February 22

Luis Buñuel

On this date in 1900, film director Luis Buñuel Portolés was born in Calanda, Spain. After a strict Jesuit education gave him something to rebel against, he attended the University of Madrid, where one of his friends was Salvador Dalí. Buñuel moved to Paris, where his first film was the 21-minute “An Andalousian Dog” (Un Chien Andalou) in 1929, whose shocking opening made a deep impression. His first feature was “The Golden Age,” which attacked the church and the middle class, lifelong themes for Buñuel.

After the Spanish Civil War, he moved to the U.S. and worked as an editor at the Museum of Modern Art (1939-43) and as a film dubber for Warner Bros. before moving to Mexico. He became a Mexican citizen in 1948. His riveting study of Mexican street urchins, “The Young and the Damned” (1950) won him a Best Director award at the Cannes Film Festival. In 1961, Gen. Francisco Franco invited him back to Spain.

The first film he directed there was “Viridiana” (1961), in which Silvia Pinal plays a novice nun with a lecherous uncle and a charitable streak. It was banned for blasphemy in Spain but won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. Buñuel subsequently directed his best-known films, including “Diary of a Chambermaid” (1964) with Jeanne Moreau and Catherine Deneuve, “Belle de Jour” (1967) and the autobiographical “That Obscure Object of Desire” (1977).

The Catholicism he was raised with deeply imbued his worldview and work, even though he started having doubt about religion when he was 14. In his 1982 autobiography, he wrote: “As I drift toward my last sigh, I often imagine a final joke. I convoke around my deathbed my friends who are confirmed atheists, as I am. Then a priest, whom I have summoned, arrives; and to the horror of my friends I make my confession, ask for absolution for my sins, and receive extreme unction. After which I turn over on my side and expire. But will I have the strength to joke at that moment?”

He married actress and gymnast Jeanne Rucar in 1934. They had two sons, Juan Luis and Rafael, and remained married until his death in Mexico City from cirrhosis of the liver. (D.1983)

PHOTO: Buñuel at Cannes in 1954.

“Still an Atheist … Thank God!”

— Title of Chapter 15 in "My Last Sigh: The Autobiography of Luis Buñuel" (1982)

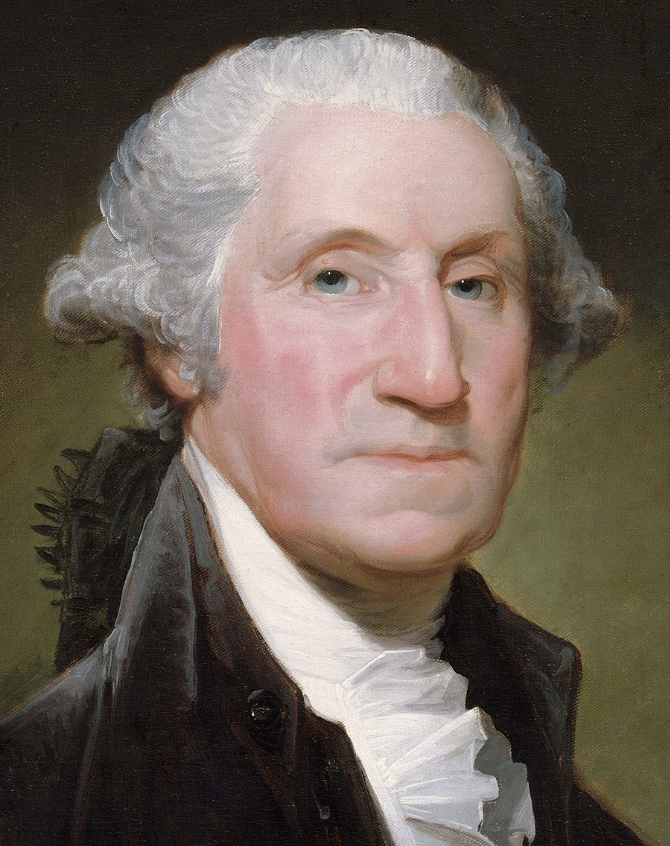

George Washington

On this date in 1732, George Washington was born in Popes Creek, Va., the eldest of six children. His father died when he was 11 and Washington inherited 10 slaves and a farm. He received a surveyor’s license in 1749 from the College of William & Mary and was appointed surveyor of Culpeper County. By 1752 he owned 2,315 acres of land.

