composers

Javed Akhtar

On this date in 1945, Javed Akhtar (né Jadoo Akhtar) was born in Gwalior, India. His father was an Urdu poet and Bollywood songwriter, and his mother was a teacher and writer. Akhtar earned a bachelor’s degree from Saifia College in Bhopal, then moved to Mumbai in 1964, where he worked as a scriptwriter. In the 1980s he focused on writing lyrics for films. He has written lyrics for over 70 films, for which he has received several National Film Awards. In 2001 he received the National Integration Award from the All-India Anti-Terrorist Association. He serves on the advisory board of the Asian Academy of Film and Television.

Akhtar married Honey Irani, with whom he had two children, Farhan and Zoya Akhtar, both film directors and actors. After divorcing, Akhtar married Shabana Azmi, the daughter of Urdu poet Kaifi Azmi.

Muslims “have to improve their lot by lending strength to secular forces and by becoming more and more secular themselves,” he said in an interview with the Times of India. (“Questions and Answers,” March 28, 2002.) “Arms, drugs and spirituality – these are the three big businesses in the world. … Spirituality nowadays is definitely the tranquilizer of the rich,” he said in a 2005 speech at the India Today Conclave.

“I am an atheist, I have no religious beliefs. And obviously I don’t believe in spirituality of some kind.”

— Akhtar, India Today Conclave speech, “Spirituality: Halo or Hoax?” (Feb. 26, 2005)

Frederick Delius

On this date in 1862, composer Fritz Theodor Albert Delius was born in England to parents who had emigrated from Germany and had 14 children. In 1884 he moved to Florida at his father’s behest to manage an orange plantation, staying for about 18 months. While there he became enchanted with African-American music, which would be documented in his “Florida Suite.” He studied at the Leipzig Conservatorium, then moved to Paris, composing vocal and instrumental works and orchestral pieces along with the operas “Irmelin” and “The Magic Fountain.”

His inspiration derived from the literature of England, Norway, Denmark, Germany and France, medieval romance, North American Indians and African-Americans, the Florida landscape and the Scandinavian mountainscape. His operatic masterpiece was “A Village Romeo and Juliet,” followed by “Appalachia,” “Sea Drift” and “A Mass of Life.” Then came “Songs of Sunset,” “Brigg Fair,” “In a Summer Garden,” the opera “Fennimore and Gerda,” “An Arabesque,” “The Song of the High Hills” and from 1911-12 came the popular “On hearing the first cuckoo in spring” and “Summer night on the river.” He produced many more concertos and orchestral/choral works.

Delius was a lifelong freethinker. He was “always ready to poke fun at the religious beliefs of his friends” (Grieg and Delius: A Chronicle of their Friendship in Letters by Lionel Carley.) In a letter to Edvard Grieg, Delius wrote, “I think the only improvement that Christ and Christianity have brought with them is Christmas. As people really then think a little about others. Otherwise I feel that he had better not have lived at all. The world has not got any better, but worse & more hypocritical, & I really believe that Christianity has produced an overall submediocrity & really only taught people the meaning of fear.” (Carley)

Close friend Eric Denby wrote an intimate biography in 1936 of Delius’s final years. “He had no faith in God,” Fenby wrote, “Nevertheless … my admiration for Delius’s music will in no wise have suffered thereby.” Fenby, a strong believer, often found himself a helpless punching bag for Delius’s criticisms of religion. “God? I don’t know him. Given a young composer of genius, the surest way to ruin him is to make a Christian of him.”

Delius married the German artist Jelka Rosen, a friend of Auguste Rodin and a regular exhibitor at the Salon des Indépendants, in 1903. They shared a passion for the works of Nietzsche and Grieg and moved to Grez-sur-Loing, a village 40 miles from Paris, where they lived together for the rest of their lives except for a period during World War I. They had no children and he was not a faithful husband, which Jelka seemed to accept. Delius was increasingly affected by the symptoms of syphilis that he had probably contracted in the 1880s. By 1928 he was partially paralyzed and blind. He died at age 72 in 1934. She died the next year and they share a grave in England. (D. 1934)

“The sooner you get rid of all this Christian humbug the better. The whole traditional concept of life is false. Throw those great Christian blinkers away, and look around you and stand on your own feet. … Don’t believe all the tommyrot priests tell you; learn and prove everything by your own experience.”

— Delius, quoted in "Delius As I Knew Him" by Eric Denby (1936)

Anthony Burgess

On this date on 1917, Anthony Burgess (né John Anthony Burgess Wilson) was born in Manchester, England. His mother and sister died in the 1918 flu pandemic. The author of 50 books, he is best known for his novel A Clockwork Orange (1962), which was made into a movie directed by Stanley Kubrick in 1971. Burgess was also a translator, critic, composer, librettist and screenwriter. He wrote at least 65 musical compositions and preferred to be called “a musician who writes novels.”

He was educated at a Catholic college and graduated from Manchester University in 1940. He joined the British Army Education Corps, which entertained troops in Europe, and was stationed in Gibraltar. Burgess later said a World War II sexual assault by four American deserters on his first wife, Llewela Isherwood Jones, partly inspired his examination of violence in A Clockwork Orange.

He taught after the war and was a distinguished professor at the City College of New York, 1972-73.

“The ideal reader of my novels is a lapsed Catholic and failed musician, short-sighted, color-blind, auditorily biased, who has read the books that I have read,” he told The Paris Review in a 1973 interview. According to his 1993 New York Times obituary, he also once said, “I don’t think there’s a heaven, but there’s certainly a hell. Everything we’ve experienced on earth seems to point toward the permanence of pain.”

“I was brought up a Catholic, became an agnostic, flirted with Islam and now hold a position which may be termed Manichee. I believe the wrong God is temporarily ruling the world and that the true God has gone under. Thus I am a pessimist but believe the world has much solace to offer: love, food, music, the immense variety of race and language, literature and the pleasure of artistic creation.”

— Burgess, New York Times obituary (Nov. 26, 1993)

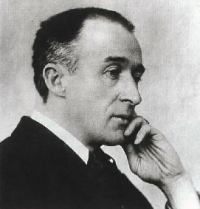

Maurice Ravel

On this date in 1875, Joseph Maurice Ravel, composer, pianist and conductor, was born in the Basque town of Ciboure, France. His father, Pierre-Joseph Ravel, was an educated engineer, inventor and manufacturer. His mother, Marie (née Delouart) Ravel, was born to an unwed mother and was barely literate. She was also a freethinker, a trait inherited by Maurice, who was always politically and socially progressive as an adult, according to musicologist and Ravel scholar Arbie Orenstein.

He was admitted to France’s premier music academy, the Conservatoire de Paris, winning first prize in the school’s piano competition in 1891. He was expelled in 1895 due to differences with faculty conservatives but was readmitted two years later and studied composition with Gabriel Fauré. He was later forced out again after clashing with Conservatoire Director Théodore Dubois, who deplored Ravel’s musical and political progressivism.

Making his way as an orchestral arranger and composer, he was often associated with his contemporary Claude Debussy as an impressionist, though neither liked the term. He liked to experiment with musical form, as is evident in “Boléro” (1928), his best-known work. “Boléro” is a one-movement orchestral piece originally composed as a ballet that repeats its main melody 18 times by solo or combinations of instruments. The duration varies depending on the tempo but typically is about 16 minutes. When Toscanini conducted it faster, Ravel objected, resulting in hard feelings. “When I play it at your tempo, it is not effective,” Toscanini said. To which Ravel supposedly replied, “Then do not play it.”

Ravel, a master of orchestration, worked at a slower pace than many of his contemporaries. Among his 85 works, many incomplete, are pieces for piano, chamber music, two piano concertos, ballet music, two operas and eight song cycles. He wrote no symphonies or church music. He was among the first to realize the potential of recording music. According to a 1914 article in the French magazine Comoedia illustré, there’s “a notable absence of religious forms or references” in his works. “His habitual inspiration came from nature, from fairy tales and folk songs, and from classical and Oriental legends. Nor was he always sympathetic to the religious works of other composers.”

Although he never married and was childless, Ravel liked children and wrote piano music they could play and reflected their world. He wrote “Ma Mère l’Oye” (Mother Goose), subtitled “cinq pièces enfantines” in 1910 as a duet and dedicated it to his students, Mimie Godebska and her brother Jean. “It was he who made me read the Fioretti (Little Flowers) of St. Francis of Assisi. Although he was a confirmed atheist, he adored this book, and I was so amazed by it that I used to imagine it being set to music — by Ravel,” wrote Mimie Godebska Blacque-Belair in 1938.

Ravel started to suffer from neurological impairment in the early 1930s, which affected his piano playing, touring and conducting. The cause was never determined but may have been dementia, Alzheimer’s or Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. He died at age 62 and was buried next to his parents with no religious ceremony. (D. 1937)

PHOTO: Ravel at age 50.

“What you write to me about the benefits of religion, we have spoken of it with Pierrette Haour, an atheist like me.”

— Ravel letter in 1920 to Ida Godebska, cited in "Maurice Ravel: lettres, écrits, entretiens" (letters, writings, interviews), Arbie Orenstein, ed., (1989)

Béla Bartók

On this date in 1881, composer, pianist and ethnomusicologist Béla Bartók was born in Nagyszentmiklós, Hungary. He and Franz Liszt are regarded by many as the greatest Hungarian composers. Trained in piano and composition at the Budapest Academy of Music, Bartók began his career as a touring pianist in 1903. His talents as a composer soon became apparent, and Bartók assumed a professorship at the academy in 1908.

