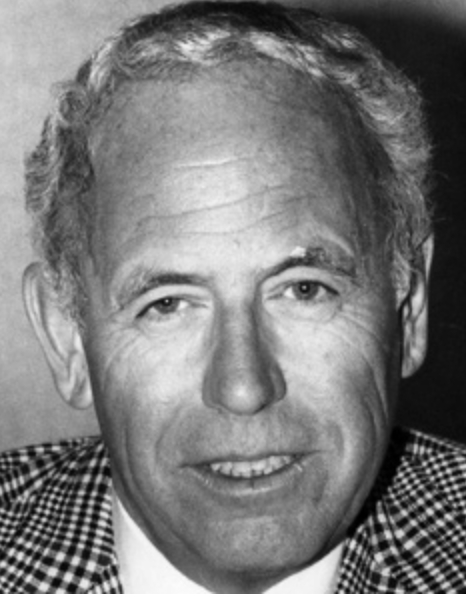

PHOTO: Greene at age 35.

“I prefer to be an agnostic and think that the body itself produces its own miracle.”

— Green 1977 letter to his publicist Ragnar Svanström, quoted in "Graham Greene: A Life in Letters" by Richard Greene (2007)

Philip Pullman

On this date in 1946, acclaimed author Philip Pullman was born in Norwich, England, into a Protestant family. Although his beloved grandfather was an Anglican priest, Pullman became an atheist in his teenage years. He graduated from Exeter College in Oxford with a degree in English and spent 23 years as a teacher while working on publishing 13 books and numerous short stories. Pullman has received many awards for his literature, including the prestigious Carnegie Medal for exceptional children’s literature in 1996, and the Carnegie of Carnegies in 2006.

He is most famous for the His Dark Materials trilogy, a series of young adult fantasy novels which feature freethought themes. The novels cast organized religion as the series’ villain and were written as a secular alternative to C.S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia. Pullman told The New York Times in 2000: “When you look at what C.S. Lewis is saying, his message is so anti-life, so cruel, so unjust. The view that the Narnia books have for the material world is one of almost undisguised contempt. At one point, the old professor says, ‘It’s all in Plato’ — meaning that the physical world we see around us is the crude, shabby, imperfect, second-rate copy of something much better. I want to emphasize the simple physical truth of things, the absolute primacy of the material life, rather than the spiritual or the afterlife.”

In 2007 the first novel of His Dark Materials trilogy was adapted for the motion picture “The Golden Compass” by New Line Cinema. Many churches and Christian organizations, including the Catholic League, called for a boycott of the film due to the books’ atheist themes. While the film was successful in Europe and moderately received in the U.S., the other two books in the trilogy were not adapted, possibly due to pressure from the Catholic Church.

When questioned about the anti-church views in His Dark Materials, Pullman explained in a February 2002 interview for the Third Way (UK): “Every single religion that has a monotheistic god ends up by persecuting other people and killing them because they don’t accept him. Wherever you look in history, you find that. It’s still going on.”

“I don’t profess any religion; I don’t think it’s possible that there is a God; I have the greatest difficulty in understanding what is meant by the words ‘spiritual’ or ‘spirituality.’ “

— Pullman interview, The New Yorker (Dec. 26, 2005)

Tariq Ali

On this date in 1943, scholar and author Tariq Ali was born in Lahore, a city then part of British India, and now in Pakistan. A self-described lifelong atheist, Ali was raised in an intellectually activist family where independent thought was encouraged. His parents were Mazhar Ali Khan, a journalist, and Tahira Mazhar Ali Khan, activist and daughter of Sir Sikandar Hyat Khan, who in 1937 became chief minister of the Punjab, a region bordering India and Pakistan.

Ali became politically involved at a young age, organizing demonstrations against Pakistan’s military dictatorship, while studying at the Punjab University. “We grew up in Lahore, which had been one of the most cosmopolitan towns in India. Then you had the partition of India, and you had massive killlings. This is not much talked about these days, but nearly two million people died, as Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs slaughtered each other to create this state.,” he said in 2003.

Finishing his university education at Exeter College at Oxford, Ali studied philosophy, politics and economics. Elected president of the Oxford Union debating club during the Vietnam War, he debated Henry Kissinger. More and more critical of American/Israeli foreign policies, Ali eventually became the voice of criticism against American foreign policy around the world, not the least of which has been his criticism of American policy in Pakistan.

An active voice for the New Left Review for the past 40 years, Ali is a vocal and prolific personage, writing political satires as well as political historical works, historical fiction, nonfiction and political essays. He owned his own independent television production company and has been a regular broadcaster for BBC Radio. His lengthy bibliography, spanning from 1970 to the present, includes Conversations With Edward Said (2005), which he edited, Rough Music: Blair, Bombs, Baghdad, London, Terror (2005), Speaking of Empire and Resistance (2005), and a previously censored screenplay about the last days of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, titled “The Leopard and The Fox,” originally written in 1985, which, in October 2007, was adapted and staged as a play.

Ali lives in London with his longtime partner Susan Watkins, editor of the New Left Review. He has three children.

PHOTO: Ali in 2010. CC 2.0 photo.

“How often in our house had I heard talk of superstitious idiots, often relatives, who hated a Satan they never knew and worshipped a God they didn’t have the brains to doubt?”

“I grew up an atheist. I make no secret of it. It was acceptable. In fact, when I think back, none of my friends were believers. None of them were religious. Maybe a few were believers but very few were religious in temperament.”

