writer

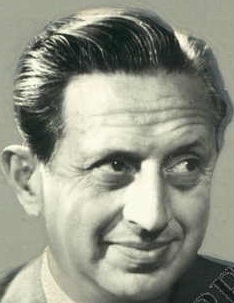

E.M. Forster

On this date in 1879, English writer Edward Morgan Forster was born in London to a wealthy family. His architect father died of tuberculosis before his second birthday. He inherited £8,000 in trust (about $1.3 million in 2017 dollars) in 1887 from his great-aunt, which enabled him to support himself by writing after attending Kings College-Cambridge.

Forster, who was gay, wrote all six of his novels while living with his mother in Surrey. They traveled widely together. As a conscientious objector in World War I, he served as a searcher of missing military members for the British Red Cross in Egypt.

His most well-known novels are A Room With a View (1908), Howards End (1910), Maurice (1913-14) and A Passage to India (1924). All four have been made into major motion pictures. A television adaptation of Howards End first aired on the cable network Starz in 2018 and premiered as a four-episode series on “Masterpiece” on PBS in January 2020. He also wrote short stories, travel pieces, scripts, essays, biographies and the libretto for Benjamin Britten’s opera “Billy Budd,” based on Herman Melville‘s novel.

In the 1930s and 1940s he worked as a broadcaster on BBC Radio and was associated with the Union of Ethical Societies. Forster called himself a humanist and was president of the Cambridge Humanists from 1959 to his death. He was a vice president of the Ethical Union in the 1950s and a member of the Advisory Council of Humanists UK from its foundation in 1963.

“A humanist has four leading characteristics — curiosity, a free mind, belief in good taste, and belief in the human race,” Forster wrote in “George and Gide,” an essay in the collection Two Cheers for Democracy (1951).

Forster had a long relationship with Robert Buckingham, a policeman 23 years his junior, with the acquiescence of Buckingham’s wife May, who came to accept that her husband was romantically involved with Forster, perhaps influenced by a gift of £10,000. He died of a stroke at age 91 at the Buckinghams’ home. His ashes, mingled with those of Buckingham, were later scattered in the rose garden of Coventry’s crematorium. (D. 1970)

PHOTO: Forster in 1938; photo by Howard Coster/National Portrait Gallery under CC 3.0.

“I do not believe in Belief.”

“There lies at the back of every creed something terrible and hard for which the worshipper may one day be required to suffer.”

— Forster's essay "What I Believe," The Nation magazine (July 21, 1938)

Marie-Henri Beyle (Stendhal)

On this date in 1783, Marie-Henri Beyle, a French writer better known by his pen name Stendhal, was born in Grenoble. Stendhal’s mother fell ill and passed away in 1790 when he was only 7. His mother was a nurturing influence and losing her meant the loss of a vital buffer between him and his father, who seemed to lack imagination or any of the same interests as his son. His father had other individuals help care for Stendhal, including a Jesuit tutor who prevented him from gaining a sense of independence by blocking him from achieving important personal goals such as learning how to swim. The tutor belittled and dissuaded him by insisting he would drown if he tried. Such events resulted in his loss of faith in religion.

Stendhal’s quest for personal autonomy was a motivating factor in his journey toward becoming one of the most original and complex writers of his time. He is best known for his critical analysis of consciousness among his characters. His writing communicates radical ideas on romanticism and realism, two concepts that tend to be seen as mutually exclusive. The coexistence of such principles is best represented through his 1830 work Le Rouge et le Noir (The Red and the Black).

In that novel, Stendhal stated that “the idea which tyrants find most useful is the idea of God.” He also published a collection of stories known as the Italian Chronicles, written in the 1830s. One chronicle discussed the issues of female emancipation and the relationship of women to the institutions of marriage and the church. He once wrote that “Popery and the lack of liberty [are] the source of all crimes.” D. 1842.

"All religions are founded on the fear of the many and the cleverness of the few."

— Stendhal, cited in "On the Mind and Freedom" by Elliot Murphy (2011)

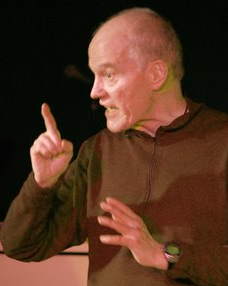

Jason Aaron

On this date in 1973, comic book writer Jason Aaron was born in Jasper, Ala., into a Southern Baptist household. He would later quip that he was Jasper’s most notable personage after George “Goober” Lindsey of “The Andy Griffith Show” and mixed martial arts fighter Eric “Butterbean” Esch.

“You grow up with religion and pork and college football, and that’s all you know for most of your life. I still love two of those things. So I grew up with faith and religion as a big part of my life, until I got to be 19 or 20 in college and just got to a point where it didn’t make sense for me anymore, and I didn’t buy into it.” (War Rocket Ajax podcast #138, Dec. 3, 2012)

Fascinated as a child by comics, he knew what he wanted to do when he grew up. He entered and won a Marvel Comics talent search contest in 2001 with an eight-page story script, which was published in Wolverine #175 (June 2002). It would be four years before he got another one published. Aaron earned a B.A. in English from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, then worked at a variety of menial or unfulfilling jobs while writing DVD and film reviews.

He broke out as a writer with “The Other Side” (2006), a five-issue series with a Vietnam War theme that was nominated for an Eisner Award for Best Miniseries. The first of 60 issues of “Scalped,” a series with artist R. M. Guéra set on a fictional South Dakota Lakota Indian reservation, was published in 2007. The day Aaron got the call it was green-lighted was the day before his wedding. He and his wife had a son, Dashiell (after novelist Dashiell Hammett), before divorcing.

Another crime novelist, James Ellroy, would later give Aaron one of the best pieces of advice he ever got: “Don’t write the shit you know, write the shit you want to read.”(Comic Book Resources online, April 8, 2011) After four issues of “Wolverine” in 2007, Aaron returned to the character with the series “Wolverine: Weapon X,” launched to coincide with the feature film “X-Men Origins: Wolverine.” He moved to Kansas City the day after the film’s premiere.

The writing continued with a “Wolverine” relaunch (2010), another of “The Incredible Hulk” (2011) and “Thor: God of Thunder” in 2012. The Thor character’s comic book history goes back to 1962. (It was announced in 2019 that Aaron’s Thor storyline was the basis for “Thor: Love and Thunder,” directed by Taika Waititi with Natalie Portman as Jane Foster/Mighty Thor.) It opened in theaters in July 2022.

He was part of the 2015 Marvel relaunch of “Star Wars” that was the best-selling American comic book in over 20 years. As of this writing, he is the current writer on Marvel’s flagship “Avengers” and its spinoff “Avengers Forever.” His critically acclaimed “Southern Bastards” series (2014 debut) received numerous nominations and awards.

PHOTO: Aaron in 2017; Stephanie Manning Photography under CC 4.0.

“I've been an atheist for many years, but I've remained fascinated by religion. If anything, I've become more fascinated by religion and faith after I lost mine.”

— War Rocket Ajax podcast #138 (Dec. 3, 2012)

Barry Duke

On this date in 1947, journalist/editor and gay rights activist Barry Duke was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, the eldest child of middle-class parents Sybil and Abe Duke. He grew up in two small towns, and from an early age showed “a strong antipathy toward religion, especially the Calvinist form of Christianity that was used to justify the country’s horrific persecution of people of color during the Apartheid era,” Duke commented in 2022.

He was expelled from the first high school he attended for condemning racial injustices, refusing to sing the national anthem and for sharing anti-religious publications with classmates. He started working as a newspaper journalist in his late teens and several years later landed a job with The Star, a leading daily.

Duke’s left-leaning, anti-Apartheid activism, coupled with censorship battles, led to him being declared a “dangerous undesirable.” Alerted that an arrest warrant was being issued, he left South Africa in 1973 for the UK, where he was granted asylum. A militant atheist, he joined the National Secular Society and was a co-founder in 1979 of the Gay Humanist Group, which changed its name to the Gay and Lesbian Humanist Association in 1987.

He started writing in 1974 for The Freethinker, the venerable publication founded by G.W. Foote in 1881, and rose to editor in 1997. He held the position until January 2022, when differences with the editorial board led to his departure. He continued his decade-long writing and editing association with the Pink Humanist and started writing on OnlySky, a secular platform that launched in 2020.

In 2017 Duke was the recipient of a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Secular Society for his “spirited opposition to religious intolerance and irrationality.” He married Marcus Robinson, his longtime partner, in 2017 in Gibraltar and they live in Benidorm, a town along Spain’s seaside Costa Blanca.

“Since [1950s John Birch Society claims], War on Christmas reports have simply become a silly festive season tradition, generating more mirth than fury. All are intended to reinforce the belief of Christian fundamentalists that they really are being persecuted by a coalition of atheists, secularists, freethinkers, abortionists – and those who identify as LGBTQ. Seriously!”

