educators

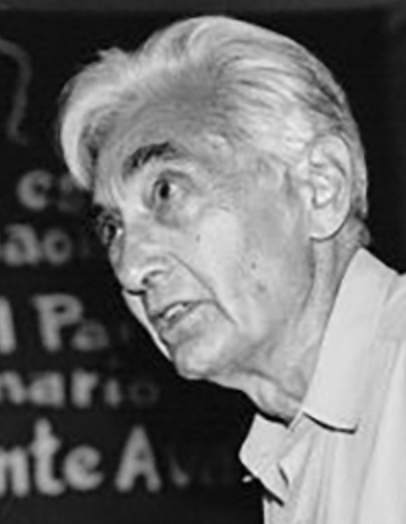

Francisco Ferrer

On this date in 1859, Spanish freethinker and educator Francisco Ferrer i Guàrdia was born on a farm near Barcelona. While his parents were pious Catholics, he was influenced by the anti-clerical views of his freethinking uncle and an early employer, which led him to support left-wing causes, including efforts to end Spain’s monarchy.

As a conductor on a train between Barcelona and France, Ferrer secretly sent messages for an exiled Republican leader and helped political refugees escape. After a Republican uprising failed in 1895, he fled with his wife Teresa and three daughters to Paris, where they lived for the next 16 years and he joined various socialist and anarchist causes while teaching Spanish and selling wine on commission.

A substantial inheritance enabled Ferrer to return in 1901 to Barcelona, where he started the Escuela Moderna, openly defying the monarchy and the Catholic dogmatic education system that saturated Spain. At the time, about half of Spaniards were illiterate. One report said the school “championed traits of reason, dignity, self-reliance and scientific observation over that of piety and obedience.”

Ferrer’s school had a printing press that printed dogma-free textbooks and radical tracts. Branches were opened in several cities and then internationally. In 1906, a young man who operated the press tried and failed to assassinate King Alfonso XIII. Ferrer was charged as a conspirator and his schools were closed.

Eventually freed for lack of evidence, Ferrer toured Europe, giving speeches and founding the International League for the Rational Education of Children. In 1909, after the renewed colonial war in Morocco provoked riots and a general strike, he was blamed for fomenting the rebellion and sentenced to death by firing squad. Historian Paul Avrich later called the case a “judicial murder” carried out to dispose of an agitator whose ideas threatened the status quo.

After Ferrer’s execution at age 50, Pope Pius X sent a gold-handled sword engraved with congratulations to the military prosecutor. (D. 1909)

“Science has shown that the story of the creation is a myth and the gods legendary.”

“When the masses become better informed about science, they will feel less need for help from supernatural Higher Powers. The need for religion will end when man becomes sensible enough to govern himself.”— Ferrer, quoted in "The Modern School Movement: Anarchism and Education in the United States" by Paul Avrich (1980) Second quote: Ferrer, quoted in "The Encyclopedia of Unbelief" (ed. Gordon Stein, 1985)

Peter Annet (Died)

On this date in 1769, “blasphemer” Peter Annet died. Born in 1693, he became a schoolmaster in Liverpool. In 1739 he wrote and published a pamphlet, “Judging for Ourselves, or Freethinking the Great Duty of Religion,” a strong criticism of Christianity. For writing this and similar pamphlets, he lost his position. Annet moved to London, where he became an outspoken member of the Robin Hood Society, a public debating society.

Annet, in his Resurrection of Jesus (1744), advanced the hypothesis of the illusory death of Jesus and suggested that perhaps Paul should be regarded as the founder of Christianity. In Supernaturals Examined (1747), Annet denied the possibility of miracles.

