nobel-prize-winners

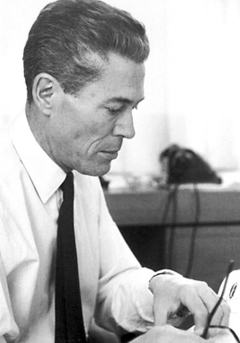

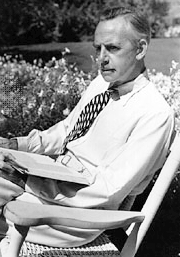

Sinclair Lewis

On this date in 1885, Harry Sinclair Lewis was born in Sauk Centre, Minn. The novelist wrote such enduring classics as Main Street (1920), Babbitt (1922), Arrowsmith (1925) and the irreverent Elmer Gantry (1927). The title character, a preacher, is portrayed as a rogue and hypocrite who steals freethinker Robert G. Ingersoll’s “Love” as his signature sermon.

Lewis’ other books include It Can’t Happen Here (1935) and The God-Seeker (1949). An unbeliever since his days at Yale, from which he graduated in 1908, Lewis was married twice and had one son. In 1930 he became the first American to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature “for his vigorous and graphic art of description and his ability to create, with wit and humour, new types of characters.” (He had refused an earlier Pulitzer Prize.)

In his autobiographical sketch for the Nobel committee, Lewis noted that although he traveled widely, he had “lived a quite unromantic and unstirring life.” He was dubbed “the conscience of his generation” by Sheldon Norman Grebstein. (D. 1951)

"It is, I think, an error to believe that there is any need of religion to make life seem worth living."

— Lewis, quoted by Will Durant in "On the Meaning of Life" (1932)

Jacques Monod

On this date in 1910, French biologist and Nobel Prize winner Jacques Lucien Monod was born in Paris to an American mother (Charlotte MacGregor Todd from Milwaukee) and a French Huguenot father, Lucien Monod, who was a painter and inspired him artistically and intellectually. In his doctoral work at the Sorbonne, Monod coined the term diauxie, meaning two growth phases, to describe different growth patterns he observed in bacteria. Monod is most famous for discovering, along with Francois Jacob and Andre Lwoff, the Lac operon feedback mechanism in living cells.

Monod received the 1963 Legion d’honneur, the highest decoration in France, for the operon theory of genetic control. The 1965 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded jointly to Monod, Jacob and Lwoff “for their discoveries concerning genetic control of enzyme and virus synthesis,” according to the Nobel Foundation website. Monod was among the first to suggest the existence of messenger RNA molecules. He’s considered one of the founders of molecular biology.

In addition to his scientific work, Monod was a talented musician and wrote on the philosophy of science. In his 1971 book, Chance and Necessity, he expounded on “an entirely non-providential view of the biological world as the mere product of chance and necessity, and proposed that the natural sciences reveal a purposeless world which entirely undercuts the tradition claims of religions.” (Cambridge University website, “Investigating Atheism.”)

In 1938 Monod married Odette Bruhl, an archaeologist and curator of the Guimet Museum in Paris. Their twin sons became a geologist and a physicist. He died of leukemia at age 66 and is buried in Cannes on the French Riviera. (D. 1976)

“As nontheists, we begin with humans not God, nature not deity.”

— Humanist Manifesto II (1973), of which Monod was one of the signatories when he was at the Institut Pasteur.

Svante August Arrhenius

On this date in 1859, physical chemist and Nobel Prize winner Svante August Arrhenius was born in Sweden. He studied at Upsala University, then under a professor in Stockholm. His 1884 thesis, on the galvanic conductivity of electrolyes, won him the first docentship at Uppsala in physical chemistry, a new branch of science. Arrhenius was also awarded a traveling fellowship and worked with scientists throughout Europe.

He was appointed a physics lecturer in 1891 at Stockholm University College. Arrhenius in 1896 was the first to identify the relationship between the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and global temperatures, with a rise in the percentage of carbon dioxide tied to a rise in temperature. His work played an important role in the emergence of modern climate science.

He won the Nobel Prize for chemical research in 1903 for originating the theory of electrolytic dissociation, or ionization. He also investigated osmosis, toxins and antitoxins. He was offered the position of chief of the Nobel Institute for Physical Chemistry, founded just for him.

Arrhenius wrote classic textbooks in his field, which were translated into many languages, and popularized science for the general public with such books as The Destinies of the Stars (1919). His wide interests in science were exemplified by his contributions to the understanding of such phenomena as the Northern Lights. In 1914 he was awarded the Faraday Medal of the Chemical Society.

During World War I he worked to get the release of many German and Austrian scientists who had been made prisoners of war. According to freethought historian Joseph McCabe, Arrhenius was a monist. However, Gordon Stein in The Encyclopedia of Unbelief (1988) said he was “a declared atheist.”

He was married twice, first to his former pupil Sofia Rudbeck (1894-96), with whom he had a son, Olof, and then to Maria Johansson (1905-27), with whom he had two daughters and a son. (D. 1927)

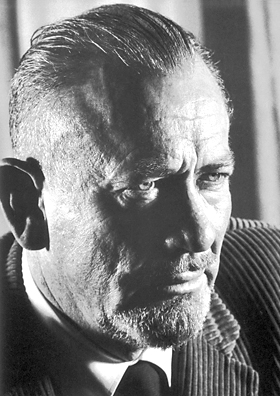

John Steinbeck

On this date in 1902, author John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. was born in Salinas, Calif. He studied marine biology at Stanford but did not graduate. His long list of humanistic novels includes the classics Of Mice and Men (1937) and The Grapes of Wrath (1939), which won a Pulitzer Prize. He also wrote Tortilla Flat (1935), The Red Pony (1937), Cannery Row (1945), East of Eden (1952) and The Winter of Our Discontent (1961), 33 books in all. He was awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize for Literature “for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humour and keen social perception.”

Asked to complete a routine medical questionnaire for his new doctor, Steinbeck did so and added a letter dated March 5, 1964: “I shall probably not change my habits very much unless incapacity forces it. I don’t think I am unique in this. Now finally, I am not religious so that I have no apprehension of a hereafter, either a hope of reward or a fear of punishment. It is not a matter of belief. It is what I feel to be true from my experience, observation and simple tissue feeling.” (Steinbeck: A Life in Letters, ed. Elaine Steinbeck, 1975)

He married Carol Henning in 1930, divorced in 1943; Gwyn Conger in 1943, divorced in 1948; and Elaine Anderson Scott in 1950, together until his death in in New York City at age 66 from congestive heart failure. He had two sons with his second wife. (D. 1968)

"Literature was not promulgated by a pale and emasculated critical priesthood singing their litanies in empty churches — nor is it a game for the cloistered elect, the tinhorn mendicants of low calorie despair."

