cartoonists

Steve Benson

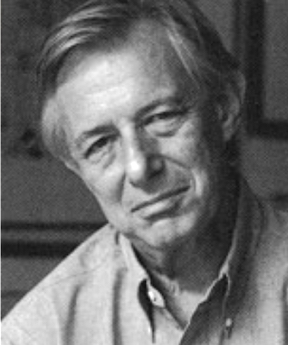

On this date in 1954, Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist Stephen Reed “Steve” Benson was born in Sacramento, Calif., the grandson of Ezra Taft Benson, who served as secretary of agriculture under President Dwight Eisenhower and became president of the Mormons (1985-94). Benson was an Eagle Scout and graduated with a degree in political science, cum laude, from Brigham Young University in 1979. “I was on track to eternal Mormon stardom, reserved especially for faithful men in a church run by men,” he has written.

He worked briefly as an editorial cartoonist for the Morning News Tribune in Tacoma, Wash., before starting a long association as a cartoonist with the Arizona Republic in 1980, where he won a Pulitzer Prize in 1993. He and his wife Mary Ann, who had four children, left the Mormon Church in a highly publicized break in 1993, “citing disagreement over its doctrines on race, women, intellectual freedom and fanciful storytelling,” as he has written.

Benson listed among the benefits of leaving religion: “Another day off, a 10-percent raise and getting to choose his own underwear.” Among his favorite sayings was Mark Twain’s adage “Get your facts first, and then you can distort them as much as you please.”

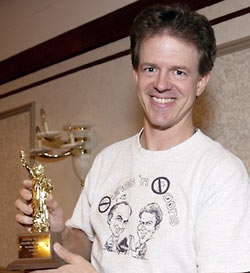

An atheist, he has appeared at several FFRF annual conventions. He received a Tell It Like It Is Award (1999), an Emperor Has No Clothes Award (2002) and a Friend of Freedom Award (2003). The inspiration for the Freedom Award, a statuette of liberty, came from Benson’s cartoon that year. In the cartoon, filmmaker Michael Moore was pictured at the Academy Awards, where he won an Oscar for “best documentary,” holding not an Oscar but a small replica of the Statue of Liberty.

For several years starting in 2001, Benson teamed up with FFRF Co-President Dan Barker for the inimitable “Tunes and ‘Toons” production, an irreverent look at freethought and religion in the news. Some of their jointly written parodies, “Godless America” among them, are recorded on the “Beware of Dogma” CD.

He started a new chapter in his life in 2020 when he married Claire Ferguson. He suffered a debilitating stroke in 2024 from which he never fully recovered and died at age 71. (D. 2025)

“If, as the true believers claim, the word ‘gospel’ means good news, then the good news for me is that there is no gospel, other than what I can define for myself, by observation and conscience. As a freethinking human being, I have come not to favor or fear religion, but to face and fight it as an impediment to civilized advancement."

— Benson, "From Latter-Day Saint to Latter Day Ain't" (Freethought Today, December 1999)

Jules Feiffer

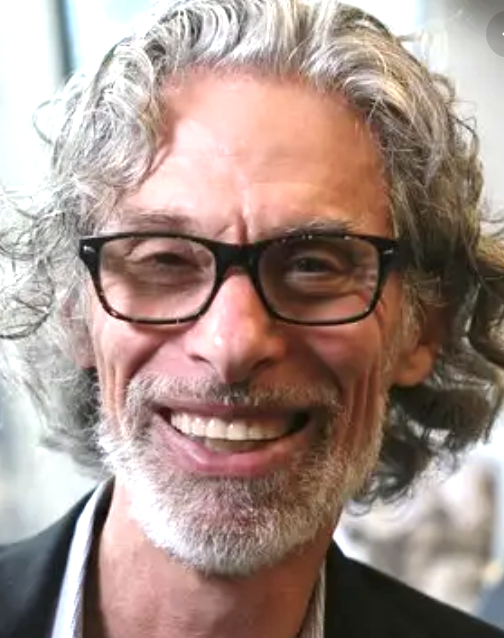

On this date in 1929, cartoonist, playwright and author Jules Ralph Feiffer was born in the Bronx, New York to David Feiffer, an unsuccessful men’s shop entrepreneur, and Rhoda (Davis) Feiffer, who sold dress designs and largely supported their family.

