March 1

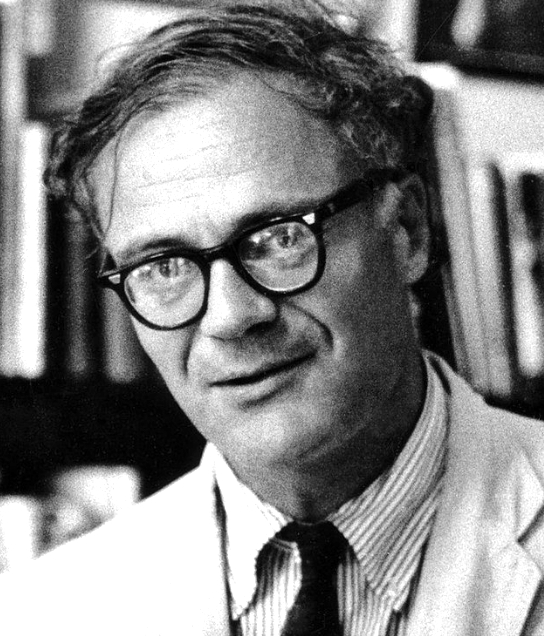

Robert Lowell

On this date in 1917, poet Robert Lowell, the great-grand nephew of James Russell Lowell, was born in Boston. At an early age, he knew he wanted to be a poet. As a 19-year-old, he wrote Ezra Pound a letter in which he confessed that Zeus and Achilles were “almost a religion” to him; how could the “insipid blackness of the Episcopalian Church” compete? (The New Yorker, March 20, 2017)

He attended Harvard for two years and eventually graduated from Kenyon College in 1940. He converted to Catholicism when he married novelist Jean Stafford. During World War II, he volunteered but was rejected due to poor vision. However, in 1943, he was drafted. Horrified by this time at the Allied bombing of civilians in Germany, Lowell became a conscientious objector, for which he was jailed as part of his sentence. He completed his first book, Land of Unlikeness, which was published as Lord Weary’s Castle in 1946 and received the 1947 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.

After divorcing (despite his conversion), Lowell married Elizabeth Hardwick, another writer, in 1949. The Mills of the Kavanaughs, Lowell’s next book, came out in 1951 to less acclaim. He suffered from manic depression in the 1950s, living much of the time in Europe. His career rebounded with Life Studies (1959), containing what one critic dubbed as “confessional” poetry.

Lowell became a Democratic activist in the 1960s, campaigning for Sen. Eugene McCarthy and against nuclear proliferation and the Vietnam War. His second marriage broke up and he married Caroline Blackwood in 1972. The Dolphin won the Pulitzer Prize in 1974. According to David Tribe in 100 Years of Freethought, Lowell became a freethinker. He translated the humanistic Prometheus Bound in 1969 (see quote below).

He died in 1977 at age 60 after suffering a heart attack in a cab in New York City on his way to see his ex-wife Elizabeth.

“[Prometheus to the chorus]: I have little faith now, but I still look for truth, some momentary crumbling foothold.”

— Lowell translation of Aeschylus' "Prometheus Bound" (1969)

Queen Caroline

On this date in 1683, Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach (née Wilhelmina Charlotte Caroline), who became queen of England, was born. Her father ruled the principality of Ansbach, one of the smallest Germanic states, before dying when Caroline was 3. An arranged marriage with the Austrian archduke was canceled when she refused to convert to Catholicism.

Marrying George Augustus, third in line to the British throne, in 1705, she became princess of Wales in 1714. After her husband was expelled from court in 1717 during a family dispute, Caroline became associated with Robert Walpole. Freethought historian Joseph McCabe reported that correspondence with Leibniz caused her to reject Christianity, and that her Richmond house “was more or less a Deistic center.” When George acceded to the throne as King George II in 1727, Caroline became queen consort. They had eight children, seven of whom survived to adulthood.

Horace Walpole, in his Reminiscences (1788), recorded that “when archbishop Potter was to administer the sacrament to her, she declined taking it” as she neared death. Caroline is the acknowledged patron of English landscape gardening, developing the Richmond and early Kew Gardens. Her gardening philosophy was “helping Nature, not losing it in art.” She died at age 54 in 1737 of a strangulated bowel after being in ill health for several years.

