civil-rights-activists

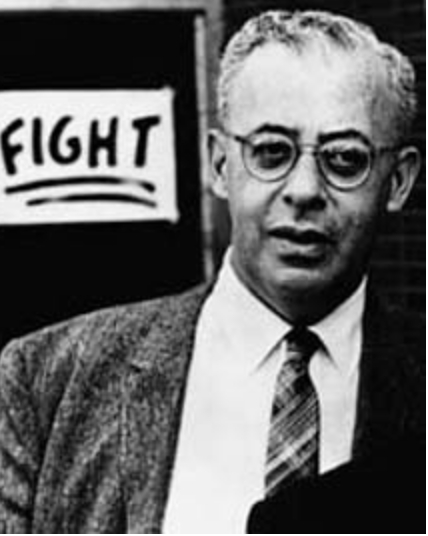

Saul Alinsky

On this date in 1909, community organizer Saul David Alinsky was born in a Chicago slum to Russian-Jewish immigrant parents. Alinsky said in an interview that they “were strict Orthodox; their whole life revolved around work and synagogue.” When asked if he was devout as a boy, he responded, “I suppose I was — until I was about 12. I was brainwashed, really hooked. But then I got afraid my folks were going to try to turn me into a rabbi, so I went through some pretty rapid withdrawal symptoms and kicked the habit.” (Playboy, 1972)

Alinsky majored in archaeology at the University of Chicago, but after two years of graduate study he left to work as a criminologist for the state of Illinois. In the mid-1930s, he started working with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and became a close friend of John L. Lewis. Alinsky shifted from labor to community organizing in 1939, focusing first on improving the impoverished slums he grew up in. In 1940, millionaire Marshall Field III provided him with funds to start the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF), which grew into a prominent training institute for radical community organizers across the country.

Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez were connected to the IAF, along with numerous other organizers and movements. Alinsky’s “street-smart tactics influenced generations of community organizers,” including President Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, who wrote her senior honors thesis at Wellesley College on Alinsky (New York Times, Aug. 22, 2009). The Times said Alinsky was “hated and feared in high places from coast to coast” for being “a major force in the revolution of powerless people.”

His political philosophy was very nonconformist, and this carried over into his personal life. When asked if he had ever considered joining the Communist Party, he told Playboy, “Not at any time. I’ve never joined any organization — not even ones I’ve organized myself. I prize my own independence too much. And philosophically I could never accept any rigid dogma or ideology, whether it’s Christianity or Marxism.” The goal of the radical, Alinsky explained in his last book, Rules for Radicals (1971), must be to bring about “the destruction of the roots of all fears, frustrations, and insecurity of man, whether they be material or spiritual.” Enemies of the poor “can no more live up to their own rules than the Christian church can live up to Christianity.”

In a move that horrified the Religious Right, Alinsky dedicated the book to the devil: “the first radical known to man who rebelled against the establishment and did it so effectively that he at least won his own kingdom — Lucifer.” His first book, published in 1946, was Reveille for Radicals. Three years later he published John L. Lewis: An Unauthorized Biography.

Alinsky married Helene Simon, another University of Chicago student, and they adopted two children, Kathryn and Lee David. Helen tragically drowned in 1947. He was married to Jean Graham from 1952 until their divorce in 1970. The next year he married Irene McInnis. He died of a heart attack in 1972 at age 63 while walking in Carmel, Calif. His ashes were buried in a family plot in Chicago. On the marker is a quote from Thomas Paine that also appears in the epigraph of Rules for Radicals: “Let them call me rebel and welcome, I feel no concern from it; but I should suffer the misery of devils, were I to make a whore of my soul.” (D. 1972)

PHOTO: Alinsky in 1963; photo by Pierre869856, CC 4.0.

“If you think you’ve got an inside track to absolute truth, you become doctrinaire, humorless and intellectually constipated. The greatest crimes in history have been perpetrated by such religious and political and racial fanatics.”