His weekly editorial cartoons appeared in the Village Voice for 42 years. Feiffer won the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning in 1986. His cartoons have been published in 19 books. He was named to the Comic Book Hall of Fame in 2004.

Feiffer’s anti-military animated cartoon “Munro” won an Academy Award in 1961. His comedy “Little Murders” (1967) won an Obie. Among his other plays and revues is “Knock Knock,” which had a 1976 Broadway run starring Lynn Redgrave. Feiffer wrote the screenplay for the film “Carnal Knowledge” (1971), which spawned censorship and lawsuits.

Feiffer was married three times and had three children. His daughter Halley Feiffer is an actress and playwright. In 2016 he married freelance writer Joan “JZ” Holden. The ceremony combined Jewish and Buddhist traditions. She is the author of Illusion of Memory (2013).

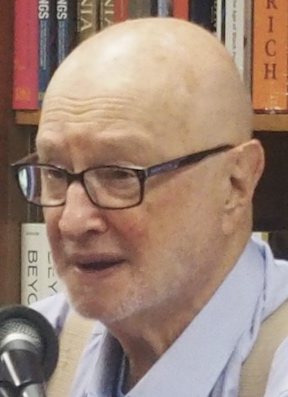

He died of congestive heart failure nine days before his 96th birthday at his home in Richfield Springs, N.Y. (D. 2025)

PHOTO: Feiffer reading at Politics and Prose in 2018 in Washington, D.C. Photo by SLOWKING under CC BY-NC.

"Christ died for our sins. Dare we make his martyrdom meaningless by not committing them?"

— Lines from Feiffer's play "Little Murders," first performed on and off Broadway in the late 1960s