— Steinbeck, Nobel Prize acceptance speech (1962)

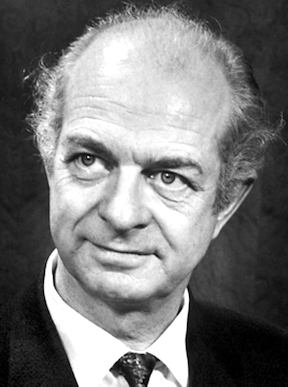

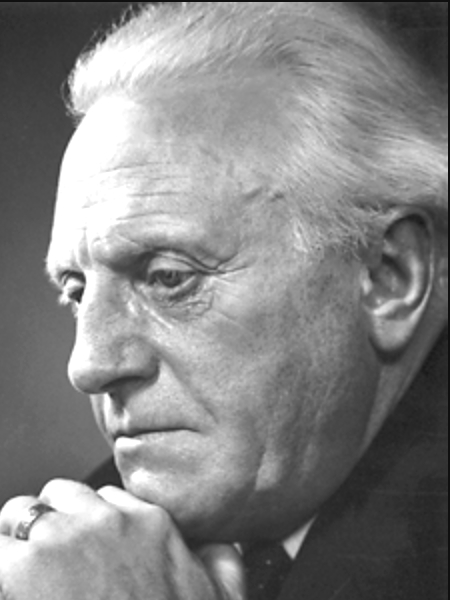

Linus Pauling

On this date in 1901, scientist and peace activist Linus Carl Pauling was born in Portland, Ore, to Herman and Lucy (Darling) Pauling. His parents, of German Lutheran background, weren’t especially active in church affairs. His father died when Pauling was 9. He studied chemistry at Oregon Agricultural College, where he met his future wife, Ava Helen Miller, with whom he would have four children. In 1922 he enrolled at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), where he earned a Ph.D. in chemistry and then joined the faculty.

He would go on to become the only person to receive two unshared Nobel Prizes: Chemistry (1954) and Peace (1962) and is considered a founding father of quantum chemistry and molecular biology. His crowning achievement was to explain the carbon bonding in molecules such as methane. He later taught at the University of California-San Diego and at Stanford University.

The advent of the nuclear age turned the Paulings into peace activists who traveled and spoke widely. They eventually joined the Unitarian Church but Pauling was not interested in theology. On “The Phil Donahue Show” in 1967, Donahue asked him if he believed in God. Pauling replied, “No, I do not.”

In accepting the Nobel Prize for Peace for 1962, he said, “The only sane policy for the world is that of abolishing war.” The award recognized his six-year campaign to persuade the U.S., Great Britain and the Soviet Union to sign a nuclear test ban. Minimizing suffering was the key to ethics, he believed. He was named Humanist of the Year by the American Humanist Association in 1961.

He died of prostate cancer at age 93 at home in Big Sur, Calif. (D. 1994)

“I am not, however, militant in my atheism. The great English theoretical physicist Paul Dirac is a militant atheist. I suppose he is interested in arguing about the existence of God. I am not.”

— Pauling, quoted in "A Lifelong Quest for Peace: A Dialogue" by Daisaku Ikeda (1992)

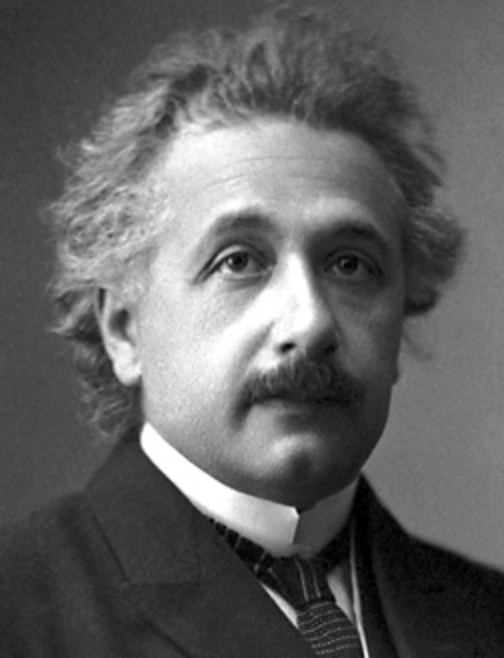

Albert Einstein

On this date in 1879, Albert Einstein was born in Ulm, Germany, to nonobservant Jewish parents. He attended a Catholic school from age 5 to 8. He completed his Ph.D. at the University of Zurich in 1909. His 1905 paper explaining the photo-electric effect — the basis of electronics — earned him the Nobel Prize in 1921. His first paper on Special Relativity Theory, also published in 1905, changed the world.

Einstein split his time and academic appointments between various European universities. After the rise of the Nazi Party, Einstein made Princeton his permanent home, becoming a U.S. citizen in 1940 after moving there in 1933 with his second wife. A pacifist during World War I, he remained a firm proponent of social justice and responsibility. Einstein played a major role in the formation of what would become International Rescue Committee. He chaired the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, which organized to alert the public to the dangers of atomic warfare.

Einstein wrote often about his views on religion and wonder at the cosmic mysteries. Confusion over his beliefs stemmed from such comments as his public statement, reported by United Press on April 25, 1929, that: “I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the orderly harmony in being, not in a God who deals with the facts and actions of men.” Einstein’s famous “God does not play dice with the Universe” metaphor — meaning nature conforms to mathematical law — fueled more confusion.

At a symposium, he advised: “In their struggle for the ethical good, teachers of religion must have the stature to give up the doctrine of a personal God, that is, give up that source of fear and hope which in the past placed such vast power in the hands of priests. In their labors they will have to avail themselves of those forces which are capable of cultivating the Good, the True, and the Beautiful in humanity itself. This is, to be sure a more difficult but an incomparably more worthy task.” (“Science, Philosophy and Religion, A Symposium,” 1941)

In a letter to philosopher Eric Gutkind dated Jan. 3, 1954, Einstein continued to reject the idea of a personal god. Although saying he was proud to be a Jew, he said he was not impressed with Judaism. “The word god is for me nothing more than the expression and product of human weaknesses, the Bible a collection of venerable, but still primitive legends which are nevertheless pretty childish.” In 2018 the “God letter” sold for almost $2.9 million following a four-minute bidding battle at Christie’s.

He married Mileva Marić in 1903 and they had two sons. They had a daughter before marriage whose fate is unclear. She was either given up for adoption or died of scarlet fever. Their son Eduard was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age 20 and spent most of the rest of his life in asylums. After divorcing in 1919, Einstein married Elsa Löwenthal that same year after having a relationship with her since 1912. She was a first cousin maternally and a second cousin paternally. She was diagnosed with heart and kidney problems and died in December 1936.

He died of an abdominal aortic aneurysm in 1955. Pathologist Thomas Stolz Harvey removed his brain without the family’s permission and preserved it in formalin before Einstein was cremated. Harvey later cut the brain into 240 blocks, took tissue samples from each block, mounted them on microscope slides and distributed the slides to some of the world’s top neuropathologists for study.

“Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hopes of reward after death. It is therefore easy to see why the churches have always fought science and persecuted its devotees."

