September 21

H.G. Wells

On this date in 1866, (Herbert George) H.G. Wells was born to a working-class family in Kent, England. He received a spotty education, interrupted by several illnesses and family difficulties, and became a draper’s apprentice as a teen. Wells earned a government scholarship in 1884 to study biology under Thomas Henry Huxley at the Normal School of Science. Wells earned his bachelor of science and doctor of science degrees at the University of London.

After marrying his cousin Isabel, Wells began to supplement his teaching salary with short stories and freelance articles, then books, including The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897) and The War of the Worlds (1898). Wells created a mild scandal when he divorced Isabel to marry one of his best students, Amy Catherine Robbins. Although his second marriage was lasting and produced two sons, Wells was an unabashed advocate of free (as opposed to “indiscriminate”) love. He continued to openly have extramarital liaisons, most famously with Margaret Sanger, and a 10-year relationship with the author Rebecca West, who had one of his two out-of-wedlock children.

As a member of the socialist Fabian Society, Wells sought active change. His 100 books included nonfiction such as A Modern Utopia (1905), The Outline of History (1920), A Short History of the World (1922), The Shape of Things to Come (1933) and The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind (1932). One of his booklets was Crux Ansata, An Indictment of the Roman Catholic Church. Although Wells toyed briefly with the idea of a “divine will” in his book God the Invisible King (1917), it was a temporary aberration.

Wells used his international fame to promote his favorite causes, including the prevention of war, and was received by government officials around the world. He is best remembered as an early writer of science fiction and futurism. (D. 1946)

“Indeed Christianity passes. Passes — it has gone! It has littered the beaches of life with churches, cathedrals, shrines and crucifixes, prejudices and intolerances, like the sea urchin and starfish and empty shells and lumps of stinging jelly upon the sands here after a tide. A tidal wave out of Egypt. And it has left a multitude of little wriggling theologians and confessors and apologists hopping and burrowing in the warm nutritious sand. But in the hearts of living men, what remains of it now? Doubtful scraps of Arianism. Phrases. Sentiments. Habits.”

— Wells, "Experiment in Autobiography" (1934), cited by Ira D. Cardiff, "What Great Men Think of Religion" (1945)

Etta Semple

On this date in 1855, Etta Semple (née Martha Etta Donaldson) was born into a Baptist family in Quincy, Illinois. After being left a widow with two sons in 1887, she married Matthew Semple of Ottawa, Kansas, and they had one son. Etta became Ottawa’s town radical, espousing freethought, feminism, opposing racial bigotry, capital punishment and “blue laws.”

Her pro-working class novels included Society and The Strike. She helped found the Kansas Freethought Association to “fight ignorance, superstition and tyranny” and in 1879 was elected its president. She also served as vice president of the American Secular Union. From her parlor she published the bimonthly Freethought Ideal, an eight-page newspaper with a 2,000 circulation. She amused Ottawans in the summer of 1901 by strolling arm in arm with Carry Nation, prompting a local wag to quip: “One believes in no saloons, and one believes in no god.”

In 1902 she opened a “Natural Cure” sanitarium with 31 rooms. “No tramp ever went away hungry, and no fallen woman has been kicked down by us,” she wrote. While the Ottawa Evening Herald hailed her as a “Good Samaritan” and “one of the greatest benefactors Ottawa has ever had,” she was stalked by an assassin. In an unsolved murder on March 28, 1905, an elderly patient in the hospital was bludgeoned in bed. Semple was believed by authorities to be the intended victim.

When she died of pneumonia at age 59, court was adjourned and crowds filled the cemetery for a godless oration in the spring sun. The Evening Herald’s banner headline read “Good Deeds of A Good Woman Are on the Tongues of Ottawa Today.” The story added: “It was the biggest funeral Ottawa had ever seen. It was also perhaps the most unusual. No minister spoke. No hymns were sung, no flowers decorated the parlor.” Mourners sang one of her favorite secular songs, “Scattering Seeds of Kindness,” which the newspaper called “emblematic of Mrs. Semple’s life.” (D. 1914)

“I never yet have seen the person who could withstand the doubt and unbelief that enter his mind when reading the Bible in a spirit of inquiry.”

— Semple, "A Pious Congressman Twice Answered," The Truth Seeker (Feb. 23, 1895)

James Watson

On this date in 1799, James Watson, who became a much-imprisoned English freethought publisher, was born in Yorkshire. As a young worker in Leeds, he joined a radical reading club and became a freethinker. At age 23, Watson moved to London to assist publisher Richard Carlile at his shop, taking over when Carlile was imprisoned in 1822. Carlile had expressly opened the shop to publish and sell periodicals that would challenge “Six Acts,” a suppressive law passed in 1819.

