December 7

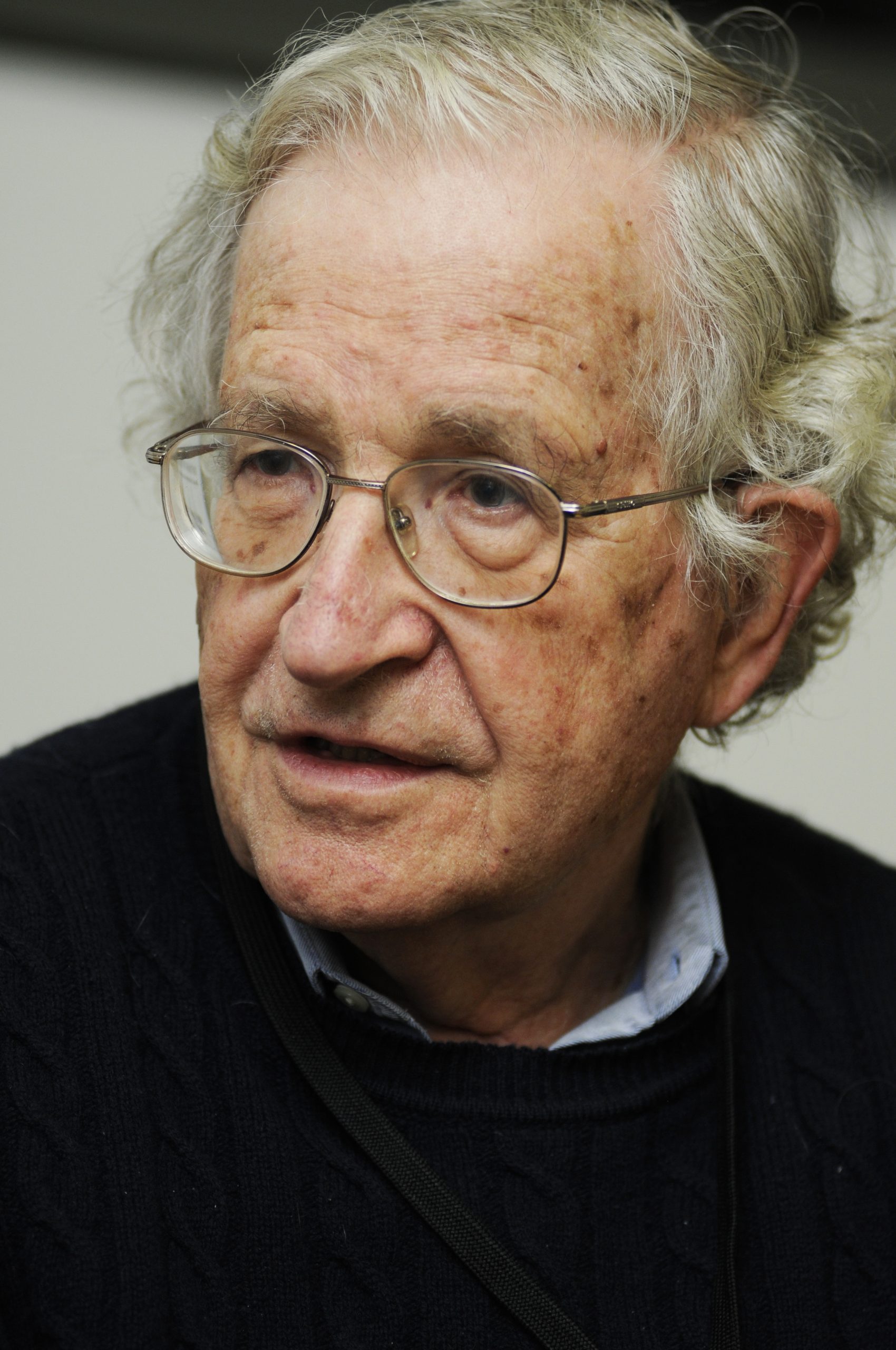

Noam Chomsky

On this date in 1928, Avram Noam Chomsky, the son of a Ukrainian immigrant Hebrew scholar, was born in Philadelphia. Although Chomsky would revolutionize the world of linguistics, politics has been close to his heart since childhood and has brought him even greater renown (and controversy). From an early age, Chomsky attended a day school that based its curriculum on the theories of John Dewey. As a teen he frequented New York City bookstores and places where Jewish intellectual men gathered. He received his B.A. (1949), M.A. (1951) and Ph.D. (1955) from the University of Pennsylvania.

He grew disenchanted as a Penn student with the structure of formal education and considered moving to a kibbutz in Palestine to promote Arab-Jewish cooperation. Then his interest in linguistics grew under the mentorship of Zellig Harris, founder of the first department of linguistics in the country, who convinced him to major in that field. Chomsky was Harris’ student from the undergraduate level, starting in 1946, through the doctoral level.

He married Carol Doris Schatz in 1949, a linguist he had known since childhood. In 1951 he was inducted into the Society of Fellows on a four-year term at Harvard University. Chomsky joined the faculty at MIT in 1955, working there in different research and academic positions for the next 60 years.

