womens-rights-activists

Alice Paul

On this date in 1885, feminist Alice Stokes Paul was born in Moorestown, N.J., to a Quaker family which believed in the equality of the sexes. She attended Swarthmore College, then spent a year as a student at the New York School of Philanthropy while working at a settlement house. Paul earned a master’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania in economics and sociology, then won a fellowship to study in England. She took courses at the University of Birmingham and London School of Economics and worked in the British settlement movement.

Paul was arrested and jailed several times in England for joining in brick-throwing at government buildings and took part in hunger strikes. Returning to New Jersey in 1910, she lectured in favor of adopting the British militancy. That year she stopped speaking to Quaker groups after her views were repudiated by them and transferred her allegiance to pure feminism. Like Quaker-raised Susan B. Anthony, Paul became an agnostic, according to Warren Allen Smith in Who’s Who in Hell. Her story inspired the 2004 HBO film “Iron Jawed Angels” in which she was portrayed by Hilary Swank.

Teaming up with her New York friend Lucy Burns, Paul talked the National American Woman Suffrage Association into letting them take over its congressional committee with help from Jane Addams, in 1912. They set up shop in Washington, D.C., organizing a historic parade of suffragists on March 3, 1913, upstaging the inauguration of President Woodrow Wilson. Peacefully parading women were attacked by a violent mob, which created huge headlines and reinvigorated the suffrage campaign.

During World War I, Paul and supporters picketed the White House with placards asking “How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?” When mobs attacked, police arrested more than 100 suffragists, many of whom were sentenced to notorious workhouses. Paul and other hunger strikers were force-fed, and she was even transferred to a psychiatric hospital. The public outcry forced Wilson to unconditionally release the women. Demonstrations continued and Congress finally enacted the suffrage amendment, ratified by the states in 1920.

Paul went to law school, earning three degrees, then began promoting the Equal Rights Amendment, which she called the Lucretia Mott Amendment. Many women’s groups at the time, including the League of Women Voters and Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, opposed the ERA on the grounds that women needed protective legislation. The amendment was first introduced into Congress in 1923. Paul lobbied for it in every successive session until 1972, when it passed. The combined forces of the tax-exempt religious lobbies defeated the ratification process in 1982 after it failed to gain support in the required number of states.

Paul, who never married, died at age 92 at a Quaker facility in New Jersey, less than a mile from her birthplace. (D. 1977)

PHOTO: Paul in 1915.

"Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex."

— From the Equal Rights Amendment drafted by Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman

Helen H. Gardener

On this date in 1853, freethinker and suffragist Helen H. Gardener, née Alice Chenoweth, was born in Virginia, the youngest daughter of a Protestant minister who had inherited slaves but freed them in 1853 despite existing legal obstacles. Changing her name in her 30s, she became a writer in New York City, studied biology at Columbia and met “the Great Agnostic” Robert Green Ingersoll, who encouraged her to undertake a lecture series. The lectures were published in 1885 in book form, Men, Women and Gods.

A friend of feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Gardener was a member of Stanton’s Woman’s Bible Committee. Chosen by Stanton to deliver her memorial service, Gardener quipped that while most suffragists found the Woman’s Bible too radical, she found it not radical enough! She also used fiction to crusade for women’s rights, writing novels, for example, showing the harm of the scandalously low age of consent laws of her era.

In her 1885 book Men, Women, and Gods, she wrote: “I do know that women make shirts for seventy cents a dozen in this [world]. I do know that the needs of humanity and this world are infinite, unending, constant, and immediate. They will take all our time, our strength, our love, and our thoughts; and our work here will be only then begun.”

She became vice president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1917, working as chief liaison with President Woodrow Wilson’s administration, and credited with being a “worker of miracles” by sister suffragists. At age 67 she became the first woman appointed to the U.S. Civil Service Commission, serving with distinction for five years.