He drew inspiration from the folk music of the Balkans and other regions while engaging in intense studies of harmonic practices, including those of contemporary French composers. While not an expert in stringed instruments, Bartók’s compositions displayed a preternatural understanding of the violin: “He enriched [the violin’s] repertoire with such essential works as his two Sonatas for Violin and Piano (of 1921 and 1922, respectively), two Rhapsodies for Violin and Orchestra (1928-29), 44 Duos for Two Violins (1931), and the Sonata for Solo Violin (1944).” (New York Philharmonic)

His childhood Catholicism was gone by early adulthood. “By the time I had completed my 22nd year, I was a new man — an atheist.” (Béla Bartók: Life and Work by Benjamin Suchoff, 2001) He later became attracted to Unitarianism and publicly converted in 1916. A committed anti-fascist, Bartók opposed Hungary’s alliance with Germany in World War II and refused to perform in Germany during Nazi rule.

He married Márta Ziegler in 1909 when he was 28 and she was 16. They divorced in 1923 and he married Ditta Pásztory, a piano student, two months later when she was 19 and he was 42. He had two sons, Béla Bartók III and Péter. Bartók and Ditta emigrated to the U.S. in 1940 and he accepted a research fellowship at Columbia University, where they compiled a large collection of Serbian and Croatian folk songs for Columbia’s libraries. He died at age 64 in New York from complications of leukemia. (D. 1945)

PHOTO: Bartók’s portrait on a 1,000-forint banknote. Hungarian National Bank photo. GNU Free Documentation License

“To violinist Stefi Geyer, he once wrote about his religious belief, calling the trinity a ‘clumsy fable’ that ‘enslaves thought.’ … The existence of the universe did not require the hypothesis of a creator. ‘Why don’t we simply say: I can’t explain the origin of its existence and leave it at that?’ “

— "Béla Bartók" by David Cooper (2015)

Sergei Prokofiev

On this date in 1891, one of the 20th century’s most popular composers, Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev, was born in Sontsovka in what is now Ukraine. Prokofiev composed works in many genres, including the opera “War and Peace,” the ballet “Romeo and Juliet,” the children’s piece “Peter and the Wolf,” for which he is best known in the West, and the score for the film “Alexander Nevsky” (1938).

Prokofiev was not raised in a religious household and never used an explicitly religious setting. His opera “The Fiery Angel” addressed religious themes but is not complimentary to organized religion. Some of his early works such as the “Scythian Suite” were inspired by Russian folklore and paganism. Prokofiev showed a talent for piano and composition at a very young age and was encouraged in this by his mother, who also took him to musical performances. In 1904 he and his mother moved to St. Petersburg, where he studied at the St. Petersburg Conservatory for 10 years.

Following the Revolution, Prokofiev spent most of his time outside of the Soviet Union, only returning occasionally and never formally accepting Soviet citizenship. He married the Spanish singer Lina Llubera in 1923, and they moved to Paris. They had two sons together. In the spring of 1936, when commissions were hard to come by from Western patrons, Prokofiev moved to Moscow along with his family.

After this time, he only left the USSR once, on a tour of America. He married Mira Mendelson in 1948 after leaving Lina in 1941. Prokofiev survived the purges but the tensions and times took a toll on his health. He had gradually fallen out of favor with Stalin and had few friends at the time of his death at age 61, having outlived Stalin by perhaps a few minutes. Because of the period of mourning for Stalin, Prokofiev’s funeral was small and news of his death was not widely reported. (D. 1953)

“At home we didn’t talk about religion. So, gradually the question faded away by itself and disappeared from the agenda. When I was nineteen, my father died; my response to his death was atheistic.”

— Prokofiev, "Sergei Prokofiev: A Biography" by Harlow Robinson (1987)

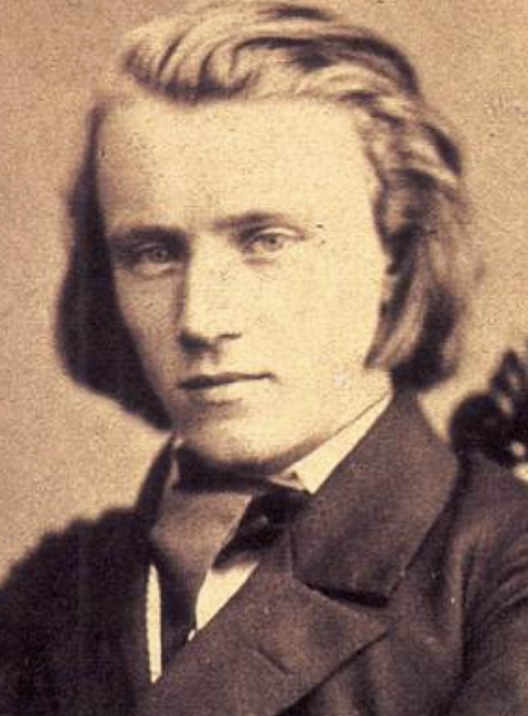

Johannes Brahms

On this date in 1833, Johannes Brahms was born into a Lutheran family in Hamburg, Germany. His father gave him his first musical training on the violin and cello. He studied piano at age 7 with Otto Friedrich Cossel, who complained in 1842 that Brahms “could be such a good player, but he will not stop his never-ending composing.” By 1845 he had written a piano sonata in G minor. His parents disapproved of his early efforts as a composer, feeling that he had better career prospects as a performer.

His reputation and status as a Romantic composer and a master of counterpoint, rhythm and meter are such that he is sometimes grouped with J.S. Bach and Beethoven as one of the “Three Bs” of music.

Brahms was well-read in philosophy and science and was an avid hiker who took inspiration from nature. When a conductor requested a greater religious consciousness in the text of some liturgical music, Brahms responded that he would prefer to “dispense with passages like John 3:16” and “gladly omit even the word German and instead use Human.” (Jan Swafford, Johannes Brahms: A Biography, 1997.)

A liberal, Brahms ardently opposed anti-Semitism, was approachable even at the height of his fame, and was always generous with his time and charity. Swafford wrote, “Though he was to be a freethinker in religion, Johannes pored over the Bible beyond the requirements for his Protestant confirmation.” From then on, “Music was Brahms’ religion.” According to Swafford, Brahms was “a humanist and an agnostic.”

He never married although it was obvious he loved children. Scholars have observed that he thought himself as unfit emotionally for marriage. He died of liver cancer at age 63. (D. 1897)

PHOTO: Brahms at age 20.

“Yet we can’t believe in immortality on the other side. The only true immortality lies in one’s children.”— Brahms' letter to composer Richard Heuberger, "Johannes Brahms: A Biography" by Jan Swafford (1997)

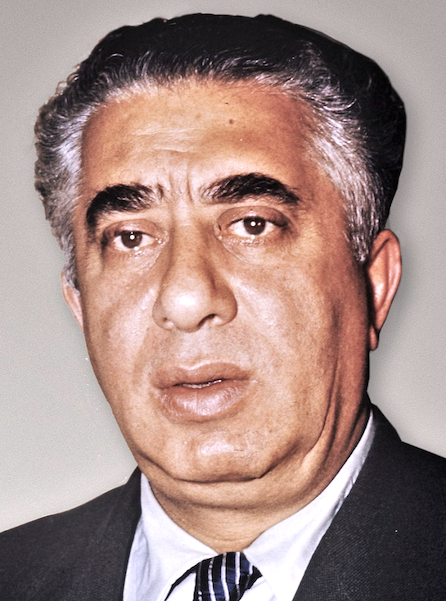

Aram Khachaturian

On this date in 1903, composer Aram Ilyich Khachaturian was born in Tiflis (now Tbilisi), the capital of Georgia, the youngest of the five children of Kumash Sarkisovna and Yeghia Khachaturian, both of Armenian descent. His parents were betrothed when his mother was 9 and his father, later a bookbinder, was 19.

Khachaturian, along with Dmitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokofiev, is generally considered one of the three greatest composers of the Soviet era in Russia and the other republics. He studied at the Gnessin Musical Institute (while simultaneously studying biology at Moscow State University) and became proficient in composition and orchestration at the Moscow Conservatory.

His first major work, the Piano Concerto in D-flat major (1936), popularized his name inside and outside the Soviet Union as did his later concertos for violin and cello. Other significant compositions included the “Masquerade Suite” (1941), the “Anthem of the Armenian SSR” (1944), three symphonies (1935, 1943, 1947) and about 25 film scores.

Khachaturian is known for his ballet music: “Happiness” (1939), “Gayane” (1942), which was his wife’s nickname, and “Spartacus” (1954). “Sabre Dance” from “Gayane” is his best-known work. He married composer Nina Vladimirovna Makarova, a fellow student at the Moscow Conservatory, in 1933. They had a son, Karen, and daughter, Nune.

After 1950 he taught at the Gnessin Institute and the Moscow Conservatory and turned to conducting, traveling throughout Europe, Latin America and the U.S. with concerts of his own music. In 1957 he became secretary of the Union of Soviet Composers, a position he held until his death.

Khachaturian used Armenian and, to a lesser extent, Caucasian, Eastern and Central European and Middle Eastern folk music in his works. He is considered a “national treasure” in Armenia. “Besides his being an atheist, his Armenian descent grated against the patriotism and chauvinism of the Euphratians,” Leo Hamalian wrote in 1980 in “As Others See Us: The Armenian Image in Literature.”

He died just short of his 75th birthday after a long illness, two years after his wife’s death. D. 1978.

I’m an atheist, but I’m a son of the [Armenian] people who were the first to officially adopt Christianity and thus visiting the Vatican was my duty.”

— Khachaturian, when asked about his visit to the Vatican, Solomon Volkov, Novoye Vremya (Aug. 22, 2014)

Charles Strouse

On this date in 1928, composer Charles Strouse was born in New York City to Ira Strouse, a traveling salesman, and Ethel (Newman) Strouse, a homemaker and amateur pianist. The composer of the musical “Annie” (“The sun’ll come out tomorrow”), “Bye Bye Birdie” (“Gray skies are gonna clear up. Put on a happy face”) and the song “Those Were the Days” (on which he played the piano) from the TV show “All In The Family,” became an inseparable part of the fabric of modern popular American music.

His songs have been performed by almost every major vocalist, including Barbra Streisand, Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Bobby Darin, Mandy Patinkin, Harry Connick Jr., Bobby Rydell, Jay Z, Vic Damone, Louis Armstrong, Nina Simone, Grace Jones and Duke Ellington and his Orchestra.

