May 2

Catherine the Great

On this date in 1729, Catherine II, the rationalist Empress of Russia, was born as Sophie Augusta Friederika in the province of Pomerania in Prussia. The daughter of the prince of Anhalt-Serbst, she was groomed at 14 to be the future wife of Peter, the disreputable heir to the Russian throne. Sophie moved to Moscow to be educated for her position. Her name changed to Catherine when she was received into the Russian Orthodox Church and married in 1745. She and colleagues, allegedly including her lover Orlov, deposed Peter III in a popular coup d’etat in 1762, when she assumed the throne at age 33 as Catherine II.

Catherine admired and corresponded with French rationalists such as Voltaire and Diderot, launched reforms, transformed St. Petersburg, wrote stories, and was a patron of the arts who helped to pave the way for the great 19th-century flowering of art, music and literature in Russia. She had an outsized need for affection and adulation, bonding with a dozen known lovers, but the more salacious myths about her were likely started by her political enemies.

Along with diplomatic methods, she used the military to violently expand her empire’s borders. More positively, she reformed the judiciary and governmental administration. She founded Russia’s first government funded library and women’s school, promoted a national education system and wrote a progressive legal code known as the Nakaz which, although never implemented, served as a widely respected and visionary template for future governments even beyond her borders.

Catherine responded to peasant revolts and the French Revolution with increasing conservatism and remained a Deist until her death at age 67 of a stroke. (D. 1796)

“As Empress, Catherine endeavoured to enforce the enlightened humanitarian views of the great French Rationalists, with whom she was in complete sympathy. Her reforms, in regard to education, justice, sanitation, industry, etc., were of great value.”

— Joseph McCabe, "A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists"

Yoram Kaniuk

On this date in 1930, author and painter Yoram Kaniuk was born in Tel Aviv in the British Mandate of Palestine. His father was the first curator of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. His godfather, Hayyim Nahman Bialak, was a pioneer of modern Hebrew poetry and his grandfather taught Hebrew and wrote textbooks.

While Kaniuk was still a teen, he served in Israel’s 1948 War of Independence. While serving, he was wounded when an Englishman disguised in a kaffiyeh (headdress) shot him in the legs. This, along with other of Kanuik’s profound experiences, inspired the nearly 30 novels he produced. Some of Kaniuk’s best-known works are Hemo, King of Jerusalem (1948), Confessions of a Good Arab (1984) and His Daughter (1988). His writings focused on the war, the Holocaust and the prospects for peace between Israelis and Palestinians.

Kaniuk spoke out against religious extremism and in 2011 won a legal battle in the district court of Tel Aviv in which he successfully appealed to change the status of his official national identity from Jewish to no religion. He advocated for the freedom of the next generation to identify as Jewish by nationality rather than by religion.

In his final years he battled bone marrow cancer and became fascinated with death. His final novel, Between Life and Death, detailed the four months he spent in a coma near the end of his existence. Upon his death, Kaniuk donated his body to science to avoid ultra-Orthodox funeral rituals.

In 1958 while living in the U.S., Kaniuk married Miranda Baker, a Christian, and returned to Israel with her. They had two daughters, Aya and Naomi. He died of cancer at age 83. (D. 2013)

“[Israel] established a state out of religion rather than the nation we almost became. Along the way we did not stop in the hallway of civilization, and religion attached itself to us like a leech, because that is the only way it survives, and now it has come back and returned.”

— Kaniuk, quoted a month before he died, "Yoram Kaniuk’s last published words: ‘We messed it up." (The Times of Israel, June 9, 2013)

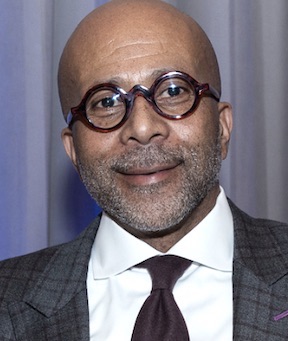

Anthony B. Pinn

On this date in 1964, humanist scholar Anthony Bernard Pinn was born to Raymond and Anne Pinn in Buffalo, N.Y. He grew up going to Baptist and African Methodist Episcopal (AME) churches and decided that he was going to be a minister. He preached his first sermon from the pulpit at age 12 and later transferred from public school to a Southern Baptist high school before enrolling at Columbia University, where he earned a B.A. He worked as an AME youth pastor in Brooklyn and Boston but started to believe that the church had no real answers to people’s problems. “I was moving from this kind of evangelical fundamentalist position to something more along the lines of the social gospel, but it still wasn’t getting it done.” (October 2014 speech at the Freedom From Religion Foundation’s national convention.)

Continuing his studies, he earned a master of divinity degree and a Ph.D. in philosophy from Harvard in 1994. His dissertation title was “ Wonder as I Wonder: An Examination of the Problem of Evil in African-American Religious Thought.” He had been questioning whether God existed and was having issues with theism more than religion. He asked himself, “Do the people matter, or is it the tradition that matters?” He relinquished his minister’s credentials, remaining interested in religion but seeing it as “a force that needed to be wrestled with and understood as a cultural development that shaped world events in some profound ways.” In his first book, Suffering and Evil in Black Theology (1995), Pinn discussed theodicy (why God permits evil) from an African-American perspective. How, he asked, can black theists, particularly black theologians, make sense of a perfect, benevolent God in light of African-American suffering?

