October 19

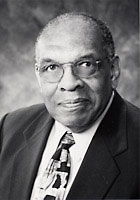

Alton Lemon

On this date in 1928, Alton Lemon, who would go on to win a major state/church victory before the U.S. Supreme Court, was born in McDonough, Ga. He grew up in Atlanta. As a youth, he played on the same basketball team as Martin Luther King Jr. He obtained a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from Morehouse College in 1950. He was an aerospace engineer for the Naval Air Development Center in Pennsylvania, and an automotive design engineer at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Aberdeen, Md.

Lemon also worked as an Equal Opportunity Officer for the U.S. Department of Energy. He was a citizen participation adviser for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, and he was at one time the program director for the North City Congress Police-Community Relations Program in Philadelphia. He also served in the U.S. Army and saw duty in the Korean War.

He served both as president and vice president of the Philadelphia Ethical Society, on the board of the Parents Union for Public Schools and was an active participant in the American Civil Liberties Union. He was married to Augusta Lemon for over 50 years.

Lemon was an “honorary officer” of the Freedom From Religion Foundation, a position reserved for freethinkers who have won Supreme Court cases in favor of the separation of church and state. He received a Hero of the First Amendment Award at the 2003 FFRF convention (although health problems at the last minute prevented him from accepting it in person).

He won the case Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), which successfully challenged a Pennsylvania law, the first such law in the nation providing public tax funds to religious schools for teaching four secular subjects. As a member of the ACLU, he volunteered to challenge the law, which resulted in a decision that is a watershed for the Establishment Clause, and which historic decision bears his name. The Supreme Court unanimously invalidated the parochial aid.

In one of the enduring legacies of the Burger Court, it also codified existing precedent on the Establishment Clause into a test called the Lemon Test. This was not new law, per se, but a kind of noble attempt to clarify and make the Establishment Clause idiot-proof. The Lemon Test has been invoked in virtually every lawsuit FFRF has ever taken. Despite attacks against it and attempts to modify and chip away at it, the Lemon Test endures. It is our best friend. (D. 2013)

If any of the three prongs of the Lemon Test are violated by an act of government, it is unconstitutional:

1) It must have a secular legislative purpose.

2) Its principal or primary effect must neither advance nor inhibit religion.

3) It must not foster excessive entanglement between government and religion.— The Lemon Test, promulgated in Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 US 602 (1971)

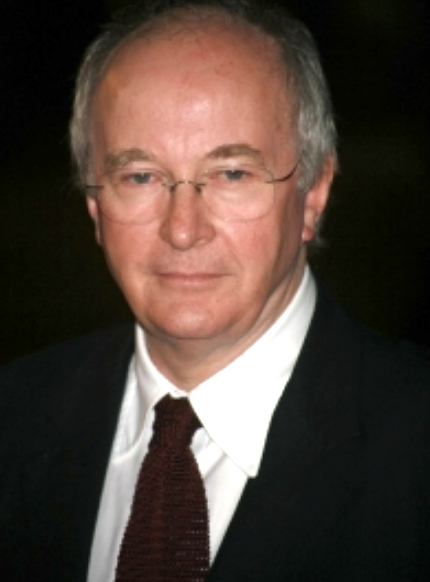

Philip Pullman

On this date in 1946, acclaimed author Philip Pullman was born in Norwich, England, into a Protestant family. Although his beloved grandfather was an Anglican priest, Pullman became an atheist in his teenage years. He graduated from Exeter College in Oxford with a degree in English and spent 23 years as a teacher while working on publishing 13 books and numerous short stories. Pullman has received many awards for his literature, including the prestigious Carnegie Medal for exceptional children’s literature in 1996, and the Carnegie of Carnegies in 2006.

He is most famous for the His Dark Materials trilogy, a series of young adult fantasy novels which feature freethought themes. The novels cast organized religion as the series’ villain and were written as a secular alternative to C.S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia. Pullman told The New York Times in 2000: “When you look at what C.S. Lewis is saying, his message is so anti-life, so cruel, so unjust. The view that the Narnia books have for the material world is one of almost undisguised contempt. At one point, the old professor says, ‘It’s all in Plato’ — meaning that the physical world we see around us is the crude, shabby, imperfect, second-rate copy of something much better. I want to emphasize the simple physical truth of things, the absolute primacy of the material life, rather than the spiritual or the afterlife.”

