November 6

Pat Tillman

On this date in 1976, NFL player Patrick Daniel Tillman was born to Mary (Spalding) and Patrick Tillman in San Jose, Calif., the first of their three sons. He grew up in a household without a television where he and his brother largely read or played outdoors. As a teen he wrote in his journal that he considered himself an atheist. As a high school senior he led his team to the Central Coast Section Division I Football Championship. He helped lead the Sun Devils at Arizona State University to the 1997 Rose Bowl after an undefeated regular season and graduated summa cum laude from ASU’s School of Business.

He signed with the Arizona Cardinals in 1998, played defensive safety and broke the franchise record for tackles in 2000 with 224. He also competed in marathons and the Ironman triathlon and volunteered in youth groups and schools while pursuing a master’s degree in history. He married his high school sweetheart, Marie Ugenti, in 2002. He soon made his stunning announcement that he was placing his NFL career on hold to become a U.S. Army Ranger with his brother Kevin. They served tours in Iraq during Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003 and in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom in 2004.

They were recipients of the Arthur Ashe Courage Award at the 11th Annual ESPY Awards in 2003. Tillman died from what was officially termed as “friendly fire” as he tried to provide cover for fellow Rangers escaping an ambush in a canyon in Afghanistan on April 22, 2004. It took the Army five weeks to disclose what it said was the truth to his family — that he was a victim of fratricide. When his anti-war views — he had grown to see the war as illegal — were documented by his family, they were attacked by right-wingers. Several investigations, including congressional probes, ensued that revealed suspicion that Tillman was actually murdered and that friendly-fire evidence was contrived.

The program for his memorial service featured a quote by Ralph Waldo Emerson, which had been found underlined in Tillman’s belongings: “But the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.” In an article in October 2006 appearing in Truthdig, Kevin Tillman wrote that the best way to honor his brother was by choices made on “the day after Pat’s birthday” (Nov. 7, Election Day). Kevin Tillman wrote: “Somehow suspension of habeas corpus is supposed to keep this country safe. Somehow torture is tolerated. Somehow lying is tolerated. Somehow reason is being discarded for faith, dogma and nonsense.” (D. 2004)

"Hold your spiritual bromides. … Pat isn’t with God. He’s f-ing dead. He wasn’t religious. So thank you for your thoughts, but he’s f-ing dead."

— Richard Tillman at his brother Pat's memorial service, San Francisco Chronicle (May 4, 2004)

Vashti Cromwell McCollum

On this date in 1912, champion of the First Amendment Vashti McCollum, née Cromwell, was born in Lyons, New York, the daughter of Arthur G. and Ruth Cromwell. Arthur was a noted atheist activist in Rochester. Vashti was named by her mother for the biblical character who was “the first exponent of woman’s rights.” She studied at Cornell and the University of Illinois but on the verge of graduation married John Paschal (“Pappy”) McCollum in 1934. He was a University of Illinois horticulture department professor. They had three children before she completed her degree in political science and law in 1944.

The couple’s idyllic life as a faculty family in Champaign changed radically when their oldest boy, Jim, entered the fourth grade and was pressured to participate in religious instruction. When she withdrew Jim from the class, he was put in what amounted to detention. After filing suit to stop the unconstitutional instruction, she lost her job at the university and was branded “that awful McCollum woman.” The family became pariahs to much of the community.

Despite losing at both the trial and appellate levels, McCollum did not give up. On March 8, 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court, in a decision delivered by Justice Hugo Black, vindicated her in an 8-1 decision that is still precedent. She wrote her classic account One Woman’s Fight in 1951 and went on to serve two terms as president of the American Humanist Association and received its distinguished service award.

McCollum earned her master’s degree in mass communication as a returning student and by the late 1950s became a world traveler, often going “surface,” visiting nearly 150 countries and all seven continents, including Antarctica. She was an FFRF honorary officer, was featured in the foundation’s 1988 film “Champions of the First Amendment” and was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

The New York Times, Los Angeles Times and major British newspapers all carried stories of her death in 2006 at age 93.

"Between being praised and persecuted, condoned and condemned, I might understandably have become bewildered, particularly at the brand of ethics sometimes displayed by the staunch defenders of Christianity. But of one thing I am sure: I am sure that I fought not only for what I earnestly believed to be right, but for the truest kind of religious freedom intended by the First Amendment, the complete separation of church and state."

