abolitionists

Lydia Maria Child

On this date in 1802, Lydia Maria Child (née Francis) was born in Medford, Mass. Considered one of the first U.S. “women of letters,” she became a famous abolitionist, author, novelist and journalist. Her poem “Over the River and Through the Wood” (originally titled “A Boy’s Thanksgiving Day”) became popular as a song: “Over the river and through the wood / to grandfather’s house we go.” After her mother died when she was 12, she went to live with her older married sister in Maine and studied to become a teacher.

She ran a private school, started the first journal for children and wrote several novels and popular how-to books such as The Frugal Housewife, The Mother’s Book and The Little Girl’s Own Book. Her history, The First Settlers of New England, blamed Calvinist-based racism for the treatment of Native Americans. She married David Childs, editor and publisher of the Massachusetts Journal, in 1828 when she was 26.

An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans recruited many to the anti-slavery movement, but made Child a pariah in Boston society. Her two-volume The History of the Condition of Women, in Various Ages and Nations was published in 1835. She continued abolition work, supporting herself through popular writings and newspaper columns. The Progress of Religious Ideas (1855) rejected theology, dogma, doctrines, and talked of “Providence” as the inward voice of conscience. Her funeral was presided over by Wendell Phillips, who said she was “ready to die for a principle and starve for an idea.” John Greenleaf Whittier recited a poem in her honor and The Truth Seeker memorialized her. D. 1880.

“It is impossible to exaggerate the evil work theology has done in the world.”

— Child, "The Progress of Religious Ideas Through Successive Ages" (1855)

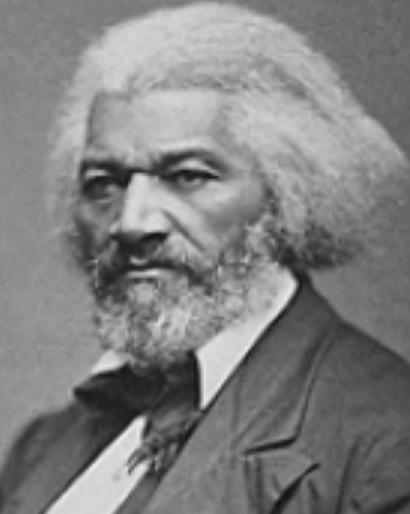

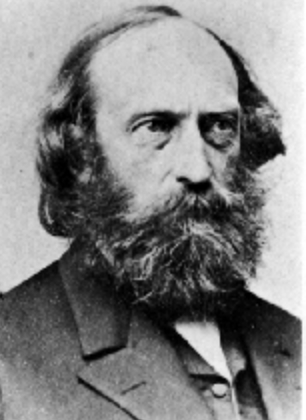

Frederick Douglass

This date is traditionally celebrated as the birthday of Frederick Douglass (né Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey). Born as a slave in Maryland in 1818, he was to become a renowned abolitionist, editor and feminist. Escaping from slavery at age 20, he renamed himself Frederick Douglass and became an abolition agent.

Douglass traveled widely, often at personal peril, to lecture against slavery. His first of three autobiographies, The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave, was published in 1845.

In 1847 he moved to Rochester, New York, and began publishing a weekly newspaper, North Star. Douglass was the only man to speak in favor of Elizabeth Cady Stanton‘s controversial plank of woman suffrage at the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848. As a signer of the Declaration of Sentiments, Douglass also promoted woman suffrage in North Star. Douglass and Stanton remained lifelong friends.

In 1870 Douglass launched The New National Era, published from 1870-74, in Washington, D.C. He was nominated for vice president by the Equal Rights Party to run with Victoria Woodhull as presidential candidate in 1872. He became U.S. marshal of the District of Columbia in 1877 and was later appointed minister resident and consul-general to Haiti. His District of Columbia home is a national historic site. (D. 1895)

* Editor’s note: Douglass was fairly religious, so the quote below may be interpreted, as it has by numerous religious writers, as prayer is very ineffective without action behind it. A skeptic might paraphrase it as nothing fails like prayer.

“I prayed that God would emancipate me, but it was not till I prayed with my legs that I was emancipated.”