Strouse grew up in Manhattan with a father plagued with serious health problems and a mother who was institutionalized for two years in a psychiatric hospital. He enrolled in the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, N.Y., majoring in composition, and earned a bachelor’s degree in 1947.

Strouse wrote the score to over 30 stage musicals, 14 scores for Broadway (including “Applause,” starring Lauren Bacall, and “Golden Boy,” starring Sammy Davis Jr.), four Hollywood films (including “Bonnie and Clyde,” 1967, and “All Dogs Go To Heaven,” 1989), two orchestral works and an opera. He has been inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame and the Theatre Hall of Fame. He is a three-time Tony Award winner, a two-time Emmy Award winner, and his cast recordings have earned him two Grammys.

With hundreds of productions licensed annually, “Annie” and “Bye Bye Birdie” are among the most popular musicals of all time produced by regional, amateur and school groups all over the world. He “discovered” Sarah Jessica Parker, backing her selection to play the lead in “Annie” after the originator of the Broadway role outgrew it. Strouse married Barbara Siman, a director and choreographer, in 1962. They had four children.

“I grudgingly went to Sunday Hebrew school,” Strouse wrote in his 2008 memoir Put on a Happy Face. “We were not what you would call religious, and this has stuck with me to this day.” He described a full and purpose-filled life, working for music as well as civil rights (a theme of “Golden Boy”). He traveled as an accompanist with actress Butterfly McQueen, experiencing firsthand the racial discrimination she faced in the South. He marched with Sammy Davis Jr., in Selma, Ala., in 1965.

“Though my father wasn’t an atheist, I am,” he said on Freethought Radio (June 20, 2009). “I understand why people do believe [in God] and frankly, I’m a little puzzled, though a little pleased, that there is a radio program like yours that talks about it, because as an atheist, at least my kind of it, I don’t need any persuasion. I’ve been persuaded for a great number of years now, by the wars, the calamities, the religious antagonism among people and their stupid rules.”

In 2011 at FFRF’s 34th national convention in Hartford, Conn., he graciously accepted an Emperor Has No Clothes Award given to public figures who make known their dissent from religion. He died in Manhattan at age 96. He and his wife, who died in 2023, were married 61 years. (D. 2025)

PHOTO: Strouse in 2013; GustavM photo under GNU 1.2.

“My sister died in ’41 of breast cancer, and I remember a rabbi saying that ‘God in his infinite wisdom has chosen to take this young girl.’ That was a point in my life that I said there couldn’t be any God.”

— Strouse on Freethought Radio (June 20, 2009)

Richard Strauss

On this date in 1864, composer Richard Strauss was born in Germany. Strauss began piano lessons at age 3 and composition by 7. He studied music and philosophy for two terms at Munich University and launched into a career as a conductor. His teenage composition was influenced by the work of Robert Schumann. His piano quartet of 1884 was completed following a consultation with Johannes Brahms, but the adult Strauss was influenced by Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner.

He excelled in the tone poem (including “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” setting to music Nietszche‘s and his own views), and opera. His opera “Salome” (1905), based on the play by Oscar Wilde, was a sensation not just because of the “blasphemous” subject matter but because it was a musical stretch. Another Strauss opera was “Electra” (1909). His compositions include the tone poem “Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks,” later performed as a ballet with choreography by Nijinsky. He wrote his first songs as a wedding present for his wife, Pauline von Ahna, whom he married in 1894.

Strauss composed the Olympic hymn for the 1936 games in Berlin. He was briefly appointed head of state music (without his consultation) by the Third Reich. He was barred from working with his librettist, Stefan Zweig, who was Jewish, and it is believed he maintained silence about the Nazis in part because his grandchildren were part Jewish. He received warnings about his private letters, which were screened by authorities. Strauss spent much of the war in Vienna, moving to Switzerland at the war’s conclusion. He conducted for the final time when he turned 85. D. 1949.

“When during my stay in Egypt I became familiar with the works of Nietzsche, whose polemic against Christianity was particularly to my liking, the antipathy which I had always felt against a religion which relieves the faithful of responsibility for their actions (by means of confession) was confirmed and strengthened.”

— Strauss, quoted in "Recollections and Reflections" (ed. Willy Schuh, 1949)

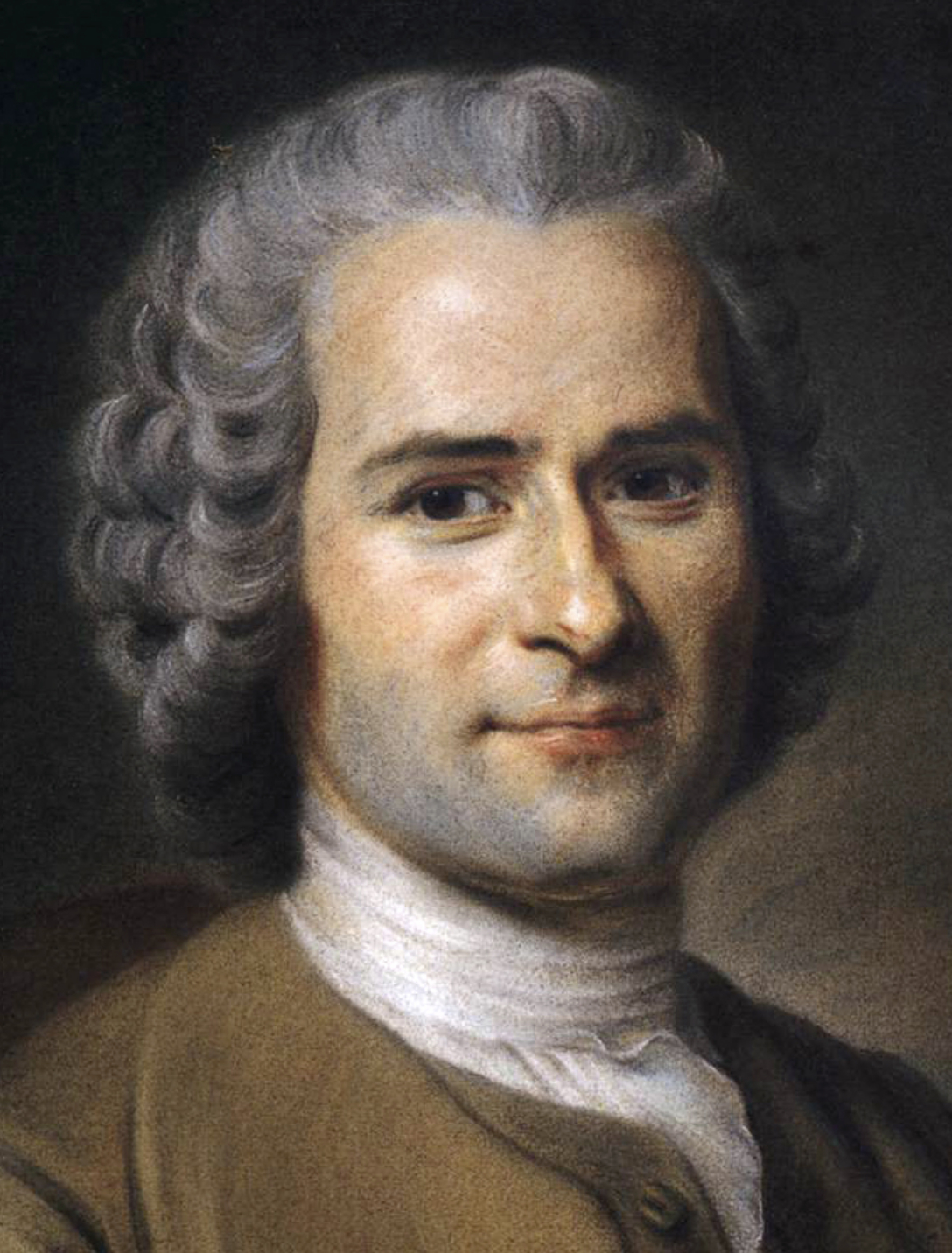

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

On this date in 1712, Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born in Geneva, Switzerland, of French Huguenot parents. His mother died giving birth to him. As a young lad he was apprenticed to an engraver but ran away at age 16 and went into domestic service. His Catholic employer, Mme. De Warens, took him as her lover and allowed him to study literature and philosophy.

In 1741 he moved to Paris and met freethinkers Diderot and D’Holbach, and was asked to write about music for the Dictionnaire Encyclopedique. Rousseau is known for promulgating the idea of the “noble savage” living in a “state of nature,” but intellectual historian Arthur Lovejoy wrote that that misrepresents Rosseau’s thinking.

While living with wealthy patrons, Rousseau worked for eight years writing the novel Julie, ou la nouvelle New Heloise (1760), The Social Contract (1762) and Emile (1762), a treatise on education. The Social Contract introduced the motto “Liberte, egalite, fraternite.” As a Deist with kind words for the gospels, Rousseau was less radical about religion than his friends, perhaps more interested in pursuing his romantic vision of human nature: “Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains.” He believed in a “religion of man.”

Despite Emile’s sympathetic words for the rights of children, Rousseau gave the five illegitimate children he fathered with a hotel maid to foundling homes. His Letters Written to Montaigne (1762) promoted freedom from the church. His arrest was ordered in Paris after publication of Emile and he fled to Switzerland, where officials, in addition to condemning Emile, also condemned The Social Contract and expelled him. Rousseau took refuge in Neuchatel under the King of Prussia but was eventually driven out for his “irreligion.”

He wrote Confessions in England and resettled in Paris in 1770. Freethought biographer Joseph McCabe wrote, “His character was far inferior to that of the ‘irreligious’ Deists of Paris. He was, in fact, the most religious and least virtuous of ‘the philosophers’; far inferior in nobility of character to the Agnostics Diderot and D’Alembert, and more faulty than Voltaire. We must, however, not forget his unhappy circumstances and temperament. He rendered monumental service to his fellows.” (A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists.) (D. 1778)

PHOTO: Portrait of Rosseau by Maurice Quentin de La Tour, 1753.

