sociologists

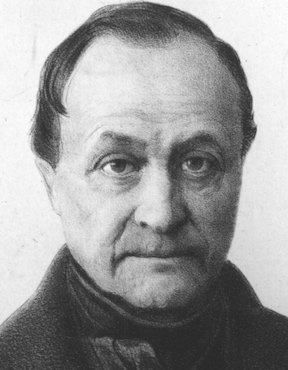

Auguste Comte

On this date in 1798, Auguste Comte, the founder of positivism and generally considered the father of sociology, was born in Montpellier, France. A mathematical prodigy, he rejected belief in God by age 14. He gave a series of lectures on positive philosophy in 1826, which were eventually published. Positivism is defined as a theory stating that certain (“positive”) knowledge is based on natural phenomena and their properties and relations. Thus, information derived from sensory experience, interpreted through reason and logic, is the source of much knowledge.

He married Caroline Massin in 1825. “The Course of Positive Philosophy” (“Cours de Philosophie Positive”) was a series of texts he wrote between 1830 and 1842. The works were translated into English by Harriet Martineau and abridged to form The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte, published in 1853. He was a close friend of John Stuart Mill.

In the 1840s he developed Religion de l’Humanité (Religion of Humanity) for positivists to fulfill the cohesive function once held by traditional worship. His ideas contributed to the rise of ethical culture societies and secular humanism. He died of stomach cancer in Paris at age 59. (D. 1857)

“Daily experience shows that the ordinary morality of religious men is not, at present, in spite of our intellectual anarchy, superior to that of the average of those who have quitted the churches. The chief practical tendency of religious conviction is … to inspire an instinctive and insurmountable hatred against all who have emancipated themselves, without any useful emulation having arisen from the conflict.”

— "The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte" (1853)

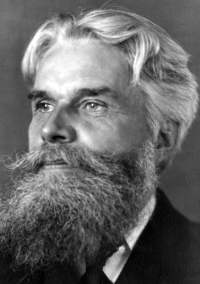

Havelock Ellis

On this date in 1859, sexologist Henry Havelock Ellis was born in Croydon, south London, England. He had four sisters, none of whom married. His father was a sea captain, his mother the daughter of a sea captain. Initially an educator, he returned to school to earn a medical degree but never set up a practice.

He wrote notably on the psychology of sex and criminal reform. His writings include Man and Woman (1894), Sexual Inversion (1897), which advanced the idea that homosexuality is not a disease or a crime, and Affirmations (1898) where his agnostic views are found. He was very conversant with the bible and believed it to be a work of great value.

Ellis studied what today are called transgender phenomena. His landmark six-volume Studies in the Psychology of Sex, was published between 1897-1910. His views were considered so controversial that a bookseller was arrested for selling one of his books.

In November 1891, at the age of 32 and reportedly still a virgin, Ellis married writer and feminist Edith Lees, an open lesbian. Their “open marriage” was the central subject in his autobiography My Life (1939). It’s believed he had an affair with Margaret Sanger.

He died at age 80 in 1939. His wife died of diabetes-related causes in 1916 at age 55. (D. 1939)

“Had there been a Lunatic Asylum in the suburbs of Jerusalem, Jesus Christ would infallibly have been shut up in it at the outset of his public career. That interview with Satan on a pinnacle of the Temple would alone have damned him, and everything that happened after could have confirmed the diagnosis.”

— Ellis, "Impressions and Comments" (1914)