— Einstein column headlined "Religion and Science" (New York Times Magazine, Nov. 9, 1930)

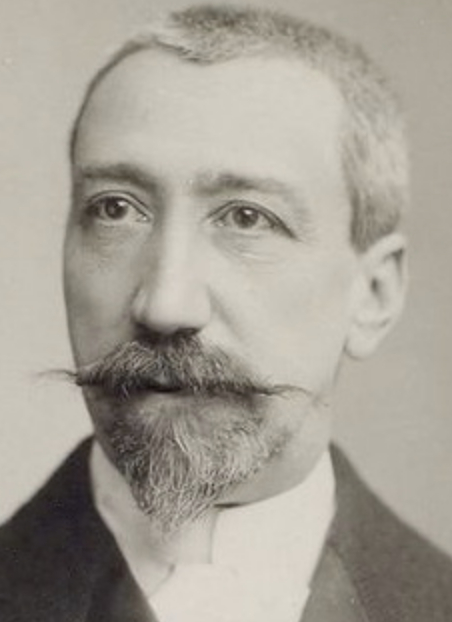

Anatole France

On this date in 1844, Anatole France (né François-Anatole Thibault) was born in Paris. A lifelong atheist, France was known for his anti-clericalism. France was a journalist, poet and writer whose breakthrough novel, The Crime of Sylvestre Bonnard (1881) centered around a skeptical scholar, perhaps modeled after the author himself. It was awarded a prize from the French Academy. France’s style, dry and ironic, was modeled in part on Voltaire and influenced by the French Enlightenment.

In 1905 he wrote a critical treatise, The Church and the Republic, which was instrumental in the campaign to disestablish the Catholic Church as the state religion. He served as an honorary president of the French National Association of Freethinkers. Penguin Island (1908) is France’s irreverent tale about a nearsighted abbot who baptizes penguins by mistake. In The Revolt of Angels (1914), France revisits Milton’s “Paradise Lost.” France depicted an angel leading a revolt after being influenced by the writings of Lucretius. With other writers, France came to the defense of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish captain falsely indicted for treason, and was a voice for reform.

His collection of aphorisms is called The Garden of Epicurus. France was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1921 “in recognition of his brilliant literary achievements, characterized as they are by a nobility of style, a profound human sympathy, grace, and a true Gallic temperament.” D. 1924.

"The thoughts of the gods are not more unchangeable than those of the men who interpret them. They advance — but they always lag behind the thoughts of men. … The Christian God was once a Jew. Now he is an anti-Semite."

— France letter to the Freethought Congress in Paris (1905), cited by Joseph McCabe in "Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists"

Steven Weinberg

On this date in 1933, Steven Weinberg was born in the Bronx, N.Y. He received his undergraduate degree in physics from Cornell University in 1954, which he attended on a scholarship. There he met his future wife, Louise Goldwasser. They married in 1954. She became a professor of law at the University of Texas. Weinberg began his graduate study at the Institute for Theoretical Physics in Copenhagen (now the Niels Bohr Institute). He completed his Ph.D. at Princeton in 1957.

In 1979 Weinberg was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics along with Abdus Salam and Sheldon Lee Glashow “for their contributions to the theory of the unified weak and electromagnetic interaction between elementary particles, including, inter alia, the prediction of the weak neutral current.” This was one of the most significant scientific advances in the second half of the 20th century.

He received many other awards, including the national Medal of Science in 1991. He was also a foreign member of the Royal Society of London. Known for his writing, Weinberg received the Lewis Thomas Prize, which is awarded to the researcher who best embodies “the scientist as poet.”

Weinberg wrote hundreds of scholarly articles and textbooks such as The Quantum Theory of Fields (three volumes: 1995, 1996, 2003) and Cosmology (2008); the more popular works The First Three Minutes: A Modern View of the Origin of the Universe (1977) and Dreams of a Final Theory (1993, which contains a chapter called “What About God?”). His collection Facing Up: Science and its Cultural Adversaries was published in 2001, and Lake Views: This World and the Universe in 2011.

Weinberg was outspoken about his lack of religion and encouraged other scientists to be more vocal in their opposition to religious ideas. He said, “As you learn more and more about the universe, you find you can understand more and more without any reference to supernatural intervention, so you lose interest in that possibility. Most scientists I know don’t care enough about religion even to call themselves atheists. And that, I think, is one of the great things about science — that it has made it possible for people not to be religious.” (Quoted in Natalie Angier, “Confessions of a Lonely Atheist,” The New York Times, Jan. 14, 2001)

He added, “The whole history of the last thousands of years has been a history of religious persecutions and wars, pogroms, jihads, crusades. I find it all very regrettable, to say the least.” Five years later at a forum at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego, he said: “Anything that we scientists can do to weaken the hold of religion should be done and may in the end be our greatest contribution to civilization.” (New York Times, Nov. 21, 2006)

In 1999 he became the first recipient of FFRF’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award, reserved for public figures who make known their dissent from religion. He began his acceptance speech: “I enjoy being at a meeting that doesn’t start with an invocation!” He said, “Nothing has been more important in the history of science than the work of Darwin and Wallace pointing out that not only the planets but even life can be understood in this naturalistic way.” More excerpts from his speech can be found here.

He died at age 88 at a hospital in Austin and was survived by his wife Louise and their daughter Elizabeth. (D. 2021)

“Religion is an insult to human dignity. With or without it you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion.”

— Weinberg address at the Conference on Cosmic Design, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington (April 1999)

Richard Feynman

On this date in 1918, Richard Phillips Feynman was born in New York City. His parents were Lithuanian Jews. Feynman, with two other scientists, won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965 for his work in quantum electrodynamics. He received his undergrad degree from MIT in 1939 and his Ph.D. from Princeton in 1942. He worked at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico as part of the nuclear Manhattan Project, then became a professor at Cornell from 1945-50.

He became professor of theoretical physics at California Institute of Technology in 1950. When Physics World polled scientists asking them to rank the greatest physicists, Feynman was rated seventh, behind Galileo. He was a writer and personality as well. His first popular book was Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!: Adventures of a Curious Character (1985). His academic classic was the three-volume Lectures on Physics.

His sister Joan once said, “If you wanted to have a good party, you had Richard there.” (Los Angeles Times, Dec. 2, 2001.) In What Do You Care What Other People Think?: Further Adventures of a Curious Character (1988), Feynman said he gradually came to disbelieve the whole religion of Judaism as a teenager.

Feynman was first treated for stomach cancer in 1978. He made headlines after being appointed to a commission investigating the 1986 Challenger shuttle disaster, when he figured out and demonstrated what went wrong with the O-rings. (D. 1988)

PHOTO: Nobel Foundation

“One time, when I wasn’t there, somebody nominated me for president of the youth center. The elders began getting nervous, because I was an avowed atheist by that time.”

— "What Do You Care What Other People Think?: Further Adventures of a Curious Character" (1988)

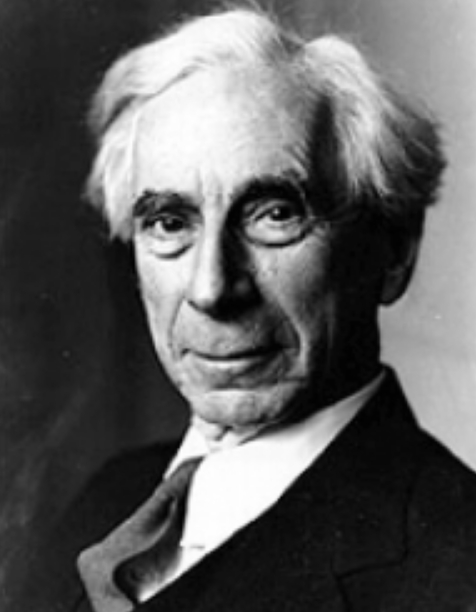

Bertrand Russell

On this date in 1872, Bertrand Arthur William Russell was born in England. “A good world needs knowledge, kindliness, and courage; it does not need a regretful hankering after the past, or a fettering of the free intelligence by the words uttered long ago by ignorant men,” Russell wrote. “Bertie” to friends, Russell, during his 97 years, did all he could to add to human knowledge and to inspire kindness.