“Whoever dares to say: ‘Outside the Church is no salvation,’ ought to be driven from the State.

But I am mistaken in speaking of a Christian republic; the terms are mutually exclusive. Christianity preaches only servitude and dependence. Its spirit is so favorable to tyranny that it always profits by such a regime. True Christians are made to be slaves, and they know it and do not much mind: this short life counts for too little in their eyes.”

— Rousseau, "The Social Contract" (1762)

Frank Loesser

On this date in 1910, Frank Loesser was born in New York City. Loesser came from a musical family. His father taught classical piano, and his brother, Arthur Loesser, was a concert pianist. Loesser wrote his first song when he was 4 and soon taught himself to play harmonica and piano. He briefly attended the City College of New York but dropped out and turned to various jobs, including newspaper editing. In 1931 he teamed up with William Schuman to write his first lyrics for the song “In Love With a Memory of You.”

Loesser became an accomplished lyricist for such well-known songs as “Moon of Manakoora” (1943), with music by Alfred Newman, “Two Sleepy People” (1938) and “Heart and Soul” (1938), both with music by Hoagy Carmichael. His musical work is just as famous, including such hits as “If I Were a Bell” (1950), “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” (1944), “Luck Be A Lady” (1950) and “On a Slow Boat to China” (1948).

Loesser contributed scores for many celebrated Broadway musicals, including “Guys and Dolls” (1950), “The Most Happy Fella” (1956) and “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying” (1961). He also wrote the score for the film “Hans Christian Andersen” (1952), comprised of songs such as “Wonderful Copenhagen” and “Anywhere I Wander.”

He married twice and had three daughters and a son. In daughter Susan Loesser’s book A Most Remarkable Fella: Frank Loesser and the Guys and Dolls in His Life (1993), she wrote that his family was not religious. His grandparents “were Jewish by blood, but not by thought or deed. No religion was practiced at home.” Loesser’s father, Henry Loesser, “cultivated intellectual, not theological, fields.” Before Loesser died, he wrote that he wanted his body to be disposed of “without benefit of ceremony, [or] religion.” (D. 1969)

“What a blessing to know there’s a devil, and that I’m but a pawn in his game / that my impulse to sin doesn’t come from within, and so I’m not exactly to blame.”

— Frank Loesser (ironically) in "What a Blessing" (1960)

Leoš Janáček

On this date in 1854, Czech composer and librettist Leoš Janáček was born in Hukvaldy, Moravia, then part of the Austrian Empire. Baptized as a Catholic, at age 11 he became a ward of the foundation of the Abbey of St. Thomas in Brno, took part in choral singing and played the organ and piano. In 1874 he enrolled at the Prague Organ School and graduated with high marks.

He began earning a living in Brno as a music teacher and choir director while writing his first vocal compositions. One student was Zdenka Schulzová. They married when he was 27 and she was 15. In association with the Augustinian Monastery, he founded a college of organists and directed the group until 1919. He also directed the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra from 1881-88.

Janáček was a prolific composer of orchestra, chamber and vocal works, from operas to church music, and was a folklorist during one period, using a repertoire of folk songs and dances in orchestral and piano arrangements. In 1919 he became a professor of composition at the Prague Conservatory. Along with Antonín Dvořák and Bedřich Smetana, he’s considered one of the most important Czech composers.

He was prone to rejecting conventional religious beliefs and disclaimed any faith in an afterlife. In 1918 he wrote to Zdenka: “[Playwright Gabriela] Preissová believes in the soul and in its wandering, and I know that all is just a process of life which ends so quickly — and there is no continuation. And I’d like now to live long.”

After the deaths of two children, his son Vladimir in 1890 and daughter Olga in 1903, the couple’s marriage foundered, hampered by Janáček’s attraction to other women. While the couple remained together, it was a marriage in name only until his death at age 74. (D. 1928)

“Today they are lifting the bells into the tower. It would be nice if they weren’t calling people to bamboozling.”

— Janáček commenting on an archbishop's consecration of new church bells in July 1926. "The riddle of life: The letters of Leoš Janáček to Kamila Stösslová" (1990)

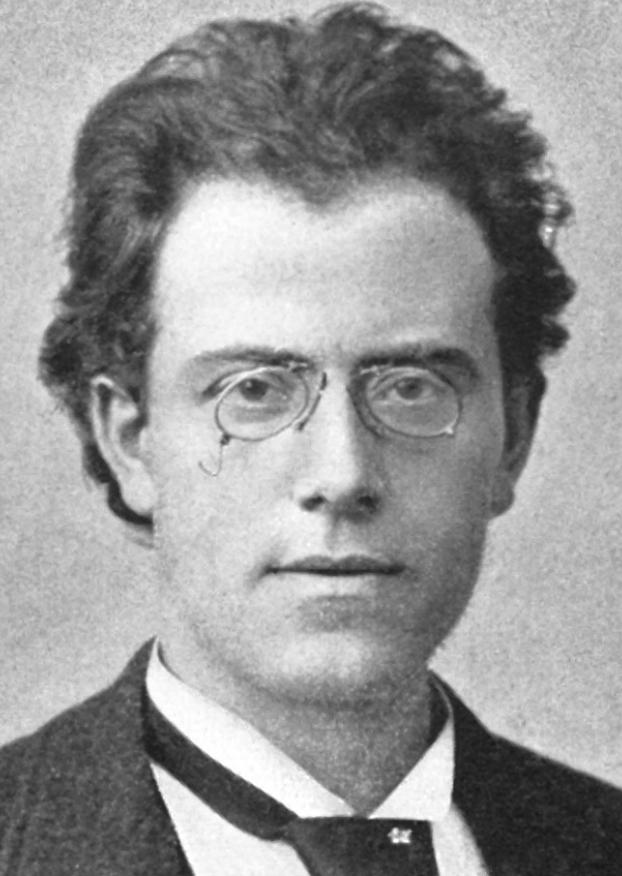

Gustav Mahler

On this date in 1860, Gustav Mahler was born to working-class, Jewish parents in Austrian Bohemia, the second of 14 children. A musical wunderkind, he studied at the Vienna Conservatory as a boy. Mahler’s oeuvre is relatively limited; for much of his life composing was necessarily a part-time activity while he earned his living as a conductor. Aside from early works, his works are generally designed for large orchestras, symphonic choruses and operatic soloists.

At age 37 he faced a dilemma: He could become the director of the prestigious Imperial Vienna State Opera only if he abandoned Judaism and converted to Catholicism. Under the anti-Semitic laws, no Jew — no matter how talented or skilled — could occupy such an exalted position. Though nowhere near a devout Jew, he recognized that conversion was his only ticket to the position. He reportedly commented after the service was over, “I’ve just changed my coat.”

He married Alma Schindler in 1902 when she was pregnant with their daughter Maria. The year before he had started composing his masterful Fifth Symphony (its “Adagietto” movement was played at Sen. Robert Kennedy’s 1968 funeral Mass).

A second daughter, Anna, was born in 1904. Both girls fell ill in 1907 with scarlet fever and diphtheria. Anna recovered but Maria died two weeks later. That same year, Mahler was diagnosed with a congenital heart defect and restrictions were put on his activities. He made his New York debut at the Metropolitan Opera on Jan. 1, 1908, when he conducted Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde.”

He died in Vienna from bacterial endocarditis and pneumonia at age 50. Alma outlived him by 53 years and married twice more, including to architect Walter Gropius. (D. 1911)

“After his baptism, he never again attended Mass, and upon his untimely death in 1911 at age 50, there was no religious funeral service of any kind, nor any religious markings on his gravestone.”

— Rabbi A. James Rudin, "Unconventional Converts," Religion News Service (June 5, 2009)

Woody Guthrie

On this date in 1912, singer-songwriter Woodrow Wilson Guthrie was born in Okemah, Okla., to musically inclined parents Nora Belle (Sherman) and Charles Guthrie. It’s hard to categorize Guthrie, who rose to fame during the Great Depression as champion of the dispossessed and downtrodden, as one thing or another. He was poet, philosopher, political revolutionary, environmentalist, an admirer of Jesus Christ who scorned organized religion.

His life was filled with tragedy early on and ended that way. His sister fatally set herself on fire during an argument with their mother when he was 7, his father was severely burned in a home fire and Woody’s firstborn died at age 4 when she was burned in an electrical fire. His mother was committed to the Oklahoma Hospital for the Insane when he was 14, while he unknowingly carried the Huntington’s chorea gene that killed them both after long hospitalizations.

Musically inclined like his parents, he dropped out of high school as a senior and began playing for dances with his uncle in Texas. He married Mary Jennings in 1931. They divorced in 1940. He married twice more, to Marjorie Greenblatt (1945–53) and Anneke Van Kirk (1953–56), fathering eight children.

He had headed to California in the Dust Bowl migration, leaving the family temporarily in Texas. He hosted a “hillbilly” music radio show, made friends with people like Will Geer and John Steinbeck and wrote a column titled “Woody Sez” for the communist newspaper People’s World in 1939-40 but never joined the political party. He joined the U.S. Merchant Marine in 1943 and was drafted into the Army in 1945. He wrote patriotic songs backing the U.S. fight against fascism.

Guthrie wrote what became “This Land Is Your Land,” arguably his most famous song, in February 1940. Tired of hearing Kate Smith sing “God Bless America” on the radio, he sarcastically called his song “God Blessed America for Me” before renaming it when it was first recorded in 1944, when God was excised from the title and lyrics. As originally written, it said:

One bright sunny morning in the shadow of the steeple

By the Relief Office I saw my people —

As they stood hungry, I stood there wondering if

God blessed America for me.