— "And so it begins … the 'war' on Christmas 2021" (The Freethinker, Nov. 25, 2021)

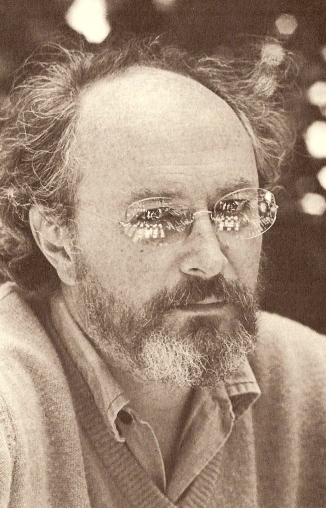

Michael Martin

On this date in 1932, renowned American philosopher and teacher Michael Martin was born in Cincinnati, Ohio. Martin was a respected academic promoter of atheism, penning several books examining the case against the existence of God.

Martin served with the U.S. Marine Corps in the Korean War before graduating from Arizona State University in 1956 with a degree in business administration. He earned a master’s degree in philosophy in 1958 from the University of Arizona and a Ph.D. in philosophy from Harvard University in 1962. That year, Martin began his teaching career at the University of Colorado as an assistant professor, joining the staff at Boston University in 1965, where he was a professor of philosophy until retiring.

The focal point of Martin’s research and writing was always the philosophy of religion and the defense of atheism. His best-known book was Atheism: A Philosophical Justification (1989), considered by some as one of the most analytical arguments against God’s existence. In its introduction he writes, “The aim of this book is not to make atheism a popular belief or even to overcome its invisibility. My object is not utopian. It is merely to provide good reasons for being an atheist. … My object is to show that atheism is a rational position and that belief in God is not. I am quite aware that atheistic beliefs are not always based on reason. My claim is that they should be.”

Martin wrote and edited several other books, including The Case Against Christianity (1991), Atheism, Morality, and Meaning (2002), The Impossibility of God (2003), The Improbability of God (2006) and The Cambridge Companion to Atheism (2006), along with numerous articles on atheism. He also engaged in a number of debates with Christian apologists. His philosophical interests extended to social science and law.

Martin was married to Jane Roland Martin, who spent much of her career as a philosophy professor at the University of Massachusetts-Boston focusing on education, gender and feminism. They married in 1962 and had two sons, Timothy and Thomas, and five grandchildren. (D. 2015)

"Since experiences of God are good grounds for the existence of God, are not experiences of the absence of God good grounds for the nonexistence of God?"

— Michael Martin, "Atheism: A Philosophical Justification" (1989)

Georg Brandes

On this date in 1842, Danish intellectual Georg Morris Cohen Brandes was born into a nonobservant Jewish family in Copenhagen, the elder brother of freethinkers Ernst and Carl Edvard Brandes. He studied jurisprudence at the University of Copenhagen before switching to philosophy and aesthetics.

He traveled through Europe from 1865-71 to acquaint himself with the condition of literature in academia. He published Aesthetic Studies (1868), a series of brief monographs on Danish poets, followed in 1870 by The French Aesthetics of the Present Day, dealing chiefly with Hippolyte Taine’s Criticisms and Portraits and a translation of The Subjection of Women by John Stuart Mill. His aesthetics lectures at the University of Copenhagen started attracting large audiences but he was refused a professorship due to his atheism and his “Modern Breakthrough” theory of the principles of a new realism and naturalism in literature being seen as too radical.

He published the six-volume Main Currents in Nineteenth-Century Literature starting in 1906. It was among the 100 best books for education selected in 1929 by historian Will Durant. His last years were dedicated to anti-religious polemic. He argued against the historicity of Jesus and published Sagnet om Jesus, which was translated as Jesus: A Myth in 1926. He died at age 85 in 1927.

“Brandes challenged Kierkegaard’s insistence on the centrality of religion on human life by promoting a secular interpretation of his works, stripped of their religious context.”

— "Kierkegaard's Influence on Literature, Criticism and Art: Denmark," ed. Jon Stewart (2013)

Alice Greczyn

On this date in 1986, actress/writer Alice Hannah Meiqui Greczyn was born in Walnut Creek, Calif., to Jane and Ted Greczyn, the eldest of their five children. Her parents met at the University of California-Berkeley, where her dad was a campus police officer and her mother was a student. Both were very religious and raised the children as “Holy Roller-style” Pentecostals.

Church services were “very emotive, very falling to the floor, being ‘slain in the spirit,’ rolling around, shaking, praying in tongues, prophesying, massive outpours of laughter and crying,” Greczyn recalled. (The Graceful Atheist podcast, March 9, 2021)

Her parents had served as missionaries in Thailand and Nepal before her dad took the pastorship at a small Foursquare Gospel Church congregation in Rockford, Ill. Greczyn (pronounced Gretchen) and her siblings were home-schooled, not primarily for religious reasons but because their college-educated mother enjoyed teaching and the children’s company. The regimen was “well-rounded” compared to other home-schooling she was familiar with, Greczyn said.

The family moved around a lot and was living in Longmont, Colo., when Greczyn was attending a community college and modeling in the Denver area. Her modeling connections led to an offer to relocate to Los Angeles, so she abandoned plans to become a missionary nurse, and with her parents’ support a month shy of turning 17, moved from the church’s “purity culture” to L.A., “the American epicenter of hedonism.” (FFRF’s “Ask an Atheist,” Feb. 17, 2021)

How wide the gulf was became apparent when she was cast as Laura in a stage production of “The Glass Menagerie,” which required her to kiss an actor. She had never dated and the kiss made her feel dirty. “I felt sick to my stomach, just wretched.”

Greczyn started her onscreen career in the 2004 movies “Sleepover” and “Fat Albert,” followed by roles in “The Dukes of Hazzard” (2005), “Shrooms” (2007) and “Sex Drive” (2008). She was busy with episodic and recurring TV roles, including Sage Lund in “Lincoln Heights” (2007-09) and most famously as Madeline “Mads” Rybak in “The Lying Game” (2011-13, available online at CW Seed). She played Emma Randall on 11 episodes of “The Young and the Restless” in 2015.

From age 17 to about 21, she lived as a “progressive Christian” and called herself “a follower of Christ” but not a Christian. Escaping from a supposedly “God-led” marriage betrothal “was the beginning of my departure from Christianity,” she said, calling it one of “these little dominos adding up” that were tipping over and leading her away from religion. She had sex for the first time and felt “totally fine” afterward.

Recurring panic attacks from what she perceived to be religious trauma led her to seek help from a secular therapist, and she continued for three years. She read Leaving the Fold by Marlene Winell, who described her 1993 book as a tool for people recovering from religious indoctrination, particularly Christian fundamentalism. She started a website — daretodoubt.org — in 2019 as “a resource hub for people detaching from belief systems they come to find harmful.” That year she wrote, “I claim a disbelief in God. I do not know if he, she, they, or it is real. I do know that I don’t believe so.”

Her book Wayward: A Memoir of Spiritual Warfare and Sexual Purity was published in 2021. To Greczyn, it’s “a coming-of-age story [that] takes place within a Christian subculture that teaches children to be martyrs and women to be silent.” To what extent had she felt discounted? “I forgave myself for being female,” she wrote in Wayward.

“Unlike a lot of other memoir writers in my genre, my family and I are not estranged. I’m still very much in touch with them and very close to them.” … There’s so much love between my family and I, and despite how difficult it’s been at times, they’ve been very supportive.” (The Graceful Atheist podcast, March 9, 2021)

Watch her interview on FFRF’s TV talk show “Freethought Matters” on April 22, 2021.

PHOTO: Greczyn at the 9th Annual Young Hollywood Awards in 2007; photo by s_bukley / Shutterstock.com

“When I completely lost my faith, I was 21. That’s when I became an atheist. I gave God a test and she failed.”

— Greczyn, with tongue in cheek on FFRF's "Ask an Atheist: Dare To Doubt" (Feb. 17, 2021)

Julian Scheer

On this date in 1926, Julian Weisel Scheer, who kept God off a plaque left on the moon in 1969, was born in Richmond, Va., to Hilda (Knopf) and George Scheer. He served in the U.S. Merchant Marine during World War II and after the war entered the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, graduating in 1950 with a degree in journalism and communications.

After working for a decade as a Charlotte News reporter, Scheer started working as a consultant for NASA at the end of the Mercury program in 1962 to create an organizational framework for NASA’s public relations efforts. In early 1963 he became NASA’s assistant administrator for public affairs. He strived to make the public more aware of the program while making flight technicians and astronauts more available for interviews. “The program was really a battle in the Cold War, and Julian Scheer was one of its generals,” astronaut Frank Borman later said. (Washington Post, Sept. 3, 2001)

In preparation for the historic Apollo 11 mission in July 1969 with commander Neil Armstrong, command module pilot Michael Collins and lunar module pilot Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, Scheer helped craft the message on a plaque that would be attached to a leg of the lunar module’s descent stage, which would land and remain in an area of the moon called the Sea of Tranquility.