In 2007 the first novel of His Dark Materials trilogy was adapted for the motion picture “The Golden Compass” by New Line Cinema. Many churches and Christian organizations, including the Catholic League, called for a boycott of the film due to the books’ atheist themes. While the film was successful in Europe and moderately received in the U.S., the other two books in the trilogy were not adapted, possibly due to pressure from the Catholic Church.

When questioned about the anti-church views in His Dark Materials, Pullman explained in a February 2002 interview for the Third Way (UK): “Every single religion that has a monotheistic god ends up by persecuting other people and killing them because they don’t accept him. Wherever you look in history, you find that. It’s still going on.”

“I don’t profess any religion; I don’t think it’s possible that there is a God; I have the greatest difficulty in understanding what is meant by the words ‘spiritual’ or ‘spirituality.’ “

— Pullman interview, The New Yorker (Dec. 26, 2005)

Trey Parker

On this date in 1969, Trey Parker was born Randolph Severn Parker III in Denver, Colorado. He attended the Berklee School of Music before transferring to the University of Colorado at Boulder, where he studied film and music and met his long-time collaborator Matt Stone. After leaving school, Parker directed a film called “Cannibal! The Musical” (1993). Parker and Stone collaborated on various projects, including an animated short entitled “The Spirit of Christmas” (1996), in which Santa Claus and Jesus fight about the true meaning of Christmas (the answer is that the true meaning of Christmas is presents, not fighting).

This short led to a 1997 deal with Comedy Central to make “South Park,” an animated show starring four third-graders: Kyle, Stan, Cartman, and Kenny (characters first explored in the short), which is frequently satirical and often employs crude humor. Parker and Stone do most of the male characters’ voices themselves.

The show is set in the fictional town of South Park, Colorado. Parker and Stone made a movie in 1999 titled “South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut”. “South Park” has been nominated for several Emmys and has won Outstanding Animated Program three times. The three-part “Imaginationland” won 2008’s Emmy for Outstanding Animated Program. Parker is also a Tony winner with “The Book of Mormon,” another collaboration with Stone, winning nine Tonys in 2011, including Best Musical, Best Original Score and Best Book of a Musical.

Parker and Stone are not afraid to satirize sensitive subjects, including religion. Jesus (voiced by Stone) has appeared in many episodes, for example as a superhero and the leader of the Super Best Friends in an episode entitled “Super Best Friends,” which originally aired on July 4, 2001. This group also featured other religious figures, including Buddha, Lao Tse, Krishna, Joseph Smith, and Muhammed. (Islamic law traditionally prohibits visual depictions of their prophet.)

In 2006, Stone and Parker’s attempt to depict Muhammed in the two-parter “Cartoon Wars” in response to the Danish cartoon controversy was censored by Comedy Central. In the episode “200,” Muhammad is alleged to be totally hidden inside a bear suit inside a U-Haul. In Muhammad’s original portrayal on the show (in “Super Best Friends”), he was a superhero with the powers of flame; however, he had since gained the superpower of not being able to be made fun of, which Tom Cruise and other celebrities are shown trying to obtain for themselves in “200” and its follow-up, “201.” (Death threats over Muhammad’s portrayal in “201” received in 2010 led “Super Best Friends” to be pulled from syndication, four years after “Cartoon Wars” was censored.)

“All the religions are super funny to me. The story of Jesus makes no sense to me. God sent his only son. Why could God only have one son and why would he have to die? It’s just bad writing, really. And it’s really terrible in about the second act.”

— Parker interview with ABC "Nightline" (Sept. 22, 2006)

