statesmen

‘Wall of Separation’ Phrase Coined

On this date in 1802, President Thomas Jefferson coined the famous phrase describing the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment as erecting “a wall of separation between church and state.” He used the phrase in his famous letter to the Baptists of Danbury, Connecticut, who had asked him to explain the meaning of the First Amendment’s phrase “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”

"I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibit the free exercise thereof, thus building a wall of separation between church and state."

— Jefferson's letter to the Baptists of Danbury (Jan. 1, 1802)

Marcus Tullius Cicero (Quote)

"Reason is the mistress and queen of all things."

— Roman statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BCE), born on Jan. 3, 106. "Tusculanae disputationes." Cicero also authored "Of the Nature of the Gods."

Nick Clegg

On this date in 1967, Nicholas William Peter Clegg was born in Chalfont St. Giles in Buckinghamshire, England. He speaks five languages: English, Dutch, French, German and Spanish. Clegg studied anthropology at Cambridge University and received a Master’s degree in political philosophy at the University of Minnesota. He interned at The Nation in New York under Christopher Hitchens before returning to Europe, where he interned at the European Commission and earned an M.A. in European affairs at the College of Europe in Bruges.

Clegg worked as a journalist and at the European Commission before being elected Member of the European Parliament for the East Midlands in 1999. In 2005 he was the liberal parliamentary candidate for Sheffield Hallam and was elected. Clegg was elected leader of the Liberal Democrats and rose to national prominence in the 2010 general election. The third-party Liberal Democrats received 23% of the vote and he became a power broker, as neither of the two major parties won a majority of seats. Clegg chose to ally with the Conservative Party and became deputy prime minister.

After being elected leader in 2007, Clegg was asked on the BBC Radio program 5 Live if he believed in God. He replied that he did not, though he later elaborated that he had “great respect” for people of faith. Clegg has stuck to his guns, continuing to describe himself as agnostic during the 2010 election campaign.

Clegg’s wife, Spanish-born Miriam González Durántez, is Catholic. They married in 2000 and have three sons.

Since 2013 he has hosted the weekly radio show “Call Clegg” and in 2018 debuted a podcast called “Anger Management with Nick Clegg, ” in which he interviews prominent people about the politics of anger. In October 2018 Facebook announced Clegg had been hired as a vice president, public relations officer and lobbyist in the area of global affairs and communications.

PHOTO: By David Angell under CC 2.5.

BBC: Do you believe in God?

CLEGG: No. … I am not an active believer.— Clegg, BBC interview (Dec. 20, 2007)

Albert Gallatin

On this date in 1761, Albert Gallatin (né Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin) was born in Geneva, Switzerland. He studied mathematics, natural history and Latin at Geneva University, where he graduated with honors in 1779. Voltaire had been a friend of his grandmother and was an influence on Gallatin, also a deist. In 1780, to evade family pressure to join up with the Hessians, Gallatin gave up family and fortune to emigrate to America to demonstrate “a love for independence in the freest country of the universe.”

He taught French at Harvard, then moved to Virginia in 1785, where he was elected to the legislature. After being elected to the U.S. Senate, Gallatin was rejected by the body as a non-citizen, but returned to Congress in the House in 1795. He wrote “Views of the Public Debt, Receipts & Expenditures of the U.S.” in 1800, which is described by the U.S. Department of the Treasury website as “still a classic” analysis of the fiscal operations of government under the Constitution.

Jefferson believed the Alien and Sedition Act was framed to drive Gallatin — who worked to keep down expenses, especially for war and the military — from office. Jefferson offered Gallatin the position of secretary of state. He served under both Jefferson and Madison from 1801-13. He was minister to France from 1815-23, then served as an envoy to Great Britain. A lifelong scholar, he was a co-founder of New York University.

Determined to keep it secular, he later resigned from a position there when “a certain portion of the clergy had obtained control.” Gallatin opposed slavery and helped negotiate the Treaty of Ghent, ending the War of 1812. He served with the American Ethnological Society, helping to preserve native languages, and was president of the New York Historical Society. (D. 1849)

"[A] foundation free from the influence of clergy."

— Gallatin's stated aim for New York University, cited by Joseph McCabe, "A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists" (1920)

Victor Hugo

On this date in 1802, author Victor Marie Hugo was born in Besançon, France, the son of a Napoleonic officer. By 17 he had earned three prizes for poetry at Toulouse. King Louis XVIII awarded Hugo a royal pension after his Odes and Poetry appeared (1822). His first drama, “Cromwell,” was published in 1827.