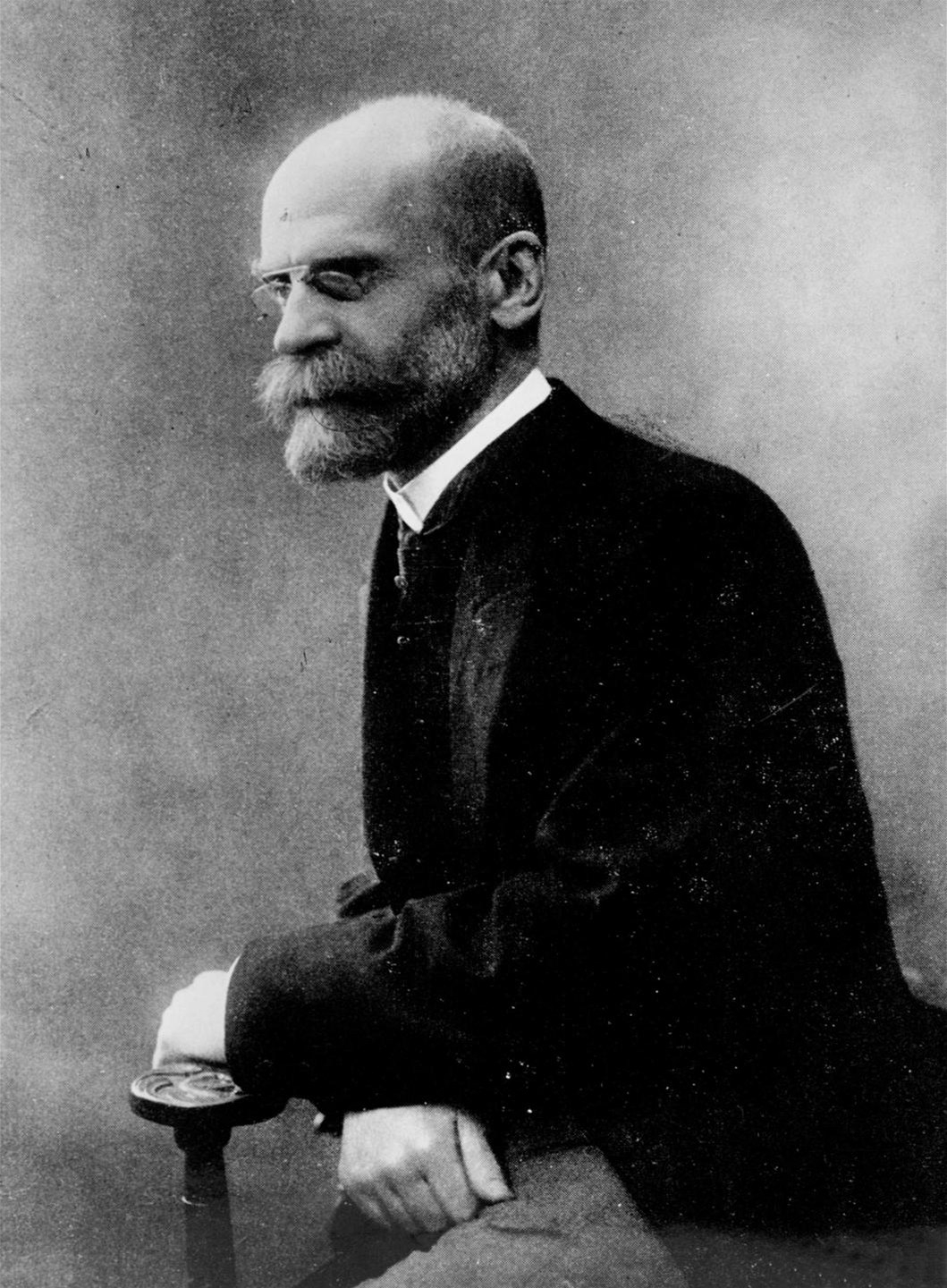

Emile Durkheim

On this date in 1858, David Emile Durkheim, one of the most significant founders of sociology, was born in Epinal in Lorraine, France. His father, grandfather and great-grandfather were prominent rabbis. Durkheim spent time in rabbinical school but broke with Judaism early in life (Emile Durkheim: An Introduction to Four Major Works by Robert Alun Jones, 1986). Durkheim excelled in school, earning his bachelor in letters and sciences in 1875, two years earlier than normal, from College d’Epinal.

He was admitted to the prestigious École Normale Supérieure in 1879 and passed examinations to become a philosophy lecturer in 1882. He was appointed to the Faculty of Letters at Bordeaux to lecture on the “Science Sociale,” marking the first time sociology officially entered the French university system. Durkheim founded the Année Sociologique in 1898, the first French social science journal, still in existence. In 1902 he was appointed chair of education at the Sorbonne in Paris. For a time, his courses were the only lectures required at the Sorbonne.

Durkheim believed religion served a unique role in human life and indeed shaped many social structures, but that its origins were in human society, not from a divine source (“Reasons people choose atheism,” BBC, Oct. 22, 2009). “Frequently described as a ‘secular pope,’ he was viewed by critics as an agent of government anti-clericalism.” (Jones, 1986) Some of his greatest contributions to sociology include The Division of Labour in Society (1893), Rules of the Sociological Method (1895), On the Normality of Crime (1895), Suicide (1897), Sociology and Its Scientific Domain (1900) and The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912). Published posthumously were other important works, including Education and Sociology (1922), Sociology and Philosophy (1924) and Pragmatism and Sociology (1955).