In 1957 he wrote Syntactic Structures, which revolutionized the field of linguistics and put Chomsky on the academic map. Prior to that book, most social scientists believed language and other human behaviors were learned through observation instead of being generated through more complex and innate processes.

In the 1960s Chomsky became one of the earliest and most outspoken critics of the Vietnam War. In 1967 he spent the night in jail for his involvement in the organization of a Vietnam War protest march at the Pentagon. His 1969 book, American Power and the New Mandarins, landed him on President Richard Nixon’s “enemies” list. In 1971, in Cambridge, England, Chomsky gave the Bertrand Russell Memorial Lectures, which were published as Problems of Freedom and Knowledge (1971). He has had numerous books, lectures, interviews and articles published, many of which are critical of U.S.-led atrocities in Vietnam, South and Central America, Laos and Cambodia.

His controversial book Counter-Revolutionary Violence: Bloodbaths in Fact and Propaganda (1973), co-authored with Edward S. Herman, was censored and ordered to be destroyed by its publisher, Warren Communications, because the book accused the U.S. of violence against native peoples. He continued to write monumental works on linguistics and politics, including Rules and Representations (1980), The Political Economy of Human Rights (1979), Terrorizing the Neighborhood: American Foreign Policy in the Post-Cold War Era (1991) and Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (1988), co-authored with Herman.

More recently he published Occupy (2012), a short history of the Occupy movement, Failed States: The Abuse of Power and the Assault on Democracy (2006), Gaza in Crisis (2010) and Requiem for the American Dream (2017). After his wife died in 2008, he married Valeria Wasserman in 2014. He has three children.

"I am a child of the Enlightenment. I think irrational belief is a dangerous phenomenon, and I try to consciously avoid irrational belief."

— Chomsky, interview with David Barsamian in "Chronicles of Dissent" (1992)

Heywood C. Broun

On this date in 1888, journalist Heywood Campbell Broun Jr. was born in Brooklyn, N.Y. He attended Harvard University from 1906-10, where he befriended Walter Lippmann and John Reed. Broun left Harvard 10 credits short of a degree to become a sportswriter for the New York Morning Telegraph. He joined the New York Tribune and covered World War II as its correspondent in France. In 1921 he joined the New York World and debuted his column “It Seems to Me.”

He married feminist writer Ruth Hale in 1917, who a few years later co-founded the Lucy Stone League that advocated letting women keep their maiden names after marriage. They had one son, sportswriter Heywood Hale Broun. After Hale filed for divorce in 1933, he married a widowed chorus girl named Maria Incoronata Fruscella Dooley (stage name Connie Madison) in 1935.

Broun campaigned for the underdog, against censorship and racism and for women’s rights. He supported Eugene V. Debs, Margaret Sanger, D.H. Lawrence and Tom Mooney, a labor leader he believed was framed in a 1916 San Francisco bombing case. Broun resigned when the World refused to run his coverage of the Sacco and Vanzetti case. In 1930 he ran unsuccessfully as a Socialist for Congress. Several years later, the Socialists expelled him for appearing on the platform with members of the Communist Party in support of Mooney and the Scottsboro Nine.

He wrote for The Nation and the New Republic and helped establish the American Newspaper Guild in 1933, which still gives out the Heywood Broun Award for news organizations showing an abiding concern for the underdog. In 1938 he co-founded the weekly tabloid Connecticut Nutmeg, soon renamed Broun’s Nutmeg.

Broun, one of the wits of the Algonquin Round Table, was said to have whispered to Tallulah Bankhead during a Broadway show in which she was starring: “Don’t look now, Tallulah, but your show’s slipping.” He wrote several books and novels, including The A.E.F. (1918), The Boy Grew Older (1922) and a biography, Anthony Comstock: Roundsman of the Lord (1927, with Margaret Leech). Christians Only: A Study in Prejudice (1931, with George Britt), showed how all-encompassing anti-Semitism was in the 1920s, with some Jews even discriminating against other Jews.

Broun played it close to the vest when publicly discussing or writing about his own religious beliefs, but among contemporaries he was widely seen as agnostic. He generally opposed stridency, even from what he called “hard-shelled” atheists: “Nobody talks so constantly about God as those who insist that there is no God.” (“A New Preface to an Old Story,” Broun’s Nutmeg, Aug. 19, 1939)

Near the end of his life, influenced by Bishop Fulton J. Sheen, he converted to Catholicism, although the sincerity of his conversion was questioned by some. He died of pneumonia at age 51 in a hospital in Kingston, N.Y. (D. 1939)

” ‘Virtue is a polite word for fear,’ that is the sort of thing we were writing when we were not empowering some character to say, ‘Honesty is a bedtime fairy story invented for the proletariat,’ or ‘The prodigal gets drunk; the Puritan gets religion.’ "

— Broun, on his Harvard English class for playwrights, "Pieces of Hate and Other Enthusiasms" (1922)