psychologists

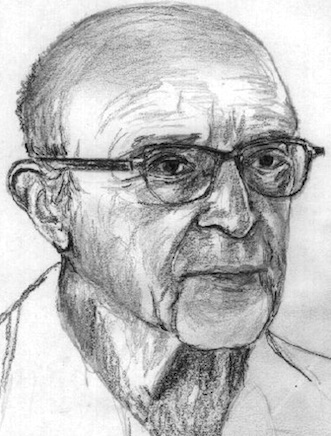

Carl Rogers

On this date in 1902, humanist psychologist Carl Ransom Rogers was born in Oak Park, Ill., one of five children of Walter and Julia Rogers. His conservative Protestant parents created a home filled with prayer and protection for their children from society’s influences. With few outside friends, Rogers led a quiet, sheltered life, reading and studying. Able to read before age 5, he skipped kindergarten and first grade and started school in the second grade.

Enrolling at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Rogers decided to study agriculture. He then changed his major to history and then to religion, intending to become a minister. While on a trip to China for an international Christian conference, Rogers started to doubt his religious convictions, although it took two years in seminary before he left his religious track. Rogers obtained his M.A. in education from Columbia University in 1928 and his Ph.D. in 1931. While working on his doctorate, he was involved in child studies at the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children in Rochester, N.Y., becoming the center’s director.

He began to engage in a new, humanistic approach to psychotherapy and in 1939 wrote his first book, “The Clinical Treatment of the Problem Child. He became a full professor at Ohio State University and, in 1942, wrote a second book, Counseling and Psychotherapy: Newer Concepts in Practice, wherein patients could gain the necessary insight to restructure their own lives in conjunction with an empathetic therapist. The premise of self-help and self-understanding was contrary to prior clinical methodologies, in which the psychologist told the patient what to do.

In 1945 he was asked to begin a new counseling center at the University of Chicago and, in 1951, published his groundbreaking work Client-Centered Therapy. Rogers became president of the American Academy of Psychotherapists in 1956 and a year later returned to UW-Madison to work in the psychology department. After becoming disillusioned with academia, he moved to La Jolla, Calif., in 1964, where he worked on the staff at the Western Behavioral Sciences Institute. In 1964 he was named “Humanist of the Year” by the American Humanist Association. He remained in La Jolla for the rest of his life.

Rogers wrote numerous journal articles and 16 books, the best known being On Becoming a Person (1962). He traveled worldwide to promote his theories in the areas of education, the social sciences and in national social conflict, specifically focusing his efforts on leading encounter groups between people of conflicting political factions.

He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1987 for his work with international intergroup conflict in South Africa and Northern Ireland. He died of a heart attack at age 85 in La Jolla. (D. 1987)

“Experience is, for me, the highest authority. The touchstone of validity is my own experience. … Neither the Bible nor the prophets — neither Freud nor research — neither the revelations of God nor man — can take precedence over my own direct experience.”

— Rogers, "On Becoming a Person" (1961)

Rebecca Newberger Goldstein

On this date in 1950, novelist and philosopher Rebecca Newberger was born in White Plains, N.Y. She was raised in an Orthodox Jewish household in White Plains and attended a Jewish high school for girls (or yeshiva) in Manhattan. Overcoming her upbringing, she “was born into consciousness” at Columbia University and received her bachelor’s degree in philosophy from Barnard College in 1972, graduating summa cum laude. She earned her Ph.D. in philosophy at Princeton in 1977.

She was a philosophy professor at Barnard, taught in the MFA writing program at Columbia and the philosophy department at Rutgers. For five years she was a visiting professor of philosophy at Trinity University in Hartford, Conn. Goldstein has been a visiting scholar at Brandeis University, a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University and a Guggenheim Fellow. She was the Miller Scholar at the Santa Fe Institute in 2011, a Franke Visiting Fellow at the Whitney Humanities Center, Yale University in 2012 and the Montgomery Fellow at Dartmouth College in 2013. She was also appointed a Visiting Professor of Philosophy at the New College of the Humanities in London, UK, in 2011 and a Visiting Professor at New York University in 2016.