His second wife, Dora Black, called him “enchantingly ugly.” An attorney who won a suit to void Russell’s appointment to the philosophy department at the College of the City of New York in 1940 because of his liberal views, described Russell as “lecherous, libidinous, lustful, venerous, erotomaniac, aphrodisiac, irreverent, narrow-minded, untruthful and bereft of moral fiber.”

“What I wish at bottom is to become a saint,” Russell once admitted, but he couldn’t help being pleased by the label “aphrodisiac.” The mathematician (who called his first encounter with Euclid “as dazzling as first love”) philosopher and social activist published 75 books.

He launched headlong into a life of radicalism in his 40s as a pacifist opposing World War I. He liked to recount his experience in prison, where he was sentenced for his pacifism, and in his autobiography wrote: “I was much cheered on my arrival by the warden at the gate, who had to take particulars about me. He asked my religion, and I replied ‘agnostic.’ He asked how to spell it, and remarked with a sigh, ‘Well, there are many religions, but I suppose they all worship the same God.’ This remark kept me cheerful for about a week.”

He spent his last years courageously working for nuclear disarmament. In “The Faith of a Rationalist,” broadcast by the BBC in 1953, Russell observed: “Cruel men believe in a cruel God and use their belief to excuse their cruelty. Only kindly men believe in a kindly God, and they would be kindly in any case.” One of his maxims was “Never try to discourage thinking, for you are sure to succeed.” Russell won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950 “in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought.” (D. 1970)

"I believe that when I die I shall rot, and nothing of my ego will survive. I am not young, and I love life. But I should scorn to shiver with terror at the thought of annihilation. Happiness is nonetheless true happiness because it must come to an end, nor do thought and love lose their value because they are not everlasting."— Russell, "What I Believe" (1925), reprinted in "Why I Am Not a Christian" (1957)

Pär Lagerkvist

On this day in 1891, Pär Fabian Lagerkvist, who became a Nobel laureate, was born in Växjö, Småland, a rural province in southern Sweden. After a year of study at the University of Uppsala, Lagerkvist traveled to Paris in 1912, where he immersed himself in the modern art movement, which ultimately influenced his early writings. He abandoned realism and instead followed the surreal, symbolic example of the playwright August Strindberg.

Lagerkvist described himself as “a believer without faith — a religious atheist.” (Contemporary Authors Online) Much of his work was concerned with religious themes, such as the conflict between Christianity and technology, the meaning of life and the relationship between individuals and God.

Several of his later works, such as the novels Barabbas (1950) and Herod and Mariamne (1967) deal with biblical characters and settings in a fictional context. Others deal with religious mythology, such as 1960’s The Death of Ahasuerus, about the Christian mythological figure commonly known as the “Wandering Jew.” Many critics have said that Lagerkvist’s characters, like himself, are doubters who want to believe but lack faith.

In 1951 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Lagerkvist did not answer questions about his personal life and discouraged the production of biographies during his lifetime. His second wife, Elaine Sandel, died in 1967. They had three children, Ulf, Bengt and Elin. He died at age 83 in Stockholm. (D. 1974)

"If you believe in god and no god exists

then your belief is an even greater wonder.

Then it is really something inconceivably great.Why should a being lie down there in the darkness crying to someone who does not exist?

Why should that be?

There is no one who hears when someone cries in the darkness. But why does that cry exist?"— Lagerkvist, "Aftonland," translated by W. H. Auden and Leif Sjöberg in "Evening Land" (1975)

Pablo Neruda

On this date in 1904, Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto was born in Parral, Chile. His first poems were published under the pen name Pablo Neruda in 1918 in a Santiago magazine. His first widely read book, Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair was published in 1924. In 1927 he was made Chilean honorary consul to Rangoon, Burma (now Myanmar), in honor of his accomplishments in poetry.

His work as an official representative of Chile continued in Spain, where he became involved with the republican cause. He was recalled to Chile in 1937. In 1945 he joined the Communist Party and was elected to the Senate, fleeing the country three years later when the party was banned by the government.

Neruda continued to travel the world, first in exile and after he was allowed to return to Chile in 1952. During this period, much of his poetry was political in nature, including the famous “Canto General” (General Song), an epic of the New World, which connected the Americas’ origins and conquests to their current political state.

Neruda was a confirmed communist and was awarded the Stalin Peace Prize and Lenin Peace Prize in 1953. He stated some philosophical views in his poetry, describing himself in his poem “A Dog Has Died” as “I, the materialist, who never believed / in any promised heaven in the sky / for any human being.” He ran for president of Chile in 1969 but withdrew in favor of Salvador Allende. He was diagnosed with cancer in 1970 but went on to represent Chile as ambassador to France.

In 1971 he received the Nobel Prize in Literature. He survived Allende by only 12 days. Eight books of his poetry, which he had planned on publishing on his 70th birthday, were published posthumously. (D. 1973)

“Like his father, Neruda was an atheist, and he felt an intuitive aversion to the mystical religions of Asia, which was later confirmed by his embrace of Communism, with its doctrinaire rejection of all religion.”

— Jamie James, "Pablo Neruda's Life as a Struggling Poet in Sri Lanka," Literary Hub (June 3, 2019)

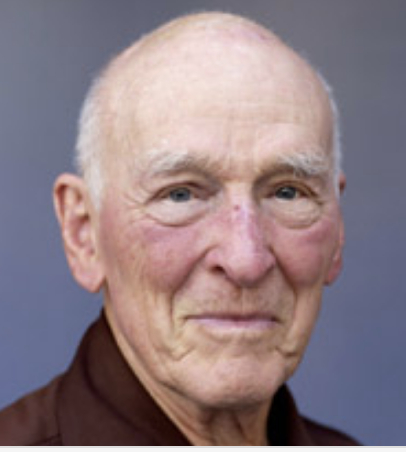

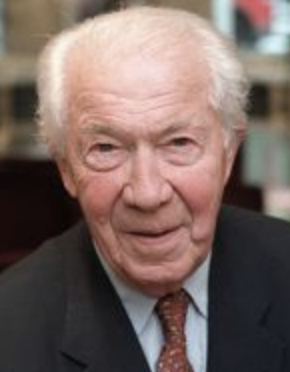

Paul D. Boyer

On this date in 1918, molecular biochemist Paul D. Boyer was born in Provo, Utah, the middle child in a family of six in a Mormon home. His mother’s death from Addison’s disease when he was 15 awakened his interest in studying biochemistry. He became a “deacon” in the Mormon church at age 12 and graduated from Brigham Young University, where he met his future wife Lyda Whicker (they would have three children). His pursuit of science during graduate studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison altered his religious perspective. He earned his doctorate in 1943.