— From Douglass' "Self-Made Men" lecture, perhaps his most popular and written in 1859. The New York Herald reported on the lecture delivered at the 16th St. Baptist Church in New York City. (Nov. 16, 1876)

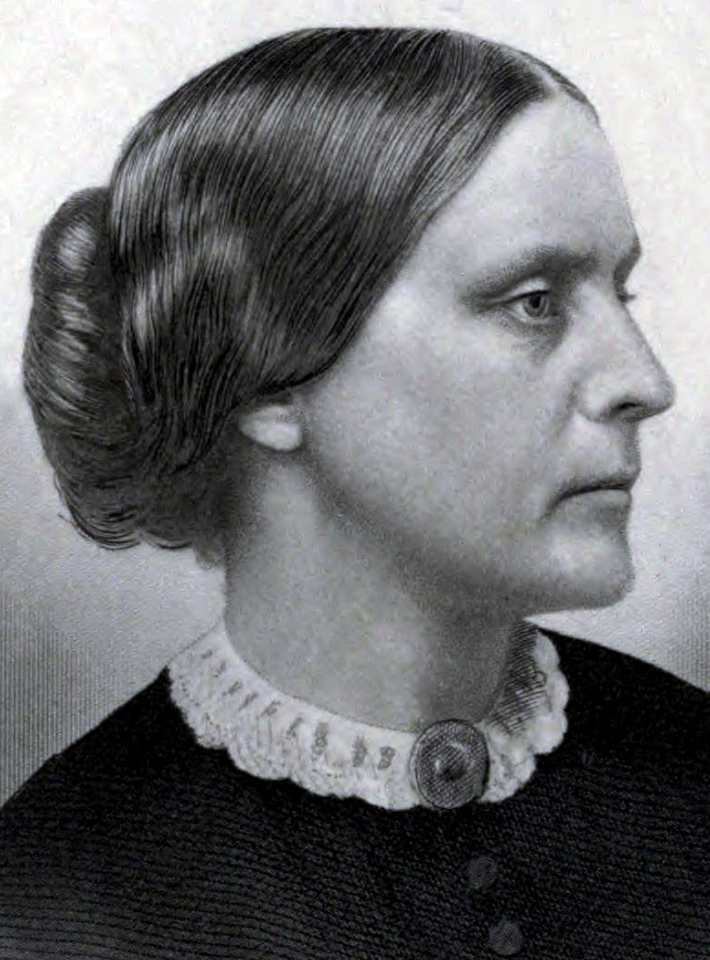

Susan B. Anthony

On this date in 1820, Susan Brownell Anthony was born in Massachusetts. She taught school from ages 15 to 30 before devoting her life to reform. She and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, starting in 1850, became lifelong feminist collaborators. The tireless crusader spent 30 years campaigning for women’s suffrage. Raised Quaker, she became a Unitarian but at the end of her life was an agnostic. Anthony’s professed “creed” was that of “the perfect equality of women,” according to Stanton.

While privately scolding Stanton for editing the controversial Woman’s Bible, Anthony publicly defended her: “I think women have just as much a right to interpret and twist the Bible to their own advantage as men always have interpreted and twisted it to theirs.” (Interview in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, quoted in The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony.) She also confessed, “But while I do not consider it my duty to tear to tatters the lingering skeletons of the old superstitions and bigotries, yet I rejoice to see them crumbling on every side.”

Her biographer Ida Husted Harper wrote that after Anthony visited a poor mother of six in Ireland in 1883, Anthony noted that “the evidences were that ‘God’ was about to add a No. 7 to her flock” and later commented, “What a dreadful creature their God must be to keep sending hungry mouths while he withholds the bread to fill them!”

There is no record she ever had a serious romance despite receiving marriage offers and would answer journalists’ questions with statements like “It always happened that the men I wanted were those I could not get, and those who wanted me I wouldn’t have.” To another she answered, “I never found the man who was necessary to my happiness. I was very well as I was.” She had no desire to “give up my life of freedom to become a man’s housekeeper.”

But according to Sted Mays, writing in the Gay & Lesbian Review, Anthony felt compelled to create a conventional public persona and made excuses for her unmarried status in order to hide her same-sex attractions: “She talked in interviews about not wanting to be trapped in a male-dominated relationship. But the real reason she never had a serious relationship with a man was that her passions were directed toward other women.” (“Stop Straightwashing Susan B. Anthony,” Feb. 10, 2020)

She died of heart failure at age 86 at her home in Rochester, N.Y. (D. 1906)

“I could not dash her faith with my doubts, nor could I pretend a faith I had not; so I was silent in the dread presence of death.”

