scifi-authors

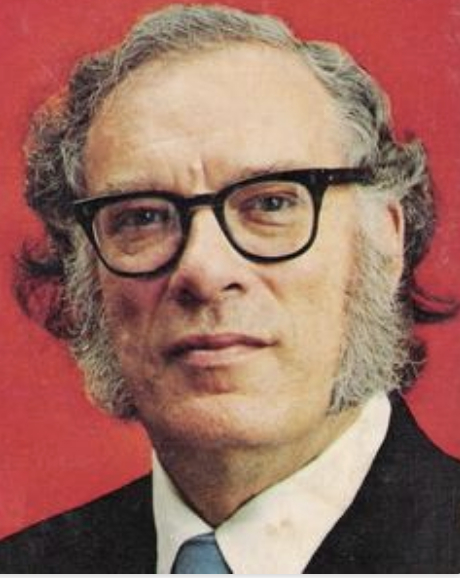

Isaac Asimov

On this day in 1920, Isaac Asimov, a self-described “second-generation freethinker” and one of the world’s most prolific authors, was born in Petrovichi, Russia. He moved with his family to Brooklyn, New York, in 1923 and became a naturalized citizen in 1928. He sold one of his earliest published short stories, “Nightfall,” in 1941, which was eventually voted the best science-fiction short story ever written, by the Science Fiction Writers of America.

Asimov graduated from Columbia University in 1939, earned his M.A. in 1941 and a Ph.D. in chemistry in 1948. He was hired by Boston University’s School of Medicine to teach biochemistry the following year. He became an associate professor of biochemistry in 1955 and professor in 1979, although he stopped teaching in 1958 to devote his life to writing.

I, Robot (1950) was the title of his first collection of short stories. Employing the “Asimovian Law of Composition,” which meant writing from nine to five, seven days a week (often closer to 6:30 a.m. to 10 p.m.), he averaged at least 12 new books a year. Asimov won five Hugos, three Nebula Awards, and his best-known “Foundation” trilogy was given a 1966 Hugo as “Best All-Time Science-Fiction Series.” Nonfiction works by Asimov were typically encyclopedic in range, such as his well-known Asimov’s Guide to the Bible (1968) and Asimov’s Annotated Paradise Lost (1974). He wrote a series of popular books on science and history, and even a guide to Shakespeare.

Asimov was an atheist: “I am Jewish in the sense that if an Arab wanted to throw a rock at a Jew, I would qualify as a target as far as he was concerned. However, I do not practice Judaism or any other religion.” (March 17, 1969 letter.) “Properly read, the Bible is the most potent force for atheism ever conceived.” (Feb. 22, 1966 letter.) He published 470 books, covering every category in the Dewey Decimal System, fiction and nonfiction.

Asimov was married twice and had a son and daughter from his first marriage. His death at age 72 from heart and kidney failure was a consequence of AIDS, a fact later revealed by his wife Janet Asimov. (D. 1992)

“Just the force of rational argument in the end cannot be withstood.”

— Asimov, solstice speech to the New Jersey Freedom From Religion Foundation (Dec. 22, 1985)

Douglas Adams

On this date in 1952, science fiction/comedy writer Douglas Noel Adams was born in Cambridge, England. He was educated at St. John’s College, Cambridge, where he graduated with a B.A. in 1974 and later earned his master’s in English literature. Adams worked as a writer and producer in radio and television.

In 1978, “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” ran as a series on BBC Radio and was published as a novel in 1979. More than 14 million copies of the cult sci-fi novel have sold worldwide, followed by sequels. The satiric novel chronicles the adventures of an alien, Ford Prefect, and his human companion, Arthur Dent, as they travel the universe looking for the meaning of life after Earth’s destruction. Adams was also an internet pioneer.

He married Jane Belson in 1991 and they had a daughter, Polly, in 1994. He was at work on a screenplay for Hitchhiker when he died unexpectedly at age 49 of a heart attack in 2001. (It was made into a movie in 2005.) Adams called himself a “committed Christian” as a teenager, who began to rethink his beliefs at age 18 after listening to the nonsense of a street preacher. He credited books by his friend Richard Dawkins, including The Selfish Gene and The Blind Watchmaker, for helping to cement his views on religion.

Dawkins used Adams’s influence to bolster arguments for nonbelief in his 2006 book The God Delusion, which he dedicated to Adams, whom he jokingly called “possibly [my] only convert” to atheism. After Adams’ death, Dawkins wrote, “Science has lost a friend, literature has lost a luminary, the mountain gorilla and the black rhino have lost a gallant defender.”

Adams’s official biography Wish You Were Here shares its name with the Pink Floyd song. Adams was friends with Pink Floyd guitarist David Gilmour. Adams chose the name for Pink Floyd’s 1994 album “The Division Bell” by picking the words from the lyrics to one of its tracks, “High Hopes.” He played guitar lefthanded and had two dozen lefthanded guitars.