She died at 72 of myocarditis. She had donated her brain for scientific study before her body was cremated and its ashes interred at Arlington National Cemetery beside the grave of her second husband. Her brain is housed as part of a collection at Cornell University. (D. 1925)

PHOTO: Gardener at age 41.

"I do not know of any divine commands. I do know of most important human ones. I do not know the needs of a god or of another world.”

— Gardener, "Men, Women, and Gods, and Other Lectures" (1885)

Robin Morgan

On this date in 1941, Robin Morgan — feminist author, journalist, editor, lecturer, organizer, atheist and activist — was born in New York City. As she notes in her memoir, Saturday’s Child, “Saturday’s child has to work for a living.” She started at age 2 as a tot model. She had her own radio show by age 4, then acted in the role of Dagmar on the popular series “Mama” in the 1940s and 1950s. She left show biz to write and became a founder and leader of the contemporary feminist movement.

Morgan’s columns and articles for Ms. magazine appeared from 1974-88. She was editor-in-chief of Ms. for four years and later its international consulting editor. Her groundbreaking anthology Sisterhood Is Powerful came out in 1972, followed by Sisterhood Is Global (1984), Sisterhood Is Forever (2003) and Fighting Words: A Toolkit for Combating the Religious Right (2006). Morgan is a distinguished poet and the author of more than 20 books, including her 2006 novel The Burning Time, based on the first witchcraft trial in Ireland.

She has traveled the globe as a feminist activist, scholar, journalist and lecturer. She is a co-founder of the Feminist Women’s Health Network, the Feminist Writers’ Guild, Media Women and the National Network of Rape Crisis Centers. Her timely The Demon Lover: On the Sexuality of Terrorism tells the personal story of her travel to refugee camps in the Middle East, with a post-9/11 introduction and afterword. A recipient of many awards, she was named FFRF’s Freethought Heroine in 2005 and is an honorary director.

She was married from 1962-83 to poet Kenneth Pitchford, a founding member of the Effeminist movement. He and Morgan, who are both bisexual, have a son, musician Blake Morgan.

She was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2010. Instead of curtailing her effectiveness, the diagnosis inspired her to take the lead in creating the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation’s Women and PD Initiative to help women be better served by research, treatment and assistance for their caregivers. Morgan has shared her struggle with the disease by writing and presenting about her experiences at a variety of venues, including her 2015 Ted Talk, viewed over a million times. In 2018 she published Dark Matter: New Poems, which includes the verses from that presentation.

“Religion is not about awe and joy, despite its purported proprietorship of these and its promise to eventually deliver what already lies around us every day, freely available for utter celebration. Religion is about something else. The etymology of the word itself, from the Latin, to being ‘bound by rules.’ Religion is about terror.”

— Freethought Heroine acceptance speech at FFRF's national convention (Nov. 11, 2005)

Aletta Jacobs

On this date in 1854, women’s rights pioneer Aletta Henriette Jacobs was born the eighth of twelve children to Jewish parents in Sappemeer, the Netherlands. Jacobs wanted to be a physician like her father and brother at a time when there were no female doctors in the Netherlands. She was admitted first to Groningen University and then to Amsterdam University as the only woman studying medicine at each institution. She founded the first birth control clinic in the world in Amsterdam in 1882 and earned her doctorate the following year.

In 1884 she married Carel Gerritsen, a feminist and alderman of Amsterdam and member of the Dutch parliament. Since neither were religious, they opted for a civil ceremony, uncommon for the time. She started a medical practice specializing in treating women and children (often treating poor women for free), which she ran for 25 years.

She assembled a library of about 2,000 women’s studies books in German, French, Dutch and English titles — languages she was fluent in — now housed at the University of Kansas. She retired from medicine in 1903, the year Gerritsen died, to devote her life to feminism and pacifism.

Jacobs embarked on a woman’s suffrage world tour with Carrie Chapman Catt in 1911, asserting that suffrage was the most important means for women’s emancipation. She headed the Dutch Woman Suffrage Association, founded in 1894, and often participated in the International Women’s Suffrage Alliance, presided over by Catt. By the time her memoir was published in 1924, women had gained the right to vote in Holland and many other European countries.

