June 28

Richard Rodgers

On this date in 1902, songwriter Richard Rodgers, one of the great composers of musical theater, was born on Long Island, N.Y., to a prosperous Jewish family (with an atheist grandmother). While attending Columbia University, he met his first major writing partner, lyricist Lorenz Hart, then studied serious music at the Institute of Musical Art, known today as Juliiard. After the success of “The Garrick Gaieties“ revues (1925-30), Rodgers and Hart became a huge Broadway songwriting force. During the 1920s and 1930s they produced the musicals “Babes in Arms,” “Pal Joey” and “The Boys From Syracuse.”

After Hart’s early death, Rodgers teamed up with Oscar Hammerstein II to produce “Oklahoma!” (1943) and 10 more musicals, including “Flower Drum Song,” “Carousel,” “South Pacific,” “The King and I” and “The Sound of Music” plus the movie “State Fair.” He wrote 39 Broadway musicals and vastly improved the musical theater by seamlessly weaving music, words and dance. The Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals earned a total of 34 Tony Awards, 15 Academy Awards, two Pulitzer Prizes, two Grammy Awards and two Emmy Awards. After Hammerstein’s death, Rodgers collaborated with Stephen Sondheim, Sheldon Harnick and Martin Charnin.

Rodgers wrote many of the standards in the Great American Songbook: “Blue Moon,” “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered,” “Do-Re-Mi,” “Getting to Know You,” “Have You Met Miss Jones?” “If I Loved You,” “Isn’t it Romantic?” “It Might as Well be Spring,” “Manhattan” “My Favorite Things,” “My Funny Valentine,” “My Heart Stood Still,” “Some Enchanted Evening,” “Spring is Here,” “This Can’t Be Love,” “This Nearly Was Mine,” “With a Song in my Heart,” “You Took Advantage of Me” and many more. Rodgers’ wife, Dorothy, said: “We are not religious. We are social Jews.”

He died at age 77 after surviving cancer of the jaw, a heart attack and a laryngectomy. His ashes were scattered at sea. (D. 1979)

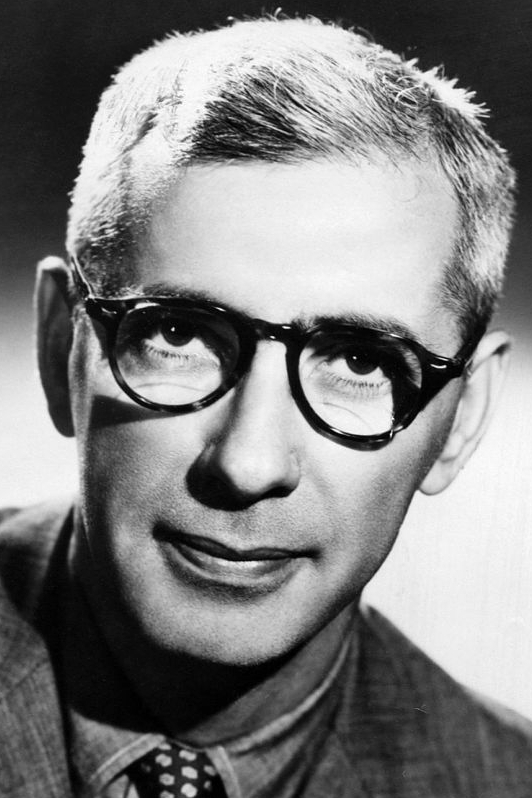

PHOTO: Rodgers watching auditions in 1948 at the St. James Theatre.

“Those around him knew … Rodgers was an atheist. At the age of twelve, Mary Rodgers Guettel [his daughter] asked her father whether he believed in God and he answered that he believed in people. 'If somebody is really sick, I don’t pray to God, I look for the best doctor in town.'”

— Biographer Meryle Secrest, "Somewhere For Me: A Biography of Richard Rodgers" (2001)

Ashley Montagu

On this date in 1905, Ashley Montagu (born Israel Ehrenberg) was born in East London. He adopted his new last name in homage of Lady Mary Montagu, a freethinking feminist from the 18th century. Montagu graduated from the University College- London and received a Ph.D. in anthropology from Columbia University in 1937. He broke ground as an anthropologist in writing about race. His book Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race (1942) was his most influential work on that score.