After devoting nearly two decades to stage writing, Hugo turned to fiction. His novel, known in English as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, was published in 1831 and featured a villainous priest. It has been turned into several movies and dramatizations, including a Disney cartoon (which interestingly turned villain Claude Frollo into a layperson). Les Misérables was published in 1862 in 10 languages. The epic tale has spawned several movies and stage productions, including its Broadway debut in 1987.

Hugo was forced to flee to Belgium after Napoleon III’s coup d’etat in 1851. He eventually returned to France when the republic was proclaimed and was elected a senator in 1876. Although his religious views wavered over his long and tempestuous life, Hugo was anti-clerical, freedom-loving and generally considered to have been a rationalistic deist.

He married Adèle Foucher in 1822 and they had five children before her death in 1868. He suffered a mild stroke in 1878 and recovered. He died of pneumonia in Paris at age 83. (D. 1885)

"An intelligent hell would be better than a stupid paradise."

— from Hugo's play "Ninety-three" (1881)

Joel Barlow

On this date in 1754, Joel Barlow was born in Redding, Connecticut. Educated at Dartmouth College and Yale, he served as a chaplain in the Revolutionary War. His edition of The Book of Psalms, issued in 1785, was widely used by the Congregationalists. Barlow, a liberal thinker, left the ministry, took up law and was admitted to the bar in 1786. As a writer and poet he was a member of the well-known “Hartford Wits.”

Barlow became a deist after traveling in France, according to C.B. Todd (Life and Letters of J. Barlow, 1886). Barlow’s claim to freethought fame was as counsel to Algiers, when he secured the release of prisoners and negotiated the Treaty with Tripoli of 1797, which stated that the U.S. was not a Christian nation. It was written in Algiers in Arabic and signed on Nov. 4, 1796. Barlow translated the treaty, which was ratified by the U.S. Senate on May 29, 1797.

George Washington was president when the treaty was signed in Tripoli, but it was signed by John Adams. Barlow also befriended Thomas Paine and was responsible for getting Paine’s The Age of Reason published during his imprisonment in Paris. Barlow became U.S. ambassador to Napoleon’s court in 1811 and died in 1812 at age 58 in Poland while traveling to meet Napoleon during his retreat from Moscow.

“As the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion; as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion, or tranquility, of Mussulmen; and as the said States never entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mahometan nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries."

— Article 11, Treaty of Tripoli

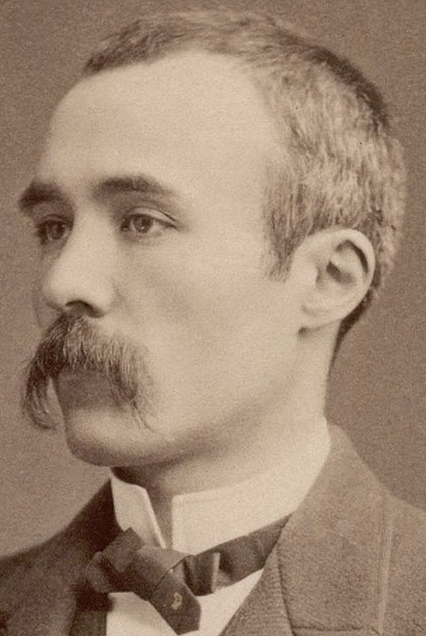

Léon Gambetta

On this date in 1838, Léon Gambetta was born in Cahors, France. In 1857, he went to Paris to study law, and was called to the bar in 1859. He expressed very strong republican opinions (France was at that time governed by Napoleon III in the Second Empire) and in 1868 he became famous for his defense in a political case, called the Affaire Baudin. Baudin had died in an attempted coup, and Gambetta defended eight journalists who were prosecuted for attempting to build a memorial to him.

In 1869 Gambetta was elected to the Legislative Assembly, where he opposed the Franco-Prussian War, which broke out in July 1870. He was instrumental in forming a provisional government and declaring a republic after Napoleon III was captured by the Germans. Gambetta then helped to lead the defense of France from Germany. He briefly left government in March 1871 after ratification of a peace treaty which gave up Alsace and Lorraine. He was then elected to the National Assembly in July of that same year, where he was instrumental in the vote to institute the Third Republic, rather than to restore a Bourbon monarchy.

