December 8

Baron d’Holbach

On this date in 1723, Paul Henri Baron von Holbach, one of the Enlightenment’s most passionate atheists, was born in Edesheim, Germany, into a Catholic family. An uncle who became a wealthy nobleman brought Holbach to Paris when he was 12, educated him and left him his fortune. Holbach studied law in Holland, returned to Paris and inherited more wealth. Holbach befriended the Encyclopedists, including Denis Diderot, and his Parisian home became a hub of the Enlightenment.

Holbach wrote several articles for the Encyclopedia and also translated German scholars, then began writing his philosophical pieces in secret. He did not sign his name to these atheistic works, so, although some were ordered to be burned in France, he was spared prosecution. He eventually inspired a “Holbachian” movement of anticlericalism and philosophical materialism.

Holbach’s writings include a series of works published in 1770 inquiring into the historicity of Jesus, the saints and other freethought subjects. Christianity Unveiled was published in 1766, The Holy Disease in 1768, System of Nature in 1770 and Le Bon sens (Common Sense) in 1772, followed by several political and moral treatises. In Common Sense, Holbach wrote that “Religion is a mere castle in the air. Theology is ignorance of natural causes; a tissue of fallacies and contradictions.”

He believed “Knowledge, Reason, and Liberty, can alone reform and make men happier.” He optimistically predicted “If the ignorance of nature gave birth to the gods, knowledge of nature is destined to destroy them.” Holbach translated and adapted many major deistic English writings. He particularly criticized Catholicism as an obstacle to freedom and the common good. (D. 1789)

“Savage and furious nations, perpetually at war, adore, under divers names, some God, conformable to their ideas, that is to say, cruel, carnivorous, selfish, blood-thirsty. We find, in all the religions, ‘a God of armies,’ a ‘jealous God,’ an ‘avenging God,’ a ‘destroying God,’ a ‘God,’ who is pleased with carnage, and whom his worshippers consider it a duty to serve. Lambs, bulls, children, men, and women, are sacrificed to him. Zealous servants of this barbarous God think themselves obliged even to offer up themselves as a sacrifice to him.”

— Baron d'Holbach, "Common Sense" (1772)

James Thurber

On this date in 1894, humorist and cartoonist James Grover Thurber was born in Columbus, Ohio. He called his mother — who once impersonated a cripple at a faith-healing rally in order to leap up and call herself cured — a “born comedienne.” Thurber was partially blinded as a young boy when his brother accidentally shot an arrow into his eye. He could not serve in World War I but attended Ohio State University from 1913-18. He was a code clerk in Washington, D.C., and at the U.S. Embassy in Paris, then became a newspaperman.

He wrote for the Chicago Tribune from Paris and joined the Evening Post staff in New York in 1927, then The New Yorker. He wrote a satire of psychoanalysis, Is Sex Necessary (1929) with E.B. White, featuring his drawings, which immediately became popular. Thurber’s eyesight worsened in the 1930s and 1940s. His books included My Life and Hard Times (1933), Fables for Our Time (“Early to rise and early to bed makes a male healthy and wealthy and dead”) and two modern fairy tales for children in the 1950s.

His most famous story was “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty,” about a meek husband with an absurdly rich inner fantasy life, which spawned a 1947 movie starring Danny Kaye. Thurber once said, “The wit makes fun of other persons; the satirist makes fun of the world; the humorist makes fun of himself, but in so doing, he identifies himself with people — that is, people everywhere, not for the purpose of taking them apart, but simply revealing their true nature.”

His biographer Harrison Kinney wrote, “Thurber had never allowed his probing, restless mind to settle on any single theological insurance policy concerning the possibilities of the hereafter. He remained an agnostic.” (Cited in Final Chapters: How Famous Authors Died by Jim Bernhard, 2015)

He was married to Althea Addams Thurber from 1925-35. Their daughter Rosemary was born in 1931. He was married to Helen Wismer Thurber from 1935 until his death at age 66 from pneumonia several weeks after being stricken with a cerebral blood clot. (D. 1961)

“If I have any beliefs about immortality, it is that certain dogs I have known will go to heaven, and very, very few persons.”