He was living in Santa Barbara, Calif., where he died and was cremated. His ashes are in Highgate Cemetery East in London. In The Salmon of Doubt, a compilation of Adams’ writings published posthumously in 2002, he wrote of religion: “But it does mystify me that otherwise intelligent people take it seriously.” (D. 2001)

“If you describe yourself as ‘Atheist,’ some people will say, ‘Don’t you mean “Agnostic?’ I have to reply that I really do mean Atheist. I really do not believe that there is a god — in fact I am convinced that there is not a god (a subtle difference). I see not a shred of evidence to suggest that there is one. It’s easier to say that I am a radical Atheist, just to signal that I really mean it, have thought about it a great deal, and that it’s an opinion I hold seriously.”

— Adams interview, American Atheist (Winter 1998-99)

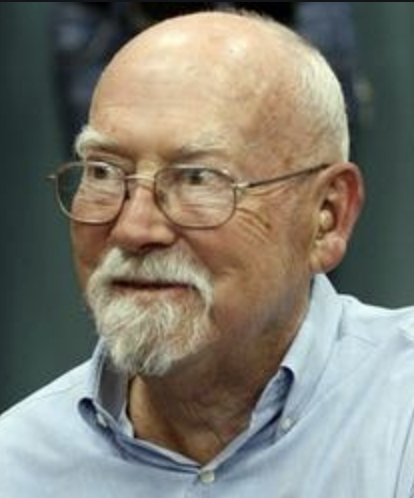

Harry Harrison

On this date in 1925, author and editor Harry Max Harrison (né Henry Maxwell Dempsey) was born in Stamford, Conn. His mother was a Russian born in Latvia and his father, of Irish descent, was born in New York state. Growing up in New York City, Harrison spent a lot of time alone, excelling in science at school and devouring science fiction books.

At age 13 he was one of the founding members of the Queens chapter of the Science Fiction League. After high school he joined the U.S. Army Air Corps, where high marks on technical aptitude tests secured him training in computers. Discharged in 1946, Harrison enrolled in the Cartoonists and Illustrators School in New York City, where he met many artists who gained prominence in the comic book industry.

Harrison became an exemplary comic book artist himself, designing hundreds of pages of comics and covers over the next few years, including “Worlds Beyond: A Magazine of Science Fiction Fantasy.”

As the “Red Scare” in the 1950s advanced, comic books became a political target, blamed for “corrupting America’s youth.” The comic book boom came to an end, forcing artists like Harrison to take up other trades. Harrison stuck with his childhood love and started writing science fiction. He was one of the main writers of the Flash Gordon comic strip in the 1950s and 1960s. One of his novels, Make Room! Make Room! (1966), was the basis of the sci-fi classic film “Soylent Green” (1973).

Some of his other prominent books (there are dozens) include The Stainless Steel Rat (1961), Bill, the Galactic Hero (1965), The Technicolor Time Machine (1967) and A Rebel in Time (1983). An entry titled “Atheist” linked to his website details how Harrison’s short story “The Streets of Ashkelon” (1962) remained unpublished for over a year because the hero was an atheist who tried to protect the inhabitants of an alien world from the influence of a Christian missionary: “The story was regarded as being too offensive for a Christian readership.”

He married Evelyn Harrison in 1950, divorcing in 1951. He married dress designer and ballet dancer Joan Merkler in 1954. They had two children, Todd and Moira, and were married until her death in 2002. He died in 2012 at age 87 in his apartment in Brighton, England. (D. 2012)

“We atheists lead happy lives, never concerned with the-dying-and-burn forever-in-hell nonsense. We know better. We enjoy happiness with our friends and neighbors and ignore all the greed and rituals that pay the parasite priests. Let them wallow in their medieval superstition while we enjoy all the wonders of our God-free universe.”

— Henry Harrison News blog, "They're Afraid of Us!" (April 23, 2011)

Pamela Sargent

On this date in 1948, science fiction writer Pamela Sargent was born to nonreligious parents in Ithaca, N.Y. Asked in 1990 who inspired her as a child, she said her grandmother did: “She’d been kind of rebellious as an adolescent herself, and managed to get herself expelled from a convent where she was a student. Apparently the nuns considered her ‘wild,’ even though she didn’t do much more than sneak out after hours to meet guys.”

Sargent earned her B.A. and M.A. from SUNY-Binghamton. Sargent is the author of many science fiction books and short stories and has edited several anthologies specializing in female and feminist science fiction. Her early books include Women of Wonder: Science Fiction Stories by Women About Women (1975), Cloned Lives (1976), Bio-Futures: Science Fiction Stories about Biological Metamorphoses (1976), Starshadows: Ten Stories (1977), The Sudden Star (1979), The Alien Upstairs (1983), Alien Child (1988), The Best of Pamela Sargent (1987) and Women of Wonder: The Contemporary Years (1995).

She continues to publish regularly as of this 2019 writing. Her novel Season of the Cats was published in 2015 and her epic historical novel Ruler of the Sky (1993) about Genghis Khan came out in a new Spanish edition in 2019.