In addition to being a republican, Gambetta was part of the anti-clerical faction and an avowed atheist. He spoke of the conflict between “those who pretend to know everything through revelation, in an immutable manner, and those who march, thinking and progressing, to the suggestions of science, which every day accomplishes progress and which pushes back the boundaries of human knowledge.” (The End of the Soul: Scientific Modernity, Atheism, And Anthropology in France, 1876–1936 by Jennifer Michael Hecht, 2003)

Gambetta remained active in politics, becoming president of the Chamber of Deputies, until he died at age 44 of appendicitis. He wanted France to be a beacon for freethought as well as political freedom, and on his death made a contribution to freethought — his brain went to the Society of Mutual Autopsy, a group that wished to investigate the workings of the brain through dissection, attempting to show physical traits in connection with mental properties. (D. 1882)

"Clericalism, that’s the enemy!"

— Gambetta, quoted in "The End of the Soul" by Jennifer Michael Hecht (2003)

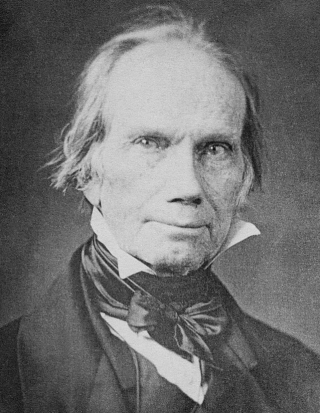

Henry Clay

On this date in 1777, American statesman and orator Henry Clay was born in Hanover County, Virginia. Clay was the seventh of nine children born to John and Elizabeth Hudson Clay. After being admitted to the Virginia bar in 1797, Clay moved to Lexington, Kentucky, where he worked as a frontier lawyer. Clay was known for his enjoyment of drinking and gambling and as a horse aficionado. He married Lucretia Hart, the daughter of a wealthy Lexington businessman, in 1799. In their 50 years of marriage, they had 11 children.

Clay began his political ascendance in 1803, when he was elected to the Kentucky General Assembly. As a “Jeffersonian” politician, he began his career as an avid states’ rights advocate. Clay represented former Vice President Aaron Burr in 1806 after Burr was accused, and later found guilty, of plotting an expedition into Spanish Territory to create a new empire.

That same year, at age 29, Clay was appointed to the U.S. Senate. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1811, where he eventually served as speaker. Clay went on to serve multiple terms in both the House and Senate, later serving as President John Quincy Adams’ secretary of state in the 1820s.

Clay earned a reputation as a war hawk when he became one of the primary instigators for the War of 1812 against Britain. However, he was subsequently dubbed “The Great Pacifier” for his role in making amends with Britain after the war. He was selected as one of the five delegates to negotiate a peace treaty at Ghent, Belgium. Although he failed in his two presidential runs for the Whig Party in 1832 and 1844, Clay remained involved with politics until his final days.

His father was a Baptist preacher but Clay belonged to no church until 1847, when he was baptized as an Episcopalian. Although a theist he was a strong advocate for separation of state and church. D. 1852.

"All religions united with government are more or less inimical to liberty. All, separated from government, are compatible with liberty."

— 1818 speech, "The Life and Speeches of the Hon. Henry Clay, Vol. I," ed. Daniel Mallory (1857)

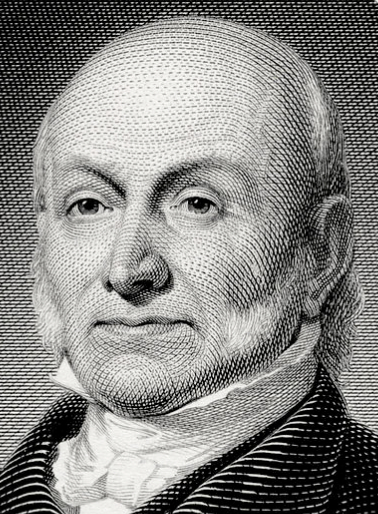

John Quincy Adams

On this date in 1767, John Quincy Adams was born in Massachusetts. He witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill from above his family’s farm and accompanied his father John Adams (U.S. president 1797-1801) on a mission to France at age 12. Adams studied in France and later at the University of Leyden in Holland. He graduated from Harvard at 26 and began a career as lawyer, professor, writer and diplomat.