Scheer drafted the text for the plaque as a member of NASA’s Committee on Symbolic Activities for the First Lunar Landing. It said: “HERE MEN FROM THE PLANET EARTH FIRST SET FOOT UPON THE MOON. JULY 1969, A.D. WE CAME IN PEACE FOR ALL MANKIND. President Nixon’s and the astronauts’ names and signatures were under the statement.

According to several accounts, including Scheer’s, Nixon wanted God mentioned. Rocket Men: The Epic Story of the First Men on the Moon by Craig Nelson (2009), recounts Scheer telling Nixon aide Peter Flanigan at the White House in early June that not everyone worships the same god after Flanigan tried to insert “under God” after “We came in peace,” with Nixon initialing his approval of the change.

That flew in the face of Scheer’s wish that the plaque should make a universal statement: “Peter [Scheer said], there is no universal god.” Flanigan: “Dammit, Julian, the president wants that change. The president is big on God. … Billy Graham is here nearly every Sunday. The president wants God on the plaque!”

Scheer, in a 1989 column he wrote for the Orlando Sentinel, said NASA administrator Thomas Paine asked him on the way back from the White House what he was going to do. “The plaque has been put on the spacecraft and checked out,” Scheer replied. “I guess the answer is nothing.” Paine answered, “I didn’t hear that.”

William Safire, a speechwriter for Nixon and Vice President Spiro Agnew at the time, later wrote in his New York Times column (July 17, 1989) about reviewing the inscription submitted by NASA: “We left ‘July 1969 A.D.’ intact because it was a shrewd way of sneaking God in [certainly not NASA’s intent]: the use of the initials for anno Domini, ‘in the year of our Lord,’ would tell space travelers eons hence that earthlings in 1969 had a religious bent; piously, we made sure that a Bible with both Testaments was included in the spacecraft’s cargo.” Safire also suggested “came in peace” should replace the original “come” and it was.

About six months earlier, on Dec. 24, 1968, the Apollo 8 crew (Bill Anders, Jim Lovell and Frank Borman) had read verses 1-10 from the Book of Genesis that were broadcast back to Earth while orbiting the moon. Scheer wasn’t involved with writing the text of what the astronauts read (drafted by Borman’s journalist friend Joe Laitin and his wife Christine). Scheer slyly told a Japanese journalist staying at a Houston hotel who was looking for the transcript: “Open the drawer of the table next to your bed. In it you will find a book. Turn to the first page. The words you are looking for are there.” (Chasing the Moon: The People, the Politics, and the Promise That Launched America Into the Space Age by Alan Andres and Robert Stone.) The book was a companion to the 2019 three-episode PBS “American Experience” documentary. The mission’s religious intrusion was later upheld by the 5th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, with the Supreme Court declining to take the case.

After the successful Apollo 11 mission, Scheer was awarded NASA’s highest award, the Distinguished Service Medal, and led the crew on tours around the world. He left NASA in 1971 to manage the campaign for Terry Sanford (D-N.C) for the presidency but remained a consultant to the space program and was a trustee of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum. He worked for a Washington-based communications consulting firm until 1976, when he became a vice president running the Washington offices of LTV Corp., whose holdings include steel mills.He retired from LTV in 1992 and returned to his consulting firm. He wrote several books, including Light of the Captured Moon for children.

He married Virginia Williams and they had three children before divorcing. After his death at age 75 of a heart attack, he was survived by his wife of 36 years, the former Suzann Huggan, with whom he had a daughter. D. 2001.

SCHEER: “What about the people on earth who do not worship our God, Buddhists, Muslims and …”

FLANIGAN: “Damn it, Julian, the president is big on God!”— "What About God/NASA Ignored Nixon's Order" by Julian Scheer, Orlando Sentinel (July 20, 1989)

Edna St. Vincent Millay (Quote)

“There is no God.

But it does not matter.

Man is enough.""A job, something at which you must work for a few hours every day; an assurance that you will have at least one meal a day for at least the next week; an opportunity to visit all the countries of the world, to acquaint yourself with the customs and their culture; freedom in religion, or freedom from all religions, as you prefer; an assurance that no door is closed to you, that you may climb as high as you can build your ladder."

— Poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, born Feb. 22, 1892 (D. 1950), "Conversation at Midnight," 1937. (She used the term "God" fairly freely in her writings, evincing some type of vague deism, except for this extract.) SECOND QUOTE: Millay, to poet and friend Arthur Ficke, when asked to name "five requisites for the happiness of the human race." ("The Poet and Her Book: A Biography of Edna St. Vincent Millay" by Jean Gould,1969)

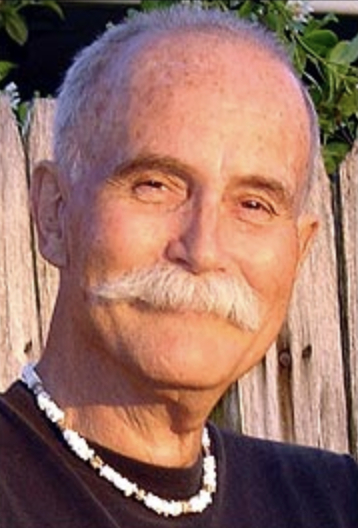

Peter De Vries

On this date in 1910, satirical novelist Peter De Vries was born in Chicago to Dutch immigrant parents who were devout Christian Reformed Church members. He attended elementary and secondary church schools. His father envisioned his son’s future as a clergyman and convinced him to enroll at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Mich., where he instead studied English and played basketball.

After graduation he returned to Chicago and sold candy on a vending-machine route, worked for a small newspaper, acted on the radio and in 1938 joined Poetry magazine, first as an associate editor, then as co-editor. He met his soon-to-be wife, Katinka Loeser, in 1943 when she won an award from the magazine. They would have four children.

That was also the year he joined the New Yorker, working with James Thurber, Robert Benchley, S.J. Perelman and Dorothy Parker. De Vries’ specialty was writing cartoon captions. He was so adept at linking verbal pith to illustrations that many New Yorker cartoons started in reverse, with images commissioned to match his captions. His 1954 novel The Tunnel of Love, later a Broadway play and a movie starring Doris Day, featured a character with talents similar to De Vries’.

De Vries wrote prolifically: short stories, reviews, poetry, essays, plays, novellas and 23 novels. “De Vries was one of the United States’ funniest writers, but never remotely the most successful. He was extraordinarily inventive, a superb maker of plots, but he wrote in an era when linguistic virtuosity and verbal comedy were increasingly undervalued.” (The Independent, Oct. 3, 1993)

To philosopher Daniel Dennett, he was “probably the funniest writer on religion ever.” Novelist Kingsley Amis wrote in 1956 that De Vries was “the funniest serious writer to be found either side of the Atlantic.” Calvin College professor James Bratt called De Vries “a secular Jeremiah, a renegade CRC [Christian Reformed Church] missionary to the smart set.”

He’d grown up forbidden to watch movies, dance or play cards. As De Vries put it, “We were the elect, and the elect are barred from everything, you know, except heaven.” (The American Interest magazine, March 1, 2010) Journalist Jonathan Hiskes, who also grew up in Chicago in the Reformed Church, writing in the journal Image, Issue 83: “Almost nobody spoke of De Vries when I was growing up. If anyone even mentioned him, they dismissed him as ‘that atheist writer.’ ”

Hiskes added: “Where Calvinists are reverent in matters of religion and silent in matters of sex, De Vries was the opposite.” Don Wanderhop, De Vries’ protagonist in The Blood of the Lamb (1961), tells a girlfriend: “Sometimes I think this leg is the most beautiful thing in the world, and sometimes the other. I suppose the truth lies somewhere in between.” He introduces another character with “She was about twenty-five, and naked except for a green skirt and sweater, heavy brown tweed coat, shoes, stockings …”

The Blood of the Lamb is autobiographical and is his darkest, most poignant novel. It ends with the death of Wanderhop’s young daughter. De Vries published it a year after his daughter Emily died of leukemia at age 10. In its climactic scene, Wanderhop rages at a god who lets children suffer and die: “How I hate this world. … I would like to dismantle the universe star by star, like a treeful of rotten fruit.”

De Vries was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1983, the year Slouching Towards Kalamazoo was published. He died at age 83 in Norwalk, Conn., and was buried alongside his wife and daughter in Westport, Conn. His tombstone says, “Dying is hard, but comedy is harder.” (D. 1993)

"What baffles me is the comfort people find in the idea that somebody dealt this mess. Blind and meaningless chance seems to me so much more congenial — or at least less horrible. Prove to me that there is a God and I will really begin to despair."

"It is the final proof of God's omnipotence that he need not exist in order to save us."

— First quote: Said by "militant atheist" Stein, who has a child in the cancer ward in "The Blood of the Lamb" (1961). Second quote: Said by the Rev. Andrew Mackerel of the People's Liberal Church in "The Mackerel Plaza" (1958)

Michel de Montaigne

On this date in 1533, essayist Michel Eyquem de Montaigne was born near Bordeaux, France. His mother’s Spanish-Portuguese family had converted from Judaism to Protestantism and immigrated to France during the Spanish Inquisition. His Catholic father, a well-to-do merchant, came from a titled family. Tutored by his father, Montaigne spoke Latin fluently by age 6. He completed his studies at the College de Guyenne at 13, then studied law, replacing his father as councilor of the Bordeaux court in 1555.