Washington was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1758, was a delegate to the Continental Congress of 1774 and became commander of the Continental Army in 1775. He presided over the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, which adopted a godless constitution, and was elected the first U.S. president in 1789. He was reelected in 1793 and retired to Mount Vernon at the end of his second term. He married Martha Dandridge Custis in 1759 after her husband died when she was 25. Washington adopted her two children; two others had died.

Thought by many to be a deist, Washington has been claimed by many religions but kept his beliefs mostly to himself: “Religious controversies are always productive of more acrimony & irreconcilable hatreds than those which spring from any other source.” (Washington letter to Sir Edward Newenham, June 22, 1792.)

Jefferson recorded this on Feb. 1, 1800, in Memoir, Correspondence, And Miscellanies, From The Papers Of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 4: “Doctor Rush tells me that he had it from Asa Green, that when the clergy addressed General Washington on his departure from the government, it was observed in their consultation, that he had never, on any occasion, said a word to the public which showed a belief in the Christian religion, and they thought they should so pen their address, as to force him at length to declare publicly whether he was a Christian or not. They did so. However, he observed, the old fox was too cunning for them. He answered every article of their address particularly except that, which he passed over without notice. Rush observes, he never did say a word on the subject in any of his public papers, except in his valedictory letter to the Governors of the States when he resigned his commission in the army, wherein he speaks of ‘the benign influence of the Christian religion.’ I know that Gouverneur Morris, who pretended to be in his secrets and believed himself to be so, has often told me that General Washington believed no more of that system than he himself did.”

The foremost mythmaker about Washington was Parson Mason Weems, whose Life of Washington (1800) promoted the cherry tree story and other disinformation, such as the claim that Washington prayed in the woods at Valley Forge in the Revolutionary War winter of 1777-78.

Propagandists allege Washington wrote a Christian prayer, which is engraved on a bronze tablet at St. Paul’s Chapel in New York City. The source is not a prayer, but a business letter to governors, which makes two orthodox, deistic references (The Writings of George Washington, ed. Worthington Ford, 1889). Washington’s diaries reveal that he seldom attended church and often traveled on the sabbath. (D. 1799)

PHOTO: Washington in 1795 in an oil painting by Gilbert Stuart (cropped).

“Of all the animosities which have existed among mankind, those which are caused by difference of sentiment in religion appear to be the most inveterate and distressing, and ought most to be deprecated. I was in hopes that the enlightened and liberal policy which has marked the present age would at least have reconciled Christians of every denomination, so far that we should never again see their religious disputes carried to such a pitch as to endanger the peace of society.”

— Washington letter to Edward Newenham, June 22, 1792, "The Writings of George Washington, Vol. XII"

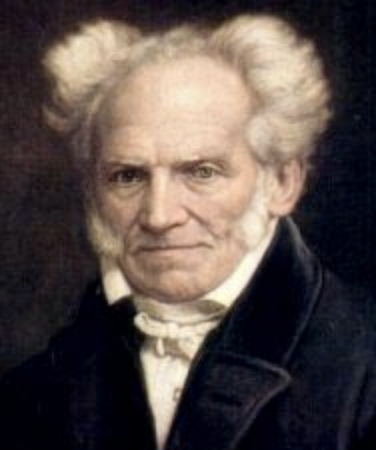

Arthur Schopenhauer

On this date in 1788, Arthur Schopenhauer was born in Danzig (present-day Gdańsk, Poland) to patrician parents of Dutch-German heritage who were political liberals and not very religious. When Danzig became part of Prussia in 1793, the family moved to Hamburg, Germany, a free city with a republican constitution. Schopenhauer studied philosophy at Gottingen, Berlin and Jena universities. His opus, The World as Will and Idea, was published in 1818 and revised in 1844.

Parerga and Paralipomena (Greek for Appendices and Omissions, 1851), was his final major work and contained his popular writings, aphorisms and essays. Schopenhauer was influenced by Kant and rejected the ideas of Hegel and proofs for the existence of God and immortality. He was also influenced by Buddhism. Although a loner and pessimist, he advocated the alleviation of suffering through an appreciation of aesthetics, altruism and asceticism. He died of respiratory failure at home at age 72 in 1860.