In September of 2015 she was awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama. Previously she was named a MacArthur Fellow, known as the “Genius Award.” In 2005 she was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She has two daughters, Yael and Danielle, with her first husband, physicist Sheldon Goldstein. In 2007 she married Harvard psychologist and author Steven Pinker.

Her novels and nonfiction writing have received many awards. Her first novel, The Mind-Body Problem, which addresses philosophical themes, was published in 1983. Other novels include The Late-Summer Passion of a Woman of Mind; The Dark Sister, Mazel, and Properties of Light: A Novel of Love, Betrayal and Quantum Physics. Her book of short stories is called Strange Attractors. In 2005 she wrote Incompleteness: The Proof and Paradox of Kurt Godel, and in 2006, Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity, a biography of the 17th-century thinker.

In 2010 she returned to novel writing with Thirty-Six Arguments for the Existence of God: A Work of Fiction, a playful work with the timely theme of a protagonist who is author of a best-selling book on atheism. It concludes with a debunking of 36 arguments for the existence of God. In Plato at the Googleplex: Why Philosophy Won’t Just Go Away (2014), she imagines Plato’s take on the modern age with its technological wonders and argues that his philosophy is still relevant today.

In 2008 she was designated a Humanist Laureate by the International Academy of Humanism. In 2011 she was named Humanist of the Year by the American Humanist Association and a Freethought Heroine by the Freedom from Religion Foundation. Her FFRF acceptance speech, “Strong resistance to God’s existence,” is here.

LUKE FORD: “Tell me about you and God.”

REBECCA GOLDSTEIN: “I lived Orthodox for a long time. … I was torn like a character in a Russian novel. It lasted through college. I remember leaving a class on mysticism in tears because I had forsaken God. That was probably my last burst of religious passion. Then it went away and I was a happy little atheist.”— Goldstein, interview with Luke Ford at lukeford.net (April 11, 2006)

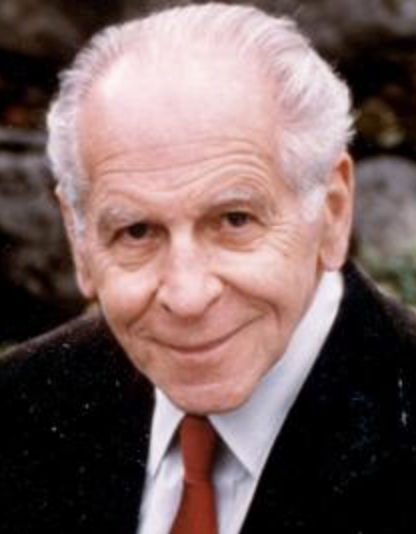

B.F. Skinner

On this date in 1904, behavioral psychologist Burrhus Frederic Skinner was born in Susquehanna, Pa., and grew up in what he called a “warm and stable” family. He was a child inventor who never lost his interest in invention. Skinner earned his B.A. in English at Hamilton College, New York, then went to Harvard for his master’s and doctorate in psychology.

He moved to Minneapolis when offered a teaching position at the University of Minnesota, where he married and had two daughters. He became chair of the psychology department at Indiana University in 1945, then was recruited by Harvard, where he stayed the rest of his life.

His wife, Yvonne, asked him to invent a “safe crib” when expecting their second child, something without bars. Skinner devised a “baby tender” for newborns, encased in soft Plexiglas, and wrote about the invention for a piece in the Ladies’ Home Journal, which dubbed the crib “Baby in a Box.” The contraption later led to some confusion with the “Skinner Box” he had used as an early researcher with rats.

Skinner was interested in “operant behavior” and wrote The Behavior of Organisms in 1938. His most famous book, Walden Two (1948), described an egalitarian, communal lifestyle. After sitting in one of his young daughter’s math classes, he became convinced that teaching methods should proceed by small steps, where students get feedback before advancing to the next level or question. He proposed a method comparable to tutoring children one-on-one.

The Technology of Teaching (1968) was adapted by some educators as the ideal, prescient model to employ when using computers to connect to their students via the World Wide Web. Other books include Verbal Behavior (1975), Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1971), About Behavioralism (1974), and three autobiographical volumes. An atheist, he was named Humanist of the Year by the American Humanist Association in 1972 and was inducted in 2011 into the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry’s Pantheon of Skeptics. He died at age 86 in Cambridge, Mass. (D. 1990)

PHOTO: by Silly Rabbit under CC 3.0.