He was convicted of publishing “blasphemies” in The Free Inquirer periodical, which he founded in 1761. At age 68, Annet was sentenced to the pillory and a year’s hard labor. He later started a school and is known for inventing a system of shorthand. (D. 1769)

Corliss Lamont

On this date in 1902, Corliss Lamont was born in Englewood, N.J. His father, Thomas W. Lamont, was a chairman of J.P. Morgan & Co. He attended Phillips Exeter Academy and received his bachelor’s degree from Harvard University in 1924. He went on to obtain his Ph.D. in philosophy from Columbia University in 1932. Lamont supported many radical causes, including socialism, and although he never joined the Communist Party, he was strongly opposed to the persecution of communists.

He served as the director of the the American Civil Liberties Union from 1932 until 1954. He was a founder in 1954 of the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee. After being called before the House Un-American Activities Committee because of a book he had written, The Peoples of the Soviet Union (1946), he was cited for contempt of Congress. The indictment was dismissed by the Court of Appeals on the grounds that he was outside the jurisdiction of the committee.

Lamont wrote many books, pamphlets and essays, including many on humanism. His influential book The Philosophy of Humanism (1949), was based on a course he taught at Columbia in the 1940s and 1950s on naturalistic humanism. Other books on humanist subjects include his classic The Illusion of Immortality (1935), which argued against the imortality of the soul. He also wrote A Humanist Funeral Service (1954) and A Humanist Wedding Service (1970).

He was an active member for many years of the American Humanist Association and in 1977 received its Humanist of the Year award. He died of heart failure at age 93 in 1995.

“The greatest difference between the Humanist ethic and that of Christianity and the traditional religions is that it is entirely based on happiness in this one and only life and not concerned with a realm of supernatural immortality and the glory of God. Humanism denies the philosophical and psychological dualism of soul and body and contends that a human being is a oneness of mind, personality, and physical organism. Christian insistence on the resurrection of the body and personal immortality has often cut the nerve of effective action here and now, and has led to the neglect of present human welfare and happiness.”

— Lamont, “The Affirmative Ethics of Humanism,” The Humanist (March/April 1980)

Steven Weinberg

On this date in 1933, Steven Weinberg was born in the Bronx, N.Y. He received his undergraduate degree in physics from Cornell University in 1954, which he attended on a scholarship. There he met his future wife, Louise Goldwasser. They married in 1954. She became a professor of law at the University of Texas. Weinberg began his graduate study at the Institute for Theoretical Physics in Copenhagen (now the Niels Bohr Institute). He completed his Ph.D. at Princeton in 1957.

In 1979 Weinberg was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics along with Abdus Salam and Sheldon Lee Glashow “for their contributions to the theory of the unified weak and electromagnetic interaction between elementary particles, including, inter alia, the prediction of the weak neutral current.” This was one of the most significant scientific advances in the second half of the 20th century.

He received many other awards, including the national Medal of Science in 1991. He was also a foreign member of the Royal Society of London. Known for his writing, Weinberg received the Lewis Thomas Prize, which is awarded to the researcher who best embodies “the scientist as poet.”

Weinberg wrote hundreds of scholarly articles and textbooks such as The Quantum Theory of Fields (three volumes: 1995, 1996, 2003) and Cosmology (2008); the more popular works The First Three Minutes: A Modern View of the Origin of the Universe (1977) and Dreams of a Final Theory (1993, which contains a chapter called “What About God?”). His collection Facing Up: Science and its Cultural Adversaries was published in 2001, and Lake Views: This World and the Universe in 2011.

Weinberg was outspoken about his lack of religion and encouraged other scientists to be more vocal in their opposition to religious ideas. He said, “As you learn more and more about the universe, you find you can understand more and more without any reference to supernatural intervention, so you lose interest in that possibility. Most scientists I know don’t care enough about religion even to call themselves atheists. And that, I think, is one of the great things about science — that it has made it possible for people not to be religious.” (Quoted in Natalie Angier, “Confessions of a Lonely Atheist,” The New York Times, Jan. 14, 2001)

