November 25

Anne Nicol Gaylor

On this date in 1926, Freedom From Religion Foundation founder Anne Gaylor, née Nicol, was born on a farm near Tomah, Wis. Her mother, Lucie Sowle Nicol, who died when Gaylor was 2, was descended from George Sowle, a passenger on the Mayflower (an apprentice, not a pilgrim). On her father’s side she was a second-generation freethinker. Reading by age 4 and soon reading everything in her one-room school’s small library, she was grateful to freethinker Andrew Carnegie (who shares her birthday) for endowing the Tomah Public Library.

She graduated from high school at 16, worked for room and board and as a waitress to pay for college and graduated with an English degree from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1949. She married Paul Gaylor in 1949 and continued to work through four pregnancies. She sold her successful business in 1966, the first private employment agency in Madison, and became editor of the Middleton Times-Tribune, turning it into an award-winning weekly. After writing the first editorial in the state calling for legalized abortion in 1967, she began receiving calls from desperate women and turned to volunteer activism.

Gaylor founded the ZPG Abortion Referral Service in 1970. Over the next five years it made more than 20,000 referrals for birth control, abortion and sterilization. In 1972 she co-founded the Women’s Medical Fund to help low-income women pay for abortions. She ran that charity as a hands-on volunteer for more than 40 years, speaking individually with and helping coordinate financial care for more than 20,000 women, until retiring as administrator in March 2015 at age 88 after suffering several mini-strokes. “There were many groups working for women’s rights,” she realized, “but none of them dealt with the root cause of women’s oppression — religion.” Her book Abortion Is a Blessing was published in 1975.

In 1976 she founded the Freedom From Religion Foundation with her daughter Annie Laurie and Jon Sontarck of Milwaukee to promote freethought and the separation of state and church. After a string of successful legal and media actions, she was asked to go national with the foundation in 1978 and served as its elected president for 28 years. She took the foundation from a three-member, dining-room operation to a group with just over 30,000 members (in 2019), a national office, newspaper, other publications and many successful state/church lawsuits. She worked as a consultant from 2005 until her death. One of her most widely quoted aphorisms is “Nothing fails like prayer.”

Under her tutelage, FFRF won many court victories, including turning an initially failed 1980s challenge of a Ten Commandments monument in a city park in La Crosse, Wis., into a firm victory in 2004, and winning a Sixth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals ruling in a Dayton County, Tenn., case (“Scopes II”) affirming there should be no religious instruction in public schools. Legal highlights include Gaylor v. Reagan, a highly publicized suit against declaring 1983 to be “The Year of the Bible,” a litigation victory in 1996 declaring Wisconsin’s Good Friday holiday unconstitutional and making sparks fly in interviews and national media appearances, including “The Phil Donahue Show.” She authored Lead Us Not Into Penn Station, a short book of provocative essays.

Other notable accomplishments include being the first to call for the recall of Dane County Circuit Judge Archie Simonson when he termed rape a “normal reaction” in 1977. She wrote the official petition that resulted in a successful election removing him from office. In 1994 she and her daughter helped spearhead the rescue of Forward, a Jean Miner sculpture embodying the state motto first displayed at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, when then-Gov. Tommy Thompson proposed removing it from the State Capitol grounds. In 1989 the Women’s Medical Fund successfully sued state Attorney General Donald Hanaway, forcing him to remove Wisconsin from an amicus brief to the U.S. Supreme Court seeking to overturn Roe. v. Wade.

Her awards included 1994 Feminist of the Year from the Wisconsin chapter of the National Organization for Women, the 1985 Humanist Heroine Award in 1985 from the American Humanist Association and the Zero Population Growth Recognition Award in 1983. Paul Gaylor, her husband, FFRF’s chief volunteer, died in 2011. Their children are Andrew, twins Ian and Annie Laurie, and Jamie, and there are two granddaughters, Lily and Sabrina Gaylor.

She stepped down as president in 2004 but stayed involved in various other capacities. Go here for a tribute and an extensive history of FFRF with many photos and headlines through the years.

Gaylor died on June 14, 2015, two weeks after a serious fall in her independent living apartment fractured her skull. She directed that her tombstone in the Nicol family plot in Sparta read: “Feminist — Activist — Freethinker.” Read the press release announcing her death, which rated national coverage, including an obituary in The New York Times, and an outpouring of tributes. (D. 2015)

PHOTO: Anne Gaylor in 1975; photo by Paul J. Gaylor.

"There are no gods, no devils, no angels, no heaven or hell. There is only our natural world. Religion is but myth and superstition that hardens hearts and enslaves minds."

— Gaylor's wording to counter religious displays. It appears on FFRF's Winter Solstice sign at the Wisconsin Capitol every December.