After serving for 15 years, he resigned to commence writing essays, a term he coined himself from the French word “essai” (attempt), and which he defined as “the dialogue of the mind with itself.” At his father’s request, he translated Spanish theologian Raimond Sebond’s 1,000-page book on natural theology, which averred religious claims could be proved by scientific logic. When the first two volumes of his Essays were published in 1580, Montaigne’s longest essay was “Apology for Raimond Sebond,” which countered Sebond’s claim, arguing religion could only be believed by faith.

Montaigne’s observations on religion in Essays include: “How many things served us yesterday for articles of faith, which today are fables to us?” “Philosophy is doubt.” “To know much is often the cause of doubting more.” “Nothing is so firmly believed as what we least know.” During the bloody religious wars between French Catholics and Protestant Huguenots, Montaigne played the role of intermediary between King Henry III and the Huguenot Henry of Navarre.

Montaigne was jailed briefly, first by the Protestants, then by the Catholics. He campaigned in 1598 for the issuance of the Edict of Nantes by King Henry IV to restore religious toleration. Montaigne was mayor of Bordeaux for four years and completed his third volume of Essays in 1588. Essays were put on the Catholic Church’s notorious index of condemned writings in 1676.

Freethought historian J.M. Robertson (A Short History of Freethought,1957) considered Montaigne a humanistic deist who significantly rejected “the great superstition of the age, the belief in witchcraft.” Montaigne’s motto was Que sais-je? (What do I know?) D. 1592.

"Man is certainly stark mad. He cannot make a flea, and yet he will be making gods by the dozen."

— Michel de Montaigne, "Essays" (1580)

John Rechy

On this date in 1931, American writer and critic John Francisco Rechy was born in El Paso, Texas, to Guadalupe (née Flores) and Roberto Sixto Rechy. He earned a B.A. in English from Texas Western College (now the University of Texas at El Paso), where he edited the school paper. He enlisted in the U.S. Army but was granted an early release to enroll at Columbia University.

Rechy’s novels and essays often documented gay culture. His first novel, City of Night (1963), a largely autobiographical account of the travels of a young hustler, included a description of the Cooper Do-nuts Riot of 1959 in L.A. when LGBTQ community members pelted police with coffee cups and doughnuts to protest ongoing harassment of gays. City of Night became an international best-seller. The Doors incorporated the title in their 1971 song “L.A. Woman.” Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side” paid homage to its transgender street hustlers.

Rechy has written a dozen novels to date and has had essays and reviews published in The Nation, The New York Review of Books, Los Angeles Times, L.A. Weekly, The Village Voice, The New York Times, Evergreen Review and Saturday Review. He has taught creative writing at Occidental College, the University of California-Los Angeles and the University of Southern California.

Rechy was the first novelist to receive PEN-USA-West’s Lifetime Achievement Award (1997) and has received numerous other writing awards. In October 2019 he was the recipient of the UCLA Medal, the university’s highest honor.

"I dislike religion very much, Christianity in particular (especially Catholicism, which is what I was born into), and find it mean and dangerous — and hypocritical about sex."

— Rechy, Los Angeles Review of Books (Jan. 17, 2015)

Jack Nichols

On this date in 1938, pioneering gay-rights activist John Richard “Jack” Nichols Jr. was born in Washington, D.C. He was raised in Chevy Chase, Md., and came out as gay to his parents as a teen. He lived with the uncle and aunt of Iran’s Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi for three years and learned Persian. He dropped out of school at age 12.

In 1961 he co-founded the Mattachine Society of Washington, a new branch of the gay civil rights organization originally started in 1950. In 1965 he formed a branch in Florida. He led the first gay rights march on the White House in 1965 and participated in the first of the “Annual Reminder” pickets, which took place at Independence Hall in Pennsylvania on July 4th each year from 1965-69.

In 1967 Nichols became one of the first Americans to talk openly about his homosexuality on national television when he appeared in the documentary “CBS Reports: The Homosexuals.” He disguised his identity because his father, an FBI agent, had allegedly threatened him with death if the government found out Jack was his son and he lost his security clearance. In 1968 he and his partner, Lige Clark, began writing a column called “The Homosexual Citizen,” which appeared in Screw magazine.

Nichols and Clark moved to New York City in 1969 and founded the weekly paper GAY, the first such publication. In 1975 Clark was shot under mysterious circumstances while on a road trip through Mexico, leaving Nichols bereft. His murderers were never apprehended. Nichols continued to write and engage in activism, serving as news editor of the San Francisco Sentinel and senior editor of Gay Today, an online news magazine. Nichols died of complications from cancer of the salivary gland. (D. 2005)

"I’m an agnostic. A non-believer, a heretic, an infidel. Well, you say, an agnostic stands somewhere between belief in God and non-belief. I stand closer to non-belief. When I think about my own religious nature, about spiritual matters, I never include the Sky God in my picture. I’m a humanist, which is like being a spiritualized atheist."

— Nichols' speech at a cancer survivor's meeting in Cocoa Beach, Fla., 1993; reprinted on GayToday.com.

Don Carpenter

On this date in 1931, writer Don Carpenter was born in Berkeley, Calif. He completed high school in Portland, Ore., where his family moved in 1947. After graduating he enlisted in the Air Force and served during the Korean War, stationed in Kyoto, Japan, where he reported for the military newspaper Stars and Stripes. Upon returning home, Carpenter attended Portland State University, where he met Martha Marie Ryherd. They married in 1956 and moved to San Francisco. Carpenter received an M.A. in creative writing from San Francisco State University and taught English before becoming a novelist.

Carpenter’s writing is often perceived as cynical and ominous. He is best known for his novel Hard Rain Falling (1966), which follows the adventures of an orphan from Portland caught in a life of crime and punishment. The novel attempts to answer the question of our existence in a provocative way while additionally addressing issues of systematic conformity in America. Carpenter’s other works include Blade of Light (1968), Getting Off (1971) and From a Distant Place (1989).

He also spent some years in and out of Hollywood during which he wrote the cult film “Payday” (1973) about a rags-to-riches country singer ultimately driven to ruin. He later settled in Mill Valley, Calif., and became a full-time writer. Carpenter struggled with health issues, including tuberculosis and diabetes. He took his own life during the summer of 1995. His novel Friday at Enrico’s (2014), was published posthumously. It is a partially autobiographical take on the lunches he had in the 1970s with other notable authors. (D. 1995)

"I'm an atheist. I don't see any moral superstructure to the universe at all. I consider my work optimistic in that the people, during the period I'm writing about them, are experiencing intense emotion. It is my belief that this is all there is to it. There is nothing beyond this."

— Carpenter, quoted in a 1975 interview cited in The Rumpus online magazine (Nov. 2, 2009)

Leo Rosten

On this date in 1908, journalist and political scientist Leo Rosten was born in Łódź, now a part of Poland. He was born into a Yiddish-speaking family and emigrated to the U.S. at age 3, where his trade unionist parents opened a knitting shop in the Chicago area. He grew up in a working-class neighborhood in which the primarily Jewish residents spoke Yiddish and English. From an early age, Rosten had an interest in books and language that led him to write his first story at the age of 9. He put himself through college and received degrees from the University of Chicago and the London School of Economics.

Emerging into the workforce during the Great Depression, Rosten was unable to find a job that fit his degree. Instead he began teaching English to immigrants at night school. This experience led to his most popular work, The Education of H*Y*M*A*N*K*A*P*L*A*N (1937), published under the pseudonym Leonard Q. Ross. In 1949 he joined the staff at Look magazine in New York, where he remained until 1971.

Rosten also lectured at Columbia University, Yale and the New School of Social Research in New York City. He wrote scripts for films such as “The Conspirators” (1944), “The Dark Corner” (1946) and “Double Dynamite” (1951). Rosten is recognized for his humorous encyclopedic collections The Joys of Yiddish (1968) and The Joys of Yinglish (1989). He also edited A Guide to the Religions of America (1955), Religions in America (1963) and A Guide to the Religions of America: Ferment and Faith in an Age of Crisis (1975).

He married Priscilla Ann Mead, a sister of anthropologist Margaret Mead, in 1935. They had two daughters and a son before divorcing in 1959. She took her own life at age 48 later that year. Rosten married Gertrude Zimmerman in 1960. He died at age 88 in New York City. (D. 1997)

"The purpose of life is not to be happy — but to matter, to be productive, to be useful, to have it make some difference that you lived at all."

— Rosten, "The Myths by Which We Live," The Rotarian, Evanston, Ill. (September 1965)

Nella Larsen

On this date in 1891, Nellallitea “Nella” Larsen (née Walker), who became a well-known Harlem Renaissance writer, was born in Chicago to Mary Hanson from Denmark and Peter Walker from the Danish West Indies. Two years later, Walker disappeared from their lives. Nella took her stepfather’s surname after her mother remarried.