— Alinsky, 1972 interview with Playboy magazine

Flo Kennedy

On this date in 1916, lawyer, activist, civil rights advocate and feminist Florynce Rae “Flo” Kennedy was born in Kansas City, Mo., to parents Wiley and Zella Kennedy. The second of five daughters, Kennedy grew up in a mostly white neighborhood, in which her father once stood up to members of the Ku Klux Klan with a shotgun. Kennedy wrote, “My parents gave us a fantastic sense of security and worth. By the time the bigots got around to telling us that we were nobody, we already knew we were somebody.”

Finishing high school at the top of her class in 1934, Kennedy opened a hat shop, performed on a radio show and operated an elevator. Her first political protest involved helping to organize a boycott when the local Coca-Cola bottler refused to hire black truck drivers. She moved to New York in 1942, graduating from Columbia University in 1948. In 1951 she became the first black woman to graduate from Columbia Law School, where she was admitted after threatening legal action on the grounds of racial discrimination.

Kennedy ran her own law practice, representing the estates of jazz greats Billy Holiday and Charlie Parker and the black power leader H. Rap Brown, among other Black Panthers. Despite tending to take on cases related to feminism and civil rights, Kennedy eventually realized that she needed to employ broader strokes to battle oppression and effect the kind of social change she had in mind. Turning to political activism, Kennedy cofounded the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966. That same year, she established the Media Workshop in an effort to influence the representation of black people in journalism and advertising, threatening boycotts and pickets.

At a 1967 anti-Vietnam War convention in Montreal, her speaking career was launched by a fiery invective against the refusal to allow Bobby Seale to discuss racism. Kennedy became known for her vitriolic tirades and incendiary comments, delivered in her characteristic cowboy hat and boots.

Along with feminism and racial equality, Kennedy also championed gay rights, as well as rights for prostitutes and other minorities. In 1971, Kennedy founded the Feminist Party, nominating Shirley Chisholm, a New York Democrat, for president, and helped to found the National Women’s Political Caucus. She founded the National Black Feminist Organization in 1975. Throughout her life, Kennedy championed pro-choice legislation, organizing a group of feminist lawyers to challenge New York State’s abortion law in 1969, influencing the legislature to liberalize abortion the next year.

With Diane Schulder, she coauthored a book called Abortion Rap in 1971. While Gloria Steinem is often unwittingly credited with the clever slogan, “If men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament,” Flo coined it. The two were warm colleagues, once going on a speaking tour together.

Kennedy was known for her quick repartee. When asked by a male heckler, “Are you a lesbian?” she replied, “Are you my alternative?” Kennedy launched a suit against the Catholic Church in 1968 for spending money illegally to influence abortion legislation, arguing that its campaign violated the separation of state and church. Furthering her efforts to rescind the church’s tax-exempt status in 1972, Kennedy filed tax evasion charges against the church with the IRS. She was briefly married to Charles Dudley Dye in 1957 but he died soon after. D. 2000.

“If men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament.”

— Flo Kennedy, who, with Gloria Steinem, popularized this iconic slogan, repeating a remark made to them both by a woman taxi-cab driver in Boston.

W.E.B. Du Bois

On this date in 1868, W.E.B. Du Bois (William Edward Burghardt) was born in Great Barrington, Mass. He attended all-black Fisk College in Nashville, then earned his B.A. in 1890 and his M.S. in 1891 from Harvard. Du Bois studied at the University of Berlin on a fellowship. Returning from Europe, he completed his graduate studies in history and in 1895 was the first African-American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard. He taught economics and history at Atlanta University from 1897-1910. The Souls of Black Folk (1903) made his name, in which he urged black Americans to stand up for their educational and economic rights.

Du Bois was a founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and edited the NAACP’s official journal, The Crisis, from 1910-34. He turned The Crisis into the foremost black literary journal. He expanded his interests to global concerns and is called the “father of Pan-Africanism” for organizing international black congresses.