“The queen’s chief study was divinity; and she had rather weakened her faith than enlightened it. She was at least not orthodox; and her confidante lady Sundon, an absurd and pompous simpleton, swayed her countenance towards the less-believing clergy.”

— Horace Walpole, "Reminiscences" (1788)

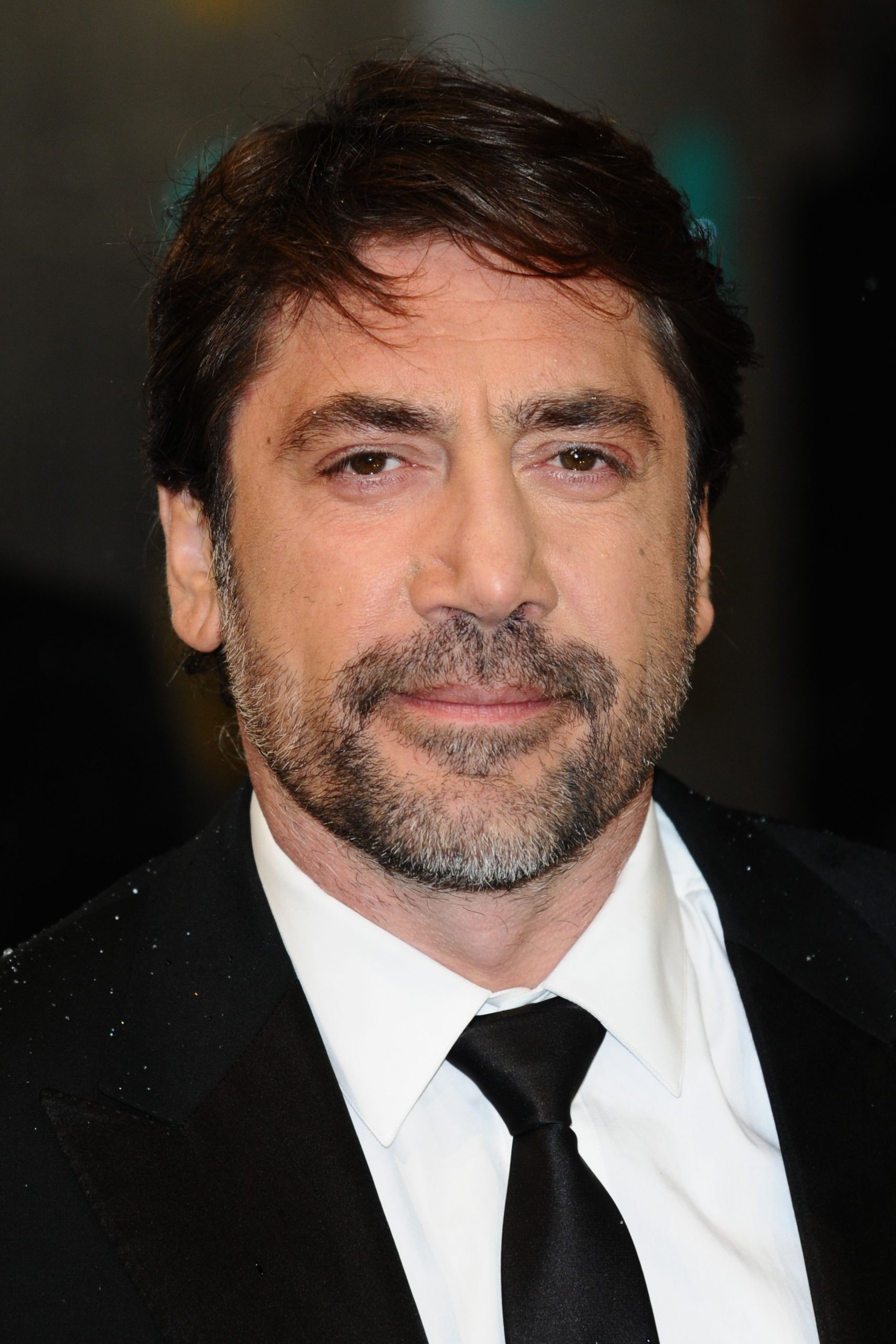

Javier Bardem

On this date in 1969, Javier Ángel Encinas Bardem was born in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria in the Canary Islands, Spain. Bardem grew up in a family of actors (except his father, who was a businessman). He began acting at age 6 in the Spanish television series “El Pícaro” (1974). As a teen he acted in television and played rugby for Spain’s national team. His breakthrough role was his Oscar-nominated portrayal of Cuban poet and novelist Reinaldo Arenas in “Before Night Falls” (2000).