In a letter Jacobs wrote to Catt in 1928, the year before her death, she said: “My dear Carrie, I feel sure we have not lived for nothing. We have done our task and we can leave the world with the conviction that we have left it in a better condition than we have found it.” (D. 1929)

“As a freethinker, she belonged to no organized religious community and disliked religion of any kind.”

— Harriet Feinberg, editor of Jacobs' memoir "Memories: My Life as an International Leader in Health, Suffrage, and Peace" (1996)

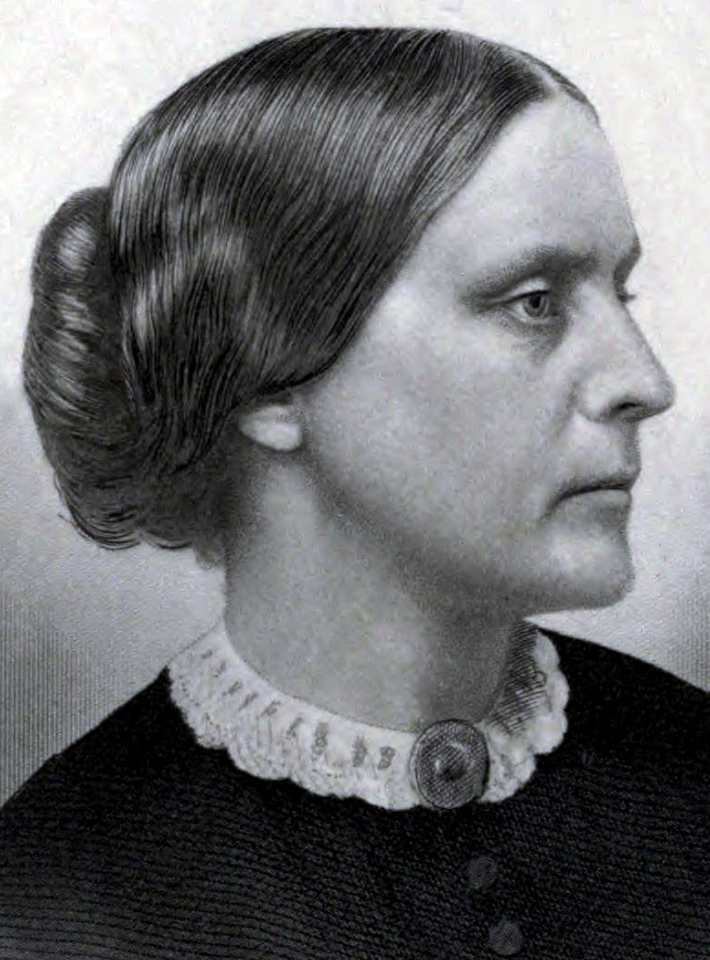

Susan B. Anthony

On this date in 1820, Susan Brownell Anthony was born in Massachusetts. She taught school from ages 15 to 30 before devoting her life to reform. She and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, starting in 1850, became lifelong feminist collaborators. The tireless crusader spent 30 years campaigning for women’s suffrage. Raised Quaker, she became a Unitarian but at the end of her life was an agnostic. Anthony’s professed “creed” was that of “the perfect equality of women,” according to Stanton.

While privately scolding Stanton for editing the controversial Woman’s Bible, Anthony publicly defended her: “I think women have just as much a right to interpret and twist the Bible to their own advantage as men always have interpreted and twisted it to theirs.” (Interview in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, quoted in The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony.) She also confessed, “But while I do not consider it my duty to tear to tatters the lingering skeletons of the old superstitions and bigotries, yet I rejoice to see them crumbling on every side.”

Her biographer Ida Husted Harper wrote that after Anthony visited a poor mother of six in Ireland in 1883, Anthony noted that “the evidences were that ‘God’ was about to add a No. 7 to her flock” and later commented, “What a dreadful creature their God must be to keep sending hungry mouths while he withholds the bread to fill them!”