He added, “The whole history of the last thousands of years has been a history of religious persecutions and wars, pogroms, jihads, crusades. I find it all very regrettable, to say the least.” Five years later at a forum at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego, he said: “Anything that we scientists can do to weaken the hold of religion should be done and may in the end be our greatest contribution to civilization.” (New York Times, Nov. 21, 2006)

In 1999 he became the first recipient of FFRF’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award, reserved for public figures who make known their dissent from religion. He began his acceptance speech: “I enjoy being at a meeting that doesn’t start with an invocation!” He said, “Nothing has been more important in the history of science than the work of Darwin and Wallace pointing out that not only the planets but even life can be understood in this naturalistic way.” More excerpts from his speech can be found here.

He died at age 88 at a hospital in Austin and was survived by his wife Louise and their daughter Elizabeth. (D. 2021)

“Religion is an insult to human dignity. With or without it you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion.”

— Weinberg address at the Conference on Cosmic Design, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington (April 1999)

Christopher Cameron

On this date in 1983, historian Christopher Cameron was born on a U.S. Army base in Heidelberg, Germany, where his mother Sylvie Cameron was stationed. The oldest of five children, he grew up primarily in New Hampshire, where his Catholic and French-Canadian family had migrated to in the early 1960s.

What little religious upbringing he had revolved mostly around attending midnight Mass on Christmas Eve or Mass on Easter. That changed soon after he was incarcerated in 2001 on multiple drug charges and he became a born-again Christian, although after release he rarely if ever attended church.

Studying the works of Jiddu Krishnamurti, Daniel Dennett, Richard Dawkins and other philosophers and secular writers during his years in graduate school led to his embrace of atheism. He received his B.A. in history from Keene State College in New Hampshire and his M.A. and Ph.D. in American history from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Cameron is a scholar of atheism and freethought more broadly as well as being an atheist. As a professor of history at UNC-Charlotte, he teaches courses on freethought, American intellectual history and African American history. He was the founding president of the African American Intellectual History Society.

He’s the author of “To Plead Our Own Cause: African Americans in Massachusetts and the Making of the Antislavery Movement” (2014) and “Black Freethinkers: A History of African American Secularism” (2019). He co-edited “New Perspectives on the Black Intellectual Tradition” (2018) and “Race, Religion, and Black Lives Matter: Essays on a Moment and a Movement” (2021).

Cameron lives in Charlotte with his wife Shanice, his oldest child Cassidy and his twins Caleb and Callie. His speech to FFRF’s 2021 convention attendees is here.

“Despite views of Blacks as naturally religious, freethought has been a vital and significant component of Black culture and politics since the 19th century.”

— Cameron remarks at FFRF’s national convention in Boston (Nov. 20, 2021). Photo by Ingrid Laas.

Peter Singer

On this date in 1946, Peter Albert David Singer, philosopher, ethicist, animal rights activist and author was born in Melbourne, Australia. His Jewish parents fled Vienna in 1938 to escape the Nazi takeover. He earned his M.A. from the University of Melbourne in 1969 and got his B. Phil. at the University of Oxford in 1971. In 1977, Singer was appointed to a chair of philosophy at Monash University in Melbourne and subsequently was the founding director of that university’s Centre for Human Bioethics.

Singer was the founding president of the International Association of Bioethics, and with Helga Kuhse, founding co-editor of the journal Bioethics. In 1999 he accepted a professorship at Princeton University and is the DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at the University Center for Human Values at Princeton. He became well-known internationally after the publication of Animal Liberation in 1975.

His influential publications include Practical Ethics (1979), Hegel (1982), The Reproduction Revolution (1984, with Deane Wells), Should the Baby Live? (1985, with Helga Kuhse), How Are We to Live? (1993), Rethinking Life and Death (1994), A Darwinian Left (1999), One World (2000), The President of Good and Evil: The Ethics of George W. Bush (2004), Stem Cell Research: The Ethical Issues (2007), The Life You Can Save: Acting Now to End World Poverty (2009), The Most Good You Can Do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically (2015) and Ethics in the Real World: 82 Brief Essays on Things That Matter (2016).

