May 31

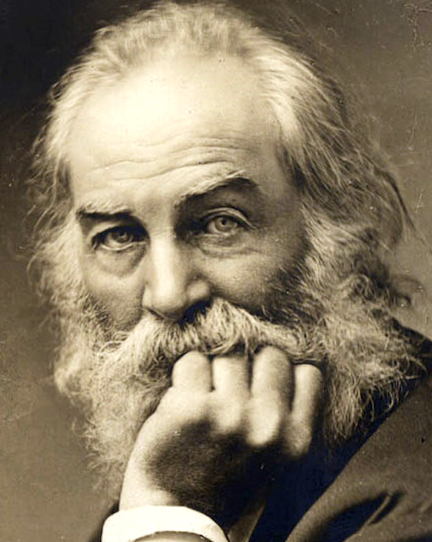

Walt Whitman

On this date in 1819, Walter Whitman was born on Long Island, N.Y., the second of nine children born to Louisa (Van Velsor) and Walter Whitman, who had Quaker ties. After working as a clerk, teacher, journalist and laborer, Whitman wrote his masterpiece, Leaves of Grass, pioneering free-verse poetry in a humanistic celebration of humanity, in 1855. Emerson, whom Whitman revered, said of Leaves of Grass that it held “incomparable things incomparably said.”

During the Civil War, Whitman worked as an army nurse, later writing Drum Taps (1865) and Memoranda During the War (1867). His health was compromised by the experience and he was given work at the Treasury Department in Washington. After a stroke in 1873, which left him partially paralyzed, Whitman lived with his brother, writing mainly prose, such as Democratic Vistas (1870).

Leaves of Grass was published in nine editions, with Whitman elaborating on it in each successive edition. In the preface of the 1855 edition, Whitman wrote, “This is what you shall do: Love the earth and sun and animals, despise riches, give alms to everyone that asks, stand up for the stupid and crazy, devote your income and labor to others, hate tyrants, argue not concerning God.” In 1881, the book had the compliment of being banned by the commonwealth of Massachusetts on charges of immorality.

Whitman was influenced by deism and was a religious skeptic. Invited in 1874 to write a poem about the Spiritualism movement, he responded, “It seems to me nearly altogether a poor, cheap, crude humbug.” (“Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself” by Jerome Loving, 1999) Biographers continue to debate Whitman’s sexuality, and he is usually described as either homosexual or bisexual in his feelings and attractions.

He died at 72 of pleurisy and tuberculosis in Camden, N.J. Robert Ingersoll delivered the public eulogy at the cemetery. (D. 1892)

“I think I could turn and live with animals, they’re so placid and self-contain’d,

I stand and look at them long and long.

They do not sweat and whine about their condition,

They do not lie awake in the dark and weep for their sins,

They do not make me sick discussing their duty to God.”— Whitman, "Leaves of Grass" (1891 edition)

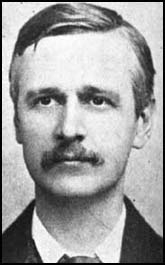

Graham Wallas

On this date in 1858, political scientist, public official and educator Graham Wallas, the son of a puritanical clergyman, was born in Sunderland, England. He studied at Corpus Christi College at Oxford where he abandoned religion in favor of rationalism. To avoid participating in communion, he resigned in 1885 from his teaching post at Highgate School in London, where he was president of the Rationalist Press Association. In 1886, Wallas joined the Fabian Society, and befriended George Bernard Shaw, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, and co-founded the London School of Economics with them.

He was an outspoken critic of the misuse of Darwin’s work by proponents of the then-popular “social Darwinism.” He also believed very strongly in representative government and, in the face of great opposition, said the solution was not to do away with representative government but to increase participation by citizens. Wallas resigned from the Fabians in 1904 over political disagreements.

He joined the faculty of the London School of Economics in 1895 and taught there until his retirement in 1923. He served on the London County Council from 1904 to 1907, chaired the school of management committee of the London School Board and in 1914 became a professor of political science at the University of London.

Among Wallas’s many publications are Property Under Socialism (1889), Human Nature in Politics (1908) — a pioneering work on applying psychology to political analysis — The Great Society (1914) and The Art of Thought (1926). Wallas wrote in Human Nature in Politics: “Plato … proposed that the loyalty of the subject-classes in his Republic should be secured once for all by religious faith. His rulers were to establish and teach a religion in which they need not believe. They were to tell their people ‘one magnificent lie’; a remedy which in its ultimate effect on the character of their rule might have been worse than the disease which it was intended to cure.” (D. 1932)

“People in a state of strong religious emotion sometimes become conscious of a throbbing sound in their ears, due to the increased force of their circulation. An organist, by opening the thirty-two-foot pipe, can create the same sensation, and can thereby induce in the congregation a vague and half-conscious belief that they are experiencing religious emotion.”

— Wallas, "Human Nature in Politics, Non-Rational Inference in Politics" (1908)