Overwork and the death of a beloved son in World War I in 1916 had severe repercussions on Durkheim’s health. He suffered a stroke and died at the age of 59. He is buried in Paris. (D. 1917)

“Religious force is nothing other than the collective and anonymous force of the clan.”

— Durkheim, "The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life" (1912)

Harriet Martineau

On this date in 1802, Harriet Martineau was born in Norwich, England. The sixth of eight children of a textile manufacturer, she recoiled from her family’s Christian brand of Unitarianism, such as chapel admonitions for children and servants to obey their masters. She went through a devout teenage phase, but as an adult she wrote of Unitarianism: “I disclaim their theology in toto.” Martineau began losing her senses of taste and smell at a young age, becoming increasingly deaf. She turned to writing to help out her family and by 1830 had gained some renown. She blazed a path for women by supporting herself with her nonfiction, writing 50 books and more than 1,600 articles, signed in her own name.

In her memoirs, she boasted of being “probably the happiest single woman in England.” (She never married.) Her two-volume Society in America, as acclaimed as de Tocqueville’s look at life in America, was a definitive work on the status of American women, whom she found unhealthily obsessed with religion. Because of her scrupulous methods of observation, she is credited by some with being the “first sociologist.” Still anthologized is her essay “The Hour and the Man,” a tribute to Haitian slave liberator Toussaint L’Ouverture. After visiting the Mideast with friends, Martineau wrote an examination of the genealogy of Egyptian, Hebrew, Christian and Islamic faiths, Eastern Life: Past and Present (1848). Critics pounced on the “mocking spirit of infidelity.”

Her 1851 book, On the Laws of Man’s Nature and Development, featuring published letters between herself and H.G. Atkinson, made clear her freethought views (see quote below). Wanting to offer children an alternative to “pernicious superstition,” she wrote Household Education (1848) as a secular guide to parents. She translated and condensed the six volumes of French atheist and philosopher Auguste Comte into two volumes, with his approval, in 1853. An erroneous prognosis by a doctor telling her she had fatal heart disease in 1855 propelled her to write her autobiography. She recorded that believers, hearing of her (misdiagnosed) illness, swamped her with self-righteous religious propaganda, such as the New Testament (“as if I had never seen one before”).

When Martineau died in 1876 at age 74, Florence Nightingale wrote that she “was born to be a destroyer of slavery, in whatever form, in whatever place, all over the world, wherever she saw or thought she saw it.”

PHOTO: Martineau, c. 1834, cropped from an oil painting by Richard Evans.

“There is no theory of a God, of an author of Nature, of an origin of the Universe, which is not utterly repugnant to my faculties.”

— Harriet Martineau, "On the Laws of Man's Nature and Development" (1851)

C. Wright Mills

On this date in 1916, Charles Wright Mills was born in Waco, Texas. Mills grew up without friends, books or music and, at the behest of his insurance broker father, initially planned for a career in engineering. Enrolled at Texas Agricultural and Mechanical College in the mid-1930s, Mills frequently wrote for the student newspaper, often about his anger at upperclassmen taunting freshman.

When students criticized his writing for lacking “guts,” he wrote in response, “Just who are the men with guts? They are the men who have the ability and the brains to see this institution’s faults … the men who have the imagination and the intelligence to formulate their own codes; the men who have the courage and the stamina to live their own lives in spite of social pressure and isolation.”

These were less the words of an engineer and more the early musings of one of the 20th century’s great sociologists. After one year at Texas A & M, Mills transferred to the University of Texas-Austin, where he excelled in philosophy, sociology, cultural anthropology, economics and social psychology. At UT-Austin, Mills received a bachelor’s in sociology and a master’s in philosophy, while developing interest in the theories and writings of Karl Marx, Thorstein Veblen and John Dewey.

In 1939 he entered the doctoral program in sociology with a research fellowship at the University of Wisconsin. After completing his coursework in 1941, Mills joined the faculty at the University of Maryland, avoiding military service due to high blood pressure.