She grew up in Chicago, studied in 1907-08 at Fisk University in Nashville, Tenn., audited classes in Denmark and moved to New York City, where she trained as a nurse. She worked for a year as superintendent of nurses at Tuskegee Institute, then returned to New York in 1916 and married Elmer Samuel Imes, a physicist. By 1920 she had given up nursing and was starting to write. She became a library assistant at a branch of the New York Public Library, now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Her first book, a 1928 novel titled Quicksand, has a young protagonist with resemblances to Larsen, who pointedly disdains the religion she encounters at a fictional Black school. But after seeking refuge and a sense of community in a randomly attended church one night, she is swept up in the emotion of the service and is escorted home afterward by the charismatic preacher, whom she impulsively decides to marry. She moves with him to Alabama, where she is miserable and asks herself, “How could she, how could anyone, have been so deluded.”

Her 1929 novel Passing is about two light-skinned women who take divergent paths. A film adaptation debuted to great acclaim at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival. The film, directed by actress Rebecca Hall, stars Tessa Thompson and Ruth Negga in the title roles.

In 1933, Larsen became the first Black woman to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship, yet never published again. She divorced her husband in 1933 and from 1941 to her death of a heart attack at age 72 worked as a nurse and nursing administrator in a Brooklyn hospital. (D. 1964)

“With the obscuring curtain of religion rent, she was able to look about her and see with shocked eyes this thing she had done to herself. She couldn't, she thought ironically, even blame God for it, now that she knew he didn't exist.”

— Larsen, writing in "Quicksand" about her character Helga Crane (1928)

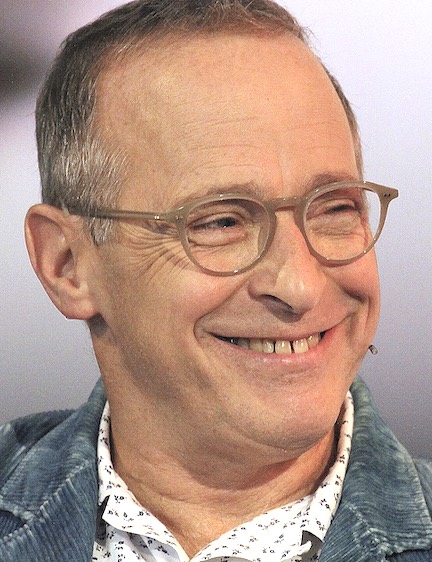

Patrick Somerville

On this date in 1979, American novelist, short story writer and television writer/producer Patrick Somerville was born in the state of Wisconsin, where he grew up in Green Bay and later attended the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He also attended Cornell University and received his MFA in 2005. He has written a range of books from novels such as “The Cradle” (2009) and “The Bright River” (2012) to collections of stories like “Trouble” (2006) and “The Universe in Miniature in Miniature” (2010).

The stories in “The Universe in Miniature in Miniature” discuss the tale of a Chicago man in possession of a supernatural helmet that allows him to experience the inner worlds of those around him. One art student, for example, comes to terms with her own beliefs in a godless world as she struggles through the subjects of ennui, ethics and empathy.

Somerville is known for his talent for writing the voices for a range of characters. He has taught creative writing and English at a number of places, including Cornell, Northwestern University, Auburn State Correctional Facility and the Graham School in Chicago. He has also written episodes for television shows, including “The Bridge” (2013), “The Leftovers” (2015) and “Maniac” (2018).

Somerville at the 2011 Brooklyn Book Festival; editrrix photo under CC 2.0.

"And I think because I grew up without any religion I am particularly obsessed with good and evil. Not somehow 'figuring it out,' but at least knowing it when I see it. I hate the idea of living my whole life and then dying and not having done a good job recognizing and celebrating what's good."

— Somerville, The Sunday Rumpus Interview (June 10, 2012)

Vladimir Nabokov

On this date in 1899, novelist and poet Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, to Yelena Ivanovna (née Rukavishnikova) and Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov, both wealthy and socially prominent. He had four younger siblings, one of whom died in a Nazi concentration camp in 1945 for denouncing Hitler.

The family was nominally Russian Orthodox but lacked religious fervor and Nabokov stopped attending church. Of his mother he would later write: “Her intense and pure religiousness took the form of her having equal faith in the existence of another world and in the impossibility of comprehending it in terms of earthly life.” (“Speak, Memory: A Memoir,” 1951)

English, French and Russian were spoken in the household and Nabokov first learned to read and write in English, disappointing his patriotic father. He published a book of poems in Russian at age 17. During the political ferment of the revolution, the family fled to Crimea and then to England, where Nabokov earned a degree at Trinity College-Cambridge in 1922.

He then joined his family in Berlin, where his father, a political liberal who had started an émigré newspaper in 1920, would die two years later in an assassination attempt by Russian monarchists on government-in-exile leader Pavel Milyukov. Nabokov would draw on his father’s death repeatedly in his fiction.

He stayed in Berlin for 15 years, supplementing his meager writing income by teaching languages, tennis and boxing. He married Véra Evseyevna Slonim, a Russian-Jewish woman, in 1925. Their only child, Dmitri, was born in 1934. He wrote nine novels in Russian, and his final work of Russian fiction, the novella “The Enchanter,” was written in Paris in 1939.

They fled to the U.S. in 1940 and Nabokov joined the faculty of Wellesley College as a lecturer in comparative literature. The position included free time to write creatively and pursue his academic interest in lepidoptery (moths and butterflies). He founded Wellesley’s Russian department and became a naturalized U.S. citizen. He left Massachusetts in 1948 to teach Russian and European literature at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., where he taught until 1959. Among his Cornell students was future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

He published steadily and was a substantial force in the literary world until 1955, when his controversial best-selling novel “Lolita” moved him from newspapers’ books pages to front pages. Ranked fourth on the Modern Library’s list of 100 Best Novels in 2007, it detailed the purported memoir of middle-aged literature professor Humbert Humbert (a pseudonym), who is sexually obsessed with “nymphets,” in particular the 12-year-old Dolores Haze. He marries Dolores’ mother Charlotte and seduces her after Charlotte dies in an accident and Dolores tells him she had sex with an older boy at camp the previous summer.

“And what is most singular is that she, this Lolita, my Lolita, has individualized the writer’s ancient lust, so that above and over everything there is — Lolita,” Humbert writes. In a 1974 analysis, Donald E. Morton wrote: “What makes ‘Lolita’ something more … is the truly shocking fact that Humbert Humbert is a genius who, through the power of his artistry, actually persuades the reader that his memoir is a love story.”

Frederic Babcock, Chicago Tribune books editor, wrote in 1958: “Lolita is pornography, and we do not plan to review it.” Writer Joyce Carol Oates judged it as “one of our finest American novels, a triumph of style and vision, an unforgettable work, Nabokov’s best (though not most characteristic) work, a wedding of Swiftian satirical vigor with the kind of minute, loving patience that belongs to a man infatuated with the visual mysteries of the world.” (Oates in the Saturday Review of the Arts, January 1973)

“Lolita” made Nabokov wealthy and spawned several adaptations on stage and screen, including operas and ballets. Stanley Kubrick directed the first film version (1962), starring James Mason as Humbert and Sue Lyon, 14 at the time, as Lolita.

Nabokov and Véra had moved in 1961 to the Montreux Palace Hotel in Switzerland, where he continued to write and collect butterflies and lived till the end of his life at age 78 in 1977. His last novel was “Look at the Harlequins!” in 1974.

“I don’t belong to any club or group,” he wrote in “Strong Opinions” (1973). “I don’t fish, cook, dance, endorse books, sign books, co-sign declarations, eat oysters, get drunk, go to church, go to analysts, or take part in demonstrations.” According to Donald Morton, “Nabokov is a self-affirmed agnostic in matters religious, political, and philosophical.” (D. 1977)

PHOTO: Nabokov in Berlin in the 1920s.

“In the 1920s I was clawed at by a certain Mochulski [Konstantin, a literary critic and philosopher] who could never stomach my utter indifference to organized mysticism, to religion, to the church — any church.”

— Nabokov responding to whether he believed in God. (Playboy magazine interview, January 1964)

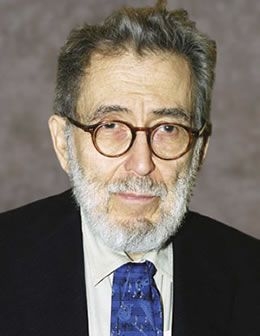

Robert Gottlieb

On this date in 1931, Robert Adams Gottlieb, writer and editor at Simon & Schuster, Alfred A. Knopf and The New Yorker, was born in New York City to Charles and Martha Gottlieb. Growing up, he “was your basic, garden-variety, ambitious, upwardly mobile, hard-working Jewish boy from Brooklyn,” Gottlieb later wrote. His parents were “confirmed atheists” and religion played no part in his upbringing.