He was elected to the Massachusetts Senate in 1802 and became a U.S. senator in 1803. He spent several years as minister to Russia under President James Madison. He was one of the negotiators of peace with England in 1814, then served as minister to England until President James Monroe appointed him secretary of state.

Adams authored the Monroe Doctrine and helped negotiate acquisition of important territories. During his candidacy for president, no candidate — Andrew Jackson, Adams, W.H. Crawford or Henry Clay — received a majority of votes. Although Adams was in second place, the House of Representatives with Clay’s support elected Adams president. As president, he proposed a network of highways, the financing of scientific experiments and the building of an observatory.

He was defeated in 1828 but returned to Congress in 1830 and held his seat until his death in 1848. His distinguished career there, earning him the sobriquet of “Old Man Eloquent,” included his advocacy for the right of petition of abolitionist societies. He battled for eight years and finally succeeded in ending a Southern-imposed gag rule automatically tabling petitions against slavery.

Like his father, he was a Unitarian. He was critical of Sabbatarians and preachers who “rave and rant and talk nonsense for an hour” during sermons. (Diary entry, The Religious Beliefs of our Presidents.) Adams collapsed from a stroke on the floor of the U.S. House at age 80 and died two days later. (D. 1848)

"This young fellow, who was possessed of most violent passions, which he with great difficulty can command, and of unbounded ambition, which he conceals perhaps, even to himself, has been seduced into that bigoted, illiberal system of religion, which, by professing vainly to follow purely the dictates of the Testament, in vain contradicts the whole doctrine of the New Testament, and destroys all the boundaries between good and evil, between right and wrong.”

— J.Q. Adams, diary entry, "Life in a New England Town," 1787-88, cited by Franklin Steiner in "The Religious Beliefs of Our Presidents" (1936)

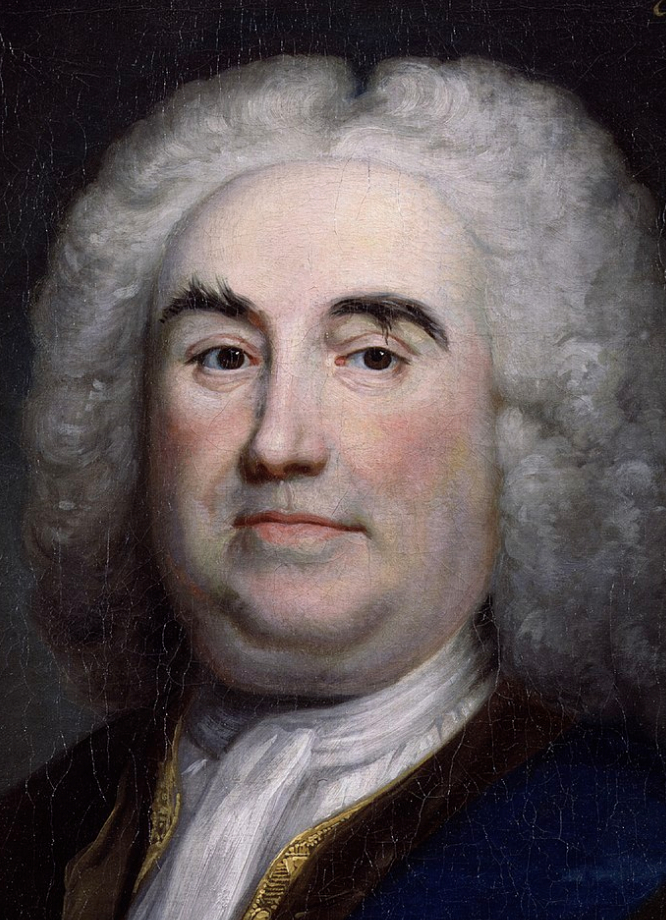

Robert Walpole

On this date in 1676, British statesman Robert Walpole was born in Houghton, Norfolk, one of 19 children. Educated at Eton and Cambridge, he represented King’s Lynn in the House of Commons for most of his adult life. He headed the War Office as secretary in 1708 and was named treasurer of the Royal Navy in 1710. That year he was imprisoned by the Tories for leading the opposition Whigs and was barred from office until 1715. He then became First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Walpole was the only public official to openly oppose the Spanish War and is considered by some as one of England’s greatest statesmen. Walpole has often been called England’s “first prime minister.” He is also its longest serving. Although he publicly identified with the Church of England for political expediency, biographer A.C. Ewald called him a “sceptic as regards religion” who “carefully avoided ever coming into collision with the clergy.”

