August 3

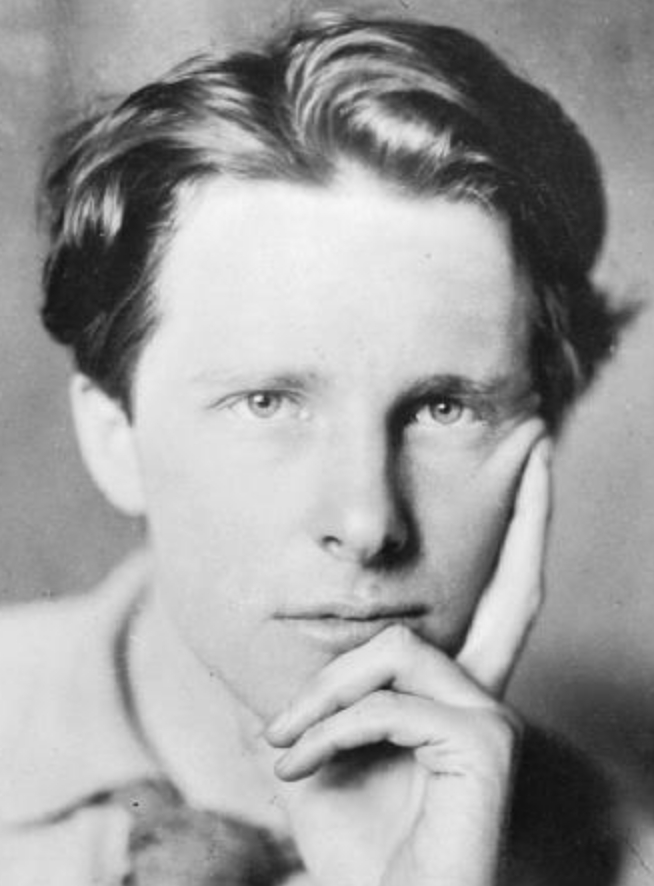

Rupert Brooke

On this date in 1887, Rupert Brooke was born in England. The Cambridge-educated poet became a celebrity among his Fabian Society peers. W.B. Yeats famously dubbed him “the handsomest young man in England.” Bertrand Russell, in his autobiography, recorded there was “no humbug” in Brooke. He traveled widely, including trips to North America and the South Seas. He edited an anthology of Georgian poetry and his own book, Poems 1911, came out the same year.

When World War I broke out in 1914, the 27-year-old became a sub-lieutenant in the Royal Navy. Weakened by a series of illnesses, Brooke died off the Greek island of Skyros of blood poisoning from an insect bite. He had only seen combat once, but his sonnet, “Soldier” and several other wartime poems, became celebrated during the early, war-fevered years. Winston Churchill wrote a patriotic obituary after his death. Brooke was at minimum a strong doubter. Below is an excerpt of his poem “Heaven.” Click here for an animated musical version by FFRF’s Kati Treu and Dan Barker. ( D. 1915)

Fish say, they have their Stream and Pond;

But is there anything Beyond?

This life cannot be All, they swear,

For how unpleasant, if it were!

One may not doubt that, somehow, Good

Shall come of Water and of Mud;

And, sure, the reverent eye must see

A Purpose in Liquidity.

We darkly know, by Faith we cry,

The future is not Wholly Dry.

Mud unto mud! — Death eddies near —

Not here the appointed End, not here!

But somewhere, beyond Space and Time.

Is wetter water, slimier slime!

And there (they trust) there swimmeth One

Who swam ere rivers were begun,

Immense, of fishy form and mind,

Squamous, omnipotent, and kind;

And under that Almighty Fin,

The littlest fish may enter in.— Rupert Brooke, "Heaven" (1913)

Michael Terence Wogan

On this date in 1938, Michael Terence “Terry” Wogan was born in Limerick, Ireland. When he retired from his BBC Radio morning program “Wake Up to Wogan” in 2009, he had about 8 million listeners, making it the most popular radio broadcast in Europe. He had started his career in 1963 with Radio Éireann, the Irish national broadcaster. He was educated by Salesian nuns in primary school and later at Crescent College and Belvedere College, both Jesuit schools.

In 1966, when his daughter Vanessa died at 3 weeks of age, his wife sought refuge in Catholicism but the tragedy cemented his nonbelief, Wogan said in 2005. He called losing his faith at age 17 a relief. Interviewed by New Internationalist magazine on Aug. 1, 2004, he said, “There were hundreds of churches, all these missionaries breathing fire and brimstone, telling you how easy it was to sin, how you’d be in hell. We were brainwashed into believing.”