There is no record she ever had a serious romance despite receiving marriage offers and would answer journalists’ questions with statements like “It always happened that the men I wanted were those I could not get, and those who wanted me I wouldn’t have.” To another she answered, “I never found the man who was necessary to my happiness. I was very well as I was.” She had no desire to “give up my life of freedom to become a man’s housekeeper.”

But according to Sted Mays, writing in the Gay & Lesbian Review, Anthony felt compelled to create a conventional public persona and made excuses for her unmarried status in order to hide her same-sex attractions: “She talked in interviews about not wanting to be trapped in a male-dominated relationship. But the real reason she never had a serious relationship with a man was that her passions were directed toward other women.” (“Stop Straightwashing Susan B. Anthony,” Feb. 10, 2020)

She died of heart failure at age 86 at her home in Rochester, N.Y. (D. 1906)

“I could not dash her faith with my doubts, nor could I pretend a faith I had not; so I was silent in the dread presence of death.”

— Anthony contemplating her sister on her deathbed, "The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, Vol. 2" by Ida Husted Harper (1898)

E.B. Foote

On this date in 1829, reformer Edward Bliss Foote was born in Cleveland, Ohio. He was brought up in a conforming Presbyterian household. Foote was a physician with a hand in the newspaper business, publishing the first newspaper in New Britain, Conn. Becoming a Unitarian, then an agnostic, he befriended D.M. Bennett, publisher of The Truth Seeker. Foote was the only foe of the first Comstock bill, which was introduced in the New York legislature in 1872, and passed despite his efforts.

The repressive Comstock Act was soon adopted by Congress, creating censorship of the press through postal regulations. Comstock went after his early foe in 1874, charging Foote with violating postal laws for mailing an educational pamphlet advocating the right of families to limit their size through “contraceptics.” He was fined $3,500 by Judge Benedict of the U.S. Circuit Court of the Southern District of New York in 1876.

Foote helped to organize the National Defense Association seeking repeal of the Comstock laws and aided other Comstock victims. He worked actively within medical societies and at the state legislature to oppose the legitimization of Christian scientists and faith healers. A lifelong advocate of woman’s suffrage, he sent a check of $25 to Susan B. Anthony when she was fined $100 for voting in the 1872 presidential election. He was a member of numerous freethought and professional groups. His son Edward Bond Foote also became a physician and freethinker. (D. 1906)

Gerald H.F. Gardner

On this date in 1926, mathematician Gerald Henry Frazier Gardner was born in Tullamore, Ireland. He studied mathematics and theoretical physics at Dublin’s Trinity College. He earned a master’s in applied mathematics from Carnegie Institute of Technology (1949) and a doctorate in mathematical physics from Princeton (1953). Gardner worked in applied seismology for several decades and taught at Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University), Rice University and the University of Houston.

Gardner actively pursued equal rights for women. Along with his wife, the former Jo Ann Evans, he was an early member of the Pittsburgh chapter of the National Organization for Women. Evans, a Ph.D. experimental psychologist, adopted the surname Evansgardner when they married in 1950.

Gardner and the chapter in 1969 challenged sex-based employment ads in the Pittsburgh Press. Employment want ads used to list separate categories for “Male Wanted” and “Female Wanted,” which barred women from much professional work. Gardner specifically provided statistical analysis of the likelihood of women finding employment in such a structure. This led to a landmark women’s rights decision in 1973 by the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld a Pittsburgh ordinance that prohibited sex-based employment advertisements.

As a result, want ads were “desexregated” around the nation, a huge boon for women’s employment rights. Gardner contributed statistical analysis in other cases involving gender and race discrimination and considered this work the most important of his life (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 27, 2009.) He and his wife were Life Members who joined FFRF in the late 1970s and left a generous bequest. Gardner died of leukemia at age 83 in 2009. Jo Ann died in 2010.

He "was an activist atheist, a proselytizing atheist. He thought that not saying you were an atheist hurt the cause of reality."

