On this date in 1927, singer Harry Belafonte (né Harold George Bellanfanti Jr.) was born in New York City in a Harlem hospital to Melvine “Millie” (Love) and Harold Bellanfanti Sr., respectively a maid/seamstress and a cook on a ship carrying bananas from Jamaica to the U.S.

His maternal grandparents were Scottish- and Afro-Jamaican, and his father was born on the island of Martinique to an Afro-Jamaican mother and a Dutch father of Jewish descent. That Belafonte’s parents were both undocumented likely led to the Anglicization of his surname. He attended Catholic services and parochial school. After Sunday Mass, his mother took him to the Apollo Theater to hear Cab Calloway or Count Basie or Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday or Ella Fitzgerald: “As suffocating and interminable as Mass seemed, I could endure it if I knew that a few short hours later I’d be in the real cathedral of spirituality.” (My Song: A Memoir, 2011)

“As my parents drifted apart, my mother grew more religious, which had direct implications for me,” Belafonte wrote. “My mother’s religion became everybody’s burden, especially my father’s.” His father’s fondness for alcohol didn’t help. (Ibid., My Song)

After a year in Jamaica living with his grandmother, he returned to New York, dropped out of high school and enlisted in the U.S. Navy, serving in 1944-45, loading ships bound for the Pacific from California. Just before he arrived in Port Chicago in Contra Costa County, a massive ammunition explosion killed 320 people, two-thirds of them Black sailors.

He started taking acting classes at the New School in the late 1940s alongside Marlon Brando, Tony Curtis, Walter Matthau, Bea Arthur and Sidney Poitier. Garnering roles in Broadway plays, he met Paul Robeson, one of his heroes. He had started singing in nightclubs to pay for acting classes, backed in his first appearance by the Charlie Parker combo. He signed a recording contract with RCA Victor in 1953.

Belafonte’s breakthrough album “Calypso” (1956) became the first million-selling LP by a single artist, spending 31 weeks at No. 1 on the Billboard charts. It included “Day-O” (The Banana Boat Song) and lines like “Lift six foot, seven foot, eight foot bunch/Daylight come and we want to go home.” Before long, he was making $50,000 a week with his Las Vegas show.

He had married Marguerite Byrd in 1948 and they had two daughters, Adrienne and Shari, but separated with Shari in utero. They divorced in 1957, the year that Belafonte and Joan Collins had an alleged affair during the filming of “Island in the Sun.” The marriage had been on shaky ground for some time and it stuck Belafonte as odd that Marguerite was resisting a divorce they both knew was inevitable. “One reason, for Marguerite, was her newfound Catholicism. … She knew how much I resented my Catholic education, and how fiercely I’d rejected the Church.” (Ibid., My Song)

Before the year was out, he married Julie Robinson, a former dancer with the Katherine Dunham Company who was of Jewish descent. They had a son, David, and in 1961 a daughter, Gina, the last of his children. They divorced in 2004 after 47 years of marriage. He married Pamela Frank, a photographer, in 2008. Neither wanted a religious wedding, so they married at Terrace in the Sky restaurant near Columbia University.

His artistry from the 1950s onward put him among fewer than two dozen EGOT recipients as of this writing in 2023 for winning Emmy, Grammy, Oscar and Tony awards for achievements in television, recording, film and Broadway theater. He recorded in genres from blues, folk, gospel, show tunes, jazz and American standards. He recorded two live albums at Carnegie Hall, performed at President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 inaugural and included harmonica player Bob Dylan on his 1962 LP “Midnight Special.”

He became friends with Martin Luther King Jr. and was deeply involved in the struggle for Black civil rights in a dangerous time. “For Martin the tenets of nonviolence aligned with his deep religious faith — and that I would struggle with, for unlike Martin, I questioned the honesty of the church and the existence of God. We’d talk a lot about that.” (Ibid., My Song) It was a time for strange bedfellows, as exemplified by Belafonte and actor Charlton Heston standing side by side at King’s massive march in 1963 on Washington, D.C.

Though he frequented churches during this period and later, it wasn’t about religion. “He’s not a believer, never was,” wrote author Jeff Sharlet, who interviewed Belafonte at age 84. “For him it’s political. He can’t forgive the church the slave catechism taught by traders of the flesh. … Every spiritual he sang on TV or in a concert hall was a message about this world, not the next. (Undertow: Scenes From a Slow Civil War, 2023)

The title track of his 1977 album “Turn the World Around” won plaudits after it was featured on “The Muppet Show” in 1979. He had discovered the song in the African nation of Guinea and the album was only released overseas. (“Water make the river/River wash the mountain/Fire make the sunlight/Turn the world around.”) He performed it at Jim Henson’s 1990 memorial, and in 2005 it was included in the official hymnal supplement of the Unitarian Universalist Association’s “Singing the Journey.”

He always credited his mother as a primary inspiration for his activism, with her words during his youth: “Don’t ever let injustice go by unchallenged.” (National Catholic Reporter, April 27, 2023) He died at age 96 from congestive heart failure at home in Manhattan, N.Y. (D. 2023)

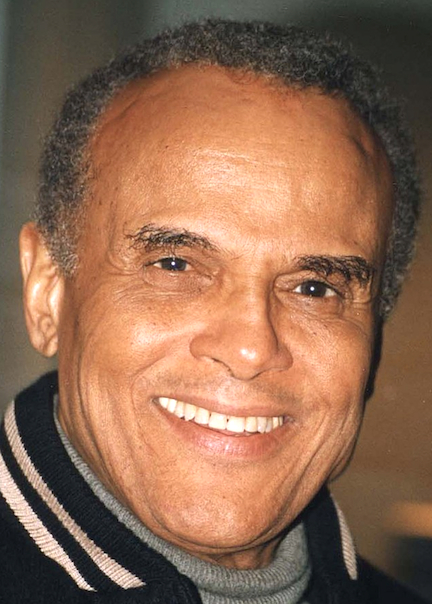

PHOTO: At Meyerhoff Symphony Hall in Baltimore in 1996; © copyright John Mathew Smith under CC 2.0.