— Attributed to Thurber but unsourced

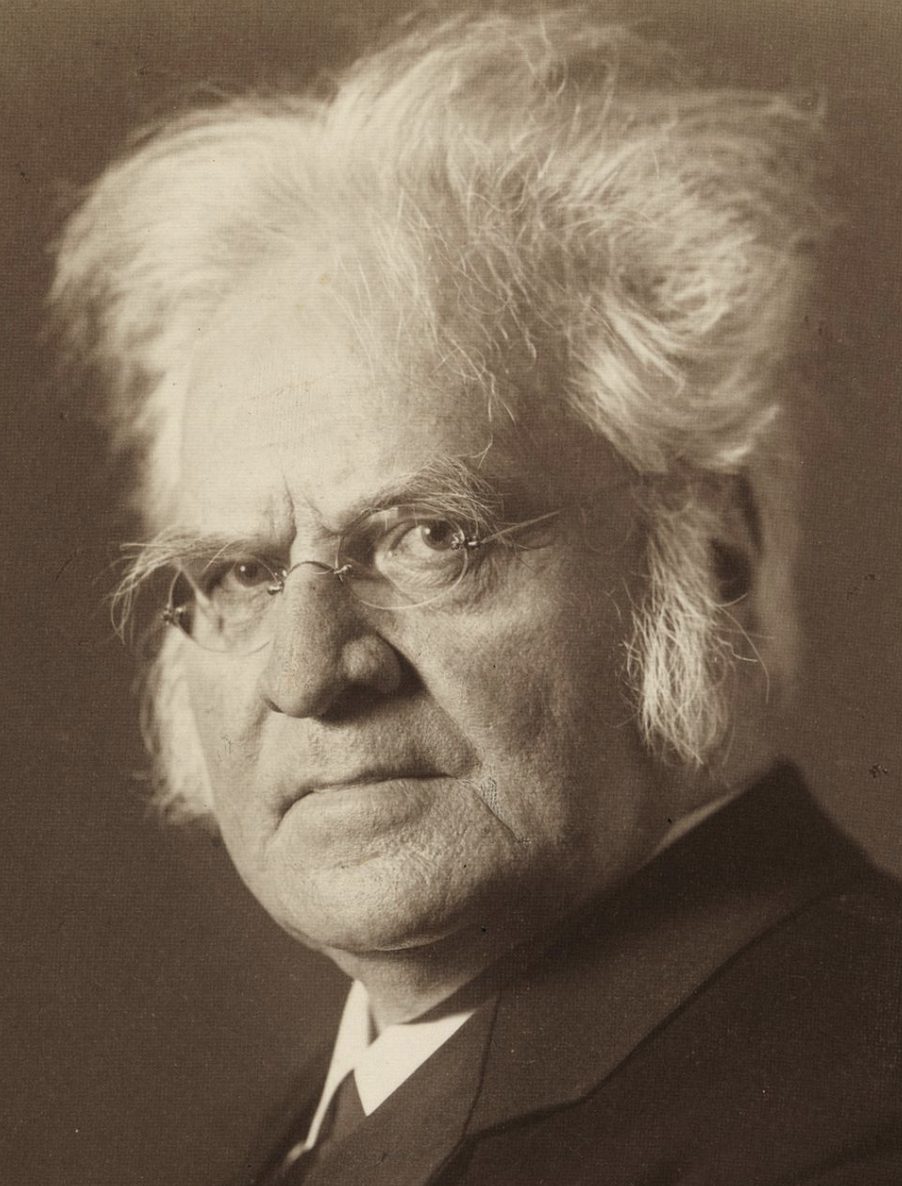

Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson

On this date in 1832, Nobel Laureate Bjørnstjerne Martinius Bjørnson was born in Norway. The son of a Lutheran minister, Bjørnson was a journalist, then a playwright and novelist who also directed theater. He wrote the first realistic contemporary play, with Ibsen following suit. Bjørnson’s plays were the first Norwegian works to be performed outside Scandinavia. Standing next to Ibsen in acclaim, he became what freethought historian Joseph McCabe termed “an aggressive Agnostic” in 1875 after reading Herbert Spencer.