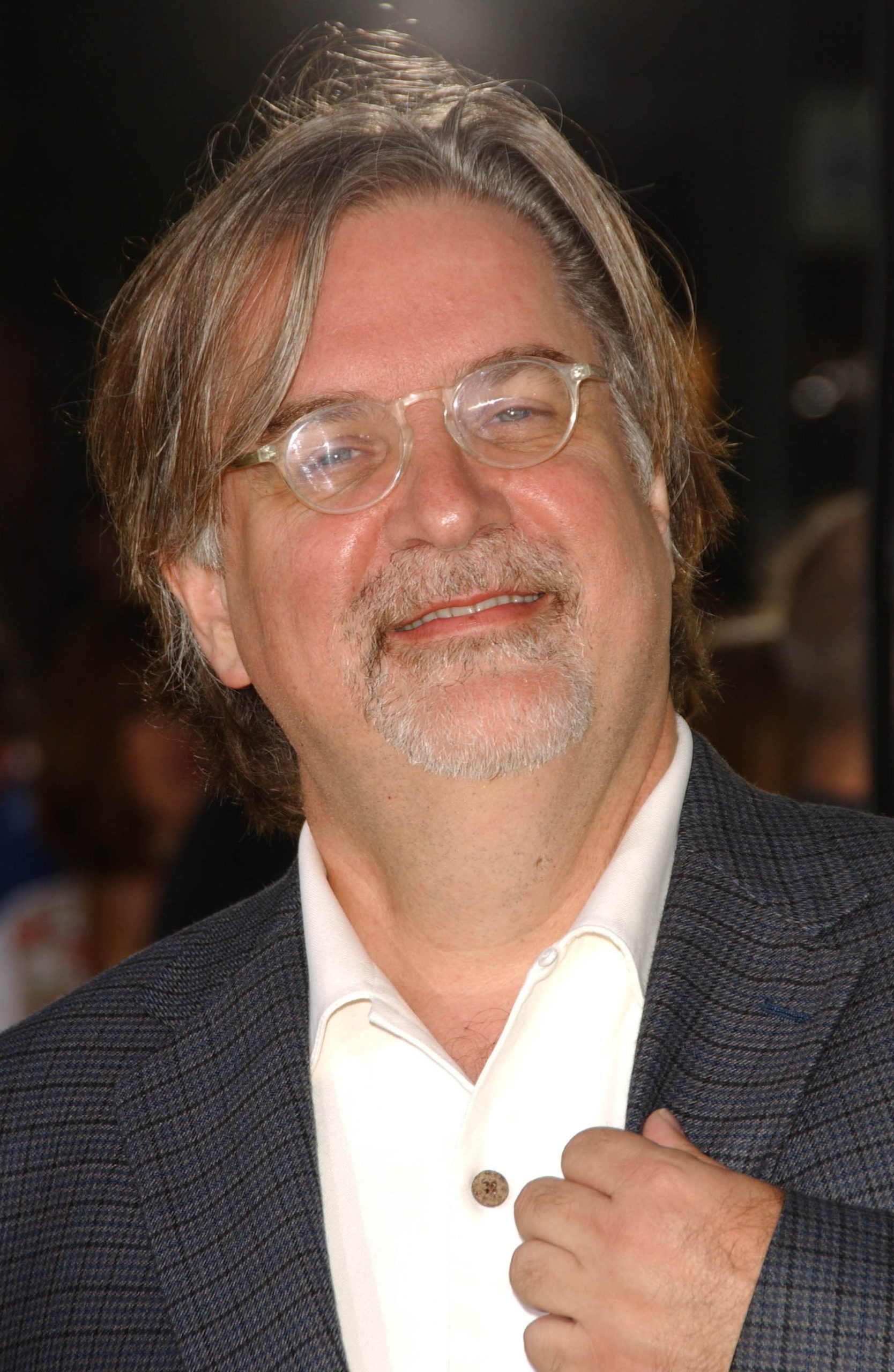

Matt Groening

On this date in 1954, Matthew Abraham Groening was born in Portland, Ore., to Homer Groening, an advertising agent and amateur cartoonist, and Margaret Wiggum. Groening was one of four children. Best known as the creator and executive producer of the TV program “The Simpsons,” Groening’s career started when he moved to Los Angeles after graduating from Evergreen State College and began selling Xeroxed copies of his comic strip “Life in Hell,” an irreverent look at a broken life. This original strip was subsequently syndicated, became successful and eventually caught the attention in 1987 of James L. Brooks, executive producer of “The Tracey Ullman Show.”

Looking for a “filler” in the show, Brooks asked Groening to create animated TV “shorts” which became “The Simpsons,” the longest-running animated series in TV history. Groening later created another successful animated TV show, the fantasy-based “Futurama.” In 1993 he formed and became publisher of the “Bongo Comic Group,” overseeing the “Simpsons Comics,” “Itchy & Scratchy Comics,” “Bartman,” “Radioactive Man,” “Lisa Comics” and “Krusty Comics.”

In an IMDB.com mini biography by Kevin Newcombe, Groening is quoted as saying: “Cartooning is for people who can’t quite draw and can’t quite write. You combine the two half-talents and come up with a career.” He produced the adult animated fantasy sitcom “Disenchantment” for Netflix in 2018. Twenty more episodes were scheduled to air between 2020 and 2021.

Groening and Deborah Caplan married in 1986 and had two sons, Homer (who goes by Will) and Abe. They divorced in 1999 and Groening married Argentine artist Agustina Picasso in 2011. They have a son, Nathaniel, and twin daughters, Luna and India.

“Technically, I’m an agnostic, but I definitely believe in hell — especially after watching the fall TV schedule.”

— New York Times interview (Dec. 17, 1998)

Edward Sorel

On this date in 1929, illustrator, artist and satirist Edward Sorel was born in Bronx, N.Y., to Morris and Rebecca (Kleinberg) Schwartz. He packs a lot of punch with few, and very often, no words. Look at Sorel’s “Pass the Lord and Praise the Ammunition” from 1967, for example. The color halftone poster, on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery, depicts New York Cardinal Francis Spellman in clerical garb and Army boots on the advance, wielding a rifle with fixed bayonet.

The conservative Catholic cardinal had been military vicar general of the U.S. armed forces since 1939 and was an outspoken hawk on the Vietnam War. By 1967 he was out of step with many Americans. Just as Sorel was finishing the poster, Spellman died, so he waited till 1972 to use the image for the cover art of his book “Making the World Safe for Hypocrisy.”