— Anthony contemplating her sister on her deathbed, "The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, Vol. 2" by Ida Husted Harper (1898)

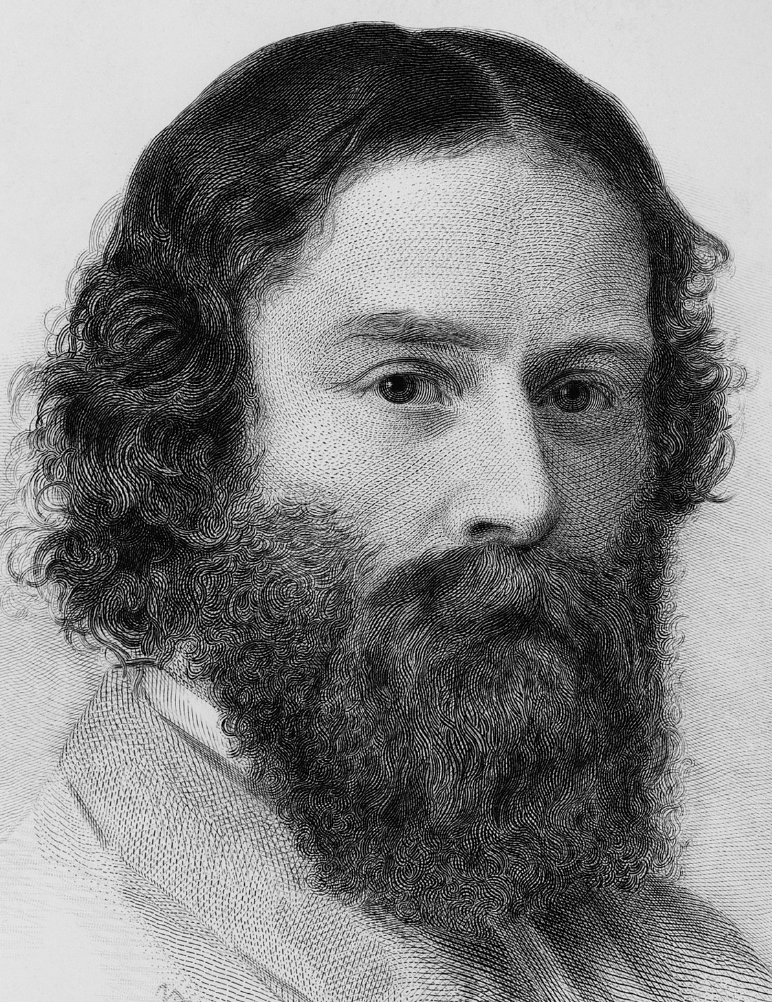

James Russell Lowell

On this date in 1819, poet James Russell Lowell was born in Cambridge, Mass., the son of a Unitarian minister in a family which went back eight generations in America. Lowell was one of the “Fireside Poets,” a group of New England writers that included Longfellow, Whittier and Holmes. Lowell earned his B.A. in 1838 and his L.L.B. in 1840 from Harvard. An ardent abolitionist, he left the law for literature, editing several journals.

He edited the Atlantic Monthly (1857-61) and the progressive North American Review (1864-72). A professor at Harvard for nearly 20 years, he also served as a minister to Spain and Great Britain. The poet wrote A Fable for Critics (1848), The Biglow Papers (serialized articles published in book form in 1848 and 1867) and The Vision of Sir Launfal (“And what is so rare as a day in June?”) in 1848.

Although Lowell’s poetry contains religious views that were conventionally 19th-century Unitarian, rationalist biographer Joseph McCabe suggested that, based on his later remarks, Lowell became agnostic. His later poetry included “The Cathedral “(1870), which dealt with the conflicting claims of religion and modern science.

He married the poet Maria White in 1844. They had four children, only one of whom survived childhood, before she died in 1853. He married Frances Dunlap in 1857. She died in 1885, six years before his death in 1891 at age 72.

“Toward no crimes have men shown themselves so cold-bloodedly cruel as in punishing differences of belief.”

— Lowell, "Literary Essays, Vol. II: Witchcraft" (1891)

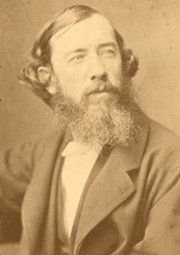

Moncure Daniel Conway

On this date in 1832, Moncure Daniel Conway was born into a conservative, pro-slavery family in Virginia. Becoming a Methodist minister at an early age, Conway soon gravitated toward Unitarianism. He graduated from Harvard Divinity School in 1854 as a Unitarian minister. Conway was much influenced by his “spiritual father,” Ralph Waldo Emerson, and abolitionist Theodore Parker.