— Jo Ann Evansgardner, remembering her husband in his New York Times obituary (July 28, 2009)

Joseph Fletcher

On this date in 1905, Joseph Francis Fletcher III was born in Newark, N.J. He received a B.A. from West Virginia University before going on to receive a bachelor of divinity from Berkeley Divinity School in 1929 and a doctor of sacred theology from the University of London in 1932. He was ordained an Episcopal priest, but later renounced his belief in God and identified as a humanist.

Fletcher was a philosopher and a theologian whose work in the field of biomedical ethics was pioneering. Even when he was religious, his ethics were humanist, based on human suffering and consequences rather than biblical rules. He was an advocate for family planning, abortion, euthanasia and the sterilization of unfit parents.

He taught Christian ethics and pastoral theology at the Episcopal Theological School from 1944 to 1970, and medical ethics at the University of Virginia at Charlottesville from 1970 to 1977. He wrote several books, including Morals and Medicine (1954), Situation Ethics (1966), and Humanhood: Essays in Biomedical Ethics (1979). He was also a founding member of Planned Parenthood, the Association for Voluntary Sterilization, Society for the Right to Die and the Soviet-American Friendship Society.

In an autobiographical essay published posthumously in Memoir of an Ex-Radical, Fletcher describes his loss of faith at age 65, which he says was at first prompted by a realization that the church would never be a significant advocate in the social justice movement. He wrote: “[This realization] forced me to take a hard look at Christian doctrine itself, on its own merits: God, Jesus, revelation, sin, salvation — the whole repertory. Looking at it like that, I said to myself what I no doubt often glimpsed along the way, that the whole thing was weird and untenable.”

After this experience, Fletcher did not immediately resign from his position at the Episcopal Theology School. He called himself “an alienated or unbelieving theologian.” (D. 1991)

"[W]ith an absolute God, his word revealed and his will eternal, how could relativity in ethics get anywhere with them?"

— Fletcher explaining the outraged response from Christians, Muslims and Jews to his idea of situational ethics, ("Memoir of an Ex-Radical," 1993)

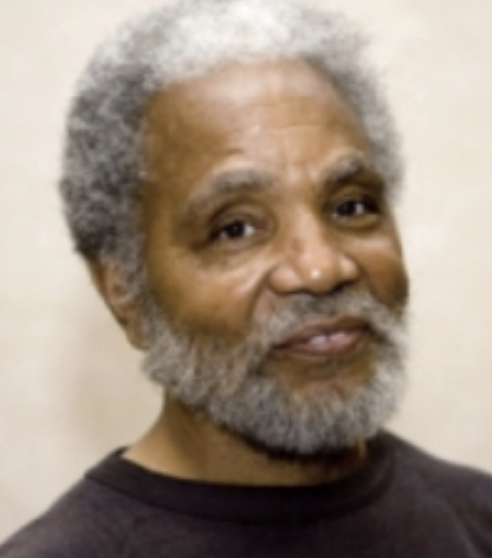

Ernie Chambers

On this date in 1937, politician Ernest Chambers, known as “the Maverick of Omaha” and “defender of the downtrodden,” was born in Omaha, Neb. Chambers understood early on the power of protest and of grassroots organizing, standing up for civil rights as a youth and emerging as a leader of African-American youths in Omaha. He graduated from Creighton University School of Law and was first elected to the unicameral legislature as a state senator in 1970, the only black member of the legislature in an overwhelmingly white, ultraconservative state.

Chambers became known for defending the rights of women, gays and lesbians and people of color. He challenged legislative prayers in the 1983 Supreme Court case Marsh v. Chambers, and although the court ruled against him, Chambers was successful in subsequently persuading the Senate to drop payment for prayers.