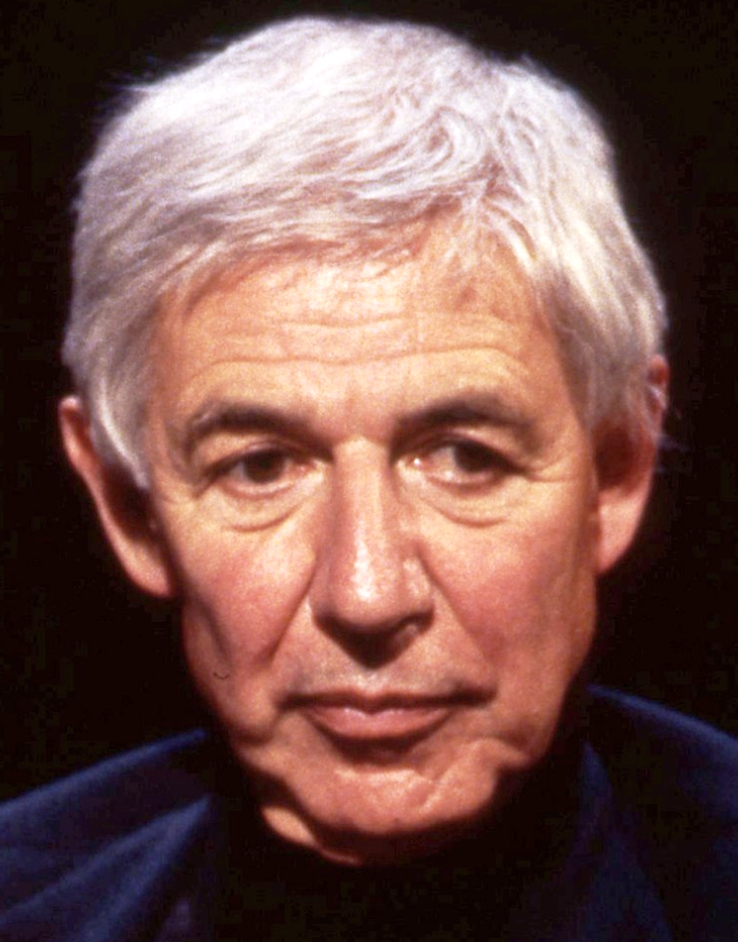

Lewis Wolpert

On this date in 1929, Lewis Wolpert was born into a Jewish family in Johannesburg, South Africa. He earned a degree in engineering from the University of Witwatersrand in 1950 and graduated from King’s College at the University of London with a Ph.D. in cell biology in 1961. He was a lecturer in zoology at King’s College from 1960-64 and became a professor of biology as applied to medicine at Middlesex Hospital Medical School 1966.

In 2010 he accepted emeritus status as a biology professor at University College London. He has several popular science books, including The Unnatural Nature of Science (1992), Malignant Sadness: The Anatomy of Depression (1999), Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast: The Evolutionary Origins of Belief (2006) and How We Live And Why We Die: The Secret Lives of Cells (2009). Wolpert was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1990.

After growing up Jewish, he became “a reductionist, materialist atheist,” according to an article in The Guardian (April 11, 2006). He wrote about his deconversion in Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast: “I was quite a religious child, saying my prayers each night and asking God for help on various occasions. It did not seem to help and I gave it all up around 16 and have been an atheist ever since.” In the book he states that religion arose from humans’ evolutionary predisposition to look for cause and effect relationships.

A vice president of the British Humanist Association, Wolpert has debated Christian apologist William Lane Craig about the existence of God, Christian astrophysicist Hugh Ross on whether there is a case for a creator and William Dembski on the topic of intelligent design.

He died at age 91 in England of COVID-related complications. (D. 2021)

PHOTO: Wolpert in 1994 under CC 4.0.

“I am committed to science and believe it to be the best way to understand the world. … I know of no good evidence for the existence of God.”

— Wolpert, "Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast" (2006)

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar

On this date in 1910, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar was born in Lahore, now in Pakistan but at the time a part of British India. He earned a B.S. with honors in physics from Presidency College in India in 1930 and a Ph.D. in physics from Cambridge University in England in 1933. After his graduation, Chandrasekhar was awarded a Prize Fellowship at Trinity College from 1933 to 1937. He worked as a research associate and professor at the University of Chicago from 1937 to 1995, and became an American citizen in 1953. He married Lalitha Doraiswamy in 1936.

Chandrasekhar was an astrophysicist who made influential discoveries about white dwarf stars in 1930 when he was only 20. He is known for discovering the Chandrasekhar limit. He found that stars with masses below the Chandrasekhar limit form white dwarfs after they collapse, but stars with masses above the limit continue collapsing. His studies of stellar evolution were influential in the discovery of black holes.

He won the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physics with William Fowler for their work with stellar structure and evolution. He published 10 books, including Introduction to the Study of Stellar Structure (1939), Principles of Stellar Dynamics (1942) and The Mathematical Theory of Black Holes (1983).

Chandrasekhar was the nephew of C. V. Raman, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1930. He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1953. A vegetarian, he died of a heart attack at age 84 at the University of Chicago Hospital, 20 years after his first heart attack. His wife died at age 102 in 2013. (D. 1995)

“I am not religious in any sense; in fact, I consider myself an atheist.”