Although he used some religious metaphor and expressions in some of his writing, Du Bois called himself a freethinker (see quote below). In “On Christianity,” a posthumously published essay, Du Bois critiqued the black church: “The theology of the average colored church is basing itself far too much upon ‘Hell and Damnation’ — upon an attempt to scare people into being decent and threatening them with the terrors of death and punishment. We are still trained to believe a good deal that is simply childish in theology. The outward and visible punishment of every wrong deed that men do, the repeated declaration that anything can be gotten by anyone at any time by prayer.”

Du Bois married Nina Gomer, with whom he had two children. As a widower he married Shirley Graham. At age 93, he and his wife traveled to Ghana to take up residence and start work on an encyclopedia of the African diaspora. In early 1963 the U.S. refused to renew his passport because of his Communist Party ties, so he made the symbolic gesture of becoming a citizen of Ghana, where he died two years later in the capital Accra at age 95. (D. 1963)

"My ‘morals’ were sound, even a bit puritanic, but when a hidebound old deacon inveighed against dancing I rebelled. By the time of graduation I was still a ‘believer’ in orthodox religion, but had strong questions which were encouraged at Harvard. In Germany I became a freethinker and when I came to teach at an orthodox Methodist Negro school I was soon regarded with suspicion, especially when I refused to lead the students in public prayer. When I became head of a department at Atlanta, the engagement was held up because again I balked at leading in prayer. … I flatly refused again to join any church or sign any church creed. From my 30th year on I have increasingly regarded the church as an institution which defended such evils as slavery, color caste, exploitation of labor and war. I think the greatest gift of the Soviet Union to modern civilization was the dethronement of the clergy and the refusal to let religion be taught in the public schools."

— W.E.B. Du Bois, "African-American Humanism: An Anthology," edited by Norm R. Allen Jr. (1968)

Corliss Lamont

On this date in 1902, Corliss Lamont was born in Englewood, N.J. His father, Thomas W. Lamont, was a chairman of J.P. Morgan & Co. He attended Phillips Exeter Academy and received his bachelor’s degree from Harvard University in 1924. He went on to obtain his Ph.D. in philosophy from Columbia University in 1932. Lamont supported many radical causes, including socialism, and although he never joined the Communist Party, he was strongly opposed to the persecution of communists.

He served as the director of the the American Civil Liberties Union from 1932 until 1954. He was a founder in 1954 of the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee. After being called before the House Un-American Activities Committee because of a book he had written, The Peoples of the Soviet Union (1946), he was cited for contempt of Congress. The indictment was dismissed by the Court of Appeals on the grounds that he was outside the jurisdiction of the committee.

Lamont wrote many books, pamphlets and essays, including many on humanism. His influential book The Philosophy of Humanism (1949), was based on a course he taught at Columbia in the 1940s and 1950s on naturalistic humanism. Other books on humanist subjects include his classic The Illusion of Immortality (1935), which argued against the imortality of the soul. He also wrote A Humanist Funeral Service (1954) and A Humanist Wedding Service (1970).

He was an active member for many years of the American Humanist Association and in 1977 received its Humanist of the Year award. He died of heart failure at age 93 in 1995.

"The greatest difference between the Humanist ethic and that of Christianity and the traditional religions is that it is entirely based on happiness in this one and only life and not concerned with a realm of supernatural immortality and the glory of God. Humanism denies the philosophical and psychological dualism of soul and body and contends that a human being is a oneness of mind, personality, and physical organism. Christian insistence on the resurrection of the body and personal immortality has often cut the nerve of effective action here and now, and has led to the neglect of present human welfare and happiness."