Rita Swan of Children’s Healthcare is a Legal Duty (CHILD) said in 2005, “Nebraska is the only state in the country that has never had a religious exemption to child neglect in either the juvenile or criminal codes and that distinction is due to Ernie’s forceful opposition and vigilance. Nebraska is one of four states without a religious exemption to metabolic screening of newborns and that again is because of Ernie’s leadership.” CHILD presented Chambers with its child advocacy service award for successfully arguing that “no parent should have a religious right to deprive a child of necessary health care” and keeping a religious exemption to health care from being enacted in that state.

Chambers cleverly filed a lawsuit in 2007 (Chambers v. God) to make a point about frivolous lawsuits. Chambers, who identifies as nonreligious without using a label, sought a permanent injunction against the defendant for making terroristic threats against him and his constituents, of inspiring fear and causing “widespread death, destruction and terrorization of millions upon millions of the Earth’s inhabitants.” In October 2008 the judge threw out his lawsuit, whimsically ruling that the defendant wasn’t properly served due to his unlisted home address.

Chambers, accepting FFRF’s Hero of the First Amendment Award in 2005, commented, “What I would do, from time to time, is mock, taunt, and ridicule my colleagues for injecting religion and Jesus into the legislature.” His political opponents, in a successful effort to finally unseat him from the Senate when they could not do so electorally, passed a law in 2000 establishing term limits so he was unable to seek reelection in 2008. He was reelected in 2012 and 2016 to four-year terms. In 2015, FFRF awarded Chambers its Emperor Has No Clothes Award.

“As an elected official, I know the difference between theology and politics. My interest is in legislation, not salvation.”

— Chambers, Hero of the First Amendment acceptance speech (Nov. 12, 2005)

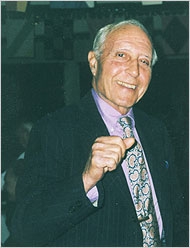

Vern Bullough

On this date in 1928, Vern Leroy Bullough was born in Salt Lake City, Utah. He earned a B.A. in history and languages from the University of Utah in 1951, an M.A. in history from the University of Chicago in 1951, a Ph.D. in the history of medicine and science from the University of Chicago in 1954 and a B.S. in nursing from California State University-Long Beach in 1981. Bullough was a sexologist and historian, as well as a professor of nursing, sociology and history. He was Dean of the Faculty of Natural and Social Sciences at State University of New York at Buffalo and was one of the founders of the Center for Sex Research at Cal State.

Bullough received numerous awards for his work, including the prestigious Kinsey Award in 1995. He was a strong supporter of civil liberties who worked with the ACLU and the NAACP. Bullough has published and edited numerous books, many co-written with his first wife, Bonnie Uckerman Bullough, who was also a nurse and sexologist. Their collaborations include The Subordinate Sex: A History of Attitudes Toward Women (1973) and Sexual Attitudes: Myths and Realities (1995).

Bullough was co-president of the International Humanist and Ethical Union from 1994-97 and its vice president in 1997-98. He received a Distinguished Humanist Service Award from the IHEU in 1992. Bullough was an honorary associate of the Indian Rationalist Association, and also worked with the Humanist Academy. He wrote the 1994 essay “Science, Humanism, and the New Enlightenment.”

He had married Bonnie, his high school sweetheart, in 1947. They had two sons (David, 1954, and James, 1956). They expanded their family through the adoption of Steven (1958), Susan (1961) and Michael (1966). James died tragically when hit by a car in 1967 in Egypt during Bonnie’s year as a Fulbright Scholar. She died in 1996. Bullough later married Gwen Baker. He died of cancer at age 77 in Westlake Village, Calif. (D. 2006)

PHOTO: Oviatt Library, CSU-Northridge

"[Vern Bullough] will be sorely missed as one of the leading secular humanists in North America and the world."

— Paul Kurtz, founder of the Center for Inquiry and Council for Secular Humanism, quoted on the IHEU website.

Lawrence Lader

On this date in 1919, Lawrence Lader was born in New York City. He graduated from Harvard University in 1941 and later served during World War II. Lader was a writer and journalist who worked for Reader’s Digest and The New Republic and wrote many books about abortion rights. His 1966 book Abortion was among the first major works published about the then-taboo subject. It was influential in the Roe v. Wade decision: The Supreme Court cited Abortion numerous times in its decision.