When Queen Caroline, a deist, lay dying, it was advised that the archbishop of Canterbury be summoned. Walpole, who was in attendance, remarked, “Let this farce be played; the Archbishop will act it very well. … It will do the Queen no hurt, no more than any good.” (Lord Hervey’s “Memoirs”) (D. 1745)

"A man whose life reflected a genial paganism, who regarded all creeds with the impartiality of indifference, and who looked upon religion as a local accident and as the result of hereditary influences, he now saw how powerful was the hold of the Church of England upon his sons.”

— "Sir Robert Walpole: A Political Biography, 1676-1745" by Alexander Charles Ewald (1878)

Georges Clemenceau

On this date in 1841, French statesman and journalist Georges Clemenceau was born in France. Clemenceau followed in his father’s footsteps by becoming a physician and a freethinker. At 16 he was briefly suspended from school for debating Christianity with a teacher. Clemenceau began writing for Emile Zola‘s newspaper Travail, advocating a republic and free speech, and served 63 days in jail in 1862 as a student demonstrator under the reign of Napoleon III.

As a foreign correspondent for Le Temps, he went to New York City in 1865. He met his wife-to-be teaching French at a ladies seminary in Connecticut. Clemenceau’s book The Great God Pan (1869) described how superstitions live on under new guises. He also translated John Stuart Mill’s book Auguste Comte and Positivism. Returning to France, he became mayor of Montmartre, served as a member of the Paris Municipal Council (1871-76) and was elected five times to the National Assembly.

During an interlude when he left politics, Clemenceau returned to journalism. His newspaper articles, permeated with anti-clericalism and the promotion of rationalism, eventually were bound into 19 volumes. He contributed to L’Aurore newspaper and worked tirelessly for the release of Alfred Dreyfuss, writing more than a thousand influential articles about the case.

Known as “The Tiger,” the politician returned to the Assembly in 1902, became interior minister, then prime minister (1906-09). Clemenceau was again elected prime minister in 1917 and was toasted as “Pere Victoire” (Father Victory) at the close of World War I. Clemenceau was a connoisseur of the arts and a personal friend of Rodin. He was buried, per instructions, with no rites. D. 1929.

"Not only have the ‘followers of Christ’ made it their rule to hack to bits all those who do not accept their beliefs, they have also ferociously massacred each other, in the name of their common ‘religion of love,’ under banners proclaiming their faith in Him who had expressly commanded them to love one another."— Clemenceau memoir, "In the Evening of My Thought" (Au Soir de la pensee), 1929

Robert Stout

On this date in 1844, New Zealand statesman Robert Stout was born in the Shetland Isles, Scotland. He was educated in parish schools, qualified as a student teacher at age 13, then as a surveyor in 1860. Stout emigrated to New Zealand in 1863. After teaching in Dunedin, he studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1871. He served as a member of the Provincial Council of Otago in 1872 and was first elected to the House of Representatives in 1875 as a Liberal. He served as attorney general and minister for lands and immigration in 1878-79.

He became president of the Dunedin Freethought Association in 1880 and defended the Auckland Rationalist Association when it was threatened with prosecution for selling its magazine on Sundays. Stout eventually introduced a bill, which passed, reducing Blue Law fines and restrictions. He was often described as New Zealand’s version of Charles Bradlaugh and America’s Robert Ingersoll. He was returned to Parliament in 1884 and served as premier, attorney general and minister of education from 1884-87. He was knighted in 1886.

Stout promoted secular secondary schools and medical and welfare services and was sympathetic to the Maori and land reform. The Married Women’s Property Act became law while he was prime minister. Stout returned to Parliament in time to finally see passage of women’s suffrage in 1893, a reform he had promoted. He was appointed chief justice, serving from 1899-1926. He was also chancellor of New Zealand University (1903-23).

Stout was appointed after retiring as chief justice to the Legislative Council, where he immediately defended secular education, which was under attack by religionists seeking to introduce bible reading and prayers in school: “I fear that Parliament may set up a little state church to make people morally good. … it will make them immoral, for it will inaugurate bitterness and ill feeling.” He married Anna Paterson Logan, the daughter of social reformers and freethinkers, and they had six children. D. 1930.

"We recognise no authority competent to dictate to us. Each must believe what he considers to be true and act up to his belief, granting the same right to everyone else."