"My Grandmother Skinner made sure that I understood the concept of hell by showing me the glowing bed of coals in the parlor stove. In a traveling magician’s show I saw a devil complete with horns and barbed tail, and I lay awake all that night in an agony of fear. Miss Graves [a teacher], though a devout Christian, was liberal. She explained, for example, that one might interpret the miracles in the Bible as figures of speech. … Within a year I had gone to Miss Graves to tell her that I no longer believed in God. ‘I know,’ she said, ‘I have been through that myself.’ But her strategy misfired: I never went THROUGH it."

— Skinner, "A History of Psychology in Autobiography, Vol. V" (eds. E.G. Boring and G. Lindzey, 1967)

Erich Fromm

On this date in 1900, psychoanalyst and humanist philosopher Erich Fromm was born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Grandfathers on both sides of the family were Orthodox rabbis. He earned his Ph.D. in sociology in 1922 from the University of Heidelberg and trained at the Psychological Institute in Berlin. By 1926 he had rejected Orthodox Judaism. Fromm took the story of Adam and Eve and turned it into an allegory in praise of the quest for knowledge, the questioning of authority and the use of reason.

He moved in 1930 to Geneva to escape Nazism, then emigrated to the U.S. in 1934. Fromm taught at Columbia University and became a citizen in 1940. His pinnacle work, Escape from Freedom, was published in 1941, followed by Man for Himself: An Inquiry into the Psychology of Ethics (1947).

Fromm moved to Mexico in 1950 to become a professor at the National Autonomous University, where he taught until 1965. The Art of Loving (1956) became an international best-seller. That was followed by The Sane Society (1955), You Shall Be as Gods (1966), The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness (1973), and To Have or to Be (1976). He started teaching in the U.S. again in the late 1950s at Michigan State University and later New York University.

He was a co-founder of several institutes, including the William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis and Psychology. As a critic of McCarthyism and the Vietnam War, he helped found the international peace group SANE.

In The Sane Society, Fromm distinguishes “intelligence” (“thought in the service of biological survival”) from “reason,” which “aims at understanding.” “In observing the quality of thinking in alienated man, it is striking to see how his intelligence has developed and how reason has deteriorated.” Fromm called ethics “inseparable from reason.”

Fromm “just didn’t want to participate in any division of the human race, whether religious or political,” wrote Keay Davidson in “Fromm, Erich Pinchas” ( American National Biography Online, Feb. 2000) and was a confirmed atheist. He moved to Switzerland in 1974, where he died just before his 80th birthday in 1980.

"If faith cannot be reconciled with rational thinking, it has to be eliminated as an anachronistic remnant of earlier stages of culture and replaced by science dealing with facts and theories which are intelligible and can be validated."

— Fromm, "Man for Himself" (1947)

Abraham Maslow

On this date in 1908, Abraham Harold Maslow was born, the first of seven children, to immigrant Russian Jewish parents in New York City. In 1928 he married his first cousin, Bertha Goodman. They had two daughters, Ann and Ellen. He received his B.A. in 1930 from City College of New York and his M.A. and Ph.D. in psychology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Maslow taught full-time at Brooklyn College and then at Brandeis, where he was named chair of psychology in 1951.

Maslow, a humanist-based psychologist, is known for proposing in 1943 the “hierarchy of needs” to be met so an individual can achieve “self-actualization.” In analyzing achievers, Maslow found they were reality-centered. Among his many books was Religion, Values and Peak-Experiences, which is not a freethought treatise, but which did not limit “peak experiences” to the religious or necessarily ascribe such phenomena to supernaturalism. In the book’s introduction, Maslow warned that mystics may become “not only selfish but also evil,” in single-mindedly pursuing personal salvation, often at the expense of others.