Sorel is a regular contributor to The Atlantic and The New Yorker and many other publications. Besides his 41 covers for the latter, his art has appeared on the covers of The Atlantic, Harpers, Fortune, Forbes, The Nation, Esquire, American Heritage and The New York Times Magazine. He has illustrated many children’s books, three of which he also wrote. “Unauthorized Portraits,” a collection of his works, was published by Knopf in 1997.

He is a recipient of the Augustus St. Gaudens Medal for Professional Achievement from The Cooper Union, the Hamilton King Award from The Society of Illustrators, the Page One Award from the Newspaper Guild, the Best in Illustration Award from the National Cartoonists Society, the George Polk Award for Satiric Drawing and the “Karikaturpreis der deutschen Anwaltschaft” from the Wilhelm Busch Museum in Hanover, Germany. In 2001 the Art Directors Club of New York elected him to its Hall of Fame.

Sorel graduated from the Cooper Union in 1951 and co-founded Push Pin Studios with Milton Glaser and Seymour Chwast in 1953 before embarking on a very successful freelance career. In a 1997 interview, he was asked what issues he felt especially strong about and was inspired to address. He answered, “I’m one of those who regard organized religion as a dangerous force. I try whenever possible to do anti-clerical cartoons. The only place that will print them is The Nation, which has a very small circulation and pays almost nothing.” (The Atlantic, Nov. 6, 1997)

Sorel, sitting for a joint interview with fellow artists Jules Feiffer and David Levine in 2003, was asked about earlier saying he hated the Bush administration and Saddam Hussein. “All I said was that we have our religious fanatics fighting their religious fanatics, which leaves me without a side to root for,” he replied.

In 1998 the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., devoted several rooms to an exhibition of his caricatures. The introduction to the “Unauthorized Portraits” exhibit said Sorel’s “potent spoofs of public figures … skewered pomposity wherever it appeared or simply mused on the exquisite oddness of the human comedy.”

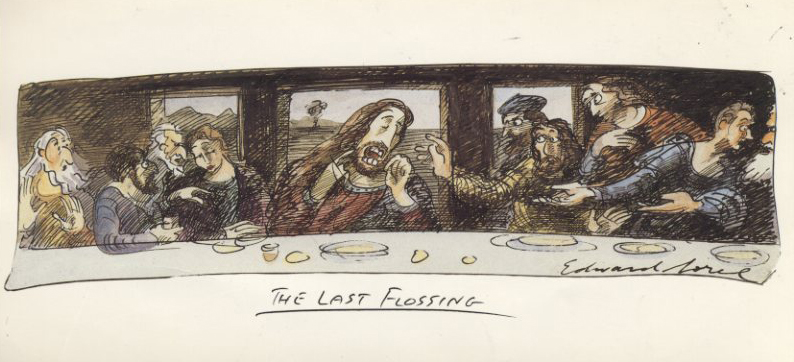

The exhibit had three sections — history, entertainment and the arts and politics: “From Moses leading his kvetching people (‘Some miracle! If I don’t get pneumonia, that’ll be a miracle’) through the parted Red Sea waters, to George Gershwin teaching Fred Astaire a dance step, to Madonna seen as a ‘horseperson of the apocalypse.’ ” Below, he reimagines da Vinci’s “The Last Supper.”

Sorel’s “The Last Flossing” (1992)

—

Bob Mankoff

On this date in 1944, Robert “Bob” Mankoff, cartoonist, writer and humor enthusiast, was born in New York City. Mankoff grew up in the borough of Queens in a Jewish family. Mankoff graduated from Syracuse University in 1966. He then attended Queens College to pursue a doctorate degree in experimental psychology, but found that his passion was humor.

For two years he submitted around 500 cartoons to The New Yorker without success. After his first submission was published 40 years ago, more than 900 of his cartoons have appeared in The New Yorker. He began The Cartoon Bank in 1991, a database of rejected New Yorker cartoons, which licenses cartoons to use in various media such as textbooks, magazines and newsletters.

The New Yorker purchased the bank in 1997, when he was named New Yorker cartoon editor, where he stayed for 20 years until stepping down in 2017. In 2018 he launched CartoonCollections.com as an archive and online store featuring the cartoons of over 70 illustrators.