— Chandrasekhar, quoted in "Chandra: A Biography of S. Chandrasekhar" by Kameshwar Wali (1991)

Neal Brennan

On this date in 1973, comedian-writer-director Neal Brennan was born in Villanova, Pa., the youngest of 10 children in an Irish-Catholic family. He studied film for a year at New York University, then worked as a doorman at a Greenwich Village comedy club where he met Dave Chappelle.

He moved to Los Angeles in the mid-1990s to write for television. He teamed with Chappelle in 1997 on the screenplay for the film “Half Baked,” a commercial failure that became a cult classic. He and Chappelle co-created the sketch comedy series “Chappelle’s Show” in 2002, which debuted in 2003 on Comedy Central and aired until 2006. Chappelle left the show without warning in 2005.

Brennan received three Emmy nominations for directing, writing and producing “Chappelle’s Show.” It’s the top-selling television show DVD of all time with nearly 9 million units sold as of this writing in 2019. It was Comedy Central’s highest-rated program after two seasons.

He also wrote material for “Saturday Night Live” when Chappelle and Aziz Ansari were hosts and for Seth Meyers’ speech at the White House Correspondents Dinner in 2011. His first one-hour stand-up special, “Women and Black Dudes” premiered on Comedy Central in 2014.

Brennan became a contributor to “The Daily Show with Trevor Noah” in 2016 as “Trevor’s friend Neal.” In 2017 he released “3 Mics,” his second special on Netflix, followed by an all-new half hour of material in 2019 as part of the Comedians of the World series.

An atheist, Brennan doesn’t mind taking potshots at it, calling it “the height of white privilege.” (The Hollywood Reporter, April 15, 2019): “Think about it: Religion basically says, ‘Hey, can we interest you in an after-life?’ And white people are all like, ‘No, thank you.’ Like, ‘Why, how much better can it be?’ ”

On Peter McGraw’s podcast (Sept. 26, 2018), Brennan said: “The only thing that matters to me now is the first-person experience. Legacy is hogwash to me, even any religion. I’ve been shaky at best on religion for the last decade.”

PHOTO: Brennan in 2012; photo by CleftClips under CC 2.0.

“God is unbelievable! (I’m an atheist)”

— Brennan tweet, July 10, 2011

Cara Santa Maria

On this date in 1983, journalist and science communicator Cara Louise Santa Maria was born in Plano, Texas. Her parents were raised Catholic but converted to Mormonism as adults. Santa Maria was baptized as a Latter-day Saint at age 8 but by age 15 had left the church and started identifying as an atheist.

She earned a B.S. in psychology from the University of North Texas in Denton in 2004, followed by an M.S. in neurobiology in 2007 and of this writing was working toward a Ph.D. in clinical psychology from Fielding Graduate University in Santa Barbara, Calif.

Santa Maria was laboratory manager and chief cell culture technician at the Center for Network Neuroscience at UNT. She also taught biology and psychology courses at the high school and undergraduate level. In 2009 she moved to the Los Angeles area to begin a career in science communication. She was senior science correspondent for the Huffington Post and later a correspondent on “Bill Nye Saves the World.”

Santa Maria co-produced and hosted a pilot titled “Talk Nerdy to Me” for HBO but it never aired. “Talk Nerdy” is the title of her weekly science podcast, which celebrated its sixth anniversary in March 2020. Atheism and politics are sometimes featured topics. She has been a science correspondent and guest on National Geographic’s TV series “Brain Games.” Since 2015 she has co-hosted “The Skeptics’ Guide to the Universe” podcast and co-wrote the 2018 book with that title.

On Earth Day 2017, she was an emcee at the March for Science in Washington, D.C. “Science is under attack,” she told the crowd. “The very idea of evidence and logic and reason is being threatened by individuals and interests with the power to do real harm.”

From 2009 to 2011, she was in a relationship with television host and political commentator Bill Maher but has never married. Neil deGrasse Tyson presented her with a 2014 Knight Foundation award for her efforts to make science clearer for a broad public audience.

She was the recipient in 2017 of FFRF’s Freethought Heroine award. She told convention attendees she remembers the day when she was 14 that her father told her “I have a moral obligation to God to force you to go to church until you’re 18 so long as you live under my roof.” Santa Maria replied, “Then maybe I won’t live under your roof anymore.” Her acceptance speech is here.

“I don’t believe in God.”