“For, as you know, religions are like glow-worms; they shine only when it’s dark. A certain amount of general ignorance is the condition of all religions, the element in which alone they can exist. And as soon as astronomy, natural science, geology, history, the knowledge of countries and peoples have spread their light broadcast, and philosophy is finally permitted to say a word, every faith founded on miracles and revelation must disappear; and philosophy takes its place.”

— Schopenhauer, "Parerga and Paralipomena" (1851)

Josephine K. Henry

On this date in 1846, Josephine Kirby Henry, née Williamson, was born into a wealthy family in Newport, Kentucky. She was 15 when her family moved to Versailles. She gave piano lessons and taught at the Versailles Academy for Ladies. In 1868 she married William Henry, who had served as a captain in the Confederate Army.

Henry was the first woman in the South to run for state office as a candidate of the Prohibition Party for clerk of the Court of Appeals in 1890, receiving nearly 5,000 votes in the notoriously anti-suffrage state. Kentucky was the last state in the union to grant women such basic rights as property ownership, guardianship of their children and the right to make a will. Henry was credited as the main force behind the adoption of the 1894 Woman’s Property Act, garnering 10,000 signatures.

Serving on the revising committee of Elizabeth Cady Stanton‘s The Woman’s Bible, Henry submitted two letters which were published in the appendix. For this heresy, she was declared an “undesirable member” of the Kentucky Equal Rights Association. Henry wrote a 30-page booklet, “Woman and the Bible” (1905), followed by a critique of the treatment of women in the institution of marriage: “Marriage and Divorce” (c. 1907).

She died in Versailles after suffering a stroke at age 84. (D. 1928)

“Is not the Church today a masculine hierarchy, with a female constituency, which holds woman in Bible lands in silence and in subjection? No institution in modern civilization is so tyrannical and so unjust to woman as is the Christian Church. It demands everything from her and gives her nothing in return.”

— from Henry's 1897 letter responding to Frances Willard's praise of "The Woman's Bible"

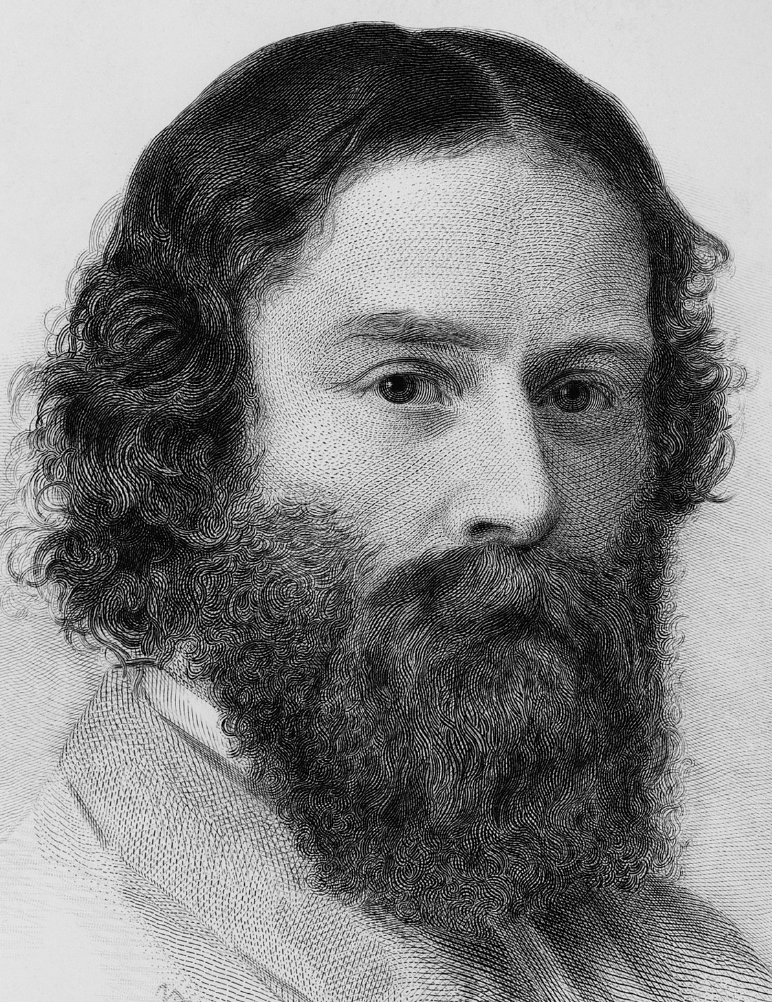

James Russell Lowell

On this date in 1819, poet James Russell Lowell was born in Cambridge, Mass., the son of a Unitarian minister in a family which went back eight generations in America. Lowell was one of the “Fireside Poets,” a group of New England writers that included Longfellow, Whittier and Holmes. Lowell earned his B.A. in 1838 and his L.L.B. in 1840 from Harvard. An ardent abolitionist, he left the law for literature, editing several journals.