After moving to Stanford University to do postdoctoral research for a war project, he and Lyda stopped going to Mormon meetings. By the time he was 25 he had “slipped over from agnostic to atheist,” he told Freethought Radio in 2007, and Lyda also professed her atheism. In 1955 he went to Sweden on a Guggenheim Fellowship. Boyer spent 17 years as a faculty member at the University of Minnesota. He continued his work at UCLA in 1963 and became director of the newly created Molecular Biology Institute there in 1965. He would stay at UCLA for over half a century, studying enzymes, the proteins involved in biochemical processes in animal and plant cells.

Boyer shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1997 with John Waller and Jens Skow “for their elucidation of the enzymatic mechanism underlying the synthesis of adenosine triphosphate.” As his New York Times obituary later put it, he shared the prize “for his contributions to understanding the way all organisms get energy from their environments and process it to sustain life and fuel their activities.”

Boyer had pointed out that “belief in God and in a Hereafter dropped considerably as the level of scientific achievement increased.” In his Nobel autobiography he called himself as a “devout atheist” and added, “I wonder if in the United States we will ever reach the day when the man-made concept of a God will not appear on our money, and for political survival must be invoked by those who seek to represent us in our democracy.”

He became an advocate of death with dignity after the illness and death of his son Douglas in 2001. Boyer was an FFRF Life Member who spoke at the 2002 national convention in San Diego and outlined his “path to atheism” in a 2004 Freethought Today essay. He died less than two months shy of his 100th birthday. (D. 2018)

PHOTO by Brent Nicastro.

"My views have changed from a belief that my prayers were heard to clear atheism. … Over and over, expanding scientific knowledge has shown religious claims to be false.”

“None of the beliefs in gods has any merit."

— Boyer, "A Path to Atheism," Freethought Today (March 2004)

Paul Dirac

On this date in 1902, Paul Dirac, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist, was born in Bristol, England. Dirac received his undergraduate degree in electrical engineering in 1921 and his master’s in mathematics in 1923, both from the University of Bristol. He went on to earn a Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge in 1926, studying quantum mechanics and the theory of general relativity. He introduced an equation in 1928 which became known as the Dirac Equation. His equation, along with many other advances, implied the existence of anti-matter. Dirac and Erwin Schrodinger won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1933 for “the discovery of new productive forms of atomic theory.”

Dirac married Margit Wigner in 1937 and they had four children. He was known for being extremely modest — he tended to name his discoveries after others instead of himself. He chose to give all of the proceeds from his book Directions in Physics (1978) to create a lecture series at the University of New South Wales in Kensington, Australia. He was a faculty member at the University of Cambridge, where he held the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics, and at the University of Miami and Florida State University.

A memorial for Dirac was unveiled in 1995 in Westminster Abbey. The dean of Westminster, Edward Carpenter, had initially refused to allow the memorial to be created, calling Dirac “anti-Christian” but relented after five years.

Along with receiving the Nobel Prize, he won the Copley Medal and the Max Planck Medal in 1952 and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1930. Many awards have been named after him, including the Paul Dirac Medal and Prize awarded by the Institute of Physics, of which Stephen Hawking was a recipient. (D. 1984)

"If we are honest — and scientists have to be — we must admit that religion is a jumble of false assertions, with no basis in reality. The very idea of God is a product of the human imagination. If religion is still being taught, it is by no means because its ideas still convince us, but simply because some of us want to keep the lower classes quiet."

— Excerpt of Dirac's criticism of the political purposes of religion at the Fifth Solvay International Conference (October 1927)

Jane Addams

On this date in 1860, Jane Addams was born, the eighth child of a prosperous family in Cedarville, Ill. Her mother died while pregnant when Addams was 2. Her businessman father, Quaker by conviction but not affiliation, served for many years in the state Senate. Addams entered Rockford Female Seminary at age 17, intending to pursue a medical career.

Her plans changed after she developed health problems of her own and her father died from appendicitis while vacationing with his second wife at a Green Bay hotel. She inherited $50,000 in 1881, a considerable sum at the time.

She and classmate Ellen Gate Starr, with whom she had a romantic relationship, opened a settlement home in Chicago in 1889, expanding services for the working-class poor to include a girls’ home, nursery and other amenities. Hull House was secular by Addams’ decree. She documented social conditions, worked with reformers and radicals of every stripe and wrote articles on everything from suffrage to prostitution.

She co-founded the Woman’s Peace Party in 1915 and was elected national chair. It eventually became the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. She was intimately involved with the founding of sociology as an academic field in the U.S. The Jane Addams College of Social Work is a professional school at the University of Illinois in Chicago.

Addams won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931. Although she credited Jesus in her address, “A Challenge to the Contemporary Church,” she denounced the church fathers very firmly in it: “The very word woman in the writings of the church fathers stood for the basest temptations.” While she remained a member of a Presbyterian church, Addams regularly attended and sometimes lectured at Unitarian and Ethical Society events and had a close relationship with members of the Jewish community.

Addams had a long domestic partnership with Mary Rozet Smith, who was wealthy and supported Addams’ work at Hull House and elsewhere. They were together for 40 years until 1934, when Smith died of pneumonia. Addams, who suffered a heart attack in 1926, died of cancer in 1935.

"A wise man has told us that ‘men are once for all so made that they prefer a rational world to believe in and live in.’ "

— Addams, "Twenty Years at Hull-House" (1912)

