October 25

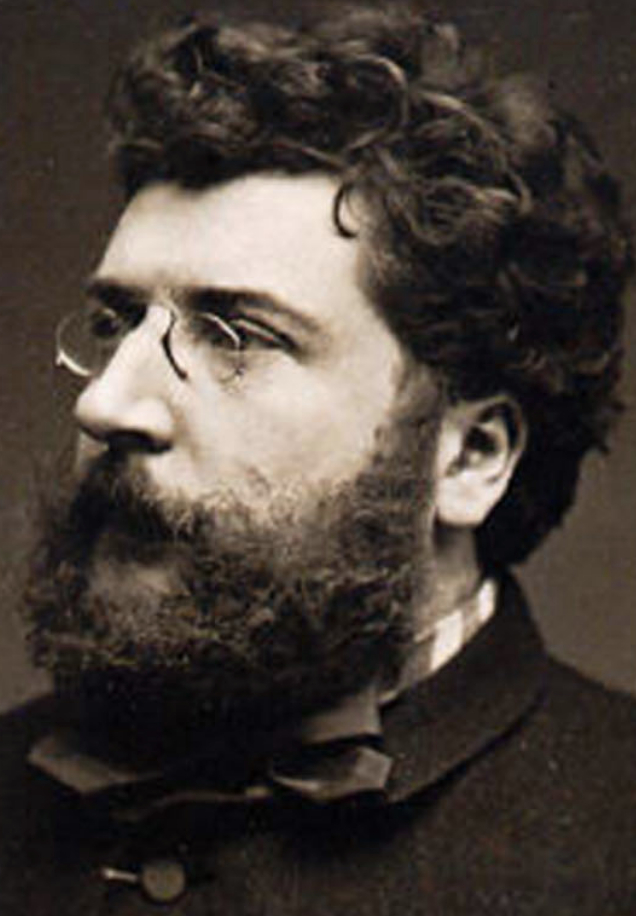

Georges Bizet

On this date in 1838, composer Georges Bizet (Alexandre César Léopold Bizet) was born in Paris. The musical prodigy entered the Paris Conservatoire at age 9. Over the next decade he won virtually every prize available, including the Prix de Rome. Bizet refused a career as a concert pianist in order to compose operas. He wrote about 30, none particularly successful, until he composed “Carmen” in 1875, based on Prosper Merimee‘s novella about a Spanish gypsy girl.

“Carmen” was controversial not only because of its humble subject matter and passionate sweep, but for the fact that the libretto was written in French and (scandalously) could be understood by the audience. Criticism and a lukewarm reception closed the play after a brief run, although the composers of Bizet’s day praised it. The dejected composer, who suffered from ill health, died of a heart attack three months later at the age of 36, never knowing “Carmen” would become the most-produced opera in history. Bizet also wrote “Jeux d’Enfants,” 12 charming piano duets.

Bizet was a rationalist. As a young man, struggling with his religious and philosophical views, he was asked to write a Mass. Preferring to write a comedy, he replied: “I don’t want to write a mass before being in a state to do it well, that is [as] a Christian. I have therefore taken a singular course to reconcile my ideas with the exigencies of Academy rules. They ask me for something religious: very well, I shall do something religious, but of the pagan religion.” (Georges Bizet: His Life and Work by Winton Dean, 1965.)

In 1869 he married Geneviève Halévy, the nervously unstable daughter of composer Fromental Halévy. Her family initially opposed the match with a “penniless, left-wing, anti-religious Bohemian.” (The Life and Times of the Great Composers by Michael Steen, 2003.) The marriage was intermittently happy and produced a son, Jacques. Bizet had fathered another son in 1862 with Marie Reiter, his father Adolphe’s housekeeper. The boy was brought up as Adolphe’s son; only on her deathbed in 1913 did Reiter reveal his true paternity.

A heavy smoker, he died at age 36 of a heart attack on his wedding anniversary on June 3, 1875.

Photo: Bizet in the year he died.

“Religion is a means of exploitation employed by the strong against the weak; religion is a cloak of ambition, injustice and vice.”

— Bizet, from "Bizet" by William Dean (1962)

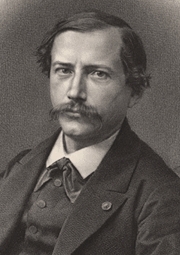

Marcellin Berthelot

On this date (some sources give Oct. 29) in 1827, Pierre Eugène Marcellin Berthelot was born in Paris, the son of a doctor. Educated at Lycée Henri-IV, Berthelot became professor of chemistry at the School of Pharmacy in 1859, where he completed his greatest work in 1860, the two-volume Chimie organique fondee sur la synthese (organic chemistry based on synthesis), the basis of modern organic chemistry.