After teaching at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, Suffolk University and Macalester College, he accepted an offer in 2003 from Rice University in Houston, becoming the first African-American to hold an endowed chair there as a professor of humanities and religion. Pinn is the founding director of the Center for Engaged Research and Collaborative Learning at Rice and director of the Institute for Humanist Studies in Washington. He’s the author, co-author or editor of more than 35 books, including the Fortress Introduction to Black Church History (with his mother, Anne H. Pinn, an AME minister, in 2001), The End of God-Talk: An African American Humanist Theology (2011), Writing God’s Obituary: How a Good Methodist Became a Better Atheist (2014), Humanism: Essays in Race, Religion, and Cultural Production (2015) and When Colorblindness Isn’t the Answer: Humanism and the Challenge of Race (2017).

His awards include the African-American Humanist Award from the Council for Secular Humanism (1999), Harvard University Humanist Association Humanist of the Year (2006) and Unitarian Universalist Humanist Association Humanist of the Year (2017). He was named a recipient in 2019 of FFRF’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award for speaking truth to power. Pinn’s research interests include humanism and hip hop culture. He married journalist Cheryl Johnson in 2000. They separated in 2005 and divorced in 2015.

PHOTO: Pinn receiving FFRF’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award; Ingrid Laas photo.

“For me the title is a way of capturing the decline and eventual death of a concept — God — that had been important to me for years. I wanted the title to reflect my transition from theism to nontheistic humanism through my push away from God — God being the central category of my religious youth.”

— Anthony Pinn, interview, Religion News Service, April 1, 2014, on his book "Writing God’s Obituary: How a Good Methodist Became a Better Atheist"

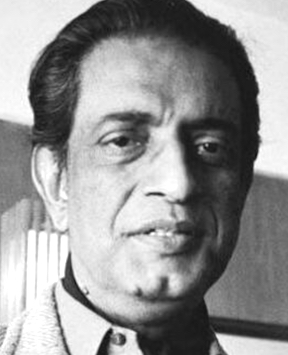

Satyajit Ray

On this date in 1921, legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray was born in Kolkata, India. His father, Sukumar Ray, was an eminent children’s writer and illustrator who died when he was 2. His mother raised him in the home of his paternal grandfather Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhary, also an accomplished writer.

After earning a degree in economics from Presidency College, Ray majored in fine art at the Visva-Bharati University, established by Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore. He then went on to work for a British advertising agency.

Ray had developed a deep interest in cinema by this time and helped establish the Calcutta Film Society. He assisted the iconic French director Jean Renoir when Renoir filmed “The River” in India in 1951. Ray decided to adapt a Bengali novel for his first film, “Pather Panchali” (“Song of the Little Road”).

This became the initial installment of the Apu trilogy, thought to be one of the finest achievements in the history of cinema. Ray went on to direct 36 movies, including 29 feature films, many of which are considered classics.

A humanist ethos pervaded his movies, which ranged from historical treatments and contemporary sociopolitical themes to interpersonal sagas and detective stories. His depiction of women was particularly noteworthy, with a number of his movies featuring strong female protagonists.

His work won awards at major film festivals, including Cannes, Venice and Berlin, and received admiration from directors such as Martin Scorsese (who led the campaign to get Ray an Oscar) and Wes Anderson (who used Ray’s music as the background score for “The Darjeeling Limited”). Ray’s Honorary Academy Award in 1992 “in recognition of his rare mastery of the art of motion pictures and of his profound humanitarian outlook” was flown into his Kolkata hospital room. He died 24 days later.

Ray’s movies often critique organized religion. “Devi” (“The Goddess”) portrays the negative ramifications of a young bride being worshipped as divine in 19th century rural Bengal. “Ganashatru” (“An Enemy of the People”), an adaptation of the classic Ibsen play, shows how a doctor is ostracized when he has the temerity to point out that the supposedly holy temple water is contaminated.

“Mahapurush” (“The Holy Man”) exposes godmen. (Godman is a term for a type of healer or spiritual leader with paranormal powers seen as a demigod-like figure by cult followers.) “Sadgati” (“Deliverance”) depicts the horrific consequences of the caste system. Ray was born to a reformist Hindu family but made clear his disdain for religion even if he sometimes hedged on his nonbelief.

“I was born into the Brahmo [a reformist Hindu sect] community, but I dislike such labels. Hinduism attracts me, with its coiled cultural layers, only as a rich source of contrastive situations and personalities. Well, I guess I’m an agnostic.” (“Satyajit Ray: Interviews,” ed. Bert Cardullo, 2007)

Ray suffered a heart attack in 1983 that severely limited his productivity in the remaining years of his life. A heavy smoker but nondrinker, he often worked into the wee hours of the morning. He died at age 70 due to his heart condition. (D. 1992)

PHOTO: Ray in New York in 1981; photo by Dinu Alam under CC 4.0.

INTERVIEWER: “Do you believe in God?”

RAY: “No. I don’t believe in religion either. At least not in organized religion. Nor have I felt the necessity for any personal religion.”— India Today, Feb. 15, 1983