Sargent photo by Jerry Bauer.

“Gore Vidal once wrote that, whatever most writers say, the books that influence them most are those read in childhood — before the age of twelve, say — presumably because childhood experiences are the most formative. Assuming he’s right, the most influential books for me must be Bambi, Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White, Grimm’s fairy tales, Bulfinch’s Mythology, Walter Farley horse books like The Black Stallion (I read them all), The Cloister and the Hearth and other historical novels too numerous to list, Fred Hoyle’s The Nature of the Universe, and The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan, which my mother gave me, interestingly enough. Oh, and the Bible, believe it or not, even though I was brought up as an atheist.”

— Pamela Sargent, 1990 interview with Jill Engel-Cox, NOVA Express

Bruce Sterling

On this date in 1954, science fiction writer Bruce Sterling was born in Austin, Texas. His first novel was Involution Ocean. He is among the creators of the 1980s dystopian “cyberpunk genre” of science fiction. Sterling has written about 10 novels, and also edited Mirrorshades, a 1986 anthology. He writes Catscan for SF Eye and has worked as a professor. Sterling is involved in the Viridian Design Movement and wrote the “Viridian Manifesto.”

Photo by Pablo Balbontin Arenas with permission under GNU Free Documentation.

“I don’t believe in God.”

— Sterling interview, Cybersociology magazine (July 27, 1998)

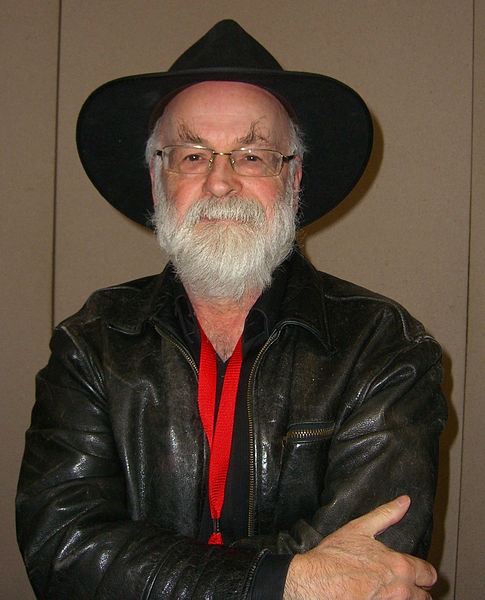

Sir Terence (Terry) Pratchett

On this date in 1948, Terence David John Pratchett was born in Buckinghamshire, England. He enjoyed reading, especially science fiction, fantasy, myth and ancient history. He has said that from a young age he was skeptical about Christianity and came to the conclusion that there was no God. He won many awards, including the Carnegie Medal for The Amazing Maurice and Educated Rodents (2001), and was knighted in 2009 for his services to literature. Several of his books have been adapted as movies for television. Pratchett’s first novel, Carpet People, a children’s fantasy, was published in 1971.

Pratchett is best known for his “Discworld” novels, a fantasy series tied together not by characters or plot but by the setting of the Discworld, a flat world sitting on the backs of four elephants standing on the back of a giant turtle swimming through space. The first book in this series, The Color of Magic, a fantasy adventure starring a hapless wizard parodying many conventions of the genre, was published in 1983, and the 38th, I Shall Wear Midnight, a coming-of-age story featuring a strong young witch battling prejudice, was published in 2010. The Discworld, like many fantasy worlds, features gods who occasionally interfere directly in events or feature as characters in some way.

Throughout his work, Pratchett questions religion in many different ways, pointing out religious hypocrisy while at the same time illustrating how different the world would be if God, or any gods, were real. The 1992 Discworld novel Small Gods shows the god Om visiting his worshipers, and being deeply dissatisfied with the direction in which his church has gone. Good Omens (1990), co-written with fellow British fantasy author Neil Gaiman, deals with Christian mythology and the biblical book of Revelation.

It begins with an angel and a demon conversing outside the Garden of Eden and questioning God’s motives regarding the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. It ends with the 10-year-old anti-Christ, Adam, contemplating the raid of a neighbor’s orchard and thinking, “There never was an apple … that wasn’t worth the trouble you got into for eating it.” Pratchett said, “I read the Old Testament all the way through when I was about 13 and was horrified.” (UK Daily Mail, June 21, 2008)

In 2007, Pratchett was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s, but continued to write and publish new books, albeit at a slower pace. He made many public statements in support of the right to die and talked openly about his Alzheimer’s experience, including his wish to take his own life before his disease was critical. He died of Alzheimer’s complications at age 66. (D. 2015)

PHOTO: by © Luigi Novi / Wikimedia Commons under CC 3.0.

“There is a rumor going around that I have found God. I think this is unlikely because I have enough difficulty finding my keys, and there is empirical evidence that they exist.”