— Lamont, "The Affirmative Ethics of Humanism," The Humanist (March/April 1980)

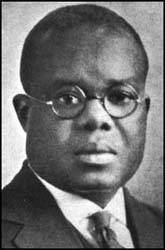

A. Philip Randolph

On this date in 1889, labor organizer, civil rights activist and journal editor Asa Philip Randolph was born in Crescent City, Florida, to parents James and Elizabeth (Robinson) Randolph. Growing up in Jacksonville, Randolph’s intellectual curiosity was shaped by his father, who, though a Methodist minister, encouraged him and his brother James to read freethought works. Through fireside debates about the existence of God with James and father, Randolph found that no logical conclusion of the affirmative or negative could be reached.

After high school he held a series of jobs, but facing discrimination, moved to New York City in 1911 to pursue an acting career, helping to establish the Shakespeare Society in Harlem and playing several title roles. When his parents disapproved of his acting career, Randolph enrolled at City College of New York in 1911, studying literature and sociology. Although he did not complete his degree, his political philosophy influenced his civil rights activism. Randolph believed that the root of racism was economic inequality. He began public speaking and founded the radical black magazine The Messenger in 1917.

Randolph went on to organize a union of New York City elevator operators and Virginia shipyard workers as president of the National Brotherhood of Workers of America. One of his greatest achievements was organizing the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) in 1925, which became the nation’s first all-black union. The U.S. government named him one of the “most dangerous Negroes” in America as a result of his outspokenness. Traveling around the country to establish new union chapters, Randolph became a skilled orator, speaking out to end Pullman Company’s unfair treatment of black railroad employees.

In 1941, Randolph planned a march on Washington to protest employment discrimination and segregation of the armed forces. Though the march wasn’t held, it helped spur passage of the Fair Employment Act. When President Truman called for a peacetime draft in 1947, Randolph continued to pioneer nonviolent civil disobedience, again threatening a march on Washington. This led to an executive order, which finally ended racial segregation in the U.S. military.

In the 1950s he allied with Martin Luther King Jr. With MLK’s assistance in 1957, Randolph orchestrated a prayer pilgrimage to Washington to peacefully demand that Southern schools comply with the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision ordering school integration. Randolph was a chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. An event typically considered the pinnacle of the civil rights movement, the march was attended by 250,000 people. It created momentum leading to passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

At age 74 he introduced MLK’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech, saying of the event, “This is the most beautiful day of my life.” (A. Philip Randolph: A Biographical Portrait by Jervis Anderson.) In 1964 he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Soon after, he founded the A. Philip Randolph Institute to study and ameliorate the causes of poverty, appearing at the White House in 1966 to propose a solution he termed the “Freedom Budget.”

Although he recognized the power of using religious rhetoric to motivate people to take action, Randolph’s secular humanist philosophy rankled some leaders of the civil rights movement. The American Humanist Association named him Humanist of the Year in 1970. He signed a public declaration of humanist principles, the Humanist Manifesto II, in 1973. Randolph married Lucille Campbell Green in 1913. (D. 1979)

"Prayer is not one of our remedies; it depends on what one is praying for. We consider prayer nothing more than a fervent wish; consequently the merit and worth of a prayer depend upon what the fervent wish is."

— Randolph, from the mission statement of his magazine, The Messenger

Hubert Harrison

On this date in 1883, Hubert Henry Harrison was born in St. Croix, in the Danish West Indies (now the U.S. Virgin Islands). After his mother’s death, Harrison left the West Indies for New York in 1900, where he earned a high school degree. From 1911 to 1914, he was active in the Socialist Party and, as perhaps its most prominent black member, he founded the Colored Socialist Club. Harrison was active in radical causes, as well as the fight for racial equality.

He eventually left the Socialists due to the movement’s support of segregated local chapters in the South. He formed several black radical groups, the Liberty League in 1917 and the International Colored Unity League in 1924. Harrison’s intellectual influence was widely felt in the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s, where he was known as the Black Socrates, as well as the father of Harlem radicalism.