Guthrie wrote over 3,000 song lyrics, including fanciful ones for children, songs which have influenced succeeding generations of musicians, most personally his son Arlo. His first album, “Dust Bowl Ballads” (1941), sold more than any other. His songs took the side of the economic refugees and those beset by tragedy against the “interests” and bankers. A line in “Pretty Boy Floyd” sums it up: “Some will rob you with a six-gun / And some with a fountain pen.” He also published two novels, created artworks and wrote numerous published and unpublished manuscripts, poems, prose and plays. Over 400 of his songs are in the Library of Congress.

Baptized as a young adult, he never attended church on a regular basis. Asked once to name the people he most admired, he replied, “Will Rogers and Jesus Christ.” (Ron Briley, History News Network, 2005) To him, Jesus was a working-class carpenter who championed the common people and was betrayed by the rich and their selfish interests.

In Born To Win (ed. Robert Shelton, 1965), Guthrie wrote: “Fear before none. Quiver before nothing. Kneel at no spot. Beg no cure. Be a slave to none and master to none. … Love is the only God I’ll ever believe in.” He came to that conclusion, trying to define what God meant to him, “when I was ready to throw so-called fearful cowardly thieving poisoning religion out my back door.” He once said that while he rarely darkened the door of a church, he “always had a deep love for people who go there.”

By the late 1940s, Guthrie’s health was declining and his behavior was becoming extremely erratic, with loss of muscle control and increasing inability to speak. He was diagnosed with Huntington’s and was hospitalized for nearly 12 years from 1956 until his death at age 55 at Creedmoor Psychiatric Center in Queens Village, N.Y., where the 19-year-old Bob Dylan had visited him in 1960. His ashes were sprinkled into the waters off Coney Island, where he had once lived. (D. 1967)

“Some of the preachers that promise you hamburgers in the hereafter get on my nerves; what I’d really like to do is to give ’em a hunk of blackberry pie right in the face.”

— Guthrie, quoted in "Bring Your Own God: The Spirituality of Woody Guthrie" by Unitarian minister Steve Edington (2012)

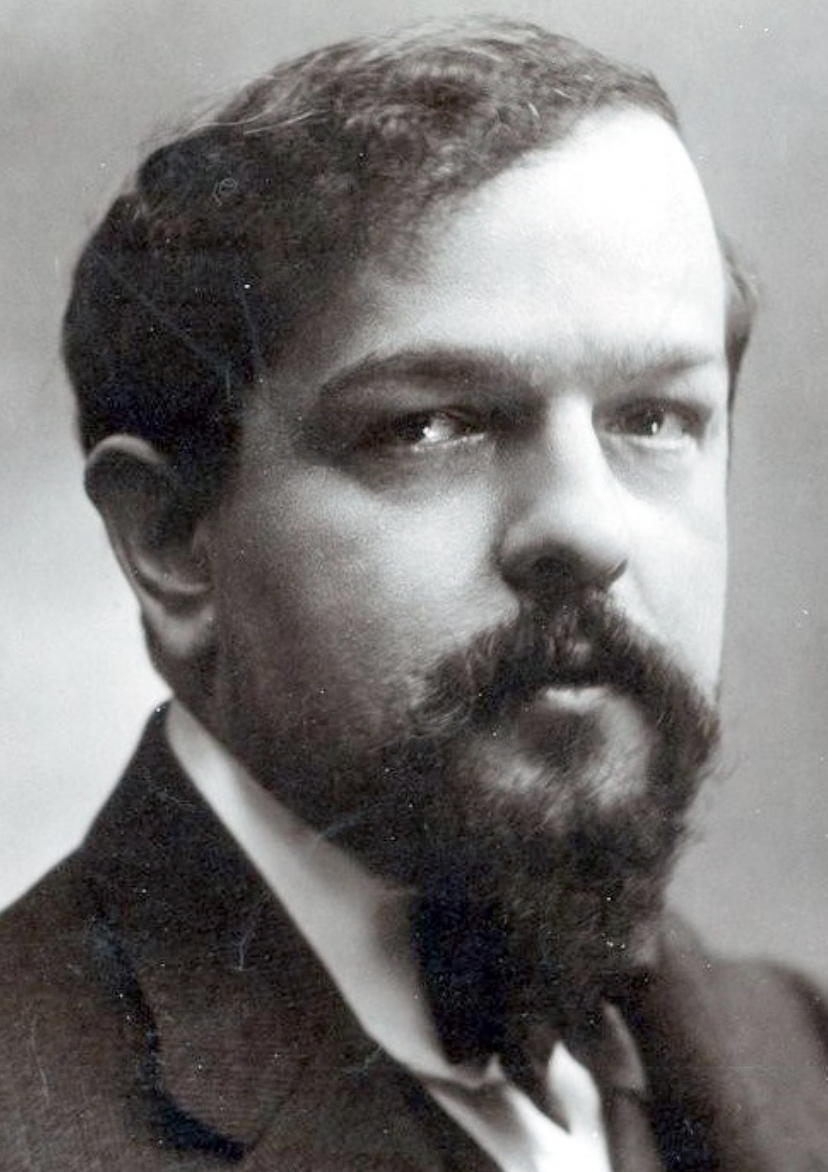

Claude Debussy

On this date in 1862, Achille–Claude Debussy, the originator of “musical impressionism,” was born in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France, the oldest of five children. Becoming a student at the Paris Conservatoire at 11 years old, Debussy went on to win the 1884 Prix de Rome. From 1887 on, he spent his life writing musical compositions, rarely performing.

His most famous works are “Claire de Lune” and the orchestral “Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun,” based on a poem by his friend Stephene Mallarme. His works included orchestral suites, preludes, a ballet and “Pelléas et Mélisande,” his only completed opera.

Debussy married Marie-Rosalie Texier, known as “Lilly,” in 1899 but became increasingly irritated by what he saw as her intellectual limitations and lack of musical sensitivity, according to music scholar Robert Orledge. They divorced in 1904, and in 1905 he married Emma Bardac, who had already given birth to his daughter, Claude-Emma.

In 1915 he underwent one of the earliest colostomy operations after a colon cancer diagnosis. His health continued to decline and he died at age 55 from cancer during the bombardment of Paris by Germany. “His themes — so frequently taken from Mallarme, Verlaine, Baudelaire, etc., — sufficiently indicated his entire rejection of creeds, and he had a secular funeral.” (Joseph McCabe, A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists, 1920) (D. 1918)

PHOTO: Debussy in 1908 at age 46.

“I do not practise religion in accordance with the sacred rites. I have made mysterious Nature my religion. I do not believe that a man is any nearer to God for being clad in priestly garments, nor that one place in a town is better adapted to meditation than another.”

— Debussy, quoted in "Claude Debussy: His Life and Works" by Léon Vallas (1933)

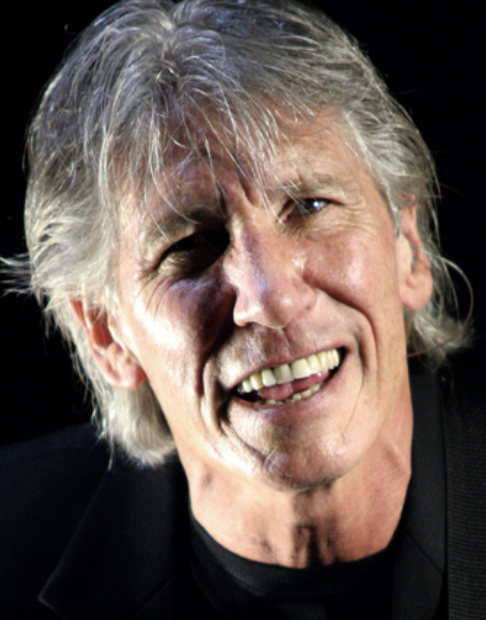

Roger Waters

On this date in 1943, English rock musician and songwriter George Roger Waters, best known for his 20-year career in the band Pink Floyd, was born in Great Bookham, England. Waters met fellow Pink Floyd member and first lead singer Syd Barrett while growing up in Cambridge. David Gilmour, who would replace Barrett as lead singer in 1967 (the band formed in 1965), attended a different school on the same road. Waters met the other band members, Nick Mason and Richard Wright, while studying architecture at the Regent Street Polytechnic in London.

After Barrett’s departure, Waters gained creative control over the band’s music, writing almost all of the lyrics. It was also his idea to create “concept albums” such as The Dark Side of the Moon, Wish You Were Here, Animals, The Wall and The Final Cut. A series of albums the band produced in the 1970s are among the best-selling records of all time. The original band dissolved in 1985 due to creative conflicts but Gilmour ultimately won the legal right, after a contentious public battle with Waters, to continue to use the Pink Floyd name and a majority of the band’s songs.

Since the dissolution, Waters and Pink Floyd have made attempts at reunion shows, benefit concerts and tours. Waters embarked on a solo career after Pink Floyd, with the critically acclaimed album Amused to Death (1992) and a solo world tour starting in 1999, which became so successful it extended to three years. Waters worked on an opera, “Ça Ira,” for 16 years, which was released in 2005.

In an interview with Mark Brown of the Rocky Mountain News, Waters said: “Please, God — I’m an atheist so maybe I shouldn’t be asking God — but let Barack Obama finally win the Democratic nomination and elect a person who seems to be not just enormously intelligent but also deeply humane and seems to have an imagination.” (April 25, 2008.) From his lyrics for “What God Wants, Part I”: “Through the power of money, And the power of your prayers, What God wants God gets God help us all. God wants dollars, God wants cents, God wants pounds shillings and pence. … What God wants God gets God help us all.” (Amused to Death, 1992)

PHOTO: Waters performing in 2007 in São Paulo, Brazil; Daigo Oliva photo under CC 2.0.

“I had some pretty dark and desperate moments all those years ago. … I didn’t ever smash up a hotel room or throw a TV out a window. That was Led Zeppelin. Thank god. If there was a god, you know, which there isn’t.”