By 1862, Conway, whose liberality had alienated his congregations, had dropped Unitarianism. He helped about 30 of his father’s slaves escape to freedom at the start of the Civil War. After embarking on an abolitionist speaking tour abroad, he was offered a position in 1863 at South Place Chapel in London, an independent and increasingly freethinking congregation. Under Conway’s tutelage, the chapel became an open-minded hub of new ideas, showcasing the day’s newsmakers and intelligentsia.

Conway, who had become an agnostic, is known for his Life of Paine (1892), the first major positive biography about the revolutionary. Conway researched and wrote other biographies, including one on Hawthorne. He also edited a four-volume edition of Paine‘s works and wrote several other books, such as Demonology and Devil Lore (1879). Conway, who had returned to America when his wife was dying, became an expatriate in Paris following his disgust with the U.S. war against Spain. (Theodore Roosevelt had even invited arch-critic Conway to join the Spanish.)

Conway completed his autobiography in 1904. When the South Place Ethical Society built its new facilities in Red Lion Square, London, in 1929, it named the building “Conway Hall.” Regular meetings are still held at Conway Hall every Sunday. Its library is adorned with portraits of freethinkers, including many of Conway. (D. 1907)

“Sunday was a day of just so much external restraint as public opinion absolutely demanded. I learned at last, as I came to be about seventeen, that my father was an entire freethinker, as much as I am now. It shocked me much, because he never taught me anything, allowed me to pick up religion from any one around me, and then scolded me because I embraced beliefs which he knew must condemn him.”

— "Autobiography: Memories and Experiences of Moncure Daniel Conway" (1904)

Stephen Pearl Andrews

On this date in 1812, abolitionist Stephen Pearl Andrews was born in Templeton, Mass., the youngest of eight children of a Baptist minister and his wife. Andrews was educated at Amherst, studied law in Louisiana and moved with his bride to Houston with the intent to work to make Texas a “free” (anti-slavery) state. In 1843 he was mobbed and barely escaped with his life. He lectured against slavery in England, seeking help from the British Anti-slavery Society. By 1847 he had moved to New York, where he became an expert in phonography.

Reputedly studying more than 30 languages, Andrews was considered the leading Chinese scholar in the U.S. and published “Discoveries in Chinese” in 1854. According to freethought biographer Samuel Putnam, Andrews proposed a “unity of law in the universe,” a principle he felt applied to science, philosophy and language. Accordingly, Andrews invented a universal language, “Alwato.”

The prolific tract writer, whose diverse subjects ranged from “Love, Marriage and Divorce” to “Ideological Etymology,” was a regular contributor to the leading freethought newspaper The Truth Seeker. He was also the author of several books on labor and wage theory and individualist anarchism. (D. 1886)

“I reject and repudiate the interference of the State, precisely as I do the interference of the Church.”

— Andrews, "The True Constitution of Government in the Sovereignty of the Individual" (1851)

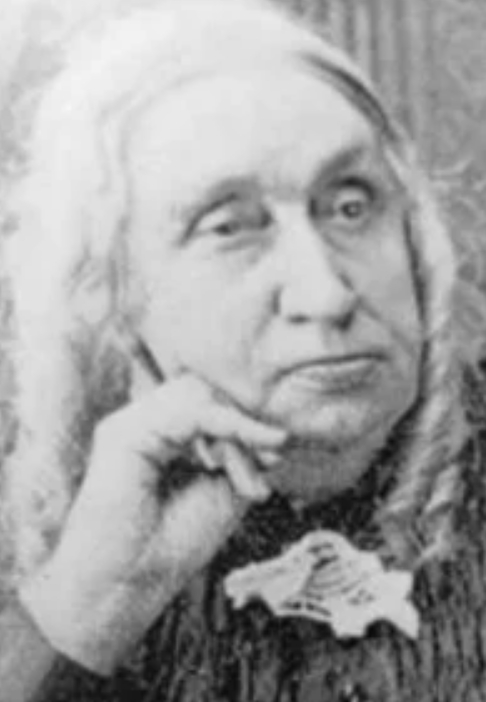

Lucy Colman

On this date in 1817, abolitionist infidel Lucy N. Colman (née Danforth) was born in New England, a descendant of John and Priscilla Alden through her mother’s side. She was twice widowed. When her second husband was killed in a work-related accident, she was left to support her 7-year-old daughter. With workplace door after door slammed in her face because of her sex, she discovered “woman’s wrongs.” She wrote, “I had given up the church, more because of its complicity with slavery than from a full understanding of the foolishness of its creeds.”

