April 26

David Hume

On this date in 1711, David Hume was born in Edinburgh, Scotland. The influential empiricist philosopher was raised by his widowed mother, a strict Calvinist. He entered the University of Edinburgh at age 11 and studied there for three years, after which he was self-educated.

His first philosophical book, A Treatise of Human Nature (1739-40), was guardedly skeptical (making references to “monkish virtues”). Critics used the book to deny Hume a teaching position at the University of Edinburgh and later at Glasgow University. Through this controversy, Hume humorously wrote a friend that he was “a sober, discreet, virtuous, frugal, regular, quiet, good-natured man, of a bad character.” (Cited in 2000 Years of Disbelief by James A. Haught.) Hume was finally granted a relatively congenial position as librarian at Edinburgh University in 1752.

In Essays, Moral, Political and Literary (1741), Hume dismissed priests as “the pretenders to power and dominion, and to a superior sanctity of character, distinct from virtue and good morals.” In An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748), he famously asserted that “a miracle can never be proved, so as to be the foundation of a system of religion.” Hume defined a miracle as “a violation of the laws of nature.”

His other books include The Natural History of Religion, which Hume, who was dying of cancer, arranged to be published posthumously. In The Natural History of Religion, Hume wrote: “Examine the religious principles which have, in fact, prevailed in the world, and you will scarcely be persuaded that they are anything but sick men’s dreams.” In the same work, Hume called the god of the Calvinists “a most cruel, unjust, partial and fantastical being.”

Hume also wrote The History of England (six volumes, 1754-61). The charitable and cheerful Hume was well-respected by fellow Britons, clergy excepted, and was on friendly terms with Adam Smith and Edward Gibbon. (D. 1776)

“The Christian religion not only was at first attended with miracles, but even at this day cannot be believed by any reasonable person without one.”

— Hume, "An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding" (1748)

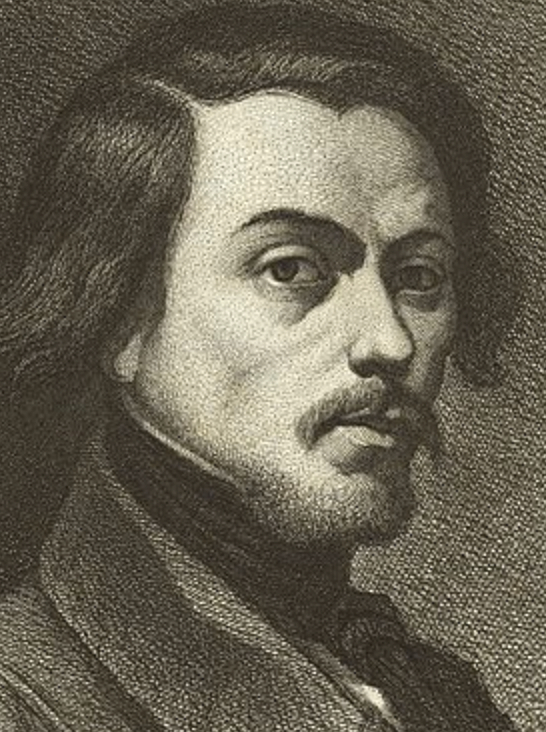

Eugène Delacroix

On this date in 1798, Eugène Delacroix was born in France. The painter was part of the Romantic movement and was known for such swashbuckling and colorful canvases as “Liberty Leading the People to the Barricades,” which marked the Revolution of 1830. One of his quieter canvases was a poignant, unfinished portrait of Chopin, which hangs in the Louvre.

Art historian Étienne Moreau-Nélaton wrote that Delacroix read and agreed with Diderot and Voltaire and had a secular funeral. (D. 1863)

“He wasn’t a practicing Christian. The subjects of his religious works were mainly well-known themes from the New Testament.”

— Biographical entry on Delacroix from Art and the Bible website

Samantha Cristoforetti

On this date in 1977, Italian astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti was born in Milan to Antonella and Sergio Cristoforetti. She completed her secondary education at the Liceo Scientifico in Trento in 1996 after having spent a year in Minnesota as a foreign exchange student at St. Paul Central High School.

She graduated in 2001 from the Technical University of Munich with a master’s degree in mechanical engineering with specializations in aerospace propulsion and lightweight structures. She wrote her master’s thesis on solid rocket propellants during a 10-month research stay at the Mendeleev University of Chemical Technologies in Moscow.

As part of her training for the Italian Air Force Academy, Cristoforetti completed a bachelor’s in aeronautical sciences at the University of Naples Federico II in 2005. She earned her fighter pilot wings in 2006 after a joint Euro-NATO training program at Sheppard Air Force Base near Wichita Falls, Texas. She was selected in 2009 as an astronaut by the European Space Agency (ESA) from among over 8,000 applicants, becoming Italy’s first female astronaut.

In 2014 she flew with an American and a Russian astronaut to the International Space Station (ISS) in low Earth orbit. The ISS is jointly owned and operated by the U.S., Russia, Japan, Canada and the ESA. As flight engineer, she stayed 199 days, setting the record for the longest single space flight by a woman until it was broken by American Peggy Whitson in 2017.

Mattel had honored Cristoforetti as a Barbie Shero, “a woman who has broken boundaries in order to inspire the next generation,” and her Barbie Role Model doll in a spacesuit floated in zero gravity next to her aboard the ISS. She had grown up enchanted by Gene Roddenberry’s “Star Trek,” and one day she posted a photo of her wearing a Starfleet pin and giving the Vulcan salute.