Some of his 60 other books included Coming Into Being of the Australian Aborigines (1937), Race and Kindred Delusions (1939) and The Natural Superiority of Women (1953). Montagu applied his work as a social biologist in writing on diverse topics, including gun control, peace, evolution, marriage, children, emotions and even a biography, The Elephant Man, about the Victorian John Merrick, which was made into a movie in 1980. His numerous articles, popular and scientific, included “Nothing Can Be Said in Favor of Smoking” (1942). The American Humanist Association named the humanitarian “Humanist of the Year” in 1995.

A statement often attributed to him (primary source unknown): “The Good Book — one of the most remarkable euphemisms ever coined.” (D. 1999)

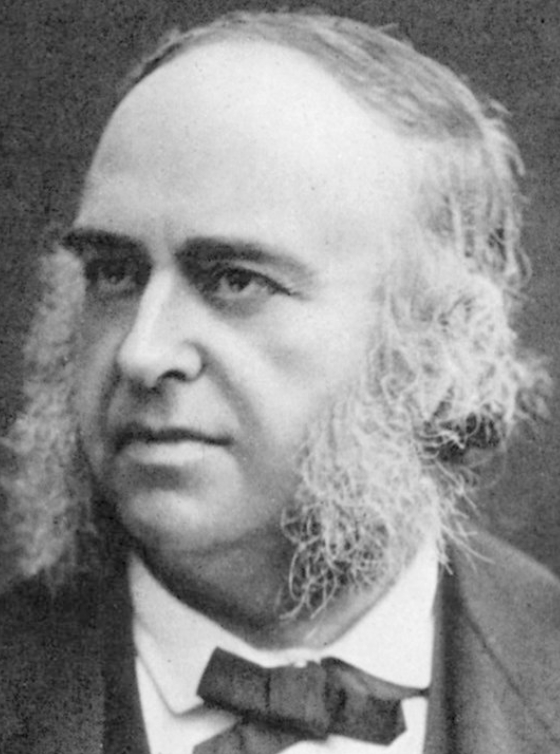

PHOTO: Montagu at age 53 in 1958.

“The scientist believes in proof without certainty, the bigot in certainty without proof. Let us never forget that tyranny most often springs from a fanatical faith in the absoluteness of one's beliefs.”

— Montagu, "Science and Creationism" (1984)

Paul Broca

On this date in 1824, Pierre Paul Broca was born in Sainte-Foy-la-Grande, France. He began attending medical school when he was only 17, graduated at 20 and later earned degrees in mathematics, literature and physics. Broca went on to become a professor of surgical pathology at the University of Paris and was an accomplished anatomist who advanced understanding of speech production in the brain. His most important achievement was discovering Broca’s area, a region of the brain responsible for speech production.

His work was also influential in cancer pathology and treatment of brain aneurysms. Broca founded the Anthropological Society of Paris in 1859, and his findings in anthropology often contradicted biblical teachings. Broca himself died, ironically, of a brain aneurysm. His brain was preserved after his death, becoming the inspiration for Carl Sagan’s 1974 book Broca’s Brain.

According to The End of the Soul by Jennifer Michael Hecht (2003), Broca thought that the more educated humans were, the less religious they would become. Broca also firmly supported natural selection: “Far from blushing in shame for my species because of its genealogy and parentage, I will be proud of all that evolution has accomplished.” (D. 1880)

"[Religion is] nothing more than a type of submission to authority."

— Broca, "Bulletins de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris"

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

On this date in 1712, Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born in Geneva, Switzerland, of French Huguenot parents. His mother died giving birth to him. As a young lad he was apprenticed to an engraver but ran away at age 16 and went into domestic service. His Catholic employer, Mme. De Warens, took him as her lover and allowed him to study literature and philosophy.