She turned to teaching in Rochester, earning less than half what a male teacher made. Susan B. Anthony discovered her and invited her to address a teachers’ association. She created a sensation by urging the abolition of corporal punishment in schools (see quote). She became an abolitionist lecturer, sacrificing security, comfort and wages to work against slavery. Often mobbed, she found that the racist ringleaders were nearly always clergymen. Frederick Douglass conducted the funeral for her daughter Gertrude, who died suddenly at college.

Colman later taught at a “colored school” in Georgetown and held many philanthropic positions. She wrote regular columns for the leading freethought publication, The Truth Seeker. She died at age 88 in Syracuse, N.Y. (D. 1906)

“If your Bible is an argument for the degradation of woman, and the abuse by whipping of little children, I advise you to put it away, and use your common sense instead.”

— Lucy Colman, paper delivered at New York teacher's convention (The Truth Seeker, March 5, 1887)

Helen Taylor

On this date in 1831, Helen Taylor was born in England. Her mother married John Stuart Mill in 1851. When her mother died seven years later, she took care of her esteemed stepfather and assisted Mill in writing his landmark Subjection of Women (1869). After his death in 1873, Taylor edited his Autobiography and Essays on Religion (1874). She was elected to the London School Board three times between 1876 and 1882 and championed disadvantaged children.

She agitated for abolition of school fees and for subsidized school meals and worked to stop abuses at industrial schools. In 1881 she joined the Social Democratic Federation, known as Britain’s first organized socialist political party. Taylor, a strong feminist and suffragist, attempted to run for Parliament in 1885 but her nomination papers were refused. (D. 1907)

“Religion should be taught by ministers of religion or by volunteer teachers, such as teachers of Sunday schools, and … the school master ought not to undertake the work of the clergyman, least of all when we have a church, the richest in the world, magnificently endowed to do its own work.”

— Helen Taylor (attributed, 1876)

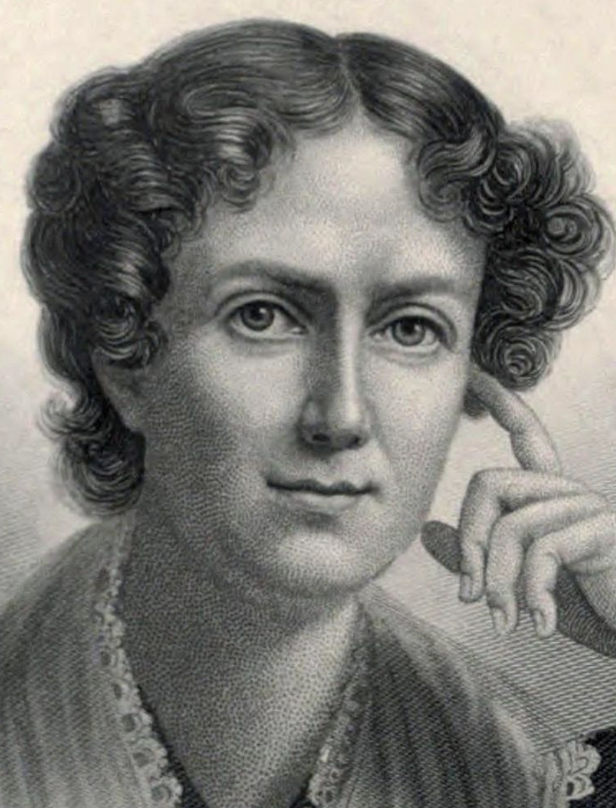

Frances Wright

On this date in 1795, Frances Wright, the first woman to publicly lecture in the United States, was born an heiress in Scotland. An arresting five feet, 10 inches as an adult, Wright influenced fashion of her day with her liberating style of ringlets and later her adoption of “Turkish trousers.” She traveled with her younger sister Camilla to America in 1818. Her play, “Altorf,” was staged to acclaim in New York in 1819, where she shocked society by using her byline as a female author.

