prime-ministers

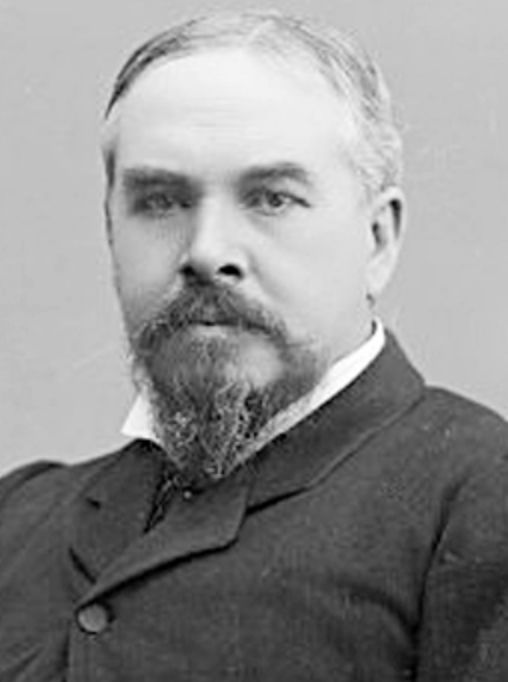

John Ballance

On this date in 1839, John Ballance was born in County Antrim, Northern Ireland, the first of 11 children. The ironmonger’s apprentice emigrated first to Birmingham, then, with his new wife, to New Zealand.

First elected to the House of Representatives in 1875 on a ticket calling for free education, Ballance later became Minister of Education and Minister of Finance. He was then appointed Native Minister and Minister for Defence and Lands. Ballance founded his country’s Liberal Party. In 1891, Ballance was elected the 14th Prime Minister of New Zealand as a Liberal.

“He took his politics from his liberal mother, who had a Quaker upbringing, rather than his conservative Church of Ireland father. Ultimately, Ballance rejected Christianity altogether, becoming a free thinker.” (Ulster historian Gordon Lucy, Belfast News Letter, July 23, 2018)

Ballance co-founded the Wanganui Freethought Association in 1883 and published The Freethought Review from 1883 to 1885.

He is credited with many progressive reforms, improving government relations with Maoris, and calling for the “absolute equality of the sexes.” As premier, Ballance secured the right to vote for his countrywomen, making New Zealand the first country to do so. He died at age 54 at the height of his popularity after surgery to treat an intestinal disease. (D. 1893)

“A man is not good for much unless there be something of the heretic in him; unless he has a mind so independent, honest, and courageous as to think for himself, and also to choose his own opinions.”

— The Freethought Review (Oct. 1, 1883)

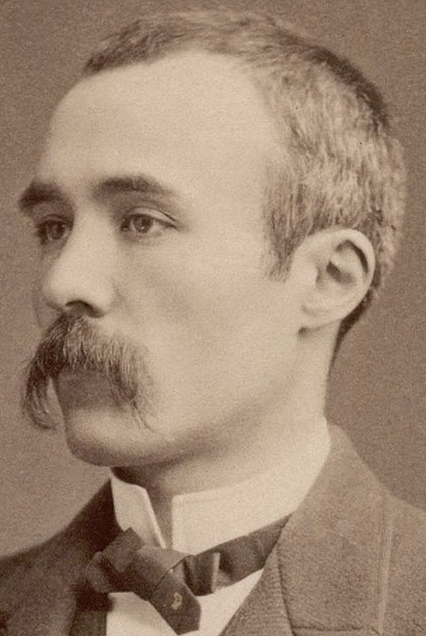

Georges Clemenceau

On this date in 1841, French statesman and journalist Georges Clemenceau was born in France. Clemenceau followed in his father’s footsteps by becoming a physician and a freethinker. At 16 he was briefly suspended from school for debating Christianity with a teacher. Clemenceau began writing for Emile Zola‘s newspaper Travail, advocating a republic and free speech, and served 63 days in jail in 1862 as a student demonstrator under the reign of Napoleon III.