In 1741 he moved to Paris and met freethinkers Diderot and D’Holbach, and was asked to write about music for the Dictionnaire Encyclopedique. Rousseau is known for promulgating the idea of the “noble savage” living in a “state of nature,” but intellectual historian Arthur Lovejoy wrote that that misrepresents Rosseau’s thinking.

While living with wealthy patrons, Rousseau worked for eight years writing the novel Julie, ou la nouvelle New Heloise (1760), The Social Contract (1762) and Emile (1762), a treatise on education. The Social Contract introduced the motto “Liberte, egalite, fraternite.” As a Deist with kind words for the gospels, Rousseau was less radical about religion than his friends, perhaps more interested in pursuing his romantic vision of human nature: “Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains.” He believed in a “religion of man.”

Despite Emile’s sympathetic words for the rights of children, Rousseau gave the five illegitimate children he fathered with a hotel maid to foundling homes. His Letters Written to Montaigne (1762) promoted freedom from the church. His arrest was ordered in Paris after publication of Emile and he fled to Switzerland, where officials, in addition to condemning Emile, also condemned The Social Contract and expelled him. Rousseau took refuge in Neuchatel under the King of Prussia but was eventually driven out for his “irreligion.”

He wrote Confessions in England and resettled in Paris in 1770. Freethought biographer Joseph McCabe wrote, “His character was far inferior to that of the ‘irreligious’ Deists of Paris. He was, in fact, the most religious and least virtuous of ‘the philosophers’; far inferior in nobility of character to the Agnostics Diderot and D’Alembert, and more faulty than Voltaire. We must, however, not forget his unhappy circumstances and temperament. He rendered monumental service to his fellows.” (A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists.) (D. 1778)

