June 2

Barbara Smoker

On this date in 1923, Barbara Smoker was born in Great Britain. Such a devout Roman Catholic that she considered becoming a nun, Smoker renounced religious faith at age 26 and became a secular humanist activist instead. She served as president of the National Secular Society (NSS), the most militant of the British secular groups, from 1971-96. Her script “Why I Am an Atheist” was recorded for the BBC in 1985. She fought a statutory ban on embryo research with a pamphlet, “Eggs Are Not People,” distributed to all members of Parliament in 1985.

In the tradition of 19th-century secular activists Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant, Smoker officiated at more than 400 humanist funerals, as well as at weddings and analogous ceremonies on behalf of the Gay and Lesbian Humanist Association, which she co-founded. Smoker served as chair of the Voluntary Euthanasia Society from 1981-85, editing Voluntary Euthanasia: Experts Debate the Right to Die (1986).

When Muslims held a London demonstration in May 1989 against Salman Rushdie, Smoker, holding a banner reading “Free Speech,” was attacked by a surge of demonstrators and was rescued by a police officer.

Smoker remained active in the NSS for the rest of her life. In 2019 she published her autobiography “My Godforsaken Life: Memoir of a Maverick.” She also received a lifetime achievement award from the NSS in 2019.Smoker remained active in the NSS for the rest of her life. In 2019 she published her autobiography “My Godforsaken Life: Memoir of a Maverick.” She also received a lifetime achievement award from the NSS in 2019.

She died at Lewisham Hospital at age 96. (D. 2020)

“People who believe in a divine creator, trying to live their lives in obedience to his supposed wishes and in expectation of a supposed eternal reward, are victims of the greatest confidence trick of all time.”

— Smoker, "So You Believe in God!" (1974 pamphlet)

Edward Elgar

On this date in 1857, British composer Edward Elgar was born in England. Raised as a believing Roman Catholic, he discarded his faith toward the end of his life. Most of his earlier works were religious in nature, such as “The Apostles” and “The Kingdom,” intended to be part of a trilogy, which Elgar never finished. “Pomp and Circumstance” is one of his famous compositions.

Biographer Byron Adams wrote, “Paradoxically, the excursion into biblical exegesis that Elgar did during the creation of ‘The Apostles’ and ‘The Kingdom’ could have played a part in the unraveling of the composer’s already frayed beliefs.”

When Elgar was unconscious due to heavy doses of morphine for cancer pain, his daughter summoned a priest. His biographer writes, “Elgar died on 23 February 1934 and was buried next to his wife in the cemetery of St. Wulstan’s Roman Catholic Church in Little Malvern.” He had requested cremation and that his ashes be scattered, which conflicted with Catholic doctrine. (D. 1934)

“Elgar told me that he had no faith whatever in an afterlife: ‘I believe there is nothing but complete oblivion.’ ”

— Arthur Thomson, the doctor who delivered Elgar's fatal cancer diagnosis. "Elgar's Later Oratorios" by Byron Adams (included in "The Cambridge Companion to Elgar," 2004)