Berthelot was one of the first to produce organic compounds synthetically. He argued and demonstrated that chemical phenomena are not governed by any peculiar law subject only to chemicals. The College de France created a chair of organic chemistry for him in 1865. He was admitted to the Academy of Sciences in 1873. He received the Legion of Honor in 1886 and was made perpetual secretary of the Academy of Sciences in 1889, succeeding Louis Pasteur.

An honorary associate of the Rationalist Press Association, “He would listen to no compromise whatever with religion,” wrote freethought historian Joseph McCabe, referring to Berthelot’s Science et Morale (1897) and Science et Libre Pensee (1905). He died soon after his wife Sophie and was buried with her in the Panthéon in 1907. They had six children.

“In a letter addressed to the Rome Congress of Freethinkers in 1904 [Berthelot] scorns ‘the poison vapours of superstition’ and longs for a ‘reign of reason.’ ”

— J.B. Wilson, quoting Berthelot in "A Trip to Rome" (1905)

Alexander Buchner

On this date in 1827, Alexander Karl Ludwig Buchner, German writer and younger brother of Ludwig and Georg Buchner, was born in Darmstadt, Germany. He was educated at Zurich University and taught philosophy there for a time. In 1862 he became a professor of German literature and language at Caen University in France.

He wrote extensively on English poetry and published “History of English Poetry” as well as works on Shakespeare, Byron, Thomas Chatterton and Richard Wagner. He was forced into exile in Holland in 1849 for his political views. He alluded to his own rationalist views in his exuberant support of his brother Ludwig’s scientific work. D. 1904.

“Before [his brother Ludwig’s book] “Force and Matter” what did the world at large know then of the first achievements of science? The vast majority were sunk in their blind faith in authority and the Bible.”

— Buchner, praising his brother's scientific achievement, introduction to "Last Words on Materialism and Kindred Subjects" by Ludwig Buchner (1901)

Max Stirner

On this date in 1806, Johann Kaspar Schmidt (known by his pseudonym Max Stirner), was born in Bayreuth, Bavaria. He entered the University of Berlin in 1826, the University of Erlangen in 1828 and then the University of Königsberg in Prussia, where he completed an undergraduate degree. He worked as a teacher of history and literature from 1839-44. Stirner quit his job after writing his philosophical book The Ego and Its Own (1844). He was an anarchist, nihilist and egoist and his views were reflected in The Ego and Its Own. Stirner married Agnes Butz, who died in childbirth in 1838. He later married Marie Dähnhardt.

Born to a Lutheran family, Stirner became critical of religion. In The Ego and Its Own, he wrote, “We are perfect altogether, and on the whole earth there is not one man who is a sinner! There are crazy people who imagine that they are God the Father, God the Son, or the man in the moon, and so too the world swarms with fools who seem to themselves to be sinners; but, as the former are not the man in the moon, so the latter are not sinners. Their sin is imaginary.”

In June 1842 he published an article titled “Art and Religion” in the Rheinische Zeitung, in which he strongly critiqued the religious: “The religious spirit is not inspired. Inspired piety is as great an inanity as inspired linen-weaving. Religion is always accessible to the impotent, and every uncreative dolt can and will always have religion, for uncreativeness does not impede his life of dependency.” He died in Berlin at age 49 about a month after being stung in the neck by an insect and falling into a “nervous fever.” No photos of him are known to exist. The accompanying drawing of him, c. 1892, is by the philosopher Friedrich Engels. (D. 1856)

“Religion itself is without genius. There is no religious genius, and no one would be permitted to distinguish between the talented and the untalented in religion.”

— Stirner article "Art and Religion," Rheinische Zeitung (June 1842)

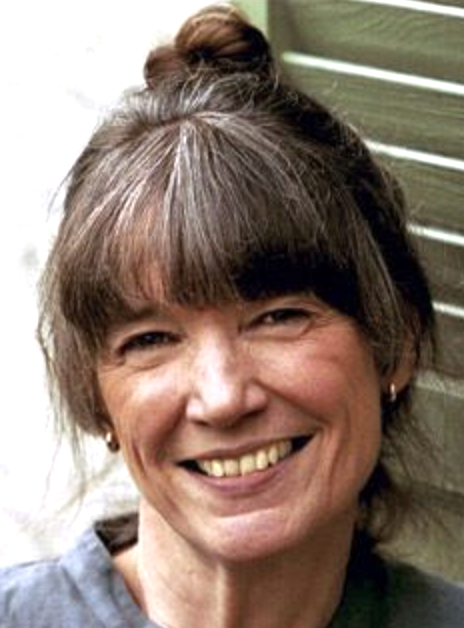

Anne Tyler

On this date in 1941, American novelist and critic Anne Tyler was born in Minneapolis. Both parents were Quakers and social activists. The family lived in a Quaker commune in North Carolina while Tyler was young. After graduating from high school at age 16, she enrolled at Duke University on a full scholarship. She majored in Russian literature and was involved in Duke’s drama society and the visual arts and graduated in 1961. She received a fellowship from Columbia University in Slavic studies but left graduate school after a year.