Harrison stated that his own doubts about religion were prompted by a reading of Thomas Paine. After he stopped believing in the bible, he was briefly a deist, before finally becoming an agnostic. Though he found Catholic ceremonies attractive and believed in the spiritual part of the human experience, he said in his essay “Paine’s Place” (1911): “I doubt whether I will ever be anything but an honest Agnostic, because I prefer, as I once told you, to go to the grave with my eyes open.” (Quoted in Doubt: A History by Jennifer Michael Hecht, 2003)

“The Negro Conservative: Christianity Still Enslaves the Minds of Those Whose Bodies It Has Long Held Bound,” a 1914 article on atheism, discussed the paradox that African-Americans were largely religious despite the American church’s support for slavery and, later, institutionalized racism. According to Harrison, at the start of the Harlem Renaissance in the early 1920s, atheism, agnosticism and other forms of radicalism were becoming more common in black Harlem.

He died at age 44 in Bellevue Hospital in New York of complications from an appendectomy. (D. 1927)

"It should seem that Negroes, of all Americans, would be found in the Free-thought fold, since they have suffered more than any other class of Americans from the dubious blessings of Christianity."

— Harrison, "The Negro Conservative" (1914), quoted in "Doubt: A History" by Jennifer Michael Hecht ( 2003)

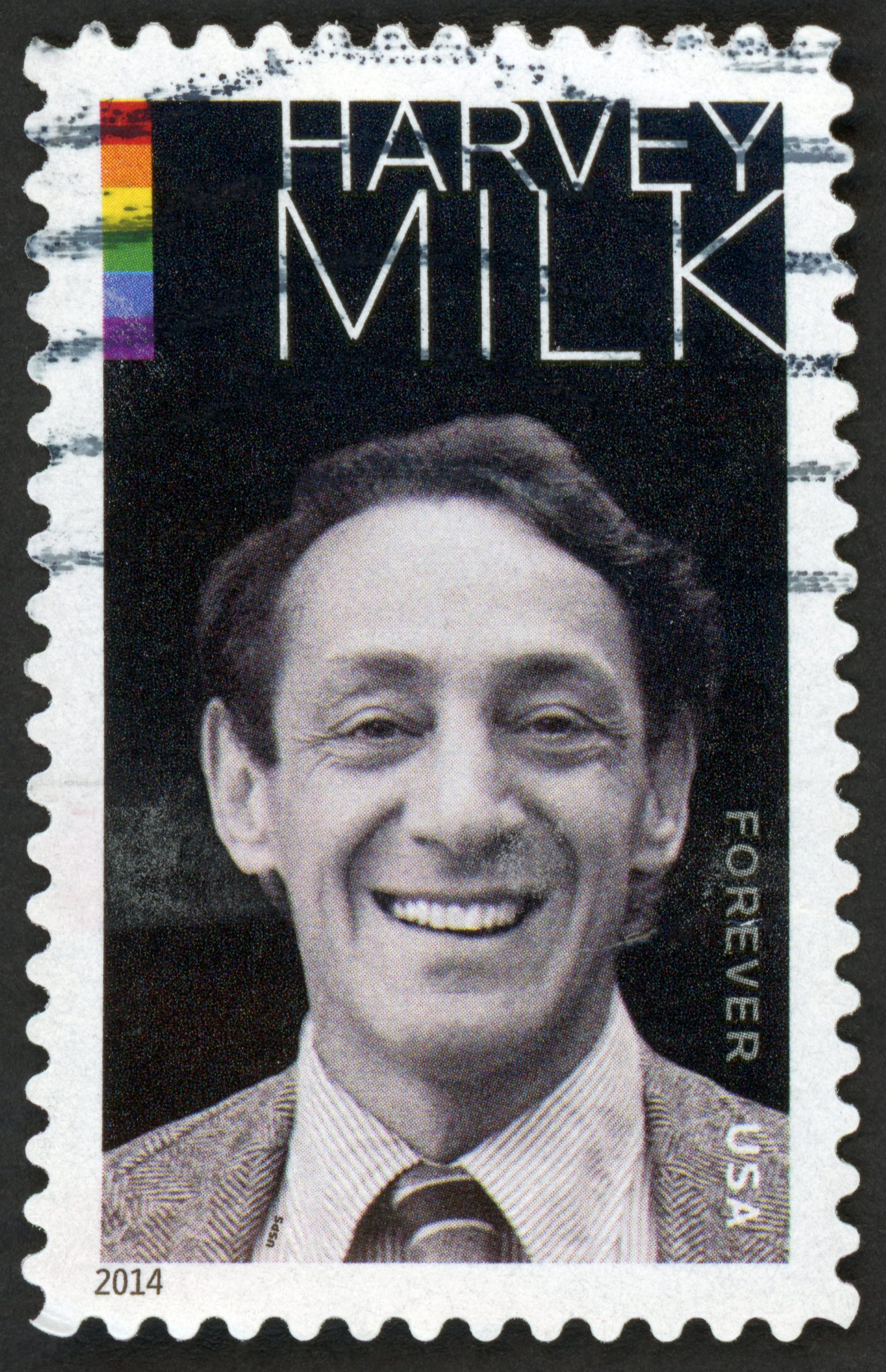

Harvey Milk

On this date in 1930, openly gay politician Harvey Milk was born in Woodmere, New York. He attended school at New York State College for Teachers in Albany, where he studied math and history. After being discharged from the U.S. Navy in 1955, Harvey spent subsequent years hiding his sexuality from his family and his work. During this time he was employed as a public school teacher, a stock analyst and a production assistant for Broadway musicals. Milk didn’t become active in politics until age 40 when he moved to San Francisco.

There he opened a camera shop on Castro Street in the center of the city’s growing gay community. In 1975 he narrowly lost his second race as a candidate for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. In 1977 he easily won a third bid. During the peak of his political career, Milk supported anti-discrimination bills, established day care centers for working mothers, converted military facilities into low-cost housing and spoke out on state and national issues for LGBT people, women, racial and ethnic minorities and other marginalized communities.