As a foreign correspondent for Le Temps, he went to New York City in 1865. He met his wife-to-be teaching French at a ladies seminary in Connecticut. Clemenceau’s book The Great God Pan (1869) described how superstitions live on under new guises. He also translated John Stuart Mill’s book Auguste Comte and Positivism. Returning to France, he became mayor of Montmartre, served as a member of the Paris Municipal Council (1871-76) and was elected five times to the National Assembly.

During an interlude when he left politics, Clemenceau returned to journalism. His newspaper articles, permeated with anti-clericalism and the promotion of rationalism, eventually were bound into 19 volumes. He contributed to L’Aurore newspaper and worked tirelessly for the release of Alfred Dreyfuss, writing more than a thousand influential articles about the case.

Known as “The Tiger,” the politician returned to the Assembly in 1902, became interior minister, then prime minister (1906-09). Clemenceau was again elected prime minister in 1917 and was toasted as “Pere Victoire” (Father Victory) at the close of World War I. Clemenceau was a connoisseur of the arts and a personal friend of Rodin. He was buried, per instructions, with no rites. D. 1929.

"Not only have the ‘followers of Christ’ made it their rule to hack to bits all those who do not accept their beliefs, they have also ferociously massacred each other, in the name of their common ‘religion of love,’ under banners proclaiming their faith in Him who had expressly commanded them to love one another."— Clemenceau memoir, "In the Evening of My Thought" (Au Soir de la pensee), 1929

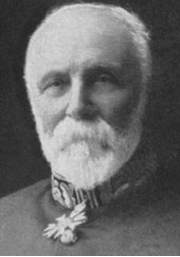

Robert Stout

On this date in 1844, New Zealand statesman Robert Stout was born in the Shetland Isles, Scotland. He was educated in parish schools, qualified as a student teacher at age 13, then as a surveyor in 1860. Stout emigrated to New Zealand in 1863. After teaching in Dunedin, he studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1871. He served as a member of the Provincial Council of Otago in 1872 and was first elected to the House of Representatives in 1875 as a Liberal. He served as attorney general and minister for lands and immigration in 1878-79.

He became president of the Dunedin Freethought Association in 1880 and defended the Auckland Rationalist Association when it was threatened with prosecution for selling its magazine on Sundays. Stout eventually introduced a bill, which passed, reducing Blue Law fines and restrictions. He was often described as New Zealand’s version of Charles Bradlaugh and America’s Robert Ingersoll. He was returned to Parliament in 1884 and served as premier, attorney general and minister of education from 1884-87. He was knighted in 1886.

Stout promoted secular secondary schools and medical and welfare services and was sympathetic to the Maori and land reform. The Married Women’s Property Act became law while he was prime minister. Stout returned to Parliament in time to finally see passage of women’s suffrage in 1893, a reform he had promoted. He was appointed chief justice, serving from 1899-1926. He was also chancellor of New Zealand University (1903-23).

Stout was appointed after retiring as chief justice to the Legislative Council, where he immediately defended secular education, which was under attack by religionists seeking to introduce bible reading and prayers in school: “I fear that Parliament may set up a little state church to make people morally good. … it will make them immoral, for it will inaugurate bitterness and ill feeling.” He married Anna Paterson Logan, the daughter of social reformers and freethinkers, and they had six children. D. 1930.

"We recognise no authority competent to dictate to us. Each must believe what he considers to be true and act up to his belief, granting the same right to everyone else."