He enrolled at Columbia University as an English major, read voraciously (favorites: Henry James and Proust) and co-edited the school’s literary magazine. He graduated in 1952, the year he married Muriel Higgins when she was pregnant with their son and then studied abroad at Cambridge University before joining Simon & Schuster as an editorial assistant in 1955. Two years later he started editing the unknown Joseph Heller‘s manuscript that became the blockbuster titled Catch-22. (He thinks Heller’s Something Happened [1974] is his finest novel, “indeed, one of the finest novels of his time.”)

Gottlieb’s talent and nose-to-the-grindstone work ethic landed him the top editor position at S&S, where he stayed until moving to Alfred A. Knopf in 1968 as editor-in-chief. In 1969, four years after his divorce, he married Maria Tucci, an actress whose father, novelist Niccolò Tucci, was one of his writers. They had two children. In 1987 he succeeded William Shawn as editor of The New Yorker, where Gottlieb was succeeded in 1992 by Tina Brown. He then returned to Knopf as editor-ex officio.

Gottlieb also edited novels by John Cheever, Doris Lessing, Chaim Potok, Charles Portis, Salman Rushdie, John Gardner, Len Deighton, John le Carré, Ray Bradbury, Elia Kazan, Michael Crichton and Toni Morrison. He edited nonfiction books by Bill Clinton, Janet Malcolm, Katharine Graham, Nora Ephron, Katharine Hepburn, Barbara Tuchman, Jessica Mitford, Robert Caro, Antonia Fraser, Lauren Bacall, Liv Ullman, singer Paul Simon, Bob Dylan, Bruno Bettelheim and many others.

He served as the dance critic for The New York Observer starting in 1999 and was the author of biographies of George Balanchine, Sarah Bernhardt and the family of Charles Dickens (who had 10 children). For many years he was associated with the New York City Ballet and published books by Mikhail Baryshnikov and Margot Fonteyn. His autobiography Avid Reader: A Life was published in 2016. He died at age 92 in a New York City hospital. (D. 2023)

“I’ve simply always lacked even the slightest religious impulse — when people talk about their faith, I can’t connect with what they’re talking about. This isn’t a decision I came to, or a deep belief or principle; I’m just religion-deaf, the way tone-deaf people hear sounds but not music. I suppose my religion is reading.”

— Robert Gottlieb, "Avid Reader: A Life" (2016)

Annie Dillard (Quote)

“If God’s escape clause is that he gives only spiritual things, then we might hope that the poor and suffering are rich in spiritual gifts, as some certainly are, but as some of the comfortable are too. In a soup kitchen, I see suffering. Deus otiosus: do-nothing God who, if he has power, abuses it.”

— Writer Annie Dillard was born on this date in 1945 in Pittsburgh. Her personal website lists her religion as "None," although she embraced Catholicism in the late 1980s and part of the 1990s. The quote is from her 1999 memoir "For the Time Being."

Margaret Cole

On this date in 1893, English socialist, politician and poet Margaret Isabel Cole (née Postgate) was born in Cambridge, England, to John and Edith (Allen) Postgate. They raised her with a well-rounded education at Roedean School and Girton College, Cambridge. During her time at Girton, Cole was inspired by the works of intellectuals such as J.A. Hobson, H.G. Wells, Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, George Bernard Shaw and Noel Brailsford.

These readings led her toward a life of socialism, feminism and atheism and away from her conventional Anglican upbringing. Cole became a classics teacher at St. Paul Girls School at Cambridge. Her brother shared some of her interests and was imprisoned during World War I as a conscientious objector.

While working with the No-Conscription Fellowship, she met George Cole, who led a movement known as Guild Socialism. They married in 1918 and joined the socialist Fabian Society before moving to Oxford in 1924. During their time there they taught, co-authored numerous mystery novels and created the Socialist League. Although she was anti-World War I, she espoused military action in the 1930s after witnessing the rise of Hitler and the Nazi Party.

In 1949, her autobiography, Growing Up Into Revolution, was published. She wrote many other books, including a biography of her husband.

Cole was committed to the well-being of London’s citizens and came to be a founding member of the Inner London Education Authority in 1965, where she remained until 1967, when she retired. She received the Order of the British Empire in 1965, the equivalent of being knighted for men, and thus became Dame Margaret Cole. She used her academic exposure to introduce comprehensive education in London throughout the rest of her life. (D. 1980)

PHOTO: Reproduction of a Cole portrait by Australian artist and feminist Stella Bowen, c. 1944.

"[Conscientious objection] on religious grounds was for most part treated with respect, particularly if the sect had a respectable parentage. … But non-Christians who objected on the grounds that they were internationalists or Socialists were obvious traitors in addition to all their other vices, and could expect little mercy.”

— Margaret Cole, "Growing Up Into Revolution" (1949)

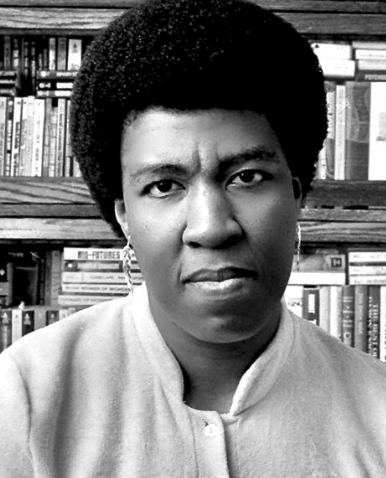

Nikki Giovanni

On this date in 1943, poet Yolande Cornelia “Nikki” Giovanni Jr. was born in Knoxville, Tenn., to Yolande Cornelia Sr. and Jones “Gus” Giovanni. She was nicknamed “Nikki” by her older sister. She grew up in Cincinnati and Wyoming before moving in with her grandparents in Knoxville when she was 15.

Giovanni enrolled at Fisk University in Nashville, her grandfather’s alma mater, where she graduated with honors in history in 1967. She briefly attended Columbia University before starting to teach at Rutgers University’s Livingston College, where she was an active member of the Black Arts Movement. In 1969 she gave birth to Thomas Watson Giovanni, her only child. She also taught at Ohio State and Queens College in New York.

In 1970 she began making regular appearances on a TV program called “Soul!” that combined entertainment and talk promoting Black culture. She also helped design and produce episodes. She has published multiple poetry anthologies and nine children’s books and released seven spoken word albums from 1973 to 2021. In 1987 she started a long career teaching writing and literature at Virginia Tech.

After self-publishing her first book of poetry, Black Feeling Black Talk (1968), she published prolifically, with over 30 works of fiction, nonfiction and poetry collections. Gemini: An Extended Autobiographical Statement on My First Twenty-five Years of Being a Black Poet (1971) was nominated for the National Book Award.

Giovanni was treated for lung cancer in the early 1990s and underwent several surgeries. Called one of 25 “Living Legends” by Oprah Winfrey, she has received numerous awards, including the NAACP Image Award (2000). In her autobiography, she writes, “God is dead. Jesus is dead. Allah is dead.” (Cited by Christopher Cameron in Black Freethinkers: A History of African American Secularism, 2019)

Although she had professed belief in God in a 1969 interview, when interviewed by James Baldwin in 1971, Giovanni stated, “I never wanted to be the most moral person in the world. I would like — I would sell my soul — You know what I mean? What does it profit a man to gain the world and lose his soul? The world! You know what I mean? The world. That’s what it profits him.” (Cited jn Black Freethinkers, ibid.)

PHOTO: Giovanni in 2007 at the Arkansas Literacy Festival in Little Rock; David Quinn photo under CC 2.0.

“I can't dig theology …”

— Giovanni in "A Dialogue" (with James Baldwin), adding that she appreciated churches' music and energy (1973)

Nat Hentoff

On this date in 1925, First Amendment devotee Nat Hentoff was born in Boston to Jewish immigrants from Russia. As a freedom fighter who referred to himself as a “Jewish atheist,” he was characterized by a love for rabble-rousing. His New York Times obituary told the story of how Hentoff, as a 12-year-old, sat on his outside porch on a street leading to the synagogue and ate a salami sandwich on Yom Kippur, the Jewish day of atonement and fasting.

In his 1986 memoir Boston Boy, Hentoff said that he had done so to experience what it was like to be an outcast. He wrote that despite infuriating his father and getting sick, he enjoyed it. (“Nat Hentoff, a Writer, a Jazz Critic and Above All a Provocateur, Dies at 91.” The New York Times, Jan. 7, 2017.)

Hentoff attended Boston Latin, a public school, where he read rapaciously and developed an impassioned ear for jazz musicians. While attending Northeastern University, Hentoff became the editor of a student paper. As a journalist he developed an ardent commitment to uphold the First Amendment. After graduating in 1946 and working for several years at a Boston radio station, Hentoff moved to New York in 1953 and covered jazz music for Down Beat until 1957.

