September 13

Don Addis

On this day in 1935, Donald Gordon Addis was born in Hollywood, Calif., on a Friday the 13th. He grew up in (where else) Hollywood, Fla., and in 2004, after a long career as a freethinking editorial cartoonist and columnist with the St. Petersburg Times, he retired, on a (what else) Friday the 13th. Addis was an FFRF Lifetime Member and his cartoons have long been a treasured part of FFRF publications. Addis received the foundation’s Freethought in the Media “Tell It Like It Is” award at the 2005 national convention in Orlando.

Addis had a degree in design from the University of Florida, where he also edited the Orange Peel, then ranked as the nation’s No. 1 college humor magazine. He also served as editorial cartoonist on his college newspaper, The Alligator, as he did on his U.S. Army newspaper before that. He won 16 awards for cartooning from the Armed Forces Press Service. His work included the comic strips “Briny Deep” (1980), “The Great John L.” (1982–84), “Babyman” (1985) and “Bent Offerings” (1988–2004). He received the National Cartoonist Society Newspaper Panel Cartoon Award for 1992 for “Bent Offerings.”

He was awarded the National Cartoonists Society prize for Best Newspaper Panel Cartoon for 1993. He won the Florida Education Association School Bell Award for cartoons in the field of education four years in a row and several first places in the Florida Newspaper Illustrator and Cartoonists contest. He was named its Cartoonist of the Year. He also is recipient of the Ignatz Award (named for the Krazy Kat character) presented by his peers.

In his farewell column in the St. Petersburg Times, Addis said this to those who complained over the years that his work was not balanced or objective: “Objectivity is not my department. Balance is down the hall. Impartiality is another word for no reason to draw a cartoon.” He died at age 74 of lung cancer was survived by his wife Christi, three daughters and a son. His obituary in the Times gave a flavor of the man: “Though loyal to friends and family, Mr. Addis was not gregarious. While others partied though the holidays, he preferred to stay home with a book, where a welcome mat still reads ‘GO AWAY.’ He bought smelts for an egret in the neighborhood, which stalked him regularly.” (D. 2009)

“Do you have any weapons, flammable materials or hazardous religious beliefs?”

— Text with Addis cartoon showing a Native American checking a Mayflower pilgrim's suitcase

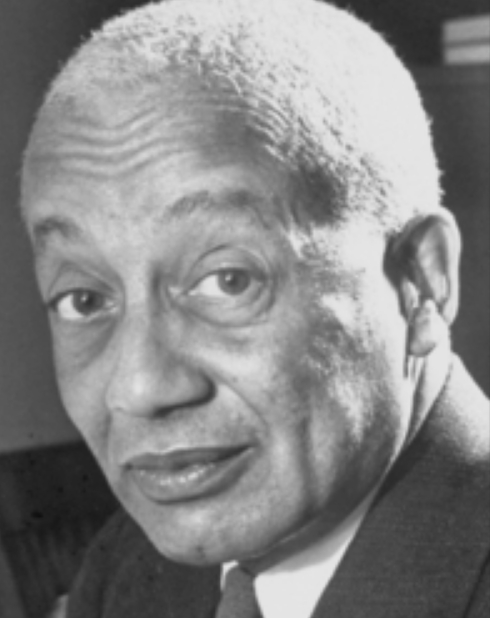

Alain Locke

On this date in 1885, philosopher and author Alain LeRoy Locke, an instrumental figure in the Harlem Renaissance, was born in Philadelphia, the only child of Pliny Ishmael Locke — a law school graduate and the first black employee of the U.S Postal Service — and Mary Hawkins Locke, a teacher. His father died when Locke was 6, when he became even closer to his mother, who was an adherent of Felix Adler.

He was the first African-American Rhodes Scholar and went on to earn a Ph.D. in philosophy from Harvard University. It would be 56 years before another Black was awarded the Rhodes. The family’s religious background was Episcopalian, which Locke later disavowed when he became convinced the Baha’i faith with its “universalist” and humanist views and interracial meetings appealed more to him as a person of color. He would be reprimanded in 1920 while teaching at Howard University for his failure to attend chapel. He had received an assistant professorship there in 1912.

In The Philosophy of Alain Locke: Harlem Renaissance and Beyond (1989), editor Leonard Harris wrote, “Contrary to a Christian doctrine that there exists only one route to salvation, Locke holds that true universality requires a different view of spiritual brotherhood — one compatible with world peace.” In that same book Locke is quoted, “The idea that there is only one true way of salvation with all other ways leading to damnation is a tragic limitation [of] Christianity, which professes the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. How foolish in the eyes of foreigners are our competitive blind, sectarian missionaries!”

In a 2019 profile in The Humanist, Charles Murn wrote that Locke engaged in the culture wars of his time: “He attacked racism, color prejudice, discrimination against minorities, anti-Semitism, eugenics, and imperialism. While he was gay and mentored younger gay men, many of whom were artists, he did not seek to ease restrictions on homosexuality. He called for religious tolerance, yet confronted intolerance by religious leaders.”