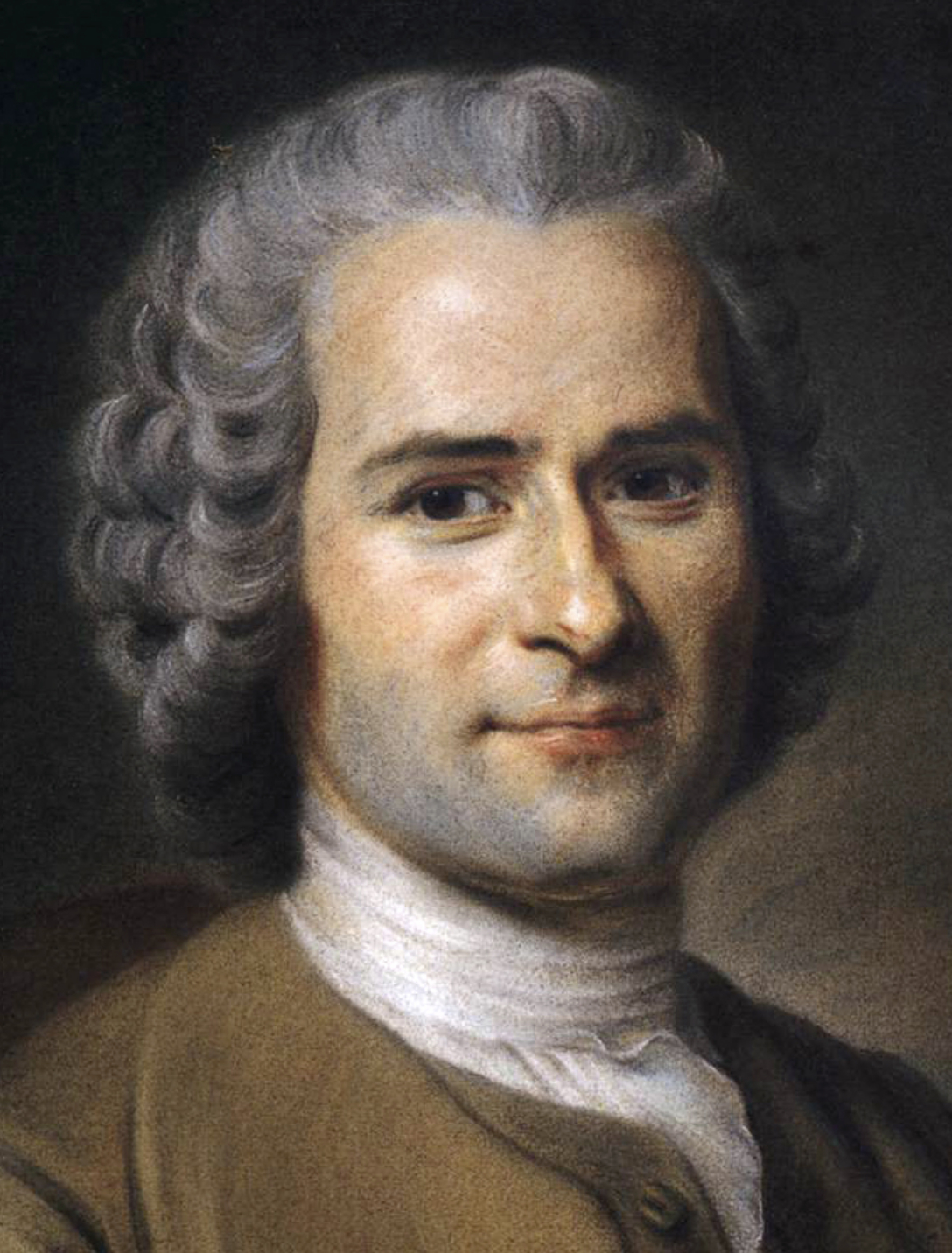

PHOTO: Portrait of Rosseau by Maurice Quentin de La Tour, 1753.

“Whoever dares to say: ‘Outside the Church is no salvation,’ ought to be driven from the State.

But I am mistaken in speaking of a Christian republic; the terms are mutually exclusive. Christianity preaches only servitude and dependence. Its spirit is so favorable to tyranny that it always profits by such a regime. True Christians are made to be slaves, and they know it and do not much mind: this short life counts for too little in their eyes.”

— Rousseau, "The Social Contract" (1762)

Lalla Ward

On this date in 1951, Sarah “Lalla” Ward was born in London to Edward Ward, 7th Viscount Bangor, and his fourth wife, Marjorie Alice Banks. The name Lalla comes from her attempts as a toddler to pronounce her first name. She studied drama at the University of London’s Central School of Speech and Drama, where she graduated in 1971.

She has had a successful acting career, which included playing Ophelia in the 1980 movie “Hamlet, Prince of Denmark.” She also starred as the doctor’s companion, Romana, in the popular TV show and longest running sci-fi series “Doctor Who” from 1979-81.

Ward was married to atheism advocate and evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins. They wed in 1992 after being introduced by mutual friend Douglas Adams, the author of “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.” They jointly announced an “entirely amicable” separation in 2016. Ward has written three books, two on knitting and one on embroidery, and her artwork has also been featured in calendars. She also illustrated many of Dawkins’ books.

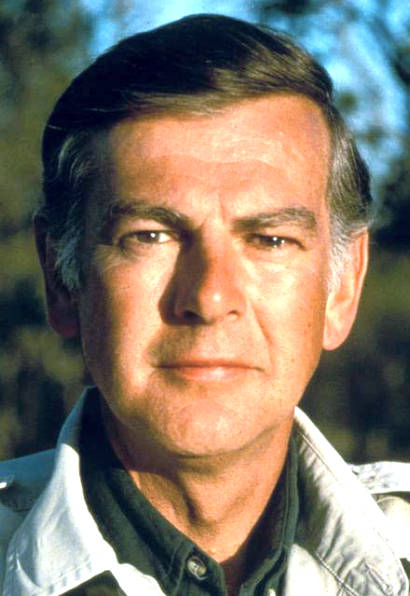

PHOTO: A young Lalla Ward, date unknown.

"We are both strongly non-religious, and we have similar views on what’s important in life."

— Richard Dawkins in "How We Met: Richard Dawkins and Lalla Ward" (The Independent, June 19, 1994)

Donald C. Johanson

On this date in 1943, paleoanthropologist Donald Carl Johanson was born in Chicago to Swedish immigrants. His father, a barber, died when he was 2 and his nonreligious mother, who came to the U.S. at age 16, worked as a cleaning lady to support them.