In 1958 he started his longtime job as a writer and columnist for The Village Voice, a counterculture weekly, where he remained as a columnist for 50 years. Hentoff also had a flourishing freelance career, contributing to Esquire, Harper’s, Commonweal, The Reporter and the New York Herald Tribune. He wrote for the New Yorker from 1960 to 1986 and for the Washington Post from 1984 to 2000. Hentoff also lectured at schools and colleges and was part of the faculty at New York University and The New School.

Hentoff wrote over 35 books, including The Collected Essays of A. J. Muste (1966), Black Anti-Semitism and Jewish Racism (1970), Blues for Charles Darwin (1982) and Speaking Freely (1997). His writing expressed his left-wing views on issues focal to civil liberties such as censorship, which he ardently opposed, and education reform. He also produced profiles on political and religious leaders, educators and judges. He held some extremely controversial viewpoints, one of which being his stance against abortion.

Hentoff received several awards, including the National Press Foundation’s award for lifetime achievement for contributions to journalism in 1995. In 2004 he became the first nonmusician to receive the honor of being named one of six Jazz Masters by the National Endowment for the Arts. D. 2017.

"This despicable twelve-year-old atheist is waiting to be stoned. Hoping to be stoned. But not hit. I am, you see, protesting a stoning, or so I will say later that day when my father has discovered how his only son has spent the morning of the holiest day of the year disgracing himself and his father."

— Hentoff memoir on eating a salami sandwich on Yom Kippur; "Boston Boy: Growing Up With Jazz and Other Rebellious Passions" (1986)

Ignacio Ramírez

On this date in 1818, poet, lawyer and journalist Juan Ignacio Paulino Ramírez Calzada was born in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. Known by the pen name “El Nigromante” (The Necromancer), Ramírez co-founded Don Simplicio, a satirical periodical, with politician and journalist Guillermo Prieto. Ramírez, an advocate for educational and economic reforms as well as women’s rights, said that “education is the only possible way to achieve well-being.” (“Ignacio Ramírez,” Jardón.)

He was exiled to California during the reign of Emperor Maximillian. Upon his return to Mexico he was appointed to the Supreme Court. During his time as minister of justice and education, he expanded public education and established secondary education, especially for women and indigenous people.

A lifelong champion of atheism and freethinking, Ramírez caused a scandal when, in a speech to the literary Academy of San Juan de Letrán, he declared God didn’t exist (see quote). Despite the controversy, he was accepted into the academy. Even after his death, his atheism was controversial.

In 1948, artist Diego Rivera painted a mural wherein Ramírez is depicted holding a sign saying “Dios no existe” (God does not exist). Rivera would not remove the inscription so the mural was not shown for nine years until after Rivera agreed to remove the offending words. (D. 1879)

"No hay Dios; los seres de la naturaleza se sostienen por sí mismos." ("There is no God. Natural beings sustain themselves.")

— Ramírez's entry by María Elena Victoria Jardón in "The Encyclopedia of Mexico" (1997)

Octavia Butler

On this date in 1947, science fiction writer Octavia Estelle “Junie” Butler was born in Pasadena, Calif., the only child of Octavia Guy, a housemaid, and Laurice Butler, who shined shoes for a living. Her father died when she was 7 and she was raised by her mother and maternal grandmother.

She graduated from Pasadena City College (1968), then attended California State University and the University of California-Los Angeles. She was encouraged by Harlan Ellison to write. The back of a notebook kept by the young Octavia features a page of confident resolutions, vowing “I shall be a bestselling writer. … My books will be read by millions of people! I will buy a beautiful home in an excellent neighborhood. I will help poor black youngsters broaden their horizons.” (octaviabutler.com)

She struggled, rising daily at 2 a.m. to write before various jobs as dishwasher, telemarketer, even potato chip inspector. But she made good on her vow. Her debut novel Patternmaster (1976) was the first in a five-part series about a group of telepaths ruled by an immortal African. Amazon Studios and JuVee Productions in 2021 started developing a series based on the books, beginning with Wild Seed.

She started writing science fiction after realizing the paucity of Black characters in the genre. Her dystopian writings include themes on Black injustice, climate change and women’s rights. She told the Los Angeles Times in 1998, “I’m black, I’m solitary, I’ve always been an outsider.” (New York Times obituary, March 1, 2006)

In Kindred (1979), a woman travels back in time to an antebellum plantation to save a white, slaveholding ancestor and thus, her own life. Her other books include Parable of the Sower (1993), Parable of the Talents (1998) and Dawn (1987), which was developed for TV by director Ava DuVernay. Dawn is part of Butler’s Xenognesis trilogy. She was working at the time of her death on another sequel, The Parable of the Trickster. The Parable novels, centering on the founding of a new religion called Earthseed, predicted the rise of the Religious Right.

Butler drew on New Testament stories for the Parable books but fell away from religious belief in her teen years, said Natalie Russell, assistant curator at the Huntington Library in Pasadena, where Butler’s materials are archived. “Butler talks about in interviews and other places that she had a very strict Baptist upbringing and that it informed her whole life,” Russell said. “It certainly informed her work and not just in a sense of morality. Its ideas and tropes and were something she drew on for her characters and plots.” (Religion Unplugged online magazine, Nov. 13, 2020)

Butler received two Hugo Awards. She became in 1995 the first science fiction writer to be awarded a MacArthur Foundation fellowship. She received a PEN Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2000 and reached the New York Times best-seller list 14 years after her death.

Her heroines include a 15-year-old in the short story “The Evening and the Morning and the Night,” who rejects belief in a god after her parents die of an incurable disease she has inherited. Butler never married, calling herself “comfortably asocial” and a hermit. With a large frame and standing 6 feet tall, she had health problems, including high blood pressure, and died at age 58 after a fall, perhaps from a stroke, outside her home in Lake Forest Park, Washington. (D. 2006)

“At the moment, there are no true aliens in our lives. No Martians or Tau Cetians, to swoop down in advanced space ships, their attentions firmly fixed on the all-important to us, no god or devils, no spirits, angels, or gnomes. Some of us know this. Deep within ourselves we know it. We're on our own, the focus of no interest except our consuming interest in ourselves.”

— from Butler's 1995 essay "The Monophobic Response" (included in "Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora" ed. Sheree R. Thomas (2000)

Mark Fisher

On this date in 1968, writer, theorist and critic Mark Fisher was born in the United Kingdom. Sometimes referred to by his online pseudonym “k-punk,” Fisher was initially known for his blog where he wrote about politics, music and culture. Fisher earned his B.A. in English and philosophy from Hull University in 1989 before completing his Ph.D. at the University of Warwick in 1999. His Ph.D. thesis, “Flatline Constructs: Gothic Materialism and Cybernetic Theory-Fiction” (1999), explored cybernetics and literature.

A co-founder of Zero Books and Repeater Books, Fisher worked as a philosophy and cultural theory lecturer before publishing his most well-known book, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (2009). For Fisher, “capitalist realism” is the sense that it is easier for the individual to imagine the end of the world than it would be for him/her to imagine the end of capitalism.

Fisher’s work expands on the work of other philosophers and theorists, including Jacques Derrida, Louis Althusser, Fredric Jameson and others. His book Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology, and Lost Futures (2014) popularized Derrida’s concept of “hauntology” — colloquially described as a “pining for a future that never arrived” — by exploring various potential but unachieved futures through cultural sources such as music and film.

Fisher’s The Weird and the Eerie (2017) was published posthumously after his suicide. k-punk: The Collected and Unpublished Writings of Mark Fisher (2004-2016) was published in 2018. (D. 2017)

"The persistence of the fantasy that justice is guaranteed — a religious fantasy — wouldn't have surprised the great thinkers of modernity. Theorists such as Spinoza, Kant, Nietzsche and Marx argued that atheism was extremely difficult to practice. It's all very well professing a lack of belief in God, but it's much harder to give up the habits of thought which assume providence, divine justice and a secure distinction between good and evil."

— Fisher, New Humanist magazine (Winter 2013)

Marci Hamilton

On this date in 1957, Marci Ann Hamilton — litigator, legal scholar, child protection advocate and opponent of “extreme religious liberty” — was born in Dallas, Texas, to Carol and Bill Hamilton, a stay-at-home mom and a sales representative for a national firm.

After earning a B.A. in philosophy and English from Vanderbilt University in 1979, she earned master’s degrees from Penn State University in those subjects in 1982 and 1984, the year she married Peter Kuzma, a Ph.D. organic chemist. Hamilton’s interest in the crossover between philosophy, theology and existentialism attracted her to the work of philosophers like Kierkegaard and Nietzsche.

She then earned a J.D. in 1988 from the University of Pennsylvania Law School, where she was editor-in-chief of the Law Review. She clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor (one of her idols) and Judge Edward Becker of the 3rd Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals.

Hamilton is the Fels Institute of Government Professor of Practice and a Resident Senior Fellow in the Program for Research on Religion at the University of Pennsylvania. Previously she held the Paul R. Verkuil Chair in Public Law at the Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University in New York City. In 2016 she founded CHILD USA, a nonprofit academic think tank dedicated to improving laws and public policy to end child abuse and neglect.