— Vashti Cromwell McCollum, "One Woman's Fight" (1951)

Francis Ellingwood Abbot

On this date in 1836, philosopher and theologian Francis Ellingwood Abbot was born into a family of Boston transcendentalists. Educated at Harvard and Meadville Theological School. He graduated from Harvard ranked number one in the class of 1859 and then married Katharine Fearing Loring. He became a Unitarian minister but by 1868 was forced to leave the pulpit in Dover, N.H., because his views were seen as too radical. New Hampshire’s highest court ruled in 1868 that he was “insufficiently Christian” to serve a splinter congregation in the building owned by the First Unitarian Society of Dover.

By now an avowed Darwinian, Abbot moved to Toledo, Ohio, to serve a Unitarian congregation but by 1872 it had dwindled in size to the point where members stopped paying his salary. Giving up on the pulpit, he founded the Free Religious Association and its journal The Index, a weekly paper “devoted to free religion” and “scientific theism.” He edited the paper until 1880, then founded another freethought journal, The Open Court. He taught at a boy’s school from 1881-92 in Cambridge, Mass.

Abbot wrote extensively. His books include Scientific Theism (1885), The Way Out of Agnosticism, or the Philosophy of Free Religion (1890) and The Syllogistic Philosophy, or Prolegomena to Science (two volumes, posthumously in 1906). In 1903, distraught on the 10th anniversary of his wife Katie’s death, Abbot died at age 66 on her grave in Beverly, Mass., after taking an overdose of sleeping pills. Theirs was a great love, author Brian Sullivan wrote in If Ever Two Were One: A Private Diary of Love Eternal (2005), a collection of Abbot’s correspondence and diary entries.

In 1894, a year after Katie’s death, he wrote, “[H]er soul was the violet of my home, fragrant with heaven’s own breezes, and lovely with a modest charm that kept me and keeps me her lover as in the days of yore.” (D. 1903)

“That great and growing evils render it a paramount patriotic duty on the part of American citizens, who comprehend the priceless value of pure Secular government, to take active measures for the immediate and absolute secularization of the state, and we earnestly urge them to organize without delay for this purpose.”

— Francis Ellingwood Abbot, from "Nine Demands of Liberalism," The Index (April 6, 1872)

Thandiwe Newton

On this date in 1972, a film star was born in London. Thandiwe Newton, a culturally diverse British woman with a flair for the arts, spent her early days living in Africa and England. Her parents had met in a hospital in Zambia. Her mother, a Zimbabwean health care worker, and her father, a British lab technician, moved back to Zambia after Newton was born and remained there until they were forced to seek political refuge.

In the UK, Newton pursued a career in dance while attending the University of Cambridge. She earned a degree in social anthropology in 1995. A back injury prevented her from attaining her dream of becoming a famous dancer. Her film debut was in 1991 in the Australian movie “Flirting.” She then had roles in “Interview with a Vampire” (1994), “Beloved” (1998), “Mission Impossible: II” (2000), “Crash” (2004), “The Pursuit of Happiness” (2006), “Norbit” (2007), “Vanishing on 7th Street” and “For Colored Girls” (2010), “Good Deeds” (2012), “Half of a Yellow Sun” (2013), “Solo: A Star Wars Story” and “The Death and Life of John F. Donovan” (2018).

In 2006 she received BAFTA, London Critic Circle Film and Empire awards for her performance in “Crash.” Her portrayal of Condoleezza Rice in “W” (2008) also earned her accolades. In 2016, she started portraying Maeve Millay in the HBO science fiction drama series “Westworld,” for which she won the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Drama Series.

Newton married English writer, director and producer Ol Parker in 1998. They have three children: daughters Ripley (b. 2000) and Nico (b. 2004) and son Booker Jombe (b. 2014). Asked what spiritual path she follows during an interview about her film “For Colored Girls,” she answered “Buddhism.”

"I grew up on the coast of England in the ’70s. My dad is white from Cornwall and mum is black from Zimbabwe. Even the idea of us as a family was challenging to most people, but nature had its wicked way and brown babies were born. But from about the age of 5 I was aware that I didn't fit, I was the black atheist kid in the all-white Catholic school run by nuns, I was an anomaly."