Harvey was assassinated in 1978 along with Mayor George Moscone by former city supervisor Dan White, a rabid opponent of gay rights. White was sentenced to only seven years and eight months in prison after being found guilty of voluntary manslaughter and not murder. After serving five years, he was released in 1984. He committed suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning in 1985.

Milk was very critical of organized religion and did not attend religious services. Randy Shilts wrote in The Mayor of Castro Street (2008) that “Harvey never had any use for organized religion.” In one of his recorded wills, Milk said of his funeral: “I hope there are no religious services. I would hope that there are no services of any kind, but I know some people are into that and you can’t prevent it from happening, but my god, nothing religious.” In 2008 Sean Penn starred in the biographical film “Milk.”

He was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and was inducted in the California Hall of Fame, with May 22 designated as Harvey Milk Day. (D. 1978)

“About six months ago, Anita Bryant in her speaking to God said that the drought in California was because of the gay people. On November 9, the day after I got elected, it started to rain. On the day I got sworn in, we walked to City Hall and it was kinda nice, and as soon as I said ‘I do,’ it started to rain again. It’s been raining since then and the people of San Francisco figure the only way to stop it is to do a recall petition.”

— Milk keynote speech in San Diego to the gay caucus of the California Democratic Council (March 10, 1978)

Harvey Fierstein

On this date in 1952, actor, comedian, playwright and LGBT activist Harvey Forbes Fierstein was born in Brooklyn, N.Y. He debuted in the Andy Warhol play “Pork” in 1971. He has since been in over 60 off-off-Broadway plays, including his own productions. One of his three-act plays, “The Torch Song Trilogy,” in which he played a gay man, opened off-off-Broadway in 1980, transferred to Broadway and won Fierstein two Tony Awards, an Obie, a Dramatist Guild Award, two Drama Desk Awards and a nomination for the prestigious Laurence Olivier Award.