Watson was arrested in 1823 for selling Elihu Palmer’s Principles of Nature and was sentenced to a year at Cold Bath Fields prison for blasphemy. He took advantage of his confinement to read rationalist writers. Released in April 1824, he learned the skills of the printing trade directly from Carlile and also worked for another radical publisher, Julian Hibbert. In 1827, Watson joined the Owenites (see Robert Owen), and became an agent for Owens’ Cooperative Trading Association.

In 1830 Watson opened his own publishing house, specializing in handprinted and bound-volume classics by freethinkers. In 1831 he organized a feast to counter a government-ordered fast. In 1832 he began publishing the Working Man’s Friend, an unstamped newspaper (stamp laws had a chilling effect on publishers of newspapers and pamphlets), for which he was sent to prison for six months in 1833. For selling the Poor Man’s Guardian, another newspaper sympathetic to workers, Watson was imprisoned for six months in 1834-35. In the 1840s he campaigned against blasphemy laws and, with G.J. Holyoake, published the anti-Christian journal The Reasoner. (D. 1874)

“I am happy that I can aid those admirable men, both living and dead, who by their pens or their tongues have aided the great cause of human liberty and universal happiness.”

— Watson, "A Voice from the Bastille" (Feb. 23, 1833)

Sir Bernard Williams

On this date in 1929, English moral philosopher Sir Bernard Arthur Owen Williams was born in Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex, to Hilda (Day) and Owen Williams. His mother was a personal assistant and his father was chief maintenance surveyor for the Ministry of Works.

He was educated at Chigwell School, Essex, and Balliol College, Oxford (B.A. 1951, M.A. 1954). “Virtually the only subject in which one could ever get a scholarship to Oxford or Cambridge was classics,” he later wrote. “So I went to Oxford to study classics and, unlike Cambridge, it had a philosophy component and I became completely transported by it.” (The Guardian, Nov. 30, 2002)

His national service was spent flying Spitfire fighter planes in Canada for the Royal Air Force, after which he returned to Oxford to become a fellow at its New College. In 1955 he married Shirley Brittain, whom he met while both were taking classes at Columbia University in New York. They had a daughter, Rebecca, in 1961 after four miscarriages before the marriage ended in 1974 when the Catholic Church annulled it at Shirley’s request despite its 19-year length.

“While Shirley was (and is) a devout Catholic and so took the marriage as a commitment for eternity, Bernard, an atheist, had not done so when he made the wedding vows,” stated The Guardian’s 2002 story. According to her, “The Church and Bernard had a wonderful time debating all this. The theologians were so thrilled to be discussing it with a leading philosopher. … I was influenced by Christian thinking, and he would say ‘That’s frightfully pompous and it’s not really the point.’ So we had a certain jarring over that and over Catholicism.”

She would go on to lead the Liberal Democrats in the House of Lords and was married for 16 years to American political scientist Richard Neustadt, who died in 2003 (four months after Bernard Williams died). Earlier, as a Member of Parliament, she was not liberal on reproductive choice, being one of only two women in the House of Commons to vote against legalizing abortion in 1967.

Williams had started living with Patricia Law Skinner in 1971 and they wed soon after his marriage was dissolved. She was philosophy editor at Cambridge University Press. They had two sons, Jacob (b. 1975) and Jonathan (b. 1980).

Williams lectured and held professorships at several universities while publishing widely during this period. His first book was “Morality: An Introduction to Ethics” (1972), termed by The Guardian as “an incendiary critique of British philosophy’s obsession with meta-ethical questions … at the expense of first-order ethical questions concerning abortion, famine and feminism.” He was a strong supporter of women in academia.

“He might be described as an analytical philosopher with the soul of a general humanist,” wrote Colin McGinn in the New York Review of Books (April 10, 2003). “He opposes the widespread contemporary desire to model philosophy on science, preferring to locate philosophy within its historical and cultural context.”

“He argued in a later book, ‘Shame and Necessity’ (1993), a study of ancient Greece, that Hellenic ethics allowed for a wider scope of praise and blame than did Christian-based morality, concluding that the sense of shame can be more in tune with our intuitions than moral guilt, and permits more latitude for living a whole life well.” (New York Times obituary, June 14, 2003)

Williams became a member of the Institut international de philosophie in 1969, a fellow of the British Academy in 1971, an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1983 and was knighted in 1999. He died of heart failure at age 73 while on vacation in Rome, where he was cremated. (D. 2003)

“He regarded as incoherent the idea of a God who is above space and time and yet communicates with us who live in space and time.”