Mankoff is credited with creating one of the most reprinted cartoons in The New Yorker’s history. It depicts a businessman at his desk talking on the phone while reviewing his calendar, saying, “No, Thursday’s out. How about never. Is never good for you?” He occasionally pokes fun at religion. In one scene, a man standing in a crowded church entrance says, “Good sermon, Reverend, but all that God stuff was pretty far-fetched.” In another, an obviously Jewish cleric says on the phone, “And remember, if you need anything I’m available 24/6.”

Mankoff has written several books, including his memoir How About Never: Is Never Good For You? My Life in Cartoons (2014) and The Naked Cartoonist: A New Way To Enhance Your Creativity (2002). He edited The Complete Cartoons of the New Yorker (2004) and several other New Yorker collections. He edited The New Yorker Encyclopedia of Cartoons: A Semi-serious A-to-Z Archive in 2018.

Mankoff has taught courses on the science and sociology of humor. He has partnered with the University of Michigan to conduct a series of experiments to study the role of humor in areas of economics, psychology and sociology.

After two prior marriages, Mankoff married Cory Scott Whittier in 1991. They live in New York and have a daughter, Sarah.

“Just to clear up any ambiguity, I'm not a believer, or even agnostic, I'm an atheist (denomination: Jewish). That means the God I don't believe in is different from the God you don't believe in if, for example, you're a Muslim atheist, a Catholic atheist, or a Protestant atheist."

— Mankoff column, "The cosmology of cartoonists," The New Yorker (May 1, 2013)

Jack Ziegler

On this date in 1942, satirist and cartoonist Jack Ziegler was born in Brooklyn, N.Y. He grew up in Forest Hills, Queens, in a Catholic household. His mother was a homemaker and his father sold pigment for a paint company. Ziegler developed an interest in cartoons at a young age, buying used comics on outings to Times Square. After graduating from Fordham University with a degree in communication arts, Ziegler joined the Army Reserve in Monterey, Calif.

While working at CBS network transmission facility, he started selling cartoons to various publications. The first cartoon he sold to The New Yorker was an illustration of Edgar Allan Poe contemplating which animal should say “Nevermore” — a turtle, moose or pig. His cartoons began appearing regularly in The New Yorker in 1974 and he was widely credited with bringing new life to the magazine.

Former cartoon editor Bob Mankoff described his drawings as “the platonic ideal of what a cartoon should look like.” During his lifetime he produced over 24,000 cartoons and sold over 3,000.

Ziegler also published several anthologies of drawings, including Hamburger Madness, How’s the Squid?: A Book of Food Cartoons; Olive or Twist?: A Book of Drinking Cartoons; and You Had Me at Bow Wow: A Book of Dog Cartoons. Most of his published work and personal papers are housed at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum at Ohio State University.

He married his first wife, Jean Ann, in 1969 and they had three children: Jessica, Benjaim and Maxwell. After divorcing, he married Kelli Gunter in 1996. He died at age 74 while living in Lawrence, Kansas. (D. 2017)

"Agnostic, I suppose, but it's not something I ever think about. Raised Catholic, but stopped at age thirteen, when I realized what a load it was. Don't like any religions at this point — think they're all nuts to one degree or another. And they cause way too much trouble in the world — as they always have.

— Ziegler, quoted in "The cosmology of cartoonists" by Bob Mankoff, The New Yorker (May 1, 2013)

Don Addis

On this day in 1935, Donald Gordon Addis was born in Hollywood, Calif., on a Friday the 13th. He grew up in (where else) Hollywood, Fla., and in 2004, after a long career as a freethinking editorial cartoonist and columnist with the St. Petersburg Times, he retired, on a (what else) Friday the 13th. Addis was an FFRF Lifetime Member and his cartoons have long been a treasured part of FFRF publications. Addis received the foundation’s Freethought in the Media “Tell It Like It Is” award at the 2005 national convention in Orlando.

Addis had a degree in design from the University of Florida, where he also edited the Orange Peel, then ranked as the nation’s No. 1 college humor magazine. He also served as editorial cartoonist on his college newspaper, The Alligator, as he did on his U.S. Army newspaper before that. He won 16 awards for cartooning from the Armed Forces Press Service. His work included the comic strips “Briny Deep” (1980), “The Great John L.” (1982–84), “Babyman” (1985) and “Bent Offerings” (1988–2004). He received the National Cartoonist Society Newspaper Panel Cartoon Award for 1992 for “Bent Offerings.”

