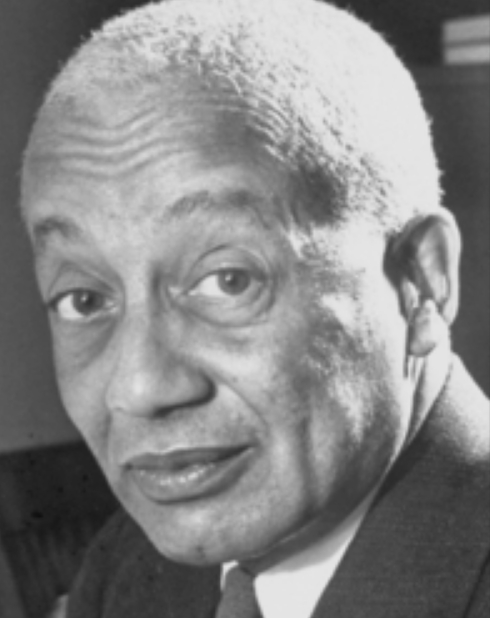

On this date in 1885, philosopher and author Alain LeRoy Locke, an instrumental figure in the Harlem Renaissance, was born in Philadelphia, the only child of Pliny Ishmael Locke — a law school graduate and the first black employee of the U.S Postal Service — and Mary Hawkins Locke, a teacher. His father died when Locke was 6, when he became even closer to his mother, who was an adherent of Felix Adler.

He was the first African-American Rhodes Scholar and went on to earn a Ph.D. in philosophy from Harvard University. It would be 56 years before another Black was awarded the Rhodes. The family’s religious background was Episcopalian, which Locke later disavowed when he became convinced the Baha’i faith with its “universalist” and humanist views and interracial meetings appealed more to him as a person of color. He would be reprimanded in 1920 while teaching at Howard University for his failure to attend chapel. He had received an assistant professorship there in 1912.

In The Philosophy of Alain Locke: Harlem Renaissance and Beyond (1989), editor Leonard Harris wrote, “Contrary to a Christian doctrine that there exists only one route to salvation, Locke holds that true universality requires a different view of spiritual brotherhood — one compatible with world peace.” In that same book Locke is quoted, “The idea that there is only one true way of salvation with all other ways leading to damnation is a tragic limitation [of] Christianity, which professes the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. How foolish in the eyes of foreigners are our competitive blind, sectarian missionaries!”

In a 2019 profile in The Humanist, Charles Murn wrote that Locke engaged in the culture wars of his time: “He attacked racism, color prejudice, discrimination against minorities, anti-Semitism, eugenics, and imperialism. While he was gay and mentored younger gay men, many of whom were artists, he did not seek to ease restrictions on homosexuality. He called for religious tolerance, yet confronted intolerance by religious leaders.”

Locke possessed a towering intellect (while physically small in stature at 4-foot-11), and after he was fired as chair of Howard’s philosophy department in 1925 for demanding pay equity for Black faculty, focused on publishing The New Negro: An Interpretation. A landmark in Black literature, the anthology contained Locke’s title essay and four more he wrote, along with poetry, art and prose by others, including Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes.

After being reinstated at Howard in 1928, he remained there until retiring in 1953. Leonard Harris notes that between 1912-53, most of the Black philosophy students at U.S. universities were either taught by Locke or by the philosophers he was instrumental in hiring at Howard. He also influenced students during visiting professorships in the mid-1940s at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the New School for Social Research in New York City. The philosophy department at UW-Madison was chaired at that time by Max Carl Otto, one of the earliest and most prominent scientific humanist philosophers.

He died of heart disease in New York City the year after retiring. Engraved on the tombstone under which lay his ashes is “Herald of the Harlem Renaissance” and “Exponent of Cultural Pluralism.” On the back are engraved a nine-pointed Baháʼí star, a bird that’s the national emblem of Zimbabwe, lambda gay rights and Phi Beta Sigma symbols and an African woman’s face set against the sun’s rays. Beneath the images are the Latin words “Teneo te, Africa” (I hold you, Africa). (D. 1954)