Tyler has published 22 novels as of this writing in 2019. The best-known are “Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant”(1982), “The Accidental Tourist” (1985) and “Breathing Lessons” (1988). All three were finalists for the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, with “Breathing Lessons” winning the prize in 1989.

Tyler has worked as a literary critic and journalist and has written short stories, many published in The New Yorker, the Saturday Evening Post, Redbook, McCall’s and Harper’s. Her work escapes classification, although she is often labeled a “Southern author” or a “modern American author.” Tyler’s works are known for their depictions of family life and their intensely real characters and detailed descriptions.

She married Iranian psychiatrist and novelist Taghi Mohammad Modarressi in 1963. Living in Baltimore, they raised two daughters, Tezh and Mitra. Modarressi, 10 years Tyler’s senior, died of lymphoma in 1997 at the age of 65.

“I remember when I was 7, making crucial decisions about the kind of person I was going to be. That’s also the age when I figured out that, oh, someday I’m going to die, and the age when I decided I couldn’t believe in God.”

— Anne Tyler, The New York Times (July 6, 2018)

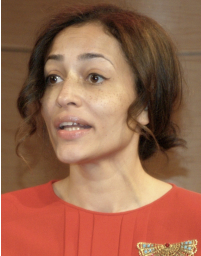

Zadie Smith

On this date in 1975, author and essayist Zadie Smith was born in the London suburb of Willesden to Yvonne (Bailey) and Harvey Smith. Her mother, a Jamaican immigrant, was 30 years younger than her English father. Born Sadie, she changed her name to Zadie at age 14 to make it “zippier.” Her parents divorced when she was a teen.

She graduated from King’s College-Cambridge, where she studied English literature and auditioned unsuccessfully for the Footlights sketch comedy troupe. Her first novel “White Teeth” was completed at age 24 in her final year at Cambridge and published in 2000. She’d received an unheard of advance of $400,000 for a 19-year-old after submitting fewer than 100 pages. In a dust jacket blurb, Salman Rushdie called it an “astonishingly assured debut.” (New York Times, April 30, 2000)

Several well-regarded novels followed: “The Autograph Man” (2002), “On Beauty” (2005), “NW” (2012), “Swing Time” (2016) and “The Fraud” (2023). She also published the novella “The Embassy of Cambodia,” several collections of essays and short stories and a play, “The Wife of Willesden,” adapted from Chaucer.

An interviewer in 2016 noted Smith had “delved deep into Judaism, Islam and more” in her books and asked if she had a faith: “No, I’m the absolute opposite. My mother was absolutely atheistic, she was brought up in the [Jehovah] Witnesses, in Jamaica, she had a very hard time. I make it funny in ‘White Teeth,’ but it wasn’t funny. It was real hellfire stuff.” Her mother later embraced Rastafarianism. (Financial Times, Nov. 11, 2016)

Smith met Nick Laird from Northern Ireland while they were Cambridge students. They married eight years later in 2004. He soon gained renown as a poet and novelist after giving up his law practice. They have a daughter Kit (b. 2009) and a son Harvey (b. 2013).

She took part in a squabble in the media brought on by journalist Lauren Sandler’s contention that having more than one child hurt women writers’ careers. Smith disagreed: “When I think of writers, I really love someone like Ursula Le Guin, who had three kids and lived an entirely domestic life. I feel her children in those books, I feel that the weight of it, her experience of being a girl, a woman, a mother, an old woman, it’s almost overwhelming when you read her.” (Slate, Nov. 16, 2016)

It seems clear from an anecdote Smith told that religion wasn’t pushed on her children. In the middle of the musical “There’s No Business Like Show Business,” which they were watching on TV, one of the characters leaves the family act to become a priest. “My daughter said, ‘What is a priest?’ ” remembered Smith.

Discussing her 2012 novel “NW” (a London postal code), Smith said that while writing it she rediscovered the “life-affirming” existentialists Camus and Sartre. “Camus is the least cynical man on Earth, the most positive, the most life-grabbing. He loved men, he loved women, he loved food, he loved Algeria, he loved France. He was nothing but love for existence, for what there was. … Nick always says this about me, and it’s true, [that] I have to do everything I can to not be a Christian. I have to put all my energy into not being religious. It’s a daily effort.” (Interview magazine, Aug. 24, 2012)

She and Laird have collaborated on a children’s book, and her journalism runs the gamut from film reviews to opinion pieces and cultural criticism. Humor is a frequent component and “finds full expression when Smith considers Justin Bieber in relation to the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber. ‘Meet Justin Bieber!’ is a very funny essay but it is also, and this is the quiet miracle of it, wholly intellectually sound.” (The New Republic, Feb. 20, 2018)

PHOTO: Smith in 2011; David Shankbone photo under CC 3.0.

“That goodness does exist, that’s my god, it’s enough.”

— Interview, Financial Times (Nov. 11, 2016)