Her travel book, Views of Society & Manners in America (1820), caused a sensation in Great Britain and abroad. Freethinker Jeremy Bentham became her mentor and General Lafayette her confidante. Returning at 29 to America, Frances became a U.S. citizen. As an early and passionate abolitionist, she began a noble but ill-fated model communal plantation to educate slaves for freedom at Nashoba, Tenn. They would have no religion but “kind feeling and kind action,” Wright decreed. The experiment unraveled for lack of money.

At 33, Wright launched her speaking career on July 4, 1828, in Cincinnati, seeking to “destroy the slavery of the mind” and counteract the effects of a religious revival on women, as well as the Christian Party in Politics movement. Wright called for the education of women and the rejection of religion. Her historic speaking tour won her adoration from progressives such as the young Walt Whitman, who recalled how “we all loved her: fell down about her.” But press and clergy dubbed Wright “The Red Harlot of Infidelity” and a “voluptuous preacher of licentiousness.”

Wright urged, “Turn your churches into halls of science, exchange your teachers of faith for expounders of nature. … Fill the vacuum of your mind!” Practicing what she preached, she purchased an old church in New York City for $7,000 and renamed it the “Hall of Science.” It opened its doors in April 1829 for lectures, a radical bookstore and at one time offered a health clinic. She and Robert Dale Owen launched The Free Enquirer and the Working Men’s Party, advocating a 10-hour workday, for which she was dubbed a “female Tom Paine” by the mayor of New York.

After an unsuccessful marriage to Frenchman Phiquepal D’Arusmont, resulting in the birth of a daughter, Wright returned to the U.S., where she lectured and wrote. When Wright divorced her husband, she tragically lost custody of her daughter. She broke her hip in a fall and died prematurely after great suffering in Cincinnati. D. 1852.

“I am not going to question your opinions. I am not going to meddle with your belief. I am not going to dictate to you mine. All that I say is, examine, inquire. Look into the nature of things. Search out the grounds of your opinions, the for and the against. Know why you believe, understand what you believe, and possess a reason for the faith that is in you.”

— Frances Wright, "Divisions of Knowledge" (1828)

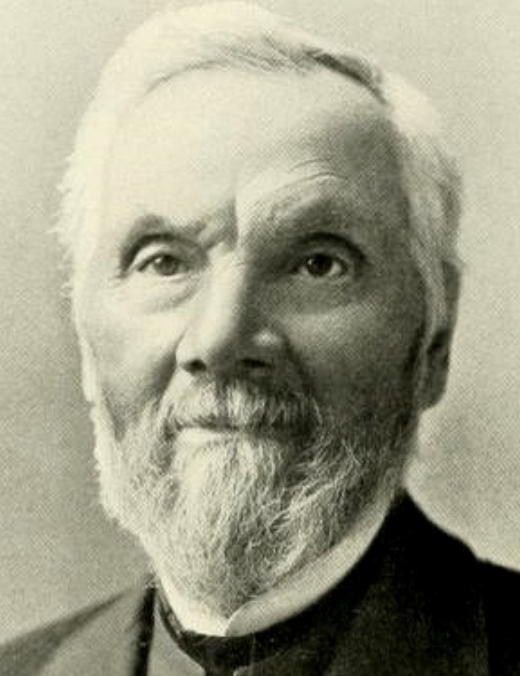

Parker Pillsbury

On this date in 1809, Parker Pillsbury, the freethinker, abolitionist and reformer, was born in Massachusetts. He became a licensed minister in the Congregationalist Church in 1839 after studying at Gilmanton and Andover theological seminaries. After preaching briefly, Pillsbury left the ministry over Congregationalist and other Christian complicity with slavery. He edited The Herald of Freedom (Concord, N.H.) in the 1840s and The National Antislavery Standard in New York City in 1866.

From 1843 until 1863, Pillsbury worked as an abolitionist agent and lecturer, rubbing shoulders with most of the notable reformers of his day. Pillsbury became sympathetic to the cause of women, who had to fight to be permitted to work on equal footing with male abolitionists. After the Civil War he collaborated with Elizabeth Cady Stanton as co-editor of the newspaper The Revolution, published by Susan B. Anthony. His writings include Acts of the Anti-Slavery Apostles (1883) and the critical Church As It Is: The Forlorn Hope of Slavery (1847).