— Newton, "Embracing otherness, embracing myself," TEDGlobal 2011, Edinburgh, Scotland (July 14, 2011)

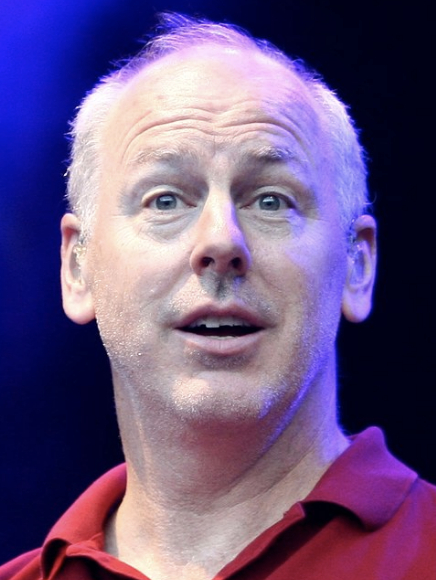

Greg Graffin

On this date in 1964, Gregory Walter Graffin was born in Racine, Wis. Graffin says he was raised in “an absolute vacuum of religion.” His father was a University of Wisconsin English professor. His parents divorced and he moved with his mother to Los Angeles when he was 11.

Graffin co-founded the punk rock band Bad Religion in 1980. The band released “Age of Unreason” in 2019, its 17th studio album. It was among the headliners at the 2012 Reason Rally in Washington, D.C., where Graffin sang the national anthem. He earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from UCLA and a Ph.D. in zoology in 2003 from Cornell University. His thesis examined religion’s effect on humanity and included asking evolutionary biologists if they believed in God; almost 90% of those surveyed did not.

His books include Is Belief in God Good, Bad or Irrelevant? A Professor and Punk Rocker Discuss Science, Religion, Naturalism & Christianity (with Preston Jones), Evolution and Religion, Anarchy Evolution: Faith, Science, and Bad Religion in a World Without God (with Steve Olson) and Population Wars: A New Perspective on Competition and Coexistence. As of this writing he teaches a course on evolution for non-majors at Cornell between band tours.

Graffin calls himself a naturalist and says while he doesn’t believe in God, he’d rather not be called an atheist because “it’s not really saying much about how you came to that conclusion.” He received the Outstanding Lifetime Achievement Award in Cultural Humanism from Harvard University’s Humanist Chaplaincy in 2008.

He married Greta Maurer in 1988. After divorcing in 1996, he married Allison Kleinheinz in 2008. He has a daughter, Ella, and a son, Graham, with Greta.

PHOTO: Graffin in Germany with Bad Religion at the Taubertal Festival 2013; photo by Antje Naumann under CC 3.0.

"If you can believe in God, then you can believe in anything. It's a gang mentality."

— Graffin, wired.com interview (November 2006)

Robert Ellis

On this date in 1988, singer-songwriter and guitarist Robert Ellis was born in Lake Jackson, Texas. He was raised on country and bluegrass music and dropped out of high school his junior year to take music classes at a community college. He began performing with his band Robert Ellis and the Boys around Houston in 2010. For a time they appeared weekly at Fitzgerald’s in Houston on what came to be known as “Whiskey Wednesdays.” They played classic country covers and eventually original material written by Ellis.

Ellis released his first LP “Photographs” in 2011. In 2012 he performed at the Bonnaroo music festival. He has toured with groups like Old Crow Medicine Show, The Old 97’s and Deer Tick. In 2014 he moved to Nashville to record “Lights From The Chemical Plant,” which features the song “Sing Along.” Ellis called the song “a traditional bluegrass atheist anthem.”

Although Ellis was raised in a religious family in a conservative community, he is an “affirmed atheist.” In 2014 he said, “I was raised very religious, indoctrinated even. I have a little bit of resentment about the way people went about it and still go about it, but most musical people have a slightly different outlook.” (The UK Independent, March 14, 2014) Ellis was nominated for the Americana Music Association’s award for Album of the Year and Artist of the Year in 2014.

PHOTO: Ellis in 2012; photo by John Kell under CC 2.0.

And the flames of hell, they seemed so high

When I could barely see over the pew

I was just a boy when they told me that lie

But lord, it felt so true.And that’s a hell of a thing to do to a kid

Just to teach him right from wrong

You can burn in hell the rest of your days

Or you can choose to sing along.— "Sing Along," from Ellis' 2014 album "Lights From the Chemical Plant"

Mike Nichols

On this date in 1931, Mike Nichols (né Igor Mikhail Peschkowsky), future luminary of stage and screen as an actor, director, producer and writer, was born in Berlin. His Jewish physician father, Pavel Nicholaiyevitch Peschkowsky, fled Russia to escape the Bolsheviks and then left Germany in 1938 to escape the Nazis, anglicizing his name to Paul Nichols in New York City.