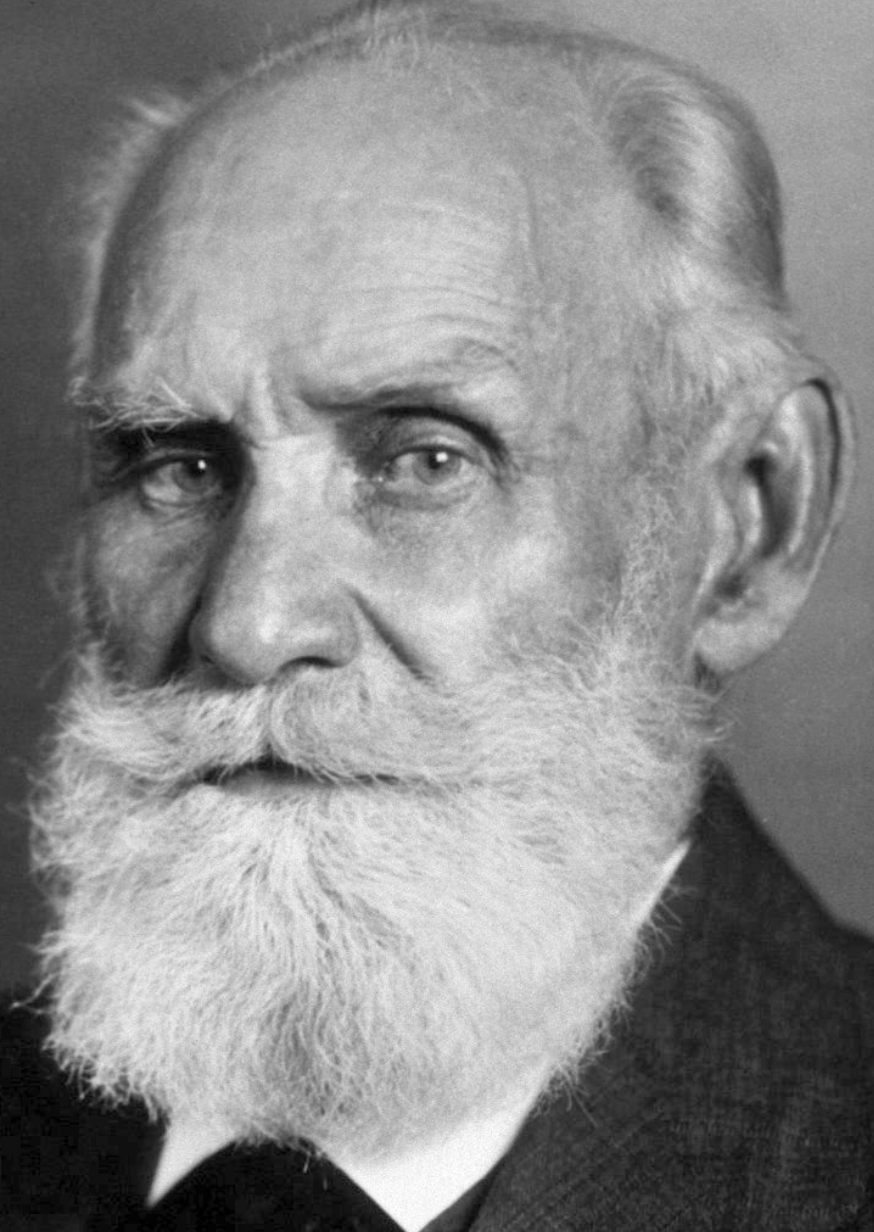

Ivan Pavlov

On this date in 1849, Ivan Petrovich Pavlov was born in Ryazan, Russia. He enrolled in Ryazan Ecclesiastical Seminary in the 1860s. In 1870 he dropped out in order to study natural sciences at the University of St. Petersburg. He graduated in 1875 and went on to attend the Academy of Medical Surgery. Pavlov became a professor of pharmacology at the Military Medical Academy in 1890 and director of the department of physiology at the Institute of Experimental Medicine in 1891, where he studied the physiology of the digestive system, often using dogs as research subjects.

He wrote books about his research, including Work of the Digestive Glands (1897). In 1904 he earned the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for his work with digestive organs. Pavlov married his wife, Serafima, in 1881.

Despite Pavlov’s influential research on the digestive system, he is most famous for his discovery of classical conditioning: teaching an animal to associate a reflex with an unrelated stimulus. Pavlov made the discovery while researching the salivary glands of dogs, after he noticed that dogs salivated when they anticipated food in addition to when they began eating. This led him to condition the dogs to begin salivating when they saw or heard a variety of stimuli, most famously, bells. He accomplished this by ringing a bell every time he fed the dogs, making them associate bells with food.

Pavlov described himself as an atheist who lost his faith when he was a seminary student. “In regard to my religiosity, my belief in God, my church attendance, there is no truth in it; it is sheer fantasy,” Pavlov told his student Evgenii Mikhailovich Kreps in the 1920s, according to the article “Pavlov’s Religious Orientation” by George Windholz (1986). Windholz also quoted Pavlov as saying, “There are weak people over whom religion has power. The strong ones — yes, the strong ones — can become thorough rationalists, relying only upon knowledge, but the weak ones are unable to do this.” D. 1936.

"Humans saved themselves by creating religion, which enabled them to maintain themselves somehow, to survive in the midst of an uncompromising, all-powerful nature. It is a very basic instinct that is thoroughly rooted in human nature."

— Pavlov, quoted in "Pavlov's Religious Orientation," Vol. 25 of the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 1986

Christian de Duve

On this date in 1917, Nobel Prize-winning scientist Christian de Duve was born to Belgian parents in Surrey, England. He later moved to Belgium and during World War II served as a medic in the Belgian Army. He received his Ph.D. in chemistry in 1945 from the Catholic University of Leuven. His thesis focused on insulin, the chemical that regulates blood sugar and when not produced causes diabetes. He married Janine Herman in 1943. They had had two sons, Thierry and Alain, and two daughters, Anne and Françoise.

De Duve became a professor at the Catholic University of Leuven in 1947 and in 1962 also became associated with Rockefeller Foundation laboratories in New York City. His work focused on subcellular biochemistry, cell biology and the origin of life.

He discovered two types of cell organelles: peroxisomes and lysosomes. His research furthered understanding of genetic disorders such as Tay-Sachs disease. De Duve shared the 1974 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine with Albert Claude and George Palade for their work on cell structure. The three are recognized as the fathers of the field of modern cell biology.

While raised Catholic, de Duve tended toward agnosticism if not outright atheism. He strongly supported biological evolution and dismissed creation science and intelligent design, as explicitly stated in his last book, Genetics of Original Sin: The Impact of Natural Selection on the Future of Humanity (2010). In declining health at age 95, he chose to end his life with the aid of two doctors. Euthanasia is legal in Belgium. (D. 2013)

"It would be an exaggeration to say I'm not afraid of death, but I'm not afraid of what comes after, because I'm not a believer."

— De Duve, explaining his choice to die using euthanasia (New York Times, May 6, 2013)

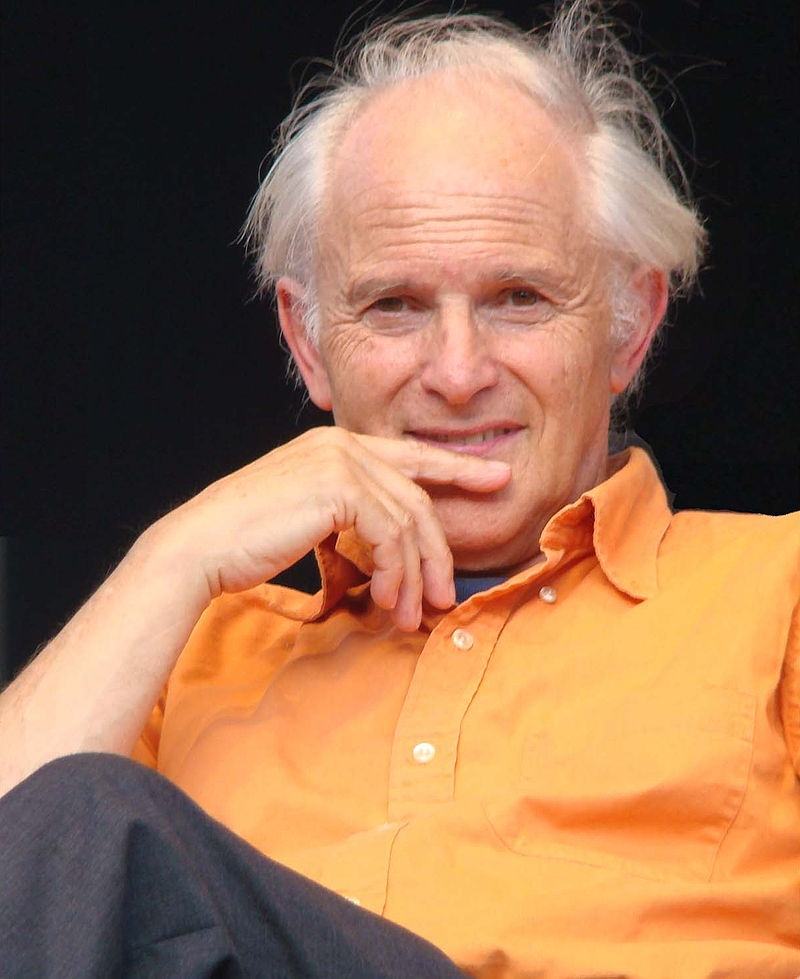

Harry Kroto

On this date in 1939, chemist Harold Walter “Harry” Kroto (né Krotoschiner) was born in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, England. His parents were both German but had to leave Berlin in 1937 because his father was Jewish. Kroto attended Sheffield University to study chemistry, graduating with honors in 1961 and receiving his Ph.D. in 1964. He did postdoctoral research at the National Research Council in Canada and Bell Laboratories in the U.S.