Wogan branched out from strictly radio work to television game and interview shows. He was also the voice of the Eurovision Song Contest for many years and was involved with and hosted the Children in Need telethon since its inception in 1980. He acquired dual British citizenship in 2005, the same year he was knighted. “There was no one better at being a friend behind the microphone than Sir Terry,” said fellow broadcaster Simon Mayo. Wogan said the two most important attributes a person could have were kindness and family. He and his wife Helen Joyce had four children. He also wrote a column in The Sunday Telegraph for many years and wrote several books, including the autobiographies Is It Me? and Mustn’t Grumble.

When he died of cancer at age 77, The Telegraph’s obituary said he was “the most popular and best-loved broadcaster in Britain for more than three decades, confecting a middlebrow, old-fashioned brand of gentle Irish whimsy that barely concealed his forthright and often antagonistic views about the BBC and the people who run it.” (D. 2016)

PHOTO: Wogan at the 2015 Cheltenham Literature Festival; Julie Anne Johnson photo under CC 2.0.

“I’m afraid I don’t believe in God. My mother was devout and so is my wife. But I have the intellectual arrogance that makes it very hard to believe in him. I don’t have the gift of faith. I remember at school I used to make up sins at confession. What we were told were sins by priests were not sins at all.”

— The Sunday Independent (May 8, 2005)

John Landis

On this date in 1950, American director, producer, screenwriter and actor John Landis was born in Chicago. Landis, who was born into a Jewish family, began his career working as a mailboy for 20th Century Fox. When Landis was only 21 he made his directorial debut with “Schlock” (1971), but it was 1978’s “National Lampoon’s Animal House” that brought him commercial success, grossing over $120 million domestically. Landis co-wrote and directed “The Blues Brothers” (1980), starring John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd. “An American Werewolf in London” (1981) won the Academy Award for Best Makeup.

In 1982 Landis was charged with involuntary manslaughter for the death of actor Vic Morrow and two child extras during the filming of “Twilight Zone.” Morrow and the extras, Myca Dinh Le, 7, and Renee Shin-Yi Chen, 6, were trapped beneath a helicopter when it crashed due to special-effect explosions that went off too close to the tail rotor. Landis was riding in the copter when it crashed and suffered injuries. He was eventually acquitted of the charges and the families settled out of court with the film studio.

Landis would go on to direct many more blockbuster films, including “Trading Places” (1983), ”Three Amigos” (1986), ”Coming to America” (1988), “Beverly Hills Cop III” (1994) and “Blues Brothers 2000” (1998, co-writer with Dan Aykroyd). Landis directed the music videos for Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” (1983) and “Black or White” (1991).

Landis has spoken about his atheism on multiple occasions. He and his wife Deborah Nadoolman, an Oscar-nominated costume designer, have two children, Max and Rachel.

“I’m an atheist. I do not believe in the devil; in fact, I’m suspect of people who do.”

— Landis, Independent Film Channel interview (Nov. 23, 2011)

John T. Scopes

On this date in 1900, famed litigant John Thomas Scopes — defendant in the Scopes “monkey trial” — was born in Paducah, Ky., to Mary (Brown) and Thomas Scopes, the fifth of their five children and the largest at birth (12 pounds). He had four sisters: May, Ethel, Irene and Lela. Thomas Scopes was born in the slums of London and was nominally Anglican when he married his Presbyterian bride.

In his 1967 memoir “Center of the Storm: Memoirs of John T. Scopes,” he said his father read him excerpts from several works by Charles Darwin, which he read in their entirety when he was older. He attended Sunday school and church services regularly until his senior year in high school when an argument with the minister led to him leaving the church. His favorite authors were Dickens, Twain and Jack London. Each, Scopes wrote, tried “to show that civilization is a veneer and to warn us against accepting, without question, the soothsayers of the past.”

The elder Scopes, who embraced agnosticism later in life, also embraced trade unionism and Socialist icon Eugene V. Debs while working as a railroad machinist. His son followed in his footsteps in rejecting organized religion and its moralizing, believing that people’s well-being stemmed from economic justice. Scopes wrote, “Dad didn’t believe the products of poverty and ignorance could be improved by passing laws on morals or by running the whores out of town.”