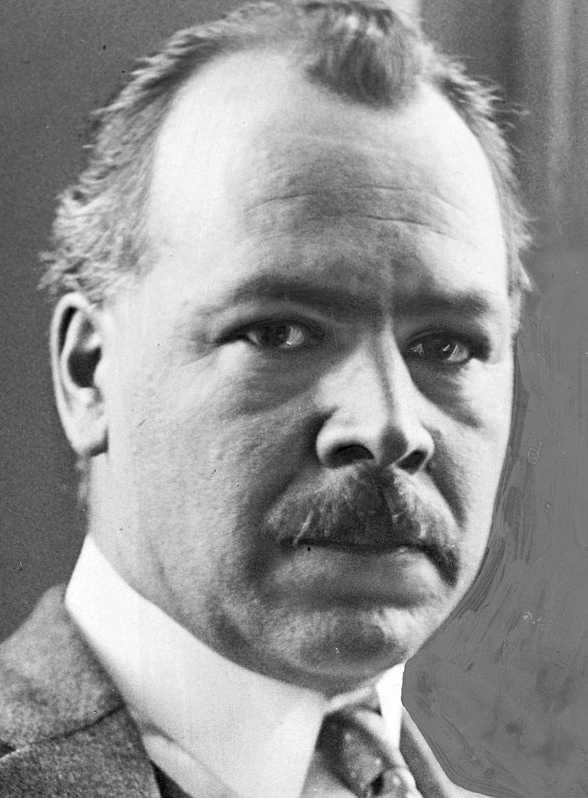

Andrew Carnegie

On this date in 1835, tycoon turned philanthropist Andrew Carnegie was born in Dumfermline, Scotland. In 1848 he traveled with his family to Allegheny, Pa. He entered the workforce at 13 as a bobbin boy in a cotton mill, worked at Western Union and the Pennsylvania Railroad, then founded the Keystone Bridge Works and the Union Iron Works in Pittsburgh. In his book The Gospel of Wealth (1899), he proposed that the rich are obligated to give away their fortunes.

He began his philanthropy in his 30s, first endowing his native town, and eventually establishing seven philanthropic and educational corporations. His principal desire was to promote free public libraries. When he started that campaign in 1881, they were scarce in the U.S. His $56 million built 2,509 libraries. By the time of his death he had given away more than $350 million.

Carnegie rejected Christianity and sectarianism and was delighted to replace those views with evolution: “Not only had I got rid of the theology and the supernatural, but I had found the truth of evolution,” he wrote in his 1920 autobiography, published the year after his death. After encountering missionaries on a voyage to the Pacific, Carnegie wrote humorously in his diary that he would “never forgive” the missionary for a particularly ridiculous sermon. When applied to for money by those same missionaries to China, Carnegie wrote them: “I think that money spent upon foreign missions for China is not only money misspent, but that we do a grievous wrong to the Chinese by trying to force our religion upon them against their wishes.” (Carnegie to Ella J. Newton, Foochow, China, Nov. 26, 1895)

His attitude toward religion softened later in life when he attended a Presbyterian church pastored by Social Gospel exponent Henry Sloane Coffin and had a brief correspondence with the eldest son of the founder of the Bahá’í faith.

He did not want to marry during his mother’s lifetime. After she died in 1886, the 51-year-old Carnegie married Louise Whitfield, 21 years his junior. They had their only child in 1897, a daughter named after his mother Margaret. He died at age 83 of bronchial pneumonia at his estate in Lenox, Mass. (D. 1919)

"The whole scheme of Christian Salvation is diabolical as revealed by the creeds. An angry God, imagine such a creator of the universe. Angry at what he knew was coming and was himself responsible for. Then he sets himself about to beget a son, in order that the child should beg him to forgive the Sinner. This however he cannot or will not do. He must punish somebody — so the son offers himself up & our creator punishes the innocent youth, never heard of before — for the guilty and became reconciled to us. … I decline to accept Salvation from such a fiend."

— 1905 Carnegie letter to Sir James Donaldson of St. Andrews University, cited by Joseph Frazier Wall in "Andrew Carnegie" (1970)

Nikolai Vavilov

On this date in 1887, Russian geneticist and agronomist Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov was born to a merchant family of modest means in Moscow. His older brother Sergey would become a renowned physicist.

He graduated from the Moscow Agricultural Institute in 1910, then worked at the Bureau for Applied Botany and the Bureau of Mycology and Phytopathology. In 1913-14 he traveled in Europe and studied plant immunity with British biologist William Bateson, who helped establish the science of genetics.

From 1917-20 he was an agronomy professor at the University of Saratov. His son Oleg (with his first wife Yekaterina Sakharova) was born in 1918. From 1924-35 he directed the Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Leningrad. His marriage ended in divorce in 1926, after which he married geneticist Elena Ivanovna Barulina. Their son Yuri was born in 1928.

While developing his theory on the origin of cultivated plants, Vavilov organized a series of expeditions that eventually collected over 250,000 seeds and roots from around the world and were stored in Leningrad. His work ran counter to that of Trofim Lysenko, whose anti-Mendelian concepts of plant biology had won favor with dictator Joseph Stalin. Lysenko’s ascent was due to his promise of quick crop improvement compared to Vavilov’s slower process of hybridization, testing and selection.

Vavilov refused to follow the politically expedient path and was arrested in 1940 and sentenced to death in July 1941, though the sentence was later reduced to 20 years in prison, where he died in 1943 at age 55. The death certificate listed “decline of cardiac activity” but some authors asserted the actual cause of death was starvation.

He was posthumously pardoned by Nikita Khrushchev during de-Stalinization, when his reputation was publicly rehabilitated and he began to be hailed as a hero of Soviet science. In 1993, the 50th anniversary of his death, James F. Crow, an evolutionary biologist and population geneticist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, wrote an article titled “N.I. Vavilov, Martyr to Genetic Truth” in the journal of the Genetics Society of America.

Crow wrote: “Vavilov was a strong believer in the importance of selection, both for evolution and as a tool for the plant breeder. Finding diverse types, hybridizing them, and especially selecting among the recombinants, gave the best hope for producing better plants. And, of course, he was right. But the slow and certain program he was advocating could not compete in the political arena with those who promised instant gratification. Here lies a lesson for all science.”

In 2020, National Geographic’s “Cosmos: Possible Worlds” featured an episode on Vavilov. (D. 1943)

“Despite his strict upbringing in the Orthodox Church, Vavilov had been an atheist from an early age. If he worshipped anything, it was science.”

— "The Murder of Nikolai Vavilov: The Story of Stalin's Persecution of One of the Great Scientists of the Twentieth Century" by Peter Pringle (2008)