Exceptional performances followed in “The Dancer Upstairs” (2002), directed by John Malkovich, “Collateral” (2004), “Goya’s Ghosts” (2006), also starring Natalie Portman, the Coen brothers’ “No Country for Old Men” (2007), “Love in the Time of Cholera” (2007), Woody Allen’s “Vicky Christina Barcelona” (2008), “Biutiful” (2010) and “Eat Pray Love” (2010). He won the 2008 Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his performance in “No Country for Old Men” and was nominated in 2011 in the Best Actor category for “Biutiful.”

In “Sons of the Clouds: The Last Colony” (2012), he demonstrated the suffering of the Sahrawi people in refugee camps. Other roles include 2017’s “Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales,” the horror film “Mother!” (2017) and with his spouse Penélope Cruz in “Everybody Knows” in 2018. He was cast as Stilgar in “Dune” (2021).

An article in The Independent (U.K.) refers to Bardem’s turning point with religion: “Now an atheist, he experienced the loss of his father when he was 25. ‘I wasn’t a very committed Catholic before, but when that happened it suddenly all felt so obvious: I now believe religion is our attempt to find an explanation; to feel more protected’ “ (“People watch me. I feel absurd,” Jan. 16, 2011).

After the 2005 legalization of same sex marriage in Spain, Bardem stated if he were a homosexual he would “get married tomorrow just to fuck with the church.” He and Cruz married in 2010 and have two children.

“I always say, ‘I don’t believe in God, I believe in Al Pacino’ — and that’s true.”

— Bardem, Time magazine, “10 questions for Javier Bardem" (Aug. 14, 2008)

Nuala O’Faolain

On this date in 1940, Irish journalist, memoirist and feminist Nuala O’Faolain (pronounced oh-FWAY-lawn) was born in Dublin, the second of nine children. Her unhappy childhood, lacking in love, inspired much of her later writing. Her father wrote a newspaper column for the Dublin Evening Press and, according to O’Faolain, spent many nights out in Dublin with little regard for his family. Her mother “sank into despair and alcoholism” as a result. (The New York Times, May 11, 2008.)

O’Faolain attended a Catholic convent school but was expelled for unruly behavior. She studied English at University College in Dublin and medieval English literature at the University of Hull in England. She earned a B.Phil. in English from Oxford in the 1960s. After her studies, she lectured in the English department at University College and then moved to London, where she established a broadcasting producer career with the BBC.

In 1977 she returned to Ireland to produce television programs, often with feminist content about Irish women. In 1986 she started writing a weekly column for the Irish Times. Her first memoir, Are You Somebody? (1996), won her international recognition. Following were successful novels, My Dream of You (2001) and The Story of Chicago May (2006). In 2003, Almost There, a sequel to her first memoir, was published.

O’Faolain had a 15-year relationship with the feminist journalist and playwright Nell McCafferty. She died in 2008 in Dublin from lung cancer at age 68. In an interview after her terminal diagnosis, O’Faolain stated she did not believe in an afterlife. (The Independent, interview with Marian Finucane, April 13, 2008). Her May 11 obituary in The Guardian stated, “The long and illustrious list of women who challenged the status quo — and changed Irish society in the process — had no more eloquent an exponent than Nuala O’Faolain.”

Nuala O’Faolain: And though I respect and adore the art that arises from the love of God and though nearly everybody I love and respect themselves believes in God, it is meaningless to me, really meaningless.

Marian Finucane: The reason I asked you is because it is a source of comfort for many people.

O’Faolain: Well, I wish them every comfort, but it is not even bothering me. I don’t even think about it. I have never believed in the Christian version of the individual creator.— O’Faolain interview, The Independent (April 13, 2008)

Scott Dikkers

On this date in 1965, humorist and entrepreneur Scott Dikkers was born in Minneapolis. While attending the University of Wisconsin-Madison, he started drawing a comic strip called Jim’s Journal that gained a small measure of local notoriety. He parlayed that into an unpaid spot on the staff of The Onion, a student humor newspaper started in 1988. The next year, he and Peter Haise bought the paper and started expanding it in terms of content and circulation beyond Madison.