He’s also known for Maslow’s hammer, popularly phrased as “If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail,” from his book The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaissance (1966). He was named Humanist of the Year by the American Humanist Association in 1967. He died at 62 of a heart attack while jogging in Menlo Park, Calif. (D. 1970)

“We need not take refuge in supernatural gods to explain our saints and sages and heroes and statesmen, as if to explain our disbelief that mere unaided human beings could be that good or wise.”

— Description of Maslow's views by Richard J. Lowery, "A H. Maslow: An Intellectual Portrait" (1973)

Thomas Szasz

On this date in 1920, psychiatrist Thomas Szasz was born in Hungary. He earned a degree in physics from the University of Cincinnati in 1941, and his medical degree from the same university in 1944. His residency was in psychiatry. Szasz, went on to be a professor of psychiatry at the State University of New York-Syracuse and in 1990 the University made him a professor emeritus.

He was a critic of coercive psychiatry and a libertarian who supported suicide as a fundamental right. He favored abolition of the insanity defense and involuntary mental hospitalization, and refered to the “myth of mental illness.” His many books include The Manufacture of Madness, The Myth of Mental Illness, A Lexicon of Lunacy, and, with Milton Friedman, On Liberty and Drugs.

His freethought credentials included being named the 1973 Humanist of the Year by the American Humanist Association and being a Humanist Laureate with the Council for Secular Humanism. He has had a major influence on the field of psychiatry. (D. 2012)

“If you talk to God, you are praying. If God talks to you, you have schizophrenia.”

— Szasz, "The Second Sin" (1973)

Mary L. Trump

On this date in 1965, psychologist and author Mary Lea Trump was born in New York City to Linda Lee Clapp, a flight attendant, and Fred Trump Jr., a commercial airline pilot and future President Donald Trump’s older brother. She has a brother, Fred Trump III.

Her father died of a heart attack exacerbated by alcoholism at age 42 when she was 16. “We were sort of knee-jerk Protestants. We didn’t go to church much. I did Sunday School for a little bit. I actually used to wear a cross, which I think is hysterical now. As soon as my dad died, though, it was over for me.” (Sydney Morning Herald, Sept. 17, 2021)

She studied English literature at Tufts University in Massachusetts, earned a master’s in English literature at Columbia University and received a Ph.D. in clinical psychology from Adelphi University on Long Island, N.Y. Trump worked at the Manhattan Psychiatric Center while doing research for her doctorate and later taught graduate courses in developmental psychology, trauma and psychopathology. She received certification as a professional life coach and founded a New York-based company in 2012 called the Trump Coaching Group.

She contributed to the book “Diagnosis: Schizophrenia,” published by Columbia University Press in 2001. Her book “Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man” was an unauthorized 2020 biography of her uncle Donald. Legal efforts to stop publication failed and it sold nearly a million copies on the first day of sales.

Her 2021 book “The Reckoning: Our Nation’s Trauma and Finding a Way to Heal” detailed damage to the U.S. from what Trump called systemic racism and the nation’s failure to address the scourge of white supremacy. She hosts “The Mary Trump Show,” a podcast focusing on “politics, pop culture and everything in between.”

In “Too Much and Never Enough,” Trump said the family’s homophobia caused her to stay in the closet for many years out of fear of being disowned. She wrote that her grandmother, Mary Anne MacLeod Trump, called Elton John a “faggot” who shouldn’t be performing at Princess Diana’s memorial, so she hid her plans to marry a woman. Now divorced, Trump conceived a daughter, Avary, through in-vitro fertilization, raising her on Long Island.

She has expressed concern that “increasingly there is an empowering of white evangelical Christians who are increasingly intolerant and have an outsized voice in our politics. I don’t think you can be elected to higher office in this country if you don’t espouse religious views. That’s really troubling.” (Ibid.)

Asked how Donald Trump was able to successfully court evangelicals despite his lack of religion, she commented: “He certainly hasn’t read the Bible. This is a thrice-married person, with five children from three different marriages, who has 26 accusations of sexual assault against him. And yet you know what they said? That God ‘sometimes picks imperfect vessels.’ ” (Ibid.)

PHOTO: Trump at the Nexus Institute roundtable “Why is fascism popular again?” in December 2021. YouTube screenshot under CC 3.0.