— Stout, inaugural address as Dunedin Freethought Association president, 1880

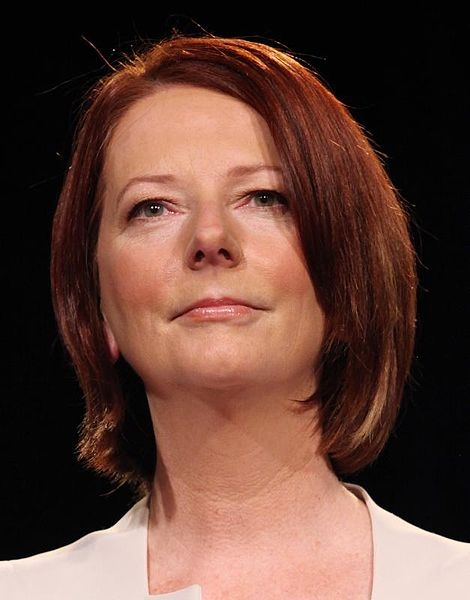

Julia Gillard

On this date in 1961, Australia’s first female prime minister, Julia Eileen Gillard, was born in Wales into a Baptist family that migrated to Australia in 1965. Initially she wanted to be a teacher but a friend’s mother suggested a career in law since she already had excellent debating skills. Gillard studied art and law at the University of Adelaide, where she became active in politics. She transferred to the University of Melbourne and became president of the Australian Union of Students in 1983. She graduated from the University of Melbourne with a degree in law in 1986, worked for a law firm and became its first female partner in 1990.

Specializing in industrial law, Gillard fought to improve working conditions for women in clothing and textile industry sweatshops. In 1996 she was appointed chief of staff for Victorian opposition leader John Brumby and was elected to the federal Parliament in 1998. Gillard was sworn in as Australia’s first female deputy prime minister in 2007, simultaneously heading three cabinet agencies. She ousted Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in 2010.

She told ABC Radio Melbourne in 2010, “I grew up in the Christian church, a Christian background. I won prizes for catechism, for being able to remember Bible verses. I am steeped in that tradition, but I’ve made decisions in my adult life about my own views” and “I’m not going to pretend a faith I don’t feel.” (Telegraph UK, “Australian prime minister ‘does not believe in God.’ ”) She added, “For people of faith, I think the greatest compliment I could pay them is to respect their genuinely held beliefs and not to engage in some pretence about mine.”

PHOTO: MystifyMe Concert Photography (Troy) under CC 2.0

ABC RADIO HOST: Do you believe in God?

GILLARD: No, I don’t, Jon, I’m not a religious person. I’m of course a great respecter of religious beliefs but they’re not my beliefs.— "Julia Gillard risks Christian vote with doubts on God," The Australian (June 30, 2010)

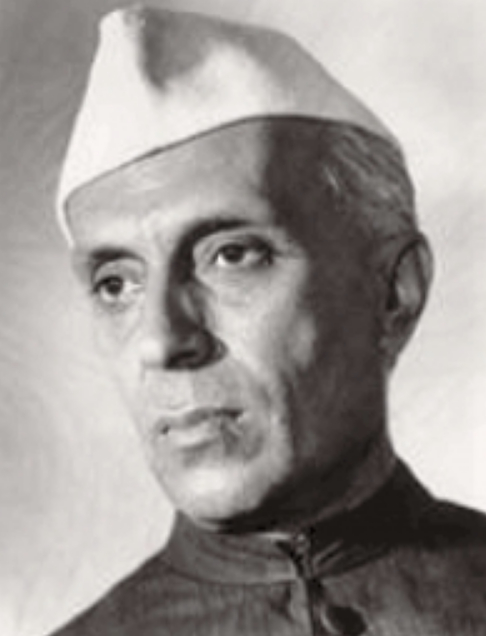

Jawaharlal Nehru

On this date in 1889, India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru was born in Allahabad to a humanist father and Hindu mother. Nehru was educated in England and at Cambridge University and practiced law. He became an early protégé of Gandhi in the 1920s and spent much of 1930 to 1936 in jail for civil disobedience campaigns. He was imprisoned for 32 months during the Quit India campaign, during which he and Gandhi pledged support for Great Britain during World War II only if India were freed. Upon the liberation and creation of India (Aug. 15, 1947), Nehru became the nation’s first prime minister and led the nation through its turbulent beginnings for 18 years.

Nehru, a rationalist and agnostic, believed in industrialization, education and mildly socialistic policies. Under his tutelage, India adopted a constitution which decreed separation of church and state. During the Cold War he appealed to the U.S. and the USSR to start nuclear disarmament. Nehru authored several books, including his autobiography.

Nehru married Kamala Kaul in 1916. Their only daughter Indira was born in 1917. Kamala gave birth in 1924 to a boy who only lived a week. She died in 1936. Indira Gandhi became prime minister in 1966. Nehru died of a heart attack at age 74 in New Delhi. (D. 1964)

“Essentially, I am interested in this world, in this life, not in some other world or a future life. Whether there is such a thing as a soul, or whether there is a survival after death or not, I do not know; and, important as these questions are, they do not trouble me in the least.”