The Onion’s small staff (described in one story as a “lone Jew surrounded by a collection of lapsed Lutherans and lapsed Catholics”) focused on making the mundane both irreverent and hilarious. A fair amount of that irreverence lands on religion’s shoulders. “Christians Growing Impatient for Third Coming of Christ” was the headline on one story. There are many, many others.

The Onion went online in 1996, which vastly increased its audience and renown. Dikkers co-wrote and edited The Onion’s first original book, Our Dumb Century, a best-selling spoof of recent history through Onion front pages, and Our Dumb World, a world atlas parody. In the mid-2000s, he spearheaded “The Onion News Network” web series, which won a Peabody Award in 2008 for its “ersatz news that has a worrisome ring of truth.”

That same year he addressed the Freedom From Religion Foundation’s national convention in Chicago. Dikkers was also included on Time magazine’s list of the Top 50 “Cyber Elite” along with Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, George Lucas and others. Headquarters moved to New York City in 2000-01 and to Chicago in 2012. The enterprise had been sold in 2003 to David Schafer. Dikkers remained as editor-in-chief from 2005–08 and is vice president for creative development as of this writing. Print publication ended in 2013.

He has written more than 20 humor books and developed the “Writing with The Onion” program at the Second City Training Center in Chicago. Described as reclusive and somewhat of a loner, he was, according to one story, married for a time, something that no one on the staff reportedly knew.

PHOTO by Brent Nicastro

“See, atheists and agnostics aren’t scary. Listen to their laughter! It’s a joyous sound, like the laughter of innocent children. You can trust us!

Furthermore, I want to say to the world, you need us. As I hope I’ve demonstrated here, atheists are fun. We’re fun to be with. We like playing make believe as much as the next guy, but we know the difference between fantasy and reality. And our crucial role in society is to remind everyone else of the cold, hard facts.”— Dikkers' speech to FFRF's national convention (Oct. 12, 2008)

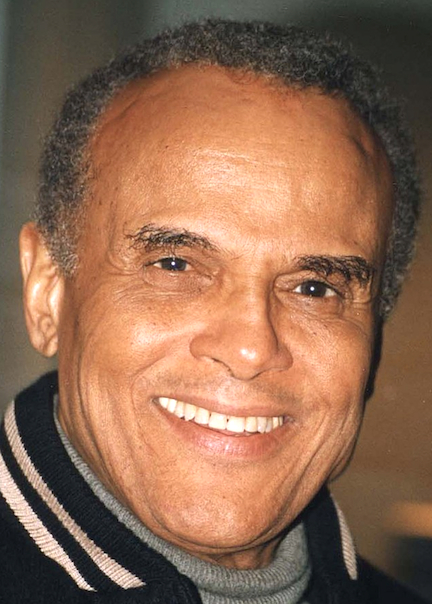

Harry Belafonte

On this date in 1927, singer Harry Belafonte (né Harold George Bellanfanti Jr.) was born in New York City in a Harlem hospital to Melvine “Millie” (Love) and Harold Bellanfanti Sr., respectively a maid/seamstress and a cook on a ship carrying bananas from Jamaica to the U.S.

His maternal grandparents were Scottish- and Afro-Jamaican, and his father was born on the island of Martinique to an Afro-Jamaican mother and a Dutch father of Jewish descent. That Belafonte’s parents were both undocumented likely led to the Anglicization of his surname. He attended Catholic services and parochial school. After Sunday Mass, his mother took him to the Apollo Theater to hear Cab Calloway or Count Basie or Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday or Ella Fitzgerald: “As suffocating and interminable as Mass seemed, I could endure it if I knew that a few short hours later I’d be in the real cathedral of spirituality.” (My Song: A Memoir, 2011)

“As my parents drifted apart, my mother grew more religious, which had direct implications for me,” Belafonte wrote. “My mother’s religion became everybody’s burden, especially my father’s.” His father’s fondness for alcohol didn’t help. (Ibid., My Song)

After a year in Jamaica living with his grandmother, he returned to New York, dropped out of high school and enlisted in the U.S. Navy, serving in 1944-45, loading ships bound for the Pacific from California. Just before he arrived in Port Chicago in Contra Costa County, a massive ammunition explosion killed 320 people, two-thirds of them Black sailors.