— Pratchett, The Daily Mail (June 21, 2008)

Roger Zelazny

On this date in 1937, Roger Zelazny was born in Euclid, Ohio. Zelazny received his B.A. in English literature from Western Reserve University. He went on to study Elizabethan and Jacobean drama at Columbia, where he graduated with a master’s in English and comparative literature. Zelazny’s writing career blossomed in the early 1960s. All of his shorter works have been published in a six-volume set (The Collected Stories of Roger Zelazny) by NESFA Press (2009). The set includes an integrated biography (… And Call Me Roger) by Christopher Kovacs.

Zelazny was also famous for his novels. Perhaps the best known were the two Amber series, comprised of five novels each. Though death cut short his career, awards for his writing were impressive. They included three Nebulas (out of 14 Nebula nominations), six Hugos (out of 14 Hugo nominations), two Locus Awards, two Seiun awards, and one Prix Tour-Apollo award.

Zelazny had a fascination with mysticism and was an expert on religion and mythology. In fact, he frequently employed myth as a basis for his stories, including the seasonal death and resurrection themes that often characterized gods. Not prone to sharing details of his personal life, people speculated about what Zelazny believed in and if it was reflected in his writings.

Zelazny was married twice, first to Sharon Steberl in 1964 (divorced, no children), and then to Judith Alene Callahan in 1966, with whom he had two sons, Devin and Trent. He died at age 58 of kidney failure secondary to colorectal cancer. (D. 1995)

“I did have a strong Catholic background, but I am not a Catholic. Somewhere in the past, I believe I answered in the affirmative once for strange and complicated reasons. But I am not a member of any organized religion. If you mention my Catholic background, I hope you also mention that I became a retired Catholic at age 16. I do not consider myself a Christian.”

— "... And Call Me Roger: The Literary Life of Roger Zelazny" by Christopher S. Kovacs (2009)

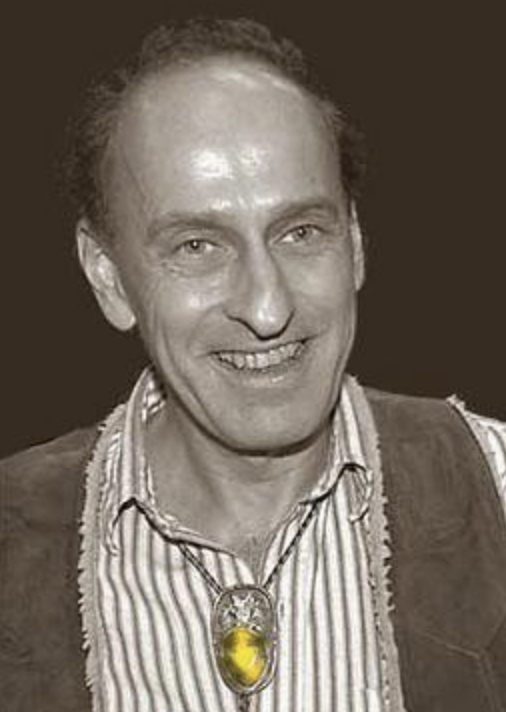

Harlan Ellison

On this date in 1934, Harlan Ellison was born in Cleveland. A prolific writer, Ellison penned 75 books and over 1,700 short stories, articles, columns and screenplays. His books and collections of short stories include I Have No Mouth & I Must Scream (1967), Approaching Oblivion (1974), Deathbird Stories (1975) and Strange Wine (1978). He worked as creative consultant for “The Twilight Zone” (1985–86) and as a conceptual consultant for “Babylon 5” (1994–99).

Ellison wrote scripts for such well-known shows as “Star Trek” — including the famous episode, “The City on the Edge of Forever” (1966) — and “The Twilight Zone.” He won numerous awards for his work, including eight Hugo Awards from 1966-86; the P.E.N. International Silver Pen in 1982 for An Edge in My Voice (1985), which was serialized in L.A. Weekly; and the Georges Melies Fantasy Film Award for Outstanding Cinematic Achievement in Science Fiction Television in 1972 and 1973.

Ellison was raised Jewish, but became critical of religion. “The people who bomb churches and synagogues, they quote the bible. The people who shoot doctors use the bible,” Harlan said during a 1997 episode of “Politically Incorrect with Bill Maher.”

In the 2008 documentary “Harlan Ellison: Dreams With Sharp Teeth,” he said, “I find nothing more ridiculous and annoying than some guy who runs a kickoff back 105 yards from the end zone and drops to his knees and thanks God. Well, that’s foolish. God didn’t do it. He did it. Because if God did that for him, you mean God was against the other team? God is that mean-spirited that he has nothing better to do on Sunday afternoon than beat the crap out of a bunch of poor football players? I don’t believe in the universe being run by that kind of a God. I go with Mark Twain.”

The New York Times noted in his obituary that Ellison was “ranked with eminent science fiction writers like Ray Bradbury and Isaac Asimov,” however Ellison prefered to call his genre of writing “speculative fiction, or simply fiction.” Ellison wrote what could be considered his own epitaph: “For a brief time I was here; and for a brief time I mattered.” (The Essential Ellison, 1987.) He died at age 84 and was survived by his fifth wife, Susan Toth. (D. 2018)

PHOTO: Ellison at the L.A. Press Club in 1986; Pip R. Lagenta photo under CC 2.0.