— Stout, inaugural address as Dunedin Freethought Association president, 1880

John Wilkes

On this date in 1727, John Wilkes, future lord mayor of London, was born in England. He studied at Leyden University. Wilkes was known for his witticisms, once announcing before a card game, “I am so ignorant that I cannot tell the difference between a king and a knave.” Wilkes became high sheriff of Buckinghamshire in 1754 and was elected a member of Parliament for Aylesbury in 1757, where he agitated for reform.

He founded the periodical North Briton in 1762 to campaign against the king and his prime minister. Wilkes was prosecuted for seditious libel for an article appearing in April 1763 and was sent to the Tower but was released under parliamentary privilege.

His “Essay on Woman” (1763), which was both bawdy and blasphemous, was burned by the hangman. Parliament voted to repeal the privilege of arrest for seditious writings and Wilkes escaped arrest by fleeing to France, where he was welcomed by Baron d’Holbach and Diderot. After Wilkes returned to England, he was arrested. A crowd of 15,000 assembled at the prison where he was held, chanting “Damn the King.” Troops opened fire and killed seven in the Massacre of St. George’s Fields.

Wilkes, sentenced to 22 months, was expelled from the House of Commons but voters reelected him. After a long fight he was seated. A deist, he made a campaign for religious toleration a priority. Wilkes supported America in the War of Independence. He became lord mayor of London in 1774. His popularity waned toward the end of his life as he became more conservative. He died at age 72 in London of a disease known at the time as marasmus. (D. 1797)

Klas Pontus Arnoldson

On this date in 1844, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Klas Pontus Arnoldson was born in Goteburg, Sweden. He left school after his father died at age 16 and worked for the Swedish State Railways for two decades. He was elected to the Riksdag, the Swedish parliament, from 1882-87, where he championed expansion of the franchise, anti-militarism and political neutrality for Sweden. He founded the Swedish Peace and Arbitration Society in 1883 and edited several journals.

He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1908 for his pacifist work, especially during the 1895 dissolution of the union between Norway and Sweden, in which he controversially sided with Norway. After concentrating on largely journalistic writing, Arnoldson wrote several major works during his last three decades, including Religion in the Light of Research (1891). D. 1916.

“Familiar with the humanistic tenets of religious movements originating in the nineteenth century in Great Britain and in the New England section of the United States, he decried fanatic dogmatism and espoused essentially Unitarian views on truth, tolerance, freedom of the individual conscience, freedom of thought, and human perfectability.”

— from Arnoldson's Nobel Prize biography

Robert Dale Owen

On this date in 1801, Robert Dale Owen, oldest son of Robert Owen, was born at New Lanark, Scotland, his reformer father’s settlement. When his father bought a town in Indiana for $30,000 to experiment with a model community, Robert accompanied him to New Harmony, where he edited the New Harmony Gazette, with strong freethought overtones. Although the community failed within three years, it became known as a center for advances in education and scientific research. Residents established the first free library, a civic drama club and a public school system open to men and women.

After his father returned to Great Britain, Owen became a naturalized U.S. citizen. He worked with Frances Wright on many reforms and enterprises, including abolition, women’s rights, pacifism, editing The Free Enquirer and helping found the Working Men’s Party. In 1835 Owen was elected to the Indiana Legislature and in 1843-47 served in the U.S. House of Representatives, where he played a key role in promoting public education, in part by supporting the founding of the Smithsonian Institution.

Owen represented the U.S. as a diplomat in Naples for several years. On Sept. 17, 1862, he wrote President Lincoln to urge him to use his power to end slavery. Five days later, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. To the concern of fellow freethinkers, Owen toyed with the spiritualism movement but was eventually disillusioned by it. His books include several on abolitionism and his autobiography Threading My Way (1874).

He married Mary Jane Robinson before a justice of the peace In New York City in 1832. After an extended trip to Europe, they relocated to New Harmony and had six children. His wife died in 1871 and he married Lottie Walton Kellogg in 1876, a year before he died at age 75 in Lake George, N.Y. (D. 1877)

“For a century and a half, then, after Jesus’ death, we have no means whatever of substantiating even the existence of the Gospels, as now bound up in the New Testament. There is a perfect blank of 140 years; and a most serious one it is.”