Lader co-founded the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (now NARAL Pro-Choice America). Lader’s other titles include The Margaret Sanger Story and the Fight for Birth Control (1955) and Bold Brahmins: New England’s War Against Slavery, 1831-63 (1973). He and his wife, Joan Summers Lader, had a daughter, Wendy.

According to Anne Nicol Gaylor, co-founder of FFRF who served with Lader on the NARAL board of directors, Lader was a freethinker. In 1987 he published Politics, Power, and the Church: The Catholic Crisis and Its Challenge to American Pluralism. Lader wrote, “The Catholic hierarchy still rejects pluralism when many of its moral beliefs and dogma are in dispute. Through legislation on divorce, school prayer, abortion, and a host of issues, it has sought to legalize its moral codes.”

Lader was awarded FFRF’s Freethought Pioneer Award in 1989 for his 1988–89 lawsuit against the Catholic Church, which asked for the church’s tax-exempt status to be removed because of its political lobbying. The lawsuit was lost on standing. He died of colon cancer in Manhattan at age 86. (D. 2006)

"Catholic power, allied with Fundamentalism, has threatened the American tenet of church-state separation and shaken the fragile balance of our pluralistic society."

— Lader, "Politics, Power and the Church" (1987)

Taslima Nasrin

On this date in 1962, freethinker, atheist and feminist Taslima Nasrin was born in Mymensing, Bangladesh, to a Sufi physician and a devoutly religious mother. Nasrin later became the target of a series of fatwas, or religious sanctions, condemning her to death for blasphemy.

“I came to suspect that the Quran was not written by Allah but, rather, by some selfish, greedy man who wanted only his own comfort,” Nasrin explained in her speech accepting a Freethought Heroine Award at the 25th annual FFRF convention in 2002. “So I stopped believing in Islam. When I studied other religions, I found they, too, oppressed women.” She has often stated, “Religion is the great oppressor, and should be abolished.”

Nasrin earned an MBBS degree in 1984 and worked in gynecology and anesthesiology departments in medical colleges and universities. Her books of poetry began being published in the late 1980s, then she started writing popular columns on women’s rights in newspapers and magazines, which were collected in book form. In 1992, she received the prestigious Indian literary award “Ananda” for her book of essays. Nasrin reports that Islamic fundamentalists started campaigns against her by 1990, with demonstrations escalating over the next few years, including having her books burned at the national book fair.

When the novella “Shame” came out in 1993, about the plight of Hindus under Muslim order, it was banned, she was attacked at the national book fair, the first of three fatwa was issued, and a bounty on her head was offered. The Bangladeshi government brought criminal charges against her for defaming the Muslim faith the following year. Thousands in Bangladesh demonstrated regularly, sometimes daily, demanding her death. After a terrifying two months in hiding, and fearing the fate of Hypatia, Nasrin fled Bangladesh, seeking refuge in Sweden.

In a 1994 interview with The New Yorker, she said, “I want a modern, civilized law where women are given equal rights. I want no religious law that discriminates, none, period — no Hindu law, no Christian law, no Islamic law. Why should a man be entitled to have four wives? Why should a son get two-thirds of his parents’ property when a daughter can inherit only a third?”

Nasrin, a “woman without a country,” has also lived in France, the U.S. and Germany, living, for the most part, in India.

Among the dozens of awards and honorary doctorates she has received is the Sakharov Prize (1994). In addition to receiving FFRF’s 2002 Freethought Heroine Award, she was the recipient in 2015 of its Emperor Has No Clothes Award and said, “Islam is not compatible with human rights, women’s rights, freedom of expression and democracy.” She has continued to lecture, speak out and write, including a multi-book autobiography.

PHOTO: Nasrin at FFRF’s national convention in 2015; Ingrid Laas photo.