She successfully challenged the constitutionality of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) at the Supreme Court in Boerne v. Flores (1997). She has represented numerous cities, neighborhoods and individuals dealing with state-church issues as well as claims under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act. Regarding Boerne (pronounced BUR-nee), Hamilton said, “I was essentially the only law professor in the country who was very publicly saying that extreme religious liberty was wrong. Most of the law professors were on the other side. (Omnia Magazine, University of Pennsylvania, May 21, 2020)

In the preface to God vs. the Gavel: The Perils of Extreme Religious Liberty (2014), a revision of Hamilton’s God vs. the Gavel: Religion and the Rule of Law (2005), she notes how after her Boerne victory (which Congress and states later got around by passing new RFRAs), she “was led on a journey into the underside of religion, because all the groups that lobby against religion sought me out. They earnestly and generously educated me about the facts of religiously motivated illegal behavior.”

Hamilton adds in the preface, “Ten years later, I am no longer shocked at the unacceptable behavior of too many believers, but I am even more determined that Americans learn about the dangers inherent in the religious liberty regime that was initiated in 1993 with the RFRA. The Framers called too much liberty ‘licentiousness.’ I simply call it extreme.”

In the Omnia interview, Hamilton said: “Working on all these issues on the opposite side of organized religion had never been part of any plan. My husband’s Catholic and I’m Presbyterian. We’re not atheists by a long shot. But when all the clergy sex abuse reporting started happening, I began getting calls from all over the country.”

She reached out to offer her help to plaintiffs’ attorney Jeff Anderson in 2011 in the wake of a Philadelphia grand jury report about clergy sex abuse. “I have a personal stake in this. My children are Catholic. My daughter was baptized by a pedophile priest. I have family pictures with a pedophile at one of the most important ceremonies of a child’s life. So I am in it, yes, in Philadelphia. Because it’s the only way to make this archdiocese do the right thing.” (Philadelphia Business Journal, March 27, 2013)

Hamilton has “profound contempt” for any institution or person covering up pedophilia or otherwise endangering children, e.g., denying them medical care due to religious beliefs. “I criticize the failure to protect children from sexual abuse wherever I see it, whether it is in a university, a private school or organization, or a public school. The whole culture needs to wake up and do better on this issue. The Catholic Church’s problem is that it is the largest institution in the world, and its victims have been coming out of the woodwork.” (Omnia, ibid.)

CHILD works to eliminate statutes of limitation so that abusers can be prosecuted no matter how long ago the crime occurred. Dozens of states have passed Child Victim Acts to enable that. Hamilton and co-counsel made history in March 2020 when they filed the first two lawsuits against the Church of Scientology for child sex abuse.

She received the 2015 Religious Liberty Award from the American Humanist Association and was the recipient in 2014 of FFRF’s Freethought Heroine Award. Her acceptance speech titled “Extreme Religious Liberty Is Tyranny” can be viewed or read here. Hamilton also wrote FFRF’s amicus brief before the Supreme Court in the Hobby Lobby challenge of the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate.

“The ‘Restoration’ in the title is a lie. It was not restoring anything that had been in place before. It was putting in place what the religious litigants had failed to obtain for years.”

— Hamilton, referring to the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, FFRF convention speech (Los Angeles, Oct. 24, 2014)

Mara Wilson

On this date in 1987, actress and writer Mara Elizabeth Wilson was born in Burbank, Calif., to Suzie (Shapiro) and Michael Wilson and was raised Jewish in her early childhood. She played Natalie Hillard, the daughter of Robin Williams and Sally Field in “Mrs. Doubtfire” when she was 5 and had a role in the remake of “Miracle on 34th Street” in 1994.

She had the title role in 1996 in director Danny DeVito’s “Matilda,” an adaptation of Roald Dahl’s young-adult book. Her mother died of breast cancer during filming of the highly acclaimed movie when Wilson was 9. She received the National Association of Theatre Owners’ Young Star of the Year award in 1995. She retired from acting after her role in “Thomas and the Magic Railroad” (2000). “I like to think of it as a mutual break-up: Hollywood didn’t really want me anymore, and I was over it, too,” she later wrote on her website Mara Wilson Writes Stuff.

She returned to acting in 2012 but not in any serious way, with relatively few appearances. She writes extensively, and her work has appeared on Elle.com, McSweeney’s, The New York Times, Vanity Fair, the Daily Beast, Jezebel and other outlets. Her play “Sheeple” premiered at the New York International Fringe Festival in 2013, and she is the author of the 2016 autobiography Where Am I Now? True Stories of Girlhood and Accidental Fame.

Wilson has been open about her struggles with mental illness since her OCD diagnosis at age 12 and about her lack of religious belief. On the live show and podcast “RISK!” (Dec. 14, 2015), she talked about her Catholic stepmother’s efforts to get her and her younger sister Anna to convert: “[Anna] became Catholic, and I became an atheist.”

“Mara came out publicly as bi — although she now tends to prefer the label queer (‘I like queer more than I like bisexual, but I have no problem with people calling me bisexual,’ she says) — on Twitter in the wake of June 2016’s tragedy at the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando.” (“Matilda Is Bi and So Am I,” Sept. 20, 2017) She was the American Humanist Association’s 2019 LGBTQ Humanist Award recipient.

Wilson read the His Dark Materials trilogy by Philip Pullman when she was 15: “It’s a retelling of ‘Paradise Lost’ with the premise that the God that we know is not actually God. I was OCD and I worried a lot about what God thought. These books put forward a pretty good case that maybe there was no God. I remember breaking down and crying when I read it because it altered the way I saw the world.” (TheaterMania interview, Aug. 7, 2013)

In 2018 she was offered a script about a Christian redemption movie that suggested famous child actors for roles in the movie. On Twitter she said she rejected the movie’s premise, which implied that child actors somehow need to be redeemed. “It’s as if they want us to be part of a very specific redemption narrative. Being a child star, falling from grace and public view, then finding Jesus and making liberal Hollywood safe for right-wing Christians.” (@MaraWilson tweet, May 25, 2018)

She wrote in a follow-up tweet: “The idea that our lives might be more than a cautionary tale, or some cheap inspiration, is beyond their comprehension.” In a 2017 NPR interview, “The Simpsons” voice actor Nancy Cartwright said the young Wilson inspired a character’s voice in the episode “Bart Sells His Soul.”

PHOTO: Wilson in Los Angeles at the premiere of the movie “Knives Out” in 2019; photo via Shutterstock by Featureflash Photo Agency

“Eventually, I saw Julia Sweeney‘s monologue ‘Letting Go of God.’ That changed everything. I walked out of the theater and said, ‘You know what, I don’t believe there is a God, and I’m OK with that.’ "

— Wilson, TheaterMania interview (Aug. 7, 2013)

Jean de la Bruyère (Quote)

"To what excesses will men not go for the sake of a religion in which they believe so little and which they practise so imperfectly!"

— Jean de la Bruyère, French author (1645-1696) known for his satirical writing, "Caractères" (Characters), published in 1688

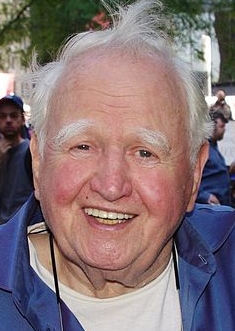

Malachy McCourt

On this date in 1931, actor-writer Malachy Gerard McCourt was born in Brooklyn, N.Y., one of seven children born to Irish immigrants Malachy and Angela (Sheehan) McCourt. The family moved back to Ireland during the Great Depression, with the children growing up in poverty due to their father’s frequent absence and alcoholism — a disease his namesake would later fall prey but not succumb to — and their mother’s subsequent depressed state. At age 20, McCourt returned to New York.

After an Air Force hitch, he worked as a laborer, dishwasher, longshoreman and concrete inspector for the New Jersey Turnpike. He started the first singles bar in Manhattan, then began a tumultuous radio talk show career in 1970, which ended six years later with his firing. He had some success as a stage and TV actor and eventually made several movies. After divorcing his first wife Linda Wachsman after they had two children, he married Diana Galin in 1963. They had two more children together. He took his last drink of alcohol in 1985.

While his brother Frank was the more acclaimed writer (particularly for his Pulitzer Prize-winning Angela’s Ashes), McCourt also wrote extensively, including his own best-selling memoir A Monk Swimming (from his mishearing as a child the Hail Mary’s “Blessed art thou amongst women”).

He also wrote about being molested by two priests, and in Death Need Not Be Fatal took the Catholic Church to task for failing him personally and the poor and impoverished generally. He was the 2006 Green Party candidate for New York governor, losing to the Democratic candidate Eliot Spitzer.

He died at age 92 at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. (D. 2024)

PHOTO: By David Shankbone under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0

"I started out life as a member of the One Holy Roman Catholic Apostolic Church, and I am coming to the end of it without organized religion or mystical thinking. I am an atheist, thank God, with no fear of hell and no hope of heaven."

— "Death Need Not Be Fatal" (Center Street, May 16, 2017)

Truman Capote