He started taking acting classes at the New School in the late 1940s alongside Marlon Brando, Tony Curtis, Walter Matthau, Bea Arthur and Sidney Poitier. Garnering roles in Broadway plays, he met Paul Robeson, one of his heroes. He had started singing in nightclubs to pay for acting classes, backed in his first appearance by the Charlie Parker combo. He signed a recording contract with RCA Victor in 1953.

Belafonte’s breakthrough album “Calypso” (1956) became the first million-selling LP by a single artist, spending 31 weeks at No. 1 on the Billboard charts. It included “Day-O” (The Banana Boat Song) and lines like “Lift six foot, seven foot, eight foot bunch/Daylight come and we want to go home.” Before long, he was making $50,000 a week with his Las Vegas show.

He had married Marguerite Byrd in 1948 and they had two daughters, Adrienne and Shari, but separated with Shari in utero. They divorced in 1957, the year that Belafonte and Joan Collins had an alleged affair during the filming of “Island in the Sun.” The marriage had been on shaky ground for some time and it stuck Belafonte as odd that Marguerite was resisting a divorce they both knew was inevitable. “One reason, for Marguerite, was her newfound Catholicism. … She knew how much I resented my Catholic education, and how fiercely I’d rejected the Church.” (Ibid., My Song)

Before the year was out, he married Julie Robinson, a former dancer with the Katherine Dunham Company who was of Jewish descent. They had a son, David, and in 1961 a daughter, Gina, the last of his children. They divorced in 2004 after 47 years of marriage. He married Pamela Frank, a photographer, in 2008. Neither wanted a religious wedding, so they married at Terrace in the Sky restaurant near Columbia University.

His artistry from the 1950s onward put him among fewer than two dozen EGOT recipients as of this writing in 2023 for winning Emmy, Grammy, Oscar and Tony awards for achievements in television, recording, film and Broadway theater. He recorded in genres from blues, folk, gospel, show tunes, jazz and American standards. He recorded two live albums at Carnegie Hall, performed at President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 inaugural and included harmonica player Bob Dylan on his 1962 LP “Midnight Special.”

He became friends with Martin Luther King Jr. and was deeply involved in the struggle for Black civil rights in a dangerous time. “For Martin the tenets of nonviolence aligned with his deep religious faith — and that I would struggle with, for unlike Martin, I questioned the honesty of the church and the existence of God. We’d talk a lot about that.” (Ibid., My Song) It was a time for strange bedfellows, as exemplified by Belafonte and actor Charlton Heston standing side by side at King’s massive march in 1963 on Washington, D.C.

Though he frequented churches during this period and later, it wasn’t about religion. “He’s not a believer, never was,” wrote author Jeff Sharlet, who interviewed Belafonte at age 84. “For him it’s political. He can’t forgive the church the slave catechism taught by traders of the flesh. … Every spiritual he sang on TV or in a concert hall was a message about this world, not the next. (Undertow: Scenes From a Slow Civil War, 2023)

The title track of his 1977 album “Turn the World Around” won plaudits after it was featured on “The Muppet Show” in 1979. He had discovered the song in the African nation of Guinea and the album was only released overseas. (“Water make the river/River wash the mountain/Fire make the sunlight/Turn the world around.”) He performed it at Jim Henson’s 1990 memorial, and in 2005 it was included in the official hymnal supplement of the Unitarian Universalist Association’s “Singing the Journey.”

He always credited his mother as a primary inspiration for his activism, with her words during his youth: “Don’t ever let injustice go by unchallenged.” (National Catholic Reporter, April 27, 2023) He died at age 96 from congestive heart failure at home in Manhattan, N.Y. (D. 2023)

PHOTO: At Meyerhoff Symphony Hall in Baltimore in 1996; © copyright John Mathew Smith under CC 2.0.

“To me, faith as practiced all around me was blindly tied to religion, and religion was preachers in Harlem and Jamaica passing the hat for Jesus and driving off in fancy cars. It was nuns invoking the Christian spirit and rapping my knuckles with sticks. It was priests blessing Italian troops on the newsreels, sending them off to slaughter defenseless Ethiopians. I failed to see any good in the hypocrisy of that.”

— "My Song: A Memoir," with Michael Shnayerson (2011)