— Santa Maria remarks at FFRF’s 40th annual convention (Sept. 15, 2017)

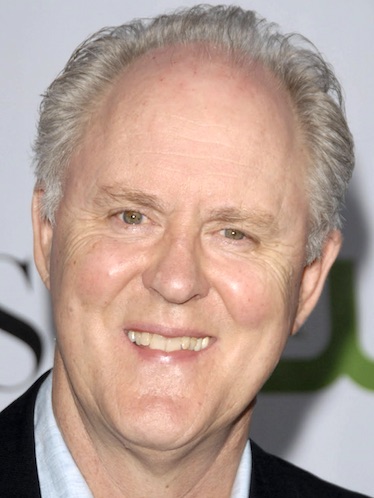

John Lithgow

On this date in 1945, actor John Arthur Lithgow was born in Rochester, N.Y., to Sarah Jane (née Price) and Arthur Lithgow III. His mother was an actress and his father was a theatrical producer and property manager. The family moved a lot due to his father’s work in theater production, including 10 years in Yellow Springs, Ohio, where for a time Coretta Scott, a college student and future wife of Martin Luther King Jr., babysat for the four Lithgow siblings.

“I’m not a religious person,” Lithgow explained later. “I grew up in eight different places. There was never even the opportunity to become part of a religious community, even if my family were so inclined, which they weren’t.” (Showbiz Cheatsheet, July 20, 2022)

The Lithgows lived in Akron, Ohio, in the early 1960s when Arthur was the first manager of the estate built for the Seiberling family, founders of the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. The huge home contained 64,500 square feet. Lithgow graduated from high school in Princeton, N.J. and enrolled at Harvard University, where he earned a B.A. in 1967 and then won a Fulbright Scholarship to the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art.

After a stint at WBAI, the Pacifica radio station in New York City, he made his film debut in “Dealing: Or the Berkeley-to-Boston Forty-Brick Lost-Bag Blues,” followed by playing a pivotal role in 1976 in Brian De Palma’s “Obsession” opposite Cliff Robertson and Genevieve Bujold. He had debuted on Broadway in “The Changing Room” (1972), which earned him his first Best Featured Actor Tony Award.

It was the fist among numerous plaudits he would garner, including six Emmys, two Golden Globes, two Tonys and nominations for two Academy Awards, a BAFTA Award and four Grammys. He appeared in Bob Fosse’s semi-autobiographical movie “All That Jazz” in 1979. His second Tony was for the musical “Sweet Smell of Success” in 2002.

While Lithgow’s 6-foot-4 frame made many small-screen appearances, his role as Dick Solomon in the TV sitcom “3rd Rock from the Sun” (1996–2001) is perhaps best known. It brought him three Primetime Emmys for Best Actor in a Comedy Series. He received further Primetime Emmys for Showtime’s “Dexter” (Season 4) and as Winston Churchill in the Netflix drama “The Crown” (2016–2019).

A small sampling of his dozens of other film roles — too numerous to mention them all — includes “The World According to Garp” (1982), “Terms of Endearment” and “Twilight Zone: The Movie” (1983), “Footloose” (1984), “The Manhattan Project” (1986), “Memphis Belle” (1990), “The Pelican Brief” (1993), “Shrek” (2001), “Kinsey” (2004), “Rise of the Planet of the Apes” (2011), “Love Is Strange” (2014), “Pet Sematary” (2019), “Killers of the Flower Moon” (2023) and “Conclave” (2024), in which he and Stanley Tucci portrayed Catholic cardinals.

Lithgow received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2001 and was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame in 2005 and the American Philosophical Society in 2019. He married Jean Taynton, a teacher, in 1966. They had a son Ian in 1972 and divorced in 1980. He married UCLA history professor Mary Yeager in 1981. They have a son Nathan and a daughter Phoebe.

Lithgow has done extensive work for children, including several books and three music albums. He took groups to performances of Brahms’ “Hungarian Dances” ballet and Tchaikovsky‘s “The Nutcracker” when he conducted the orchestra while children performed.

He presided in 2006 at the marriage of his goddaughter Nell Freudenberger in East Hampton, N.Y., as an officiant of Rose Ministries, which offers online ordinations regardless of religion, sexuality or race.

PHOTO: Lithgow in 2009 at the Huntington Library in Pasadena, Calif.; photo by Shutterstock/s_bukley.

“I think of death as death. I don’t think there’s life after death or a soul after death.”

— Lithgow on National Public Radio's "Wild Card" (Dec. 8, 2024)