— Jonathan Sacks, theologian and rabbi, commenting on Williams (The Times of London, June 17, 2003)

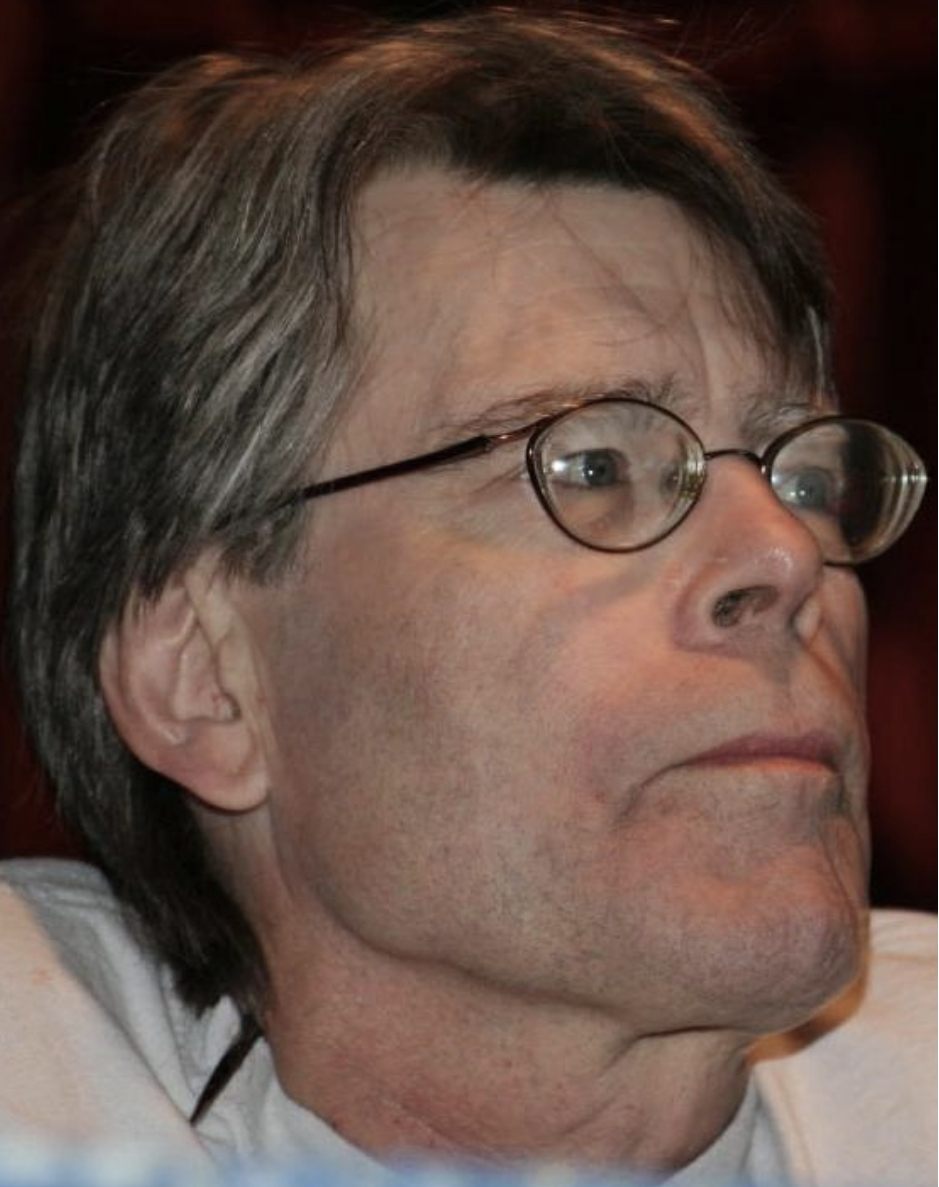

Stephen King

On this date in 1947, best-selling suspense novelist Stephen King was born in Portland, Maine. King’s parents split when he was a toddler, and he and his older brother were raised by their mother, who struggled financially. Though he grew up attending a Methodist church, his doubts about organized religion began at an early age. In a 2013 interview with National Public Radio on whether he believed in God, King said “the jury’s out on that,” adding that while at the moment he chose to believe, he reserved the right to change his mind.

He sold “The Glass Floor,” his first professional short story, to Startling Mystery Stories in 1967. He attended the University of Maine at Orono and wrote a weekly column for the school paper, served as a member of the Student Senate, opposed the Vietnam War and graduated in 1970 with a B.A. in English. In 1971 he married Tabitha Spruce, whom he met while working at a library. King taught English at Hampden Academy in Hampden, Maine, and pursued his writing in the evenings and on the weekends. King’s first novel, Carrie, was accepted by Doubleday & Co. in 1973. Due to its success, he was able to leave his teaching job and write full time.

King has published 60 novels, including seven under the pen name Richard Bachman, and five nonfiction works. He has written over 200 short stories, most of which have been compiled in book collections. His books have sold more than 350 million copies, and many of them have been adapted into feature films, TV movies and comic books. Many of his books contain overt religious themes, which prompted America’s Dark Theologian: The Religious Imagination of Stephen King (2018), by Douglas E. Cowan.