— "Discussion on the Existence of God, and the Authenticity of the Bible" by Robert Dale Owen and Origen Bacheler (1833)

William Pitt

On this date in 1708, William Pitt, statesman and the first Earl of Chatham, was born in England. Educated at Eton and Oxford, he entered Parliament at age 27 in 1735. After one of his speeches in 1736 offended the king, Pitt was dismissed from the army. He continued eloquent calls for reform in the House of Commons, served in several prestigious posts and in 1756 was named leader of the House. Pitt, known as “the Great Commoner,” was England’s most powerful politician by 1760 and was known for his honesty. (He’s also referred to as Pitt the Elder to distinguish him from his son, William Pitt the Younger, who also was a prime minister.)

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was named for Pitt, who served as prime minister during the Seven Years’ War against the French in the colonies. He argued in Parliament against the Stamp Act and introduced many measures to placate the Americans, which were all voted down, such as recalling British troops from Boston. Pitt advised, “You cannot conquer the Americans.” The king consequently called him “a trumpet of sedition.”

Pitt was believed by some to be author of an unsigned “Letter on Superstition” published in the London Journal in 1733 and reprinted with his name in 1873. It called for a “religion of reason.” Biographer Basil Williams in his Life of William Pitt (1913) disputed that claim. Yet Williams’ research found that Pitt was a deist with “a simple faith in God,” who wrote a “fierce denunciation” of those with a “superstitious fear of God.”

There is agreement Pitt had no ministration from the church on his deathbed. “Lord C[hatham] died, I fear, without the smallest thought of God,” recalled William Wilberforce, a friend of Pitt’s son (Correspondence of William Wilberforce, 1840). Pitt, who suffered from gout most of his life, collapsed at age 70 during debate on granting independence to the colonies, which he opposed, and died shortly thereafter. (D. 1778)

“[A]theism furnishes no man with arguments to be vicious; but superstition, or what the world means by religion, is the greatest possible encouragement to vice, by setting up something as religion which shall atone and commute for the want of virtue.”

— Pitt, "Address to the People of England," the London Journal (1733)

Pedro Pablo Abarca Aranda

On this date in 1719, Spanish statesman Pedro Pablo Abarca de Bolea y Jiménez de Urrea, later the 10th count of Aranda, was born in northern Aragon. He started ecclesiastical studies in the seminary of Bologna, but at age 18 changed to the Military School of Parma. In 1740 he was severely wounded in combat in the War of the Austrian Succession. He then lived in Paris, where he met Diderot and Voltaire and studied the Encyclopédie and Enlightenment movements.

After an ambassadorship to Poland, Aranda became governor of Valencia in 1764. When Charles III was driven from the capital in a 1766 riot, he summoned Aranda to Madrid and made him president of the Council of Castile. Until 1773 he was the most important government minister in Spain. He restored order and aided the king in his work of administrative reform.

Perhaps his greatest achievement, which endeared him throughout Europe to the philosophical and anti-clerical parties, was his work on behalf of the suppression and expulsion of the Jesuits, whom the king considered responsible for the 1766 riot.

Aranda was well-known to American revolutionaries as a supporter. His open sympathy with the French Revolution in 1789 brought him into collision with reactionary forces in Spain and he was imprisoned for a short time at Granada and threatened with a trial by the Inquisition. The proceedings did not go beyond the preliminary stage and he died at age 80. (D. 1798)

John Morley

On this date in 1838, author and statesman John Morley was born in England. He was educated at Cheltenham College and Oxford. His father wanted him to become a clergyman and withdrew his financial support when Morley demurred. His plans to take the bar were interrupted by taking editorship of the rationalist Fortnightly Review in 1867, for which he also wrote. The trademark of agnostic Morley was to spell “God” with a small “g.”

His books include Burke (1867), Voltaire (1871), Rousseau (1873), On Compromise (1874), Diderot (1878), Life of Gladstone (three volumes, 1903) and Recollections (1917). He became editor of the crusading newspaper Pall Mall Gazette in 1880 and supported Prime Minister William Gladstone. Morley represented Newcastle in Parliament from 1883-95 and Montrose Burghs from 1896 to 1908. He supported parliamentary reform and Irish Home Rule and opposed the Boer War.

Known as “honest John Morley,” he was Secretary of State for India from 1905 to 1910 and Lord President of the Council from 1910 to 1914. He retired from politics to protest Britain’s entry into World War I. (D. 1923)

"Where it is a duty to worship the sun, it is pretty sure to be a crime to examine the laws of heat."

— Morley, from his 1871 book "Voltaire"