The hugely successful play was made into a movie in 1988, with Fierstein writing the screenplay and co-starring with Matthew Broderick and Anne Bancroft. He earned his third Tony for his book of the musical “La Cage aux Folles.” He picked up a fourth Tony for his portrayal of Edna Turnblad in the Broadway version of “Hairspray” (2003).

In addition to his theater work, Fierstein is a popular face (and voice) in films, including such hits as “Mrs. Doubtfire” (1993), “Bullets Over Broadway” (1994), “Independence Day” (1996), “Death to Smoochy” (2002) and “Duplex” (2003), which starred Ben Stiller and Drew Barrymore. His trademark voice has lent its popularity to TV shows like “The Simpsons,” “How I Met Your Mother” and “Family Guy” and animated movies such as Disney’s “Mulan” (1998), “Kingdom Hearts II” (2005) and “Farce of the Penguins” (2006). He won an Emmy for narrating the documentary “The Times of Harvey Milk” (1984).

Fierstein is a leading gay rights activist and has consistently made his views on religion known. In an interview about playing Tevye in the Broadway revival of “Fiddler on the Roof,” when asked if he was generally religious, Fierstein said: “No, but I am Jewish. … I don’t believe in God, I don’t believe in heaven or hell.”

In a 2022 People magazine interview, Fierstein stated, “I’m still confused as to whether I’m a man or a woman,” and said that as a child he often wondered if he’d been born in the wrong body. “When I was a kid, I was attracted to men. I didn’t feel like a boy was supposed to feel. Then I found out about gay. So that was enough for me for then.”

PHOTO: by David Shinbone photo under CC 3.0.

“We are lucky enough to be living in a country that not only guarantees the freedom to practice religion as we see fit, but also freedom FROM religious zealots who would persecute and prosecute and even physically harm those of us who do not believe as they do. … Predicating patriotism on a citizen’s belief in God is as anti-American as judging him on the color of his skin. It is wrong. It is useless. It is unconstitutional.”

— Fierstein, "In the Life" broadcast by Generation Q (November 2004)

Civil Rights Act Enacted

On this date in 1964, the Civil Rights Act was signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson after it passed the Senate by a vote of 73–27 and the House by 289–126. It barred discrimination based on race, religion, color or national origin.

“An act to enforce the constitutional right to vote, to confer jurisdiction upon the district courts of the United States of America to provide injunctive relief against discrimination in public accommodations…”

—

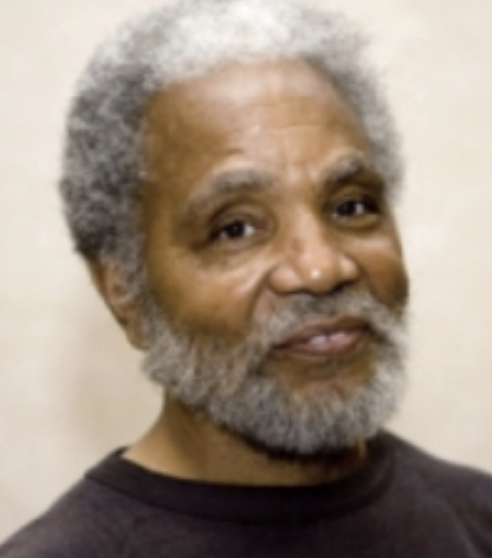

Ernie Chambers

On this date in 1937, politician Ernest Chambers, known as “the Maverick of Omaha” and “defender of the downtrodden,” was born in Omaha, Neb. Chambers understood early on the power of protest and of grassroots organizing, standing up for civil rights as a youth and emerging as a leader of African-American youths in Omaha. He graduated from Creighton University School of Law and was first elected to the unicameral legislature as a state senator in 1970, the only black member of the legislature in an overwhelmingly white, ultraconservative state.