He was awarded the National Cartoonists Society prize for Best Newspaper Panel Cartoon for 1993. He won the Florida Education Association School Bell Award for cartoons in the field of education four years in a row and several first places in the Florida Newspaper Illustrator and Cartoonists contest. He was named its Cartoonist of the Year. He also is recipient of the Ignatz Award (named for the Krazy Kat character) presented by his peers.

In his farewell column in the St. Petersburg Times, Addis said this to those who complained over the years that his work was not balanced or objective: “Objectivity is not my department. Balance is down the hall. Impartiality is another word for no reason to draw a cartoon.” He died at age 74 of lung cancer was survived by his wife Christi, three daughters and a son. His obituary in the Times gave a flavor of the man: “Though loyal to friends and family, Mr. Addis was not gregarious. While others partied though the holidays, he preferred to stay home with a book, where a welcome mat still reads ‘GO AWAY.’ He bought smelts for an egret in the neighborhood, which stalked him regularly.” (D. 2009)

“Do you have any weapons, flammable materials or hazardous religious beliefs?”

— Text with Addis cartoon showing a Native American checking a Mayflower pilgrim's suitcase

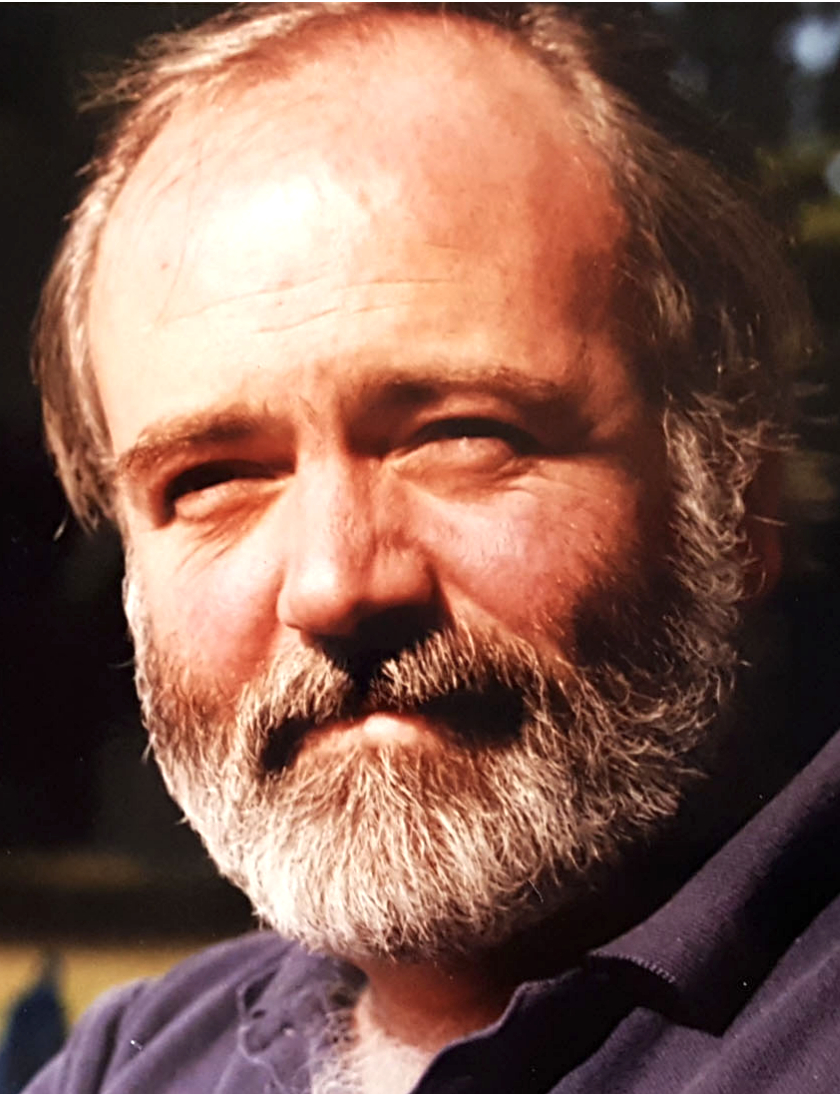

Charles Schulz

On this date in 1922, Charles Monroe Schulz was born in Minneapolis. After graduating from high school in St. Paul, he took a correspondence course from Art Instruction Schools Inc. He was drafted into the Army in 1943 and served as a staff sergeant in France and Germany until 1945. After the war he worked as an instructor for Art Instruction Schools and did freelance cartooning. Starting in 1947, he drew a comic strip, “Li’l Folks,” for the St. Paul Pioneer Press. In 1950, the United Feature Syndicate agreed to distribute the strip and renamed it “Peanuts.”