“I think [religion] is presumptuous and I think it is silly, because it makes you believe that you are less than what you can be. As long as you can blame everything on some unseen deity, you don’t ever have to be responsible for your own behavior.”

— Ellison, “Harlan Ellison: Dreams With Sharp Teeth” (2008)

George Orwell

On this date in 1903, writer George Orwell (né Eric Arthur Blair) was born in India. Educated at Eton College, Blair joined the Indian Imperial Police in Burma as a young man, later writing a novel, Burmese Days (1934), about it. Bumming around Europe for the experience, Blair wrote an autobiographical account, Down and Out in Paris and London (1933).

Teaching for income, he continued to write novels, including A Clergyman’s Daughter (1935), with its unflattering look at the repression of religion, Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936), and Coming Up for Air (1939). He also wrote a sympathetic nonfiction account of miners, The Road to Wigan Pier (1937). His book, Homage to Catalonia (1938), was written after he was wounded by Francoists while fighting for Loyalists in the Spanish Civil War.

When Stalinists came after Blair and his anarchist friends, his views on communism changed. While he supported a mild socialism, his masterpiece, Animal Farm (1945), skewered Stalinism: “All animals are equal but some animals are more equal than others.” Religion was satirized by the character “Moses,” a bird, who was a “spy and a tale-bearer,” who talked up “Sugarcandy Mountain, to which all animals went when they died.” Blair did commentary for the BBC during World War II.

His second masterpiece, the cautionary tale Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), unforgettably put “Newspeak” and “Big Brother” into the political lexicon and conjured up a terrifying image of totalitarianism. His views of religion became increasingly skeptical. In 1968 the four-volume Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell was published. He married Eileen O’Shaughnessy in 1936. She died in 1945 during a hysterectomy. He married Sonia Brownell the year before he died at 46 of tuberculosis. (D. 1950)

PHOTO: Orwell c. 1940

“One must choose between God and Man, and all ‘radicals’ and ‘progressives,’ from the mildest liberal to the most extreme anarchist, have in effect chosen Man.”

— Orwell, "Reflections on Gandhi," essay in the Partisan Review (1949)

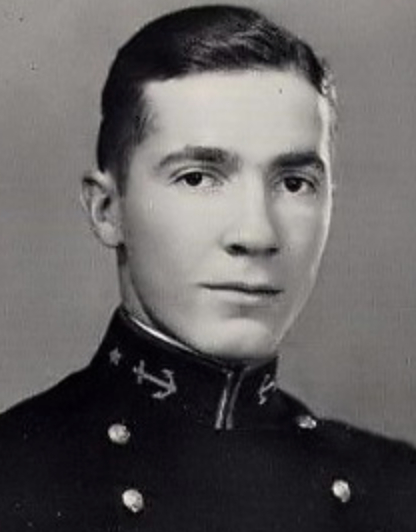

Robert A. Heinlein

On this date in 1907, Robert Anson Heinlein was born in Butler, Mo. The science fiction author is famous for his novel Stranger in a Strange Land (1961). Heinlein was one of seven children. He attended the University of Missouri and graduated from the Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1929.

Heinlein served in the Navy for five years until discharged after contracting tuberculosis. He studied at the University of California-Los Angeles and conducted research at the Navy Experimental Air Station in Philadelphia during World War II. The prolific author, who had many pseudonyms, won four Hugos for “best novel of the year” (Double Star, Starship Troopers, Stranger in a Strange Land and The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress).

He eventually published 32 novels, 59 short stories and 16 collections. Four films, two television series, several episodes of a radio series and a board game have been derived more or less directly from his work.

Heinlein wrote, “The faith in which I was brought up assured me that I was better than other people; I was saved, they were damned. … Our hymns were loaded with arrogance — self-congratulation on how cozy we were with the Almighty and what a high opinion he had of us, what hell everybody else would catch come Judgment Day.” (Peter’s Quotations: Ideas for Our Time, ed. Laurence J. Peter, 1977)

In his 1973 novel Time Enough for Love, he wrote: “History does not record anywhere at any time a religion that has any rational basis. Religion is a crutch for people.”

He married Elinor Curry in 1929 and divorced in 1930, then was married to Leslyn MacDonald from 1932-47. He was married to Virginia Gerstenfeld from 1948 until his death at age 80 in Carmel-by-the-Sea, Calif. (D. 1988)

PHOTO: Midshipman Heinlein in the 1929 U.S. Naval Academy yearbook.

“The great trouble with religion — any religion — is that a religionist, having accepted certain propositions by faith, cannot thereafter judge those propositions by evidence. One may bask at the warm fire of faith or choose to live in the bleak uncertainty of reason — but one cannot have both.”