“There has always been a marked conflict between religion and science, and every time science emerges as the winner, as science bases itself on facts, not faith. It supports what is tested and is true and truth cannot be hidden by lies for a very long time. To abolish all kinds of hypocrisy from my country, we need more atheists to speak the truth.”

— Nasrin, accepting the Emperor Has No Clothes award in 2015

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

On this date in 1815, freethinker and founding mother of the feminist movement Elizabeth Cady was born in Johnstown, N.Y. Avid to please her father, a judge and member of Congress, in the face of his bitter loss of all five sons, she excelled in academic studies and horseback riding. Barred as a young woman from college despite her lively intellect, she married anti-slavery agent Henry Stanton. Their 1840 honeymoon took them to the fateful World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London.

Her eyes were opened to women’s subjugation and religion’s role in keeping women subordinate after she and other female delegates were humiliatingly curtained off from debate at clergy instigation. At 32 the harried housewife and mother (eventually of seven) instigated and planned, with Lucretia Mott and three other women, the world’s first woman’s rights convention. The Seneca Falls convention met on July 19-20, 1848. Stanton’s “shocking” suffrage plank won endorsement and galvanized women for the next 72 years. She recalled later how “the Bible was hurled at us from every side” in a history of the early movement.

Stanton entered into a lifelong working partnership with Susan B. Anthony, founded and was first president of the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1869 and served as the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s controversial first president in 1890.

Stanton wrote the 19th Amendment, finally adopted in 1920, granting the vote to women. Nearly every speech she wrote condemned religious dogma. In her first letter to Anthony, she wrote, “The Church is a terrible engine of oppression, especially as concerns woman.” (April 2, 1852)

In her diary she recorded that her belief was “grounded on science, common sense, and love of humanity,” not “fears of the torments of hell and promises of the joys of heaven.” (Sept. 25, 1882) She dedicated her last years to freeing women from superstition, writing The Woman’s Bible (1895, 1898). In 1898 that book was officially repudiated by the very suffrage movement Stanton had help form. The last article she wrote before her death was “An Answer to Bishop Stevens,” urging people to “embrace truth as it is revealed today by human reason.” (D. 1902)

PHOTO: Stanton and her daughter Harriot in 1856.

"I have endeavoured to dissipate these religious superstitions from the minds of women, and base their faith on science and reason, where I found for myself at least that peace and comfort I could never find in the Bible and the church.”

“For fifty years the women of this nation have tried to dam up this deadly stream that poisons all their lives, but thus far they have lacked the insight or courage to follow it back to its source and there strike the blow at the fountain of all tyranny, religious superstition, priestly power, and the canon law."

— Stanton, "The Degraded Status of Woman in the Bible" (1896)

Stephen Symonds Foster

On this date in 1809, Stephen Symonds Foster was born in Canterbury, N.H. He graduated from Dartmouth College in 1838 and went on to enroll in Union Theological Seminary, where he became disheartened with the pro-slavery views of many churches. The principal of Union Theological Seminary offered Foster a bribe to stop discussing his position on slavery, but Foster declined and left the seminary after only a year.

He helped to organize the New Hampshire Young Men’s Anti-Slavery Society and was a member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, along with his wife, Abigail Kelley. Foster and Kelley were also strong supporters of women’s rights and the temperance movement. The family lived on a farm called Liberty Farm in Massachusetts, which they used to help slaves escape on the underground railroad.

Foster was an outspoken abolitionist who critiqued churches for their support of slavery, often interrupting services to rail against it. In 1844 he published the pamphlet “The Brotherhood of Thieves; or, a True Picture of the American Church and Clergy,” an exposé of the anti-abolitionist views of churches and the clergy. In the introduction he described it as a “testimony against the popular religion of our country.” (D. 1881)

“During the 1844 New England Antislavery Convention, Foster held up a collar and manacles and declared, ‘Behold here a specimen of the religion of this land, the handiwork of the American church and clergy.’ "

— "The Puritan Origins of American Patriotism" by George McKenna (2007)