King and his wife, also a novelist and philanthropist, annually give away about $4 million to libraries, fire departments, schools and organizations supporting the arts. They have a daughter, Naomi, who is a Unitarian Universalist minister in Florida, as is her domestic partner Thandeka, whose name means “beloved” and was given her by Bishop Desmond Tutu. Their sons, Owen and Joseph, are both writers.

King in 2007. Pinguino Kolb photo, Creative Commons.

“But as far as God and church and religion … I kind of always felt that organized religion was just basically a theological insurance scam where they’re saying if you spend time with us, guess what, you’re going to live forever, you’re going to go to some other plain where you’re going to be so happy, you’ll just be happy all the time, which is also kind of a scary idea to me.”

— Stephen King, interview, NPR's "Fresh Air" (May 28, 2013)

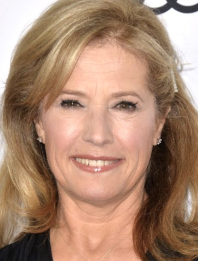

Nancy Travis

On this date in 1961, actress Nancy Ann Travis was born to Theresa and Gordon Travis in Queens, N.Y. Her mother was a social worker and her father was a sales executive. Raised in Baltimore and Framingham, Mass., Travis was bitten by the acting bug at age 7 while playing Wilbur the pig in “Charlotte’s Web” at her school. “When I got the lead, I was hooked.” (People magazine, Jan. 13, 2003)

That was also the age she made her First Communion as a Catholic. “Growing up, my mother wanted me and my brother to be raised with some kind of religious instruction, a point of reference that we could choose to accept or reject.” (Katie Couric Media, Nov. 24, 2023)

She graduated in 1983 with a bachelor of fine arts from New York University, then worked as a waitress while struggling to make it as an actress in New York City. She toured the country in 1984 as an understudy in “Brighton Beach Memoirs” and was a founding member of the Off-Broadway theater company Naked Angels. Her Broadway debut was in “I’m Not Rappaport” in 1985.

Travis’ screen debut was also that year in the made-for-TV biopic “Malice in Wonderland” starring Elizabeth Taylor and Jane Alexander about Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons. Her feature film debut was two years later in “Three Men and a Baby” opposite Tom Selleck, Steve Guttenberg and Ted Danson. Directed by Leonard Nimoy, it was a huge hit, grossing $240 million worldwide.

It was the start of a string of appearances in nearly 30 movies and short films. Most recently as of this writing, she appeared with Hilary Swank in “Ordinary Angels” (2024). Her work on the small screen in numerous series and movies starting in the mid-1990s also kept her busy, including 194 episodes of the ABC sitcom “Last Man Standing” opposite Tim Allen. She appeared in two seasons (2018-19) of “The Kominsky Method” on Netflix with Michael Douglas, Alan Arkin, Paul Reiser and Kathleen Turner.

A lead role in the 1990 Richard Gere drama “Internal Affairs” led to Travis meeting Robert Fried, executive vice president at Columbia Pictures: “He opened the door, and it was love at first sight.” They married in 1994 in a Jewish ceremony and have two sons, Benjamin (b. 1998) and Jeremy (b. 2001). (Ibid., People)

“I married a Jewish man for whom religion is not just worship, but his identity,” Travis later said. “I did not convert, but had rejected Catholicism and God.” She agreed to raise the children as Jewish, thinking they “should have something to embrace or scorn.”

She and her mother, an “adamant atheist,” had continued discussing religion and the existence of God into her adulthood. “I pivoted frequently: I’d disassociate myself from Catholicism and choose to call myself ‘spiritual’ instead. I would settle on God being an energy or life source rather than a bearded benevolent man at a judgment table.” (Ibid., Katie Couric)

In her extraordinary essay “My Mother Was an Atheist — These Days, I Understand Why,” Travis wrote that her mother, despite an Italian Catholic upbringing, thought “organized religion was ‘horseshit’ and had no problem saying so. Maybe it had to do with being diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis at a young age, with suffering so much chronic pain that God was only found in Vicodin.” (Ibid.)

Grieving after her mother’s death amid a world full of bloodshed and sectarian strife, Travis thought “She would not have been surprised to know that I did not turn to God for comfort, but to my family and friends who held me and helped me through my grief. Strength and empathy came from the people around me. The meaning I was searching for in God was really in my fellow human beings. For all the good and bad in life, at least we have each other. My mother didn’t believe in God, but she believed in people.”

PHOTO: Travis at the 2018 premiere of “The Kominsky Method” in Los Angeles; Shutterstock/Featureflash Photo Agency

“If my mother was still alive, I would tell her that I’m not so sure there is a God. But more importantly, I’d explain that I’m searching for our shared faith in humanity.”

— Travis essay, Katie Couric Media (Nov. 24, 2023)