Johanson recalled some friends convincing him when he was about 12 to attend Sunday services at a Swedish Lutheran church. When he got home, his mother asked, in her heavily accented English, “Deed they ask you fer money?” When he said they did, she replied, “The first thing they’ll do is control you, then they will instill fear in you, and then they will take your money.” (FFRF convention speech, Oct. 24, 2014)

He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Illinois-Urbana in 1966 and his master’s degree (1970) and Ph.D. (1974) from the University of Chicago. The title of his Ph.D. dissertation was “An Odontological Study of the Chimpanzee with Some Implications for Hominoid Evolution.”

He started doing archaeological field work as an undergraduate. His first trip to Africa was in 1970, and he was working as an associate professor of anthropology at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland in November 1974 when the discovery he is best known for was made. Working with Frenchmen Yves Coppens and Maurice Taieb at the Hadar paleontological site in northeastern Ethiopia, Johnson unearthed the fossil of a young adult hominid australopithecine that became known as “Lucy” (named after, over Johanson’s objection, the Beatles’ song “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds,” which happened to be playing that evening at base camp).

Lucy, the first discovered member of Australopithecus afarensis, believed to be a distant ancestor of modern humans, was dated to 3.2 million years ago. Johanson later called her “the poster child for paleoanthropology and human origins.” The full excavation took three weeks and revealed 47 of Lucy’s 207 bones. The implications of the discovery were such that in 1979, Time magazine declared her a “front-page celebrity.” The bones are housed in a specially constructed safe in the paleoanthropology laboratories of the National Museum of Ethiopia in Addis Ababa.

In 1981, Johanson established the Institute of Human Origins in Berkeley, Calif., moving it to Arizona State University in Tempe in 1997. He served as its director until 2008 and as a professor in the university’s School of Human Evolution and Social Change. He continues to conduct lab research, write prolifically and lecture internationally as of this writing in 2020. His Lucy: The Beginnings of Humankind (with Maitland Edey) won a National Book Award in Science in 1982. More recently, with Kate Wong, he published Lucy’s Legacy: The Quest for Human Origins (2009).

His honors include the Academy of Humanism’s 1983 humanist laureate, the 1991 In Praise of Reason Award from the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, FFRF’s 2014 Emperor Has No Clothes Award, numerous honorary degrees and membership since 2013 on the Advisory Council of the National Center for Science Education. He was elected in 2020 to the Board of Scientific Advisors of JASON, named for Jason, leader of the mythological Greek Argonauts. The board was established in 1960 to advise the U.S. government on matters of science and technology.

Johanson’s personal life, including any significant relationships, is not well-documented. In 1976 the Cleveland Plain Dealer noted that he drove a sports car and dated actress Morgan Fairchild: “The very appealing Johanson is one of the most handsome and brilliant bachelors in the country.”

His exceptionally informative speech to FFRF convention-goers in Los Angeles in 2014 to accept the Emperor Award can be read here. In it he said, “We know, every single one of us in this room, who the creator was — Mother Nature.”

“I’ve always been an atheist. I didn’t have to be converted to atheism.”

“The anti-science aspect of religion is what bothers me most intensely. It’s personified in this cartoon: “Welcome to church, you won’t be needing that [image of human brain] in here.”— Remarks to FFRF national convention (Oct. 24, 2014)

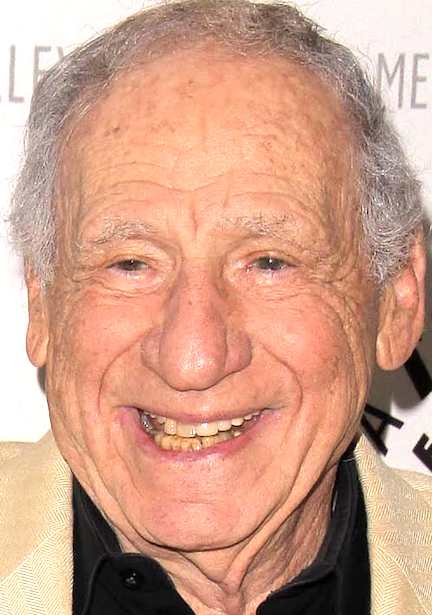

Mel Brooks

On this date in 1926, comedic genius Mel Brooks (né Melvin James Kaminsky) was born in Brooklyn, N.Y., to Kate (Brookman) and Max Kaminsky, whose Jewish lineage stemmed from Poland and Ukraine. His father died of kidney disease at age 34 when Brooks was 2, and he grew up in tenement housing.