“It just seemed absurd that there could be any kind of higher power. None of it made sense to me any more. So, since the age of 16, I have been an unwavering atheist. And I worry a lot about how religion is intertwined in politics in this country.”

— Trump, on the unexpected death of her father at age 42, Sydney Morning Herald (Sept. 17, 2021)

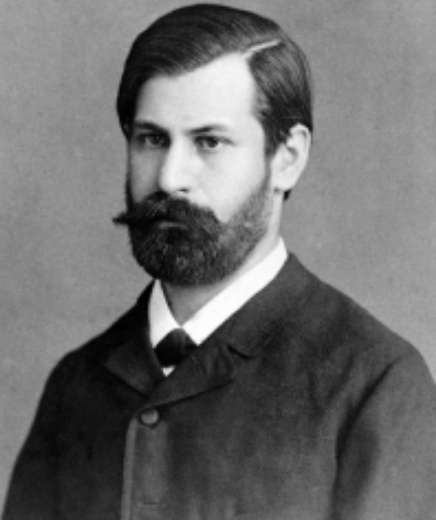

Sigmund Freud

On this date in 1856, Sigmund Freud was born in Moravia. He grew up in Vienna, where he lived until fleeing the Nazis in 1938. He earned a medical degree from the University of Vienna in 1881. He and Joseph Breuer co-wrote Studies in Hysteria (1895). Freud developed his theory on psychoanalysis, then wrote The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1904), Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious (1905), Three Essays on Sexual Theory (1905), Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920) and The Ego and the Id (1923).

The Future of an Illusion (1927) is his masterpiece critique of religion, postulating that God is a projection of childish father-figure preoccupations, that prayer and religious ritual are obsessive-compulsive and that religion is a “universal neurosis.”

Freud followed that with Moses and Monotheism (1938), in which he wrote: “[Religion’s] doctrines carry with them the stamp of the times in which they originated, the ignorant childhood days of the human race. Its consolations deserve no trust.” Civilization and its Discontents (1929) also addressed Freud’s views on religion. In The Future of an Illusion he wrote that “in the long run, nothing can withstand reason and experience, and the contradiction which religion offers to both is all too palpable.”

In 1933 he collaborated with Albert Einstein on Why War?, a compilation of their memorable correspondence. Dying of mouth cancer after more than 30 operations, Freud ended his suffering with physician-prescribed morphine. (D. 1939)

"Religion is comparable to a childhood neurosis."— Freud, "The Future of an Illusion" (1927)

Janet Jeppson Asimov

On this date in 1926, humanist Janet Opal Asimov (née Jeppson), was born into a Mormon family in Ashland, Pa. While known for her fiction writing, science columns and accomplishments in psychiatry and psychoanalysis, her marriage to Isaac Asimov in 1973 added further prominence. She enrolled at Wellesley College, where “I came to think of death as a disorganization of the patterns called living with nothing supernatural left over,” according to The Humanist (March 4, 2019).

She earned a B.A. degree from Stanford University, an M.D. degree from New York University Medical School and in 1960 graduated from the William Alanson White Institute of Psychoanalysis, where she continued to work until 1986. After her marriage she practiced psychiatry as Janet O. Jeppson and published medical papers under that name.

Her first story was published in The Saint Mystery Magazine in 1966. She would eventually publish 27 works, including six novels, and switched to her married name to co-write science fiction with Isaac. They released the young-adult novel Norby, the Mixed-Up Robot in 1983 and followed it with nine others in the Norby Chronicles series. He was later quoted that despite the joint byline, she did 90 percent of the work. After his death in 1992, she took over writing his syndicated Los Angeles Times science column. She died in New York at age 92. (D. 2019)

PHOTO: By Chris Johnson © photo, cropped; used with permission.

“I think one reason believers have hidden depression is that in the effort to ensure that they and their loved ones live forever, they don't really live in the present. They worry about past sins and future punishments or rewards. They even louse up the environment because only heaven matters."

— Janet Asimov, quoted in "A Better Life: 100 Atheists Speak Out on Joy & Meaning in a World Without God" by Chris Johnson (2013)

Linda LaScola

On this date in 1945, Linda LaScola — qualitative researcher, clinical social worker and Clergy Project co-founder — was born to Elvira (née Favorite) and Philip LaScola in New Castle, Pa. Her mother was a housewife and clerk typist. Her father was a wholesale produce merchant. The youngest of three children, she had a stable and very happy childhood.