— Nehru, "The Discovery of India," 1946 (written while imprisoned by the British)

Indira Gandhi

On this date in 1917, Indira Gandhi (née Nehru) was born in Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh, India, to a wealthy, upper-caste Brahmin Hindu family. Her father, Jawaharlal Nehru, was India’s first prime minister and popular independence leader. Before completion of her education at Oxford University, Gandhi joined the Indian independence movement, which led to her imprisonment for 13 months on charges of subversion by British colonial authorities.

In 1942 she married a Congress Party militant, Feroze Gandhi, but her marriage suffered as her father took office as prime minister in 1947 and invited her to be his official hostess. In this position she studied the world’s most powerful political elites and in the 1950s began building her own political career. She was elected Congress Party president in 1959 and helped oust the communist government from the southern state of Kerala. She served in the upper house of parliament in 1964 and in 1967 became the first woman leader of a major country in modern times.

As prime minister she strengthened the authority of the federal government and strongly objected to religious sectarianism that, she believed, threatened Indian democracy. While some of her domestic policies were viewed as weak, she managed to keep relative social peace and silence radical opposition movements. She achieved great success in her foreign policy and, after winning reelection in 1971, led India to victory in a bitter war with Pakistan (that also resulted in the birth of Bangladesh).

While her popularity grew among Indians and especially the poor, Gandhi gained a reputation as an authoritarian within her own party. After an Indian court determined her 1971 election was illegitimate, Gandhi declared a state of emergency, suspending civil liberties and jailing thousands of her critics. Facing internal and international pressure, she returned to democratic government in 1977 but the people elected a former rival, Morarji Desai, to replace her.

Desai attempted to destroy Gandhi’s reputation but she fought back by campaigning in rural villages and was elected as prime minister for the fourth time in 1980. Sikh terrorist factions in the Punjab state demanded an independent state, but Gandhi refused to negotiate and in June 1984 ordered an army assault on a militant Sikh temple, which resulted in the loss of over 1,000 lives. Over the next months, Gandhi remained undeterred by numerous death threats from Sikh militants. She told Newsweek, “In politics you simply can’t hide from people. My life has been one with India, and it makes no difference to me if I die standing or in bed.”

Gandhi was gunned down in 1984 in her garden in New Delhi by her Sikh bodyguards. Following her death was a period of extreme tension and bloodshed between Hindus and Sikhs across India. (D. 1984)

"There exists no politician in India daring enough to attempt to explain to the masses that cows can be eaten."

— Gandhi, quoted by Oriana Fallaci in "Indira's Coup," New York Review of Books, 1975

Pedro Pablo Abarca Aranda

On this date in 1719, Spanish statesman Pedro Pablo Abarca de Bolea y Jiménez de Urrea, later the 10th count of Aranda, was born in northern Aragon. He started ecclesiastical studies in the seminary of Bologna, but at age 18 changed to the Military School of Parma. In 1740 he was severely wounded in combat in the War of the Austrian Succession. He then lived in Paris, where he met Diderot and Voltaire and studied the Encyclopédie and Enlightenment movements.

After an ambassadorship to Poland, Aranda became governor of Valencia in 1764. When Charles III was driven from the capital in a 1766 riot, he summoned Aranda to Madrid and made him president of the Council of Castile. Until 1773 he was the most important government minister in Spain. He restored order and aided the king in his work of administrative reform.

Perhaps his greatest achievement, which endeared him throughout Europe to the philosophical and anti-clerical parties, was his work on behalf of the suppression and expulsion of the Jesuits, whom the king considered responsible for the 1766 riot.

Aranda was well-known to American revolutionaries as a supporter. His open sympathy with the French Revolution in 1789 brought him into collision with reactionary forces in Spain and he was imprisoned for a short time at Granada and threatened with a trial by the Inquisition. The proceedings did not go beyond the preliminary stage and he died at age 80. (D. 1798)