His story “Dust” (1882), showed the harm of religious influence. Bjørnson wrote “Whence Came the Miracles of the New Testament?” (1882), translated Ingersoll and was an honorary associate of the Rationalist Press Association. For three decades he was a leader of Norwegian republicans. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1903 “as a tribute to his noble, magnificent and versatile poetry.” (D. 1910)

Diego Rivera

On this date in 1886, painter Diego Rivera was born in Guanajuato, Mexico. Rivera attended art school at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City. He then traveled to Europe to study art, later incorporating what he learned about Renaissance frescoes (painting on wet plaster) in his murals. In 1921, he returned to Mexico and became a chronicler of the people via a series of murals. Rivera, along with fellow Mexican painters Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros, led the peoples’ mural movement. Their murals were usually located in public places and reflected social, political and national themes.

His monumental stairway mural in Mexico’s National Palace, Mexico City, is unabashedly critical of religion, particularly the Catholic invaders of Mexico, shown as conquerors conducting autos-da-fé. The mural depicts the mythical and precolonial, pre-Christian history of Mexico and records the Spanish enslavement of native Indians. The final mural, which depicts various injustices toward the people, goes after a triumvirate of “Banker, Army, and Church.” A priest is shown cavorting with a woman en dishabille.

Rivera’s most famous mural is “Man, Controller of the Universe.” He painted it in 1934 as a recreation of his mural “Man at the Crossroads,” which was commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller and then destroyed because Rivera refused to remove a portrait of Lenin from the mural. “Man, Controller of the Universe” represents the world in the 1930s and contains portraits of Lenin and Leon Trotsky. Rivera painted “Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park” between 1947 and 1948. This mural originally included the image of the activist and atheist Ignacio Ramirez holding a sign inscribed “Dios no existe.” Because Rivera refused to remove the inscription, the hotel that held the mural refused to show it. Rivera eventually removed the inscription nine years later and reaffirmed his atheism.

Rivera married several times, most famously to painter Frida Kahlo, 20 years his junior. They were married from 1929-39 before briefly divorcing and remarrying in 1940. She died in 1954. (D. 1957)

“To affirm ‘God does not exist’, I do not have to hide behind Don Ignacio Ramírez; I am an atheist and I consider religions to be a form of collective neurosis.”

— Rivera, “Siqueieros: His Life and Works” by Philip Stein (1994)

Bill Bryson

On this date in 1951, author William McGuire Bryson was born in Des Moines, Iowa, to Bill and Mary (née McGuire) Bryson, who were both journalists. He attended Drake University for two years before dropping out in 1972 and backpacking abroad, which he would write about in Neither Here nor There: Travels in Europe (1992).

While working at a British psychiatric hospital, he met a nurse named Cynthia Billen, whom he married in 1975. After moving back to Des Moines so he could finish his college degree, they returned to England. They have four children: David, Felicity, Catherine and Samuel.

Bryson worked as a journalist for the Bournemouth Evening Echo, the Times of London and The Independent. In 2005 he was appointed Durham University chancellor, succeeding the late Sir Peter Ustinov and serving until 2012. He holds dual U.S. and British citizenship.

Bryson’s freethinking and often humorous A Short History of Practically Everything (2003) explored the sciences, past and present. It won the 2004 Aventis Prize for best general science book and the 2005 EU Descartes Prize for science communication.

In A Walk in the Woods (1997), he told about reading a Tennessee newspaper about how the legislature was in the process of passing a bill forbidding schools from teaching evolution. He recalled the 1925 Scopes “monkey trial” and wrote: “And now the state was about to bring the law back, proving conclusively that the danger for Tennesseans isn’t so much that they may be descended from apes as overtaken by them.”

“I’m not a spiritual person, and the things I’ve done haven’t made me one,” he told The Guardian in March 2005, while allowing that “conventional science and a belief in god are absolutely not incompatible.”

He was elected an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society in 2013, becoming the first non-Briton upon whom the honor was bestowed. His latest book as of this writing, The Body: A Guide for Occupants (2019) aims to foster an understanding of the physical and neurological processes that make up Homo sapiens.

“I don’t know why religious zealots have this compulsion to try to convert everyone who passes before them – I don’t go around trying to make them into St. Louis Cardinals fans, for Christ’s sake – and yet they never fail to try.”

— Bryson, "Neither Here nor There: Travels in Europe" (1991)