— from Heinlein's 1982 novel "Friday" (narrated by Friday Jones)

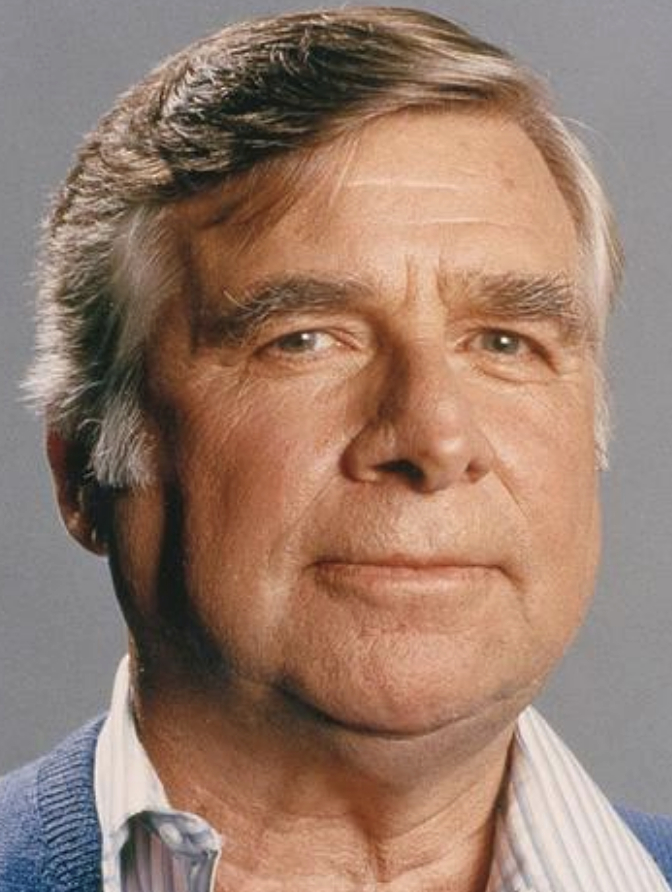

Gene Roddenberry

On this date in 1921, writer/producer Eugene Wesley Roddenberry, creator of “Star Trek,” was born in El Paso, Texas. He left for “Space, the final frontier” at age 70 from a cardiopulmonary blood clot. In college he studied pre-law and engineering and got his pilot’s license. He flew B-17s in World War II and was a commercial pilot for Pan Am. He joined the Los Angeles Police Department in 1949 and became speechwriter for Chief William H. Parker.

He started writing scripts for TV shows like “The U.S. Steel Hour,” “Goodyear Theater,” “The Kaiser Aluminum Hour,” “Four Star Theater,” “Dragnet,” “The Jane Wyman Theater” and “Naked City.” He won his first Emmy for “Have Gun, Will Travel.” “Star Trek” debuted on NBC in 1966 and ran until 1969 (79 episodes). A sequel series, “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” premiered in 1987 and ended in 1994 (176 episodes).

Roddenberry once recounted how in a script rejected by Paramount, the Enterprise met God in space. “God is a life form, and I wanted to suggest that there may have been, at one time in the human beginning, an alien entity that early man believed was God, and kept those legends. But I also wanted to suggest that it might have been as much the Devil as it was God. After all, what kind of god would throw humans out of Paradise for eating the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge?

“One of the Vulcans on board, in a very logical way, says, ‘If this is your God, he’s not very impressive. He’s got so many psychological problems; he’s so insecure. He demands worship every seven days. He goes out and creates faulty humans and then blames them for his own mistakes.’ ” (“Lost Voyages of Trek and the Next Generation” by Bill Planer, Cinemaker Press, 1992)

Paramount produced 13 “Star Trek” feature films through 2016. Roddenberry’s health had declined as he aged and he suffered strokes in 1989 and 1991 before dying of cardiac arrest at age 70 in his doctor’s office in Santa Monica, Calif. He was cremated and a secular service was held at Forest Lawn Memorial Park. (D. 1991)

“I have always been reasonably leery of religion because there are so many edicts in religion, ‘thou shalt not,’ or ‘thou shalt.’ I wanted my world of the future to be clear of that.”

— Roddenberry, quoted by his executive assistant Susan Sackett (InsideTrek.com)

Mary Godwin Shelley

On this date in 1797, Mary Godwin (later Shelley) was born in London to Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin. Her mother, the famed champion of reason and author of the seminal feminist treatise A Vindication of the Rights of Women, died 10 days after her birth. Her father, a well-known atheist and radical, had attracted the admiration of atheist and poet Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Shelley, also an admirer of Mary Wollstonecraft’s writings, met Mary in 1814. At 16 she ran away with the romantic poet, who was unhappily married to another woman and was the father of two children. His first wife’s suicide made it possible for the couple to marry in 1816. Their first two children died and their only surviving son, Percy, was born in 1819 upon their return to England. At age 19, while living in Switzerland, Mary wrote the classic horror story Frankenstein, published in 1818, in a contest between herself, Percy and Lord Byron to write a “ghost story.”