Locke possessed a towering intellect (while physically small in stature at 4-foot-11), and after he was fired as chair of Howard’s philosophy department in 1925 for demanding pay equity for Black faculty, focused on publishing The New Negro: An Interpretation. A landmark in Black literature, the anthology contained Locke’s title essay and four more he wrote, along with poetry, art and prose by others, including Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes.

After being reinstated at Howard in 1928, he remained there until retiring in 1953. Leonard Harris notes that between 1912-53, most of the Black philosophy students at U.S. universities were either taught by Locke or by the philosophers he was instrumental in hiring at Howard. He also influenced students during visiting professorships in the mid-1940s at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the New School for Social Research in New York City. The philosophy department at UW-Madison was chaired at that time by Max Carl Otto, one of the earliest and most prominent scientific humanist philosophers.

He died of heart disease in New York City the year after retiring. Engraved on the tombstone under which lay his ashes is “Herald of the Harlem Renaissance” and “Exponent of Cultural Pluralism.” On the back are engraved a nine-pointed Baháʼí star, a bird that’s the national emblem of Zimbabwe, lambda gay rights and Phi Beta Sigma symbols and an African woman’s face set against the sun’s rays. Beneath the images are the Latin words “Teneo te, Africa” (I hold you, Africa). (D. 1954)

“The best argument against there being a God is the white man who says God made him.”

— Locke, quoted in "Alain Locke: Faith and Philosophy" by Christopher Buck (2005)

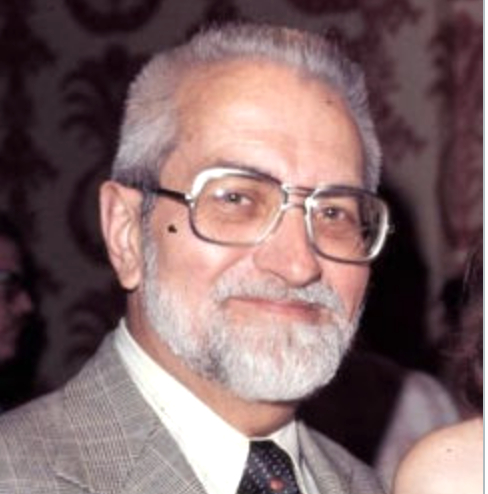

Herb Grosch

On this date in 1918, computer science pioneer Herbert Reuben John Grosch was born in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, to English emigrants Bessie (Adams) and Reuben Grosch. His father was a skilled cabinet maker who later supervised others in the craft. Grosch was their only child.

His parents attended Anglican services, at least until Grosch at age 9 refused to attend anymore and they stopped going. “Mother later in life developed a reasonable amount of religiosity again and started going a few times a year,” Grosch later said. “I think Dad used to drive her there and leave her and pick her up again at the end of the service.” (Oral interview, Aug. 26, 1970, National Museum of American History)

After his father started working in the U.S., Grosch went to school in Toledo, Ohio, and graduated from high school in the Detroit suburb of Royal Oak, Mich. Enrolling at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, he studied astronomy, astrophysics and celestial mechanics, eventually earning a Ph.D. in astronomy there in 1942.

He took a position at the U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C., in 1941, the year he married Dorothy Carlson in a Lutheran service. She was an astronomical assistant at the Mount Wilson Observatory in Pasadena, Calif. Six years his senior and suffering from depression, she died in 1956 from an overdose of sleeping pills when he was 38.

Not long after her death, Grosch married a teacher, Elizabeth Yeager, whom he’d known while they were in junior high in Toledo. After divorcing, he married Joyce Winn, a divorcée with two young sons, in 1965. They divorced in 1972. Three years later, he married Nancy Hall, who died of cancer in 1996. “I only go to churches to get married,” Grosch later said. “But I always seem to marry people that want to go to church. Although they also turn out only to go to church to get married.” (Ibid.)

Grosch has done pioneering computer work with IBM, General Electric, the federal government and other organizations in the U.S. and overseas. He worked on atomic bomb calculations as part of the 1940s Manhattan Project and was friends with Werner von Braun.

In 1953 in the Journal of the Optical Society of America, he wrote: “I believe that there is a fundamental rule, which I modestly call Grosch’s law, giving added economy only as the square root of the increase in speed — that is, to do a calculation ten times as cheaply you must do it a hundred times as fast.” It became the basis for the aphorism, “Economy is the square root of speed.”

He held a Columbia University professorship from 1946-51 and various others of shorter duration at Arizona State, Boston University, New Mexico State, the University of Nevada-Las Vegas and the University of Toronto. He was editor of the journal Computerworld (1973-76) and president of the American Rocket Society (later the Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics).

Brian Hayes, American Scientist columnist and editor-in-chief, wrote in 2010 that Grosch cultivated the role of an outsider who saw himself as a lone wolf. “Even when he was an insider he was an outsider. Grosch was elected president of the Association for Computing Machinery — but as a dissident candidate, opposing the slate anointed by the nominating committee.” He died at age 91. (D. 2010)

“I made them quit, essentially. When I was nine years old I decided that I was an atheist. So I told them, ‘Well you shouldn’t go to church anymore, it’s silly.’ Well, apparently they’d been going to church primarily for my benefit. So after I refused to go, they quit going too.”

— Grosch, answering if his parents attended church regularly. Interview, National Museum of American History (July 15, 1970)