“Although we went to church every Sunday, we weren’t very religious,” LaScola said. “My mother refused to send us to Catholic schools. She didn’t go to church much herself, claiming ‘claustrophobia,’ and my father guiltlessly skipped [mandatory Mass on] holy days.” (In-sight Journal, Dec. 5, 2016)

She attended church less at Penn State University, where she earned a B.S. in secondary education in 1967. “Though I still believed in God, there was too much silliness in Catholicism for me to take the religion seriously. After about 20 years of marriage and without children, my husband, an agnostic, and I started attending an Episcopal Church, to fill his need for community.” (Ibid.)

Her employment included recreation and case work for the American Red Cross and five years as a U.S. Capitol tour guide during which she went back to school and earned a master’s degree in social work in 1979 from the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. She had married Arthur Siebens that same year after they’d met at a neighborhood public library.

Alcohol abuse and issues affecting work performance took up much of her time as a social worker. A natural outgrowth of that was her subequent career in qualitative research, which is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences to gather in-depth insights into an issue or to generate new ideas for research.

In a speech to FFRF’s national convention in 2016, LaScola detailed her project with nonbelieving clergy:

When I made my personal academic study of religion in 2005-2006, I learned that clergy learn about the mythological basis for the bible in seminary. As a qualitative researcher and former clinical social worker, I couldn’t figure out how they could then go out and teach and preach something they knew wasn’t true. How could they deal with the cognitive dissonance? I learned that philosopher Daniel Dennett had the same question. So, to make a long story very short, we teamed up with Tufts University to conduct a small pilot study, and then a larger study of 35, including current and former pastors, seminary students and professors.

Their 2010 paper in Evolutionary Psychology on the pilot study was titled “Preachers Who Are Not Believers” and was expanded in 2013 for their book “Caught in the Pulpit: Leaving Belief Behind.”

In 2011, LaScola became a co-founder of The Clergy Project, along with Dennett, FFRF’s Dan Barker, Richard Dawkins, a pastor called “Chris” and another named “Adam,” the latter who came out publicly in 2016 as Carter Warden. It launched with 52 charter members in a collaborative effort to provide online space where deconverted clergy could gather to support and encourage one another.

“The Unbelieving,” a 90-minute, off-Broadway play that was years in the making and was produced by LaScola and Dennett with staging by The Civilians theater company was scheduled for a 2022 run from Oct. 20 through Nov. 20 at 59E59 Theaters. The playwright is Marin Gazzaniga. Based on interviews conducted for “Caught in the Pulpit,” the play is described as a “classic tale of religious conversion, [in which] finding God holds the promise of a life filled with purpose and meaning. But what happens when this transformation occurs in reverse, and a faith you have built your life around begins to fall away?”

LaScola also blogged extensively at Rational Doubt on Patheos. As of this writing in 2022, she and her husband live in Washington, D.C., and The Clergy Project has over 1,000 members.

“After about a year of reading and taking adult education classes at church, I realized there was nothing to believe and we left. My husband, who, like me, now identifies as an atheist, has since joined an Ethical Society and a Unitarian Church. I stay home and read the paper.”

— Interview, In-sight Journal (Dec. 5, 2016)