As a student at the University of Melbourne, Singer was president of the Rationalist Society and editor of its publication The Freethinker. Singer frequently asserts that morality and ethics have no correlation to religious belief. “Atheists and agnostics do not behave less morally than religious believers, even if their virtuous acts rest on different principles. Non-believers often have as strong and sound a sense of right and wrong as anyone, and have worked to abolish slavery and contributed to other efforts to alleviate human suffering.” (Project Syndicate, “Godless Morality,” January 2006.)

He condemns religious intrusion into politics and scientific research. At FFRF’s annual convention in 2004, Singer was a recipient of the Emperor Has No Clothes Award. During his acceptance speech, he said, “Having come to live in America five years ago, I can clearly see why an organization like FFRF is very much needed.”

PHOTO: Singer at the Melbourne Effective Altruism conference in 2015; Mal Vickers photo under CC 4.0.

“I don’t believe in the existence of God, so it makes no sense to me to say that a human being is a creature of God. It’s as simple as that.”

— Singer, Religion & Ethics online magazine (Sept. 10, 1999)

Oliver Sacks

On this date in 1933, neurologist and author Oliver Sacks was born in London to a Jewish couple: Samuel Sacks, a medical general practitioner, and Muriel Elsie Landau, one of England’s first female surgeons. He earned his medical degree at Oxford University (Queen’s College) and did residencies and fellowship work at Mount Zion Hospital in San Francisco and at UCLA. He started practicing neurology in 1965 in New York, while maintaining his British citizenship. In July 2007 he was appointed professor of neurology and psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center.

In 1966 he had started working as a consulting neurologist for Beth Abraham Hospital in the Bronx, a chronic care hospital where he encountered an extraordinary group of patients, many of whom had spent decades in strange, frozen states, like human statues, unable to initiate movement. He recognized these patients as survivors of the pandemic of sleeping sickness (encephalitis lethargica) that swept the world from 1916-27 and treated them with a then-experimental drug, L-dopa. They became the subjects of his book Awakenings, which later inspired a play by Harold Pinter (“A Kind of Alaska”) and the Oscar-nominated feature film (“Awakenings”) with Robert De Niro and Robin Williams.

Sacks was perhaps best known for his collections of case histories from the far borderlands of neurological experience, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and An Anthropologist on Mars, in which he describes patients struggling with conditions ranging from Tourette’s syndrome to autism, parkinsonism, musical hallucination, epilepsy, phantom limb syndrome, schizophrenia, retardation and Alzheimer’s disease. He investigated the world of deaf people and sign language in Seeing Voices and a rare community of people in The Island of the Colorblind. He wrote about his experiences as a doctor in Migraine and as a patient in A Leg to Stand On. His autobiographical Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood was published in 2001, followed by Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain in 2007.

Sacks’ work regularly appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Review of Books and various medical journals. The New York Times referred to Sacks as “the poet laureate of medicine” and in 2002 he was awarded the Lewis Thomas Prize by Rockefeller University, which recognizes the scientist as poet. He is an honorary fellow of both the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and holds honorary degrees from Oxford, the Karolinska Institute, Georgetown, Bard, Gallaudet, Tufts and the Catholic University of Peru.

In 2005 he received FFRF’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award. His acceptance speech was titled “Invasion of Irrationalism.” He also began serving in 2009 on the Foundation’s Honorary Board. Not the least of his honors is 2-mile-wide Asteroid 84928 Oliversacks, discovered in 2003 and named for him. In a piece in The New York Times (“The Sabbath,” Aug. 14, 2015, shortly before his death from cancer), Sacks revealed his mother’s response to learning that he, then a teen, was a (virginal) homosexual. His mother, one of 18 children in an Orthodox Jewish family, shrieked at him: “ ‘You are an abomination. I wish you had never been born.’ … The matter was never mentioned again, but her harsh words made me hate religion’s capacity for bigotry and cruelty.” (D. 2015)

“As I write, in New York in mid-December, the city is full of Christmas trees and menorahs. I would be inclined to say, as an old Jewish atheist, that these things mean nothing to me, but Hannukah songs are evoked in my mind whenever an image of a menorah impinges on my retina, even when I am not consciously aware of it.”