She is also a fan of Douglas Adams, author of “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.” A short video she made in space to memorialize Adams on her next mission got over 17 million views on TikTok. It shows her using a towel for various tasks, including drying her hair, and ends with “Happy Towel Day. And remember, don’t panic and always know where your towel is.” A towel is “just about the most massively useful thing an interstellar hitchhiker can carry” for practical and psychological reasons, Adams declared in the guide.

Cristoforetti’s second trip to the ISS launched in April 2022. She carried out the first spacewalk by a European woman and became the first European female commander of the ISS during her mission before coming home to Cologne, Germany, in October 2022.

At home were her husband, Lionel Ferra, a native of France employed by the ESA, and their children: Kelsi Amel (b. 2016) and Dorian Lev (b. 2021). Cristoforetti speaks Italian, English, German, French, Russian and Chinese. She published “Diary of an Apprentice Astronaut” in 2020, which was translated from Italian.

Asked once if it was harder becoming an astronaut or a mother, she replied: “I don’t know what was more difficult. In general, I think we should free ourselves from ‘ranking’ things the way journalists do. Real life experiences aren’t like that, you can’t quantify them.” (Sisters of Europe online, February 2019)

Her ESA bio says she “is an avid reader with a passion for science and technology, and an equal interest in humanities. … Occasionally she finds the time to hike, scuba dive or practice yoga.”

PHOTO: Cristoforetti in orbit about 250 miles from Earth; ESA/NASA photo.

“ ‘Of all the souls I have encountered … his was the most human.’ Thx @TheRealNimoy for bringing Spock to life for us.”

— @AstroSamantha tweet by Cristoforetti honoring Leonard Nimoy the day after he died, slightly shortening a line by James Kirk eulogizing Spock in "Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan" (Feb. 28, 2015)

Jonathan Rauch

On this date in 1960, Jonathan Charles Rauch — journalist, author and gay rights activist — was born in Phoenix, where he grew up. “I am a product of parents who married in 1951 at age twenty-one and twenty-two. My mother was a very bright young woman who gave up her graduate education to become a bored, unhappy housewife. My father was brought up in a man-in-charge world and found himself disoriented by his wife’s need for an independent life. My parents grew apart and their marriage ended in an angry divorce.” He was 12. (Journal of Law and Inequality, Summer 2010)

He called his Conservative Jewish upbringing “pretty thin actually. When I was a kid, you got a bar mitzvah and would never be seen [in synagogue] again. You didn’t really know what the prayers meant. You just said them. There was a sense of routinization about it, and that alienated me.” (Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Feb. 23, 2025)

His father had a successful law practice and raised Rauch and two siblings on his own while their mother moved to Berkeley, Calif., to start a new life. After graduating with a B.A. from Yale University in 1982, Rauch worked at the Winston-Salem Journal in North Carolina before moving to the nation’s capital in 1984. From 1984-89 he covered fiscal and economic policy for the National Journal.

In the ensuing years, he has written eight books and numerous articles in major publications on public policy, culture, lifestyle, religion and government. His award-winning column Social Studies appeared from 1998 to 2010 in the National Journal. As of this writing in 2025, he is a senior fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution and a contributing editor of The Atlantic.

Rauch has written extensively on LGBTQ+ civil rights issues. “Jesus himself had nothing to say about homosexuality, but he’s very clear on divorce. You can’t do it. And what I don’t understand is why gay people are the only people in America who have to follow biblical law. … I think what it boils down to is that gay people should deal with the same standards as straight people. And when straight people start upholding biblical law in civic culture, then maybe gay people should consider it, but not until then. (Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, April 24, 2008)

He and Michael Lai were married in the District of Columbia in 2010. “I owe my marriage to identity politics. In 1960, I was born into a world where openly homosexual Americans were legally banned from federal employment, informally banned from much private employment, terrorized on the streets, persecuted by police, pathologized by psychiatrists, reviled from the pulpit, and made to live a lie.” (The New York Review of Books, Nov. 9, 2017)

In a 2003 column, he wrote about someone asking him about his religious beliefs. ” ‘Atheist,’ I was about to say, but I stopped myself. ‘I used to call myself an atheist,’ I said, ‘and I still don’t believe in God, but the larger truth is that it has been years since I really cared one way or another. I’m — that was when it hit me — ‘an (pause) apatheist!’ ” He said religion “remains the most divisive and volatile of social forces.” (The Atlantic, May 1, 2003)

His views have softened since then, and in “Cross Purposes: Christianity’s Broken Bargain with Democracy” (2025), he wrote that he’s come to appreciate religion’s positive contributions and criticized the unwillingness or inability for some people to recognize that.

“Faith and secularism need each other to function. I think it’s necessary to address secular people like me and say, ‘Guys, we blew it. This Christianity is a load-bearing wall in our democracy, and to the extent that we help dismantle it, we’ve got to stop.’ … We need to make more space for people of faith to do their own thing, where that can be done with accommodations that don’t leave anybody else deprived of their rights.” (Ibid., JTA)

But, he added, “[W]e Jews can’t fix this. Christians made this mess, and Christians have to fix it at the end of the day.” In “Cross Purposes” he also takes Protestants to task for a “politicized, partisan, confrontational, and divisive” version of faith that has helped make America “ungovernable. … The problem is not just Christian nationalists who represent a militant belief in Christianizing the government, but everyday Christians who are sympathetic to the idea that their churches should focus on ‘winning in politics and winning in the culture wars.’ ”

PHOTO: Rauch in 2013; New America photo under CC 2.0.

“I have Christian friends who organize their lives around an intense and personal relationship with God, but who betray no sign of caring that I am an unrepentantly atheistic Jewish homosexual. They are exponents, at least, of the second, more important part of apatheism: the part that doesn’t mind what other people think about God.”

— Rauch, explaining why he also calls himself an apatheist (The Atlantic, May 1, 2003)