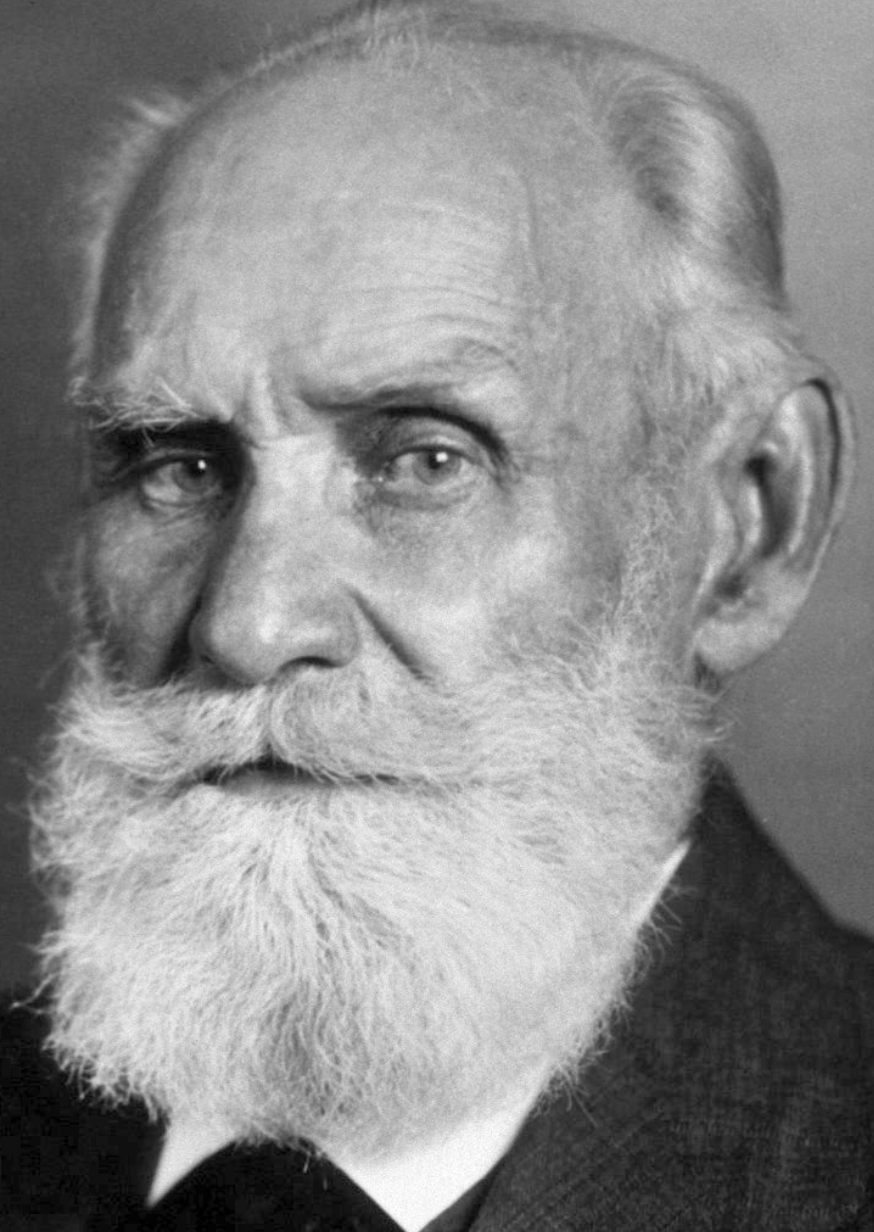

Ivan Pavlov

On this date in 1849, Ivan Petrovich Pavlov was born in Ryazan, Russia. He enrolled in Ryazan Ecclesiastical Seminary in the 1860s. In 1870 he dropped out in order to study natural sciences at the University of St. Petersburg. He graduated in 1875 and went on to attend the Academy of Medical Surgery. Pavlov became a professor of pharmacology at the Military Medical Academy in 1890 and director of the department of physiology at the Institute of Experimental Medicine in 1891, where he studied the physiology of the digestive system, often using dogs as research subjects.

He wrote books about his research, including Work of the Digestive Glands (1897). In 1904 he earned the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for his work with digestive organs. Pavlov married his wife, Serafima, in 1881.

Despite Pavlov’s influential research on the digestive system, he is most famous for his discovery of classical conditioning: teaching an animal to associate a reflex with an unrelated stimulus. Pavlov made the discovery while researching the salivary glands of dogs, after he noticed that dogs salivated when they anticipated food in addition to when they began eating. This led him to condition the dogs to begin salivating when they saw or heard a variety of stimuli, most famously, bells. He accomplished this by ringing a bell every time he fed the dogs, making them associate bells with food.