He returned to England in 1967 to teach at the University of Sussex and research carbon chains in interstellar space. Aware of the laser spectroscopy work being done by Richard Smalley and Robert Curl at Rice University in Texas, Kroto contacted them and suggested they use the Rice apparatus to simulate the carbon chemistry that occurs in the atmosphere of a carbon star. The experiment supported their theory and revealed an unexpected result, the existence of a new molecule, the C60 species, aka buckminsterfullerene (buckyballs). The discovery earned Curl, Kroto and Smalley the shared Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1996. “Sir” soon preceded his name when he was knighted that year.

In 2004 he joined the faculty at Florida State University as a professor of chemistry, where he continued his work on carbon and spearheaded the development of GEOSET (Global Educational Outreach for Science, Engineering and Technology). GEOSET is a growing online cache of video teaching modules that are available for free.

In 1963 he married Margaret Henrietta Hunter, also a student of the University of Sheffield. They had two sons, Stephen and David. A humanist and professed atheist, he once joked, “The only mistake Bernie Madoff made was to promise returns in this life.” (According to A.C. Grayling in The Guardian, July 1, 2009)

He died at age 76 in Lewes, East Sussex, from complications of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. (D. 2016)

PHOTO: By Pd1000 under CC 3.0.

“I am a devout atheist — nothing else makes any sense to me and I must admit to being bewildered by those, who in the face of what appears so obvious, still believe in a mystical creator.”

— From Kroto's Nobel Prize autobiography (1996)

Eugene O’Neill

On this date in 1888, Eugene O’Neill was born in New York City in a hotel on Broadway, the third son of popular actor James O’Neill. As a youngster he traveled with his father, then was sent to a Catholic boarding school. O’Neill entered Princeton in 1906. After he was expelled he set off on adventures prospecting for gold in Honduras, working as a sailor and a variety of other jobs. While recovering from a bout of tuberculosis, O’Neill, influenced by his reading of Ibsen and other dramatists, determined to become a playwright.

He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1936 and four Pulitzer Prizes for Beyond the Horizon (1920), Anna Christie (1922), Strange Interlude (1928) and Long Day’s Journey into Night, written in 1939 but awarded posthumously in 1957. Some of his other works include Mourning Becomes Electra (1931), Ah, Wilderness! (1933), The Iceman Cometh (1936) and A Moon for the Misbegotten (1943).

O’Neill had three wives and three children before dying at age 65 after years of poor health exacerbated by alcoholism. He died in Room 401 in the Sheraton Hotel in Boston. According to biographer Louis Scheaffer, his whispered last words were “I knew it. I knew it. Born in a goddamn hotel room and dying in a hotel room.” (D. 1953)

"When I’m dying, don’t let a priest or Protestant minister or Salvation Army captain near me. Let me die in dignity. Keep it as simple and brief as possible. No fuss, no man of God there. If there is a God, I’ll see him and we’ll talk things over."

— O'Neill's instructions to his wife Carlotta, "O'Neill: Son and Artist" by Louis Scheaffer (2002)

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar

On this date in 1910, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar was born in Lahore, now in Pakistan but at the time a part of British India. He earned a B.S. with honors in physics from Presidency College in India in 1930 and a Ph.D. in physics from Cambridge University in England in 1933. After his graduation, Chandrasekhar was awarded a Prize Fellowship at Trinity College from 1933 to 1937. He worked as a research associate and professor at the University of Chicago from 1937 to 1995, and became an American citizen in 1953. He married Lalitha Doraiswamy in 1936.

Chandrasekhar was an astrophysicist who made influential discoveries about white dwarf stars in 1930 when he was only 20. He is known for discovering the Chandrasekhar limit. He found that stars with masses below the Chandrasekhar limit form white dwarfs after they collapse, but stars with masses above the limit continue collapsing. His studies of stellar evolution were influential in the discovery of black holes.

He won the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physics with William Fowler for their work with stellar structure and evolution. He published 10 books, including Introduction to the Study of Stellar Structure (1939), Principles of Stellar Dynamics (1942) and The Mathematical Theory of Black Holes (1983).

Chandrasekhar was the nephew of C. V. Raman, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1930. He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1953. A vegetarian, he died of a heart attack at age 84 at the University of Chicago Hospital, 20 years after his first heart attack. His wife died at age 102 in 2013. (D. 1995)

"I am not religious in any sense; in fact, I consider myself an atheist."

— Chandrasekhar, quoted in "Chandra: A Biography of S. Chandrasekhar" by Kameshwar Wali (1991)

Klas Pontus Arnoldson

On this date in 1844, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Klas Pontus Arnoldson was born in Goteburg, Sweden. He left school after his father died at age 16 and worked for the Swedish State Railways for two decades. He was elected to the Riksdag, the Swedish parliament, from 1882-87, where he championed expansion of the franchise, anti-militarism and political neutrality for Sweden. He founded the Swedish Peace and Arbitration Society in 1883 and edited several journals.

He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1908 for his pacifist work, especially during the 1895 dissolution of the union between Norway and Sweden, in which he controversially sided with Norway. After concentrating on largely journalistic writing, Arnoldson wrote several major works during his last three decades, including Religion in the Light of Research (1891). D. 1916.

“Familiar with the humanistic tenets of religious movements originating in the nineteenth century in Great Britain and in the New England section of the United States, he decried fanatic dogmatism and espoused essentially Unitarian views on truth, tolerance, freedom of the individual conscience, freedom of thought, and human perfectability.”

— from Arnoldson's Nobel Prize biography

Marie Curie

On this date in 1867, two-time Nobel Prize winner Maria Salomea Curie, née Sklodowska, was born in Warsaw, Poland. Her father was an atheist and her mother was Catholic. The deaths of her mother and sister caused her to abandon Catholicism and become agnostic as a teen. (Marie Curie by Robert Reid, 1978.)

Curie moved to Paris to study at the Sorbonne in 1891, got her degree in math and married Pierre Curie in a civil ceremony. The couple had two daughters, Irène and Ève. Curie broke many barriers for her sex, becoming the first European woman to earn a science doctorate and the first to be awarded a Nobel Prize.

She and Pierre and physicist Henri Becquerel were jointly awarded the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics “for their joint researches on the radiation phenomena discovered by Professor Henri Becquerel.” She coined the very word “radioactive.” She won the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for “the discovery of the elements radium and polonium, by the isolation of radium and the study of the nature and compounds of this remarkable element.”