Little did Scopes imagine that the bible-toting politician William Jennings Bryan, the commencement speaker at his 1919 high school graduation in Salem, Ill., would play a key part in his life in a few years. After three years at the universities of Illinois and Kentucky, Scopes still had no major, then chose law and graduated with a B.A. He took a job in 1924 teaching public high school math, physics and chemistry and coaching football for $150 a month in Dayton, Tenn. He started attending church again to socialize despite the “Repent ye, sinner, or suffer the consequences” sermons that permeated Protestant services, Scopes later wrote.

Bryan had surfaced in the area to attack the teaching of evolution theory and, in 1925, Tennessee passed the Butler Act that made it a crime “to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man had descended from a lower order of animals.”

When the regular biology teacher, who was also principal, declined to test the law in court because he was married with children and had family responsibilities, bachelor Scopes agreed to challenge it even though he had only filled in as biology teacher when the principal was gone. He wasn’t even sure he had covered evolution in class, having only assigned readings from a state-required textbook. Famed attorney Clarence Darrow led the defense team hired by the American Civil Liberties Union. Bryan agreed to represent the World’s Christian Fundamentals Association and was accepted by the state as a special prosecutor.

Journalist H.L. Mencken brought the case to the nation’s attention by labeling it the “monkey trial.” He reported: “The rustic judge, a candidate for re-election, has postured the yokels like a clown in a ten-cent side show, and almost every word he has uttered has been an undisguised appeal to their prejudices and superstitions.” The circus-like atmosphere in sweltering Dayton evoked worldwide interest, with 22 Western Union operators transmitting copy from a nearby grocery store. The all-male jury had six Baptists, four Methodists, one Disciple of Christ member and one man who didn’t belong to a church.

Scopes had been arrested on May 5. The trial opened on July 10. “Center of the Storm” covers the arguments in great, informative and often hilarious detail. On July 21, the jury brought in a guilty verdict after deliberating nine minutes. The judge imposed a fine of $100. Scopes told him the conviction and fine were unjust: “I will continue in the future, as I have in the past, to oppose this law in any way I can.” Bryan died in his sleep five days later.

On appeal, the state Supreme Court upheld the law’s constitutionality but overturned the conviction on the grounds that the fine was excessive because it was over the $50 maximum that could be levied by judges. Only juries could exceed that limit. The state chose not to retry the case. Not until 1967 did Tennessee repeal its anti-evolution statute.

Scopes was offered but declined to accept a new contract at the Dayton school due to the case’s notoriety. Instead he enrolled in a graduate geology program at the University of Chicago before joining Gulf Oil as a field engineer on Venezuela’s Lake Maracaibo. He later worked as an oil scout out of Beeville, Texas, then in the company’s Houston office and in Shreveport, La., where he stayed until retiring in 1964.

In his memoir, Scopes wrote about courting Mildred Walker — whose father also worked in Venezuela — whom he married in 1930. “She was a Roman Catholic and to please her I agree to be married in her church. …. News stories subsequently made a point of my being a member of the Catholic Church; I emphasized to all who interviewed me that I had done this simply to please my bride.” He took Catholic instructions to prepare. “The priest in Maracaibo surely realized I couldn’t accept everything he told me I should believe. A good agnostic couldn’t give up his faith that easily. Nevertheless I politely listened to his instructions and I was baptized. I have not since been a communicant.” They remained married until Scopes’ death and had two sons, John Jr. (b. 1932) and William (b. 1936).

In a 1961 letter to journalist and film critic Harold Salemson, he wrote about touring to promote the 1960 movie “Inherit the Wind,” a fictionalized version of the case. A stage production had debuted in 1955. A Shreveport Methodist congregation had invited him to speak, and to the standing-room-only gathering Scopes said, ” ‘I am an agnostic member of a Catholic family and would like to tell a Methodist group how to think —.’ They loved it.”

According to John Scopes Jr., his aunts Lela and Ethel became the boys’ de facto parents for about three years (“pawned us off on my father’s sisters”) due to their parents’ alcoholism. (The American Biology Teacher, February 2020) Scopes died of cancer at age 70 in Shreveport, preceding his wife in death at age 85 in 1990. At Lela’s suggestion, “A Man of Courage” was engraved on Scopes’ tombstone. (D. 1970)

PHOTO: Scopes in 1925; Library of Congress photo

“Of course, it was impossible to teach biology without teaching evolution. But to the fundamentalists, evolution symbolized all that was repugnant. It was a threat to religious belief, they thought. They equated evolution with agnosticism, which in turn they made synonymous with atheism.”

— "Center of the Storm: Memoirs of John T. Scopes" (1967)