The book was immediately successful and has inspired more than 50 film adaptations. After her husband tragically drowned in 1822 in Italy, Mary returned to England, where she courted respectability on behalf of their son. She worked as a professional writer, penning short stories, travel books, essays and several other novels, including The Last Man (1826) about the gradual demise of the human race during a plague.

She died at age 53 from what her physician suspected was a brain tumor. (D. 1851)

H.G. Wells

On this date in 1866, (Herbert George) H.G. Wells was born to a working-class family in Kent, England. He received a spotty education, interrupted by several illnesses and family difficulties, and became a draper’s apprentice as a teen. Wells earned a government scholarship in 1884 to study biology under Thomas Henry Huxley at the Normal School of Science. Wells earned his bachelor of science and doctor of science degrees at the University of London.

After marrying his cousin Isabel, Wells began to supplement his teaching salary with short stories and freelance articles, then books, including The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897) and The War of the Worlds (1898). Wells created a mild scandal when he divorced Isabel to marry one of his best students, Amy Catherine Robbins. Although his second marriage was lasting and produced two sons, Wells was an unabashed advocate of free (as opposed to “indiscriminate”) love. He continued to openly have extramarital liaisons, most famously with Margaret Sanger, and a 10-year relationship with the author Rebecca West, who had one of his two out-of-wedlock children.

As a member of the socialist Fabian Society, Wells sought active change. His 100 books included nonfiction such as A Modern Utopia (1905), The Outline of History (1920), A Short History of the World (1922), The Shape of Things to Come (1933) and The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind (1932). One of his booklets was Crux Ansata, An Indictment of the Roman Catholic Church. Although Wells toyed briefly with the idea of a “divine will” in his book God the Invisible King (1917), it was a temporary aberration.

Wells used his international fame to promote his favorite causes, including the prevention of war, and was received by government officials around the world. He is best remembered as an early writer of science fiction and futurism. (D. 1946)

“Indeed Christianity passes. Passes — it has gone! It has littered the beaches of life with churches, cathedrals, shrines and crucifixes, prejudices and intolerances, like the sea urchin and starfish and empty shells and lumps of stinging jelly upon the sands here after a tide. A tidal wave out of Egypt. And it has left a multitude of little wriggling theologians and confessors and apologists hopping and burrowing in the warm nutritious sand. But in the hearts of living men, what remains of it now? Doubtful scraps of Arianism. Phrases. Sentiments. Habits.”

— Wells, "Experiment in Autobiography" (1934), cited by Ira D. Cardiff, "What Great Men Think of Religion" (1945)

Ursula K. Le Guin

On this date in 1929, author and iconoclast Ursula K. Le Guin (née Kroeber) was born in Berkeley, Calif. Her parents were the anthropologist Alfred Kroeber and the writer Theodora Kroeber. She graduated from Radcliffe College Phi Beta Kappa in 1951, earned her master’s at Columbia University in 1952 and became a Fulbright Scholar in 1953, the year she met historian Charles Le Guin aboard the Queen Mary. They had three children and lived in Oregon.

Le Guin was a lecturer or writer-in-residence at a number of universities and colleges. She wrote 20 novels and was best known for her pioneering science fiction and fantasy. She also wrote six volumes of poetry, 13 books for children, four collections of essays and many short stories.

Her many literary honors and awards included the Hugo for her 1969 gender-bending book The Left Hand of Darkness and another Hugo in 1975 for The Dispossessed, a utopian fiction. Le Guin, who said in the 1969 introduction to The Left Hand of Darkness, “I am an atheist,” accepted an Emperor Has No Clothes Award from FFRF in 2009. Read her speech here. She died at age 88 at home in Portland, Ore. (D. 2018)

PHOTO: Le Guin’s image on a U.S. Postal Service stamp issued in 2021 to honor her as part of its literary arts series.

“Let the tailors of the garments of God sit in their tailor shops and stitch away, but let them stay there in their temples, out of government, out of the schools. And we who live among real people — real, badly dressed people, people wearing rags, people wearing army uniforms, people sleeping on our streets without a blanket to cover them — let us have true charity: Let us look to our people, and work to clothe them better.”

— Le Guin, acceptance speech after receiving FFRF’s Emperor Award in Seattle (Nov. 7, 2009)

Ben Bova

On this date in 1932, science writer Ben Bova was born in Philadelphia. Raised Catholic in a working-class neighborhood, his first exposure to science on a planetarium field trip gave him hope for a better future for humanity. In a Freethought Radio interview on July 18, 2009, Bova said, “The Catholic Church teaches that faith is a gift from God, and it’s a gift I never received apparently. It always seemed kind of strange to me that we’re depending on this supernatural power and there’s no real evidence that it exists.”

Attracted to science but fearing he lacked the math skills for it led him to study journalism at Temple University in Philadelphia (1954), which landed him a job as a newspaper editor. He then worked as a technical writer for an aircraft company and as a writer for educational films at MIT. He earned a master’s in communications from the State University of New York at Albany and a Ph.D. in education in 1996 from California Coast University. His increasing renown as a writer in the 1970s brought him the role for which he would be most acclaimed, editor of Analog, the popular science fiction magazine. As editor, Bova earned five consecutive Hugo Awards (1973 to 1977) and another in 1982 as fiction editor of Omni magazine.