— Sacks, "Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain" (2007)

Helen Taylor

On this date in 1831, Helen Taylor was born in England. Her mother married John Stuart Mill in 1851. When her mother died seven years later, she took care of her esteemed stepfather and assisted Mill in writing his landmark Subjection of Women (1869). After his death in 1873, Taylor edited his Autobiography and Essays on Religion (1874). She was elected to the London School Board three times between 1876 and 1882 and championed disadvantaged children.

She agitated for abolition of school fees and for subsidized school meals and worked to stop abuses at industrial schools. In 1881 she joined the Social Democratic Federation, known as Britain’s first organized socialist political party. Taylor, a strong feminist and suffragist, attempted to run for Parliament in 1885 but her nomination papers were refused. (D. 1907)

“Religion should be taught by ministers of religion or by volunteer teachers, such as teachers of Sunday schools, and … the school master ought not to undertake the work of the clergyman, least of all when we have a church, the richest in the world, magnificently endowed to do its own work.”

— Helen Taylor (attributed, 1876)

Howard Zinn

On this date in 1922, historian, author and peace activist Howard Zinn was born in New York City to Jewish immigrants. As a 17-year-old, Zinn attended a political rally in Times Square at the urging of neighborhood Communists and was knocked unconscious by police. He joined the Army Air Corps in 1943, received an Air Medal and, upon returning home, placed his medal and military papers in a folder on which he wrote “Never again.”

Zinn attended New York University and received a doctorate in history from Columbia University. He became chair of the history and social sciences department of Spelman College, the historically black college for women in segregated Atlanta, in 1956. He participated in the civil rights movement, served on the executive committee for SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) and inspired many of his students, including Alice Walker.

Fired for “insubordination” from Spelman in 1963 (for his criticism of the school’s failure to participate in the civil rights movement), Zinn took a position teaching history at Boston University, which he held until retirement in 1988.

An aggressive and early opponent of the Vietnam War (and war in general) and champion of liberal causes, Zinn’s 1967 Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal, was the first book calling for immediate withdrawal from the war with no exceptions. His A People’s History of the United States, published in 1980 with a small printing and little promotion, was a best-seller, hitting 1 million in sales by 2003. In his 1994 autobiography You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, Zinn wrote, “I wanted students to leave my classes not just better informed, but more prepared to relinquish the safety of silence, more prepared to speak up, to act against injustice wherever they saw it.”

While his publications were numerous, some of the highlights include the plays “Emma” (1976), about radical feminist and atheist Emma Goldman, “Daughter of Venus” (1985) and “Marx in Soho: A Play on History” (1999), and books such as Artists in Times of War (2003), History Matters: Conversations on History and Politics (2006), and Failure to Quit: Reflections of an Optimistic Historian (1993).

Zinn received the 1958 Albert J. Beveridge Prize from the American Historical Association for his book, LaGuardia in Congress; the 1998 Eugene V. Debs Award from the Debs Foundation; the Upton Sinclair Award in 1999; and the 1998 Lannan Literary Award. Zinn’s wife and lifetime collaborator, Roslyn, died in 2008. Zinn died of a heart attack at age 87 while swimming in a hotel pool in Santa Monica, Calif. (D. 2010)

PHOTO:Zinn at the Pathfinder Bookstore in Los Angeles in 2000. CC 4.0

“If I was promised that we could sit with Marx in some great Deli Haus in the hereafter, I might believe in it! Sure, I find inspiration in Jewish stories of hope, also in the Christian pacifism of the Berrigans, also in Taoism and Buddhism. I identify as a Jew, but not on religious grounds. Yes, I believe, as Pascal said, ‘The heart has its reasons which reason cannot know.’ There are limits to reason. There is mystery, there is passion, there is something spiritual in the arts — but it is not connected to Judaism or any other religion.”