He was drafted in 1944 into the U.S. Army after enrolling at Brooklyn College for a year. He served as a combat engineer defusing land mines in France and Germany, was promoted to corporal and participated in the Battle of the Bulge.

Unenthused about a clerk’s job his mother had lined up for him at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, he started working in Borscht Belt resorts and nightclubs in the Catskills as a drummer, pianist and stand-up comic. His friend Sid Caesar hired him as a TV comedy writer, and in 1950 he worked on Caesar’s variety series “Your Show of Shows” with Carl Reiner, Neil Simon and others.

After he moved to Hollywood in 1960, he and Reiner created the “2000 Year Old Man” character, which went on to be featured on five successful comedy albums and numerous TV sketches. Brooks played a man claiming he’d witnessed Jesus Christ’s crucifixion, had 42,000 children “and not one comes to visit me.”

With Buck Henry he created the TV spy spoof “Get Smart” that aired from 1965-70. His first feature film, “The Producers” (1967), won the Best Original Screenplay Oscar and was a Broadway smash. That Brooks could make “Springtime for Hitler” palatable in the mainstream and arguably hilarious, says a lot about his talents.

“People like rabbis would write to me and say, ‘This is execrable.’ And I’d say, ‘You can’t bring folks like Hitler down by getting on a soapbox – they’re better at it than we are. But if you can humiliate them, ridicule them, and have people laugh at them – you’ve won.’ I knew ‘Springtime for Hitler’ was perfect, I knew it was right.” (Men’s Journal, June 2013)

He went on in the last third of the 20th century to join the elite as an actor, director and producer on screen and stage. “Blazing Saddles” and “Young Frankenstein” in 1974 were followed by “Silent Movie,” “High Anxiety,” “History of the World, Part I,” “Spaceballs” and “Robin Hood: Men in Tights.”

A musical adaptation of “The Producers” ran on Broadway from 2001-07 and was remade into a musical film in 2005. A successful Broadway run started in 2007 for “Young Frankenstein,” which Brooks has called his best film. He continued to work into his 90s and published a memoir in 2021 titled “All About Me!: My Remarkable Life in Show Business.”

He married Florence Baum, a professional dancer with Broadway credits, in 1953. They had three children: Stephanie (b. 1956), Nicholas (b. 1957) and Edward (b. 1959). The marriage ended in 1962 and he married actress Anne Bancroft in 1964. They had a son, Maximilian (b. 1972), and were together until her death in 2005. In a 2021 interview, he called himself “very, very lucky” to be married to Bancroft. “And I, if I believed in God, I would thank God every night for giving me Anne Bancroft.” (NPR “Fresh Air,” Dec. 7, 2021)

He was asked in the interview if religion was “something you want at this point in your life, or are you remaining as secular as you’ve always been?” He replied: “Being afraid I’m going to die has not made me more religious. I’m still — I’m tribal. I love being a Jew, and I love Jewish humor, and I loved the — I don’t know, the je ne sais quoi that the Jews — they have a wonderful attitude. You know, I guess it’s called survival.”

PHOTO: Brooks at the premiere of the “Mel Brooks: Make A Noise” PBS documentary in 2013 in Beverly Hills, Calif.; s_bukley/Shutterstock.com

“If you’re not indoctrinated into some kind of religion when you’re very young, then it can play very little. I’m rather secular. I’m basically Jewish. But I think I’m Jewish not because of the Jewish religion at all. I think it’s the relationship with the people and the pride I have.”

— Brooks on what role religion plays in life, Men's Journal (June 2013)