Pierre died tragically in 1906 at age 46 when he slipped in the street and a horse-drawn cart ran over his head. Curie took over his professorship of general physics at the University of Paris, winning another first for women. She was also the first person and only woman to win a Nobel Prize twice and the only person to win a Nobel in two different scientific fields.

Yet in 1911 the French Academy of Sciences failed in a close vote to elect her as a member. Before the election, she was vilified by the right-wing press as a foreigner and atheist. Not until 1962 would a woman, ironically a doctoral student of Curie’s, be elected.

She became director of the Curie Laboratory in the Radium Institute of the University of Paris in 1914 and spent much of the rest of her life pursuing the goal of “easing human suffering.” Her daughter Irène and her husband Frédéric Joliot-Curie were jointly awarded the 1935 Nobel Prize for Physics for synthesizing new elements.

Her daughter Ève in her memoir “Mme. Curie” (1937) described all family members as rationalists. Curie wrote in 1923 that Eugène Curie, her physician father-in-law, was “a free thinker and an anticlerical, he did not have his sons baptized, nor did he have them practice any form of religion.”

Curie died at age 66 of aplastic anemia attributed to radiation exposure. In 1995 she became the first woman to be entombed on her own merits in the Panthéon in Paris. (D. 1934)

"Pierre belonged to no religion and I did not practice any."— Marie Curie, "Pierre Curie" (1923)

Albert Camus

On this date in 1913, Nobel Prize-winning writer Albert Camus was born in Mondovi, Algeria, to immigrant parents: a French father and a Spanish mother. After his father died during World War I in 1914, his family was left in extreme poverty. He excelled in athletics and academics and entered the University of Algiers to study, although a serious bout of tuberculosis cut short his studies. He joined the anti-fascist movement in 1934 but was soon expelled from the Algerian Communist Party as a “Trotskyist.”

Camus wrote for a socialist paper in the late 1930s, chronicling the plight of the poor. In 1940 he went to Paris, fled after the German invasion, returned to Algeria, was advised to leave and at age 25 found himself back in Paris. Camus joined the Resistance and after liberation was a columnist for the newspaper Combat.

His major writings include the essay “The Myth of Sisyphus” 1942, L’Etranger (The Stranger) 1942, La Peste (The Plague) 1947, which includes a priest character who insists a plague was sent as punishment from God, La Chute (The Fall) 1956 and L’Exile et le Royaume (Exile and the Kingdom) 1957, the year he won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Camus was a pioneer of absurdist philosophy and literature and became a nonbeliever after being raised Catholic. He married Simone Hié in 1934. Soon after they divorced in 1940, he married pianist and mathematician Francine Faure, who gave birth to twins Catherine and Jean in 1945. Camus died at age 46 in an auto accident. (D. 1960)

"[Camus’] anti-Christianity is one of the most absolute of modern times."

— Martin Seymour-Smith, "Who's Who in Twentieth-Century Literature" (1976)

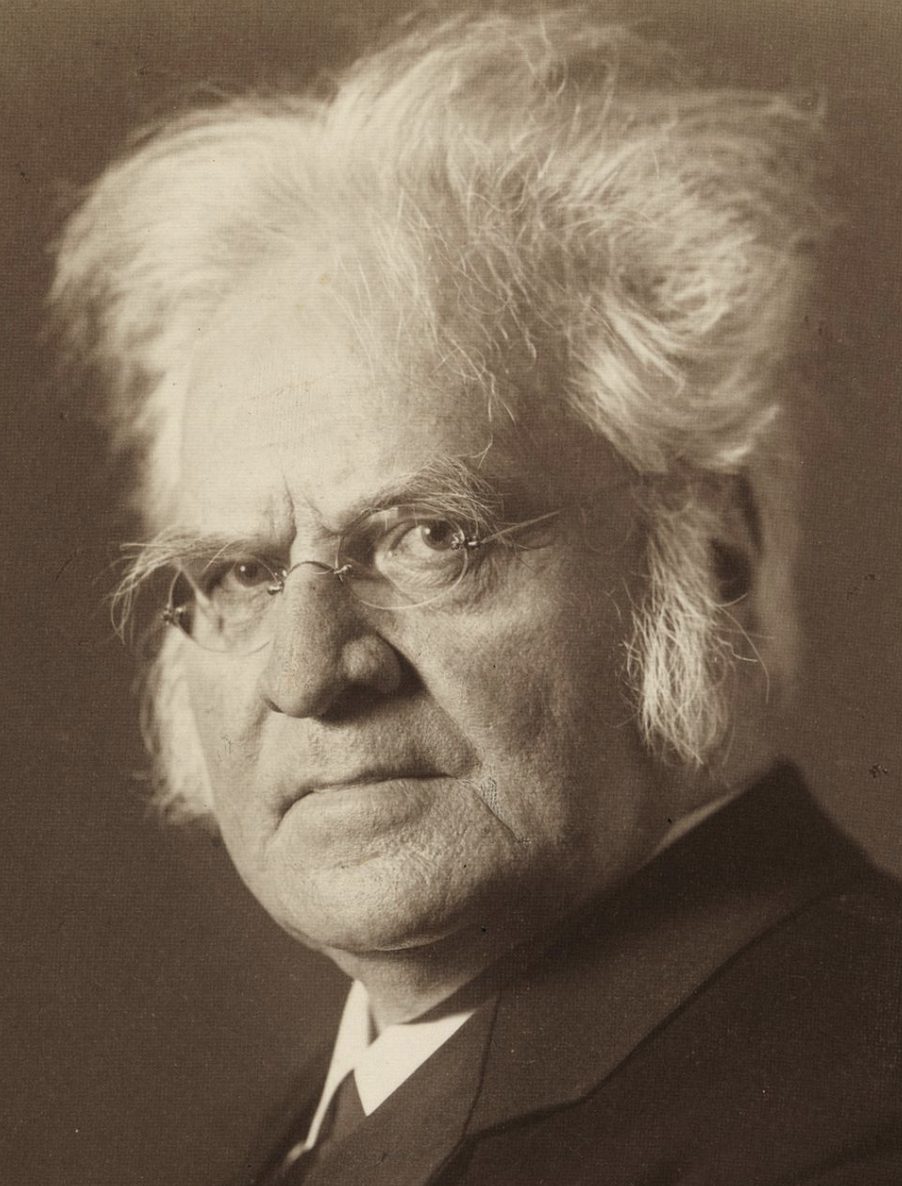

Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson

On this date in 1832, Nobel Laureate Bjørnstjerne Martinius Bjørnson was born in Norway. The son of a Lutheran minister, Bjørnson was a journalist, then a playwright and novelist who also directed theater. He wrote the first realistic contemporary play, with Ibsen following suit. Bjørnson’s plays were the first Norwegian works to be performed outside Scandinavia. Standing next to Ibsen in acclaim, he became what freethought historian Joseph McCabe termed “an aggressive Agnostic” in 1875 after reading Herbert Spencer.

His story “Dust” (1882), showed the harm of religious influence. Bjørnson wrote “Whence Came the Miracles of the New Testament?” (1882), translated Ingersoll and was an honorary associate of the Rationalist Press Association. For three decades he was a leader of Norwegian republicans. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1903 “as a tribute to his noble, magnificent and versatile poetry.” (D. 1910)