After his first novel (“The Star Conquerors” in 1959), Bova wrote 140 futuristic and nonfiction books. “Earth,” the 25th in The Grand Tour series, was published in 2019. He served as president of Science Fiction Writers of America and a science analyst on “CBS Morning News.” He taught science fiction at Harvard and film courses at other institutions. He received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Arthur C. Clarke Foundation (2005), was elected a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (2001) and in 2008 won the Robert A. Heinlein Award “for his outstanding body of work in the field of literature.”

Bova’s writings predicted solar power satellites, the discovery of organic chemicals in interstellar space, the space race of the 1960s, virtual reality, human cloning, stem cell therapy, the discovery of ice on the moon, electronic book publishing and the Strategic Defense Initiative (Star Wars). His novel “Mars Life” (2008) explored the clash between science, politics and religion. His 1980 article in Discover magazine, “The Creationists’ ‘Equal Time,’ ” became an inspirational classic among freethinkers.

He was president of the Barbara Bova Literary Agency, founded by his wife in 1974. They had three children. She died in 2009 of cancer in Naples, Florida, where he also died at age 88. (D. 2020)

PHOTO: Bova in 1974; photo by Dd-B under CC 3.0.

“When I started understanding how science works, it occurred to me that there just is no evidence that there is a God.”

— Bova interview on Freethought Radio (July 18, 2009)

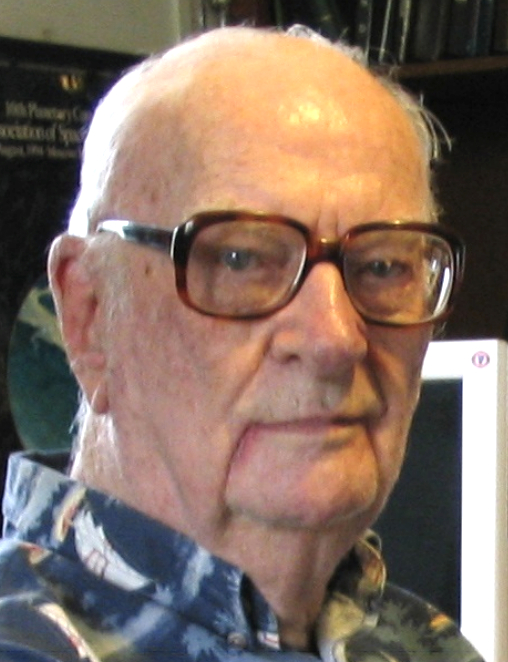

Arthur C. Clarke

On this date in 1917, science fiction writer and inventor Arthur C. Clarke was born in Minehead, Somerset, England. A stargazer as a boy, he could not afford to attend university. He became a radar specialist for the Royal Air Force during World War II. A lifelong nonbeliever, he refused to accept the “Church of England” affiliation put on his dogtag by the RAF and insisted they change it to “pantheist.” Clarke earned a degree in math and physics in 1948 at King’s College, London. He was the first to propose, in a technical paper in 1945, that geostationary satellites could make telecommunication relays, which later won him the 1982 Marconi International Fellowship and many other honors.

After selling science fiction throughout the 1940s, Clarke was writing full-time by 1951. In 1954 he suggested satellite applications for weather forecasting to the U.S. Weather Bureau. He turned from the stars to underwater exploration, concentrating on the coast of Sri Lanka, where he moved in 1956.

When Clarke was 36 he married Marilyn Mayfield, a 22-year-old American divorcee with a young son. They separated after six months, although the divorce was not finalized until 1964. He never remarried but was intimate with a Sri Lankan man, Leslie Ekanayake, who died in 1977. They were eventually buried together. Clarke’s New York Times obituary noted that journalists who asked if Clarke was gay were told, “No, merely mildly cheerful.”

His most famous work was the screenplay, co-written with Stanley Kubrick, for the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. The script was nominated for an Oscar. Clarke served as chair of the British Interplanetary Society. His TV programs included “Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World” (1981) and “Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers” (1984). He co-broadcast Apollo 11, 12 and 15 missions with Walter Cronkite and CBS News. He was wheelchair-bound starting in 1988 with post-polio syndrome.

In 2000 Clarke was knighted. Before his death at age 90, he left instructions about his funeral: “Absolutely no religious rites of any kind, relating to any religious faith, should be associated with my funeral.” He told the London Times in August 1992 that he was “an aggressive agnostic.” In 1999 he told Free Inquiry magazine, “One of the great tragedies of mankind is that morality has been hijacked by religion.” (D. 2008)

“Religion is the most malevolent of all mind viruses. We should get rid of it as quick as we can.”

— Clarke interview with Popular Science magazine (Aug. 1, 2004)