— Tikkun magazine interview, "Howard Zinn on Fixing What's Wrong" (May 17, 2006)

Bwambale Robert Musubaho

On this date in 1979, humanist activist and educator Bwambale Robert Musubaho was born in Kasese, Uganda. Orphaned at age 5 and baptized and confirmed in the Anglican Church, he was raised by his grandmother and worked during high school as a barber before receiving a scholarship to attend Kyambogo University in Kampala. He graduated in 1998 with a biology degree.

In a 2017 interview with Phil Zuckerman, Bwambale said he lost his religious faith in the early 2000s when he “started being skeptical about the natural world and things in it,” eventually embracing humanism. He’s the author of the book Orphans of Rwenzori: A Humanist Perspective.

In 2011 he founded the Kasese Humanist School for boys and girls ages 3-14. It welcomes children from all belief and nonbelief systems but is secular in nature and stresses reliance on the sciences and avoidance of “dogmas and indoctrinations which are prevalent in the majority of Ugandan communities. We embrace REASON and belief in things backed by empirical evidence, not myths, fairy tales and allegories.” The school has three very modest campuses and about 700 students.

In 2015, working with the Brighter Brains Institute in the U.S., Bwambale started what was said to be the world’s first atheist orphanage. BiZoHa Orphanage includes one of the humanist school’s campuses and a small acreage on which food crops are grown. An affiliated humanist center offers educational DVDs, documentary films and books and woman empowerment initiatives in tailoring, gardening and craft making.

Bwambale is married and has a son and daughter. He speaks English, Swahili and Luganda.

“I think humanism is within us and it’s inborn, nobody under the sun is born with religion. I think religion is something that is imposed on humanity by people who have hidden agendas.”

— Bwambale interview with Phil Zuckerman, Psychology Today (March 10, 2017)

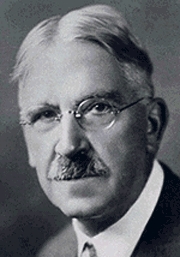

John Dewey

On this date in 1859, educator and philosopher John Dewey was born in Burlington, Vermont. He earned his doctorate at Johns Hopkins University in 1884. After teaching philosophy at the University of Michigan, he joined the faculty of the University of Chicago before moving to Columbia University in 1904. Dewey’s special concern was education reform. He promoted learning by doing rather than learning by rote.

Of his more than 40 books, many of his most influential concerned education, including My Pedagogic Creed (1897), Democracy and Education (1902) and Experience and Education (1938). He was one of the founders of the philosophy of pragmatism. A humanitarian, he was a trustee of Jane Addams‘ Hull House, supported labor and racial equality and was at one time active in campaigning for a third political party. He chaired a commission convened in Mexico City in 1937 inquiring into charges made against Leon Trotsky during the Moscow show trials.

Raised by an evangelical mother, Dewey had rejected faith by his 30s. Although he disavowed being a “militant” atheist, when his mother complained that he should be sending his children to Sunday school, he replied that he had gone to Sunday school enough to make up for any truancy by his children. As a pragmatist, he judged ideas by the results they produced. As a philosopher, he eschewed an allegiance to fixed and changeless dogma and superstition.

He sat on the advisory board of the First Humanist Society of New York, was one of the original 34 signatories of the first Humanist Manifesto in 1933 and was elected an honorary member of the Humanist Press Association in 1936. He once said that since he was not a theist, he thought that made him an atheist but he preferred to be known as a humanist.