Pavlov described himself as an atheist who lost his faith when he was a seminary student. “In regard to my religiosity, my belief in God, my church attendance, there is no truth in it; it is sheer fantasy,” Pavlov told his student Evgenii Mikhailovich Kreps in the 1920s, according to the article “Pavlov’s Religious Orientation” by George Windholz (1986). Windholz also quoted Pavlov as saying, “There are weak people over whom religion has power. The strong ones — yes, the strong ones — can become thorough rationalists, relying only upon knowledge, but the weak ones are unable to do this.” D. 1936.

"Humans saved themselves by creating religion, which enabled them to maintain themselves somehow, to survive in the midst of an uncompromising, all-powerful nature. It is a very basic instinct that is thoroughly rooted in human nature."

— Pavlov, quoted in "Pavlov's Religious Orientation," Vol. 25 of the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 1986

Albert Ellis

On this date in 1913, Albert Ellis was born in Pittsburgh, Pa. He graduated from the City University of New York with a degree in business and later decided to earn a Ph.D. in clinical psychology from Columbia University. He worked as a psychotherapist, marriage and family counselor and sex therapist. He became chief psychologist of New Jersey in 1950.

Ellis initially practiced psychoanalysis but in 1953 he declared it unscientific and became what he called a “rational therapist.” In 1955 he formulated Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT), a type of short-term cognitive behavioral therapy that counseled patients to take action to improve their lives in the present instead of focusing on past experiences. He founded the nonprofit Albert Ellis Institute in 1964, which worked to promote REBT and make it accessible. REBT was considered a revolutionary change in psychotherapy. A 1982 study found that Ellis was considered more influential than such famous psychologists as Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung.

Ellis became a “firm atheist and anti-mystic” at age 12, according to his 2007 book Are Capitalism, Objectivism, and Libertarianism Religions? Yes!. In the book, he also called himself a “probabilistic atheist,” meaning that he believed the probability of a god existing was very low. “We can have no certainty that God does or does not exist [but] we have an exceptionally high degree of probability that he or she doesn’t,” Ellis explained in his 2004 book, Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy: It Works For Me – It Can Work For You.

Ellis wrote “Case Against Religion: A Psychotherapist’s View and the Case Against Religiosity,” which was first published in The Independent in 1980 and later published as a pamphlet. He wrote that religion’s “absolutistic, perfectionistic thinking is the prime creator of the two most corroding of human emotions: anxiety and hostility.” D. 2007.

"For a man to be a true believer and to be strong and independent is impossible; religion and self-sufficiency are contradictory terms."

— Ellis, “Case Against Religion: A Psychotherapist’s View and the Case Against Religiosity,” 1980.

Margaret K. Knight

On this date in 1903, psychologist Margaret Kennedy Knight, née Horsey, was born in Hertfordshire, England, earning her bachelor’s degree at Girton, Cambridge, in 1926 and her master’s in 1948. “I had been uneasy about religion throughout my adolescence, but I had not had the moral courage to throw off my beliefs until my third year in Cambridge,” she wrote in the 1955 preface to Morals Without Religion. “A fresh, cleansing wind swept through the stuffy room that contained the relics of my religious beliefs. I let them go with a profound sense of relief, and ever since I have lived happily without them.”

She married Arthur Knight, a professor of psychology, in 1936, then moved with him to Aberdeen, Scotland, and lectured at the University of Aberdeen from 1936-70. She and her husband co-wrote several textbooks. She became a celebrity across Great Britain when she achieved the coup of promoting freethought on BBC Radio. Seeking to uncouple moral education from religion, Knight had submitted a draft script in 1953 after long negotiations. The BBC finally agreed that as a psychologist, she could broaden her approach to include “positive advice to non-Christian parents on the moral training of children.”

The fireworks started after her first talk in January 1955 was written up in newspapers, including the Sunday Graphic story headlined “The Unholy Mrs. Knight” describing her as “a menace.” The BBC lectures appeared in her 1955 book Morals Without Religion. In 1961 she edited Humanist Anthology From Confucius to Bertrand Russell (revised in 1995 by James Herrick) and updated her views on religion in the 1975 pamphlet “Christianity: The Debit Account.” (D. 1983)

"Ethical teaching is weakened if it is tied up with dogmas that will not bear examination."

— Knight, "Morals Without Religion" (1955)