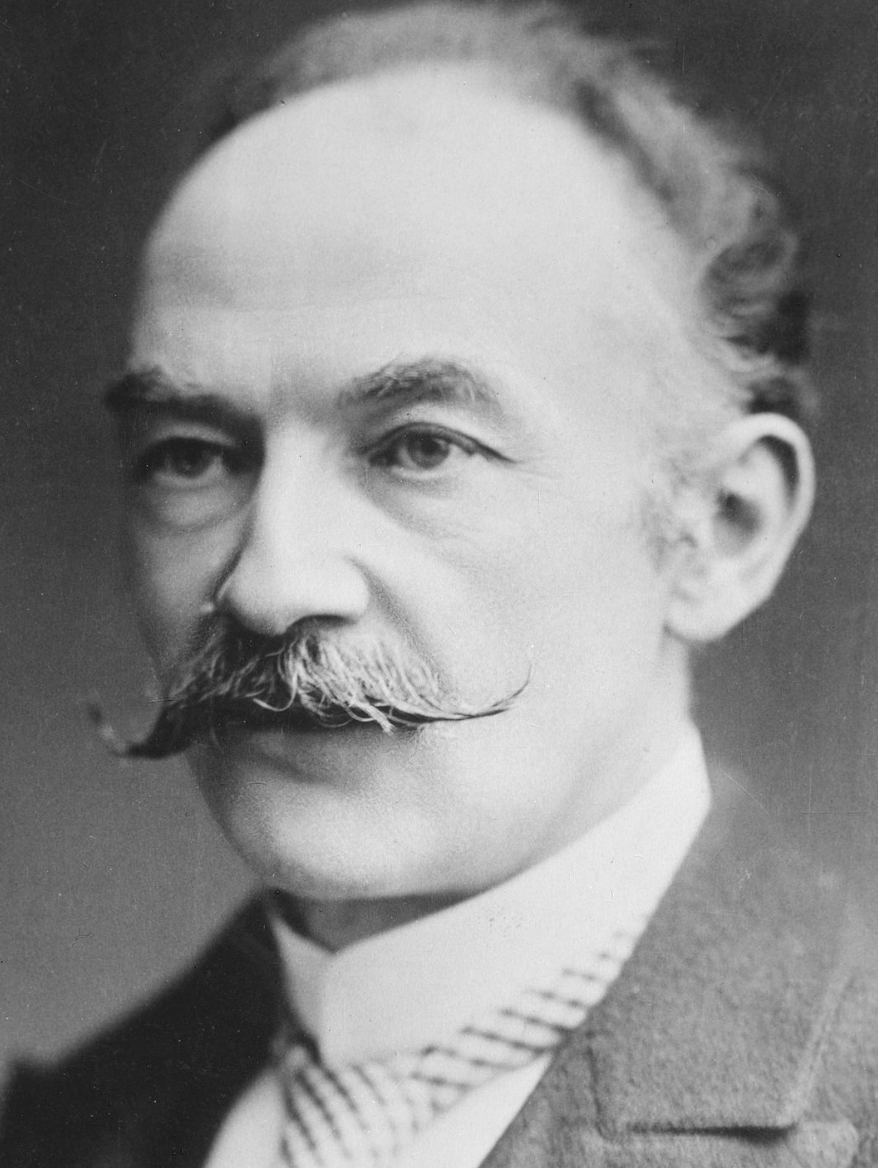

Thomas Hardy

On this date in 1840, poet and novelist Thomas Hardy was born in Upper Bockhampton, Dorset, England. His father Thomas was a stonemason and his mother Jemina (née Hand) was well-read and instilled a love of learning in her son. At age 16 he was apprenticed to an architect. Moving to London in 1862, he studied architecture at King’s College. While working as an architect’s assistant in his late teens and early 20s, Hardy considered pursuing ordination by the Anglican Church.

Biographer Timothy Hands in Thomas Hardy: Distracted Preacher? Hardy’s Religious Biography and its Influence on his Novels (1989) wrote that although loss of faith led to the abandonment of such plans, he in some ways remained steeped in Christianity and strongly objected to being called an atheist: “Thomas Hardy never entered the Church, but it is generally agreed that the Church most assuredly entered Thomas Hardy.” Hands dates Hardy’s “loss of faith” to 1865 when he was 25.

Hardy was small in stature, only a little over 5 feet tall. Health concerns led him back to Dorset after five years to concentrate on writing. A Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he came to regard himself primarily as a poet but first gained fame from his novels Far from the Madding Crowd (1874), The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886), Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) and Jude the Obscure (1895).

He was single until marrying Emma Gifford in 1874 when he was 34. Although they later became estranged (he was allegedly a neglectful husband), her death in 1912 affected him greatly. Two years later he married his secretary Florence Emily Dugdale, who was 39 years younger, but remained preoccupied with his first wife’s death and tried to overcome his remorse by writing poetry. He had no known children.

Scholars have strenuously debated his religious leanings. “Hardy slowly moved from the Christian teachings of his boyhood to become a thoughtful, questioning agnostic,” says the Humanists UK entry on Hardy.

Once, when asked in correspondence by clergyman A.B. Grosart about reconciling life’s horrors with “the absolute goodness and non-limitation of God,” he very formally replied: “Mr. Hardy regrets that he is unable to offer any hypothesis which would reconcile the existence of such evils as Dr. Grosart describes with the idea of omnipotent goodness. Perhaps Dr. Grosart might be helped to a provisional view of the universe by the recently published Life of Darwin and the works of Herbert Spencer and other agnostics.” (The Early Life of Thomas Hardy, 1840–1891, Florence Emily Hardy, 1928. She was credited as the author but Hardy himself wrote most or all of it in his later years.)

According to scholar Trish Ferguson, Hardy had long sought a rationale for believing in an afterlife or a timeless existence, turning first to spiritualists such as Henri Bergson and then to Albert Einstein, considering their philosophy on time and space in relation to immortality. Hardy was horrified by the death and destruction of World War I and wrote it was “better to let western ‘civilization’ perish, and let the black and yellow races have a chance.” (The Pessimism of Thomas Hardy, George William Sherman, 1976)

In Hardy’s poem “God’s Funeral” (1912), the narrator follows the procession to the grave and muses: “And though struck speechless, I did not forget / That what was mourned for, I, too, once had prized.”

According to Lawrence J. Clipper’s 1966 study guide to Hardy’s novel The Return of the Native (1878), “Hardy reflected Nietzsche’s agonized cry that ‘God is dead’ in his novels. His view of life was that since there is no God to give meaning to life, Man is alone in the Universe, no better and no worse than other creatures who live or have lived for a brief moment on this speck called Earth.”

Hardy died at age 87 during a bout with pleurisy. The death certificate listed “cardiac syncope” and “old age” as the causes. Despite his request to be buried alongside his first wife in Dorset, his ashes were interred in Westminster Abbey next to Charles Dickens in the abbey’s Poets’ Corner. But before cremation his heart was removed and lies in a churchyard next to Emma Hardy’s grave. (D. 1928)

“Peace upon earth!” was said. We sing it,

And pay a million priests to bring it.

After two thousand years of mass

We’ve got as far as poison-gas.— from Hardy's poem "Christmas: 1924"