— Waters interview from "The Wall Tour," America Online

Dmitri Shostakovich

On this date in 1906, Dmitri Shostakovich was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, with a heritage of proud Siberian roots. His family initially welcomed Lenin and the revolution as a chance for real freedom and equality. Although he became privately disillusioned with the excesses of Stalin, Shostakovich had little choice but to “go through the motions,” eventually joining the Communist Party and fulfilling many official functions as a representative of the government due to his celebrity status as a great composer. He didn’t care about politics, except when he could use his connections to truly help people.

“For me there is no joy in life other than music,” Shostakovich wrote to a friend. “All life for me is music.” The prolific and tireless Shostakovich wrote nine operas and ballets, 37 film scores, 15 symphonies, hundreds of works for choral, solo, piano, concerti, incidental music, chamber and instrumental music. He is one of the most admired composers of the 20th century.

His Eighth Symphony (which he was forced to declare a “war symphony”) was a celebration of life: “I can sum up the philosophical conception of my new work in three words: life is beautiful,” he said during a 1943 interview. “Everything that is dark and gloomy will rot away, vanish, and the beautiful will triumph.” (Shostakovich: A Life, 2000) (D. 1975)

“When asked if he believed in God, his reply was swift and firm: ‘No, and I am very sorry about it.’ ”

— "Shostakovich: A Life" by Laurel E. Fay (2000)

George Gershwin

On this date in 1898, composer George Gershwin (né Jacob Bruskin Gershowitz) was born in Brooklyn, N.Y. Of the three boys in the family, only his older brother Ira, later George’s lyricist, had a bar mitzvah. According to biographer Rodney Greenberg, “This religious milestone apparently meant little to Ira himself. The fact that Rose and Morris never imposed it upon George and Arthur means that, by the time they became teenagers, the family had left their East European Jewish origins behind and were living a secular existence in New York’s cosmopolitan melting pot.”

Gershwin’s named sources of “inspiration” were not gods or prophets but two other nonbelieving songwriters: Irving Berlin and Jerome Kern, according to biographer Edward Jablonski in Gershwin: A Biography. Self-taught on the piano, Gershwin started writing songs as a teen, quickly advancing from Tin Pan Alley to Broadway musicals. Considered by many to be America’s greatest composer, he wrote memorable standard after standard, including “Lady, be Good!” “Strike Up the Band,” “Funny Face,” “The Man I Love,” “Embraceable You,” “Somebody Loves Me” and “They Can’t Take That Away from Me.” His more serious work included “Rhapsody in Blue” (1924), “Piano Concerto in F” (1925), “Porgy and Bess “(1934), and “Three Preludes” (1926).

At the height of his career at age 38 in 1937, he died during surgery to remove a brain tumor. He had never married and at the time of his death lived in a house owned by lyricist Yip Harburg. (D. 1937)

It Ain’t Necessarily So

It ain’t necessarily so, (repeat)

De t’ings dat yo’ li’ble

To read in de Bible,

It ain’t necessarily so.Li’l David was small, but oh my! (repeat)

He fought big Goliath

Who lay down an’ dieth!

Li’l David was small, but oh my!Oh, Jonah, he lived in de whale, (repeat)

Fo’ he made his home in

Dat fish’s abdomen.

Oh, Jonah, he lived in de whale.Li’l Moses was found in a stream, (repeat)

He floated on water

Till Ole Pharaoh’s daughter

She fished him, she says, from that stream.It ain’t necessarily so, (repeat)

Dey tell all you chillun

De debble’s a villun,

But ’tain’t necessarily so.To get into Hebben don’ snap for a sebben!

Live clean! Don’ have no fault.

Oh, I takes dat gospel

Whenever it’s poss’ble,

But wid a grain of salt.Methus’lah lived nine hundred years, (repeat)

But who calls dat livin’

When no gal’ll give in

To no man what’s nine hundred years?I’m preachin’ dis sermon to show,

It ain’t nessa, ain’t nessa,

ain’t nessa, ain’t nessa,

Ain’t necessarily so.— Music by George Gershwin, lyrics by Ira Gershwin (1935)

Sting

On this date in 1951, musician Gordon Matthew Thomas Sumner (Sting), was born to a milkman and hairdresser in Wallsend on Tyne, Northumberland, England. Sumner took the name Sting after someone told him he looked like a bee wearing a striped sweater. He became a husband and father before turning 20 and moved to London hoping to launch his musical career. He and two others started the band The Police in 1976. As lead singer, he wrote most of the music and lyrics.

The group had early hits with “Roxanne” and “Message in a Bottle” but struck musical gold with the 1983 hit “Every Breath You Take.” Sting began acting in such films as “Quadrophenia” (1979), “Dune” (1984) and “The Bride” (1985). The Police broke up in 1984 after winning six Grammys and Sting released his first solo album the next year, “The Dream of the Blue Turtles,” which was nominated for a Grammy. He continued to perform and record and collaborate with other artists, including a 2014-15 world tour with Paul Simon and the next year with Peter Gabriel. His 14th album, “My Songs,” was released in May 2019.

He was married to actress Frances Tomelty from 1976-84. They had two children: Joseph and Fuchsia Katherine. He married actress and film producer Trudie Styler in 1992 after they had been together for a decade. They have four children: Brigitte Michael, Jake, Eliot Pauline and Giacomo Luke.

Sting’s activism has persisted throughout his career. Since the 1980s, he has actively supported Amnesty International, and co-founded the Rainforest Foundation in 1989, in an effort to save the Brazilian rainforest. He has authored books including Jungle Stories: The Fight for the Amazon (1989), with co-author Jean-Pierre Dutilleux, and Spirits in the Material World (1994), with Pato Banton.

In the CD booklet of his Winter Solstice album, “If On A Winter’s Night” (2009), Sting twice identified himself as an agnostic. Answering “What do you think happens when we die?” he once said: “It’s only conjecture, but I imagine it’s the same as it was before I was here. Which makes it incumbent upon us to create a heaven on Earth, now, and not hell.” (“The Late Show with Steven Colbert,” Dec. 10, 2021)

Public domain photo: Sting at the 2014 Kennedy Center Awards.

“[I]f ever I’m asked if I’m religious I always reply, ‘Yes, I’m a devout musician.’ Music puts me in touch with something beyond the intellect, something otherworldly, something sacred.”

— Sting, commencement address, Berklee College of Music in Boston (May 15, 1994)

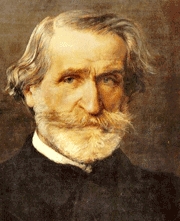

Giuseppe Verdi

On this date in 1813, Italy’s great composer, Giuseppe Verdi, was born to a humble family in Le Roncole, a village near Busseto. He started music lessons with the village church organist at age 7. He was turned away from a conservatory in Milan, but studied privately. His first opera, “Oberto,” was produced at La Scala in 1839. Many operas would follow, including “Rigoletto” (1851), “Il Trovatore” (1853), “La Traviata” (1853) and “Les Vepres Siciliennes” (which was criticized by clergy, 1855).

The composer of “Don Carlos” (1867), “Aida” (1870), “Otello” (1886) and “Falstaff” (1893) was acclaimed internationally and regarded by contemporaries as the greatest Italian composer of his century. Verdi’s early personal life was marked by family tragedies, including the death of his sister at age 17. He married Margherita Barezzi, the daughter of a patron, in 1836 and she gave birth to children in 1837 and 1838 but both died in infancy. Margherita died of encephalitis at age 26.

Verdi was generally anti-clerical and a rationalist. He sympathized with 19th-century campaigns for freedom. At the end of his career, Verdi shared his wealth, endowing the city of Milan with two million lire in 1898 to establish a home for aging musicians, the grounds of which became his final resting place. He also provided funds for a hospital near Busseto.

He married soprano Giuseppina Strepponi in 1859 after they had lived together for several years, a scandalous cohabitation in the eyes of some. She died in 1897. Later in life Strepponi wrote: “I exhaust myself in speaking to him about the marvels of the heavens, the earth, the sea, etc. It’s a waste of breath! He laughs in my face and freezes me in the midst of my oratorical periods and my divine enthusiasm by saying ‘you’re all crazy,’ and unfortunately he says it with good faith.” (Verdi: A Biography by Mary Jane Phillips-Matz, 1993.)

Verdi died of a stroke in 1901 at age 87. “[My funeral is to be without] any part of the customary formulae,” Verdi wrote in his will (cited by F.T. Garibaldi in Giuseppe Verdi, 1903). An estimated 300,000 people came to his memorial service in Milan, where Arturo Toscanini directed musicians and a choir of over 800 voices in Verdi’s Va, pensiero (known as the chorus of the Hebrew slaves) from “Nabucco.” (D. 1901)

“Like many nineteenth-century artists, Verdi was an agnostic whose elevated sense of morality and duty bypassed divine sanction. Strepponi, replying in 1871 to a friend bent on Verdi’s conversion, at first wrote that, with the highest virtues, her husband was an atheist; she then revised this to ‘I won’t say an atheist, but certainly very little of a believer.’ ”

— "The Life of Verdi" by John Rosselli (2000)

Thelonious Monk

On this date in 1917, the American jazz composer and pianist Thelonious Sphere Monk was born in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. When he was 5, his family moved to Manhattan, where he started playing the piano, largely self-taught. His compositions “Round Midnight,” “Well, You Needn’t,” Straight, No Chaser,” “Blue Monk” and others have become standards in the jazz repertoire. “Round Midnight” is the most recorded jazz standard written by a jazz musician, appearing on more than 1,000 albums.

Monk’s idiosyncratic style utilized unexpected melodic twists, dissonant harmonies (which are pleasing to jazz players), erratic percussive phrases punctuated by unexpected hesitations and silences. Despite these unorthodox qualities, Duke Ellington is the only jazz composer who has been recorded more often than Monk, who is one of only five jazz musicians to have been on the cover of Time (along with Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Dave Brubeck and Wynton Marsalis).

Like his music, Monk’s views on religion were also unorthodox. As a teenager, he played the organ for a traveling evangelist, but it appears he was an agnostic who held no religious beliefs of his own. Biographer Robin D. G. Kelly wrote that “Monk clearly was not a true believer” and that “most people who knew Monk remember that he rarely attended church and did not speak about religion in the most flattering terms.”