He edited the Atlantic Monthly (1857-61) and the progressive North American Review (1864-72). A professor at Harvard for nearly 20 years, he also served as a minister to Spain and Great Britain. The poet wrote A Fable for Critics (1848), The Biglow Papers (serialized articles published in book form in 1848 and 1867) and The Vision of Sir Launfal (“And what is so rare as a day in June?”) in 1848.

Although Lowell’s poetry contains religious views that were conventionally 19th-century Unitarian, rationalist biographer Joseph McCabe suggested that, based on his later remarks, Lowell became agnostic. His later poetry included “The Cathedral “(1870), which dealt with the conflicting claims of religion and modern science.

He married the poet Maria White in 1844. They had four children, only one of whom survived childhood, before she died in 1853. He married Frances Dunlap in 1857. She died in 1885, six years before his death in 1891 at age 72.

“Toward no crimes have men shown themselves so cold-bloodedly cruel as in punishing differences of belief.”

— Lowell, "Literary Essays, Vol. II: Witchcraft" (1891)

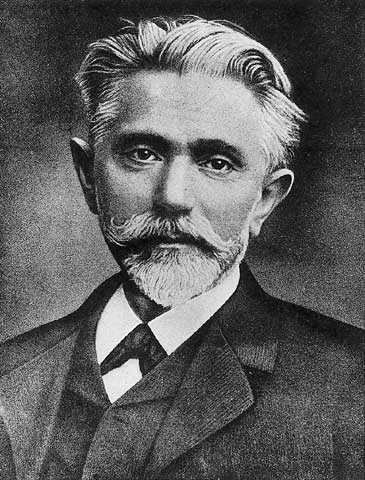

August Bebel

On this date in 1840, Ferdinand August Bebel, German politician and social reformer, was born in Cologne. As a young man he settled in Leipzig, the hub of German political activity, and became active with the radical Gewerblicher Bildungsverein (Industrial Educational Association). He studied Marx and Engels and other prominent figures in economic and social history. Bebel developed a reputation as a powerful speaker and was elected to the North German Constituent Reichstag in 1867, representing the Saxon People’s Party.

He believed less in revolution to effect social change and more in reforming existing political and social structures. Bebel believed women were enslaved through social institutions such as marriage, and his popular tract “Women and Socialism” (1897) advanced that idea. He co-founded the German Social Democratic Party in 1869, and by the time he died at age 73, his tract had been widely distributed and had been read at the Second International in Paris in 1889.

In his 1888 history of German socialism, British author William Harbutt Dawson wrote, “[Bebel] is without religion, and he is never tired of parading the fact, even having himself described in the Parliamentary Almanacs as ‘religionless.’ ” (D. 1913)

“We aim in the domain of politics at Republicanism, in the domain of economics at Socialism, and in the domain of what is today called religion at Atheism.”

— Bebel, Reichstag speech, March 31, 1881; quoted in "German Socialism and Ferdinand Lassalle: A Biographical History of German Socialistic Movements During This Century" by W.H. Dawson (1888)

Edna St. Vincent Millay (Quote)

“There is no God.

But it does not matter.

Man is enough.”“A job, something at which you must work for a few hours every day; an assurance that you will have at least one meal a day for at least the next week; an opportunity to visit all the countries of the world, to acquaint yourself with the customs and their culture; freedom in religion, or freedom from all religions, as you prefer; an assurance that no door is closed to you, that you may climb as high as you can build your ladder.”

— Poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, born Feb. 22, 1892 (D. 1950), "Conversation at Midnight," 1937. (She used the term "God" fairly freely in her writings, evincing some type of vague deism, except for this extract.) SECOND QUOTE: Millay, to poet and friend Arthur Ficke, when asked to name "five requisites for the happiness of the human race." ("The Poet and Her Book: A Biography of Edna St. Vincent Millay" by Jean Gould,1969)