— Ali, “Clash of Fundamentalisms: Crusades, Jihads and Modernity,” 2002; "Islam, Empire, and the Left: Conversation With Tariq Ali," UC-Berkeley, May 8, 2003

José Saramago

On this date in 1922, José Saramago was born in Azinhaga, Santarém, Portugal. He dropped out of school when he was 12 to become a mechanic and later worked as a journalist and production manager of the publishing company Estúdios Cor (1958-71). After being fired from his position as editor of the newspaper Diário de Lisboa (1971–75), Saramago devoted his time to writing fiction.

He became an innovative and prolific novelist, essayist and poet whose works often contained political and philosophical themes. His novels include The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis (1984), The Stone Raft (1986), All the Names (1997) and Blindness (1995), which was adapted into a film in 2008. Saramago became the first Portuguese-language writer to win a Nobel Prize when he was awarded the prize for literature in 1998. He married Ilda Reis in 1944. They divorced in 1970 and had one daughter, Violante. Saramago later married journalist Pilar del Río.

According to a New York Times Topics post (June 18, 2010), Saramago was “an outspoken atheist, one who maintained that religion is to blame for much of the world’s violence.” In an interview with Inter Press Service on Oct. 21, 2009, Saramago said, “God only exists in our minds.”

He wrote the irreverent Cain (2009) and The Gospel According to Jesus Christ (1991), which describes Christ as an average young man with vices, in contrast to his pious depiction in the bible. In 1992, The Gospel According to Jesus Christ was deemed heretical by the Portuguese government and Saramago chose to go into exile in the Canary Islands. (D. 2010)

“All religions, without exception, have done humanity more bad than good.”

— Saramago, Inter Press Service (Oct. 21, 2009)

Mark Twain

On this date in 1835, America’s iconographic humorist and writer Mark Twain (né Samuel Langhorne Clemens) was born in Florida, Mo. He grew up in Hannibal, which became the inspiration for the setting of his classic books Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. His mother, Jane Lampton Clemens, was an advocate of the downtrodden and “could be beguiled into saying a soft word for the devil himself,” he recalled. His father died when he was 11. Samuel left school to work and by 13 was a journeyman printer at the Hannibal Gazette.

Traveling east to work as a printer and writer, he returned to Missouri to spend two eventful years as a cub pilot on the Mississippi River. His nom de plume was inspired by the call “mark twain” made to signal a safe passage of two fathoms’ depth. Twain worked as a reporter in Nevada and California. When his story “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” was published, he became a national celebrity. He worked as a traveling correspondent and lecturer. Innocents Abroad was published in 1869.

After marrying Olivia Langdon in 1870, he built an opulent house in Hartford, Conn. It was at this home and at his sister-in-law’s farm in Elmira, N.Y., where he produced Tom Sawyer, The Prince and the Pauper, Life on the Mississippi and Huck Finn (1884). Twain’s later works included A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889), “The War Prayer” (a scathing indictment of war and religious hypocrisy, written in 1905 but not published until 1923), The Mysterious Stranger (debunking Providence and published posthumously in 1916) and Letters From the Earth. His daughter Clara delayed publication of this blasphemous yarn told about humans from Satan’s perspective until 1962.

Europe and Elsewhere, containing “The War Prayer” and other freethinking writings, was edited by Albert Bigelow Paine, who also helped edit Twain’s autobiography published in 1923. Pudd’nhead Wilson (1894) begins each chapter with an aphorism from “Pudd’nhead Wilson’s Calendar,” including “There is no humor in heaven.” In Following the Equator (1897), he famously said, “Faith is believing what you know ain’t so.” Twain’s sardonic humor increasingly added indignant social criticism. He called the Book of Mormon “chloroform in print.” In 1907, he wrote Christian Science, exposing Mary Baker Eddy’s “desert vacancy, as regards thought.”

In the late 1890s he became a passionate critic of American imperialism, opposing the Spanish-American and Philippine wars. Twain suffered many personal tragedies, from his brother Henry’s tragic death in a steamboat accident in 1858, the death of his son Langdon at 19 months, the death of his daughter Susie from meningitis at age 24 and the death of his daughter Jean in an institution during an epileptic seizure. His wife Livy died in 1904. (D. 1910)

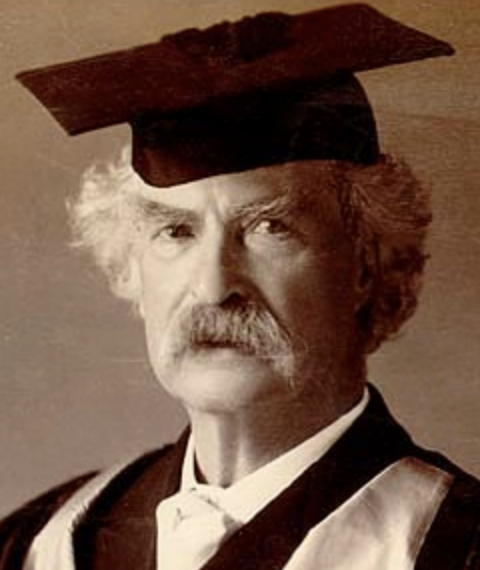

PHOTO: Twain in 1907 receiving a doctor of letters degree from Oxford University.

“I cannot see how a man of any large degree of humorous perception can ever be religious — except he purposely shut the eyes of his mind & keep them shut by force.”— "Mark Twain's Notebooks and Journals, Notebook 27, August 1887-July 1888," ed. Frederick Anderson (1979)