Feminist Pauline Wright Davis lauded Pillsbury for his “good deeds and unselfish work. … His pen, wherever found, has always been sharpened against wrong and injustice.” (History, 1870.) He lectured widely on the “Free Religion” circuit in Ohio and Michigan and was vice president of the New Hampshire Woman Suffrage Association. He died at age 89 in 1899.

“The Methodist Discipline provides for ‘separate Colored Conferences.’ The Episcopal church shuts out some of its own most worthy ministers from clerical recognition, on account of their color. Nearly all denominations of religionists have either a written or unwritten law to the same effect. In Boston, even, there are Evangelical churches whose pews are positively forbidden by corporate mandate from being sold to any but ‘respectable white persons.’ Our incorporated cemeteries are often, if not always, deeded in the same manner. Even our humblest village grave yards generally have either a ‘negro corner,’ or refuse colored corpses altogether; and did our power extend to heaven or hell, we should have complexional salvation and colored damnation.”— Pillsbury letter, The North Star, Dec. 5, 1850

Stephen Symonds Foster

On this date in 1809, Stephen Symonds Foster was born in Canterbury, N.H. He graduated from Dartmouth College in 1838 and went on to enroll in Union Theological Seminary, where he became disheartened with the pro-slavery views of many churches. The principal of Union Theological Seminary offered Foster a bribe to stop discussing his position on slavery, but Foster declined and left the seminary after only a year.

He helped to organize the New Hampshire Young Men’s Anti-Slavery Society and was a member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, along with his wife, Abigail Kelley. Foster and Kelley were also strong supporters of women’s rights and the temperance movement. The family lived on a farm called Liberty Farm in Massachusetts, which they used to help slaves escape on the underground railroad.

Foster was an outspoken abolitionist who critiqued churches for their support of slavery, often interrupting services to rail against it. In 1844 he published the pamphlet “The Brotherhood of Thieves; or, a True Picture of the American Church and Clergy,” an exposé of the anti-abolitionist views of churches and the clergy. In the introduction he described it as a “testimony against the popular religion of our country.” (D. 1881)

“During the 1844 New England Antislavery Convention, Foster held up a collar and manacles and declared, ‘Behold here a specimen of the religion of this land, the handiwork of the American church and clergy.’ ”

— "The Puritan Origins of American Patriotism" by George McKenna (2007)

William Lloyd Garrison

On this date in 1805, anti-cleric and early abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison was born in Newburyport, Mass. Apprenticed to a newspaper at age 13, Garrison took up the abolition cudgels early. Sued for libel by the owner of a slave ship, he was convicted and sentenced to six months in prison, serving seven weeks. On the nation’s 50th anniversary, he wrote, “There is one theme which should be dwelt upon, till our whole country is free from the curse — SLAVERY.” He founded The Liberator in Boston in 1831. In its pages Garrison vowed, “I am in earnest, I will not equivocate, I will not excuse, I will not retreat a single inch, and I will be heard.”

He started the New England Anti-Slavery Society in 1832, then the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. He was especially critical of church complicity with slavery, not only in the South but in the North. Northern denominations refused to condemn slavery or sever ties with Southern slave-holding congregations.

The South Carolina city of Columbia offered a $1,500 reward for apprehension of anyone distributing The Liberator. The Georgia House of Representatives offered $5,000 for Garrison’s capture and trial. He narrowly evaded arrest there by fleeing to England. In 1835 he was dragged through the streets of Boston by a mob. The mayor rescued him by arresting him.

Garrison was an ardent “woman’s rights man” and early suffragist. He and other abolitionists and freethinkers attended a four-day bible convention “for the purpose of freely and fully canvassing the authority and influence of the Jewish and Christian Scriptures” in June 1853. More than 2,000 attended the event in Melodeon Hall in Hartford, Conn., a majority of them hostile, including 700 divinity students.

He was not a churchgoer or believer in orthodoxy, although he was deistic. The last issue of The Liberator was published in 1865. He remained active in progressive causes, especially suffrage. He died of kidney disease at age 73 in New York City. (D. 1879)

“The human mind is greater than any book. The mind sits in judgment on every book. If there be truth in the book, we take it; if error, we discard it. Why refer this to the Bible? In this country, the Bible has been used to support slavery and capital punishment; while in the old countries, it has been quoted to sustain all manner of tyranny and persecution. All reforms are anti-Bible.”

— Garrison remarks at the national woman's rights conference in Philadelphia, Oct. 18, 1854. "History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 1" (1887)