Nichols and his younger brother were 7 and 3 when they boarded a ship to New York several months later, but their mother was left behind while convalescing from life-threatening deep vein thrombosis. Her father was a socialist intellectual and radical agitator who “was interested in religion as a field of research but had no use for it in his home, nor did his wife,” according to Mark Harris, author of Mike Nichols: A Life (2021). Harris’ husband is playwright Tony Kushner.

Nichols at age 4 had an allergic reaction to whooping cough vaccine, which made him bald and unable to grow hair ever again. At his segregated Jewish school, he would try to hide it under a cap, and for the rest of his life he remained sensitive about it and having to wear a wig and false eyebrows. Nor did this emotional adult have lashes to slow his tears.

He met Elaine May while attending the University of Chicago and playing the lead in Strindberg’s play “Miss Julie.” It was the start of their collaboration as the improv act Nichols and May that led to national fame and a fair amount of fortune via television appearances. They were soulmates intellectually and professionally for much of the rest of his life but were romantic partners only briefly. They won a Grammy for Best Comedy Album in 1962.

It’s daunting to try to recap Nichols’ accomplishments in this limited space. He directed or produced over 25 Broadway plays and consulted on numerous others. Start with 1963, when he was chosen to direct Neil Simon’s “Barefoot In The Park. It ran on Broadway for 1,530 performances and earned him a Tony Award, the first of nine he would win as producer or director. Directing Simon’s “The Odd Couple,” starring Art Carney and Walter Matthau, brought him another in 1965. Others followed for “Plaza Suite,” “The Prisoner of Second Avenue,” “Annie,” “The Real Thing,” “Monty Python’s Spamalot” and a 2012 revival (when he was 80) of “Death of a Salesman.”

On to Hollywood: Best Director Oscar for “The Graduate” (1967) and nominations for “Silkwood,” “Working Girl,” “The Remains of the Day” and “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” Primetime Emmys: “Wit” (2001) and Kushner’s “Angels in America” (2003).

His other movies: “Catch-22” (1970), “Carnal Knowledge” (1971), “The Day of the Dolphin” (1973), “The Fortune” (1975), “Gilda Live” (1980), “Silkwood” (1983), “Heartburn” (1986), “Biloxi Blues” (1986), “Working Girl” (1988), “Postcards from the Edge” (1990), “Regarding Henry” (1991), “Wolf” (1994), “The Birdcage” (1996), “Primary Colors” (1998), “What Planet Are You From?” (1998), “Closer” (2004) and finally, “Charlie Wilson’s War” (2007).

Nichols was married four times and had two daughters and a son. He married television journalist Diane Sawyer on Martha’s Vineyard in 1988 when he was 58 and she was 44. It was her first marriage. His truly was a lifestyle of the rich and famous, with frequent worldwide travel and expensive homes. At one point he owned and stabled 80 horses, mostly Arabians.

Growing up, “No one in my family would have known how to have a Jewish holiday,” Nichols said. His three children “were not raised in any faith.” Once when his son Max asked if they could celebrate Jewish holidays the next year, Nichols suggested they go to “Saturday Night Live” creator Lorne Michaels’ seder to start learning about that tradition, but Max soon dropped the celebration idea. (Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk about Being Jewish, by Abigail Pogrebin, 2005)

The last Broadway play he directed, the 2013 revival of Harold Pinter’s “Betrayal,” was panned by most critics. Nichols’ health was declining measurably, hastened by years of heavy smoking (including crack cocaine in the mid-’80s) and his gourmand proclivities. He died at age 83 of a heart attack at home a few hours after going out for dinner with Sawyer and his children. A small private service was held at a nearby funeral home. D. 2014.

PHOTO: Nichols at the premiere of “Charlie Wilson’s War” in 2007 at Universal Studios in Hollywood; photo by Tinseltown / Shutterstock.com

ABIGAIL POGREBIN: Does Nichols connect in any spiritual way to being Jewish or is it heritage that moved him?

NICHOLS: Certainly heritage. Religion? I would have to say, no. In an intellectual way, I’m glad that the Jewish religion doesn’t contain things that I find really difficult, like eating God. That’s not one of the things that I would want to do with God.— Ibid., Pogrebin, 2005. Catholic friends had explained to Nichols that transubstantiation (the communion wafer becoming the body of Christ) was literal, not a metaphor.