May 23

Margaret Fuller

On this date in 1810, Margaret Fuller was born in Massachusetts, the first of nine children. Fuller became one of the foremost 19th-century women writers and critics. When her father died in 1835, she assumed financial headship of the family, teaching at Bronson Alcott’s Temple School. She translated Goethe and became editor of the Transcendentalist publication The Dial for two years under Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Her first book, Summer on the Lakes, was published in 1844, in which she observed the missionary harm to native Americans in the Midwest. At age 34, she became the first woman staff member of the New York Tribune, opening the doors of journalism to women and often writing of women’s needs.

Woman in the Nineteenth Century, in the vein of Mary Wollstonecraft‘s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, came out in 1845: “Women are, indeed, the easy victims both of priestcraft and self-delusion; but this would not be, if the intellect was developed in proportion to the other powers.” As a foreign correspondent for Horace Greeley, Fuller traveled to Europe, where she befriended Italian republican revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini.

Living in Rome, she met a handsome younger nobleman. They married secretly and had a son in 1848. When the republican cause was lost, they sailed to America, and were tragically drowned in a shipwreck on July 19, 1850, 50 yards from shore.

Her Memoirs, published posthumously, was bowdlerized by the Unitarian minister William Henry Channing, who put them together, according to biographer Bell Gale Chevigny. Chevigny documented pious salutations, such as “O Father,” inserted into Fuller’s words to soften irreverencies. Chevigny’s book, The Woman and the Myth, Margaret Fuller’s Life and Writings, restores Fuller’s original words. A possible Deist at most, Fuller wrote in 1842: “You see how wide the gulf that separates me from the Christian Church.” (D. 1850)

"Give me truth; cheat me by no illusion."

— Fuller, credo from "Memoirs," posthumously published in 1852 by Ralph Waldo Emerson, W.H. Channing and J.F. Clarke

Pär Lagerkvist

On this day in 1891, Pär Fabian Lagerkvist, who became a Nobel laureate, was born in Växjö, Småland, a rural province in southern Sweden. After a year of study at the University of Uppsala, Lagerkvist traveled to Paris in 1912, where he immersed himself in the modern art movement, which ultimately influenced his early writings. He abandoned realism and instead followed the surreal, symbolic example of the playwright August Strindberg.

Lagerkvist described himself as “a believer without faith — a religious atheist.” (Contemporary Authors Online) Much of his work was concerned with religious themes, such as the conflict between Christianity and technology, the meaning of life and the relationship between individuals and God.

Several of his later works, such as the novels Barabbas (1950) and Herod and Mariamne (1967) deal with biblical characters and settings in a fictional context. Others deal with religious mythology, such as 1960’s The Death of Ahasuerus, about the Christian mythological figure commonly known as the “Wandering Jew.” Many critics have said that Lagerkvist’s characters, like himself, are doubters who want to believe but lack faith.

In 1951 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Lagerkvist did not answer questions about his personal life and discouraged the production of biographies during his lifetime. His second wife, Elaine Sandel, died in 1967. They had three children, Ulf, Bengt and Elin. He died at age 83 in Stockholm. (D. 1974)

"If you believe in god and no god exists

then your belief is an even greater wonder.

Then it is really something inconceivably great.Why should a being lie down there in the darkness crying to someone who does not exist?

Why should that be?

There is no one who hears when someone cries in the darkness. But why does that cry exist?"— Lagerkvist, "Aftonland," translated by W. H. Auden and Leif Sjöberg in "Evening Land" (1975)

Joan Collins

On this date in 1933, actress and writer Joan Henrietta Collins was born in London to Elsa (Bessant) and Joseph Collins, respectively a British dance teacher/nightclub hostess and a talent agent from South Africa. After debuting on the stage at age 9 in Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House,” she trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art.

Her movie debut was as a beauty contest entrant in “Lady Godiva Rides Again” (1951), followed by significant roles in other films, including a 1953 top billing in “Our Girl Friday.” After moving to Hollywood at age 22, her performance in “Land of the Pharaohs” (1955) led to a contract with 20th Century Fox and roles in several successful films in the ’50s and early ’60s, when she started appearing in television productions.

After returning to Britain to act and later going back to Hollywood, Collins’ portrayal of Alexis Carrington on the ABC-TV series “Dynasty” from 1981-89 led to a Golden Globe in 1982 and a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame the next year. It was the most-watched show in 1984-85. She continued to appear in films, on the stage and on TV into the 2000s. She also became a successful writer of fiction and nonfiction books. (Her sister was the late romance novelist Jackie Collins.)

A political conservative, she became a regular columnist with The Spectator, a British weekly, in the late ’90s and contributed to numerous other U.S. and British publications. She was named a dame, the female equivalent of a knight, by Queen Elizabeth II in 2015 for her charitable works. Collins has married five times, most recently to Percy Gibson in 2002. He’s 31 years younger. Collins has three children.

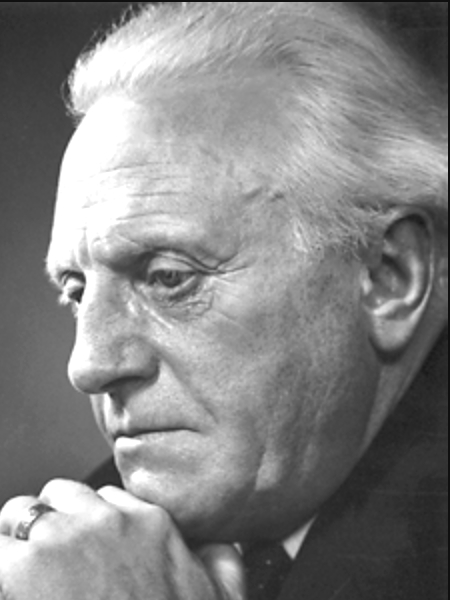

PHOTO: Collins in 1956 during filming of “The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing.”

“I'm not a religious person, nor am I an atheist. I'm more of an agnostic, really. But I was raised with Christian values by a Church of England mother to the amusement of my Jewish father and my 'hovering Buddhist' uncle George, who'd been in a Japanese concentration camp. I was told that I could choose my own religious beliefs 'when I grew up.' "

— Collins' column in The Spectator magazine (Dec. 12, 2015)