Dewey married Harriet Alice Chipman in 1886 shortly after she graduated with a bachelor of philosophy degree from the University of Michigan. They had six children and adopted another. After she died from cerebral thrombosis in 1927. Dewey married Estelle Roberta Lowitz Grant in 1946 and they, despite Dewey being 87, adopted two siblings.

He died of pneumonia at home in New York City at age 92. (D. 1952)

“[H]ave not some religions, including the most influential forms of Christianity, taught that the heart of man is totally corrupt? How could the course of religion in its entire sweep not be marked by practices that are shameful in their cruelty and lustfulness, and by beliefs that are degraded and intellectually incredible?”

— Dewey, quoted in "Intelligence in the Modern World: John Dewey's Philosophy," ed. Joseph Ratner (1939)

Andrew Dickson White

On this date in 1832, Andrew Dickson White was born in Homer, N.Y. He graduated from Yale University in 1853 with a B.A. and returned for his M.A. in history in 1856. He became a history professor at the University of Michigan in 1856 and was elected a New York state senator in 1864. White co-founded Cornell University with Ezra Cornell and became its first president (1866-85). White was also the first president of the American Historical Association (1884-86), president of the American delegation to the Hague Peace Conference in 1899 and U.S. ambassador to Germany (1897-1902).

In 1859 he married Mary Outwater, who died in 1887. White married Helen Magill in 1890. He had four children.

Upon founding Cornell, White announced that he wanted the college to be “an asylum for Science — where truth shall be sought for truth’s sake, not stretched or cut exactly to fit Revealed Religion.” (God and Nature by David Lindberg and Ronald Numbers, 1986) He strongly supported science and secularism, lecturing about “The Battle-Fields of Science,” which he describes in his autobiography as a lecture about “how, in the supposed interest of religion, earnest and excellent men, for many ages and in many countries, had bitterly opposed various advances in science and in education.” (Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White Vol. 1, 1904)

In 1896 White wrote A History of the Warfare of Science and Theology in Christendom, which further examined the tumultuous relationship between science and religion. He wrote, “In all modern history, interference with science in the supposed interest of religion, no matter how conscientious such interference may have been, has resulted in the direst evils both to religion and science.” (D. 1918)

“I simply try to aid in letting the light of historical truth into that decaying mass of outworn thought which attaches the modern world to mediaeval conceptions of Christianity.”

— White, "A History of the Warfare of Science With Theology in Christendom" (1896)