By 1953 “Peanuts” with its now-iconic lead character Charlie Brown was a hit. Over the years, Schulz received many awards and licensing deals for his work and wrote several “Peanuts” animated television specials. He had married Joyce Halverson in 1951 and they had five children before divorcing in 1972. In 1973 he married Jean Forsyth Clyde. In 1999 he was diagnosed with colon cancer and announced he was retiring, but that new strips would run daily until Jan. 3, 2000, and every Sunday until Feb. 13. He died in his sleep Feb. 12, 2000. His Chicago Tribune obituary noted he had once said that “The best theology is probably no theology; just love one another.”

Schulz was raised a Lutheran and as an adult served as a Methodist Sunday school teacher for ten years. In the 1980s and ’90s, however, he started to describe himself as a “secular humanist.” Schulz’s characters continued to quote the bible, discussing religion’s inconsistencies among their other philosophical musings.

Some readers have taken Schulz’s Halloween storyline of the character Linus’s persistent belief in the Great Pumpkin, expected to bring toys to the pumpkin patch but never showing up, as an allegory on religion. But Schulz did not claim any such thing and often said of “Peanuts” that he was just trying to write funny strips on time, not to expound any profound philosophical points. (D. 2000)

PHOTO: Library of Congress; Schulz in 1956.

“I do not go to church anymore, because I could not be an active part of things. I guess you might say I’ve come around to secular humanism, an obligation I believe all humans have to others and the world we live in.”

— Schulz, quoted in "Good Grief: The Story of Charles M. Schulz" by Rheta Grimsley Johnson (1989)

James Thurber

On this date in 1894, humorist and cartoonist James Grover Thurber was born in Columbus, Ohio. He called his mother — who once impersonated a cripple at a faith-healing rally in order to leap up and call herself cured — a “born comedienne.” Thurber was partially blinded as a young boy when his brother accidentally shot an arrow into his eye. He could not serve in World War I but attended Ohio State University from 1913-18. He was a code clerk in Washington, D.C., and at the U.S. Embassy in Paris, then became a newspaperman.

He wrote for the Chicago Tribune from Paris and joined the Evening Post staff in New York in 1927, then The New Yorker. He wrote a satire of psychoanalysis, Is Sex Necessary (1929) with E.B. White, featuring his drawings, which immediately became popular. Thurber’s eyesight worsened in the 1930s and 1940s. His books included My Life and Hard Times (1933), Fables for Our Time (“Early to rise and early to bed makes a male healthy and wealthy and dead”) and two modern fairy tales for children in the 1950s.

His most famous story was “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty,” about a meek husband with an absurdly rich inner fantasy life, which spawned a 1947 movie starring Danny Kaye. Thurber once said, “The wit makes fun of other persons; the satirist makes fun of the world; the humorist makes fun of himself, but in so doing, he identifies himself with people — that is, people everywhere, not for the purpose of taking them apart, but simply revealing their true nature.”

His biographer Harrison Kinney wrote, “Thurber had never allowed his probing, restless mind to settle on any single theological insurance policy concerning the possibilities of the hereafter. He remained an agnostic.” (Cited in Final Chapters: How Famous Authors Died by Jim Bernhard, 2015)

He was married to Althea Addams Thurber from 1925-35. Their daughter Rosemary was born in 1931. He was married to Helen Wismer Thurber from 1935 until his death at age 66 from pneumonia several weeks after being stricken with a cerebral blood clot. (D. 1961)

“If I have any beliefs about immortality, it is that certain dogs I have known will go to heaven, and very, very few persons.”

— Attributed to Thurber but unsourced