According to his niece Charlotte, “He was never into religion. Religion was not his thing. … He never went to church or any of that. And his kids, he never took them to church. He said they had to have their own mind about things.” But he was tolerant of religion and sometimes accompanied his mother on the piano as she sang her beloved hymns while she was dying of cancer.

After years of declining health, he died of a stroke at age 64 in Weehawken, N.J. He was posthumously awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award and a Pulitzer Prize Special Citation. (D. 1982)

PHOTO: Monk in 1947. William P. Gottlieb photo, Library of Congress.

INTERVIEWER: “Do you believe in God?”

MONK: “I don’t know nothing. Do you?”— "Thelonius Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original" by Robin D. G. Kelley (2009)

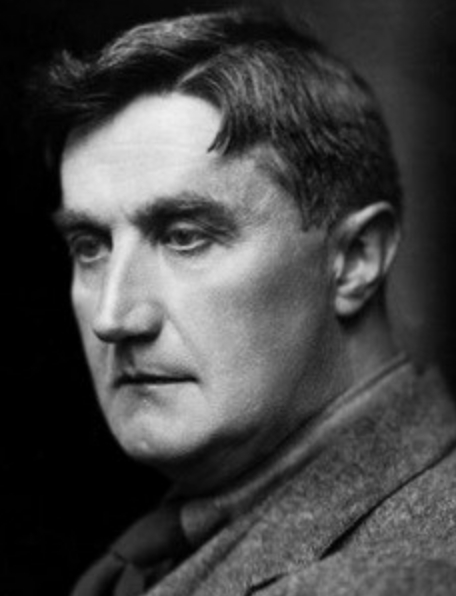

Ralph Vaughan Williams

On this date in 1872, composer Ralph Vaughan Williams was born in Down Ampney, Gloucestershire, England. He was Charles Darwin’s great-nephew. He attended the Royal College of Music from 1890 to 1892 and earned a degree in music from Trinity College at Cambridge University in 1894 and a degree in history in 1895. He later studied music with accomplished composers Max Bruch and Maurice Ravel.

Williams composed orchestras, hymns, chamber music, operas and symphonies. His work included such memorable pieces as “Fantasia on Greensleeves” (1934), “The Lark Ascending” (1914) and “Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis” (1910). He wrote nine symphonies, including “A Sea Symphony” (1910), “Pastoral Symphony” (1921) and “Symphony No. 4” (1935). He was a professor at the Royal College of Music from 1919 to 1938. Williams married Adeline Fisher in 1897 and after her death married Ursula Wood in 1953.

In her 1988 biography of her husband, Ursula Vaughan Williams wrote, “He was an atheist during his later years at Charterhouse and at Cambridge, though he later drifted into a cheerful agnosticism: he was never a professing Christian.” D. 1958.

PHOTO: Williams circa 1920.

“There is no reason why an atheist could not write a good Mass.”

— Williams, quoted in "R.V.W.: A Biography of Ralph Vaughan Williams" by Ursula Vaughan Williams (1988)

Ned Rorem

On this date in 1923, Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Ned Rorem was born in Richmond, Ind., where he was raised as a Quaker. He studied at the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools, the American Conservatory of Music, Northwestern University, the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia and the Julliard School in New York City. A hugely prolific composer, Rorem wrote operas, symphonies, chamber music, concertos and numerous vocal works.

He lived in France for nine years and In 1966 published The Paris Diary of Ned Rorem, an account of his sexuality and that of his partners, who allegedly included Leonard Bernstein, Noël Coward, John Cheever, Samuel Barber and Virgil Thomson. He also wrote extensively about music. His essays, collected in the anthologies Music From the Inside Out (1967), Music and People (1968) and Setting the Tone (1983), are generally acclaimed by critics for his prose style and revealing looks at contemporaries.

Rorem was the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship (1951), Guggenheim Fellowship (1957), National Institute of Arts and Letters Award (1968) and Pulitzer Prize for Music (1976) for his suite “Air Music: Ten Etudes of Orchestra.” Time magazine called him “the world’s best composer of art songs.” His companion of 30 years, James Holmes, an organist and choir director, died at age 59 of AIDS in 1999 at their home in New York City. Rorem died at home at age 99. (D. 2022)

PHOTO: Rorem at age 30; Library of Congress photo.

“Now that I’m closer than I was a year ago to the unknown, I’m very much an atheist and more so every day. I think we’ve invented God to give some sort of meaning to life because life doesn’t have any meaning. We’ve certainly invented money for that and we’ve invented art for that. It helps us kill time before time kills us. I’m not in despair, but I’m melancholy most of the time. But if I died today I’m not ashamed of what I’ve created.”

— Rorem, quoted in the San Francisco Chronicle (Sept. 10, 2003)

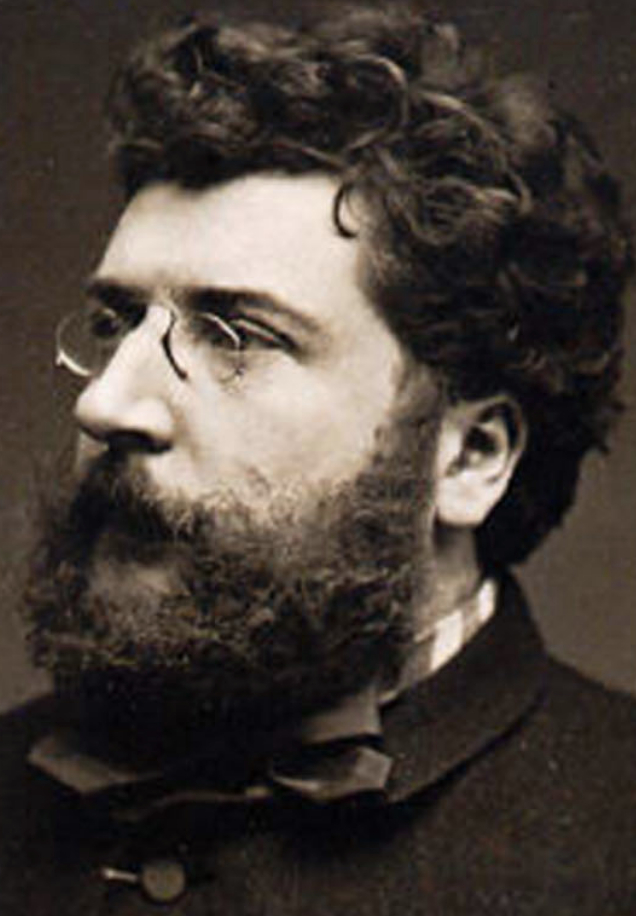

Georges Bizet

On this date in 1838, composer Georges Bizet (Alexandre César Léopold Bizet) was born in Paris. The musical prodigy entered the Paris Conservatoire at age 9. Over the next decade he won virtually every prize available, including the Prix de Rome. Bizet refused a career as a concert pianist in order to compose operas. He wrote about 30, none particularly successful, until he composed “Carmen” in 1875, based on Prosper Merimee‘s novella about a Spanish gypsy girl.

“Carmen” was controversial not only because of its humble subject matter and passionate sweep, but for the fact that the libretto was written in French and (scandalously) could be understood by the audience. Criticism and a lukewarm reception closed the play after a brief run, although the composers of Bizet’s day praised it. The dejected composer, who suffered from ill health, died of a heart attack three months later at the age of 36, never knowing “Carmen” would become the most-produced opera in history. Bizet also wrote “Jeux d’Enfants,” 12 charming piano duets.

Bizet was a rationalist. As a young man, struggling with his religious and philosophical views, he was asked to write a Mass. Preferring to write a comedy, he replied: “I don’t want to write a mass before being in a state to do it well, that is [as] a Christian. I have therefore taken a singular course to reconcile my ideas with the exigencies of Academy rules. They ask me for something religious: very well, I shall do something religious, but of the pagan religion.” (Georges Bizet: His Life and Work by Winton Dean, 1965.)

In 1869 he married Geneviève Halévy, the nervously unstable daughter of composer Fromental Halévy. Her family initially opposed the match with a “penniless, left-wing, anti-religious Bohemian.” (The Life and Times of the Great Composers by Michael Steen, 2003.) The marriage was intermittently happy and produced a son, Jacques. Bizet had fathered another son in 1862 with Marie Reiter, his father Adolphe’s housekeeper. The boy was brought up as Adolphe’s son; only on her deathbed in 1913 did Reiter reveal his true paternity.

A heavy smoker, he died at age 36 of a heart attack on his wedding anniversary on June 3, 1875.

Photo: Bizet in the year he died.

“Religion is a means of exploitation employed by the strong against the weak; religion is a cloak of ambition, injustice and vice.”

— Bizet, from "Bizet" by William Dean (1962)

Niccolo Paganini

On this date in 1782, violinist Niccolò Paganini was born In Genoa, Italy. He composed his first sonata before the age of 9 and made his first public appearance in 1793. Paginini was appointed first violinist at the Lucca Court, where his diligent application (reportedly practicing up to 15 hours a day as a youth) made him Europe’s foremost virtuoso violinist. Paganini’s acclaimed six-year world tour enthralled audiences with his legendary showmanship, made him wealthy and brought him international celebrity.

He played his own compositions, considered to be so diabolically intricate that the superstitious widely accused him of having made a pact with the devil. Yet his tender passages routinely brought his audience to tears. Paginini retired to his villa in Parma. He lived a religion-free life, refused Catholic sacraments on his deathbed and religious ritual at his burial.