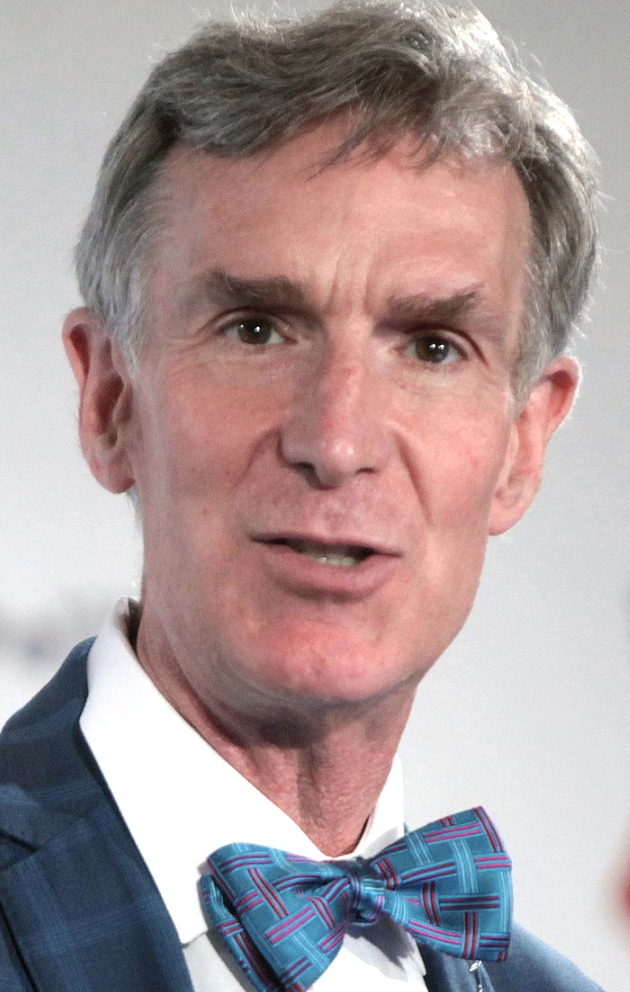

Bill Nye

On this date in 1955, William Sanford “Bill” Nye was born in Washington, D.C., where he was also raised. Nye, “America’s stand-up scientist,” says on his website that his parents fostered his interest in science. His father was a prisoner of war during World War II and his mother was a Navy codebreaker who excelled in math and science. In 1977 Nye earned a degree in mechanical engineering from Cornell University, where one of his professors was Carl Sagan. He then moved to Seattle to work as an engineer at Boeing.

Nye invented a special sundial used during the Mars Exploration Rover mission and engineered a hydraulic device for Boeing still used on the 747. During this time, Nye cultivated his comedy style, working nights as a stand-up comic and eventually quitting Boeing to work as a comedy writer and performer. He founded the educational television series “Bill Nye the Science Guy” (1993-98). The show won 18 Emmys in its five-year run.

Nye has written two best-selling books on science: Undeniable: Evolution and the Science of Creation in 2014 and Unstoppable: Harnessing Science to Change the World in 2015. Nye has appeared on “Dancing With the Stars,” “The Big Bang Theory,” “Inside Amy Schumer” and in a documentary about his life and science advocacy titled “Bill Nye: Science Guy,” which premiered at the South by Southwest Film Festival in March 2017 in Austin, TX. In 2017 he debuted the Netflix series “Bill Nye Saves the World.”

Nye was married in 2006 by Saddleback Church pastor Rick Warren to classical musician Blair Tindall but the union was annulled after less than a year. Nye in 2017 revealed his family’s history of ataxia, a neurological condition affecting coordination, saying he chose not to have children to avoid passing on the genetic condition.

PHOTO: Nye speaking at Politicon in 2016 in Pasadena, Calif. Gage Skidmore photo. CC 3.0.

“[I]t’s fine if you as an adult want to run around pretending or claiming that you don’t believe in evolution, but if we educate a generation of people who don’t believe in science, that’s a recipe for disaster. … The main idea in all of biology is evolution. To not teach it to our young people is wrong.”

— "Science Guy Bill Nye Explains Why Evolution Belongs in Science Education," Popular Mechanics (Feb. 4, 2011)

Titus Voelkel

On this date in 1849, freethinker Titus Voelkel was born in Germany. He studied theology, as well as science and mathematics, lived in Paris, then returned to Germany to teach at the secondary school level for a decade. In the 1880s, Voelkel became notorious as a rationalist lecturer. In 1885, he became editor of the Neues Freireligioses Sonntags-blatt. He was prosecuted and acquitted for blasphemy five times between 1887-88. Finally, in 1891, he was found guilty and spent two years in prison. Voelkel was later a deputy to the International Freethought Congress.

After emigrating to the U.S., he taught at City College of New York. A college publication from 1903 noted he would be receiving a $100 annual raise as a tutor in the Department of German Language and Literature. A college notice in 1913 announced he had resigned the presidency of the language association Deutscher Sprachverein and would serve as honorary president. (D. 1916)

“Dr. Titus Voelkel, the well-known free-thought agitator of North America, will soon arrive in Buffalo and will present two or three of his lectures. His subjects will be: ‘The Blessings of Infidelity,’ ‘Christianity and Socialism,’ and ‘Immortality.’ ”

— March 1901 ad in a newspaper in Buffalo, N.Y. "Socialism: Its Theoretical Basis and Practical Application" (1904)