Chambers became known for defending the rights of women, gays and lesbians and people of color. He challenged legislative prayers in the 1983 Supreme Court case Marsh v. Chambers, and although the court ruled against him, Chambers was successful in subsequently persuading the Senate to drop payment for prayers.

Rita Swan of Children’s Healthcare is a Legal Duty (CHILD) said in 2005, “Nebraska is the only state in the country that has never had a religious exemption to child neglect in either the juvenile or criminal codes and that distinction is due to Ernie’s forceful opposition and vigilance. Nebraska is one of four states without a religious exemption to metabolic screening of newborns and that again is because of Ernie’s leadership.” CHILD presented Chambers with its child advocacy service award for successfully arguing that “no parent should have a religious right to deprive a child of necessary health care” and keeping a religious exemption to health care from being enacted in that state.

Chambers cleverly filed a lawsuit in 2007 (Chambers v. God) to make a point about frivolous lawsuits. Chambers, who identifies as nonreligious without using a label, sought a permanent injunction against the defendant for making terroristic threats against him and his constituents, of inspiring fear and causing “widespread death, destruction and terrorization of millions upon millions of the Earth’s inhabitants.” In October 2008 the judge threw out his lawsuit, whimsically ruling that the defendant wasn’t properly served due to his unlisted home address.

Chambers, accepting FFRF’s Hero of the First Amendment Award in 2005, commented, “What I would do, from time to time, is mock, taunt, and ridicule my colleagues for injecting religion and Jesus into the legislature.” His political opponents, in a successful effort to finally unseat him from the Senate when they could not do so electorally, passed a law in 2000 establishing term limits so he was unable to seek reelection in 2008. He was reelected in 2012 and 2016 to four-year terms. In 2015, FFRF awarded Chambers its Emperor Has No Clothes Award.

“As an elected official, I know the difference between theology and politics. My interest is in legislation, not salvation.”

— Chambers, Hero of the First Amendment acceptance speech (Nov. 12, 2005)

Jessica Mitford

On this date in 1917, “Queen of the Muckrakers” Jessica Lucy Freeman-Mitford, nicknamed Decca, was born to a markedly eccentric, religious, aristocratic family in England. Her parents were anti-Semites and notorious members of the British Union of Fascists. Two of her sisters became high-profile fascists, but by age 14 Jessica was a pacifist. Like her sister Nancy, who became a novelist (Love in a Cold Climate), Jessica also embraced a left-wing socialism. She eloped in 1937 at age 19 to marry journalist Esmond Romilly, Winston Churchill’s nephew.

They honeymooned in Spain while he wrote about his experiences in the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. Romilly joined the Royal Canadian Air Force during World War II and was killed at age 23 in 1941 during a raid over Nazi Germany. Mitford then married radical lawyer Robert Treuhaft in 1943 and was active in civil rights campaigns. She led the “White Women’s Delegation” to Mississippi seeking to save a black defendant from the death penalty. She and her husband, who were members of the American Communist Party until 1958, refused to give evidence when summoned before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

She wrote the irreverent best-seller The American Way of Death (1963) after her husband became aware of outrageous funeral costs borne by working-class families. The book enraged funeral directors and the clergy and brought government regulation to the industry. It also spurred demand for cremation. She also wrote an autobiography, Daughters and Rebels (1960), The Trial of Dr. Spock (1970), A Fine Old Conflict (1977), Kind and Unusual Punishment: The Prison Business (1973), Poison Penmanship: The Making of a Muckraker (1979) and An American Way of Birth, (1992).

Mitford died at age 78 of cancer. After a $475 cremation, a memorial service was held in San Francisco, where famous speakers lauded her mordant sense of humor and lifelong unorthodoxy. (D. 1996)

PHOTO: Mitford in 1937.

“Openness about the more shadowy corners of experience was one of the many things, along with psychiatry and religion, that Decca simply didn't ‘go in for.’ "

— "Black Sheep," book review at slate.com of "Decca: The Letters of Jessica Mitford," ed. Peter Sussman (2006)