Even his religious biographer, Count Conestabili, admitted Paganini’s “religious indifferentism.” (Vita de Niccolo Paganini, 1851) D. 1840

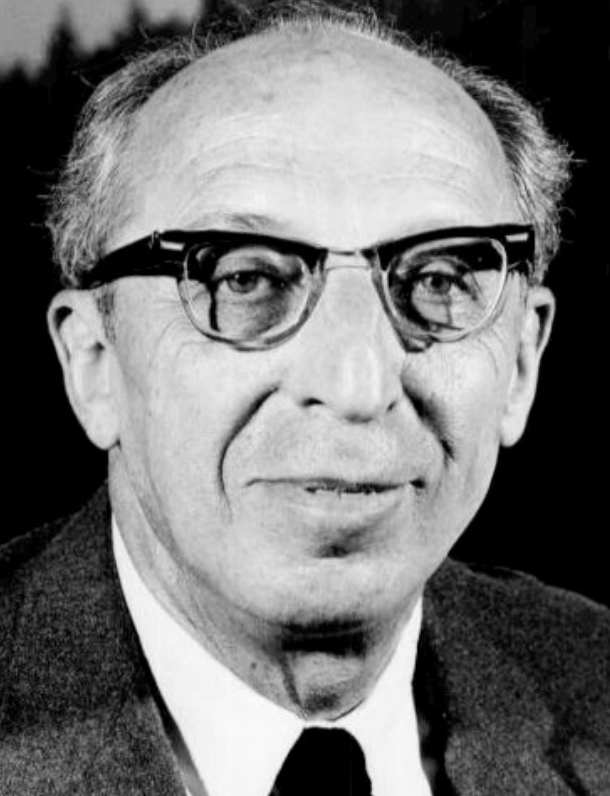

Aaron Copland

On this date in 1900, composer Aaron Copland was born in Brooklyn, N.Y., into a Conservative Jewish family of Lithuanian origins. He composed a number of ballets, including “Appalachian Spring,” “Billy the Kid” and “Rodeo,” along with “Fanfare for the Common Man,” “Third Symphony,” chamber music, vocal works, opera and film scores, about 100 works in all.

“To all appearances, and by all accounts, he was what many might call a secular humanist,” wrote Leon Botstein. “He emerged as an adult without an ongoing connection to religion.” (“Copland Reconfigured,” Aaron Copland and His World, 2005, eds. Carol Oja and Judith Tick.) His friend Leonard Bernstein would tease him by saying that he was not a a “real Jew.”

Copland, who was gay, lived and died as a nonbeliever and specified that his funeral service, if any, be “nonreligious.” He died at age 90 in North Tarrytown, N.Y. (D. 1990)

PHOTO: CBS-TV public domain photo of Copland in 1962.

“However, in adult life, although retaining strong memories of the music he heard in the synagogue and at Jewish weddings, Copland evidenced little direct connection with Judaism or Jewish culture. He was neither religious nor observant.”

— from "Copland and the Prophetic Voice" by Howard Pollack in "Aaron Copland and His World" (2005)

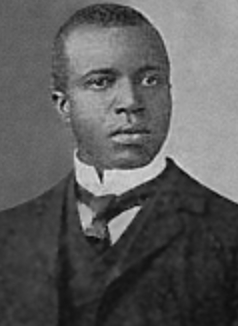

Scott Joplin

On this date in 1868, composer Scott Joplin, the “King of Ragtime,” was born in Texas. His early musical career took place in centers of entertainment, not in church. He played piano in a brothel and in a club (the famous Maple Leaf) that was shut down due to pressure from local churches, whose pastors were ashamed of the “iniquitous practices” (dancing and cards) taking place there. Ragtime was America’s first uniquely national style of music. Joplin’s 1899 “Maple Leaf Rag” became a huge hit, followed by dozens more, including “The Entertainer,” showcased in the 1974 film “The Sting,” which won the Best Picture Oscar.

In the opera Treemonisha, dealing with the fact that the African-American community was still living in ignorance, superstition, and misery, Joplin tells his audience that the way out of this condition is through education. He does not propose religion as the solution: “Ignorance is criminal.” Treemonisha, a woman who promotes education, is a leader who is more persuasive than the useless pastor in town. To the conjurer Zodzetrick, she says, “You have lived without working for many years, All by your tricks of conjury. You have caused superstition and many sad tears. You should stop, you are doing great injury.”

Revealing a freethought attitude, Joplin named the pastor “Parson Alltalk” — all he does is talk and exhort the people to be good; he is totally ineffectual, unable to see people’s real needs and, being uneducated, unable to provide leadership. The opera contains no gospel music, no hymns or religious melodies that would have been expected of such a community.

Joplin married Belle Hayden in 1899. Their baby daughter died in infancy and they soon divorced. He married Freddie Alexander in 1904 but she died 10 weeks later of complications from a cold. In 1909 after moving to New York, he married Lottie Stokes. He died on April 1, 1917, of syphilitic dementia at age 48 and was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave in Queens. It was finally given a marker in 1974. He was awarded a special Pulitzer Prize in 1976 for his contributions to music. (D. 1917)

“There is no harm in musical sounds. It matters not whether it is fast ragtime or a slow melody like ‘The Rosary.’ ”

— Joplin, quoted in "King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era" by Edward A. Berlin (1994)

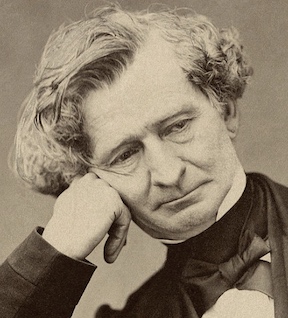

Hector Berlioz

On this date in 1803, musical composer Hector Berlioz was born in Dauphine, France. His mother was a devout Catholic. His physician father, an agnostic, expected Hector, who had a musical affinity, to follow in his footsteps. Repelled by the crude medicine of his day, he turned from medical studies to music when his cantata won a Conservatoire prize. He was awarded the Prix de Rome in 1830. The passionate composer was highly influenced by Shakespeare, writing three major works on Shakespearean themes.

He married actress Harriet Smithson. Now considered the father of French Romanticism, Berlioz was discouraged by French critics at the time, despite major compositions such as Symphonie fantastique (1830), Harold en Italie, Romeo and Juliette and overtures to King Lear and Rob Roy. In fact, his works were so original and sweeping that many regarded Berlioz as a musical lunatic. He was forced to become a music critic to support himself. Gradually, Berlioz found his recognition abroad and toured throughout the 1840s and 1850s. While not hostile toward religion, Berlioz had no religious affiliation and was widely known as an agnostic.

He died at home in Paris at age 69. (D. 1869)

PHOTO: Berlioz in 1863.

“I believe nothing.”

— From a Berlioz letter cited in G. K. Boult's "Life of Berlioz" (1903)

Ludwig van Beethoven

On this date in 1770, composer Ludwig van Beethoven was born in Bonn, Germany, into a Catholic family. After working as an assistant organist, he studied in Vienna under Haydn. Beethoven was an admirer of Goethe, who rejected Christianity in favor of a pantheistic viewpoint. When his friend Moscheles returned a manuscript to Beethoven with the words “With God’s help” on it, Beethoven reportedly wrote instead, “Man, help thyself.” (Cited in A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists by Joseph McCabe, 1920)

His biographer and friend Anton Schindler wrote that Beethoven was “inclined to Deism.” Although he received Catholic ministrations at the insistence of religious friends, Beethoven reportedly said in Latin after the priest left, “Applaud, friends; the comedy is over.” (Beethoven’s Brevier, Ludwig Noll, 1870.) In the Imperial Dictionary of Universal Biography (1857), George Macfarren described Beethoven as a “free-thinker.” (D. 1827)

“There is no record of his ever attending church service or observing the orthodoxy of his religion. He never went to confession. … Generally he viewed priests with mistrust.”

— George Marek, "Beethoven: Biography of a Genius" (1969), cited by James A. Haught in "2000 Years of Disbelief"

David Randolph

On this date in 1914, composer David Randolph (né Rosenberg) was born in New York City. He held a bachelor’s degree from the City College of New York and earned a master’s in music education from Teachers College of Columbia University. During World War II, Randolph worked for the U.S. Office of War Information. In 1947, CBS hired him to script classical radio broadcasts. He founded a madrigal group, the Randolph Singers, which performed widely and in 1948 he married Mildred Greenberg, an alto in the choir.

His sonorous baritone was known to listeners of the weekly classical music program “Music for the Connoisseur” on WNYC. The program, later called “The David Randolph Concerts,” ran for more than 30 years starting in 1946. He wrote the well-received This is Music: A Guide to the Pleasure of Listening (1964). The New York Times published a lengthy obituary in 2010 noting that Randolph’s performances of Handel’s “Messiah” (at least 170 full performances with two different choruses) were a mainstay of New York’s holiday season.

Randolph remarked at a 2009 luncheon in his honor in New York City, hosted by FFRF Co-Presidents Dan Barker and Annie Laurie Gaylor: “A couple of months ago I had the pleasure of appearing on the Freethought Radio program with Dan and Annie Laurie, and Annie Laurie said to me, ‘How can you as an atheist conduct Handel’s Messiah?’ My answer was this: Suppose Dan were engaged as an actor to play the role of Iago in Shakespeare’s ‘Othello,’ admittedly one of the most vicious and horrible people in the world. Would he be able to do it? Yes. Does he have to be vicious and horrible? No, not at all.”

“There was no such thing as ‘religious’ music, Randolph felt. … There was only music put to different uses, in different contexts,” wrote Oliver Sacks. (The Paris Review Daily, Dec. 21, 2010) “He would mention [this] when conducting his favorite Requiem Masses by Brahms, Verdi or Berlioz — all of whom, he would remind the audience, were atheists (as he himself was).

Randolph was the original music director of the Masterwork Chorus, a high-level amateur group he led through 37 seasons before stepping down in 1992. He began directing the St. Cecilia Chorus in Manhattan in 1965 (entirely secular despite the inherited name), featuring works by freethought composers. Randolph retired from the post the Sunday before his death at age 95 from complications of pneumonia and cancer. (D. 2010)

“Fortunately I was brought up in a family in which religion played almost no part whatsoever.”

— Randolph, Freethought Radio (Dec. 20, 2008)