Mills involved himself in public affairs in Washington, D.C., and began writing for progressive magazines like The New Republic. In 1945 he joined Columbia University’s Bureau of Applied Social Research, where he attempted to combine his progressive political passions with empirical research. Mills wrote some of the most radical books of the 20th century, including New Men of Power (1948), White Collar (1951) and The Power Elite (1956), all published when the FBI and the attorney general were compiling lists of “subversives,” which put Mills in great personal and professional danger. Interested in the Cuban revolution under Fidel Castro, he visited Cuba in 1960.

Mills, who refused to identify with any political party, movement or religion, adamantly criticized what he called “cheerful robots,” or those who happily follow without questioning authority. He said, “If there is one safe prediction about religion in this society, it would seem to be that if tomorrow official spokesmen were to proclaim XYZism, next week 90 percent of religious declaration would be XYZist.” (“A Pagan Sermon to the Christian Clergy,” 1958.)

The Sociological Imagination (1959), Mills’ most lasting legacy, helped found the subfields of public and critical sociology. It called on sociologists to communicate with the general public instead of just one another and to connect people to public issues. At age 45 he suffered a fatal heart attack. (D. 1962)

“[A]re not all the television Christians in reality armchair atheists? In value and in reality they live without the God they profess; despite ten million Bibles sold each year, they are religiously illiterate.”

“According to your belief [Christian clergy], my kind of man — secular, prideful, agnostic and all the rest of it — is among the damned. I’m on my own. You’ve got your God.”

— Mills, "A Pagan Sermon to the Christian Clergy," remarks to the Board of Evangelical and Social Service, United Church of Canada (Feb. 27, 1958)

Patricia Duffy Hutcheon

On this date in 1926, sociologist Patricia Duffy Hutcheon was born in Saskatchewan, Canada. She earned her undergraduate degree in education and history and her Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Queensland, Australia. In early adult life, because of several adverse personal experiences, she became active in promoting women’s rights and equality of the sexes. She married Alexander “Sandy” Hutcheon. She taught sociology at the University of Regina and the University of British Columbia. She was in great demand as a public speaker and became a prominent humanist in the academic world.

Her 1975 textbook, A Sociology of Canadian Education, was the first ever published on that subject and became a classic. She wrote many books, including Leaving the Cave: Evolutionary Naturalism in Social Scientific Thought (1996), Building Character and Culture (1999) and The Road to Reason: Landmarks in the Evolution of Humanist Thought (2001). In later life her studies focused on the trend of tribalism and the dangers it presented for society.

Hutcheon was named Humanist of the Year 2000 by the Canadian Humanist Association and received the Distinguished Humanist Service Award 2001 from the American Humanist Association. She also assisted in drafting the Humanist Manifesto III issued by the AHA in 2003. She was a member of the BC Humanist Association. (D. 2010)

”Only humanism has a planetary perspective already in place. It is up to us to try to persuade the more open-minded members of the world community to join us in rejecting tribalism before it is too late.”

— Hutcheon in her essay, “Can Humanism Stem the Rising Tide of Tribalism?”

Emily Palmer Cape

On this date in 1865, sociologist Emily Cape (née Palmer) was born to wealthy parents in New York City. She was the first woman admitted to Columbia University and also attended Barnard College and the University of Wisconsin. She studied sociology with Lester Frank Ward, who is sometimes called the father of American sociology. Cape became his editing assistant while he worked on his multi-volume Glimpses of the Cosmos (first volume published in 1913). She married Henry Cape in 1890 and had two children.

“Like Professor Ward, she is an Agnostic and an ardent humanitarian,” historian Joseph McCabe wrote in 1920 (A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists). Cape founded a School of Sociology in New York and was a member of the American Sociological Society and the Rationalist and Positivist Societies of London. Her books include Oriental Aphorisms (1906), Fairy Surprises for Little Folks (1908) and Lester F. Ward: A Personal Sketch (1922).

As a 60-year-old, Cape undertook a cruise around the world in 1926-27. In her 278-page journal describing tours in Japan, Thailand, India and Egypt, she commented upon some “ignorant” priests on board: “No wonder their ‘flocks’ are ‘low in education.’ ” She died at age 88 at home in Sarasota, Fla. (D. 1953)

“Cape was not your average socialite; she was an agnostic, a freethinker, and a self-described ‘suffragist.’ ”

— South Orange, N.J. Patch (Nov. 27, 2009)